When the court darkened, the stage deepened—and the players dared to speak the unspeakable

From The Professor's Desk

The Queen is Dead, The Stage Lives On

“The death of a Queen dimmed the light of an era—but in the darkened court and the shadowed streets, the theatre’s fire burned ever brighter.”

The passing of Queen Elizabeth I in 1603 marked not merely the end of a reign, but the close of an age. The Virgin Queen had been more than monarch; she had been the living symbol of England’s Renaissance—a figure who had embodied the nation’s aspirations in verse and pageantry alike.

With her death, the bright pageant dimmed. The glittering optimism of the Elizabethan court gave way to a more ornate, more uncertain Jacobean world. In King James I, England inherited a ruler whose tastes were grand but whose court bred intrigue and disillusionment. The age of Gloriana had passed.

Yet even as the court mourned and recalibrated, the theatres of London remained defiantly alive.

If anything, the death of Elizabeth only heightened the public’s hunger for drama. The theatre had become, by 1603, an indispensable part of English cultural life—a place where news, ideas, and anxieties could be explored in ways no official discourse permitted. The theatres stayed open, the actors kept performing, and the playwrights continued to shape the national imagination.

James, though less politically astute than his predecessor, recognised the value of patronage. One of his first acts as king was to grant a royal patent to Shakespeare’s company—henceforth known as the King’s Men. With this patronage came both protection and prestige, ensuring that the public stage would continue to thrive even as the court grew more complex.

But the plays themselves began to change. The mood of the nation was shifting. The threats of plague, the memory of the Gunpowder Plot (1605), growing religious tensions, and the court’s increasing moral ambiguities all darkened the public consciousness.

Audiences no longer sought merely the heroic tales of England’s past or the playful comedies of love’s folly. They craved something deeper, more unsettling—stories that spoke to the fears and fractures of their world.

The playwrights responded. The golden clarity of the Elizabethan stage gave way to the shadowed complexities of Jacobean drama—a theatre where death, corruption, power, and sexual intrigue took centre stage.

The court itself had changed. No longer presided over by a Queen who embodied national myth, it had become a place of ornate ceremony masking internal decay. The Jacobean playwrights would turn this reality into metaphor—holding up a mirror in which princes and parasites alike saw their true reflections.

Thus began a new chapter in England’s theatrical story. The stage lived on—not in defiance of the court, but as its dark conscience. Where once it had celebrated England’s potential, it now exposed England’s flaws.

In this age of Jacobean shadows, the players dared to stage what the courtiers would not dare to speak.

The Jacobean Stage — A New Age of Drama

“If Elizabeth’s theatres had risen beneath an open sky, now a darker, more intimate stage drew England’s gaze—a stage where whispered fears and unspoken desires found voice in shadow and light.”

The first years of the Jacobean era witnessed a striking transformation of England’s theatrical world. The great outdoor playhouses—The Globe, The Fortune, The Red Bull—still stood, their yards filled with apprentices and merchants. But new spaces were rising to rival them: indoor theatres, more intimate and more exclusive, where plays took on a subtler, darker tone.

Chief among these was the Blackfriars Theatre. Originally a space for private performances, Blackfriars became, under royal patent, a home for the King’s Men during the winter months. Its influence on the craft of drama was profound.

Unlike the vast, sunlit expanses of the Globe, Blackfriars offered a smaller, enclosed environment:

Artificial lighting allowed for subtler visual effects.

Moveable scenery enhanced atmosphere.

Music could be integrated more richly into performance.

Audience proximity enabled more intimate and psychologically complex plays.

The audience itself was changing. At Blackfriars, the seats were filled not with groundlings but with nobility, courtiers, and educated citizens. The plays staged here demanded—and rewarded—a more sophisticated engagement.

This shift was reflected in the works produced. Jacobean drama leaned towards:

Psychological subtlety over grand rhetoric.

Dark satire over patriotic myth.

Personal moral complexity over heroic simplicity.

Erotic undercurrents and explorations of sexual politics.

Yet the public theatres remained vital. The Globe and others continued to draw London’s broad populace—though their fare, too, grew darker. The appetite for sensationalism increased: plays of murder, revenge, incest, and corruption filled the bills. Audiences craved shock as well as beauty, demanding that playwrights push the limits of theatrical convention.

At the same time, the political climate cast a long shadow. The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 had revealed the depths of national tension. Fear of Catholic conspiracy, distrust of court factions, and anxiety over succession haunted the public imagination. The theatre became a space where such anxieties could be explored indirectly—through allegory, history, and tragic invention.

It was an age of theatrical daring. Playwrights took risks—linguistic, structural, thematic—that their Elizabethan predecessors had only begun to imagine. The Jacobean stage spoke in tones of wit, cynicism, sensuality, and despair—tones that resonated with a society facing the cracks in its glittering façade.

The King’s Men thrived in this new environment, staging both Shakespeare’s later masterpieces and the bold new works of his contemporaries. Rival companies—the Prince’s Men, Queen Anne’s Men—competed fiercely, ensuring a vibrant, if brutal, theatrical marketplace.

Thus, the stage of Jacobean London was not merely an inheritance from the Elizabethan past. It was a new creation, shaped by the court’s shifting mood, by public hunger for drama, and by the playwrights’ fearless willingness to stare into the darkest corners of the human soul.

Theatres still rang with applause. But now the words that echoed there carried heavier meanings, richer ambiguities, and a deeper, more unsettling power.

Shakespeare’s Late Works — Magic, Melancholy, and Maturity

“The stage had grown darker, but Shakespeare’s quill grew deeper. In the twilight of his career, he penned not simply plays—but meditations on time, loss, and the fragile grace of forgiveness.”

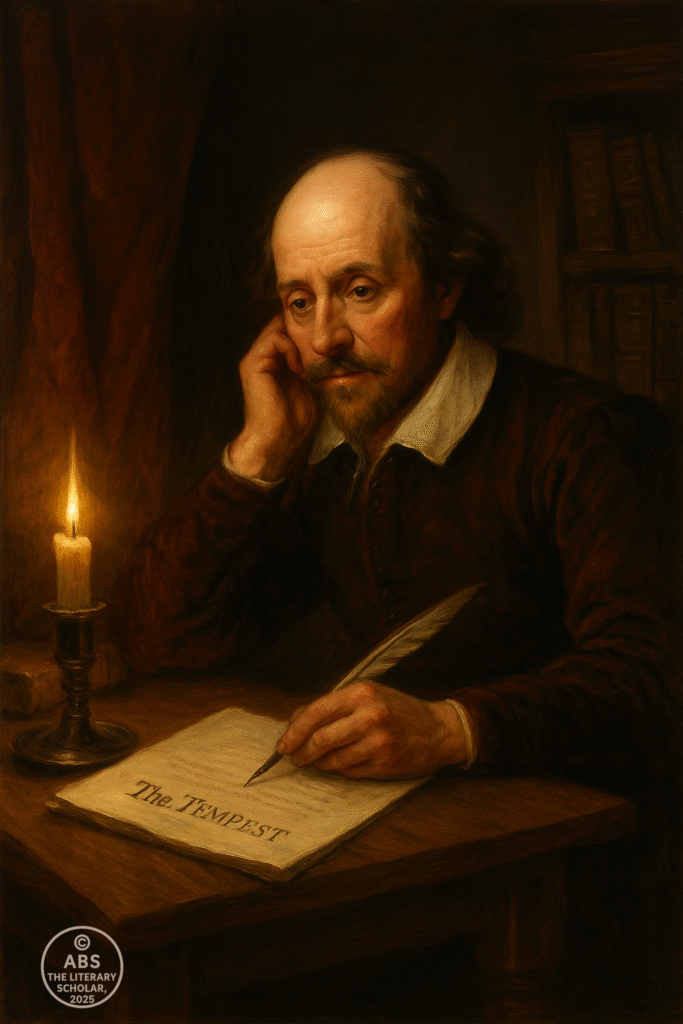

As the Jacobean stage evolved, so too did William Shakespeare. No longer the young playwright seeking to dazzle London with tales of kings and clowns, he had become a master craftsman—his name synonymous with theatre’s highest art.

But with the passing of Elizabeth and the shifting currents of public taste, Shakespeare’s works began to reflect a new sensibility: one of melancholy, of moral complexity, of an older man’s gaze upon a world grown strange and uncertain.

This was an age of late masterpieces—a period when Shakespeare, though still writing for the demanding commercial stage, infused his plays with philosophical depth and emotional resonance unmatched even in his earlier triumphs.

His so-called problem plays—chief among them Measure for Measure and Troilus and Cressida—stood at the threshold of this transformation. These are works of moral ambiguity, where the neat resolutions of comedy give way to unresolved tensions.

“They say best men are moulded out of faults,

And, for the most, become much more the better

For being a little bad.”

In Measure for Measure, questions of justice, mercy, and sexual hypocrisy unfold in a world where virtue itself seems compromised. It is a play that speaks not to the pageantry of court life, but to its private moral shadows—a perfect fit for the Jacobean moment.

Troilus and Cressida pushes further, offering a cynical, almost modern deconstruction of heroism and love. The mythic figures of the Trojan War are here reduced to petty schemers and disillusioned lovers—a bold challenge to audience expectations, and a sign of Shakespeare’s growing willingness to question the very ideals his earlier plays had celebrated.

Yet it is in the great late tragedies that Shakespeare’s Jacobean voice achieves its most profound expression.

King Lear, first performed around 1606, stands as perhaps the ultimate testament to his mature art—a work of shattering power and relentless vision. Here, kings and fools alike are stripped bare; the illusions of power and love are torn apart; the raw elements of nature and human cruelty converge.

“Is man no more than this?”

Lear’s descent into madness is more than personal tragedy—it is a universal meditation on human frailty, suffering, and the search for meaning amid a chaotic world.

Macbeth, too, reveals Shakespeare’s response to Jacobean anxieties. Written in the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot, the play throbs with themes of ambition, treachery, and the supernatural. Its witches and visions spoke directly to an England gripped by fear and fascination with occult forces.

“By the pricking of my thumbs,

Something wicked this way comes.”

In Othello, performed earlier but resonant in this darker age, Shakespeare explored the destruction wrought by jealousy and manipulation—themes painfully relevant to a court rife with factional whispers and betrayals.

“O, beware, my lord, of jealousy;

It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock

The meat it feeds on.”

Yet even amid this tragic grandeur, Shakespeare’s final phase turned toward a gentler, more mysterious light. His late romances—The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline—blend magic, forgiveness, and the wisdom of age.

“Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air.”

In these plays, the harsh certainties of tragedy give way to miraculous reconciliations. Fathers find lost children; broken bonds are healed; the past is not undone, but understood and transformed.

It is as if, standing on the far shore of his career, Shakespeare chose to leave us not with despair, but with hope hard-won through suffering. His romances offer not naive fantasy, but a vision of renewal born from pain, reflection, and grace.

Thus, in the dimming light of his years, Shakespeare’s art did not fade. It deepened—reaching into the darkest chambers of the human heart, and from them drawing forth the fragile gold of wisdom.

On the Jacobean stage, amid shadows and intrigue, his voice remained the clearest and most profound—still guiding us, as it does now, through the complexities of life and art.

The Playwrights of the New Court

“The Jacobean court glittered with artifice—and the stage sharpened its tongue accordingly. If Shakespeare sought reconciliation, others sought revelation: of the blood, the corruption, the inescapable shadow beneath the crown.”

As Shakespeare’s late plays unfolded with wisdom and grace, a new generation of playwrights emerged around him—bold, incisive, and often merciless in their gaze upon the Jacobean world.

The court of James I was a place of spectacle and suspicion. Ostentatious masques vied with whispered plots; outward piety masked private vice. The playwrights of this era seized upon these contradictions, crafting works that peeled back the velvet curtain to reveal the rot beneath.

Chief among these voices was Ben Jonson—Shakespeare’s great contemporary, rival, and occasional collaborator.

Jonson was a man of sharp intellect and sharper tongue. He viewed the stage as a place not for flattery, but for moral instruction and satirical revelation. In plays like Volpone and The Alchemist, he exposed the greed, gullibility, and corruption of London society with biting wit and classical precision.

“Good morning to the day; and next, my gold!

Open the shrine, that I may see my saint.” — Volpone

Where Shakespeare embraced ambiguity and empathy, Jonson demanded clarity and judgment. His characters are not tragic heroes, but grotesques—mirrors held up to a decadent age.

Jonson also became the master of the court masque—a genre blending poetry, music, dance, and elaborate spectacle. Though often dismissed as courtly flattery, Jonson infused his masques with complex allegory and moral critique, subtly challenging the very audience they entertained.

If Jonson wielded satire, John Webster delved into dark tragedy with unparalleled intensity.

In The Duchess of Malfi and The White Devil, Webster conjured worlds of decay and despair, where innocence is crushed beneath the weight of power and corruption. His tragedies are suffused with an almost gothic sensibility—images of skulls, blood, madness, and existential dread.

“Cover her face; mine eyes dazzle; she died young.” — The Duchess of Malfi

Webster’s vision is uncompromising. In his plays, the stage becomes a charnel house, yet one where the most profound truths about human frailty and endurance are laid bare.

Alongside Jonson and Webster stood other daring voices:

Thomas Middleton, whose Women Beware Women and The Changeling explored the intersections of desire, deceit, and violence.

John Ford, whose ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore shocked with its frank portrayal of incestuous love and moral ambiguity.

John Marston, whose acidic wit and dark comedies skewered courtly and civic hypocrisy alike.

These playwrights embraced the full theatrical potential of the Jacobean stage—its capacity to provoke, to unsettle, to confront audiences with the uncomfortable truths of their society.

Their plays spoke not of England’s glory, but of its fears and failings—the human cost of ambition, the corruption of innocence, the fragility of virtue in a fallen world.

In their hands, the theatre became not merely a reflection of the court, but its dark conscience—a space where the sins of the powerful could be staged for all to see.

And yet, even amid the blood and shadow, these works shimmer with a terrible beauty—a testament to the enduring power of language and performance to illuminate the darkest recesses of the human soul.

“Yet even as the playwrights peeled back the darkness of the court, another great literary labour was underway within its walls—one not of blood and betrayal, but of scripture and speech: the making of the King James Bible.”

The King James Bible — The Other Stage of the Word

“As playwrights wrestled with sin and shadow upon the stage, a different company of writers, under royal command, laboured to shape the Word of God itself—into a language both sacred and eternal.”

While the Jacobean theatre plunged deeper into the shadows of human desire and corruption, another, more solemn literary project unfolded under the eye of King James I himself—one that would prove no less influential upon the English tongue: the creation of the King James Bible.

James, though known for his love of court masques and patronage of the King’s Men, was also a deeply scholarly monarch—one who viewed language as a tool not only of political unity, but of spiritual authority.

When he ascended the English throne in 1603, James inherited a nation divided by competing translations of the Bible:

The Geneva Bible—favoured by Puritans for its accessible style, but marred in the King’s eyes by anti-royalist annotations.

The Bishops’ Bible—the official Anglican version, but widely considered clumsy and uninspiring.

James sought to end this confusion—and to assert royal authority over both church and scripture—by commissioning a new translation: one that would be authoritative, poetic, and politically unifying.

In 1604, at the Hampton Court Conference, James ordered that this new translation be undertaken. The task was entrusted to six committees of scholars—around fifty men in all—drawn from Oxford, Cambridge, and Westminster.

Their goal was not to create an entirely new text, but to refine and elevate the best of previous English translations—drawing especially from Tyndale’s pioneering work, while avoiding controversial marginalia.

The translators were instructed to pursue clarity, dignity, and beauty—to craft a Bible that would sound right both in the private ear and in the public liturgy.

“It must be understood of the people, but it must sound as the voice of a king.”

The labour was immense and meticulous. For seven years, the scholars debated, drafted, and redrafted each line—testing its rhythm, cadence, and theological precision.

Finally, in 1611, the King James Bible—or Authorised Version—was published.

Its impact was immediate and lasting:

It became the standard English Bible, used in churches, homes, and public life for centuries.

Its poetic phrasing and sonorous rhythms shaped English prose style for generations.

It gave the English language a host of memorable phrases—“by the skin of your teeth,” “sour grapes,” “a thorn in the flesh,” “labour of love,” and countless more.

In this singular work, the majesty of scripture and the music of the English tongue were fused—creating a literary and spiritual achievement that paralleled, and in many ways counterbalanced, the bold secular art of the Jacobean stage.

Thus, while Webster and Middleton staged corruption and blood in the theatres of London, the translators of the King James Bible sought to craft eternal truths upon the page—each in their way revealing the vast capacity of language to shape the soul of a nation.

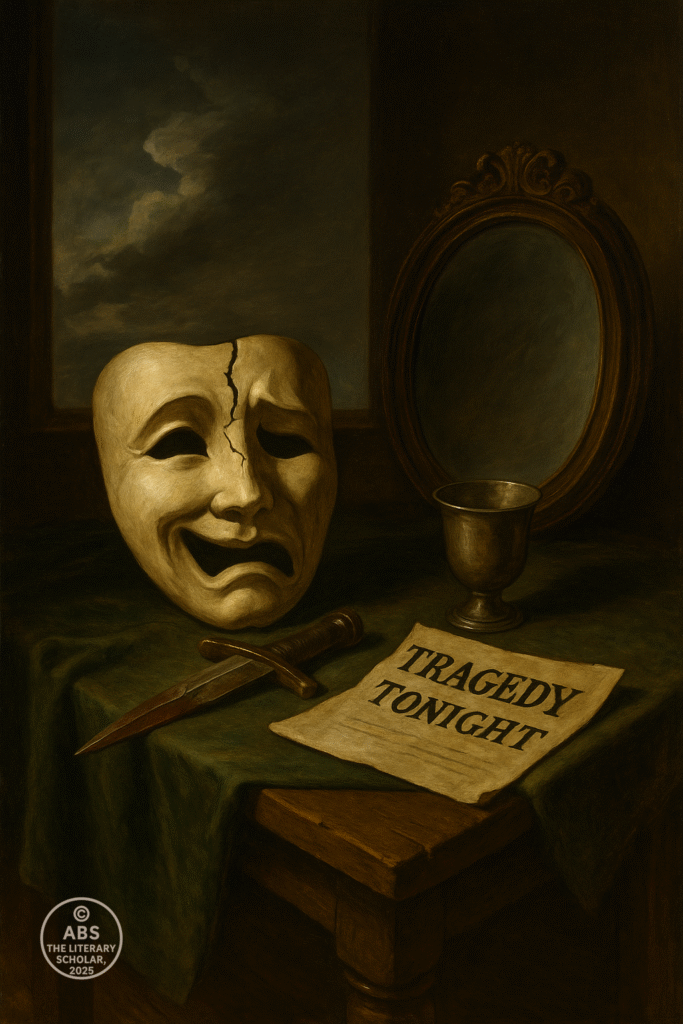

The Themes of Jacobean Drama — Sex, Death, and Power

“If the Elizabethan stage celebrated life’s heights and reconciliations, the Jacobean theatre plunged fearlessly into its depths—where power corrupts, love turns to poison, and death waits behind the velvet curtain.”

The Jacobean playwrights understood their age. They wrote not for a world of ascendant optimism, but for one steeped in uncertainty, cynicism, and moral decay.

Where Elizabethan drama often sought balance and harmony, Jacobean plays reveled in contradiction and excess—in the unsettling truths that their audiences could no longer ignore.

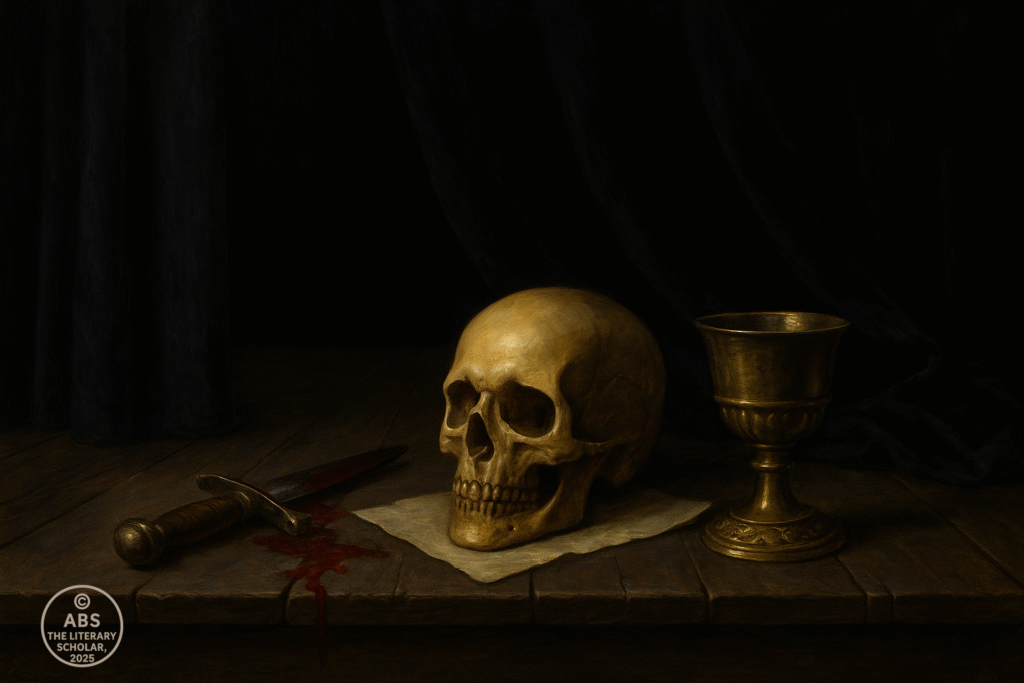

Three great obsessions came to dominate this darker stage: Sex. Death. Power.

Obsession with Death and the Body

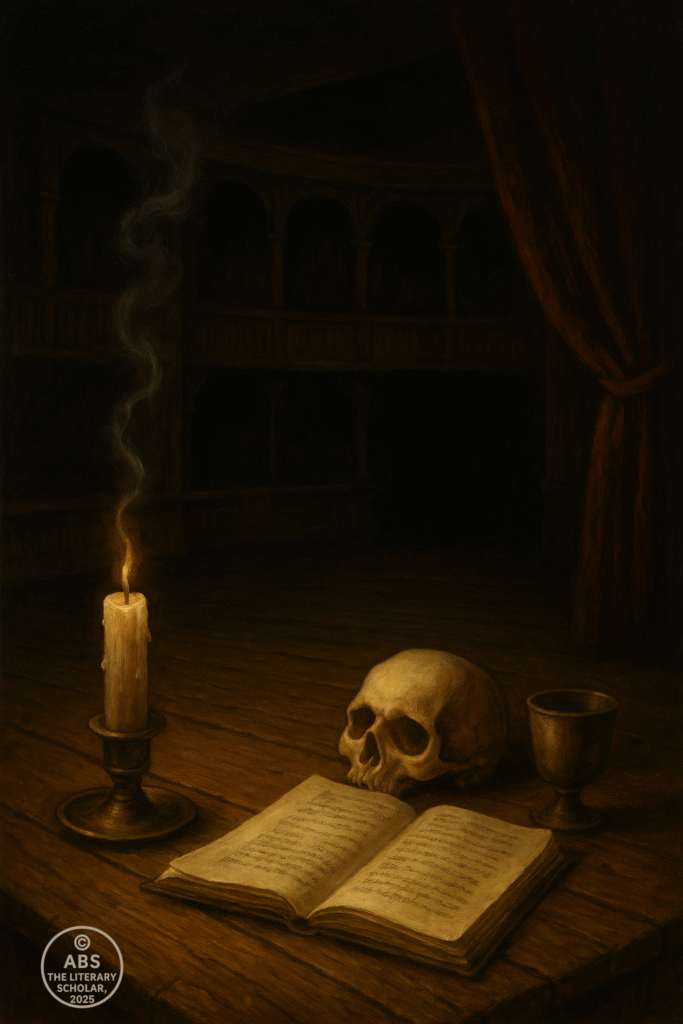

Nowhere is the shift more visible than in the theatre’s fetishisation of death. Jacobean tragedies are strewn with corpses, skulls, blood-drenched altars, and poisoned goblets.

Death is no longer a tragic necessity or solemn closure—it is a pervasive, almost sensual presence, lingering over every scene.

“Cover her face; mine eyes dazzle; she died young.” — The Duchess of Malfi

This morbid fascination reflected a society haunted by plague, political executions, and religious uncertainty. The body, once a vessel of divine grace, became a site of corruption and fragility.

Webster’s vision was perhaps the bleakest: in his world, death is neither noble nor redemptive—merely inevitable, and often meaningless.

Eroticism and Desire

Alongside death came an equally pervasive obsession with sex and desire—not the playful courtly love of earlier comedies, but love twisted by power, manipulation, and violence.

Jacobean drama dared to stage taboo desires:

-

The incestuous love in Ford’s ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore.

-

The dangerous seductions of Middleton’s Women Beware Women.

-

The dark interplay of lust and ambition throughout the tragedies.

Desire in these plays is rarely innocent. It is a force that drives betrayal, moral collapse, and ultimately, death. The playwrights strip away the conventions of romantic idealism, exposing the raw appetites and vulnerabilities of the human heart.

“Kiss me again: let thy lips kill me.” — ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore

Power and Corruption

At the heart of Jacobean drama lies a savage dissection of power—not as noble leadership, but as corrupt, self-consuming ambition.

Courts are portrayed not as centres of justice, but as dens of intrigue and depravity. Princes fall to paranoia; ministers to greed; the innocent are ensnared in webs of lies.

“What a world is this, when what is comely envenoms him that bears it!” — The White Devil

Jonson’s comedies eviscerate the upwardly ambitious, while Webster’s tragedies reveal the moral cost of maintaining power.

The Jacobean playwrights offer no easy catharsis. The wicked often triumph, the virtuous perish, and the survivors are left maimed—physically or spiritually.

Why the Stage Grew Darker

This fascination with sex, death, and power was not mere theatrical sensationalism. It was a profound reflection of Jacobean England’s fractured psyche.

-

The memory of the Gunpowder Plot had shattered illusions of religious unity.

-

James I’s court was marked by faction, scandal, and economic instability.

-

The populace, weary of war and disease, looked to the stage not for comfort, but for confrontation—a theatre that would dare to speak the truths whispered behind closed doors.

Thus, the Jacobean drama embraced the shadow self of England—offering audiences a space where their deepest fears and darkest fascinations could be safely witnessed, examined, and perhaps understood.

In doing so, it achieved a raw, unsettling beauty—one that continues to haunt and inspire the theatre to this day.

The Audience and the Changing Stage

“The words grew sharper, the shadows deeper—and the audience leaned in, hungrier than ever for tales that mirrored their disillusioned age.”

As the plays darkened, so too did the character of the audience—or perhaps it was the audience’s evolving hunger that drew the theatre into such shadowed realms.

By the early Jacobean years, the world outside the theatre had grown harder to ignore. Plague outbreaks periodically closed the playhouses. Political intrigue simmered beneath the surface of royal pageants. The once-vivid dreams of Elizabethan glory had given way to a soberer, more sceptical mood.

Yet the theatres remained packed. If anything, the appetite for theatrical experience had intensified. Audiences no longer craved merely romance and heroism; they demanded spectacle, sensation, and unflinching honesty about the human condition.

The composition of the audience had shifted as well:

In the public theatres like the Globe and Fortune, the standing yard still teemed with groundlings—apprentices, sailors, merchants’ clerks—eager for blood and bawdy humour. They cheered at every well-staged murder, hissed at the villains, and shouted approval for the sharpest jests.

In the private indoor theatres like Blackfriars, a more aristocratic audience gathered—courtiers, noble families, and the educated elite. These spectators prized verbal wit, erotic tension, and psychological complexity—qualities the new playwrights supplied in abundance.

Theatre had become a national habit. Plays were discussed at court, debated in the taverns, and quoted in the streets. Printed quartos of popular dramas circulated widely, extending the theatre’s reach beyond the city.

The audience’s taste for darker material was not mere morbidity. The stage provided a ritual space for confronting the very anxieties that society preferred not to name:

The instability of the monarchy.

The threat of civil unrest.

The moral decay of the ruling class.

The inescapability of death.

The dangers of unchecked desire.

In the charged atmosphere of the playhouse, these fears could be given shape and voice—acted out safely upon the boards, yet resonant with deeper meaning.

The authorities, ever wary of the stage’s power, imposed censorship—but the playwrights grew adept at circumventing control through allegory and metaphor. The audience, equally attuned, learned to read between the lines.

“I am the Duchess of Malfi still.”

Such defiant declarations rang through the theatre, echoing the yearning for integrity and justice in an unjust world.

In this dynamic exchange between stage and audience, Jacobean drama became a vital space of communal reflection—a shared reckoning with the age’s most pressing questions.

The theatre was no longer a mirror for royal myth; it was now the conscience of the nation, speaking truths the court dared not utter. And the audience, with sharpened ear and deepened hunger, came night after night to hear them.

The End of an Era — Theatres and the Coming Storm

“Curtains fall, actors fade, but words—words linger, waiting for a stage yet to be rebuilt. The Jacobean theatre had looked into the abyss—and soon, history itself would step upon that darkened stage.”

By the late 1610s, the glitter of the Jacobean court had grown tarnished. King James’s reign, once hailed with promise, now sagged beneath the weight of faction, scandal, and debt. The court, rife with favourites and intrigue, no longer provided the same fertile ground for dramatic patronage.

And upon the streets, the mood had grown restless. Economic hardship, religious tension, and the slow crumbling of civic trust darkened the public spirit. The stage, ever attuned to the pulse of the nation, reflected this unease.

For Shakespeare, the time to withdraw had come. In 1611, with The Tempest, he offered his farewell to the stage—a play that distilled the wisdom and magic of a lifetime’s work.

“And my ending is despair,

Unless I be relieved by prayer.”

Shakespeare retired to Stratford, where he lived quietly until his death in 1616. His passing marked the symbolic end of an era—an era he had, more than any other, defined.

Yet the theatre did not die with him. The King’s Men continued to perform his works, and new plays still graced the London stage. Jonson, now poet laureate, staged his final masques. Webster, Middleton, and their peers continued to explore the darkest corners of human experience.

But the air had changed. The Puritan movement gained strength, its moralists denouncing the theatre as sinful and corrupt. Parliament, increasingly hostile to royal extravagance and theatrical spectacle, began to impose tighter restrictions.

The outbreak of civil war loomed. Theatres would soon face closure—not from lack of audience, but from political edict. In 1642, with the nation torn by conflict, the playhouses were shuttered by order of the Puritan-led Parliament.

Actors scattered, companies dissolved, and for a generation, the English stage fell silent. The great wooden worlds of the Globe, Fortune, and Blackfriars stood empty—symbols of a vibrant culture now eclipsed by the storm of history.

Yet the words endured. The plays, preserved in print and memory, awaited a new dawn. And when, after the Restoration, the theatres would reopen, they would do so upon the foundation laid by the Elizabethan and Jacobean giants.

Their legacy was not merely in the texts, but in the very language of theatre itself—a language forged in the fires of an age that dared to confront life’s beauty and terror with unflinching art.

The curtain had fallen. The house was dark. But in the silence, the audience of history still listened

Closing Reflection

From the Desk of ABS, The Literary Professor

“The theatre, that bold mirror of a restless age, had shown England its finest hopes and its darkest fears. And when the stage fell silent, those truths remained—etched in words, waiting for voices yet unborn.”

The Jacobean stage dared to explore what the Elizabethan could only hint at. In its shadows we saw the unvarnished faces of power, corruption, desire, and mortality—not through dogma or decree, but through the living, breathing art of drama.

Through Shakespeare’s late masterpieces, through the savage elegance of Webster, the sly brilliance of Jonson, and the audacious provocations of Middleton and Ford, the theatre became England’s deepest public voice—a space where the unspeakable could be spoken, where the unsung could be heard.

And when history’s storm swept the players from their boards, the words remained—not simply preserved on parchment, but alive in the minds of a nation.

For the art of the stage is this: it teaches us to see.

Not merely to watch kings fall or lovers mourn, but to witness our own frailty, longing, and strength—set forth beneath the shifting lights of the human story.

As we close this scroll, we prepare to enter a new chapter—where the silenced theatres, the clash of civil war, and the embers of this great tradition will await their rekindling.

The players may have fled.

But the play is never done.

Signed:

From the Desk of ABS, The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance