Poetic Visions, Religious Voices, and The Drama of the Middle English Mind in Middle English poetry and drama

From The Professor's Desk

Beyond Chaucer’s towering influence, the later Middle English period witnessed an extraordinary flowering of literary voices — each contributing in distinctive ways to the evolution of English thought and expression. This was an age when knightly ideals, moral allegory, religious mysticism, and popular drama converged to produce works of remarkable variety and depth.

In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the ideals of chivalry and virtue are tested in a narrative of both physical and moral courage. In Piers Plowman, William Langland constructs an ambitious allegorical vision of spiritual striving and social justice. The voice of John Gower offers a structured poetic meditation on love and ethics, while Julian of Norwich brings profound theological insight in one of the most original mystical texts in English prose.

The writings of John Lydgate and Thomas Hoccleve extend the Chaucerian legacy into the fifteenth century, exploring themes of classical history, princely instruction, and mortality. Margery Kempe, through her unique Book, offers an extraordinary autobiographical account of spiritual experience — the first of its kind in English. Finally, the Mystery Plays of York and Wakefield brought religious drama into the public sphere, blending doctrinal teaching with the earthy vitality of popular performance.

This part of our journey through the Middle English period reveals the diversity of the era’s literary imagination — an imagination shaped by faith, by social change, and by a deepening sense of English identity. We now turn to these voices, each distinct, each contributing to the rich tapestry of Middle English literature.

“Sir Gawain and the Green Knight”

“Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” is a medieval chivalric romance that tells the story of Sir Gawain, a knight of King Arthur’s Round Table. The poem is known for its blend of adventure, romance, and moral complexity.

Part 1: The Green Knight’s Challenge

The story begins with a Christmas feast at Camelot, where King Arthur and his knights are celebrating. Suddenly, a mysterious Green Knight enters the hall riding a green horse. The Green Knight challenges the knights to a game: any knight who dares strike him with his own axe may keep the axe, but the knight must agree to receive a return blow in exactly one year and one day.

The young Sir Gawain accepts the challenge and beheads the Green Knight with one blow. However, to everyone’s surprise, the Green Knight picks up his head and reminds Gawain of his promise to receive the return blow in a year and a day.

Part 2: Gawain’s Quest

As the year passes, Gawain prepares for his journey to find the Green Knight’s Green Chapel to fulfill his end of the bargain. Along the way, he faces various challenges and adventures, including battling monsters and resisting temptations.

Gawain eventually reaches a castle, where he is warmly welcomed by Lord Bertilak and his wife, Lady Bertilak. Lady Bertilak tempts Gawain with her advances, testing his virtue. She offers him a green girdle that she claims will protect him from harm. Gawain, despite his resistance, accepts the girdle.

Part 3: The Exchange of Blows

On New Year’s Day, Gawain sets out for the Green Chapel to meet the Green Knight. The Green Knight takes three swings at Gawain with his axe, but each time, he stops before striking to test Gawain’s courage. Gawain flinches at the third swing, breaking his promise, but the Green Knight merely nicks his neck, sparing his life.

The Green Knight reveals his identity as Lord Bertilak and explains that the challenges Gawain faced were set up by Morgan le Fay, Arthur’s half-sister, to test Gawain’s virtue and Arthur’s court. Despite Gawain’s minor failing, he is still praised for his overall courage and integrity.

Themes in “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight”:

Chivalry and Honor: The poem explores the ideals of chivalry, honor, and integrity that knights are expected to uphold.

Testing of Virtue: Gawain’s journey tests his moral character and exposes the complexities of human behavior.

Nature and Civilization: The contrast between the natural world and the courtly civilization symbolizes the tension between primal instincts and societal norms.

Fidelity and Loyalty: Gawain’s loyalty to the code of chivalry and his honor are central themes as he faces moral dilemmas.

Symbolism: Elements like the green color, the girdle, and the axe hold symbolic significance throughout the poem.

“Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” is a tale of bravery, moral challenges, and the intricacies of human nature. It offers insights into the ideals of knighthood, the nature of honor, and the internal conflicts individuals face when tested.

Some beautiful quotes from other Middle English poets:

“He hath made us and shall make us, in his own mercy, without beginning and end.” – Julian of Norwich

Julian’s words express the divine nature of God’s creation and everlasting love.

“Ever musing I delight to tread the Paths of honour and the Myrtle Grove.” – John Milton (not Middle English, but Early Modern English)

While not Middle English, this quote from John Milton reflects the poetic spirit of his time, reminiscent of the Middle English poets.

“A thousand years are like an evening gone, a watch in the night.” – Pearl Poet, “Pearl”

This line captures the temporal nature of human existence and the fleeting nature of time.

“The sun shall lose his brightness, the moon her light, the sea its weight and heaviness and flood and all shall fail.” – Pearl Poet, “Pearl”

These words evoke a sense of cosmic upheaval and impermanence.

“In every gleam of light, and every bough, and every bird that sings, there is given a sign that God is in Heaven.” – Pearl Poet, “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight”

This quote reflects the Pearl Poet’s spiritual sensibility, finding divine presence in nature.

“Blessed be God that I have found Christ.” – Julian of Norwich

Julian’s words express her profound gratitude for her spiritual experiences.

“So is us leove folke, in oure Lordes pese.” – “The Owl and the Nightingale”

Translated: “So may we dear people, in our Lord’s peace.” This line expresses a desire for peace and unity.

“My sweet nightingale, wale and won.” – “The Owl and the Nightingale”

This phrase, filled with alliteration, captures the playful tone of this debate poem.

“The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne.” – Chaucer, “Parliament of Fowls” (also mentioned previously)

This line, often attributed to Chaucer, emphasizes the challenges of learning within the brevity of life.

“O little book, thou art so unconning; / How darest thou put thyself in prees for drede?” – John Lydgate, “The Complaint of the Black Knight”

This self-reflective verse expresses humility and trepidation about sharing one’s work.

William Langland

William Langland was a 14th-century English poet best known for his work “Piers Plowman.” Not much is known about his life, including his exact birth and death dates. He is believed to have been born around 1330 and to have lived in the West Midlands region of England. Langland’s work suggests that he had an intimate understanding of the social and religious issues of his time.

Piers Plowman

“Piers Plowman” is a Middle English alliterative poem that presents a vision of a quest for true Christian life and salvation. The poem is written in a series of interconnected allegorical dream visions and is considered one of the most significant works of Middle English literature. It reflects the social, religious, and philosophical concerns of Langland’s time.

Structure:

The poem exists in several versions and is quite lengthy. It is written in a series of sections called passus (Latin for “step” or “section”). The narrative is framed by the narrator’s dreams and visions.

Summary:

The poem follows the narrator, a “fair field-full of folk,” on a spiritual journey to seek Truth. The narrator falls asleep on a “fair hill,” and in his dream, he sees a “fair field full of folk” representing various aspects of society and human nature. The poem is rich in allegory and symbolism.

The central figure of the poem is Piers Plowman, a humble and allegorical everyman figure who represents the ideal Christian life. Piers Plowman’s name suggests his connection to manual labor and the common people. Throughout the poem, the narrator encounters various allegorical figures, such as Lady Holy Church, Piers’s wife, and other personifications.

The poem explores themes of social injustice, corruption, and the search for spiritual truth. The narrator witnesses the flaws and hypocrisy of various classes and institutions, including the church and the nobility. He learns about the importance of humility, charity, and the pursuit of genuine faith.

“Piers Plowman” is written in a complex and alliterative style, employing vivid imagery and allegorical characters. The poem consists of a series of visions, conversations, and allegorical representations that depict the narrator’s spiritual and moral journey.

The character of Piers Plowman embodies the Christian virtues of humility, patience, and charity. He represents the ideal Christian life and becomes a guide for the narrator as he navigates the challenges of the world. The poem also addresses the concepts of free will, salvation, and the role of grace in the context of medieval Christianity.

“Piers Plowman” is not only a moral and religious allegory but also a reflection of the social and political issues of Langland’s time. It offers a critique of the corruption within the Church, the inequalities of society, and the challenges faced by ordinary people seeking spiritual fulfillment.

Overall, “Piers Plowman” is a profound and complex work that provides valuable insights into the spiritual, social, and intellectual concerns of the 14th century.

John Gower

Life of John Gower (c. 1330-1408):was a 14th-century English poet and contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer. He was born around 1330 and came from a prosperous family with connections to the Kentish gentry. Gower received a good education and had strong ties to the English court. He was known for his knowledge of law and his interest in literature.

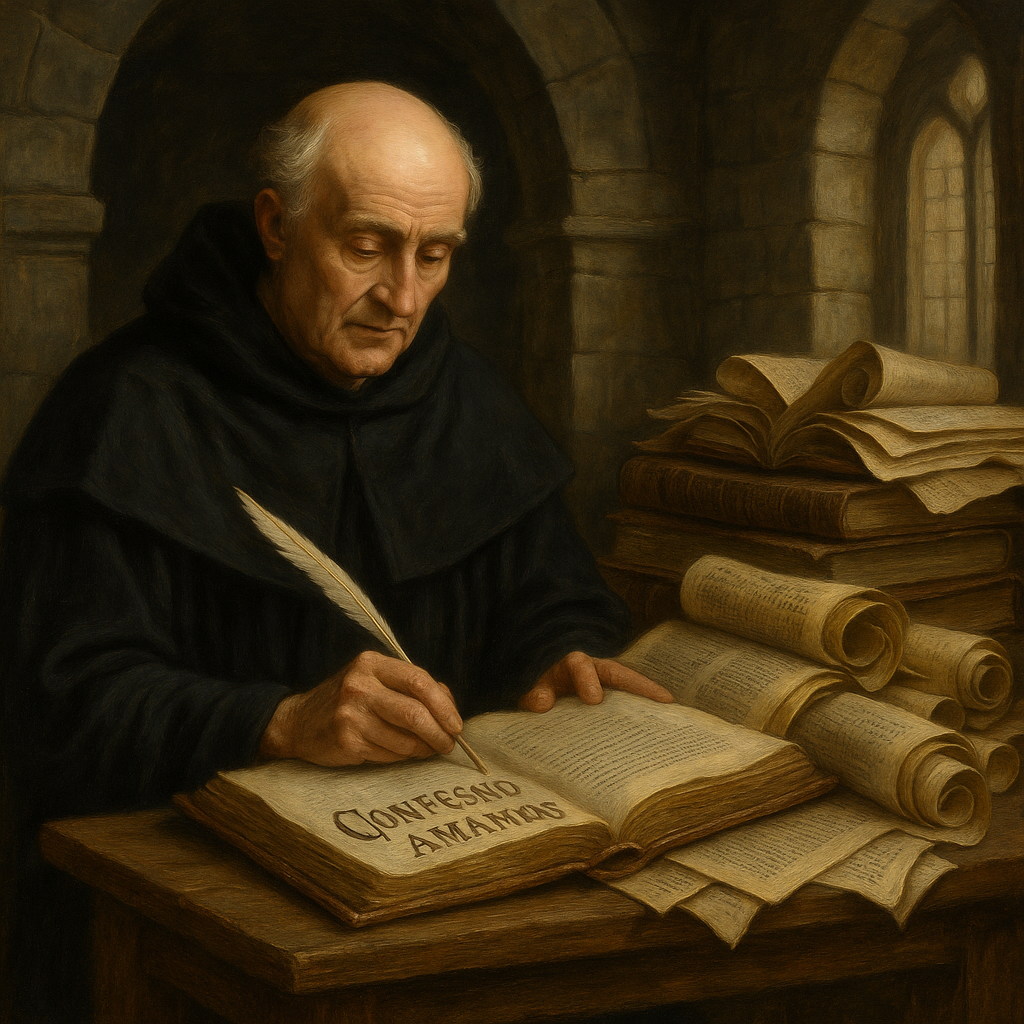

Gower’s most significant work is “Confessio Amantis,” which translates to “The Lover’s Confession.” This work is a substantial English poem written in the form of a dialogue between a lover and a priest.

“Confessio Amantis” (The Lover’s Confession):

“Confessio Amantis” is a major work of Middle English literature that explores the themes of love, ethics, and moral lessons. The poem is presented as a collection of stories and exempla (moral anecdotes) told by the lover to the priest. These stories cover a wide range of topics, including love, power, virtue, and the consequences of sinful behavior.

Structure:

The poem is divided into eight books, each of which is presented as a conversation between the lover and the priest. The lover confesses his sins and seeks moral guidance, and the priest responds by sharing stories that illustrate the points he wishes to make.

The lover’s confession provides the framework for the poem’s structure. He confesses his sins of lust to the priest and seeks advice on how to overcome his desires. The priest responds by telling stories from various historical and mythological sources. Each story addresses a specific moral issue or ethical dilemma, providing the lover with guidance on how to lead a virtuous life.

“Confessio Amantis” covers a wide range of subjects, including love, politics, theology, and human behavior. Gower draws on a diverse range of sources, including classical mythology, history, and medieval literature. The stories are often framed within a moral context, highlighting the consequences of sinful behavior and the importance of living according to ethical principles.

The characters and narratives in “Confessio Amantis” are allegorical and represent different aspects of human nature. The work is not only a collection of tales but also a reflective exploration of the complexities of human behavior and the moral choices individuals make.

Gower’s writing style is characterized by his use of rhyme royal, a seven-line stanza with a consistent rhyme scheme, and his ability to craft engaging and didactic narratives. His work demonstrates his deep understanding of medieval literature, classical knowledge, and moral philosophy.

“Confessio Amantis” is not only a literary masterpiece but also a reflection of Gower’s own moral and ethical beliefs. The poem offers readers insights into the moral values and concerns of the 14th century, making it a valuable contribution to Middle English literature.

John Gower earned the epithet “Moral Gower” due to his reputation as a poet who focused on moral and ethical themes in his works. The title reflects his emphasis on imparting moral lessons and ethical guidance through his poetry, particularly in his major work “Confessio Amantis” (The Lover’s Confession).

Gower’s “Confessio Amantis” is a substantial poem that consists of a dialogue between a lover and a priest, with the lover seeking moral advice and confessing his sins. The priest responds by sharing a wide range of stories and exempla that illustrate various moral and ethical points. These stories cover topics such as love, virtue, power, and the consequences of sinful behavior. Gower uses these narratives to offer readers guidance on leading virtuous lives and making ethical choices.

Given the prominent role of moral and ethical teachings in Gower’s poetry, he became known as “Moral Gower.” This title highlights his commitment to using literature as a vehicle for instructing readers in matters of morality and virtue. Gower’s focus on ethical themes was in line with the broader medieval tradition of didactic literature, which aimed to educate and edify readers through storytelling.

Overall, “Moral Gower” underscores John Gower’s dedication to crafting poetry that not only entertained but also enriched the reader’s understanding of moral principles and the complexities of human behavior.

Julian of Norwich

Julian of Norwich (c. 1342-1416) was an English Christian mystic and theologian known for her spiritual writings and revelations. She is considered one of the most important figures in medieval Christian mysticism. Julian is best known for her work “Revelations of Divine Love,” which is one of the earliest surviving English language books written by a woman.

Julian was born around 1342 in Norwich, England. Little is known about her early life and background. At the age of 30, she fell seriously ill and came close to death. During her illness, she experienced a series of mystical visions that profoundly influenced her spirituality. After her recovery, Julian chose to live as an anchoress, a kind of religious recluse, in a cell attached to the Church of St. Julian in Norwich. This decision led to her being known as Julian of Norwich.

“Revelations of Divine Love”:

Julian’s most significant work is “Revelations of Divine Love,” also known simply as “Showings.” This book is a compilation of her mystical experiences and insights, which she recorded in a series of sixteen visions. These visions are framed as divine revelations given to her by God during her illness.

In her visions, Julian experienced a deep sense of God’s love and mercy, and she believed that God revealed to her the profound truths of divine compassion, redemption, and the interconnectedness of creation. She saw the suffering and sacrifice of Jesus as a powerful expression of God’s love for humanity. Julian’s writing reflects a deep contemplation on the nature

Divine Love and Mercy: The central theme of Julian’s writings is the boundless love and mercy of God. Her visions emphasized God’s unconditional love for all beings.

Redemption and Suffering: Julian’s visions highlighted the redemptive nature of Christ’s suffering and emphasized the importance of understanding suffering as a means of drawing closer to God.

Unity and Oneness: Julian’s mystical experiences led her to perceive the interconnectedness of all creation and the unity of all souls in God’s love.

Feminine Spirituality: Julian’s status as a woman mystic in a male-dominated society underscores her significance in advocating for a feminine perspective on spirituality and theology.

Julian’s writings were likely intended for a broader audience beyond her anchoritic life. Her emphasis on God’s love and compassion stood in contrast to some of the harsher theological perspectives of her time. Her work has been admired for its simplicity, depth, and profound insights into the nature of God.

Today, Julian of Norwich is recognized as an important mystical theologian and spiritual writer. Her “Revelations of Divine Love” continues to inspire readers and scholars interested in exploring the depths of Christian spirituality and the contemplative life.

John Lydgate

John Lydgate (c. 1370-1451) was an English poet of the late Middle Ages, known for his prolific literary output and his contributions to various forms of poetry. He was one of the most prominent poets of his time, and his works cover a wide range of topics and styles.

Lydgate was born around 1370 in Suffolk, England. He likely received a good education and was associated with the Benedictine monastery of Bury St. Edmunds. He entered the monastic life as a young man and spent much of his life there. He had connections with the royal court and various noble patrons, which allowed him to gain recognition for his poetry.

Lydgate was an extremely prolific poet, producing a vast body of work that includes poems, allegories, romances, moral tales, and translations. Some of his notable works include:

“Troy Book” (c. 1412-1420): This is Lydgate’s most ambitious work, a long poem that retells the story of the Trojan War based on Guido delle Colonne’s “Historia destructionis Troiae.” The poem is notable for its extensive descriptions, detailed characterizations, and moralizing commentary.

“The Siege of Thebes” (c. 1420-1422): This is a poetic retelling of the Theban Cycle, focusing on the stories of the sons of Oedipus, Eteocles, and Polynices. The poem explores themes of fate, tragedy, and human folly.

“The Fall of Princes” (c. 1430-1438): This is a translation and adaptation of the work by Boccaccio. It’s a didactic poem that offers moral lessons by recounting the stories of fallen rulers throughout history.

“The Dance of Death” (c. 1430): Lydgate contributed to this allegorical work that portrays Death as a skeletal figure leading people from all walks of life to their inevitable end.

“The Pilgrimage of the Life of Man” (c. 1426): This is a religious allegory that takes the form of a journey, with the protagonist encountering various allegorical figures and moral lessons.

Lydgate’s writing is characterized by his use of rhyme royal, a seven-line stanza with a consistent rhyme scheme, which was popular during his time. He often employed descriptive and elaborate language in his poetry, which contributed to his reputation as a skilled storyteller.

Lydgate’s works were widely read and influential in his era. His ability to adapt classical and foreign sources to the English literary tradition made his works accessible to a broader audience. While some of his works were highly regarded, he faced criticism in later centuries for his extensive output, which led to accusations of verbosity and repetitiveness.

Overall, John Lydgate played a significant role in shaping Middle English literature, and his works provide insights into the literary and cultural landscape of the late Middle Ages.

Thomas Hoccleve

Thomas Hoccleve (c. 1368-1426) was an English poet and contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer. He is best known for his autobiographical poem “The Regiment of Princes” and his contributions to Middle English literature. Hoccleve’s works offer valuable insights into the social, political, and literary context of the late medieval period.

Thomas Hoccleve was likely born around 1368 in London, England. He had a relatively modest background and received an education that allowed him to work as a clerk in various government offices. His career was marked by personal and financial struggles, including mental health issues. Despite these challenges, he left behind a significant body of poetry.

Hoccleve’s writings cover a range of themes and genres, but his most well-known work is:

“The Regiment of Princes” (c. 1411-1420):

“The Regiment of Princes,” also known as “De Regimine Principum,” is an autobiographical poem in which Hoccleve addresses his own experiences and offers advice to rulers and leaders. The poem is dedicated to Henry, Prince of Wales (later King Henry V), and is written in a dialogue format between the author and his patron.

The poem consists of three books, each containing various sections. Hoccleve uses his own life experiences, including his struggles with mental health and personal setbacks, to impart moral lessons and guidance to those in positions of power. The work is didactic in nature, emphasizing virtue, prudence, and humility as essential qualities for rulers.

Hoccleve’s writing style in “The Regiment of Princes” is characterized by rhyming couplets and a mixture of English and Latin. He incorporates personal anecdotes and reflections, offering readers a glimpse into his own life while providing a framework for discussing broader ethical and political themes.

Other Works:

Hoccleve also wrote shorter poems, including satirical pieces and translations. His poem “Complaint” reflects his own struggles with mental health and is considered an important early example of autobiographical writing in English literature.

Hoccleve’s works provide valuable insights into the literary, social, and political concerns of the late medieval period. His autobiographical approach and his exploration of personal struggles set a precedent for later autobiographical writing in English literature. Despite facing challenges, Hoccleve’s dedication to writing and his contributions to Middle English poetry have earned him a place in the canon of medieval English literature.

Margery Kempe

Margery Kempe was born around 1373 in King’s Lynn, England. She came from a well-to-do merchant family and married John Kempe. She became the mother of 14 children. Margery experienced intense religious experiences, including visions, from an early age. She struggled with feelings of sinfulness and a desire for spiritual purity, often seeking guidance from priests and religious figures.

“The Book of Margery Kempe”

Margery Kempe’s most notable contribution is her autobiographical work “The Book of Margery Kempe,” which is considered one of the earliest examples of autobiography in English literature. The book was dictated to scribes, as Margery herself was likely not literate. It offers a unique glimpse into her spiritual journey, personal struggles, and religious devotion.

“The Book of Margery Kempe” is divided into 14 chapters and covers a wide range of topics, including Margery’s mystical experiences, her inner turmoil, her pilgrimages to holy sites, and her interactions with clergy and religious figures. The work is a mix of personal reflection, religious fervor, and interactions with the world around her.

Mystical Experiences: Margery describes her visions and conversations with Jesus, Mary, and other saints. These mystical encounters play a central role in her spiritual life and provide her with a sense of divine guidance and consolation.

Struggles and Devotion: Margery recounts her struggles with temptations and doubts, as well as her intense desire for spiritual purity and devotion to Christ. She expresses her longing for a deeper connection with God and her efforts to live a holy life.

Pilgrimages: Margery embarked on several pilgrimages to holy sites, including Jerusalem, Rome, and Santiago de Compostela. These journeys were both religious and personal, allowing her to seek spiritual enlightenment and share her faith with others.

Interactions with Clergy: Margery’s strong opinions and religious enthusiasm sometimes led to conflicts with clergy and religious authorities. She encountered both support and criticism for her unconventional behavior and mystical experiences.

“The Book of Margery Kempe” provides a unique window into the life and beliefs of an individual woman in the medieval period. Margery’s willingness to share her personal struggles, spiritual encounters, and religious devotion was groundbreaking for its time. Her work sheds light on the role of mysticism, religious experience, and women’s voices within the broader medieval religious landscape.

Margery Kempe’s autobiography offers a valuable perspective on spirituality, gender, and religious expression in the late medieval period, and it continues to be studied and appreciated for its historical and literary significance.

Anonymous Mystery Plays

Biblical Stories: Mystery Plays dramatized stories from the Bible, focusing on key events from creation to the Last Judgment. They covered a wide range of narratives, including the Creation, Adam and Eve, Noah’s Ark, the Nativity, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Judgment Day.

Community Performances: These plays were often performed outdoors, in public spaces like marketplaces or town squares. Entire communities were involved in their production, from planning and casting to set design and performance.

Cycle Plays: Mystery Plays were organized into cycles, also called “corpus Christi cycles,” consisting of a series of individual plays. Each play depicted a specific biblical story or event, and collectively, the cycle covered the entire Christian narrative.

Religious Messages: The primary purpose of Mystery Plays was to convey religious messages and teachings to a predominantly illiterate audience. The plays aimed to engage the audience emotionally and spiritually by depicting familiar biblical stories in a tangible and relatable way.

Mix of Drama and Devotion: While the plays were entertainment, they were also forms of devotion and worship. They allowed the audience to witness and participate in significant religious events, fostering a deeper connection to their faith.

Surviving Plays and Manuscripts:

The surviving Mystery Plays are found in a few extant manuscripts, and they provide valuable insights into the religious and cultural life of the time. One of the most well-known cycles is the York Mystery Plays, which consists of 48 individual plays. The Towneley Plays and the Wakefield Cycle are other notable examples.

Decline and Legacy:

The popularity of Mystery Plays declined in the early modern period due to various factors, including changes in religious practices, social upheavals, and the Reformation. However, their influence can still be seen in later forms of drama, including the development of secular theater.

Mystery Plays offer a unique glimpse into medieval religious practices, theatrical traditions, and the ways in which communities engaged with religious narratives. Today, they are studied for their historical, cultural, and literary significance in understanding the intersection of faith and art in the Middle Ages

Mystery Plays were often organized into cycles, each consisting of a series of individual plays. The specific plays in these cycles could vary, but they generally covered a wide range of biblical stories and events. Some of the well-known cycles and the plays within them include:

York Mystery Plays:

The Creation and the Fall of Lucifer

The Creation of Adam and Eve

Cain and Abel

Noah’s Ark

Abraham and Isaac

The Trial of Mary and Joseph

The Nativity of Christ

The Shepherds and the Angels

The Three Wise Men

Wakefield Cycle (Towneley Plays)

The Creation

The Fall of Lucifer

The Fall of Man

Cain and Abel

Noah and His Ark

Abraham and Isaac

The Sacrifice of Isaac

Jacob and Esau

The Annunciation and Visitation

The Nativity

The Shepherds

The Three Wise Men

The Massacre of the Innocents

The Flight into Egypt

Christ in the Temple

The Baptism of Christ

These are just a few examples of the plays found in the York and Wakefield cycles. Other mystery play cycles, such as the Chester Mystery Plays and the N-Town Plays, also featured a variety of biblical stories, often beginning with the Creation and ending with the Last Judgment.

It’s important to note that the specific plays included in each cycle could vary, and not all cycles included every biblical story. The cycles were created by different communities and guilds, and they tailored their selections to their own religious and cultural contexts.

The York Mystery Plays are a collection of medieval mystery plays that were performed in the city of York, England. These plays are part of a cycle, also known as the York Corpus Christi Plays, and they depict a wide range of biblical stories and events, from the Creation to the Last Judgment. The York Mystery Plays are one of the most famous and well-documented cycles of medieval mystery plays.

Historical Context:

The Mystery Plays originated as part of the Corpus Christi celebrations in medieval England. Corpus Christi was a Christian feast day celebrating the Eucharist, and it often included processions, religious ceremonies, and the performance of dramatic plays. The York Mystery Plays were performed by the city’s various trade guilds, each responsible for presenting a particular play or set of plays.

Performance and Setting:

The York Mystery Plays were performed outdoors in various locations throughout the city, often on specially constructed stages or pageant wagons. These stages or wagons were moved from one location to another, allowing different scenes of the cycle to be performed in different parts of the city. The plays were presented on special occasions, with the entire cycle performed over several days.

Cycle and Stories:

The York Mystery Plays are organized into a series of individual plays, each depicting a specific biblical story or event. The plays in the York cycle include the Creation story, stories from the Old Testament, scenes from the life of Christ, and episodes from the lives of saints. Some of the most well-known plays in the cycle include the Creation and the Fall of Lucifer, the Nativity of Christ, and the Last Judgment.

Guilds and Community Involvement:

Each play in the York cycle was assigned to a specific trade guild in the city. The guild members were responsible for writing, producing, and performing their assigned play. This involvement of various guilds ensured that the performances were a communal effort and allowed for the active participation of different segments of the population.

The York Mystery Plays provide valuable insights into the religious, cultural, and theatrical practices of the late Middle Ages. They were a form of both entertainment and religious instruction, allowing audiences to witness important biblical stories brought to life on stage. The plays also reflect the strong sense of community and collaboration that characterized medieval society.

Today, the York Mystery Plays continue to be performed and studied, showcasing the enduring legacy of medieval drama and its role in shaping English theatrical traditions. The cycles offer a unique window into the intersection of faith, art, and community in the medieval world.

Wakefield Cycle (Towneley Plays)

The Wakefield Cycle, also known as the Towneley Plays, is a collection of medieval mystery plays that were performed in the town of Wakefield, England. These plays are part of a larger cycle, and like other mystery play cycles, they depict a series of biblical stories and events from the Creation to the Last Judgment. The Wakefield Cycle is one of the most well-preserved and extensively documented cycles of mystery plays.

Historical Context

The Wakefield Cycle originated as part of the Corpus Christi celebrations in medieval England. Corpus Christi was a Christian feast day celebrating the Eucharist, and it was marked by religious processions, ceremonies, and dramatic performances. The Wakefield Cycle was likely performed by various trade guilds in Wakefield, similar to other mystery play cycles.

Performance and Setting

The Wakefield Cycle was performed outdoors in different locations throughout the town of Wakefield. Each play was assigned to a specific location, and the stages or pageant wagons were moved from one spot to another to present different scenes of the cycle. This allowed different parts of the town to host the performances.

Cycle and Stories:

The Wakefield Cycle consists of a series of individual plays, each dramatizing a particular story or event from the Bible. The plays cover a wide range of biblical narratives, including stories from the Old Testament, the life of Christ, and the lives of saints. Some of the most famous plays in the cycle include “The Second Shepherds’ Play,” “The Crucifixion,” and “The Last Judgment.”

Characteristics of the Plays:

The Wakefield Cycle, like other mystery play cycles, aimed to educate and entertain the medieval audience through dramatic portrayals of religious stories. The plays often blended religious themes with humor, satire, and local references, making them accessible and engaging for a wide range of people.

Community Involvement:

Similar to other mystery play cycles, the Wakefield Cycle involved the participation of various trade guilds and community members. Each guild was responsible for a specific play or set of plays, and members of the guild would write, produce, and perform their assigned play. This collaborative effort fostered a strong sense of community involvement.

The Wakefield Cycle provides valuable insights into the religious, cultural, and theatrical practices of the late Middle Ages. It reflects the importance of drama as a means of communicating religious messages to a largely illiterate audience. The cycle also demonstrates the creativity and artistic contributions of medieval communities.

Today, the Wakefield Cycle is studied and performed as part of the ongoing exploration of medieval drama and its significance in shaping English theatrical traditions. It serves as a reminder of the intersection of faith, art, and communal spirit in the medieval world

As we conclude this part of our exploration, we stand at a threshold. The voices we have encountered — poets, mystics, dramatists — have shown us the remarkable breadth of Middle English literary expression. From the testing of knightly honour to the mystical apprehension of divine love, from moral allegory to public drama, these works reveal a society in conversation with its deepest values.

As we now turn toward the great historical forces that shaped the closing years of the Middle Ages, we do so with a deeper understanding of the literary achievements that prepared the ground for the Renaissance to come.

From the Professor’s Desk

ABS, The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance