How Printing, Painting, Planets, and Poets Pulled Us Out of the Past

From The Professor's Desk

To understand the Renaissance is to understand your own urge to question, explore, and create. No age is ever truly “modern” without first passing through its own Renaissance.

ABS, The Literary Professor

“The first light of a new dawn broke softly across Europe—one that would soon blaze with the fire of art, reason, and restless curiosity.”

The Renaissance is not merely a period in the history of English literature—it is the moment when the world awoke from a long sleep. And as your professor, I invite you to read this not as a dry chronicle of events, but as an exhilarating journey through an era that shaped the very fabric of the modern mind.

You have already traveled with me through the shadows and resilience of the Old English and Middle English periods. You have seen the warriors and the monks, the ballads and the scribes. But now the story changes. The gaze of man shifts from heaven to earth, from the cloistered scriptoria to the open skies, from Latin prayers to printed vernacular pages.

Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries began to stir, prompted by the ancient whispers of Greece and Rome newly rediscovered. The ink of Petrarch’s sonnets had barely dried when English scholars and poets began to gaze across the Channel with longing eyes. A single invention—the printing press—would soon flood England with ideas faster than ships could sail. Paintings, poetry, telescopes, and treatises all told the same story: the world was larger, stranger, and more astonishing than anyone had dared to imagine.

This was an age of new inventions, new discoveries, new beliefs—and, most importantly for us, new literature. In these coming pages, we will trace how a land of feudal lords and medieval churches slowly transformed into a nation of poets, playwrights, explorers, and thinkers.

We will explore the collapse of old political structures, the brave new world of scientific inquiry, the storm of religious reform, and the explosion of humanist learning. You will meet monarchs who embraced the new and others who resisted it, and poets who experimented with verse forms that would echo through centuries.

Pay close attention. The Renaissance is not an ancient relic. Its spirit hums beneath your very fingertips—every time you read a book, question an old belief, or gaze at the stars. We are still living in its long, unfinished conversation.

Let us begin.

The Fall of the Middle Ages and the First Winds of Change

“Every ending carries within it the seed of a beginning.”

Before we can understand the Renaissance, we must first understand what it was rising from. The Middle Ages—a thousand years long—had grown tired. The once-glorious system of feudalism, with its lords and vassals, serfs and manors, had begun to crack under its own weight. The Black Death had left deep scars on the population, shaking faith in both Church and fate. Crusades had exhausted the coffers of kings and the patience of the people. And yet, even amidst this twilight, new forces were gathering.

Among them was the Magna Carta—signed in 1215 by King John under pressure from his rebellious barons. Though not a Renaissance document in itself, it planted a vital seed: the idea that even kings were subject to law. The notion of individual rights and limited monarchy, however primitive in form, would echo centuries later in the thought-world of the Renaissance and beyond. Thus, it earns its small but rightful place in this narrative.

Meanwhile, Europe was rediscovering forgotten worlds. The ruins of ancient Rome whispered of past glories. Translations of Aristotle, Plato, and Euclid poured into Western Europe, often via the Islamic scholars of Spain. Wealthy merchant cities—Florence, Venice, Bruges—sponsored painters and sculptors who reached back to classical ideals of form and beauty.

At the same time, the very boundaries of the known world were expanding. Italian navigators dreamed of uncharted seas. German craftsmen tinkered with movable type. Reformers challenged the spiritual monopoly of the Church. The idea of “truth” itself was beginning to shift—from the received wisdom of authority to the tested insights of reason and observation.

And England? Though a step behind Italy and France in embracing these currents, it was watching—and waiting. As wars ended and trade routes opened, English scholars, poets, and printers prepared to catch the rising tide. The land of Chaucer and Caxton would soon join the grand European conversation of art, science, and humanism.

Age of Exploration, Reformation, Scientific Revolution, Political Change

“The map of the world was changing—and so was the map of the mind.”

The Renaissance was not a single event but a storm of transformations, sweeping across Europe from the late fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries. Like the tide, it carried with it new ways of seeing, thinking, and believing—and England, though a little late to the shore, was soon caught up in its surge.

The Age of Exploration

In 1492, Columbus—sailing for Spain—set foot in the Americas. Though England’s own maritime adventures would come a few decades later, the psychological impact was immediate and universal. The known world had abruptly doubled in size. What else might lie beyond the horizon?

Exploration changed literature too. The old medieval world of static, hierarchal order began to give way to narratives of adventure, discovery, and questioning. The Renaissance spirit was one of movement—across seas, across disciplines, across the limits of imagination.

The Reformation

Simultaneously, a different kind of voyage was unfolding—into the depths of faith. In 1517, Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to a church door in Wittenberg, sparking the Protestant Reformation. The shockwaves reached England, where debates about the authority of the Pope, the nature of salvation, and the role of the Church fractured long-standing religious unity.

For literature, the Reformation brought new voices and new anxieties. The English Bible, newly translated, gave the common people access to sacred texts in their own tongue. Sermons, pamphlets, and polemics became weapons of belief—and the language of religion grew sharper, leaner, more rhetorical.

The Scientific Revolution

As if exploration and religious reform were not enough, the heavens themselves were under revision. Copernicus posited a sun-centered universe. Galileo, with his telescope, confirmed it. The earth, long believed to be the unmoving center of creation, was now seen as a mere planet among many.

This was not just an astronomical adjustment—it was an existential shock. If the earth was not the center, was man? The very certainty of the medieval cosmos was cracking. Writers, too, responded: metaphysical poetry, philosophical dialogues, and skeptical essays flourished in this climate of doubt and wonder.

Political Change

Back on earth, politics was shifting fast. Feudalism was fading. The rise of strong centralized monarchies—backed by expanding trade and wealth—created new forms of patronage and power. The Tudors, in particular, would leverage this new landscape to foster an unprecedented flowering of English arts.

But with power came peril. Court intrigue, religious factionalism, and the threat of foreign invasion made the English court a dangerous stage—and the pen, as always, was both a mirror and a weapon.

The Printing Revolution: A New Invention That Changed Everything

“Once, knowledge traveled by hand. Now, it would fly on wings of print.”

Of all the engines that powered the Renaissance, none was more transformative than the printing press.

It is no exaggeration to say that the modern world began when words could be multiplied faster than scribes could copy them.

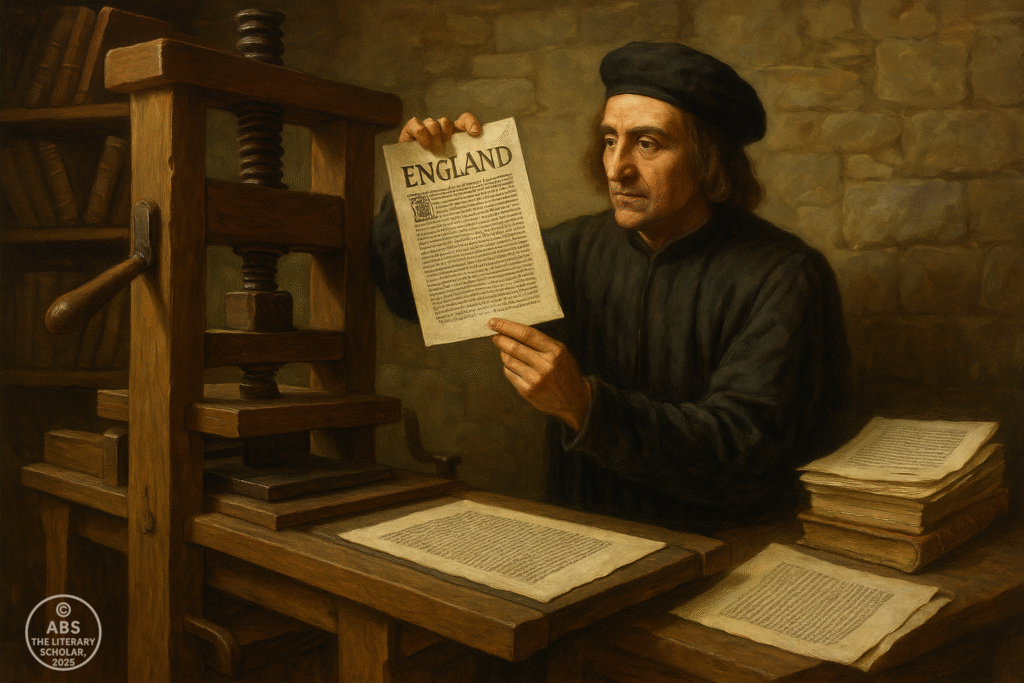

Johannes Gutenberg, a German inventor, had already perfected movable type by the mid-15th century. But it was in England that a man named William Caxton would bring this revolutionary technology to native soil.

In 1476, Caxton set up England’s first printing press at Westminster. His first printed English book, Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, was a translation—but the floodgates had opened. No longer did knowledge reside in cloisters and manuscript rooms. Books could now reach merchants, lawyers, teachers, and even the ambitious commoner.

Why Printing Mattered for Literature

For English literature, this was an earthquake. Suddenly:

Poetry could travel — Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, once known only in limited hand-copied versions, now circulated widely.

The vernacular was legitimized — Printing in English elevated the status of the language itself.

New genres thrived — Ballads, pamphlets, romances, and plays poured from the press.

Humanist learning spread — Classical texts, translated and printed, reshaped literary taste and education.

A New Relationship With Words

Before printing, words were precious and scarce—an expensive luxury. After printing, they became a common currency. Ideas could cross borders and centuries. Writers now wrote not for a handful of patrons but for an ever-growing reading public.

And with that shift, a new kind of literary ambition was born.

The age of Caxton prepared the ground for the flowering of English letters that would soon follow—an age of sonnets, essays, and plays destined not just for noble courts but for the broad stage of history.

New Art, New Religion, New Discoveries, New Cosmic Theories

“To live in the Renaissance was to live in a world whose walls were falling away—revealing infinite new horizons.”

While the printing press gave words new wings, the Renaissance spirit itself was about seeing the world anew—in form, in faith, in geography, and in the heavens.

A New Art Form: The Genius of Leonardo da Vinci

Across the Channel, the brush of Leonardo da Vinci captured not only faces but the very mysteries of life itself.

His Mona Lisa smiled enigmatically. His Last Supper told stories with posture and shadow. His notebooks, crammed with flying machines and anatomical sketches, embodied the Renaissance ideal of the universal man—one who mastered art, science, and philosophy alike.

Though England had no Leonardo, it had eyes that looked toward Italy with admiration. Humanist aesthetics began to influence English poetry and visual culture. Painters, architects, and poets alike sought balance, harmony, and realism—the hallmarks of the Renaissance style.

A New Religion: The Shock of Protestantism

But while artists exalted form, Europe’s religious forms were fracturing.

In 1517, Martin Luther sparked the Protestant Reformation with his Ninety-Five Theses. What began as a theological debate soon reshaped politics, identity, and literature across the continent.

England’s own Reformation was deeply entwined with politics: Henry VIII’s break with Rome led to the creation of the Church of England. But beyond the thrones and decrees, a literary revolution unfolded:

The English Bible, particularly the Tyndale and later King James versions, became literary landmarks—shaping prose style for generations.

Pamphlet wars raged, sharpening English rhetoric.

Religious poetry flourished, rich with spiritual fervor and personal introspection.

The very language of English literature was being tempered in the fires of religious debate.

A New Discovery: Columbus and the Expanding World

Meanwhile, explorers were redrawing the maps. In 1492, Christopher Columbus reached the Americas—a “New World” that would soon alter trade, imagination, and imperial ambition.

For the English literary mind, these discoveries inspired:

Travel literature — blending fact with exotic fantasy.

Metaphors of exploration — poets likened journeys of love, faith, and intellect to voyages across uncharted seas.

Global awareness — a growing sense that the known world was only a fraction of reality.

A New Cosmic Theory: Copernicus and Galileo

But the greatest unsettling news came from the sky.

Nicolaus Copernicus dared to propose that the earth revolved around the sun—a theory Galileo would later defend with his telescope. The cosmic order, long centered on man and earth, was shattered.

Writers absorbed this profound shift:

The metaphysical poets explored the tension between cosmic vastness and human frailty.

Playwrights and philosophers wrestled with destiny, free will, and the place of man in the universe.

The Renaissance mood—part wonder, part anxiety—found its most eloquent voice in this dialogue between the infinite and the intimate.

A New Literature: Utopia, Wyatt, Surrey, and the Seeds of English Renaissance Poetry

“A new world demanded new words—and English writers rose to the call.”

As explorers charted unknown lands and astronomers gazed into unknown skies, English literature, too, was undergoing its own quiet revolution. The Middle English world of Chaucer and balladry was giving way to a more sophisticated, self-aware literary culture—one in dialogue with the Renaissance ideals of humanism, individualism, and classical beauty.

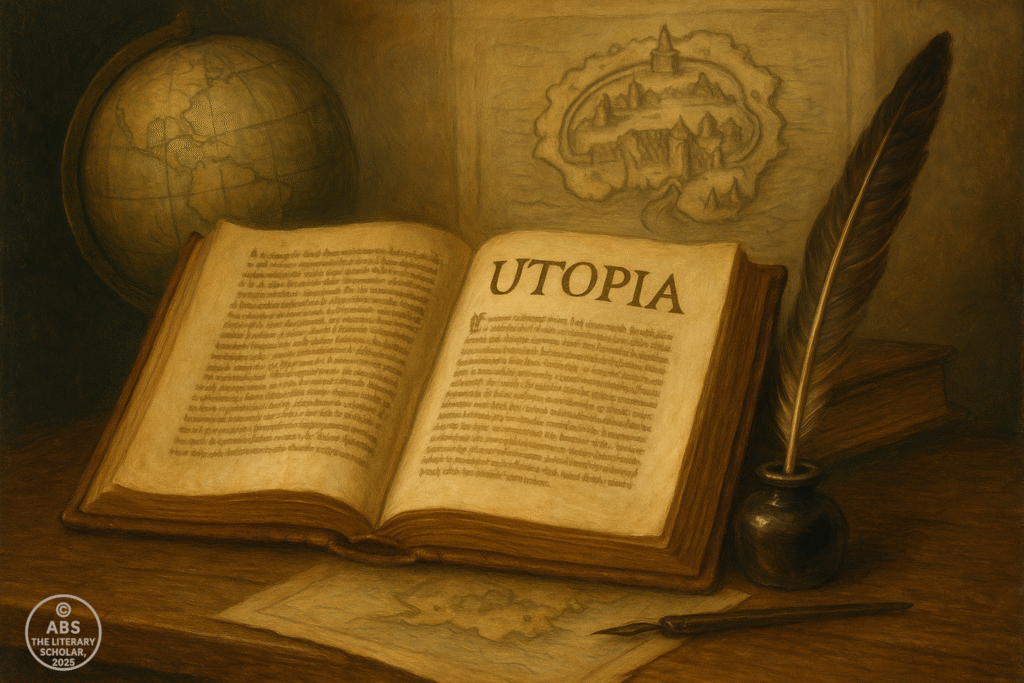

A Seminal Work: Utopia by Sir Thomas More

At the forefront of this transformation stood Sir Thomas More, a statesman, thinker, and writer whose Utopia (1516) captured the restless Renaissance imagination.

Written originally in Latin and soon translated into English, Utopia presented an imagined island society governed by reason, equality, and justice—a bold critique of the corrupt European order.

Why Utopia mattered:

It blended philosophy and fiction, inaugurating a new genre of speculative literature.

It showcased Renaissance humanism—the belief that man could, through reason and virtue, shape a better world.

It enriched English prose style, balancing classical elegance with pragmatic clarity.

Even today, every time we speak of a “utopia,” we echo More’s enduring influence.

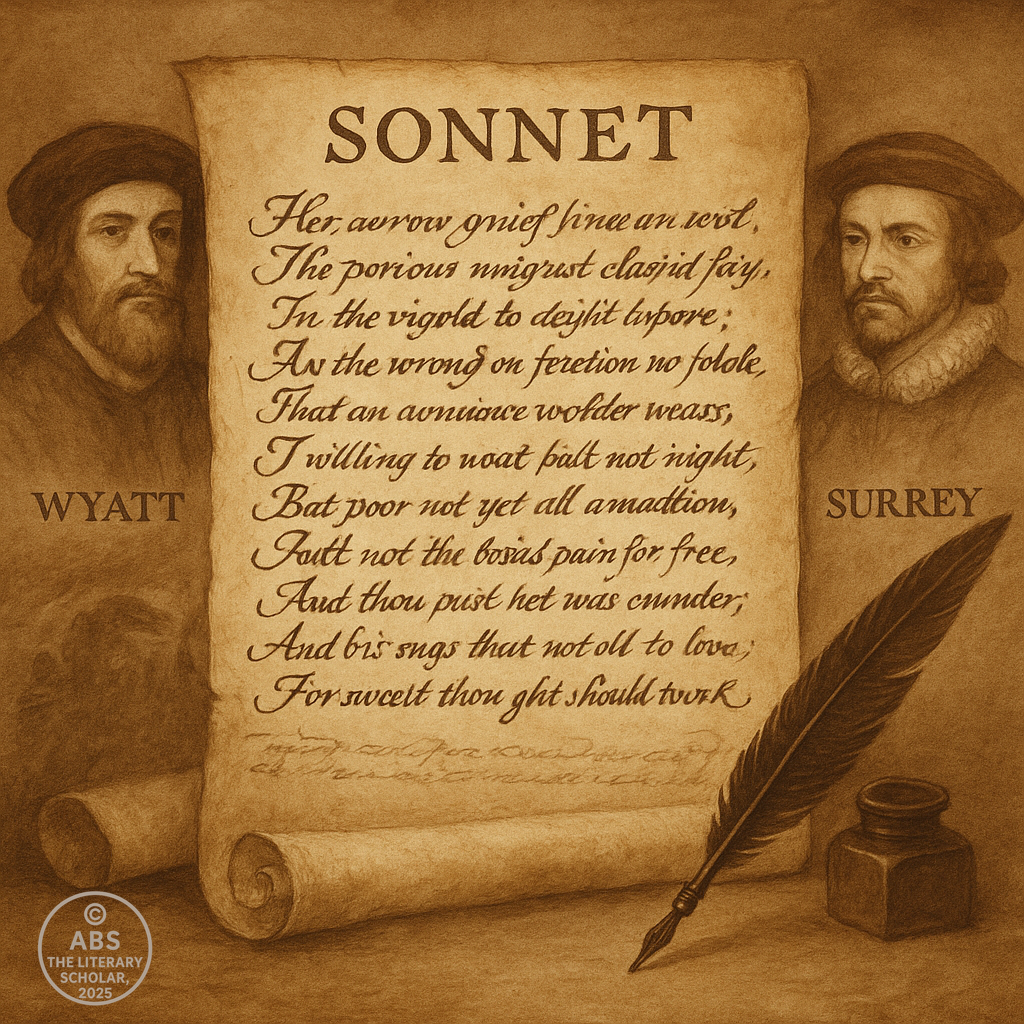

The Birth of the English Sonnet: Wyatt and Surrey

But the Renaissance was not only about grand philosophical works. It was about the refinement of poetic voice.

Enter Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey—two poets whose work marks the dawn of the English Renaissance in verse.

Sir Thomas Wyatt traveled to Italy, where he encountered the sonnets of Petrarch. Inspired, he introduced the sonnet form to England—though with rougher rhythms and heartfelt directness.

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, built upon Wyatt’s innovations:

He helped develop the English (or Shakespearean) sonnet structure: three quatrains and a final couplet.

He pioneered blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter)—a form that would become the backbone of English drama.

Together, Wyatt and Surrey:

Shifted English poetry toward personal voice and lyrical intensity.

Integrated Renaissance ideals of love, beauty, and inner conflict into English verse.

Laid the foundation upon which later giants—Sidney, Spenser, Shakespeare—would build.

The Spirit of Transition

The work of More, Wyatt, and Surrey represents a literature in mid-transition—no longer medieval, not yet fully modern.

It was a literature opening its eyes to classical learning, embracing the humanist spirit, and experimenting with new forms to capture the richness of human experience.

Monarchs and Movements: The Kings and Queens Who Shaped the Renaissance Stage

“Before a golden age of poetry and drama could unfold, a stage had to be built—and monarchs were the unseen architects.”

Though the Renaissance is often told through the names of poets, painters, and philosophers, it was also profoundly shaped by the hands that held the crown. In England, a turbulent sequence of monarchs in the late 15th and early 16th centuries laid both the obstacles and opportunities for the Renaissance spirit to flourish.

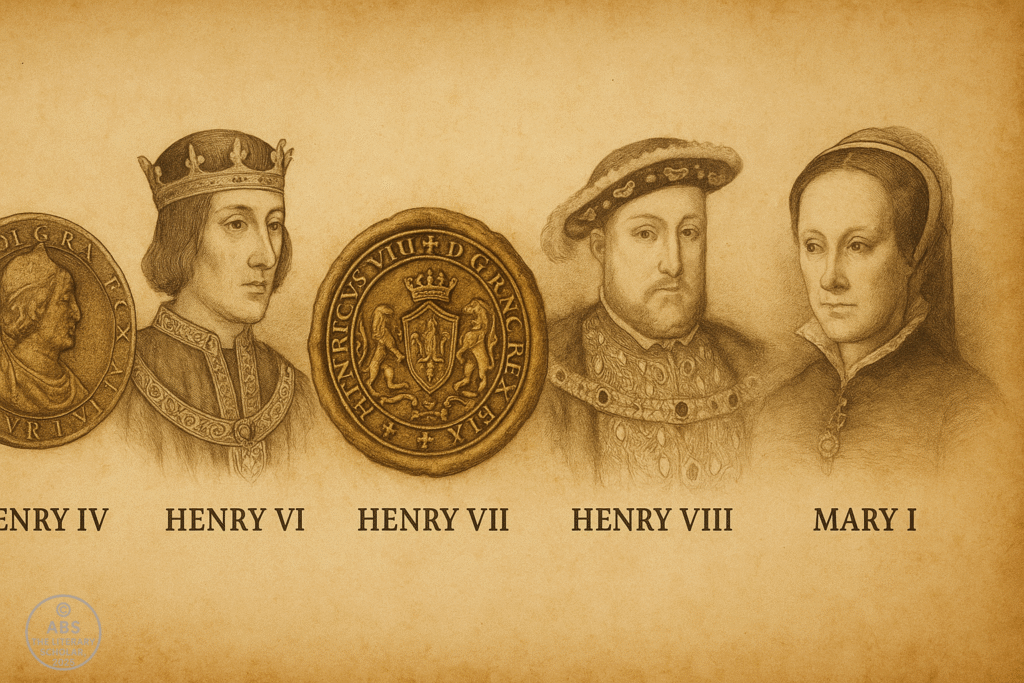

Let us briefly walk through the royal gallery leading up to the Elizabethan stage.

Henry IV to Henry VII: From Turmoil to Stability

The late medieval period had left England politically bruised. The Hundred Years’ War, followed by the bloody Wars of the Roses, pitted the houses of Lancaster and York against each other in a brutal contest for the throne.

Henry IV (1399–1413) had seized the crown from Richard II, inaugurating the Lancastrian dynasty amidst civil unrest.

Henry V (1413–1422) restored a measure of national pride with military triumphs—immortalized by Shakespeare—but his reign was short.

Henry VI (1422–1461, 1470–1471) presided over chaos. His weakness as king deepened factional conflict, plunging England into war.

Edward IV (1461–1470, 1471–1483) and his brief successor Edward V faced constant political intrigue. The shadowy reign of Richard III (1483–1485) ended with his death at Bosworth Field.

Henry VII (1485–1509) then founded the Tudor dynasty, bringing long-sought stability. His reign emphasized consolidation, cautious diplomacy, and the growth of a prosperous merchant class—a fertile ground for Renaissance ideas to take root.

Henry VIII: The Catalyst King

If one monarch embodied the paradoxes of the Renaissance age, it was Henry VIII (1509–1547).

A man of contradictions:

A patron of humanist learning, yet ruthless in suppressing dissent.

A lover of art and music, yet architect of religious upheaval.

A ruler fascinated by Renaissance ideals, yet driven by dynastic obsession.

Under Henry:

The English Reformation severed ties with Rome, altering religious and cultural life.

The royal court became a center of Renaissance culture, attracting scholars, musicians, and poets.

Printing and vernacular literature flourished, encouraged (when politically convenient) by the Crown.

It was an age when the pen was both celebrated and censored—a duality that would shape the tone of English Renaissance literature.

The Curtain Prepares to Rise

Following Henry VIII:

Edward VI (1547–1553) fostered further Protestant reforms but died young.

Mary I (1553–1558) attempted a Catholic restoration, ushering in a period of religious repression and cultural uncertainty.

And then came Elizabeth I—with her would come the great flowering of English letters.

But that is a story for our next scroll.

Professor’s Closing Note

“To study the Renaissance is to study the moment when England, and the world, learned to ask Why not?—instead of Why must it be so?”

From the fading echoes of the medieval world to the first bright notes of modernity, the Renaissance Scroll has traced the bold, questioning spirit of an age that reshaped art, faith, science, and literature.

It is this restless spirit that would soon find its finest voice in the coming Golden Age—an age of dramatists and poets who would give English literature its most enduring works.

But every great movement begins with a whisper of change.

The Renaissance was that whisper—soon to become a chorus.

From the Professor’s Desk

ABS, The Literary Professor

From The Professor's Desk

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance