When poetry abandoned the heart for the head, and drama bowed before decorum.

From The Professor's Desk

The theatres had reopened, the crowds had returned, and London once again hummed with song and laughter. Yet beneath this glittering surface, English literature had changed irreversibly. The Puritan age had stripped poetry of its excesses, taught writers caution, and turned the pen toward satire and moral reflection. The Restoration, far from restoring the carefree spirit of Elizabethan art, ushered in a new literary regime — one dominated by intellect, form, and fashion.

Where Shakespeare’s players had once spoken to the masses, now the poets spoke to each other, in polished couplets and epigrammatic wit. The golden torrent of Elizabethan imagination had slowed to an elegant trickle, measured and controlled. Poetry had become a game of minds, not of souls.

Thus began the Neoclassical Age — an era that revered ancient models, prized reason above passion, and fashioned verse into a courtly conversation for the few.

The age that followed England’s Puritan interregnum did not so much restore the old world as invent a new one. The theatres reopened, the court glittered once more, and poets and playwrights found their public voices again. Yet they did not, and could not, simply pick up where Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Jonson had left off. The world had changed.

The Neoclassical Age, as posterity would name it, was less a rebirth of the Renaissance spirit than a deliberate turning toward the ideals of ancient Greece and Rome — a world of order, reason, form, and restraint. It was called Neoclassical because its writers and thinkers consciously sought to revive and emulate the classical standards of art and literature, not the wild, unbounded imagination of the Elizabethans.

The forces that drove this transformation were many. Scientific discoveries, led by figures such as Newton, had shifted the intellectual climate toward reason and observation. Exploration had expanded the world, but also demystified it, reducing ancient wonders to measurable phenomena. The Puritan regime had taught the dangers of emotional excess, both in politics and in art. In this new atmosphere, the grandeur of Elizabethan poetry seemed extravagant, its passions naive.

The new poets, heirs to both Bacon’s sharp prose and Donne’s metaphysical wit, turned away from the lush sensuality of Spenser, the raw drama of Shakespeare, the heroic romances of the past. Instead, they pursued precision, balance, decorum — and above all, wit. Poetry became a conversation among the educated, a game of intellect, where cleverness triumphed over feeling.

As Sir Francis Bacon had declared, knowledge itself was power. In literature, this power expressed itself through clarity and argument, not through mysticism or wild beauty. John Donne, in the late Elizabethan and Jacobean age, had already begun this transformation. His metaphysical conceits and epigrammatic style signaled a shift from the emotional to the intellectual, from the pastoral to the urban.

But it was the Puritan period, with its forced restraint and suppression of theatrical spectacle, that hardened this trend. When the Restoration brought Charles II back to the throne, it also unleashed a flood of repressed energies — but now these energies flowed through the channels of satire, mock-heroic verse, and polished couplets.

Wit became the new currency of poetry.

The Restoration poets, and their successors in the Augustan Age, spoke not to the broad public, but to their fellow wits, their patrons, their royal audiences. The common people were largely left behind. Where Shakespeare had written for both court and commoner, the Neoclassical poets wrote for the salons, the coffeehouses, the court. Poetry became a mark of social distinction, not a common art.

“True wit is nature to advantage dressed,

What oft was thought, but ne’er so well expressed.”

— Alexander Pope

This famous couplet from Pope perfectly captures the spirit of the age. The poet’s task was not to invent new truths, but to express old ones with elegance and precision. Art became a mirror held up to nature, polished to reflect not its wildness, but its order.

In this age of learning, poetry became the preserve of the educated, the cultivated. The common heart was no longer its audience, nor its concern. The theatres, though reopened, catered to a new taste — the Comedy of Manners, with its sharp social satire, its cynicism, its elegant immorality.

Thus the Neoclassical Age, for all its brilliance, marked a profound narrowing of the literary imagination. Its poets were no less talented than their Elizabethan forebears, but they addressed a smaller world — one of wits, courtiers, and gentlemen of leisure. The humble and the passionate were excluded. Poetry became an art of surfaces, of style over substance, of the head over the heart.

Yet within these constraints, great artistry flourished. The heroic couplet reached perfection, satire achieved new heights, and English prose matured into a powerful instrument of thought and persuasion.

It was an age that mastered form, but lost feeling. And from this paradox, the literary history of the Neoclassical period would unfold.

Now, as we open this scroll, we turn first to the Restoration, where Dryden stood at the centre of England’s new cultural stage, and where the first voices of the Neoclassical Age found their public expression.

Restoration (Age of Dryden)

The King Returns, and So Does the Stage

The bells of London rang with a joy no sermon could still. After years of grey Puritan restraint, the city’s streets surged with colour and sound. Flags flew, shopkeepers dressed their windows in bright silks, and the long-silent taverns overflowed with celebration. Charles II had returned, the king restored, and with him, the soul of England seemed ready to breathe again.

Yet this was no simple return to the past. The years of Civil War and Commonwealth had carved deep wounds into the nation’s psyche. The theatres that had once echoed with Shakespeare’s sonnets and Jonson’s biting wit had stood dark for nearly two decades. A generation had grown to manhood who had never seen a public play. The very art of drama seemed a relic of a lost world.

Now, in May 1660, as the monarchy reclaimed its throne, the theatre would rise again — but not untouched by the storms that had passed over England.

The Restoration of Charles II was as much a cultural event as a political one. The court that gathered around the returning monarch was eager to distance itself from the dour saints who had ruled in his absence. Pleasure, wit, and spectacle became the new currency of power. The king himself, seasoned by exile in the more relaxed courts of France, brought with him a taste for elegance and licence.

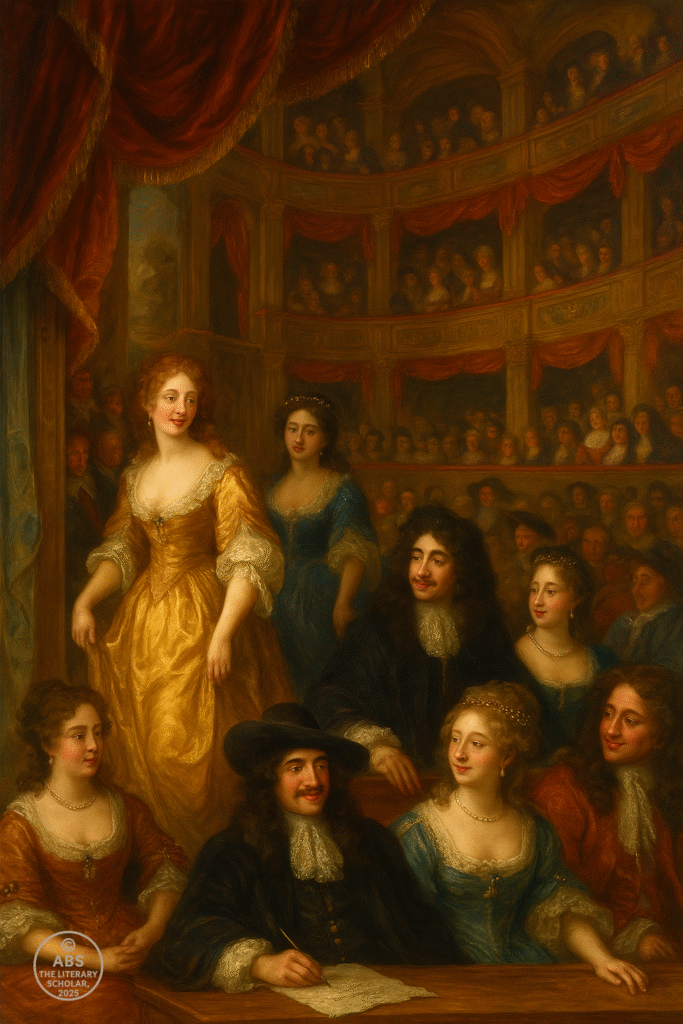

The stage, long silenced, became the perfect symbol of this cultural revival. The theatres reopened with royal approval. The King’s Company and The Duke’s Company were granted patents to perform, and the public thronged to see what they had so long been denied.

Yet the theatre they encountered was no mere revival of Elizabethan grandeur. The Restoration stage spoke a new language — urbane, witty, often scandalous, designed for a court that valued cleverness over wisdom, style over sincerity. The popular taste now favoured the Comedy of Manners, where sparkling dialogue and elaborate plots masked a deeper cynicism about love, honour, and society.

At the heart of this transformation stood John Dryden, the towering literary figure of the Restoration. Though he had begun his career under the Commonwealth, Dryden quickly adapted to the new regime. His Astraea Redux, a celebratory poem on Charles II’s return, signalled both his personal loyalty and his literary ambition:

“An horrid stillness first invades the ear,

And in that silence we a tempest fear.”

In these lines, Dryden captured the uneasy joy of a nation emerging from the long silence of Puritan rule. The Restoration, for all its glitter, carried the weight of recent memory — the scaffold of Charles I, the sermons of Cromwell’s saints, the darkened stages.

Now, literature would serve a new court, a new king, a new age.

Dryden’s rise was swift. By 1668, he was named Poet Laureate, the official voice of the monarchy. His verse dramas and heroic plays dominated the stage. Though critics would later deride the artificiality of heroic drama, in its moment it answered a national hunger for spectacle and grandeur.

The theatre, once a mirror to all England, now reflected primarily its elite. Where Shakespeare had written for groundlings and courtiers alike, the Restoration playwrights addressed a narrower audience — the fashionable, the educated, the morally flexible. The common people, though welcome in the pit, found little that spoke to their lives or hopes.

Yet for the court and the capital’s wits, the stage became a glittering playground. The actresses, now appearing legally on stage for the first time in English history, brought a new allure to the theatre. Figures like Nell Gwyn, mistress to the king and beloved of the public, embodied the Restoration’s embrace of pleasure, performance, and wit.

Meanwhile, playwrights experimented boldly with form and content. The Comedy of Manners crystallised into a genre marked by:

social satire,

sexual intrigue,

verbal brilliance,

and a cultivated world-weariness.

The Restoration audience, scarred by civil strife and religious repression, now sought diversion rather than moral instruction. In the words of the playwright George Etherege:

“Let us be merry now, and wisely too;

Who knows how soon we must the game give o’er?”

Thus, as the curtain rose on a new age, English literature had been subtly but profoundly altered. The grandeur of Elizabethan tragedy had given way to the glitter of courtly comedy. The moral weight of Shakespeare and Milton was displaced by the sparkling levity of Congreve and Wycherley.

In this world, John Dryden stood as both bridge and architect — a poet who honoured the classical past, mastered the Restoration present, and prepared the ground for the Augustan future.

The stage was alive once more. The players had returned. But the play had changed.

As we turn now to Dryden’s career, we will see how one man’s pen shaped the literary voice of the Restoration, and how the values of wit, form, and reason came to define a generation.

Dryden: Voice of a Restored Nation

When the dust of civil war had settled and the theatres of London once again welcomed their expectant audiences, one figure would soon rise to dominate the new literary stage — John Dryden. If Charles II embodied the political restoration of monarchy, Dryden embodied the literary restoration of order and elegance. In his hands, English poetry and drama would be reshaped to suit the sensibilities of a changed nation.

Born in 1631, Dryden had been formed by the intellectual rigor of the Puritan era and the classical ideals of the Renaissance. His education at Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge steeped him in the virtues of classical form, rhetoric, and moral clarity. Yet Dryden was no dogmatic thinker. His great gift lay in his ability to adapt, to read the temper of the times, and to craft verse that both reflected and shaped the cultural mood.

Dryden’s public literary career began under the shadow of the Commonwealth. His first significant poem, Heroic Stanzas, was written on the death of Oliver Cromwell. Yet with the Restoration, Dryden’s literary allegiance shifted swiftly and pragmatically. In 1660, his Astraea Redux welcomed the return of Charles II, signalling both his personal loyalty and his literary ambition.

“But heaven has now dispell’d those clouds again,

And makes one day repay the years of pain.”

These lines not only captured the public relief at the Restoration but also foreshadowed the emerging tone of Restoration literature — a tone of measured optimism, seeking order after chaos, and elegance after austerity.

In the newly reopened theatres, Dryden proved himself a master of heroic drama — a genre that, while now often dismissed as artificial, fulfilled a vital cultural role in its moment. England, weary of political turmoil and moral sermonising, craved spectacle and grandeur. Dryden’s verse dramas, such as The Indian Queen and The Conquest of Granada, provided precisely this. They offered audiences a world of heroic figures, grand passions, and elevated rhetoric, all framed within the disciplined structure of rhymed couplets.

It was in the heroic couplet that Dryden found his true instrument. He perfected its balance, rhythm, and expressive potential, forging a style that would become the dominant poetic mode of the next half-century. His couplets were not mere mechanical rhymes; they carried argument, irony, and subtle variation, elevating the form beyond the confines of Restoration drama.

Yet Dryden’s greatest literary achievements would come not on the stage, but in the realm of satire and public verse. As the political landscape of Restoration England grew ever more volatile, Dryden emerged as its chief poetic commentator. His Absalom and Achitophel (1681), a brilliant political allegory on the Exclusion Crisis, remains a masterpiece of controlled invective and wit.

“Great wits are sure to madness near allied,

And thin partitions do their bounds divide.”

In this single couplet, Dryden distilled the precarious brilliance of political ambition — a line that has outlived the specific controversies of its age to become a timeless reflection on human folly.

As Poet Laureate and Historiographer Royal, Dryden held official positions that made him the literary voice of the monarchy. Yet his genius lay in the ability to speak beyond the merely official. In works such as Mac Flecknoe, he wielded satire as both sword and scalpel, exposing literary pretension and political absurdity with unmatched grace and precision.

“Shadwell alone my perfect image bears,

Mature in dullness from his tender years.”

In this mock-heroic poem, Dryden skewered the mediocre playwright Thomas Shadwell, turning personal rivalry into a public spectacle of poetic brilliance. Through such works, Dryden defined the tone of Restoration wit — a tone that was both urbane and ruthless, polished yet piercing.

Beyond satire, Dryden contributed significantly to literary criticism, a field still in its infancy. His Essay of Dramatic Poesy (1668) remains a foundational text, articulating principles of literary decorum, the unities of drama, and the value of classical restraint. In this essay, Dryden defended the legitimacy of English drama while acknowledging its debts to classical models — a quintessentially Neoclassical perspective, balancing reverence for the past with adaptation to the present.

As the Restoration progressed, Dryden’s literary voice continued to evolve. His later works, such as the translation of Virgil and the Fables Ancient and Modern, displayed a mature mastery of narrative verse and a deepening philosophical reflection. Even as younger poets like Pope would soon rise to prominence, Dryden’s influence remained paramount.

John Dryden was more than the laureate of his age; he was its architect. Through his verse, drama, satire, and criticism, he shaped the literary values that would define the Augustan Age. He demonstrated that wit need not sacrifice wisdom, that form could serve substance, and that English poetry could speak with a voice as disciplined as it was vibrant.

As we move next to the realm of Restoration Comedy, we will see how the theatre reflected the same spirit — dazzling, cynical, brilliant — that Dryden’s pen had so powerfully embodied.

The Glittering Vice: Restoration Comedy

If John Dryden was the moral architect of Restoration verse, then the Restoration stage was the glittering mirror of its manners — or its lack thereof. Nowhere is the cultural shift from Elizabethan drama to Neoclassical wit more starkly visible than in the evolution of English comedy after the Restoration. The rich tapestry of Shakespeare’s comedies — full of lyricism, rustic humour, and universal humanity — gave way to a new form: the Comedy of Manners, dazzling, cynical, and unapologetically elite.

Theatre, long silenced under Puritan rule, reopened in 1660 with eager royal support. Yet the cultural climate had changed profoundly. The new audience that filled the playhouses of London was not the broad cross-section that once cheered for Falstaff or wept for Desdemona. The pit still held the rowdy and the curious, but the boxes gleamed with courtiers, wits, and mistresses — a sophisticated elite for whom wit and style mattered more than moral depth.

It was for this audience that Restoration Comedy was crafted. The dramas of this age dispensed with the pastoral and the romantic, replacing them with urban sophistication, sexual intrigue, and merciless satire of social pretension. The Restoration stage became a space where the hypocrisies of the court and the foibles of fashionable society were exposed, and where cleverness was prized above virtue.

William Wycherley, one of the era’s boldest voices, captured this spirit perfectly in The Country Wife — a play notorious for its sexual frankness and its unflinching portrayal of male libertinism and female duplicity. The plot centres around Horner, who feigns impotence in order to seduce the wives of unsuspecting husbands. Such themes would have been unthinkable in the age of Shakespeare; in the Restoration theatre, they were greeted with delighted laughter.

“Women and wine, game and deceit,

Make the full business of the year complete.”

— The Country Wife

William Congreve, whose plays represent the peak of Restoration Comedy’s literary refinement, brought a sharper, more elegant wit to the genre. His masterpiece, The Way of the World, is less openly licentious than Wycherley’s work, yet even more pitiless in its exposure of social games and emotional insincerity. Congreve’s dialogue sparkles with epigrammatic brilliance, each exchange a duel of intellects.

“Say what you will, ’tis better to be left than never to have been loved.”

— The Way of the World

George Etherege, with plays such as The Man of Mode, further codified the genre. His characters — fashionable rakes, witty ladies, foolish old men — moved through a world where appearances mattered most, and where marriage was a transaction rather than a union of souls.

What unites these comedies is not their plot machinery — often recycled from earlier French or Italian sources — but their tone. The Restoration stage was the playground of the urban elite, a space where the clever demonstrated their mastery of the social game, and where the moral earnestness of earlier drama was replaced by sophisticated cynicism.

Women, too, played a new and vital role in this theatrical world. For the first time, actresses appeared legally on the English stage, bringing a new sexual frankness and realism to female roles. Nell Gwyn, actress and royal mistress, became a symbol of this new era — a figure who embodied both the liberation and the objectification of women in Restoration theatre.

Yet this glittering vice was not without its critics. Jeremy Collier’s A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage (1698) attacked the Restoration dramatists for their obscenity and their corrosive moral influence. Though Collier’s puritanical zeal found little favour at court, it did signal a broader cultural unease. By the turn of the century, the Restoration stage’s license and libertinism were beginning to give way to the more restrained moral climate of the Augustan Age.

Still, the legacy of Restoration Comedy is profound. It marked the final severance of English drama from the populist roots of Elizabethan theatre. No longer a shared national art, the stage had become a mirror for the few, a space of dazzling language and brittle sophistication. The common people, once the lifeblood of the theatre, now stood outside its glittering circle.

As we turn next to the courtier poets, we will see how this same spirit of urbane wit and social exclusivity permeated not only the drama but the poetry of the Restoration elite.

The Age of Wit: The Courtier Poets

If the Restoration theatre dazzled its elite audiences with verbal brilliance and social satire, the poets of Charles II’s court pursued the same art of wit and polished expression in verse. In this world, poetry was no longer the voice of a nation’s soul but a game of intellectual display — a medium through which courtiers mocked, flirted, and sparred for social dominance.

The courtier poets of the Restoration were, in many cases, less professional writers than aristocratic amateurs, whose verse emerged from the salons and coffeehouses of London. Their works were not intended for the broad public but for a circle of fellow wits, where the sharpness of the couplet and the sting of the epigram mattered more than any universal truth or emotional depth.

At the heart of this culture stood John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester — a poet whose brilliance was matched only by his self-destructive wit. Rochester’s verse embodies the Restoration spirit in its purest, most corrosive form: urbane, cynical, laced with sexual frankness and scorn for human folly.

In his famous A Satire Against Reason and Mankind, Rochester mocks the pretensions of human intellect and moral superiority:

“Reason, an ignis fatuus of the mind,

Which leaves the light of Nature, Sense, behind.”

This is not the hopeful humanism of the Renaissance, nor the moral gravity of Milton. It is wit wielded as a weapon, cutting through hypocrisy with a blade honed by experience and disillusionment.

Rochester’s personal life mirrored his verse. A court favourite and a notorious rake, he lived with a reckless abandon that found its counterpart in his poetry. Yet for all its licentiousness, Rochester’s verse is marked by an unflinching honesty, a refusal to dress life’s darker truths in the finery of poetic convention.

Around Rochester gathered a circle of courtly versifiers, whose works contributed to the Restoration’s literary atmosphere. Figures such as Charles Sackville, Earl of Dorset, and Sir Charles Sedley composed verse that was by turns erotic, satirical, and elegantly trivial. These poets reveled in the artifice of form, crafting poems where cleverness mattered more than sincerity, where the play of language eclipsed the play of feeling.

“In love’s soft war, if you would conquest gain,

Let dulness fail, let sparkling wit remain.”

— Anonymous Restoration couplet

Even those poets of greater ambition, such as John Oldham, adopted the Restoration tone of urbane disenchantment. Oldham’s satires, though morally earnest, are framed in the heroic couplets and rhetorical style that Dryden had perfected.

This Age of Wit was, in essence, a reaction against the moral earnestness and emotional depth of earlier poetry. The Puritan suppression of the arts had taught writers caution; the Restoration response was not a return to unguarded feeling but an embrace of controlled brilliance. In this world, to feel deeply was to risk vulgarity; to express cleverly was to achieve social triumph.

Yet this narrowing of poetry’s purpose came at a cost. The Restoration poets spoke largely to each other, their language increasingly detached from the broader public. The rich lyricism of the Elizabethans, the metaphysical daring of Donne and Herbert, had given way to a poetry of surface charm and intellectual display.

As we prepare to enter the Augustan Age, we will see how this Restoration culture of wit, form, and classical imitation would crystallize under the pen of Alexander Pope and his contemporaries. The stage was set not only for a further perfection of form but for an even greater alienation of poetry from the common heart.

Poetry had become a conversation among the few, and the Age of Wit had crowned its kings.

Legacy of the Restoration, Prelude to the Augustans

As the 17th century drew to its close, the Restoration had done more than revive English theatre and poetry — it had reshaped the very idea of what literature should be. From the ruins of civil war and Puritan restraint, the Neoclassical spirit had emerged triumphant, bringing with it new ideals of order, decorum, and intellectual elegance.

Yet the Restoration’s literary culture was a paradox. It had reopened the stage, but narrowed its moral scope. It had revived poetry, but transformed it into a language of wit for an educated elite. The Restoration writers had not sought to recover the lost grandeur of Elizabethan drama or the spiritual depth of metaphysical poetry; instead, they had fashioned a new literature, one that mirrored the tastes of a courtly and urban society.

John Dryden, more than any other figure, had embodied this transformation. His heroic couplets, his masterful satires, and his critical essays provided the stylistic and intellectual foundation upon which the next generation would build. Through Dryden’s example, the Restoration bequeathed to English letters a commitment to form, clarity, and rhetorical power that would define the coming Augustan Age.

At the same time, the Restoration had left unresolved tensions in the literary culture. The exuberant cynicism of Restoration Comedy had provoked moral backlash. The courtier poets’ exclusive wit had alienated broader audiences. A growing middle class of readers, increasingly literate and morally earnest, sought a literature that could speak to reason and virtue, not merely to fashionable vice.

It was in this atmosphere of transition and tension that the seeds of the Augustan Age were sown. The literary salons and coffeehouses of London became the new arenas of intellectual exchange, where poets, essayists, and critics debated not only matters of style but also the moral purpose of literature.

The heroic couplet, honed by Dryden, would reach new heights in the hands of Alexander Pope. The sharp satire of Restoration drama would find more enduring expression in the prose of Jonathan Swift and the essays of Addison and Steele. The Restoration’s obsession with wit and polish would be tempered by a new Augustan ideal of order, balance, and civic virtue.

Yet even as the Restoration passed, its influence remained profound. The values it had established — a reverence for classical models, a dedication to stylistic precision, a taste for satire and intellectual play — would dominate English literature for much of the 18th century.

As we now turn to the Augustan Age, we will see how Pope, Swift, and their contemporaries built upon the Restoration legacy, refining its forms and expanding its reach. The Neoclassical ideal would come into full flower, as poetry and prose alike sought to balance reason and wit, morality and art.

The curtain had risen in 1660. By the dawn of the 18th century, the play had become a polished performance, its language elegant, its audience discerning, its vision increasingly focused on the life of the mind.

The Restoration: Wit Crowned, Hearts Forgotten

The Restoration had opened the theatre doors and summoned the poets back to their desks, but it had not restored the old soul of English literature. The golden fire of the Elizabethans had dimmed, replaced by a colder brilliance. The Restoration gave England wit, form, and urbane polish, but it narrowed the audience and diminished the emotional depth that once flowed through stage and page.

John Dryden stood as the master of this new world — a poet who could command heroic couplets as deftly as he wielded political satire. Restoration Comedy glittered with elegance and vice, its courtiers and rakes outshining the humble humanity of the common stage. In the coffeehouses, poets and wits played their games of intellect, turning verse and prose into weapons of wit, their targets drawn from the foibles of fashion and the follies of men.

Yet beneath the laughter and sparkle, a deeper truth remained. Literature had become the province of the few. The court and the city’s elite shaped its language and its concerns, while the broader soul of the nation stood outside the glow of candlelit theatres and fashionable salons.

Now, as we close this part of the scroll, the stage is set for the next great evolution. The Augustan Age will inherit the Restoration’s commitment to form, but it will seek to reclaim something more — an order of reason, a moral clarity, and a literary purpose that reaches beyond mere brilliance.

The Restoration had crowned wit as king. The Augustans would soon ask whether truth and virtue might not have a place beside it.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance