How Pope, Swift, and their circle forged an empire of order, satire, and style.

From The Professor's Desk

The Restoration had crowned wit as king, but even the cleverest jest must give way to a deeper need for order and truth. As England moved into the early 18th century, the nation craved not just entertainment, but clarity, civic virtue, and a literature that could reflect the growing complexities of an expanding empire and a changing society.

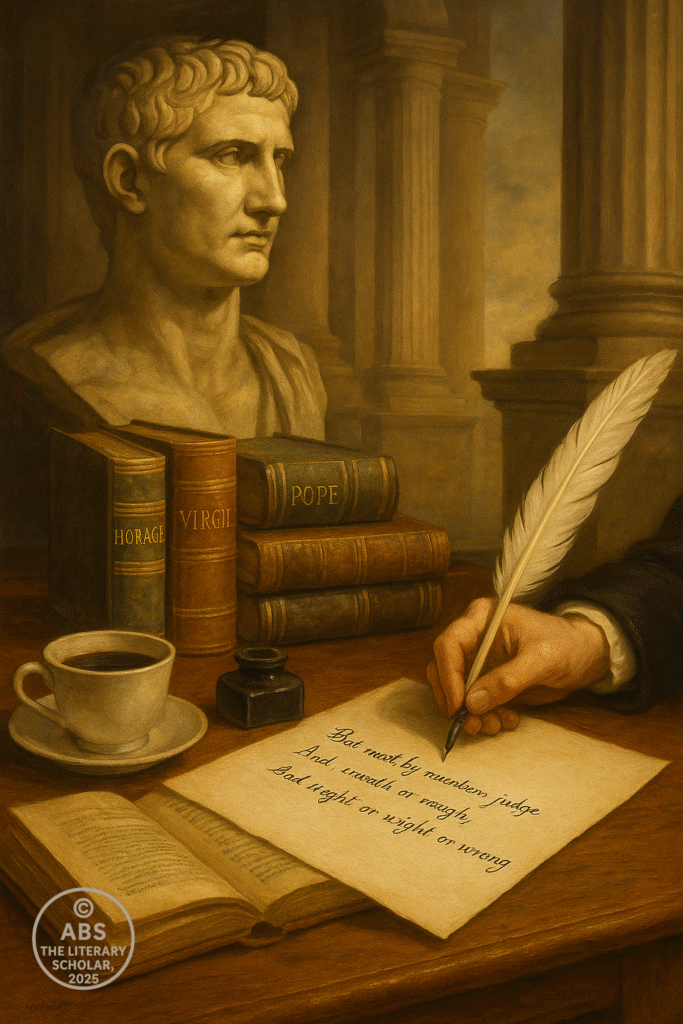

The coffeehouses of London had become parliaments of wit, where poets, essayists, and satirists debated not only style but substance. The heroic couplet, honed by Dryden, now reached its pinnacle under Alexander Pope. Satire became a moral instrument, wielded with elegance and precision.

This was the Augustan Age — so named because its writers saw themselves as heirs to the order and cultural refinement of ancient Rome under Augustus. Yet in their polished verse and razor-sharp prose, they also revealed the follies of their own age. Through Pope’s couplets, Swift’s prose, and Addison and Steele’s essays, English literature entered an era of disciplined brilliance, where reason ruled the rhyme.

A New Literary Empire: The Augustan Ideal

The Restoration had left English literature dressed in silk but burdened with cynicism. The stage glittered, the coffeehouses buzzed, but the soul of poetry seemed still searching for its purpose. As the 18th century dawned, a new literary mood emerged — one that sought not the laughter of the court, but the order of reason and the virtue of polished expression. This was the beginning of the Augustan Age.

Why Augustan? The writers of this period saw themselves as heirs to the cultural ideals of ancient Rome under Augustus — a time when Virgil, Horace, and Ovid had crafted a literature of civic pride, moral clarity, and elegant restraint. In an England seeking stability after decades of upheaval, such values held deep appeal.

The new middle class, empowered by commerce and literacy, demanded literature that addressed the concerns of reason, morality, and public life. The coffeehouses of London became the crucibles of this literary transformation. Here, amidst the scent of coffee and ink, poets, essayists, and critics debated not only the merits of verse but the very purpose of literature itself.

No longer content with the libertine excesses of Restoration Comedy or the closed games of courtly wit, the Augustans aspired to a national literature — one that could speak to the common reader without sacrificing intellectual elegance.

In this atmosphere, the values of the age crystallised around three ideals:

It was no accident that the heroic couplet, perfected by Dryden, now became the dominant poetic form. Its balanced rhythm and tight structure embodied the age’s passion for control and clarity. In the hands of Alexander Pope, the couplet would reach an unmatched level of refinement.

At the same time, prose rose to new heights. The periodical essays of Joseph Addison and Richard Steele brought moral discourse and social commentary into the everyday lives of readers. Through The Spectator and The Tatler, literature became a civilising force, shaping public taste and manners.

Jonathan Swift, meanwhile, wielded satire with a sharper blade. Where Pope’s couplets danced with elegant wit, Swift’s prose struck with brutal force. Gulliver’s Travels and A Modest Proposal would expose the follies and cruelties of human society with a clarity that left no refuge for hypocrisy.

Together, these writers forged a new literary empire — one not ruled by kings, but by reason and rhyme. They elevated English letters to a new level of civic engagement, proving that poetry and prose could both instruct and delight.

Yet this pursuit of order came with its own limitations. In striving for perfection of form, the Augustans risked losing the lyric spontaneity and emotional depth that had once animated English poetry. Their verse spoke to the mind more than the heart, to the elite more than the many.

As we turn now to Alexander Pope, we will see how one poet brought the ideals of the Augustan Age to shimmering perfection — crafting couplets as sharp as a blade and as polished as a mirror. In Pope’s hands, reason ruled the rhyme, but not without wit, grace, and occasional flashes of hard-won human insight.

Alexander Pope: The Master of the Couplets

If the Augustan Age had a single poetic voice, it was that of Alexander Pope — a man whose couplets defined the age and whose wit could both dazzle and destroy.

In Pope’s slender frame — he was afflicted with illness and deformity from a young age — there burned a fierce intellectual ambition. His physical limitations kept him from the public life of many of his contemporaries, but in the realm of letters, he reigned supreme.

“True wit is nature to advantage dressed,

What oft was thought, but ne’er so well expressed.”

— An Essay on Criticism

With lines such as these, Pope captured both the aesthetic ideal and the moral ambition of Augustan poetry. The poet’s task was not to invent new truths, but to express them with unmatched clarity and elegance.

Born in 1688, Pope grew up in an England where Catholics faced legal restrictions and social prejudice. Barred from public office and from formal university education, Pope educated himself voraciously. His early immersion in classical literature gave him both a reverence for form and an enduring love of moral clarity.

Pope’s mastery of the heroic couplet soon brought him public acclaim. His Pastorals and An Essay on Criticism revealed a poet of extraordinary technical skill — one who could balance form with substance, wit with wisdom.

But it was with The Rape of the Lock that Pope demonstrated the full potential of Augustan satire. This mock-epic — based on a trivial social quarrel — transformed a petty incident into a dazzling exploration of vanity, fashion, and social pretension.

“What dire offence from amorous causes springs,

What mighty contests rise from trivial things!”

In these opening lines, Pope set the tone: beneath the polished surface of polite society, human folly still ruled. His brilliance lay in exposing this folly with a smile, not a sneer — crafting verse that charmed even as it chastised.

Yet Pope was no mere court jester. His later works revealed a deeper moral seriousness. In Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot and Moral Essays, Pope turned his pen against the corruption of politics, the hypocrisy of the church, and the shallowness of fashionable society.

“Yes, I am proud; I must be proud to see

Men not afraid of God, afraid of me.”

— Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot

Here, Pope claimed his moral authority as a poet — one who, though excluded from political power, could still shape the moral conscience of the age.

Pope’s greatest ambition, however, was his translation of Homer. In rendering The Iliad and The Odyssey into English heroic couplets, Pope not only brought classical epic to new readers but demonstrated the heroic potential of his own art. His translations were both a literary triumph and a commercial success, securing his financial independence.

Yet beneath Pope’s polished verse lay a sharp edge. His literary rivalries were legendary, and his satirical pen spared few. In The Dunciad, Pope mocked the dullness of contemporary writers and the decline of literary standards:

“In fearless youth we tempt the heights of arts,

While from the bounded level of our parts.”

For all his wit, Pope was a deeply serious poet. He saw in the art of poetry not merely an avenue for fame, but a moral vocation — a means to uphold virtue, reason, and civility in an age increasingly corrupted by greed and folly.

As the embodiment of Augustan ideals, Pope’s influence was profound. His couplets set the standard for poetic form; his satire defined the moral tone of the age. In Pope, the Neoclassical pursuit of order, reason, and moral clarity found its purest voice.

Yet even as Pope perfected the style of his age, the seeds of change were stirring. The strict order of the couplet, the cool reason of satire, would soon be challenged by a new generation of poets seeking deeper feeling and greater freedom.

But before that Age of Sensibility could arise, one more giant would wield satire as a blade: Jonathan Swift, whose prose would strip away the illusions of society with a savagery that Pope’s couplets could only hint at.

Jonathan Swift: The Savage Satirist

If Alexander Pope was the jewelled blade of Augustan verse, then Jonathan Swift was its iron mace. Where Pope’s couplets sparkled with elegance and subtlety, Swift’s prose struck with blunt force, exposing the brutality, hypocrisy, and folly of human society with a clarity that left no room for illusion.

Born in 1667 in Dublin, Swift’s life was shaped by both political exile and personal frustration. Educated at Trinity College, Swift spent much of his career caught between two worlds — the rising literary circles of London and the turbulent politics of Ireland, where he would ultimately serve as Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

From this complex vantage point, Swift developed a literary style that was fiercely moral and deeply disenchanted. He believed in the potential of reason, but saw clearly how often it was perverted by self-interest and corruption. His prose became a weapon not of amusement, but of moral outrage.

In A Tale of a Tub, Swift mocked the absurdities of religious factions and intellectual pretension. His wit was relentless, refusing to spare even the most sacred targets. Yet it was with Gulliver’s Travels that Swift achieved his greatest and most enduring impact.

What appeared on the surface to be a children’s adventure was, in truth, a savage satire of politics, science, and human nature. In the land of the Lilliputians, Swift exposed the pettiness of court politics; in Brobdingnag, the vulgarity of European manners; in Laputa, the empty pretensions of abstract reason; and in the land of the Houyhnhnms, the moral bankruptcy of mankind itself.

“I cannot but conclude the bulk of your natives to be the most pernicious race of little odious vermin that nature ever suffered to crawl upon the surface of the earth.”

— Gulliver’s Travels

Such was Swift’s verdict on his own species — a condemnation rendered with such clarity and force that no reader could easily dismiss it.

In A Modest Proposal, Swift’s most infamous work, he turned his pen against the English exploitation of Ireland with a piece of deadpan irony so savage that it continues to shock modern readers. Proposing the sale of Irish infants as food for the rich, Swift forced his audience to confront the inhumanity of their own economic policies.

“I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance, that a young healthy child well nursed is, at a year old, a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food.”

Behind such horrifying irony lay a profound moral vision. Swift was not a misanthrope; he was a satirist driven by love for human potential and rage at its betrayal. His goal was not to amuse, but to awaken — to strip away the comforting lies that allowed injustice and cruelty to flourish.

Swift’s prose style matched his moral force. Clear, vigorous, and unadorned, it rejected the artificial polish of lesser writers. In an age of rhetorical elegance, Swift’s sentences marched with the weight of truth and the rhythm of anger.

Yet Swift was not without human tenderness. His private letters, especially those to Stella (Esther Johnson), reveal a man capable of deep feeling, though often trapped in a world that had taught him to mistrust it.

In the literary pantheon of the Augustan Age, Swift stands alone — a giant of prose, whose moral courage and stylistic brilliance continue to inspire and challenge. Where Pope refined the art of urbane satire, Swift reminded the age — and us — that some truths cannot be dressed in verse.

As we turn next to Addison and Steele, we will see how a different kind of literary force emerged — one that sought to shape the manners and morals of everyday life, bringing the ideals of reason and virtue to a wider public through the emerging art of the periodical essay.

The Prose of Reason: Addison and Steele

While Pope perfected the heroic couplet and Swift wielded satire like a sword, another revolution was quietly transforming English literature — this one led not from the stage or the poet’s study, but from the coffeehouses of London. Here, amidst the hum of conversation and the clink of porcelain cups, Joseph Addison and Richard Steele brought the ideals of reason, morality, and civic virtue into the daily lives of readers.

In doing so, they invented the modern periodical essay — a form that would profoundly shape public discourse and the role of literature itself.

The rise of the London coffeehouse in the late 17th and early 18th centuries had created new spaces for social and intellectual exchange. No longer confined to aristocratic salons or academic circles, literary debate now flourished among the educated middle classes — merchants, lawyers, clergymen, and even skilled artisans.

Sensing this opportunity, Addison and Steele launched The Tatler in 1709, followed by the more famous The Spectator in 1711. Their aim was not merely to inform or amuse, but to civilise — to promote a vision of polite, rational, and virtuous society.

“It was said of Socrates that he brought philosophy down from heaven to inhabit among men; and I shall be ambitious to have it said of me, that I have brought philosophy out of closets and libraries, schools and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea-tables and in coffee-houses.”

— The Spectator, No. 10

With this mission, Addison and Steele democratized literature. Through their essays, they brought moral reflection, philosophical insight, and literary taste into the everyday reading of thousands. The Spectator’s blend of graceful prose, gentle satire, and moral earnestness set a new standard for public discourse.

Unlike the biting irony of Swift or the brilliant couplets of Pope, the Spectator essays adopted a tone of urbanity and persuasion. They sought to reform manners without offending, to correct folly without cruelty.

“A man must be excessively stupid, as well as uncharitable, who believes there is no virtue but on his own side.”

— The Spectator, No. 257

Addison, in particular, brought to the essay a style of clarity, balance, and quiet charm. His writing exemplified the Augustan ideals of order and reason, avoiding both pedantry and vulgarity. Steele, more personal and engaging, infused the essays with warmth and anecdotal grace.

Together, they created a literary voice that was both instructive and accessible. The Spectator was read by men and women alike, in homes and coffeehouses, shaping the moral tone and literary taste of the middle class.

Importantly, the success of these periodicals signaled a shift in the literary landscape. No longer was literature the exclusive preserve of court poets or learned scholars. The reading public had expanded, and with it, the demand for writing that could educate as well as entertain.

In many ways, The Spectator anticipated the modern role of journalism and the essay. Its blend of commentary, social observation, and moral reflection laid the groundwork for the vibrant public sphere that would flourish in the centuries to come.

Moreover, Addison and Steele demonstrated that prose could be as refined and morally serious as verse. In their hands, the essay became a form of civic engagement, embodying the Augustan belief that reason should govern public life.

Yet even as their essays promoted politeness and virtue, they also revealed the limitations of the age. The Spectator’s vision of society was urbane, rational, and male — its ideals shaped largely by the values of the educated elite. The voices of the poor, the marginalized, and the emotionally restless remained largely unheard.

As we now prepare to close this part of the scroll, we must ask: What was the true legacy of the Augustan Age? It gave English literature an unmatched elegance of form and a profound commitment to reason and moral clarity. But it also sowed the seeds of a reaction — a longing for greater emotional depth, imagination, and freedom of expression.

In our final section, we will see how the Augustan ideal, though brilliant, could not hold forever. The Age of Sensibility was already stirring, and with it, a new literary revolution would soon begin.

The Augustan Legacy: Order and Its Limits

The Augustan Age had crowned reason and wit as the twin rulers of English letters. Under the disciplined hands of Pope, Swift, Addison, and Steele, literature had become an instrument of moral clarity, a mirror held up to society to reflect its follies and ideals.

Form was polished, prose was civilised, and poetry was ordered as never before. English literature had entered its age of elegant balance.

And yet — beneath this polished surface, one could already sense the stirrings of change.

The Augustan ideal had many strengths. It had taught English writers the value of clarity, precision, and restraint. It had elevated satire to a tool of civic responsibility. It had brought literature into the heart of public life, no longer confined to court or cloister.

But its limitations were equally clear. In exalting order, it risked sacrificing passion. In pursuing wit, it often neglected feeling. The strict symmetry of the heroic couplet could capture reason perfectly, but it struggled to convey the depths of human emotion.

“To err is human; to forgive, divine.”

— Alexander Pope

In this line, Pope encapsulated both the moral wisdom and the restraint of the age. Yet one can sense, too, a certain distance — a tone of moral observation rather than intimate confession.

Moreover, the Augustan vision of society was hierarchical and exclusive. It spoke largely to the urban elite, shaping the manners of those already privileged by education and class. The voices of the poor, the marginalised, and the emotionally turbulent remained largely outside its ordered frame.

By the mid-18th century, a new cultural and emotional climate was emerging. The Age of Sensibility — a term that would later define the transition — began to challenge the primacy of reason with a renewed emphasis on feeling, sympathy, and nature.

In poetry, this meant a turn away from the tight couplet toward more varied and expressive forms. In prose, it fostered a literature of empathy and introspection. The seeds of Romanticism were being planted in the soil of Augustan restraint.

Yet the Augustan legacy remains profound. It shaped a tradition of moral engagement, clarity of style, and public responsibility that would endure long after the heroic couplet had lost its throne. Its finest voices — Pope’s polished verse, Swift’s savage prose, Addison’s graceful essays — continue to command admiration, even in a world that has learned to prize emotion alongside reason.

As we prepare to enter the Age of Sensibility, we will see how the lyric heart of English literature, long subdued beneath the weight of order and wit, began once more to assert itself. The poets and prose writers of this new age would seek to reconcile feeling with form, nature with art, and in doing so, would open the way to the next great flowering of English letters.

The curtain falls, then, on the Augustan Age — an age of brilliance and boundaries, of moral purpose and aesthetic perfection. What comes next will speak in a different voice — one that listens as deeply to the heart as to the head.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance