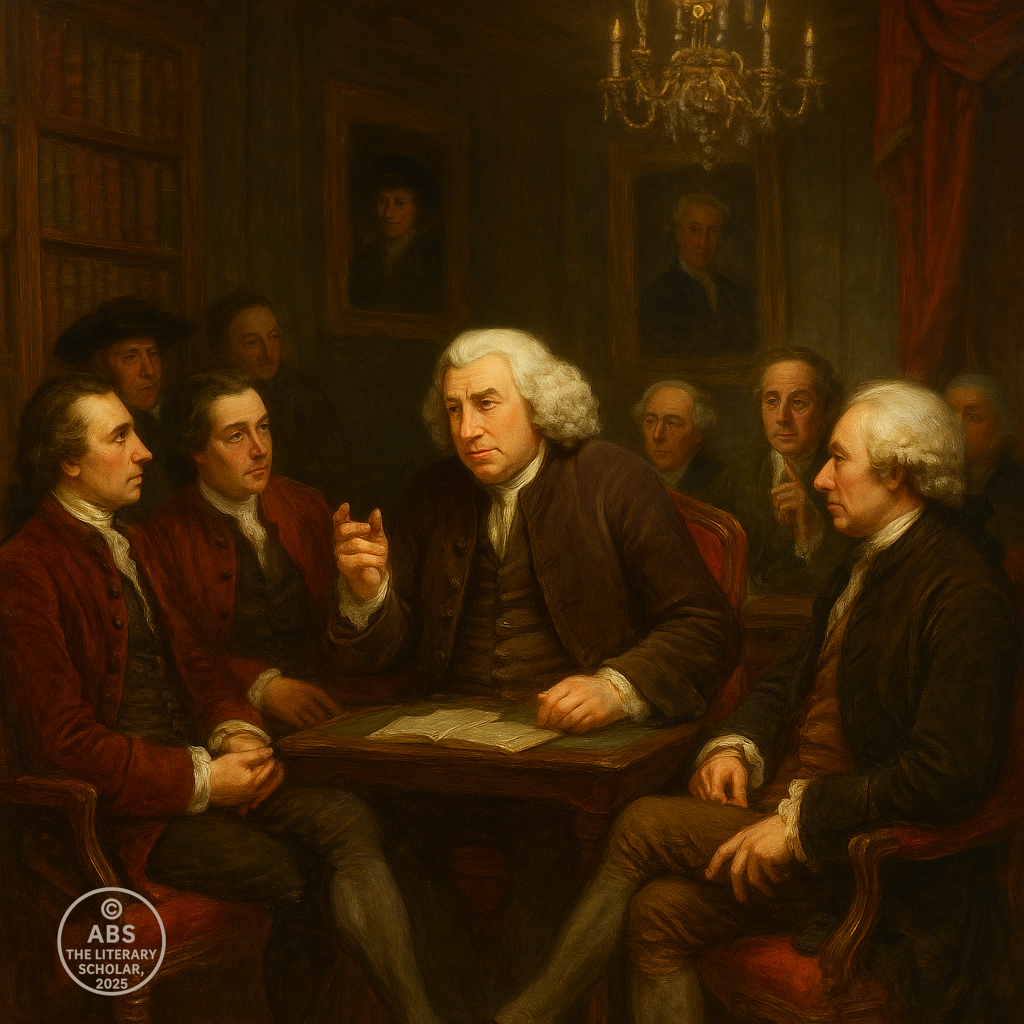

As the Age of Wit reached its twilight, Dr. Johnson and his circle preserved the elegance of reason and prose — even as the heart of poetry began to stir anew.

From The Professor's Desk

The Augustan Age had left English letters gleaming with polish, but the polish was beginning to wear thin. The triumph of order, clarity, and reason had defined the era of Pope and Swift, Addison and Steele. Yet as the decades passed, that brilliance began to feel remote — a style admired, but less and less inhabited. The heroic couplet no longer thrilled the ear; the satirical verse no longer stung with relevance. The public mood had changed, and so had the demands placed upon literature.

As the 18th century neared its middle decades, a different spirit began to rise — one that valued not the tight dance of wit, but the grave dignity of moral prose, the intellectual sweep of history, the serious engagement with life’s larger questions. Poetry yielded the throne to prose. The great literary monuments of this later Neoclassical period would be essays, histories, biographies, oratory — works designed to instruct, enlighten, and endure.

At the centre of this transformation stood one towering figure: Dr. Samuel Johnson. Lexicographer, essayist, critic, philosopher — Johnson became in many ways the living embodiment of the Neoclassical ideal in its final form. His mind was as disciplined as Pope’s verse, his prose as weighty as Dryden’s couplets, but his moral seriousness reached deeper. Where earlier wits had often laughed at the world’s follies, Johnson looked upon them with grave compassion and unflinching judgement.

Around him gathered a remarkable circle — writers, thinkers, and historians who shared this new vision of literature as a moral force. In the age of Johnson, literature spoke not merely to the mind, but to the conscience of a nation.

Yet the Neoclassical spirit itself was beginning to strain. The very virtues of order and reason were becoming limitations in a world that hungered increasingly for emotion, nature, and imaginative freedom. Johnson, though he stood at the height of his literary fame, recognised that he was also standing at the end of an era.

This is the story of that last great flowering of Neoclassicism — an age of prose kings, moral critics, and towering intellects. As we now open the scroll on the Age of Johnson, we will witness both the dignity of Neoclassicism’s final triumph and the shadows of its coming decline.

The Twilight of the Augustan Ideal

The death of Alexander Pope in 1744 marked more than the passing of a great poet — it signalled the end of the age when verse had ruled the literary world. The heroic couplet, so long the vehicle of moral satire and public wisdom, began to sound hollow in an England that was changing rapidly. Commerce, empire, and the growing influence of the middle classes transformed the nation’s intellectual landscape.

By the mid-18th century, London had become a city of new readers — merchants, professionals, gentlemen of leisure — who sought not the aristocratic wit of the past, but writing that could speak to their own moral concerns and intellectual curiosities. The periodical essay remained popular, but the great new works of the time were emerging in prose.

History, biography, criticism, and moral philosophy now commanded attention. The public wanted works that instructed the mind and shaped character, not merely entertained. Prose had taken the throne, and poetry, though still written, was no longer the chief voice of the nation’s culture.

This shift did not mean a rejection of Neoclassicism, but a transformation of it. The core values of the movement — clarity, balance, decorum, moral purpose — remained. But they now found their highest expression in the majestic rhythms of prose rather than the tight rhymes of verse.

Nowhere was this clearer than in the work of Dr. Samuel Johnson. As Pope had been the voice of Neoclassical poetry, Johnson would become the great voice of Neoclassical prose — a writer whose moral gravity and stylistic power would define an entire generation of English letters.

But Johnson did not emerge in a vacuum. He rose at a moment when English literary life was evolving — when readers hungered for serious engagement with history, ethics, and the human condition. It was an age that revered the past but also sensed the need to speak to a broader, more democratic audience.

In this twilight of the Augustan ideal, the centre of literary gravity shifted. No longer the poet’s couplet, but the critic’s judgement, the historian’s voice, the biographer’s portrait, would shape the intellectual life of England.

As we turn now to Dr. Johnson himself, we will see how one man, through sheer moral force and literary mastery, preserved the dignity of the Neoclassical tradition even as the winds of change began to stir.

Dr. Samuel Johnson: The Last Great Classicist

When literary England seemed poised to drift into mediocrity or mere fashion, it was Samuel Johnson who restored its moral gravity and intellectual dignity. A man of immense learning, prodigious energy, and unyielding moral conviction, Johnson embodied the final great flowering of the Neoclassical spirit — even as that spirit approached its twilight.

Born in 1709 in Lichfield, Staffordshire, Johnson’s early life was marked by both physical hardship and financial struggle. Stricken by scrofula in childhood, his appearance remained ungainly, and his movements awkward. Yet within this seemingly unpromising frame burned one of the most formidable intellects of the age. He would become not only the most influential man of letters in mid-18th-century England, but a moral force whose shadow would extend far beyond his lifetime.

Johnson’s path to literary greatness was anything but smooth. After an undistinguished tenure at Pembroke College, Oxford, cut short by poverty, he worked as a schoolmaster, then as a hack writer in London, churning out translations, essays, biographies, and parliamentary reports. It was a period of hard labour and uncertain fame — but one that forged the resilience and breadth of learning that would define his later works.

Johnson’s first major triumph came with his Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1755 — a monumental undertaking that would have daunted lesser men. Unlike modern lexicographers, Johnson worked largely alone, compiling definitions, etymologies, and illustrative quotations with heroic determination.

His preface to the Dictionary remains one of the most eloquent statements of literary purpose in English letters:

“When I took the first survey of my undertaking, I found our speech copious without order, and energetic without rules; wherever I turned my view, there was perplexity to be disentangled, and confusion to be regulated.”

This was the Neoclassical impulse at its purest — the drive to impose order upon chaos, to clarify and refine for the benefit of all. Johnson’s Dictionary not only standardised English spelling and usage; it affirmed that the language of the common people could be brought to the level of art and intellect.

Yet Johnson was more than a lexicographer. His essays in The Rambler, The Idler, and The Adventurer carried the moral authority of the Neoclassical tradition into the bustling world of periodical literature. Here, in stately prose, Johnson addressed the anxieties of modern life, the duties of virtue, and the dangers of vice, with a tone that was by turns compassionate and stern.

“Integrity without knowledge is weak and useless, and knowledge without integrity is dangerous and dreadful.”

— The Rambler, No. 174

In such lines, Johnson reaffirmed the moral vocation of literature — a mission that earlier Augustans had sometimes lost amidst the play of wit.

His great philosophical tale, Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia (1759), distilled his lifelong meditations on the human pursuit of happiness. Through the melancholy figure of Prince Rasselas, Johnson explored the vanity of human wishes, the limits of philosophy, and the inescapable burdens of mortality.

“Human life is everywhere a state in which much is to be endured, and little to be enjoyed.”

These were not the easy moral platitudes of sentimental fiction. Johnson’s vision of life was stern, compassionate, and unsparing — shaped by personal experience of illness, loss, and privation.

But it was in Lives of the Poets (1779–81) that Johnson left his final, towering literary monument. Commissioned to write prefaces for a new edition of English poetry, Johnson transformed the task into a series of masterly biographical and critical essays — works that remain models of literary evaluation and historical insight.

Johnson brought to each life a keen moral sense, a deep understanding of literary form, and an unflinching eye for human frailty. His famous verdict on Milton is typical of his balanced judgement:

“He was severe; he was parsimonious; he was imperious; he was irascible; but he was not malevolent, and he was not unkind.”

Such sentences reveal not only Johnson’s prose mastery, but his moral candour — a refusal to distort truth for the sake of literary piety.

Throughout his life, Johnson remained a figure of intellectual authority and moral gravity. His conversation, famously recorded by James Boswell in the Life of Johnson, displayed a command of reason, a breadth of knowledge, and a capacity for moral argument unmatched by any of his contemporaries.

Yet Johnson was not without contradictions. A man of deep Christian faith, he struggled with doubt and melancholy. A champion of reason, he acknowledged the limits of human understanding. A critic of sentimental excess, he possessed a heart of genuine compassion.

In many ways, Johnson embodied the last great phase of Neoclassicism — a tradition of intellectual rigor, moral seriousness, and stylistic clarity. His prose, though stately, was never pompous; his moral vision, though stern, was never cruel.

As we turn now to the prose masters of Johnson’s circle, we will see how this final generation of Neoclassical writers extended Johnson’s legacy — building works of history, biography, and political thought that would carry the Neoclassical spirit to its noble conclusion.

The Prose Masters of Johnson’s Circle

If Dr. Johnson stood as the moral centre of late Neoclassicism, he was by no means alone. Around him gathered a circle of remarkable prose writers and thinkers — men whose works extended the ideals of clarity, reason, and moral seriousness into the fields of history, biography, and political thought. Together, they ensured that the final decades of the Neoclassical era would be marked not by decline, but by a majestic maturity of English prose.

Among these figures, none towered higher in the realm of history than Edward Gibbon. His monumental work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1788), stands as one of the great achievements of English historical writing — a masterful blend of scholarship, narrative sweep, and philosophical insight.

Gibbon’s prose, though elegant, bore the marks of Johnsonian clarity. His sentences moved with a majestic cadence, balancing detail with perspective. Unlike the moralising historians of earlier times, Gibbon sought to understand history through the forces of human character, institutional decay, and cultural change — a vision deeply shaped by the Enlightenment.

His famous verdict on the fall of Rome reflects both his stylistic grace and philosophical depth:

“The decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness.”

Yet beneath this rational analysis lay a certain melancholy grandeur — an awareness that civilisations, like individuals, were subject to the laws of time and decay.

If Gibbon embodied the historian’s voice, James Boswell gave the Neoclassical world a new kind of biography — one in which the life of the subject was rendered with an unprecedented vividness and psychological depth.

In The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (1791), Boswell transformed the art of biography into something alive and immediate. His portrait of Johnson — by turns majestic, irascible, kind, and tormented — remains one of the great character studies in world literature.

Boswell’s genius lay not merely in recording Johnson’s sayings, but in capturing the man himself — the textures of his conversation, the rhythms of his thought, the struggles of his spirit. Through Boswell’s eyes, Johnson becomes immortal, not as a marble figure of moral rectitude, but as a living, breathing man of greatness and frailty.

“He talked for victory.”

Boswell’s simple yet profound observation encapsulates the force of Johnson’s intellect, his pugnacious wit, and his moral earnestness.

In the realm of political thought, the greatest prose voice of Johnson’s era was Edmund Burke. In Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), Burke composed a defence of tradition, custom, and gradual reform that still resonates with philosophical and rhetorical power.

Burke’s style combined eloquence with moral gravity. His sentences flowed with a kind of symphonic rhythm, at once persuasive and profound. Against the abstractions of revolutionary ideology, Burke championed the organic wisdom of inherited institutions:

“The age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators has succeeded.”

Here was a voice that refused the simplistic optimism of reason divorced from experience — a voice that sought to balance liberty with order, progress with prudence.

Beyond these towering figures, the later Neoclassical era saw a flourishing of serious prose across many fields:

David Hume, in his Essays, Moral and Political, brought a tone of urbane scepticism to questions of morality and governance.

Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations (1776), applied the principles of reason and observation to the complex world of commerce and society, laying the foundations of modern economics.

Richard Cumberland and others continued the tradition of the moral essay, while William Robertson advanced historical prose with a style both elegant and instructive.

Throughout these works, the core Neoclassical virtues remained visible: clarity of style, balance of judgement, moral engagement. Yet there was also a growing sense that the limits of reason alone were being reached — that feeling, imagination, and the inner life were calling for new forms of expression.

The prose masters of Johnson’s circle preserved the intellectual dignity of the Neoclassical tradition while subtly preparing the ground for its transformation. In their works, English prose achieved a level of maturity and moral depth that would stand as a beacon even as new literary winds began to blow.

As we turn now to the final section of this part — The Limits of the Neoclassical Spirit — we will reflect on the strengths and the constraints of an age that brought English letters to one of its noblest heights, even as it prepared to yield to the coming era of emotion and imagination.

The Limits of the Neoclassical Spirit

The Neoclassical Age had given English letters a legacy of order, reason, moral gravity, and stylistic clarity unmatched in its discipline and dignity. Under the pens of Dryden, Pope, Swift, Johnson, Gibbon, Boswell, Burke, and their peers, literature became not only a source of pleasure but a tool for public instruction, moral edification, and the advancement of civic virtue.

But no literary ideal can reign forever.

By the closing decades of the 18th century, the very virtues that had defined Neoclassicism — restraint, decorum, balance — began to feel, to many, like constraints. The world was changing rapidly. The industrial revolution was reshaping society. The American Revolution and French Revolution were challenging old political and philosophical certainties. In this climate of upheaval and expanding human consciousness, the Neoclassical commitment to reason and order seemed increasingly inadequate to capture the full range of human experience.

Moreover, the stylistic ideals of the age — though elevated — had often drawn literature away from the immediate voice of the heart. In the pursuit of universal truths, Neoclassical writers had sometimes neglected the particular, the personal, the emotional.

Samuel Johnson himself was deeply aware of these tensions. Though he remained a staunch defender of moral clarity and linguistic precision, Johnson also recognised that literature must speak to the whole of life — not merely to its ethical or rational aspects. His own struggles with melancholy, faith, and mortality revealed a depth of feeling that could not always find full expression within the strict architecture of Neoclassical prose.

In poetry, the heroic couplet — once the great instrument of public wisdom — had begun to feel like a gilded cage. The lyrical impulse, the voice of nature, the inner life of feeling — all were straining against the measured rhythm and satirical edge of Augustan verse.

In prose, though history and moral essays flourished, there was a growing hunger for writing that could explore subjectivity, imagination, and the complexities of human emotion.

Across Europe, new philosophical and artistic currents were stirring. The writings of Rousseau, the philosophy of Kant, the early stirrings of Romanticism in Germany — all pointed toward a coming transformation in the very conception of literature itself.

The great prose masters of the Age of Johnson remained, at heart, guardians of the Neoclassical ideal. Their works were monuments to reason, order, and moral responsibility. But even as they wrote, the winds of change were rising. A younger generation of poets and thinkers would soon sweep away the boundaries that Neoclassicism had so carefully constructed.

Yet it is important to remember that the coming Romantic revolution owed much to the age it replaced. The Romantic poets would rebel against Neoclassical form, but they would inherit its moral seriousness. They would reject its restraint, but they would continue its pursuit of universal truth. Without the intellectual rigor and moral gravity of Dryden, Pope, Johnson, and their successors, the Romantic impulse toward lyrical freedom might have dissolved into mere sentimentality.

Thus, as we close the scroll on the Age of Johnson, we must do so with a recognition of both its greatness and its limits. It was an age that taught English writers to value clarity, precision, and moral vision — gifts that no future age would wholly discard. But it was also an age that, in its pursuit of these ideals, often forgot the primordial power of imagination, the wild music of the heart, and the deep song of nature.

These were the gifts that the next literary era — the Pre-Romantics — would strive to recover.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance