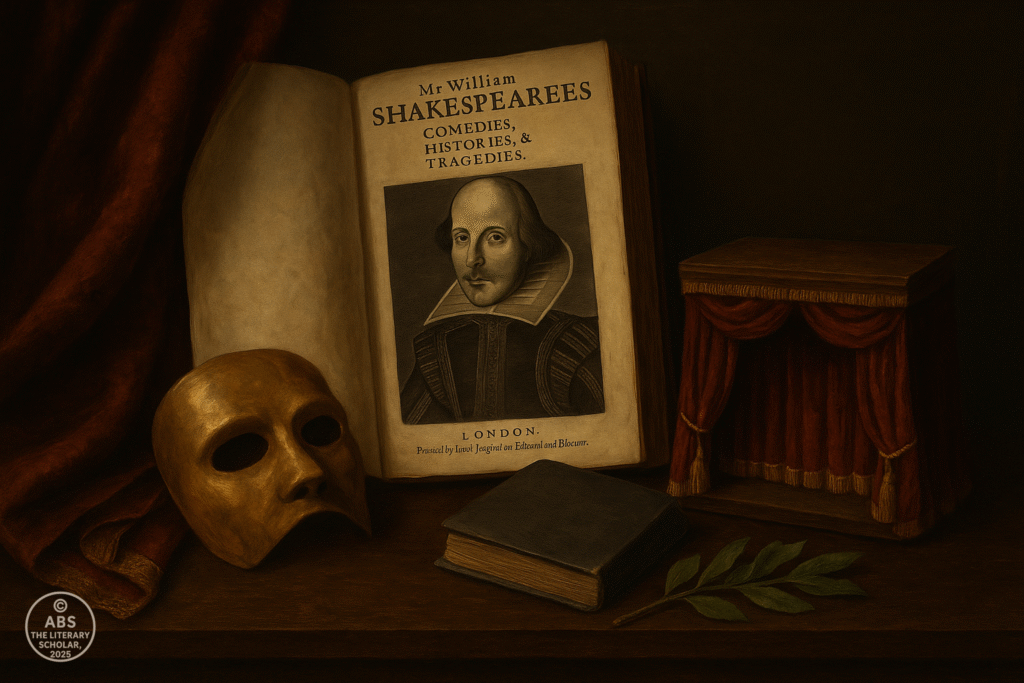

England’s Golden Age and Gathering Shadows Part 4: The Last Act — England’s Stage Faces the Final Curtain

The Silenced Stage — Theatres in Crisis and Private Voices

From The Professor's Desk

A Nation Divided, a Stage in Peril

“It is an old trick of time: even as the curtain rises for one act, the scenery behind it is already being struck. So it was with England’s stage, glorious still to the eye, but trembling on hidden faultlines.”

The year was 1625. A new monarch, Charles I, had ascended the English throne upon the death of his father, James I. The golden light of the Elizabethan and Jacobean stage had not yet fully dimmed; London’s theatres still echoed with voices — though no longer Shakespeare’s, for his hand had been stilled nearly a decade past.

Ben Jonson, that grand old lion of letters, still roared through masques and court poetry. Playhouses such as Blackfriars and The Fortune continued to draw their faithful, and the King’s Men performed with courtly patronage. Yet beneath the boards, the ground was shifting.

England was no longer the confident, expansive realm it had seemed under Elizabeth. The memory of the Armada victory had faded; new tensions gripped the land.

Religious fractures deepened, pitting Anglicans, Puritans, and Catholics in increasingly bitter contests.

The economy strained under war taxes and royal mismanagement.

Parliament and king eyed one another with growing distrust.

And amid these larger storms, the theatre, that once-proud vessel of national imagination, sailed into troubled waters.

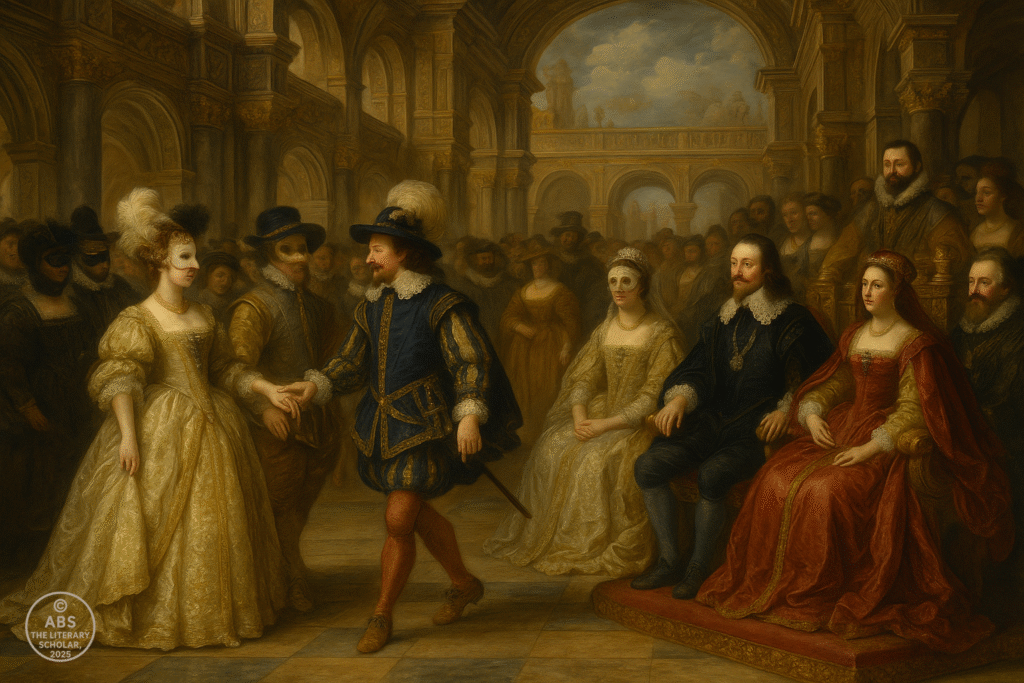

At first, Charles I seemed a natural patron of the arts. A lover of painting, music, and courtly spectacle, he presided over a rich culture of masques, designed by the genius of Inigo Jones and penned by Jonson and others.

But herein lay the first subtle shift:

Where Elizabeth’s and even James’s courts had embraced the public theatre, Charles’s favoured private, courtly entertainments. The masque, with its carefully choreographed grandeur and coded political flattery, became the dominant form — its exclusive audiences drawn from the nobility.

The public theatres, meanwhile, grew increasingly suspect in the eyes of moralists and Puritan leaders. The very qualities that had once made them beloved — their bawdy humour, sharp satire, and mingling of classes — now appeared as signs of corruption to those who sought a more godly commonwealth.

And the public itself grew anxious. Whispers of religious tyranny, fears of foreign wars, economic hardship — all began to cloud the festive mood that had once filled the playhouses.

Yet the players remained. They performed still, if more cautiously. Playwrights, sensing the winds, trimmed their themes; the grand histories and political dramas of Shakespeare’s day gave way to comedies of manners and romantic intrigue — safer ground in an increasingly volatile age.

But it was a fragile balance, and beneath it, the stage trembled.

As the 1630s progressed, the Puritan voice grew louder. In Parliament, in pulpits, and in print, attacks upon the theatre multiplied. It was no longer mere scorn; it was a rising tide of moral outrage, gathering force.

And as we shall soon see, that tide would soon sweep away the very boards upon which England’s greatest words had once been spoken.

Charles I’s Court and Culture

“When the king’s gaze turned inward, the theatre’s voice grew fainter—still eloquent, still defiant, but no longer at the center of the nation’s dreaming.”

It is one of the great ironies of history that Charles I, perhaps the most aesthetically cultivated monarch England had yet known, should reign over the slow unravelling of its first great theatrical age.

In the early years of his reign, Charles seemed every inch a patron of the arts. His court glittered with the canvases of Van Dyck, the architecture of Inigo Jones, and the intricate staging of court masques — events so elaborate they blurred the line between theatre and ritual.

These masques were no simple entertainments. They were political performances, crafted to reinforce the image of a harmonious, divinely ordered monarchy.

Through dance, allegory, and visual splendour, they presented an ideal England — one in which Puritans, radicals, and Parliamentarians conveniently did not exist.

Yet this very turn toward private court culture marked a subtle betrayal of the public stage.

The playhouses of London, where for decades commoner and courtier alike had shared the spectacle of Falstaff’s wit, Lear’s madness, and Macbeth’s ambition, now stood at an increasing remove from royal favour.

Charles’s court funded masques, not the King’s Men or the Queen’s Men. It staged allegories of unity, not the dangerous ambiguities of public drama.

Meanwhile, outside the gilded halls, the mood was shifting.

The public theatre remained vibrant through the late 1620s and early 1630s. The King’s Men, now led by actors such as John Lowin and Joseph Taylor, continued to perform Shakespeare’s works and new plays by the likes of Philip Massinger and James Shirley.

Yet the tone of drama subtly changed:

Fewer political plays, more romantic comedies.

Less social satire, more safe moral tales.

Playwrights watched their words carefully, knowing that both censors and sermons waited to seize upon any perceived offense.

Even so, the theatres drew crowds. The love of the English people for the stage was not so easily extinguished.

But beyond the playhouses, the ground was shifting fast:

In Parliament, Puritan influence grew bolder.

In pulpits, sermons railed against masques and stage plays alike.

In pamphlets, anonymous voices decried the immorality of actors, the blasphemy of theatre, and the mingling of social classes in the galleries.

And all the while, Charles, more isolated than he understood, turned ever inward — to court spectacle, to divine right, to art as self-affirmation rather than as public dialogue.

Thus the stage stood increasingly alone:

Once a proud mirror to the nation, it now reflected a kingdom growing harder to comprehend, and a monarchy increasingly unable to hear its voice.

The players played on, as they always had. But they knew the tune was changing. And soon, the music would be stopped altogether.

The Rise of Puritan Hostility – The Theatre Under Siege

The velvet curtains of the Elizabethan stage now fluttered under a colder, sterner wind.

While the early Stuart period still basked in theatrical afterglow, a gathering storm threatened the glitter of the playhouse. The Puritans — that stern, scriptural, and disapproving force — began rising in influence, casting a long shadow over the carefree mirth of drama.

They weren’t just disapproving.

They were furious.

To them, the theatre was “the Devil’s Chapel,” where the sins of vanity, idleness, and lust strutted about in verse. And so began a cultural conflict of biblical proportions — Bacchus vs. the Bible.

Theatrical companies, once the darlings of Elizabeth and James, found themselves vilified in sermons and outlawed by edicts. Sunday performances? Blasphemous. Cross-dressing actors? Abominations. Mirth and laughter? Tools of Satan, obviously.

“Plays do allure the people from piety and godliness,” thundered one such Puritan preacher,

“and stir them up to whoredom, pride, and uncleanliness.”

Charming fellow.

By the 1630s, this hostility began taking legislative form. Laws were passed to restrict stage content, regulate performance times, and tax the troupes into poverty.

But the theatre didn’t go down quietly.

Enter Ben Jonson, whose later works like The Magnetic Lady (1632) and A Tale of a Tub (1640) brimmed with defiance. His pen, even in old age, carved satire into Puritan hypocrisy. But the audiences were dwindling. So were the patronages. And the once-thriving playhouses began to look like ghosts of revelry past.

By 1642, the Parliament (now Puritan-heavy) ordered all theatres shut.

And the lights dimmed on a golden age.

Not because the people stopped loving plays,

but because the ruling class had decided they shouldn’t.

The stage was silenced. But the anger it caused? That was still very much alive.

Parliament vs. Monarchy – The War of Authority

If Elizabeth’s reign was a golden masque, Charles I’s was a slow-moving Greek tragedy—complete with pride, betrayal, and an execution in Act V.

The cracks began to show the moment Charles I ascended the throne in 1625. Unlike his pragmatic father, James I, Charles believed in the Divine Right of Kings — the idea that monarchs were God’s chosen vessels, not to be questioned by mere mortals (or Parliamentarians). Which sounds divine… until you run out of money.

And Charles, naturally, did.

To fund wars and royal flair, Charles turned to Parliament for taxes. But Parliament, emboldened by decades of constitutional whisperings, had grown a spine. They demanded rights. Checks. Balance.

Charles responded by doing the most Charles-like thing imaginable:

He dissolved Parliament. Multiple times.

By 1629, he ruled without it altogether in a glorious stretch of kingly tantrum known as the Eleven Years’ Tyranny — also called Personal Rule. During this time, he governed alone, raised illegal taxes like Ship Money, and appointed Archbishop Laud, a man whose love for elaborate rituals nearly equaled his talent for making enemies.

Meanwhile, Puritan resentment was stewing. The moral rigor of the commons clashed with the ritualistic pomp of the crown. Parliament was no longer just a legislative body. It was an idea — one that refused to kneel.

And then came 1637, when Charles made the ultimate blunder:

He tried to force the Anglican prayer book on Presbyterian Scotland.

Spoiler: The Scots didn’t love that.

This led to the Bishops’ Wars, which led to desperate finances, which led to Charles recalling Parliament in 1640. And once back, Parliament had receipts. Centuries of them.

“No more kingly tantrums,” Parliament essentially said.

“We’re staying. Permanently.”

Thus began the Long Parliament — and the long road to civil war.

The country was split not just geographically, but philosophically:

Cavaliers — the king’s supporters, aristocratic and courtly —

vs.

Roundheads — Parliament’s army, led by sober men in black and eventually, one very intense Puritan named Oliver Cromwell.

This was not merely a political tussle.

It was the unraveling of an era.

Theatres had gone dark.

Faith had turned factional.

And now, even the Crown was trembling.

The English Civil War was not the end of the Renaissance,

but it was the sword that severed its last golden threads.

Theatres Under Siege — The Final Curtain Falls (1637–1642)

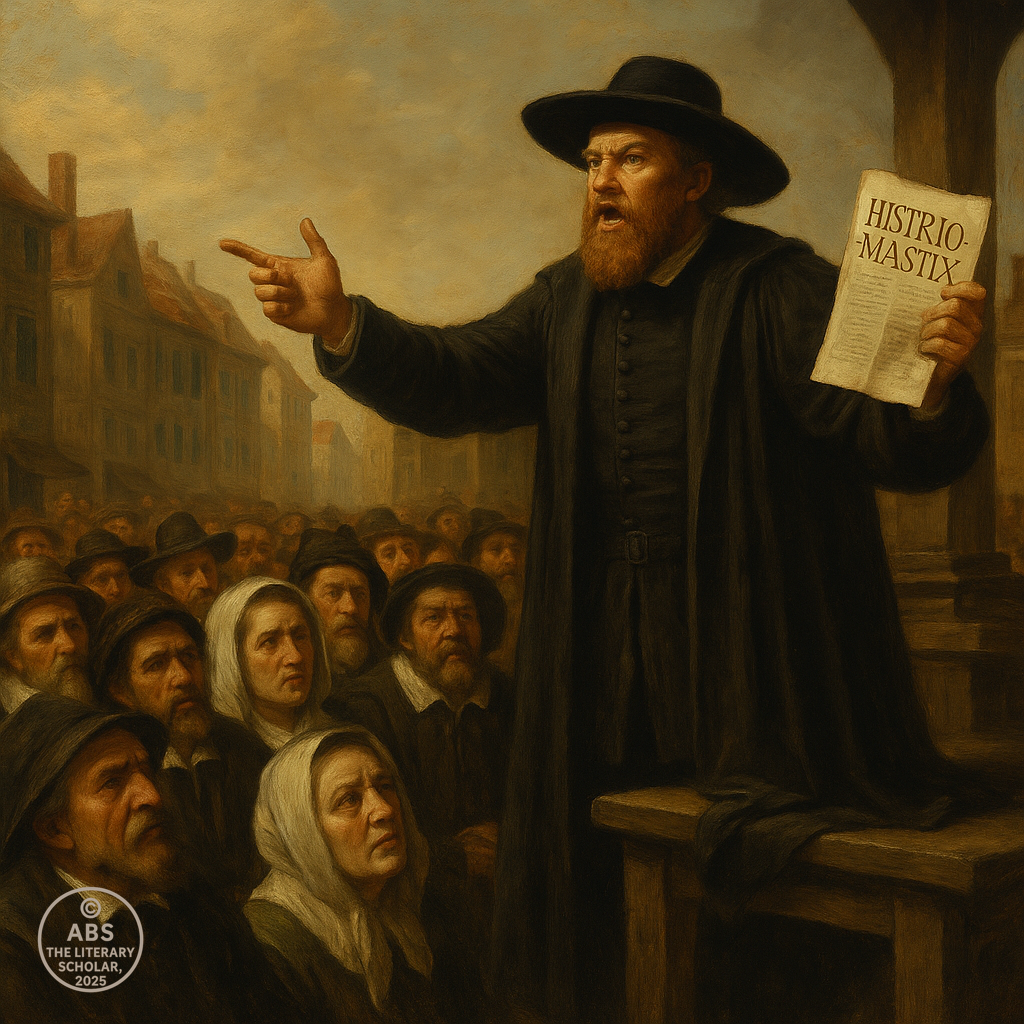

By the late 1630s, the flourishing world of Renaissance drama had begun to resemble a stage lit for its own funeral. The once jubilant echo of Shakespearean verse and the poetic thunder of Jonsonian satire now struggled to be heard over the rising crescendo of Puritan disapproval. And it wasn’t subtle. These were not minor critics frowning politely from the shadows. These were fire-breathing moralists who believed theatre was a spiritual infection—worse than plague, because at least the plague didn’t wear tights.

As the cultural climate turned cold, England’s theatre community found itself battling not just censorship, but a full-blown ideological assault. Pamphlets flooded the streets, pulpits roared, and printed tirades with titles like “Histrio-Mastix: The Player’s Scourge” painted actors as hell’s footmen and playwrights as Satan’s secretaries. The Globe Theatre, once a cheerful amphitheatre of laughter and sword fights, was suddenly a den of iniquity. According to Puritan standards, it was a sinful circus luring good Christians into the arms of poetic temptation and bawdy humour.

Behind the scenes, covert laws, moral crackdowns, and strict censorship began tightening the noose. Court masques declined, playwrights turned cautious, and even the King’s Men, once favoured by royalty, found themselves increasingly alienated. It wasn’t just about religion anymore—it was a civilizational tug-of-war, with art, entertainment, and free expression caught in the crossfire. Tragedy became subversive. Laughter, almost criminal. And iambic pentameter? Practically heresy.

Then, in 1642, the end came not with a soliloquy, but a solemn decree. The Long Parliament, dominated by Puritan influence, issued an ordinance:

“That public stage-plays shall cease and be forborne.”

And with that, the curtains fell.

Theatres were closed.

Playhouses boarded.

Troupes disbanded.

Scripts buried in drawers.

The Golden Age of Elizabethan theatre—that glittering epoch of poetic thunder, tragic grandeur, and comic wit—was now a haunted relic. The wooden O of the Globe fell silent. The stage lights of England’s most vibrant cultural moment flickered out—not by artistic failure, but by moral decree.

The final curtain had fallen, and a long, sombre intermission was about to begin.

Closing Note: The Golden Age Dims — A Curtain Call for an Era

And so, with the last theatre shuttered and the final verse silenced, the golden age of English literature—stretching from the radiant court of Elizabeth I to the politically fractured reign of Charles I—draws its long, luminous arc to a close.

We have walked the gilded courts of Spenser and Sidney, wandered the philosophical groves of Bacon, traced the tempests of Shakespeare, and trembled beneath the dark velvet skies of Webster and Ford. We have seen the sonnet evolve, the drama erupt, the masque dazzle, and the pen challenge power itself.

It was an age of linguistic fire and intellectual fearlessness, where writers dared to immortalize love, question authority, sketch kings, jest with fools, and lift the English language to architectural grandeur. From the lofty platonic ideals of Sidney to the grim fatalism of the Caroline dramatists, this era housed a civilisation intoxicated with its own eloquence.

But as the ink dried and the quills fell still, England changed. The dreams of the Renaissance turned brittle under the strain of political dissent and religious rigidity. The civil wars loomed, the parliament stirred, and the sound of rhetoric was soon to be replaced by the rhythm of marching boots.

This, then, is the final act of a remarkable performance.

The Elizabethan and Jacobean stages may be dark,

But their shadows fall long across the centuries.

From the Desk of ABS, The Literary Professor

A time will come when we speak of Commonwealths, Puritan austerity, and the poetry that survived without applause. But let us, for a moment more, stand still—here—at the edge of the last candlelit theatre, where Hamlet still broods, Lear still rages, and poetry still believes in kingdoms.

The scroll closes not in sorrow, but in reverence.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Professor

Where the past speaks in paragraphs, and the silence between eras is a story in itself.