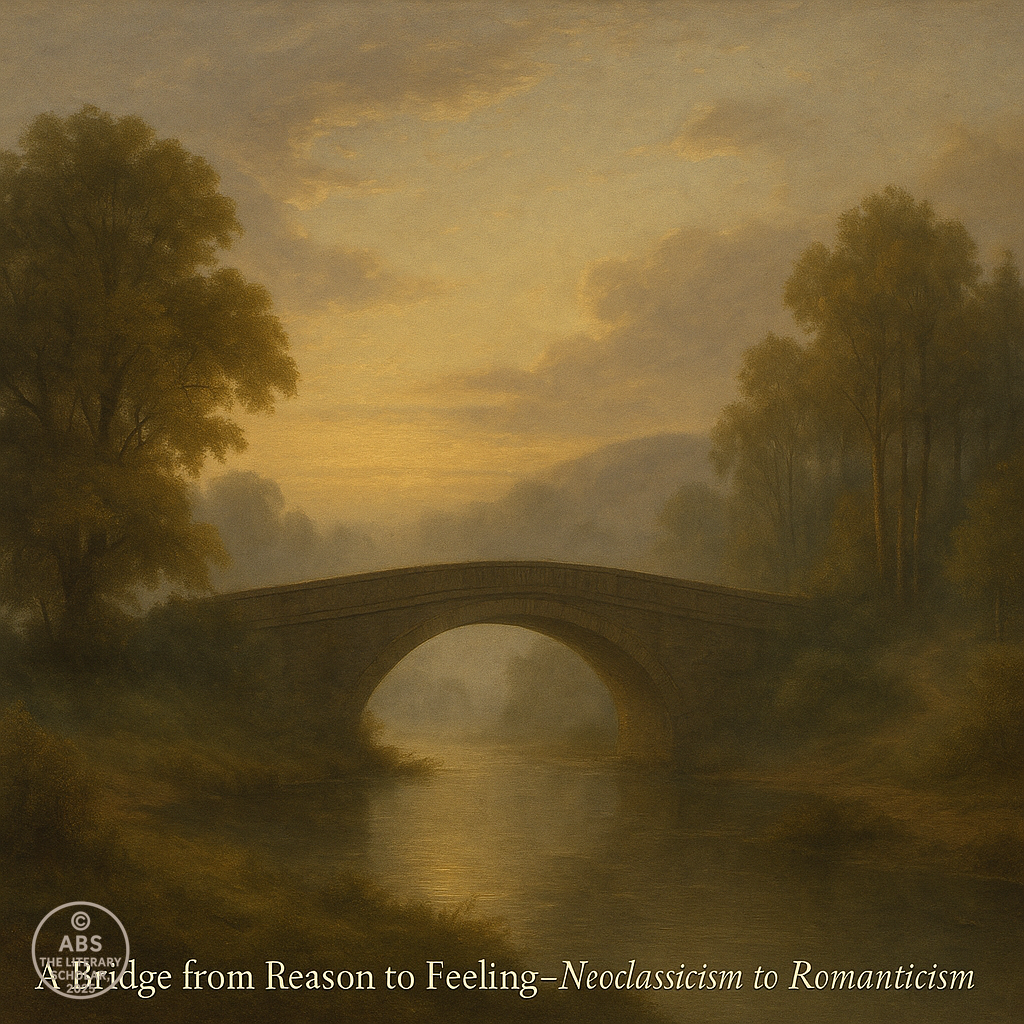

A slow turning of the poetic tide from reason to resonance, from order to emotion, from the classical to the human heart.

From The Professor's Desk

There are times in the history of literature when no trumpet is sounded, no manifesto declared, yet a quiet revolution begins to stir. The late 18th century was such a time — a period where poets, weary of the grand architecture of Neoclassicism, began to listen once again to the whisper of the leaves, the pulse of personal emotion, and the undercurrents of the natural world.

The earlier century had celebrated Reason, Form, and Wit. Pope had taught that to err was human, to forgive divine — but poetry itself had become a formal game, a rhetorical exercise often distanced from raw human feeling. Yet beneath this polished surface, the world was changing. The landscape of England, the philosophical winds of Europe, and the inner restlessness of the poetic mind were conspiring to forge a new voice.

It was not a sudden break. No clear line divides the “Augustans” from the “Romantics.” Between them lies this subtle, profound Transition Era — a space where poetry began to reclaim the soul, where Nature was not a decorative backdrop but a living presence, and where the poet’s role shifted from moralist to seer of the inner and outer worlds.

In this era, sometimes called “Pre-Romantic,” one can hear the first tremors of what Wordsworth would later call the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings. But here, in these decades before Lyrical Ballads (1798), the language of poetry was already being remade — less heroic couplet, more elegiac line; less rule-bound imitation, more intuitive song.

This is the story of those voices — Thomson, Gray, Collins, Cowper, Burns, Blake — who prepared the poetic soil for the coming Romantic harvest.

The Neoclassical Hangover — When Reason Grew Cold

The 18th century had begun with a triumphant faith in human reason. The great Age of Enlightenment had convinced poets and philosophers alike that order, clarity, symmetry, and balance were the ideals to which art must aspire. Alexander Pope’s heroic couplets clicked like clockwork; Samuel Johnson’s moral essays breathed the grandeur of Rome; and the Augustan ideal — that art must instruct and delight — reigned supreme.

But ideals, when too long enshrined, can grow brittle. By the mid-1700s, the Augustan mode had begun to creak under its own perfection. The very qualities that once seemed noble — restraint, polish, reason — were now beginning to feel sterile. Life, after all, is not lived in couplets. And the human heart does not beat to the measure of iambic pentameter alone.

Society itself was changing. The industrial stirrings of England were beginning to alter both the landscape and the imagination. Nature, once treated in poetry as a formal garden — symmetrical, controlled, ornamental — was reasserting its wildness and its mood. Meanwhile, philosophy too was moving beyond Cartesian clarity; the sublime, as theorized by Edmund Burke, began to fascinate the poetic mind: that which overwhelms reason, that which inspires awe, terror, beauty beyond calculation.

It was in this atmosphere that some poets began to chafe at the inherited forms of their craft. They respected the tradition, but they sensed that new feelings demanded new language. Where was the room in the heroic couplet for solitude? For the humble life of the ploughman? For the mysterious hush of twilight or the unspoken sorrow of the grave?

Thus arose a generation of poets whose works bear the marks of this tension. They stood between two worlds — the inherited Neoclassical world of form and the emerging Romantic world of feeling. Their verse often wears the old garments but carries a new music beneath.

They are not yet fully Romantic — not yet storming the heavens with Byronic defiance, nor wandering the lakes with Wordsworthian reverie. Yet they began to sing, softly at first, of Nature’s moods, of personal loss, of mystical visions, of the quiet dignity of the common life. And in doing so, they cracked the marble mask of Augustan art, letting in the first breath of the Romantic wind.

The New Currents — The Call of Nature and Feeling

As the Neoclassical grip loosened, new poetic impulses began to flow across the literary landscape — not as a violent overthrow, but as a gradual seepage of feeling, mood, and sensibility.

It is tempting to think of the Pre-Romantic period as simply a time when Nature became fashionable. But this is too shallow a reading. What was happening was subtler, deeper. Nature was ceasing to be a symbol of human order — no longer the geometrical garden in Pope’s verse or the obedient backdrop for human dramas. Instead, it began to be felt as an independent force, with moods, rhythms, and meanings of its own.

Poets were beginning to listen to the land, not merely describe it. The rustle of leaves, the changing seasons, the call of the nightingale, the darkness of a storm — these were no longer decorative touches. They became bearers of feeling, symbols of states of mind, and emblems of the human condition itself.

Parallel to this shift was a growing awareness of emotion as the proper subject of poetry. The Augustan ideal had valued wit and decorum; poetry was meant to display reason’s control over passion. But now, poets were turning inward. They began to trust the private emotion, the spontaneous mood, the solitary reflection.

This was partly the result of philosophical shifts. Thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau were beginning to argue that civilization corrupts, while Nature heals. The individual’s inner voice was to be valued over social convention. “Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains,” wrote Rousseau — a sentiment that resonated with poets seeking to free verse from its Augustan chains.

And it was also influenced by the emerging aesthetic of the Sublime — that which exceeds the grasp of reason. Edmund Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) had a profound effect. Poets began to explore the emotional power of vast landscapes, ruins, storms, night, and the infinite. These were no longer mere settings; they were metaphors for the depths of human experience.

In this ferment of new feeling, two themes came to dominate:

The Call of Nature: not merely as scenery, but as companion, teacher, and mirror of the soul.

The Value of Feeling: emotion not as a weakness to be tamed, but as the source of authentic poetic expression.

It is in this context that we must understand the poets of this transitional age. They were not revolutionaries; they were seekers. They inherited the discipline of form from their predecessors, but they longed to speak in a more natural, feeling voice. Their best poems tremble with this tension — between the old and the new, between decorum and depth, between reason and the heart.

In their lines, we hear the first true voice of the Romantic spirit — not yet shouted from the mountaintop, but whispered in churchyards, in country lanes, in songs of innocence and experience.

Next, we turn to the key figures who gave this emerging voice its first clear accents — the poets of transition, whose works prepared the way for the great Romantic outpouring.

Key Figures of the Transition

The Pre-Romantic era is not an era of manifestos. Its poets did not proclaim themselves a school, nor did they reject the past wholesale. They stood with one foot in the Augustan tradition and one in the emerging Romantic sensibility.

Each brought to English poetry a distinct voice: one celebrated Nature’s unfolding seasons, another sang the quiet sorrows of the human lot, another evoked mystical visions, still another wrote in the simple language of the folk.

Together, they prepared the poetic ear to hear again what had been muffled for so long — the voice of the heart, the echoes of Nature, and the mystery of experience.

James Thomson (1700–1748) — The Poet of The Seasons

When we speak of the return of Nature to English poetry, we must begin with James Thomson, whose great poetic cycle The Seasons (1726–1730) sounded an early call toward the landscape as living presence.

Before Thomson, Nature had largely served as ornament in poetry — a classical trope, a frame for human action. But The Seasons invites us to see Nature as the main character itself: not an obedient servant to wit and decorum, but a force of endless change, beauty, and moral reflection.

Thomson wrote in blank verse — a choice that freed his poetry from the mechanical couplets of the age and allowed a more flowing, meditative style. Across the four long poems — Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter — he captured the moods of the earth with a new attentiveness.

“Come, gentle Spring, ethereal Mildness, come,

And from the bosom of yon dropping cloud,

While music wakes around, veil’d in a shower

Of shadowing roses, on our plains descend.”

In these lines, we already hear a poetic voice tuned to Nature’s breath — not merely describing but invoking its spirit.

But Thomson’s significance lies not only in his descriptive powers. What marked The Seasons as a transitional work was its philosophical undercurrent. Thomson saw Nature as a moral landscape — its cycles offering lessons on mutability, order, and the human condition.

Winter’s severity, for example, reminds us of the fragility of life; Spring’s renewal becomes a metaphor for hope and regeneration. Thus, beneath the surface of pastoral beauty lies a deeper meditative current — one that would later flow fully into Romantic poetry.

Moreover, Thomson’s portrayal of Nature was distinctly British, not classically idealized. He celebrated the actual English landscape: its mists, its rugged hills, its temperamental weather. In this, he planted a seed that would later bloom in the Lakeland poetry of Wordsworth and Coleridge.

In sum, James Thomson stands at the dawn of the Transition era. His verse taught poets to regard the natural world as more than setting — as meaning, as mood, as mirror of the human soul. Without The Seasons, the path toward Romantic Nature poetry would have been far less sure.

Thomas Gray (1716–1771) — The Melancholy of The Churchyard and the Shadow Over Eton

In the long twilight of the Neoclassical age, Thomas Gray emerged as a poet whose voice seemed already half-turned toward the emotional depths of the coming Romantic era.

Though a scholar of immense learning and a man of deliberate craftsmanship — he published relatively little in his lifetime — Gray is today remembered for a handful of poems that have resonated across centuries: most of all, the famous Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, but also his haunting *Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College.

Together, these works reveal a mind preoccupied not with the rational glories of empire or the moral certainties of the Augustan world, but with loss, transience, the mute nobility of the humble, and the tragic arc of human life.

The Churchyard Elegy — A Poetry of the Unheard

When Gray published his Elegy in 1751, it struck a profound chord. In an era still dominated by the grand public themes of state, satire, and heroism, here was a poem that lingered in a country churchyard, among unnamed graves, contemplating not the achievements of the great, but the silent virtues of the poor.

“The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd winds slowly o’er the lea,

The ploughman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.”

From the very first quatrain, we are drawn into a world of quiet, elegiac meditation. The scene is humble: evening falls, the daily labors end, and the poet is left alone amid the forgotten dead.

What follows is a profound reflection on mortality and human worth. Gray mourns not the loss of kings or conquerors, but of “mute inglorious Miltons” — those of innate genius whose lives were constrained by poverty and circumstance:

“Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathom’d caves of ocean bear;

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.”

Such lines, with their emotional immediacy and universal poignancy, announced that English poetry had rediscovered the power of simple human feeling. Here was a voice capable of sympathy with the humble, a voice tuned not to satirical brilliance but to compassion and melancholy insight.

The Elegy also anticipates Romantic themes in its treatment of Nature as a setting for mood. The twilight, the swaying elms, the gloom of evening — these are not decorative; they shape and embody the poem’s meditative tone.

Moreover, in its quiet moral questioning, the Elegy breaks from the confident moral pronouncements of the age. It suggests, tenderly, that worth is not measured by fame or power, and that death is the great leveler before which all human pretensions fall away.

It is no accident that this poem became one of the most widely loved in the English language. In its understated way, it taught poets that genuine emotion — not rhetorical flourish — was the deepest wellspring of verse.

Eton College — Childhood Shadowed by Fate

Another of Gray’s transitional masterpieces is his Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College (1747). On the surface, it is a nostalgic poem, composed when the poet revisited Eton and gazed upon the schoolboys at play, unaware of the future that awaited them.

Yet beneath the apparent charm lies a meditation on the brevity of innocence and the inexorable march of suffering and fate:

“Ah, happy hills, ah, pleasing shade,

Ah, fields belov’d in vain,

Where once my careless childhood stray’d,

A stranger yet to pain!”

This is the voice of a man who has seen the shadows that life will cast, and who watches the young with a bittersweet pity. The schoolboys are still in their golden hour — but already the poet imagines “the frown of Fate” that will pursue them:

“Yet ah! why should they know their fate,

Since sorrow never comes too late,

And happiness too swiftly flies?”

Here again, Gray anticipates Romantic themes:

The value of childhood innocence

The tragic knowledge of experience

The tension between the bliss of unknowing and the inevitable awakening to life’s trials

Indeed, one can hear an early echo of Wordsworth’s later reflections on childhood in these lines. The ode foreshadows that Romantic fascination with the psychological passage from innocence to experience — a theme that would later animate Blake, Wordsworth, and Coleridge.

Gray’s Lasting Place in the Transition

Though Gray wrote relatively few poems, his significance to the Pre-Romantic transition is immense. In both Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard and Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College, he demonstrated that poetry could move beyond public wit and toward private emotion.

He trusted the solitary mood; he allowed melancholy and compassion to fill his lines; he turned from the city to the countryside, from the famous to the forgotten.

Moreover, Gray’s high craftsmanship — his careful, musical phrasing, his mastery of tone — showed that poetry could be profoundly moving without rhetorical bombast.

If the heroic couplet was the emblem of the Augustan age, Gray’s elegiac quatrains and reflective odes pointed toward a new poetic language: one capable of embracing loss, mystery, the beauty of the ordinary, and the silent dignity of the unseen life.

In this, he prepared the way for what would soon follow: a poetry of feeling, of Nature, and of the solitary heart.

William Collins (1721–1759) — Odes of Emotion and Immediacy

William Collins belongs to that small but luminous group of transitional poets who helped turn English verse toward the expressive intensity of Romanticism. His surviving body of work is slender — fewer than a dozen major poems — but it includes some of the most influential odes of the mid-18th century.

What marks Collins as a Pre-Romantic is not merely his subject matter, but his emotional immediacy, his fascination with mood, music, and the unseen forces that shape the human soul. In a poetic landscape still dominated by wit and formal argument, Collins dared to speak in a voice that was lyrical, personal, and at times almost visionary.

Odes of the Heart

His most celebrated volume, Odes on Several Descriptive and Allegoric Subjects (1746), was a bold experiment for its time. While much 18th-century poetry prized clarity of thought and reason, Collins’s odes shimmer with atmosphere, emotional suggestion, and symbolic richness.

Perhaps the finest example is his haunting Ode to Evening — a poem that quietly announces a new poetic sensibility:

“If aught of oaten stop, or pastoral song,

May hope, chaste Eve, to soothe thy modest ear,

Like thy own solemn springs,

Thy springs, and dying gales;”

The ode is suffused with a reverence for Nature’s moods — not the grandiose landscapes of classical epic, but the subtle, shifting atmosphere of twilight. The speaker addresses Evening as a living, quasi-divine presence, embodying the mystery and transience of time.

This is not poetry of moral argument or social satire; it is a poetry of felt experience, seeking to evoke rather than explain. The personification of abstract moods, the musicality of the phrasing, and the immersion in Nature’s sensory world all mark a clear departure from Neoclassical convention.

Emotional and Allegorical Vision

Another of Collins’s significant works is Ode on the Passions — a bold attempt to dramatize the emotions themselves. In this remarkable poem, Joy, Anger, Fear, Despair, Hope, and Pity are personified as characters in a kind of allegorical symphony.

“When Music, heavenly maid, was young,

While yet in early Greece she sung,

The Passions oft, to hear her shell,

Throng’d around her magic cell.”

Here Collins draws upon the ancient tradition of allegory, but what is striking is the dynamic emotional energy of the poem. Each Passion is described not as an abstract concept, but as a living force — moving, acting, performing.

This fascination with the drama of emotion would become central to Romantic poetry. One hears, in Collins’s ode, an early echo of the emotional immediacy that would later fill the pages of Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads or the visionary flights of Blake.

The Poetic Struggle

Collins’s life was marked by struggle and tragedy. He suffered from mental illness in his later years — a fact that has often been linked to the intense emotional sensitivity of his verse. Unlike the confident public poets of the Augustan tradition, Collins was a solitary, inwardly driven artist, whose poems often seem to emerge from the private recesses of feeling and imagination.

His poetry was not widely recognized in his lifetime, but later generations — especially the Romantics — saw in his work a precursor to their own ideals:

-

Nature as a living presence

-

Emotion as poetic truth

-

The power of mood and music in verse

-

The role of the solitary, visionary poet

Collins in the Transition

In assessing Collins’s place in the Pre-Romantic transition, one must recognize that he did not write political verse, nor did he seek to moralize the public. Instead, he wrote odes of inwardness — poems that sought to capture fleeting states of feeling, to give voice to the soul’s response to Nature and to life’s mysteries.

His language was often daringly musical; his imagery was deliberately suggestive rather than explanatory. In this, he helped to move English poetry away from the rational clarity of the Enlightenment and toward the symbolic, emotive, and visionary mode that would soon blossom in Romanticism.

If the Augustan poets gave us the Age of Reason, Collins gave us the first true notes of the Age of Sensibility.

William Cowper (1731–1800) — Plain Diction, Deep Feeling

Few poets in the English tradition embody the spirit of emotional honesty and plain speech as clearly as William Cowper. Though often classed with the Augustans by chronology, Cowper’s verse speaks a profoundly different language — one that points forward to the Romantic ethos of sincerity, natural expression, and personal feeling.

Cowper’s poetry marks an essential transition: it rejects the grandiosity and artificiality of heroic couplets, instead embracing blank verse and the unadorned rhythms of everyday speech. His subjects are likewise modest: Nature, domestic life, personal grief, and spiritual struggle. Yet within this simplicity lies a depth of feeling that anticipates the most heartfelt works of Wordsworth and Coleridge.

The Task — Nature and Reflection

Cowper’s major work, The Task (1785), is in many ways a landmark of Pre-Romantic sensibility. Written in blank verse at the urging of a friend (who had suggested a poem on “The Sofa”), the poem grew into a long, meditative exploration of Nature, society, and the inner life of the poet.

“God made the country, and man made the town.”

This line, often quoted, captures a central theme of Cowper’s poetry: a deep love of the rural world, combined with an implicit critique of urban corruption and artificiality.

In The Task, Cowper wanders the English countryside — not as a grand tourist, but as an observant, sensitive soul, attuned to the small beauties of Nature:

The changing seasons

The flight of birds

The flow of streams

The solitude of the woods

Such observations are rendered not in elevated diction, but in simple, transparent language — a deliberate rejection of the rhetorical flourishes of Neoclassical verse.

Cowper’s vision of Nature is not mythologized; it is lived. He writes of it with the intimacy of one who finds in Nature’s presence a source of solace, especially amid personal sorrow and mental anguish — both of which marked his own life.

The Poetry of Personal Feeling — A Mother’s Picture

Perhaps the most poignant testament to Cowper’s place in the Transition Era is his deeply moving poem On the Receipt of My Mother’s Picture Out of Norfolk (1790).

Cowper had lost his mother when he was just six years old. More than fifty years later, upon receiving her portrait, he composed this elegy of pure personal grief and longing — a poem remarkable for its emotional directness, its plain diction, and its refusal to veil feeling behind artifice:

“Oh that those lips had language! Life has passed

With me but roughly since I heard thee last.

Those lips are thine — thy own sweet smile I see,

The same that oft in childhood solaced me.”

In these lines, the conventions of the age fall away. We are given not the moralizing voice of the Augustan poet, but the raw voice of the bereaved son, speaking across decades of loss to a mother whose image has reawakened an entire world of memory.

This is not poetry of public display; it is private utterance. And in this very intimacy lies its Pre-Romantic power. The poem embodies the Romantic belief that authentic emotion, simply expressed, is a proper and noble subject for verse.

Indeed, the Romantics revered this poem — Wordsworth praised it for its “simple pathos,” and one can trace its spirit in many of the emotionally charged lyrics of the coming generation.

Faith, Doubt, and the Inner Struggle

Cowper’s poetry is also marked by a profound sense of spiritual struggle. A devout Christian, he nevertheless battled depression and religious doubt throughout his life. These inner conflicts surface in much of his verse, adding to its emotional complexity.

In poems such as Light Shining Out of Darkness (“God moves in a mysterious way”), Cowper grapples with the apparent contradictions of faith and suffering — another theme that would deeply resonate with the later Romantics.

Moreover, his treatment of religious experience is highly personal, not doctrinal — emphasizing the solitary journey of the soul rather than public piety. This inwardness, this willingness to chart the terrain of the private conscience, is another mark of his place in the Transition Era.

Cowper’s Lasting Contribution

In sum, William Cowper helped to prepare English poetry for the coming Romantic wave in several key ways:

By adopting plain language and blank verse to convey natural speech and thought

By elevating the humble and everyday as worthy poetic subjects

By writing with emotional honesty and personal feeling, particularly in My Mother’s Picture

By portraying Nature not as ornament, but as moral and spiritual companion

In Cowper’s work, the formal masks of the 18th century begin to fall. The poet’s voice grows more human, more vulnerable, more attuned to the truths of the heart and the life of the spirit.

Without Cowper, the path from Gray’s elegiac melancholy to Wordsworth’s lyrical balladry would have been far less certain. He is a quiet but essential figure in the evolution of English poetic feeling.

Robert Burns (1759–1796) — Folk Voice and Democratic Song

With Robert Burns, we enter a new and vital current in the Pre-Romantic stream — one that brings the poetic voice down from the high seats of learning and into the hands and hearts of the common people.

Where Gray and Collins wrote in the refined language of the educated elite, and Cowper in plain but cultivated speech, Burns boldly reclaimed the Scottish dialect and folk idiom as legitimate vehicles for poetry. In doing so, he democratized the poetic voice and infused English literature with a living, vernacular vitality that would deeply influence the Romantics.

The Ploughman Poet

Burns’s biography is itself a testament to this democratizing impulse. Born to a poor farming family in Ayrshire, Scotland, he worked as a ploughman even as he developed an astonishing poetic gift.

When his Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect appeared in 1786, it caused a sensation. Here was a poet whose verse spoke not the language of the court or the academy, but of the field, the tavern, the hearth. Yet within this humble speech lay extraordinary wit, lyrical grace, and deep humanity.

Burns’s embrace of the Scots tongue was not an antiquarian exercise; it was an assertion that the language of the people could convey the full range of human feeling — love, sorrow, joy, defiance — as powerfully as any classical idiom.

“O my Luve’s like a red, red rose,

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve’s like the melodie

That’s sweetly played in tune.”

Here is lyrical beauty without affectation, a song that speaks directly to the heart, without mediation by learned artifice.

Emotion, Humanity, and the Common Life

Burns’s poetry celebrates the dignity of common experience:

The love of a lass

The labor of the plough

The joys of friendship

The trials of poverty

The solidarity of the oppressed

In poems such as To a Mouse, Burns draws profound moral reflection from the simplest incident — the disturbance of a field mouse’s nest while ploughing:

“But Mousie, thou art no thy lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!”

Here is philosophy clothed in homely speech, conveying a truth as ancient as tragedy itself: the unpredictability of life and the kinship of all living creatures in suffering and hope.

Such poems resonated with a world in the midst of social and political change. The ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity were beginning to stir across Europe, and Burns’s verse gave these ideals a local, emotional grounding. He was the people’s poet, writing not about the folk from a distance, but as one of them, sharing their joys and burdens.

Radical Spirit and Universal Appeal

Burns’s work carries a radical undercurrent that would soon become central to the Romantic movement. In a world of entrenched class privilege, he asserted through his verse the universal worth of human feeling — irrespective of wealth, birth, or education.

“A man’s a man for a’ that.”

This famous refrain from his song Is There for Honest Poverty became an anthem for the dignity of the common man — a sentiment that would echo through Wordsworth’s portraits of rural life and Shelley’s political odes.

Moreover, Burns’s poetry is joyfully physical — it celebrates the body, sensuality, and the pleasures of life, in contrast to the stiff decorum of earlier verse. In this, too, he anticipated Romantic freedom of expression.

Burns and the Romantic Inheritance

Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Byron all admired Burns deeply. Wordsworth famously declared that the genius of Burns was “not in what he had to say, but in the way he said it” — a way that spoke directly to the heart in the language of the people.

Burns taught the next generation that:

Local dialects and folk idioms could be vessels of great poetry

The humble and everyday were valid poetic subjects

Emotion and sincerity mattered more than rhetorical polish

Poetry should speak to universal human experience, not merely the elite

In this sense, Robert Burns helped to break the final fetters of Augustan formality and opened the way for the full Romantic celebration of individual feeling and rustic life.

If James Thomson had restored Nature, and Gray had voiced melancholy, and Cowper had reclaimed plain speech, it was Burns who fully restored the pulse of popular feeling to English poetry.

Without him, the Romantic movement would have lacked one of its most democratic, vibrant, and authentic notes.

William Blake (1757–1827) — Visionary and Mystic

If the Pre-Romantic Era gave poetry back its emotion, its Nature, and its plain human voice, then in William Blake, it found something more: vision.

Here was a poet who not only turned from Reason to Imagination, but who sought to redefine poetry itself — as prophecy, as revelation, as a door to unseen worlds.

Blake is a figure difficult to classify. In many ways, he belongs fully to Romanticism; yet he began his poetic work well within the 18th century, shaped by the intellectual ferment and social upheavals of his time.

His most famous works — Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794) — belong unmistakably to the Transition Era in their language, themes, and emotional power.

Yet behind their apparent simplicity lies a vast visionary project: Blake sought to create a poetic universe in which the deepest forces of good and evil, of freedom and oppression, of innocence and corruption, could be laid bare.

Songs of Innocence — The Lost Garden

The poems of Songs of Innocence capture a vision of prelapsarian purity — a world seen through the eyes of the child, uncorrupted by institution, power, or social hierarchy.

Blake’s language here is deceptively simple — using the nursery rhyme and folk ballad forms to convey profound moral and spiritual truths.

“Little Lamb who made thee

Dost thou know who made thee?”

The direct address to the lamb, the childlike tone, the innocent questioning — all point to a world where divinity is immanent in Nature and where the human soul remains untainted by social injustice.

Blake was no sentimentalist, however. The very simplicity of Songs of Innocence is meant to highlight the fragility of innocence in a fallen world.

Already, shadows lurk at the edges: the child who is “lock’d up” in the chimney sweep poem, the ominous “green plain” in The Little Black Boy where racial inequality is mystically confronted.

Songs of Experience — The Broken Vision

In Songs of Experience, Blake confronts the realities of adult life — not merely the loss of innocence, but the systematic corruption of church, state, and commerce.

The contrast with Songs of Innocence is often brutal:

“Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;”

Gone is the gentle questioning of The Lamb; in its place stands a creature of fierce mystery — symbol of divine energy, creative destruction, and moral ambiguity.

Blake’s Songs of Experience are a radical critique of his time:

The industrial exploitation of children

The hypocrisy of religious institutions

The brutality of imperial power

The loss of visionary imagination in a mechanized age

Yet these poems remain songs — their lyrical beauty undiminished even as they express anger, grief, and spiritual yearning.

The Visionary Poet

Blake’s significance in the Transition Era lies partly in his formal innovations — the use of plain, rhythmic language to convey complex visionary truths.

He rejected the polished wit of the Augustans, instead forging a poetry that was:

Mystical yet accessible

Emotionally immediate

Morally urgent

In this, he anticipated many of the Romantic ideals:

Poetry as the voice of the prophet

The primacy of the imagination

The critique of industrial and social oppression

The reverence for childhood, Nature, and the inner life

But Blake went further: he conceived of poetry not merely as personal expression, but as a means to transform human consciousness. His illuminated books — combining text and image, word and vision — sought to awaken in readers a new way of seeing.

Blake and the Romantic Future

Wordsworth admired Blake’s simplicity, though he did not fully grasp his prophetic project.

Coleridge, more attuned to Blake’s mystical side, recognized in him a poetic seer — one who could speak from the visionary depths of the mind.

Later poets, from Yeats to Allen Ginsberg, would claim Blake as a forerunner of visionary modernism.

But for the Pre-Romantic Era, Blake represents the final flowering of its richest possibilities:

Personal emotion

Democratic language

Nature as a living presence

Childhood as spiritual ideal

Imagination as the true realm of freedom

In his work, the transition to Romanticism is no longer potential — it is already realized. Yet Blake remains unique, standing at the edge of the age, one foot in the 18th century, the other in the timeless realm of vision.

The Spirit of Transition — What Changed in Poetry

By the final decades of the 18th century, English poetry had undergone a transformation as subtle as it was profound. The change was not announced in prefaces or manifestos; it unfolded quietly in the lines of poets who, though rooted in the inheritance of Neoclassicism, found themselves drawn to new ways of seeing, speaking, and feeling.

If we seek to understand the nature of this Transition Era, we must look beyond dates and movements to the deeper currents of sensibility that altered the landscape of verse.

From Public Voice to Private Emotion

Perhaps the most striking change was a shift in the role of the poet. The great Augustan voices — Dryden, Pope, Johnson — had written largely for the public ear, addressing themes of state, morality, and universal reason.

But the Transition poets turned inward. They wrote of:

Private grief (Gray’s Elegy)

Childhood memory (Gray’s Eton Ode)

Maternal loss (Cowper’s Mother’s Picture)

Solitary reflections in Nature (Thomson’s Seasons)

The struggles of the common folk (Burns’s songs)

Poetry had begun to feel again — not by grand proclamation, but by giving voice to the intimate truths of human experience.

The poet was no longer the moralist or the wit, but the seer of the heart — one who could articulate the inarticulate sorrows and hopes of the private soul.

From Ornament to Nature as Presence

Nature, too, had changed. In Neoclassical verse, it had often served as backdrop or emblem — a source of polite imagery drawn from the classical tradition.

But in the Transition Era, Nature emerged as a living presence, with moods, meanings, and a voice of its own:

Thomson’s landscapes breathed seasonal rhythms.

Gray’s churchyard was alive with evening light and shadow.

Collins’s Ode to Evening evoked twilight as a spiritual companion.

Cowper’s countryside was a realm of solace and moral reflection.

Blake’s lamb and tiger symbolized the primal forces of creation.

In this shift, we see the birth of the Romantic reverence for Nature — not as ornament, but as teacher, mirror, and source of inspiration.

From Heroic Couplets to Living Speech

Form, too, was quietly revolutionized. The heroic couplet, which had dominated English verse for a century, now seemed increasingly inadequate to convey subtle feeling and the varied rhythms of life.

Blank verse allowed Thomson and Cowper to write in a more natural, meditative flow.

Quatrains gave Gray’s Elegy its elegiac music.

Folk meters and song forms enabled Burns to reach the heart of the common listener.

Nursery rhyme rhythms lent Blake’s Songs their haunting simplicity and universal resonance.

Through these shifts, poetry was recovering its connection to spoken language — a movement that would culminate in Wordsworth’s call for “language really used by men.”

From Classical Imitation to the Voice of the Self

Finally, the Transition poets began to reject mere imitation of classical models in favor of the authentic voice of the self.

Where Augustan verse often prized allusion, decorum, and intellectual control, the Transition poets privileged:

Spontaneous feeling

The moral dignity of the common life

The personal voice

The visionary imagination

In this, they anticipated the Romantic conviction that poetry should be “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings”, shaped by emotion recollected in tranquility.

Toward the Romantic Horizon

By the eve of 1798, when Wordsworth and Coleridge would publish their revolutionary Lyrical Ballads, the ground had been well prepared.

Without the Nature hymns of Thomson, the melancholy of Gray, the emotional immediacy of Collins, the plain-spoken honesty of Cowper, the democratic voice of Burns, and the visionary daring of Blake, the Romantic movement would have lacked its essential roots in feeling and freedom.

The Transition Era stands, then, as a bridge between two great epochs:

From the Age of Reason → to the Age of Imagination.

From the public poet → to the private voice.

From artifice → to authenticity.

From Nature as decoration → to Nature as revelation.

It is a story not of revolution, but of deepening — of the poetic heart remembering its own pulse.

And when the full Romantic wave would soon break upon English letters, it would carry with it the deep undercurrents first stirred in this remarkable, transitional age.

Yet beyond these central poets, other voices and myths hovered at the edges of this transitional age, stirring the air with new possibilities. Among them was the tragic figure of Thomas Chatterton, the “marvellous boy”, whose forged medieval verses under the name of Rowley wove a spell of romantic medievalism that would haunt the imaginations of Coleridge, Keats, and others. In the rugged north, James Macpherson’s Ossian — though largely a fabrication — cast its melancholy, sublime epics across Europe, its twilight landscapes and heroic lament deeply shaping the Romantic taste for the remote and the mystical. And in Edward Young’s Night Thoughts, the graveyard school of poetry found one of its most enduring voices, plumbing the depths of mortality, melancholy, and the solitary soul.

These figures, though often standing just outside the main current of Pre-Romantic verse, served to deepen the pool from which the full Romantic river would soon flow — enriching it with tragic legend, ancient song, and the darkness of the human heart awaiting its new dawn.

The Era’s Lasting Legacy

The poets of the Transition Era were not revolutionaries in the usual sense. They did not storm the citadels of literary tradition with manifestos and radical pronouncements. They wrote within the inherited forms of their age — odes, elegies, songs, blank verse meditations.

Yet through their poems, the very spirit of English poetry was being transformed.

Emotion returned to the center of verse — not as an ornament, but as its proper substance. Where wit and reason had once ruled, now grief, tenderness, longing, vision, and wonder reclaimed their place.

Nature, too, was restored to its full power. The decorative garden of the Augustans gave way to the living landscape of Thomson, Cowper, and Wordsworth to come. No longer a mere backdrop, Nature became a moral and spiritual presence, shaping the inner life of the poet and the reader alike.

Form and language grew more flexible, more attuned to the rhythms of speech and song. The heroic couplet lost its stranglehold; blank verse and lyrical quatrains rose in its place. The vernacular voice — through Burns — found its rightful dignity in the poetic tradition.

And the poet’s role itself evolved. No longer merely the satirist or the moralist, the poet became:

The seer of the unseen (Blake)

The mourner of forgotten lives (Gray)

The celebrant of the rural world (Cowper, Burns)

The voice of democratic feeling (Burns again)

The prophet of the imagination (Blake again)

Without these voices, the Romantic movement could not have taken the shape it did. They did not overthrow the past, but they deepened its channels, allowing the great flood of Romantic feeling and vision to pour forth in the generation that followed.

Their legacy endures in every line of verse that dares to speak from the heart, that finds in Nature not an object, but a presence, and that trusts in the imagination as a way of knowing the world.

The Transition Era thus remains one of the most quietly influential periods in English literary history — the age when poetry began to feel again, and in doing so, prepared to sing anew.

The Literary Professor closes the scroll, gaze lingering a moment upon the twilight of this era — that subtle hour when the sun of reason sank, and the stars of imagination began to rise. The lesson is plain: when poetry listens to the human heart, it always finds its truest voice.

Signed,

The Literary Professor

A custodian of the evolving spirit of verse

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance