When theatres were dark, and words learned to walk in prose and prayer.

From The Professor's Desk

“The golden mask was folded. The curtain was drawn. But England was not yet done with drama—only its public stage. What followed was an era of silence, of pamphlets over plays, of sermons over soliloquies. It was a time when the sword ruled the land, and the pen fought to remember what the tongue dared not speak. This was the Puritan Interregnum: when Milton’s words blazed and dramatists waited in the shadows.”

England Torn: The Road to Regicide

The English stage had barely fallen silent when the entire kingdom began to sound like a tragic chorus. If the Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre had made England the world’s most vibrant drama-house, the 1640s would make it an unlit theatre of blood and ink. And as every scholar must pause to reflect — what happened between courtly sonnets and scaffolded kings is as much literary story as political fact.

The actor who strode most dangerously into this fatal play was Charles I, a king as ill-suited to his part as any miscast tragic hero. Son of the clever James I, Charles possessed a dangerously divine view of kingship, a blind faith in the absolute power of the crown, and a disastrous incapacity to read the temper of his audience — the people and their Parliament. In the drama of England, Charles insisted on playing the role of God’s anointed king, even when the crowd began hissing from the pit.

For more than a decade, from 1629 to 1640, Charles ruled without Parliament, dissolving it in a fury over money and religious conflict. His Personal Rule became an exercise in monarchical censorship — not only of politics, but of the press itself. The Star Chamber enforced harsh control over what could be printed. Books were seized. Printers jailed. The poets and playwrights who had once poured forth their art under Elizabeth and James now found themselves operating under a narrowing, chilling gaze.

But the English pen is a stubborn instrument. As Parliament was called again in 1640 amid rising Scottish rebellion, and as Civil War cracked open the old order, the printing presses exploded with pamphlets and arguments from every side.

It was in this turbulent age that a brilliant Latinist, poet, and moral visionary named John Milton strode into public discourse. Milton, already a literary force, now became a polemicist of conscience. When Parliament, having abolished the Star Chamber, itself attempted to revive the licensing of books in 1643, Milton thundered back with Areopagitica — that sublime plea for liberty of the press:

“Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.”

Here was a voice that soared beyond party, beyond faction — a voice that defended the eternal dignity of the written word against the passing tyrannies of kings and parliaments alike. But liberty, in the streets of England, was bleeding into anarchy.

By 1642, with the kingdom fractured between Royalists and Parliamentarians, the conflict burst into civil war. Cavaliers — with flowing locks, swords, and a vision of a gallant England — marched beneath the banner of Charles. Roundheads — sombre, steeled with Puritan purpose — fought for Parliament and godly rule. As the battles raged — Edgehill, Marston Moor, Naseby — the Parliament in London struck another fatal blow to the arts.

In September 1642, an ordinance ordered that all theatres be closed, condemned as “nurseries of licentiousness.” The theatres that had echoed with Shakespeare’s verse and Ben Jonson’s wit now stood dark. Actors dispersed. Playhouses shuttered. The vibrant stage that had mirrored England’s soul became a hollow, silent shell.

And then came the unthinkable.

In 1646, Charles surrendered. A captive king. Yet the conflict deepened. The Parliament itself split; the army — radical and Puritan — grew restless. Now the drama of the scaffold approached.

In January 1649, Charles I was brought to trial — an event so unprecedented that the world watched in stunned silence. Here was a monarch, tried by his own subjects, facing the charge of treason against the realm. Charles, for all his flaws, stood with tragic dignity. “A subject and a sovereign are clean different things,” he insisted. Yet the tide of revolution would not be stayed.

On 30 January 1649, on a cold scaffold in Whitehall, Charles I laid his neck upon the block. The axe fell. The king was dead. And the mask of monarchy had been stripped from the English stage.

Europe gasped in horror. Kings shuddered. But for England’s poets and writers, a new and chilling question arose:

If the axe can fall upon a king, how safe is the poet’s tongue?

In the days and weeks that followed, poetry became elegy. The great Royalist poets mourned their king, often in coded verse:

“I saw him die, yet now I live to say,

The traitor cannot triumph, though he slay.” — Richard Lovelace

Thus began England’s strangest theatrical age — a nation where the theatres were dark, yet the true stage had become the printed page, the private chamber, the whispered song. And from this moment of regicide, a new political and literary experiment would stagger forth — the Commonwealth.

But even as the saints prepared to rule, the pen had learned to resist, and England’s writers would not be so easily silenced.

The Commonwealth Ascends — Rule of the Saints

The axe had fallen, and the mask of kingship had been torn away, yet what emerged from the bloodied scaffold was no gentle republic of letters and liberty, but a new and harsher order. The dream of freedom that had driven many pens and swords soon gave way to the weight of a government ruled by saints and soldiers.

In the wake of Charles I’s execution, England stood not in triumph, but in uneasy silence. A Commonwealth was declared, a republic by name, yet the air was thick with sermons, edicts, and the acrid scent of fear. Parliament’s victory had been purchased at a dreadful cost, and now it faced the task of governing a fractured land. Over this fragile new state, one figure would soon cast a long shadow.

Oliver Cromwell, the general whose armies had won the war, now became the conscience and controller of the nation. Though not crowned, he held a power more absolute than many kings before him. Cromwell, a man of deep religious conviction, believed he had been chosen by Providence to guide England into a godly future. His was a Puritan vision, stern and ascetic, where the pleasures of the body were suspect, and the frivolities of art were deemed corrupt.

Thus began the long winter of English public culture. Theatres remained closed by law, condemned as dens of vice. Dancing was discouraged, music softened under Puritan scrutiny, and even Christmas itself was banned as a popish festival. Public life grew bleak and moralised, its colours faded beneath the drab cloak of enforced virtue.

Yet, paradoxically, the Commonwealth unleashed a torrent of words. The printing press, though monitored and censored, became the arena where England’s competing visions clashed and combined. Pamphlets poured forth in staggering numbers, their pages crackling with political argument and religious fervour. In every market square and tavern, the people debated the merits of the new republic, the justice of the king’s execution, and the future of the nation.

Amid this cacophony of voices, John Milton rose as the most brilliant and complex pen of the age. Having defended the trial and execution of the king, Milton now took office as Secretary for Foreign Tongues, a role that made him the official Latin voice of the Commonwealth to the courts of Europe. It was a grim task. Milton, whose vision had been one of a free and virtuous republic, now found himself defending an increasingly authoritarian regime.

In the chill of these years, his prose grew sharper, more sorrowful, and more prophetic. The Areopagitica, written earlier in protest against licensing laws, remained a defiant beacon, though its plea had not been heeded. The Commonwealth continued to censor the press, fearful of Royalist propaganda and radical dissent alike.

Milton’s Eikonoklastes, written in response to the Royalist Eikon Basilike, sought to dismantle the image of the martyred king, though Milton, no less than his opponents, understood the profound symbolic power of words. His Defensio pro Populo Anglicano defended the right of the people to overthrow a tyrant, yet in doing so, revealed his growing awareness of the tragic complexities of revolution.

As Cromwell’s power deepened, crowned in effect if not in ceremony, Milton watched with an inwardly torn heart. He had fought for liberty of conscience, for the dignity of the written word, and for a republic of moral virtue, but the reality that emerged was one of military rule and religious intolerance.

And so, while pamphlets multiplied and sermons thundered from every pulpit, a deeper silence settled over England’s artistic life. The public theatre was gone, its actors scattered, its stages dark. Music was muted, painting grew austere, and architecture lost its ornament.

Yet beneath this surface of grim conformity, new literary forms were stirring. Prose gained a sharper edge, poetry turned inward, and the imagination, denied the stage, found refuge in the private chambers of closet drama.

Thus the Commonwealth, for all its moral certainty, failed to extinguish the English literary spirit. In attempting to bind the nation in the chains of piety, it inadvertently set the stage for a more subtle, more resilient form of resistance, one that would speak in poetry and prose, in whispers and in songs.

And at the heart of this defiant undercurrent stood Milton, blind but unbroken, preparing in darkness the epic that would outlast both kings and protectors.

Milton: The Pen of a Revolution

In the dim corridors of the Commonwealth, where sermons rang louder than sonnets and the sword often silenced the pen, one voice rose with a fire that no tyranny could extinguish. That voice belonged to John Milton, poet, polemicist, and, above all, moral conscience of a nation at war with itself.

Milton had long been a solitary figure in England’s literary landscape, his early works suffused with classical grace and spiritual intensity. Yet the turbulence of the 1640s transformed him from a scholar of sublime verse into a fierce champion of liberty. The poet who had once wandered through the groves of Arcadia now strode boldly into the forum of public debate.

When Parliament, having abolished the Star Chamber, attempted to impose its own licensing order on the press in 1643, Milton responded with a blast of oratory that has echoed through the centuries. His Areopagitica, a pamphlet as brilliant in style as in substance, defended not merely the freedom of the press, but the very principle of intellectual liberty:

“Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.”

It was a call to arms for the mind, a beacon of thought in an age of dogma. Yet Milton’s words, though admired, did not sway the guardians of the new moral order. Licensing remained, and with it, the shadow of censorship.

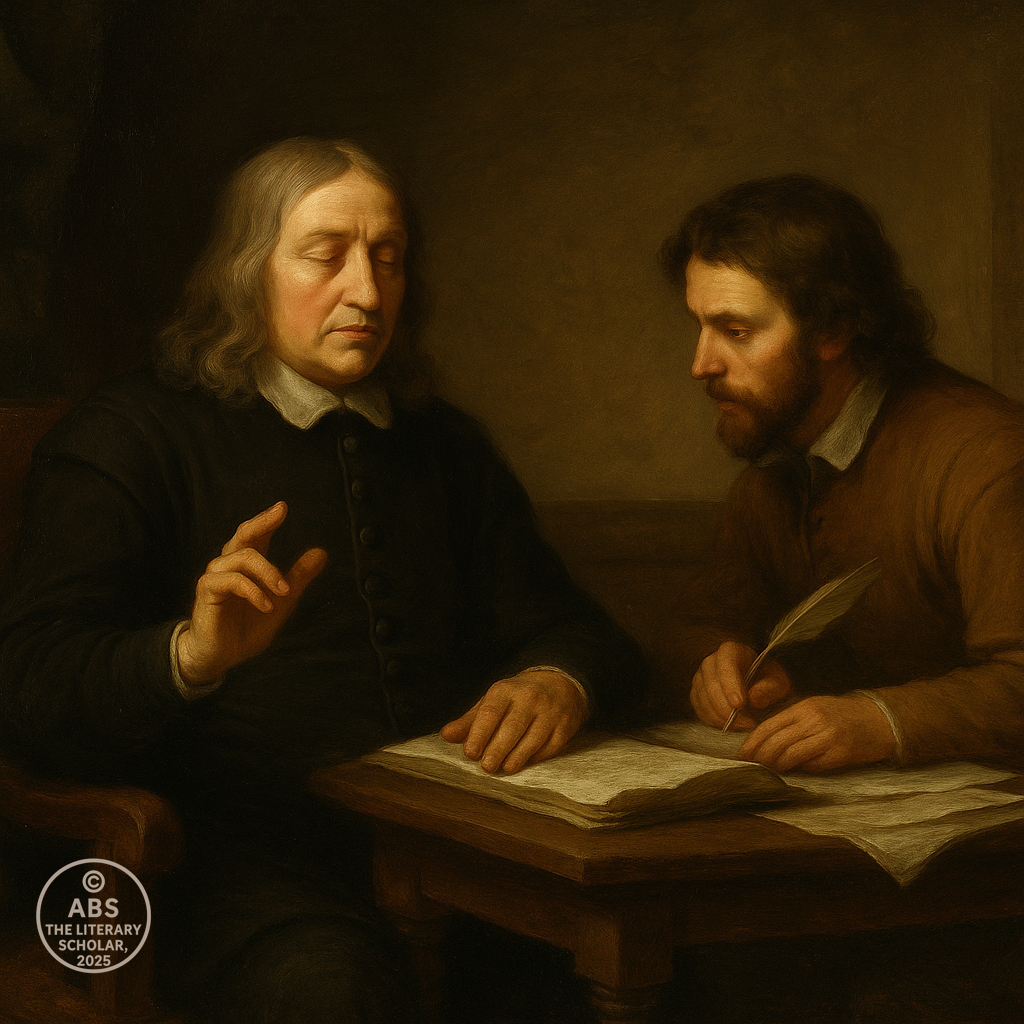

As the republic took shape from the ruins of monarchy, Milton, driven by both duty and idealism, accepted the role of Secretary for Foreign Tongues in Cromwell’s government. Here, in the cold machinery of statecraft, he defended the regicide and the nascent Commonwealth before the courts of Europe.

His Eikonoklastes, written in the raw aftermath of Charles I’s execution, dismantled the cult of the martyred king with a fierce logic that cut through the sentimentality of Royalist propaganda. Yet as Milton penned these defenses, a deeper struggle stirred within him.

He had dreamed of a republic of free men, a government of reason and virtue. What emerged, however, was a republic of fear, where the military ruled, and the saints imposed their narrow vision upon the land. Cromwell’s ascent to Lord Protector in 1653 marked a bitter turn, for though Milton respected the man’s strength and sincerity, he recoiled from the creeping authoritarianism that followed.

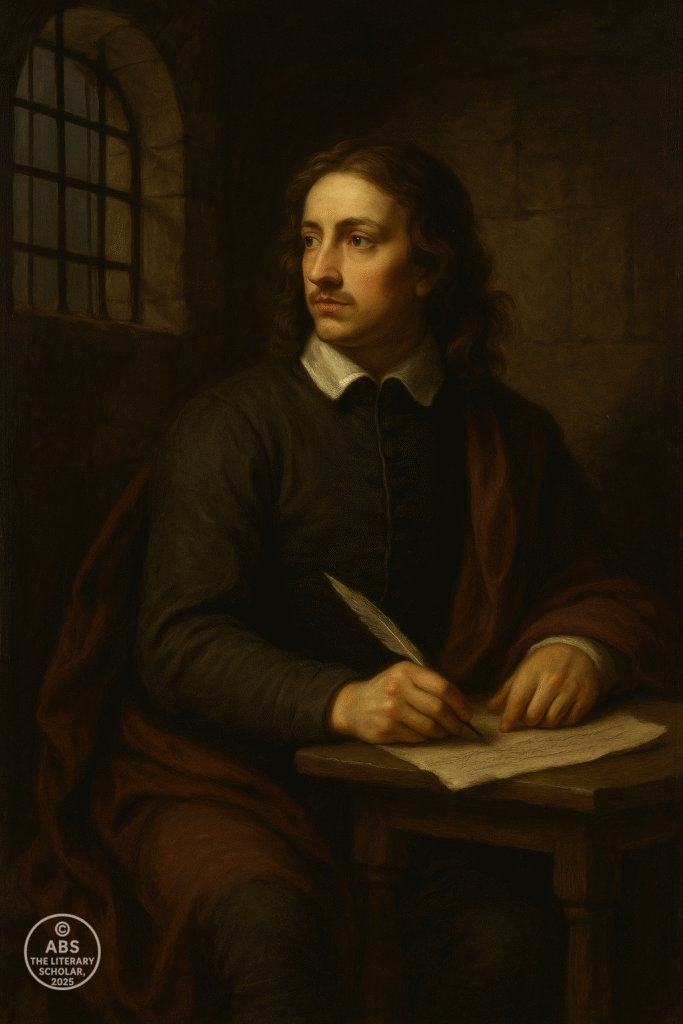

As if fate sought to deepen his inward exile, Milton lost his sight during these years. The poet of soaring visions was now condemned to darkness, his physical world dimmed even as his inner eye blazed with undiminished light.

“When I consider how my light is spent,

Ere half my days in this dark world and wide…”

Yet blindness did not still his voice. Dictating to secretaries and family members, Milton continued his labours. His Defensio pro Populo Anglicano, written in Latin, stood as a proud defense of the people’s right to overthrow tyranny, even as his own government veered towards it.

In these sombre years, Milton’s poetry grew richer and more profound. The sonnets composed during the Interregnum bear witness to a mind grappling with loss and longing, with public duty and private sorrow. And deep within this crucible of personal and national turmoil, Milton began to conceive the work that would immortalise him beyond the reach of any political cause.

Paradise Lost, though not published until after the Restoration, was forged in these dark days. Its themes — the fall of the angels, the tragedy of lost perfection, the complexity of free will — mirrored the moral ambiguities of England’s revolution. In Satan, noble in defiance yet doomed by pride, in Adam and Eve, frail in innocence yet resilient in hope, Milton captured the essence of his time, when lofty ideals had tumbled into harsh realities.

Blind, disillusioned, yet undaunted, Milton became the living paradox of the Puritan Interregnum. A defender of the republic who mourned its betrayals, a Puritan who cherished art, a revolutionary who revered tradition, a man of vision in a world gone dim.

Through his pen, the conscience of England spoke, sometimes in trumpet blasts of polemic, sometimes in the solemn music of epic verse. And though the Commonwealth’s political edifice would soon crumble, Milton’s legacy, born of fire and shadow, would endure, a testament to the power of the written word to transcend the fleeting dominion of kings and protectors alike.

Now, beyond the fierce clarity of Milton’s voice, we must turn to those who wrote from loss, exile, and longing — the Royalist poets, whose defiant verses whispered against the dark.

The Poets Who Defied — Royalists in Exile and in Verse

Even as Milton’s blind pen defended the republic with the force of a prophet’s voice, there remained another, softer current of resistance, flowing through the dark rivers of England’s literary soul. It whispered not from the pulpits of the victorious Puritans, nor from the official presses of the Commonwealth, but from the embattled hearts of the Royalist poets, scattered in exile, imprisoned in cold stone cells, or writing in secret within their shuttered homes.

For these men, and sometimes for the women beside them, the execution of Charles I had not ended a reign, it had ended a world. The courtly culture of the Stuarts, with its love of wit, elegance, loyalty, and song, had been swept away beneath the iron tide of Puritan severity. Yet the Royalist pen refused to break. Instead, it turned inward, crafting verses of longing, loyalty, and coded defiance. Poetry became both a lament and a weapon, preserving a vanished England within the fragile permanence of the written word.

Among these voices, none rang more poignantly than that of Richard Lovelace, the soldier-poet whose pen and sword had both served the king. Imprisoned for his loyalty, Lovelace wrote from his cell with a freedom that no iron bars could diminish. In his celebrated poem To Althea, from Prison, the lines remain immortal:

“Stone walls do not a prison make,

Nor iron bars a cage.”

Here, defiance rose not in trumpet blasts but in the quiet music of a spirit unbroken. Lovelace transformed captivity into a stage for the triumph of mind over matter, of honour over oppression.

Another voice of the vanquished was Robert Herrick, the country parson who had once flourished amid the courtly circles of Charles I. His poetry, collected in Hesperides, sings with the rich sensuality and human warmth that the Puritan world sought to extinguish. The famous lines of his carpe diem lyric echo with both celebration and subtle defiance:

“Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying.”

Though not a direct political statement, Herrick’s verse preserved the joyous spirit of a lost England, an England of song and laughter, now condemned as sinful by the ruling saints. In each tender lyric, the old cavalier world breathed quietly beneath the new regime’s stern gaze.

The witty and rakish Sir John Suckling, too, left behind verses that masked sorrow with elegance. His playful poem Why so pale and wan, fond lover? seems a mere love lyric, yet beneath its teasing tone lies the melancholy of a courtier whose entire cultural world had collapsed.

Denied the public theatre, the drama of the Cavaliers found refuge in a subtler form: closet drama. These were plays written not for the stage, but for private reading, an act both literary and political. One of the most ambitious such works was Sir William Davenant’s Gondibert, a philosophical epic in dramatic form. Davenant, who had once crafted masques for the royal court, now poured his energies into a drama meant to be read in secret chambers, where the flicker of candlelight might yet revive the spirit of England’s lost grandeur.

Even Milton, despite his Puritan allegiance, would later contribute to this hidden tradition with his own Samson Agonistes, a tragic meditation on bondage, loss, and the complex nature of freedom. In its lines, the parallels with England’s fallen Cavaliers are inescapable.

“Eyeless in Gaza, at the mill with slaves.”

The Royalist poets, whether in exile, prison, or silence, wove a tapestry of resistance through verse. Their poems mourned a king, a culture, a vision of England that had vanished beneath the grey shroud of the Commonwealth. Yet in mourning, they preserved.

Every couplet, every sonnet, every whispered song became an act of cultural defiance, a refusal to let the vibrant soul of England be entirely erased. And as manuscripts passed from hand to hand, as lines were committed to memory and shared in quiet gatherings, the poetic imagination endured.

The Cavaliers had lost the war, but through their poetry, they ensured that the lost world of honour, beauty, and loyalty would haunt the Puritan peace. Their verses carried forward the spirit of a nation that awaited a king, and when that king would return, it would be these voices, half-buried but never stilled, that would help rekindle the light of English letters.

Now, beyond the mournful strains of the Royalist poets, another quieter revolution had begun, as voices long suppressed by custom and law began to find their place upon the page — the women of England had begun to write.

The Women Who Wrote in the Shadows

In the shadowed interregnum of England, where the public theatre had been silenced, the music of masques muted, and the great voices of the Cavaliers scattered to wind and exile, another quieter chorus began to rise. It came not from the royal court, nor from the Puritan pulpit, but from an unexpected quarter — the private chambers and writing desks of women.

For centuries, the female voice in English letters had been marginalised, confined to devotional verse or the occasional translated text. The great public forums of poetry, drama, and intellectual debate remained largely the domain of men. Yet paradoxically, the closure of the theatre and the policing of public literary life created new spaces where women’s pens could flourish, often beyond the scrutiny of the saints who ruled the land.

When the public voice is silenced, the private voice grows bolder.

And so it was that, during the Commonwealth, a remarkable flowering of women’s writing began, as England’s literary culture retreated from the streets into the parlours and libraries where women had long been consigned, not as creators but as readers. Now they began to write.

Among the most dazzling of these voices was Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, a figure as brilliant as she was eccentric. The daughter of a wealthy Royalist family, Cavendish had known the splendours of court life before exile thrust her into France. Yet exile seemed only to ignite her restless imagination.

Bold in mind, unafraid of ridicule, Cavendish returned to England determined to carve out a literary space for herself in a culture still reluctant to grant women the role of public intellectuals. She wrote with astonishing range — philosophy, poetry, fiction, and scientific treatise — refusing to be bound by the narrow expectations of her sex.

Her prose often overflowed its formal bounds, her style wild, unapologetic, at times chaotic. Yet in works like The Blazing World, she gave birth to one of the earliest works of science fiction, a visionary text that dared to dream of a female-created utopia.

“My ambition is not only to be Empress, but Authoress of a whole World.”

This was no mere courtly phrase. Cavendish’s ambition was immense, her courage greater still. In an age where Puritan morality sought to still the arts and where women were expected to content themselves with piety and silence, she dared to write philosophy in print, to dispute with Descartes and Hobbes, and to publish her own collected works under her name.

If the theatre had been banished from England’s streets, it had not been banished from Cavendish’s mind. In her dramas and prose, the imagination of theatre lived on, now housed in a woman’s words.

If Cavendish was England’s literary comet, blazing across the dark sky of the Commonwealth, Katherine Philips, known as “The Matchless Orinda,” was its gentle, unwavering star. A poet of friendship, loyalty, and measured reflection, Philips carved out a space for women’s verse that was at once personal and politically aware.

Within her literary circle of women — a remarkable early form of literary sisterhood — Philips wrote poetry that explored the deep bonds of female friendship, elevating it to an art worthy of public respect. Her language was controlled, elegant, suffused with quiet strength.

Yet beneath the polished surface of her verse lay a Royalist heart. While avoiding overt political statement, Philips’s poetry often mourned the loss of a world where courtly values and artistic expression had once flourished. In poems addressed to her friends, she wove threads of grief for the England that had fallen into the grip of Puritan austerity.

“First friendship, then affection’s softest name,

Shall dignify the passion I proclaim.”

In her controlled, almost chaste language, one hears the deeper currents of loss and longing, of a poet writing within the constraints of her time, yet claiming her place upon the literary stage with quiet, persistent dignity.

Beyond Cavendish and Philips, many other women wrote during these years, often in forms still deemed “acceptable” for their sex — letters, memoirs, religious meditations. Yet in these ostensibly private genres, they began to test the boundaries of expression. Diaries became acts of self-authorship. Letters became instruments of political commentary. Devotional verse became a space where spiritual longing and personal identity could intertwine.

The Commonwealth’s suppression of public artistic life, intended to purify the nation, had inadvertently opened doors behind closed doors. In the absence of public theatre and courtly spectacle, the domestic space itself became a stage for literary creation.

The pen, once the exclusive sceptre of the learned male, was now taken up by women who refused to be silenced. And though few could openly publish in the fraught climate of the Interregnum, their words circulated through manuscripts, through correspondence, and later, through printed collections that would shape the course of English letters.

In seeking to still the song of England, the saints had inadvertently taught women to sing.

As the Commonwealth staggered toward its twilight, these new voices had already begun to claim their space within the literary tradition. When the Restoration came, it would find not only theatres reopening and Cavaliers returning, but women writers stepping boldly into the public sphere, their talents forged in the quiet fires of this shadowed age.

Now, as we turn toward the drama that survived without the stage, we shall see how the English imagination, denied its accustomed forms, refused to die but transformed itself into new and unexpected shapes.

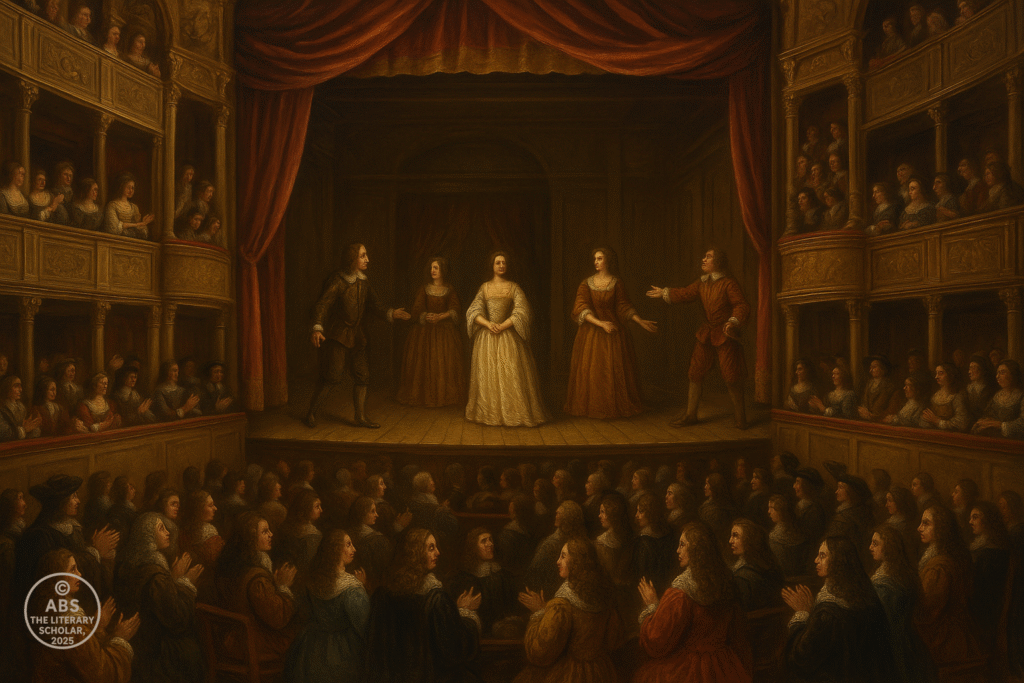

The Theatre Without a Stage

If the theatre is the mirror of a nation’s soul, then England, in the years of the Puritan Interregnum, gazed into a blank and shrouded glass. The Parliament’s decree of 1642, which had ordered all theatres closed, did more than silence the players, it attempted to sever the ancient bond between dramatic art and public life. Theatres that had once resounded with the living voices of Shakespeare, Marlowe, Jonson, and a host of lesser stars, now stood cold and empty, their stages dark, their balconies gathering dust beneath the high wooden beams.

Yet England’s love of drama, forged in centuries of storytelling and sharpened in the fires of the Renaissance, was not so easily extinguished. The public stage might be barred, but the private theatre of the mind remained sovereign. When drama could no longer be performed, it was read. When it could not fill the public ear, it spoke to the private heart.

Thus emerged a curious and potent form — Closet Drama, the play designed not for performance but for contemplation, to be read in solitude or in trusted circles, its power now residing not in voice and gesture, but in the inner theatre of the reader’s imagination.

In this silent age, closet drama became a vessel for philosophical reflection, political allegory, and personal lament. Its dialogues echoed with the tensions of a nation riven by war and ruled by saints. Through veiled language and classical guise, it addressed questions too dangerous for open discussion: the nature of tyranny, the price of freedom, the fate of the fallen.

One of the boldest contributors to this tradition was Sir William Davenant, a former court poet and playwright whose earlier life had been shaped by the splendid masques and elaborate productions of the Stuart court. With the stage now forbidden, Davenant turned to the page, crafting Gondibert, an epic verse drama that sought to marry the traditions of chivalric romance with the contemplative depth of philosophical dialogue.

Gondibert was no simple entertainment. It was a work designed to sustain the spirit of a fallen aristocratic culture, to preserve its values of honour, loyalty, and moral reflection, in an age that seemed bent upon their erasure. Davenant’s own preface declared his purpose clearly — the play was meant to be read, not acted. In this, he claimed a new space for drama, one beyond the reach of Puritan censors.

Even more profound was the contribution of John Milton, whose tragic drama Samson Agonistes, though published later, was conceived in these years of private darkness. Blind, politically embattled, yet still ablaze with intellectual fire, Milton turned to the ancient model of the Greek chorus to express a drama of internal struggle and ultimate defiance.

“Eyeless in Gaza, at the mill with slaves.”

These words, echoing through Samson’s tragic fate, resonated deeply with the state of England itself. Milton, like his Samson, had seen his grand vision of a godly republic shackled and perverted. His own blindness mirrored the moral blindness he perceived in the nation. Yet through this drama, he forged an enduring meditation on power, faith, and the resilience of the human spirit.

Elsewhere, too, in lesser-known works, the dramatic imagination persisted. Women writers, inspired by both classical models and personal experience, adopted the form to explore themes of virtue, friendship, and spiritual trial. Political dissenters encoded critiques of the regime in allegorical dialogues and moral fables. Even prose fiction absorbed the rhythms of dramatic dialogue, its pages alive with the tension of unseen performances.

Thus, though the physical theatre lay in ruins, the art of drama proved indestructible. England had carried its stage inward, into the mind and onto the printed page, where no ordinance could entirely silence it. In private chambers across the land, readers became their own audiences, the ancient pleasures of plot, character, and conflict sustained by the silent collaboration between writer and reader.

Ironically, the Puritan regime, in seeking to purify the nation of theatrical corruption, had ensured that drama would evolve, not vanish. Closet drama preserved the habit of reflection, the appetite for allegory, the taste for tragic grandeur that would soon find fresh expression when the theatres reopened.

And when that day came, when the curtain finally rose again upon a public stage, it would be these hidden legacies, nurtured in darkness, that would help rekindle the vibrant fire of English drama.

Now, with the passing of Cromwell and the faltering of the saints, the land stood poised for change. The Puritan grip was loosening, and England, weary of sermons and strife, looked once more toward the exiled son of its fallen king.

Twilight of the Saints — England Awaits a King

By the late 1650s, England was a land grown tired of its own revolution. The fierce idealism that had driven men to war and toppled a king had hardened into the stern routines of military rule and moral policing. The saints who had once thundered with purpose now presided over a nation restless beneath its grey mantle. The fires of Puritan certainty still burned in the pulpits, but in the hearts of the people, an older longing had begun to stir.

The death of Oliver Cromwell in September 1658 was both an ending and an opening. The man who had held the fragile Commonwealth together through sheer force of will had been laid to rest, his body buried with the honours of a king he had once helped destroy. His son, Richard Cromwell, inherited neither his father’s authority nor his iron resolve. The Protectorate began to falter.

The army, whose swords had once forged the republic, grew impatient and unruly. Parliament, fragmented by faction and fatigue, struggled to govern. In the taverns and marketplaces, in the corners of private gatherings, a forbidden name began to be spoken more freely — Charles Stuart. The son of the executed king, long exiled and watched by spies, was now seen not merely as the heir of a fallen dynasty, but as a possible balm for a weary land.

England, having endured the long years of Puritan restraint, hungered once more for the simple pleasures of life. Theatres, still officially closed, were remembered with fondness. Maypoles, once banned as pagan relics, became symbols of lost merriment. Christmas, stripped of its festivity, lived on in stubborn household traditions. The sermons that had replaced soliloquies began to ring hollow. The English soul, which no law could fully repress, yearned to laugh again, to sing, to celebrate.

The literary imagination mirrored this yearning. Poets whispered of spring returning, of the coming of a more generous age. Satirical tracts mocked the saints with growing boldness. Manuscript poems circulated that dared to hope for the restoration of a livelier, freer England.

Behind the scenes, political currents moved swiftly. General George Monck, marching south from Scotland, played the role of the cautious kingmaker. His forces steadied London as Parliament, sensing the tide, opened negotiations. Charles II, wiser than his father in the ways of statecraft and self-preservation, prepared to return — not as a conqueror, but as a symbol of reconciliation.

In May 1660, the monarchy was restored. England’s long Puritan experiment had ended not in another civil war, but in a collective sigh of exhaustion. The people welcomed their new king not merely out of loyalty, but out of a deep, human craving for joy, for colour, for life.

“A merry monarch, scandalous and poor,” as John Dryden would later write with a mixture of irony and relief, but a monarch nonetheless.

Theatres reopened in a burst of pent-up energy. Playhouses filled once more, the boards alive with voices that had been forced to the page. Actors returned, and for the first time, women appeared on the English stage, their presence a signal that the old order would not be entirely restored, but transformed.

The literary spirit of England, tested in chains and shadows, emerged tempered and enriched. Prose had gained a sharper edge, poetry a deeper inwardness, and drama a resilience born of exile. The pen had survived where the sword had failed.

As the Restoration dawned, England stood poised on the threshold of a new literary age — one that would blend the wit of the court with the wisdom forged in adversity. The saints had faded into history, but the voices they had sought to silence would now speak more freely, and more richly, than ever before.

And so, the scroll of the Puritan Interregnum draws to a close, its lessons etched in ink and memory. The curtain was ready to rise again, and England, with all her frailties and glories, would step once more into the light.

Chains Broken, Voices Remembered

The Puritan Interregnum stands in English literary history as a time not only of silence and censorship, but of remarkable resilience. An era when the axe fell upon a king, when the theatres fell dark, when the printed word was bound in chains, and yet the spirit of the pen refused to kneel.

The poets who mourned in exile, the playwrights who retreated to private pages, the women who dared to write where no stage would yet receive them, the polemicists who battled for the freedom of thought — each carried forward the literary flame through years when the saints would have smothered it.

England’s literature did not wither, it transformed. Its voice grew quieter but deeper, its forms subtler but more enduring. From pamphlet to closet drama, from sonnet to secret song, the nation’s imagination adapted to its age of chains. And in doing so, it preserved not only the art of language, but the idea that no regime, however righteous it believes itself to be, can own the soul of a people or silence the imagination of a land.

When the Restoration came, it found an England whose stage had been waiting behind closed curtains, whose poets had written in the margins, whose women had claimed new literary spaces, and whose greatest blind poet, John Milton, had already forged a work of timeless power in the darkness of his sightless vision.

From shadows, literature had learned to speak anew.

From chains, it had learned the shape of freedom.

And as the next age of English letters would soon unfold — bold, dazzling, unrepentantly public once more — it would do so with the hard-won lessons of an era when words had walked softly, but carried unbroken truths.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Professor.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance