When theatres thundered with verse, and the common man and the court alike heard the words that shaped an age.

From The Professor's Desk

The Stage Rises

“Before the players spoke their first lines, before the planks of the Globe were hammered into place, the theatre already stirred in England’s restless soul. The poets had prepared the words. Now the words demanded a stage.”

The story of English drama is not simply the story of Shakespeare—though his shadow looms long and luminous across its history. Nor is it merely the story of theatres and their boards, of actors and applause. It is, at heart, the story of a nation finding its voice—a voice shaped by centuries of poetic tradition, but given breath and body through the living presence of performance.

As we traced in Part 1, poetry was the first courtier of Elizabeth’s reign—serving the crown, flattering the Queen, forging the myth of England itself. Yet poetry alone could not contain the energies of the age. The England of the late sixteenth century was a nation awakening to its possibilities: a people increasingly literate, increasingly aware of their place in a rapidly changing world. And with this awareness came a hunger not just for words on parchment, but for words made flesh—spoken aloud, embodied, shared.

It was a hunger that would give rise to one of the most extraordinary cultural phenomena in European history: the birth of the public theatre.

The theatre had long existed in England—but in scattered, impermanent forms. Mystery plays, performed by guilds in market squares; mummers’ dances and pageants; court masques; itinerant troupes offering crude entertainments in taverns and inns. These were the fragments of an older theatrical world—rich in tradition, but lacking both permanence and literary ambition.

That would soon change.

In 1576—less than two decades into Elizabeth’s reign—James Burbage, carpenter and theatre entrepreneur, erected The Theatre in London’s Shoreditch district: the first permanent playhouse in England built specifically for public performances. It was a bold, even risky venture. The theatre, viewed by many as morally suspect, operated in the uneasy space between art and vice, attracting both adoration and condemnation.

Yet The Theatre proved a success—enough to inspire imitators. The Curtain, The Rose, The Swan, and, in 1599, the iconic Globe Theatre, would soon follow, transforming the urban landscape and the cultural life of London.

These playhouses drew audiences of every kind—nobles in private boxes, merchants and artisans in the galleries, groundlings packed shoulder to shoulder in the open yard. The theatre became a great social melting pot, where the distinctions of rank and wealth were temporarily suspended by the shared experience of language and story.

It was a stage upon which not only actors but ideas, ambitions, and anxieties would be performed—reflecting and shaping the consciousness of an entire nation.

And into this charged and hungry space would step a poet from Stratford-upon-Avon—unknown, untested, yet destined to become the voice of his age.

The stage had risen. Now the words would find their players.

Theatrical Culture of the Age

“In the rising playhouses of London, a new kind of crowd gathered—one the poets of the court could scarcely have imagined. Here, the butcher and the baron stood but feet apart. Here, the word became everyone’s to claim.”

As the wooden scaffolds of The Theatre and its successors rose against London’s smoky skyline, so too did a new kind of cultural space—a space where language, performance, and the pulse of a restless city came together in volatile, electric union.

The playhouse was a radical invention. No longer confined to the temporary stages of festivals or the rarefied masques of the court, drama now possessed a permanent home—and one open to all. For the first time, the written and spoken word could address an audience that truly reflected the full breadth of English society.

The experience of attending a play was itself a form of public theatre. The audience was as much part of the spectacle as the actors:

In the galleries, merchants, minor gentry, and well-to-do citizens perched on benches, seeking both entertainment and display.

In the more exclusive private boxes, members of the nobility might attend—sometimes to appreciate the art, sometimes simply to be seen.

But most striking were the groundlings—those who paid a single penny to stand in the open yard before the stage. These were the artisans, apprentices, labourers—the common people of London, their faces upturned, their voices unafraid.

For them, the theatre offered more than distraction. It provided a rare space of intellectual and emotional engagement—where the words of Shakespeare, Marlowe, Jonson, and others spoke to the aspirations and anxieties of the age. In an era of rigid hierarchies, the playhouse offered, if only briefly, a common ground of imagination.

The relationship between the court and the public stage was complex. Elizabeth herself enjoyed theatrical performances and offered patronage to select companies—chiefly the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later the King’s Men under James I). Yet official approval was always tempered by caution. The authorities feared the potential of the theatre to stir unrest, spread subversion, or inflame passions.

Indeed, the theatre remained under constant scrutiny, its scripts subject to official censorship. Yet this tension only sharpened the artistry of the playwrights—who learned to cloak political commentary in allegory, to veil social critique behind the safe façade of historical drama or classical myth.

At the heart of this burgeoning theatrical world were the acting companies themselves. No longer mere itinerant performers, actors had become professionals, bound to specific playhouses and companies, their reputations known across the city.

Names like Richard Burbage—Shakespeare’s great tragedian—and Edward Alleyn, star of Marlowe’s stage, became known beyond the theatre walls. These actors, through their voices and gestures, transformed written scripts into living experience—giving Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Marlowe’s Tamburlaine, and Jonson’s Volpone a presence that lingered in memory long after the last line was spoken.

The theatre was no longer a peripheral entertainment. It had become a national voice—bold, bawdy, beautiful, and unafraid.

Shakespeare’s Early Works — Finding His Voice

“The new stage called for new voices. None would answer more powerfully than the quiet man from Stratford—whose words would soon speak for all of England.”

In the bustling world of London’s theatre, as new playhouses rose and audiences swelled, a young playwright from Stratford-upon-Avon began to make his way.

His name, at first, meant little. The city had its stars: Marlowe, with his thundering blank verse; Kyd, whose Spanish Tragedy packed the playhouses; Greene, sharp-tongued and popular. In pamphlets and taverns, Greene would sneer at this “upstart crow”—a country player presuming to write with the grace of scholars.

But William Shakespeare was not to be dismissed so easily.

Arriving in London in the early 1590s, Shakespeare entered a theatrical world that was ripe for innovation. The newly built theatres needed new plays, and the public appetite seemed boundless. History, comedy, tragedy, romance—all the genres beckoned, and Shakespeare, pragmatic and daring, answered each in turn.

His earliest works bore the marks of learning and imitation, but also flashes of genius. In the Henry VI trilogy and Richard III, he turned the historical chronicle into living drama—blending patriotism, pageantry, and raw human ambition. Richard III, with its charismatic villainy, made a particular impression: audiences thrilled to the Machiavellian rise and fall of the hunchbacked king, voiced in blank verse that crackled with wit and menace.

“And thus I clothe my naked villainy

With old odd ends stol’n out of holy writ;

And seem a saint, when most I play the devil.”

Even in these early plays, Shakespeare’s gift for psychological depth and theatrical instinct shone through. He understood not only how to write great speeches, but how to pace a scene, how to move an audience—skills honed through constant collaboration with actors like Richard Burbage and through acute observation of what London’s diverse audiences craved.

Alongside his histories, Shakespeare explored comedy with equal verve. Plays like The Two Gentlemen of Verona and The Taming of the Shrew demonstrated an early mastery of comic timing, verbal play, and the dynamics of love and power.

“Kiss me, Kate, we will be married o’ Sunday.”

His comedies sparkled with invention: mistaken identities, lovers’ quarrels, joyful resolutions—all staged with an energy that kept both groundlings and gentry rapt.

And then, with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare offered something wholly new: a play where magic, myth, and human folly intertwined in a shimmering web of poetic language.

“The lunatic, the lover, and the poet

Are of imagination all compact.”

Here, he revealed a vision of theatre not merely as mirror but as dream—a space where reality could dissolve, and the deeper truths of love, desire, and imagination might dance upon the stage.

By the end of the 1590s, Shakespeare had already written plays that would ensure his reputation. But the greatest works still lay ahead. He had found his voice—a voice rooted in the rhythms of everyday speech yet soaring with poetic ambition—and the English stage would never sound the same again.

The Globe Theatre — A Cultural Icon

“A theatre of timber and thatch, open to the sky—yet within its wooden walls, the entire world could be staged.”

If Shakespeare’s genius gave voice to the age, it was the Globe Theatre that gave his voice a home—a space where words could take flight, actors could embody kings and fools alike, and audiences could be transported from ancient Troy to enchanted forests to the darkened halls of Elsinore.

By the close of the 1590s, Shakespeare had already established himself as a formidable playwright, with a growing body of popular and respected works. But his fortunes were soon to rise higher still, thanks to a bold venture undertaken by his company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men.

In 1599, the company—seeking greater control over their art and their profits—undertook the construction of a new playhouse on the south bank of the Thames. Using timbers from the dismantled Theatre in Shoreditch, they raised a new, grander structure: the Globe Theatre.

Its architecture was both functional and symbolic. An open-air amphitheatre, circular or polygonal in shape, the Globe featured a thrust stage that extended into the audience, surrounded by three tiers of galleries and an expansive standing yard for the groundlings.

Above the stage flew a flag bearing the theatre’s proud motto: Totus mundus agit histrionem—All the world’s a stage.

And so it was. Within the Globe’s wooden walls, the world was endlessly reinvented:

History came alive with the rise and fall of kings.

Comedy sparked with the misadventures of lovers and rogues.

Tragedy unfolded in soul-searing speeches and silent despair.

The supernatural danced with fairies, witches, and storm-tossed spirits.

The Globe was more than a building; it was a cultural phenomenon—a place where the full range of human experience could be staged and shared. Its audiences were as diverse as London itself: from craftsmen to courtiers, all drawn to the magic of the playhouse.

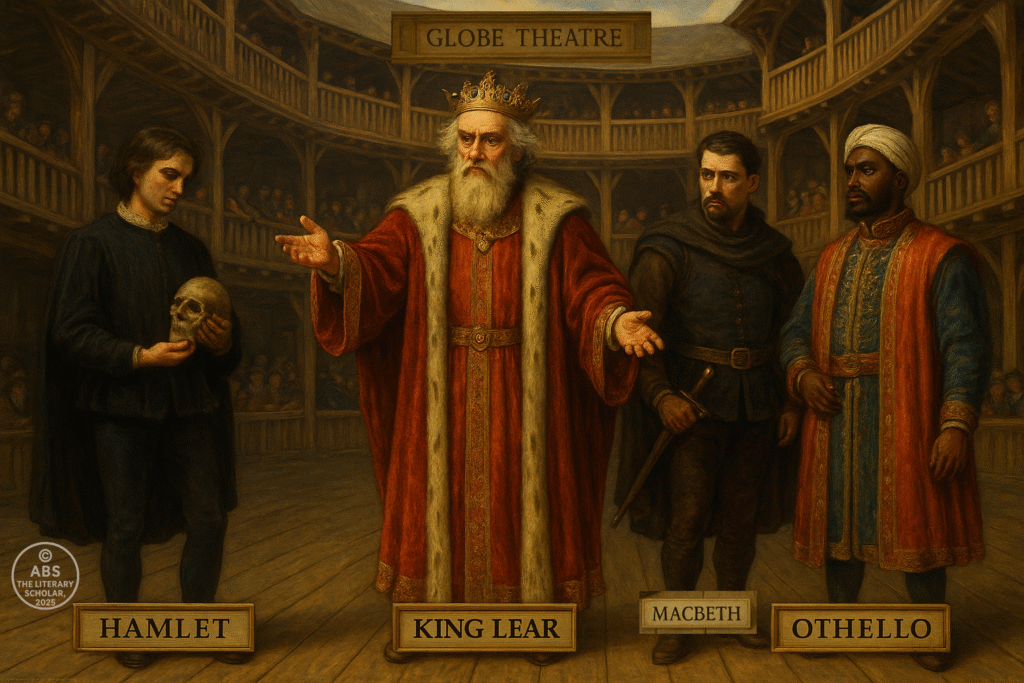

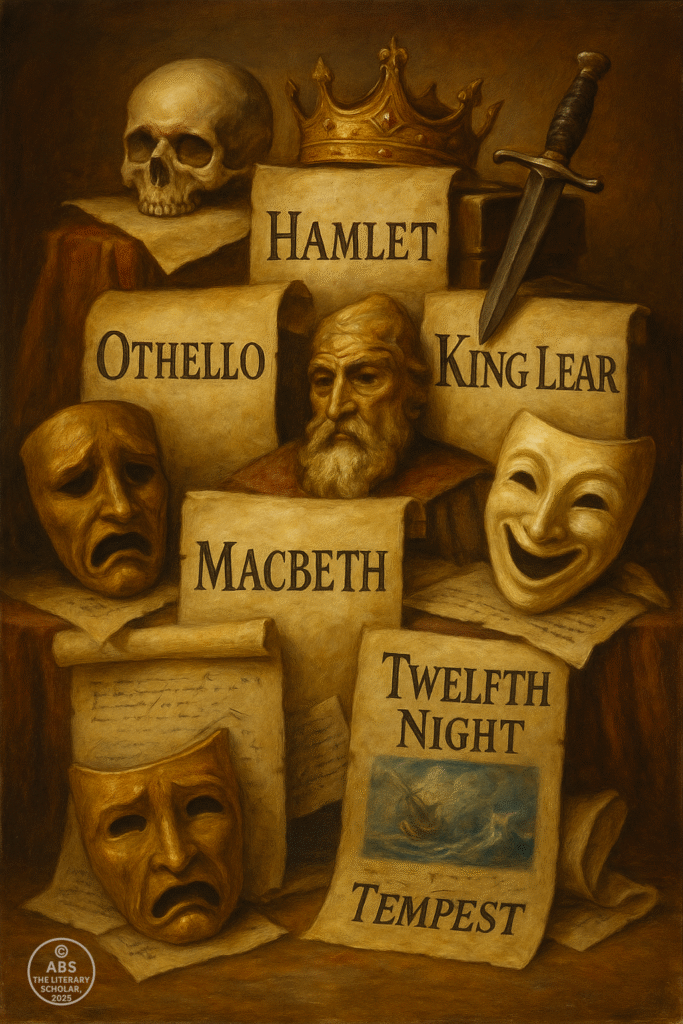

For Shakespeare, the Globe became a laboratory of dramatic experimentation. Many of his greatest works—Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth, Twelfth Night, The Tempest—were written to be performed there, shaped by its space and its audiences.

The Globe’s architecture influenced Shakespeare’s dramaturgy:

The intimacy of the thrust stage fostered direct engagement between actors and audience—soliloquies became confessions shared with the crowd.

The lack of elaborate scenery encouraged Shakespeare’s vivid use of language to conjure place and atmosphere.

The flexibility of staging allowed for rapid scene changes and imaginative theatrical effects.

In this dynamic space, Shakespeare honed a style of drama that was at once poetic and popular, philosophical and playful. His plays spoke to the nobility of kings and the folly of clowns; they probed the deepest questions of existence while delighting in the simple pleasures of the stage.

For the actors, the Globe offered professional stability and a venue worthy of their talents. For the city, it became a beloved institution—a place where, for a few hours, the cares of the world could be suspended in the shared enchantment of story.

The Globe was not merely a stage; it was, in many ways, the heartbeat of the Elizabethan theatre—a place where England found, and celebrated, its voice.

Shakespeare’s Great Period — The Maturity of Genius

“As England’s theatres blossomed, so too did the mind of its greatest playwright. The poet who had once sought the public’s ear now found himself speaking to the human soul.”

By the dawn of the new century, the name William Shakespeare was no longer whispered in taverns or scrawled on playbills—it was spoken with reverence. The “upstart crow” had become the master of the stage, the poet whose words could sway a nation’s heart.

The period from roughly 1599 to 1611 marked Shakespeare’s great creative maturity—a span in which he produced many of the plays that would define not only his own legacy but the very language and soul of English drama.

In the early years of this period, the mood was one of festive mastery. Shakespeare’s comedies of the late 1590s and early 1600s are works of brilliance and joy—comedies that dance with language, with love, with the infinite variety of human folly and delight.

“Sigh no more, ladies, sigh no more;

Men were deceivers ever…”

In plays like Much Ado About Nothing, Twelfth Night, and As You Like It, Shakespeare perfected the form of romantic comedy—creating heroines of wit and will, comic plots of dizzying invention, and closing scenes of harmony hard-won, not cheaply granted.

Yet even amid the laughter, shadows deepened. The human heart, in all its complexity, would soon call Shakespeare’s genius to darker tasks.

Beginning with Hamlet, Shakespeare entered his great tragic phase—a period of astonishing psychological insight and poetic daring. Hamlet is not merely a revenge play; it is a meditation on action and inaction, on life and death, on the nature of being itself.

“To be, or not to be: that is the question.”

The play’s language reshaped English thought, while its prince—a figure of intellect, doubt, and terrible grief—became one of literature’s most enduring icons.

In Othello, Shakespeare explored the corrosive power of jealousy and the tragedy of nobility undone by manipulation. Othello’s fall is rendered with searing intensity:

“Then must you speak

Of one that loved not wisely but too well…”

King Lear, perhaps Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy, stands as a monumental meditation on power, madness, and human frailty. The old king’s descent into despair, stripped of the illusions of rank and pride, is both personal and universal—a vision of humanity confronting its own limits.

“Every inch a king!” Lear proclaims—and in his ruin, we glimpse not only the fall of a monarch but the breaking of a world.

Macbeth, too, is a play of ambition’s dark spiral—a study in moral disintegration. Its language, steeped in supernatural imagery and fatalistic dread, remains among Shakespeare’s most powerful:

“Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow…”

In these tragedies, Shakespeare achieved a depth of psychological realism unmatched in his time—and seldom since. The plays speak not only to their age but to all ages, their themes of love, loss, power, guilt, and identity resonating across centuries.

In his later years, Shakespeare turned once more toward romance and reconciliation. Plays like The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and Cymbeline blend magic, forgiveness, and the wisdom of age. In Prospero’s final speech from The Tempest, we hear perhaps Shakespeare’s own farewell to the stage:

“Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air…”

Thus, in a single creative lifetime, Shakespeare gave England—and the world—a body of work unparalleled in range, depth, and beauty. His plays encompassed the heights of joy and the depths of despair; they mirrored the world as it was, and as it might be.

In the crowded wooden world of the Globe, beneath London’s changeable skies, Shakespeare’s words spoke to the princes and paupers alike—and still they speak, wherever language lives.

The Playwright’s Peers — A Crowded Stage

“The Globe may have crowned Shakespeare, but the streets of London rang with many voices. The Elizabethan stage was no solitary throne—it was a teeming court of competing, colliding, conspiring minds.”

It is tempting, in retrospect, to imagine Elizabethan drama as a stage dominated by a single towering figure. And while Shakespeare’s genius was unmatched, he was by no means alone. The London theatre world of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries was a bustling, competitive, often cutthroat environment—alive with talent, ambition, and experiment.

Playwrights were not isolated artists—they were craftsmen in a thriving industry, writing quickly, often collaboratively, always with an eye to the shifting tastes of the crowd. Their words fed a voracious theatrical machine that demanded novelty, variety, and boldness.

Among the voices that shaped this crowded stage, Christopher Marlowe burned brightest—and most briefly. A playwright of fierce intellect and unmatched poetic force, Marlowe blazed onto the scene with Tamburlaine the Great, electrifying audiences with its grandiloquent verse and sweeping vision of power:

“I’ll march those bloody fields and seek for death!”

Marlowe’s blank verse—unheard in such thunderous form on the public stage—transformed English drama. In Doctor Faustus, he gave tragic grandeur to the scholar who would sell his soul for knowledge—a figure whose ambition mirrored, perhaps, the dangerous allure of the age itself:

“Was this the face that launched a thousand ships

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?”

Marlowe’s death in a tavern brawl at just twenty-nine deprived English drama of one of its boldest voices. Yet his influence lived on—in Shakespeare’s early works and in the heightened expectations of London’s audiences.

Alongside Marlowe stood Ben Jonson—poet, satirist, and dramatist par excellence. Jonson’s plays, such as Every Man in His Humour and Volpone, combined razor-sharp social commentary with a love of classical form. He was a writer who prized craft and discipline, who famously quipped: “Shakespeare wanted art.” Yet beneath this rivalry lay mutual respect.

Jonson would go on to become the leading writer of court masques in the Jacobean period, blending poetry, music, and spectacle to dazzle royal audiences—while never abandoning the keen, critical eye that had marked his comedies.

Thomas Kyd, though less celebrated today, played a crucial role in shaping the era’s most enduring dramatic form: the revenge tragedy. His Spanish Tragedy introduced a style of dark, violent drama that thrilled and disturbed audiences—paving the way for Hamlet and a host of bloody successors.

“Vindicta mihi!” — Kyd’s call for vengeance would echo through English drama for decades.

Nor were these the only voices. The stage teemed with the works of Thomas Dekker, whose Shoemaker’s Holiday brought a warm, bustling vision of London life; Thomas Middleton, whose biting satires laid bare the corruption of court and city alike; and Robert Greene, whose pamphlets and plays captured the energy and anxieties of the capital.

This was not merely a golden age of one man’s genius—it was a golden age of the stage itself, where playwrights sparred, borrowed, rivalled, and sometimes collaborated, all striving to win the favour of fickle crowds and demanding players.

In this crowded, competitive world, Shakespeare’s greatness becomes all the more remarkable. He did not merely rise above his peers—he absorbed their strengths, responded to their innovations, and transformed their techniques into something richer, deeper, and more enduring.

Yet the stage would not have been half so rich without them. The brilliance of Shakespeare’s age lay not in his solitary genius alone, but in the cacophony of voices that filled the London theatres—voices that together forged a dramatic tradition unlike any the world had seen.

Theatrical Themes — What Did They Stage?

“Within the wooden circle of the Globe and its rivals, no world was too distant, no passion too dark, no folly too great. All of human life could be summoned—and was.”

The stage of Elizabethan London was not merely a place for kings and courtiers to strut in borrowed grandeur. It was a space where all of life’s complexities could be explored—a mirror to society, a forge for dreams, a playground for ideas.

The themes that dominated the theatre of this age were as varied as the audiences they served. The groundlings sought laughter and spectacle; the gentry desired eloquence and wit; the scholars and critics looked for moral instruction or intellectual provocation. The playwrights delivered all—and more.

History and Patriotism

In an age of growing national identity, the history play served as a kind of civic catechism. Shakespeare’s Henry IV and Henry V offered audiences stirring tales of England’s past, shaping a collective memory of valor and unity.

“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers…”

Through the retelling of royal triumphs and civil conflicts, the theatre helped forge a vision of England as a nation of destiny—a vision that resonated powerfully in the uncertain political climate of Elizabeth’s later years.

Love and Comedy

Yet the stage was not all trumpets and banners. Comedy flourished, offering both escape and reflection. Plays like Twelfth Night and Much Ado About Nothing explored the absurdities and ecstasies of love, often through mistaken identities, witty banter, and joyous resolution.

“Journeys end in lovers meeting.”

Such comedies provided not only laughter but a gentle critique of social conventions and gender roles, subtly inviting audiences to question the hierarchies of their world.

Revenge and Darkness

The bloodier undercurrents of the age found voice in the genre of revenge tragedy. Following the success of Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy, the genre flourished—culminating in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, a play that elevated the form to philosophical heights.

“Thus conscience does make cowards of us all.”

Here, the stage became a space to confront the moral ambiguities of vengeance and justice, offering catharsis and challenge in equal measure.

Magic and Romance

In his later works, Shakespeare embraced themes of magic, transformation, and reconciliation. Plays like The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream used the supernatural not merely for spectacle, but to explore the deeper truths of human nature.

“We are such stuff as dreams are made on.”

Through enchantment and illusion, these plays invited audiences to consider forgiveness, renewal, and the redemptive power of love—themes that spoke to a nation on the cusp of change.

Moral Questions and the Human Condition

At their best, Elizabethan plays transcended genre to grapple with the fundamental questions of existence. King Lear, Othello, Macbeth—these were not merely tragedies of plot, but meditations on power, identity, fate, and morality.

“Is man no more than this?” Lear cries in the storm—an anguished question that echoes through centuries of theatre.

The Elizabethan stage, in its breadth and boldness, laid bare the full spectrum of human experience. It entertained, yes—but it also provoked, questioned, and consoled. In the words of Hamlet:

“The purpose of playing… is to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature.”

And in this mirror, audiences of every rank saw themselves—their hopes, their fears, their follies, and their noblest aspirations.

The Audience Expands — Theatre as National Voice

“It was not only kings and courtiers who shaped the English stage. It was the citizens of London—the apprentices, merchants, housewives, sailors, and scholars—whose laughter and gasps gave life to the poet’s words.”

As the theatres of London flourished, so too did their audiences. The Elizabethan stage became the busiest and broadest mirror of English society—a space where the nation, in all its variety, came to see itself reflected and reimagined.

In the early years of Elizabeth’s reign, theatre had been largely the preserve of court and church. The mystery plays and masques catered to specific occasions and narrow audiences. But the rise of the public playhouse changed everything.

Now, for the price of a penny, anyone could stand in the yard of the Globe or its rivals and witness the finest poetry, the sharpest wit, and the boldest storytelling of the age. The theatre became the one space in a rigidly stratified society where nobles and commoners shared an experience, even if from different vantage points.

Above in the galleries sat the merchants, professionals, and gentry—seeking both entertainment and an opportunity to display their taste and discernment. Below, in the crowded yard, stood the groundlings: apprentices released from their masters, sailors returned from sea, craftsmen seeking diversion after a day’s toil.

They came for many reasons—for laughter, for spectacle, for the chance to lose themselves in the imagined worlds that unfolded on stage. Yet whether they came in search of kings and battles, of lovers’ quarrels or ghostly whispers, they found something more: a shared voice that spoke to the anxieties and aspirations of the age.

The playwrights, ever attuned to their audience, responded in kind. The plays staged in London were crafted with an extraordinary range of appeal:

Scenes of earthy humour for the groundlings;

Passages of lyrical beauty for the discerning;

Moments of patriotic fervour to stir the national heart;

Dark meditations to satisfy the intellectual appetite.

Through this dynamic exchange, the theatre became more than mere entertainment. It became a national forum, a space where ideas could be aired, where social tensions could be acknowledged and eased through shared laughter or communal tears.

In Shakespeare’s histories, audiences confronted the complexities of English identity. In his comedies, they saw the foibles of love and society playfully exposed. In his tragedies, they faced the stark truths of human ambition, weakness, and mortality.

The theatre’s reach extended beyond the city. Printed editions of plays—quartos and later folios—carried its influence into homes and libraries. Touring companies brought performances to the provinces, spreading the cultural currents of London throughout the land.

By the twilight of Elizabeth’s reign, the theatre had become a voice for the nation—a place where the dreams, doubts, and desires of England’s people found expression. In the words of Henry V:

“Upon the king! let us our lives, our souls,

Our debts, our careful wives,

Our children, and our sins lay on the king!”

It was a voice born of the people as much as of poets—a collective song that resounded from the boards of the Globe to the furthest corners of the realm.

The Legacy — The Lasting Impact of the Stage

“Long after the footlights dimmed, and the players took their final bow, the words remained—alive in the minds of a nation, etched into the soul of its language.”

As the Elizabethan age drew toward its twilight, the world of the English theatre stood transformed. What had begun as a modest experiment—a few scattered playhouses and a handful of daring playwrights—had become a national art form.

And at the heart of this transformation stood the works of William Shakespeare.

Yet Shakespeare’s legacy is not merely a matter of posterity or reputation. His plays—and those of his peers—had already changed the way England thought, spoke, and dreamed by the time they first graced the stage.

Consider the very language. The phrases coined or popularised by Shakespeare alone—“All that glitters is not gold,” “The lady doth protest too much,” “Break the ice,” “Green-eyed monster,”—have seeped so deeply into English that many forget their theatrical origins.

Beyond vocabulary, the plays offered a new emotional vocabulary—a way to articulate love, grief, ambition, jealousy, hope, despair. Characters like Hamlet, Lear, Othello, and Lady Macbeth gave audiences mirrors in which to see their own souls.

Yet Shakespeare did not act in a vacuum. His peers—Marlowe, Jonson, Kyd, Dekker, and many others—enriched the stage with their own bold visions. Together, this generation of playwrights expanded the possibilities of what theatre could do:

It could entertain, yes—but it could also educate, provoke, and transform.

It could speak to kings and commoners alike.

It could give voice to moral questions too dangerous for prose, and to dreams too fragile for courtly speech.

Theatre became not just a pastime, but a public forum, a space where England—torn by religious conflict, exploring new worlds, grappling with its identity—could confront its own image and ponder its future.

As the reign of Elizabeth waned and the age of James I began, the stage remained a vital force. Jonson’s masques would dazzle the Stuart court; Shakespeare’s later plays would explore themes of forgiveness and reconciliation, even as the shadows of coming conflict grew longer.

But the essential legacy was already secure: the English stage had become a national voice, its poets shaping not just entertainment, but the language and imagination of a people.

From the first boards raised at The Theatre, to the bustling life of the Globe, to the printed quartos and folios that carried the plays beyond London’s walls, the words crafted in this golden age continued to resonate.

“O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention!”

And ascend they did. The Elizabethan stage gave us our greatest poetry in motion, our deepest theatrical tradition. Its legacy is not confined to the past—it lives, wherever a line is spoken, a role embodied, a story shared before an audience.

Even now, when the curtain rises and the first words ring out, we hear an echo of that age—of the poets and players who turned a wooden stage into a window on the human soul.

Closing Reflection

From the Desk of ABS, The Literary Professor

“Before the footlights, beyond the applause, what remains is the word. Not the player strutting his hour, but the line that lingers—echoing where the heart is most unguarded.”

The Elizabethan stage was more than a wooden platform beneath an open sky. It was a crucible of language and thought, a theatre of nationhood, a mirror for the inner and outer lives of its time.

Through the pens of Shakespeare and his peers, the stage spoke for England—and taught England to listen to itself. It gave voice to kings and clowns, to vengeful ghosts and star-crossed lovers, to ambition’s rise and love’s undoing, to human frailty and transcendent grace.

It taught that theatre was not mere spectacle, but a living discourse, where the fate of a prince could illuminate the soul of a commoner, and a jest could mask the deepest truths.

As we close this scroll, we leave behind the crowded Globe, the bustling streets, the candlelit scripts. Yet we carry forward the words—and the worlds—they created.

For the English stage, born in this golden age, would never again be silent.

Its echoes will call us forward now, into the next scroll—where shadows lengthen, and the triumph of the Elizabethan imagination meets the darker, more complex theatre of the Jacobean world.

Signed:

From the Desk of ABS, The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance