When monarchs inspired poets, and poetry crowned a queen — the birth of England’s literary Golden Age.

From The Professor's Desk

“Before the theatre gave voice to the common man, poetry gave shape to the crown.”

“An age of ink and intrigue, of verses whispered in velvet halls and sung beneath the weight of a crown. Before England’s stage could thunder with the words of Shakespeare, its court shimmered with the glitter of poetry—and the figure of a Queen became its muse.”

The Elizabethan Age did not announce itself with the clatter of muskets or the storm of conquests. It emerged, rather, with the turn of a page, the scratch of a quill, the graceful arc of a sonnet’s final line.

Elizabeth I—daughter of Henry VIII, survivor of palace plots, solitary queen—ascended a throne shadowed by religious strife and dynastic uncertainty. Yet in her long and brilliant reign, she transformed England from a precarious island nation into a beacon of culture and ambition. And literature—especially poetry—was her most faithful herald.

The Renaissance spirit that had kindled across Europe arrived in England not only through scholars and artists but through the cultivated court of a monarch who understood the power of the written word. Elizabeth was no passive figurehead. She was a living symbol: Gloriana, the Virgin Queen, whose very body became a metaphor for the state and whose image was endlessly celebrated, adorned, and—yes—manipulated in verse.

The poetic court that surrounded her was both theatre and battlefield. In its mirrored halls, courtiers composed sonnets not merely for love but for favor; they praised the Queen not only from devotion but from ambition. To write was to participate in an intricate dance of wit, loyalty, and survival—a dance that produced some of the finest poetry of the English language.

It is here, in the echoing corridors of Whitehall and Richmond, in the pages of Astrophel and Stella, The Faerie Queene, and countless lesser-known but no less eager verses, that England’s Golden Age truly began—one measured not by gold or conquest, but by the enduring alchemy of word and power.

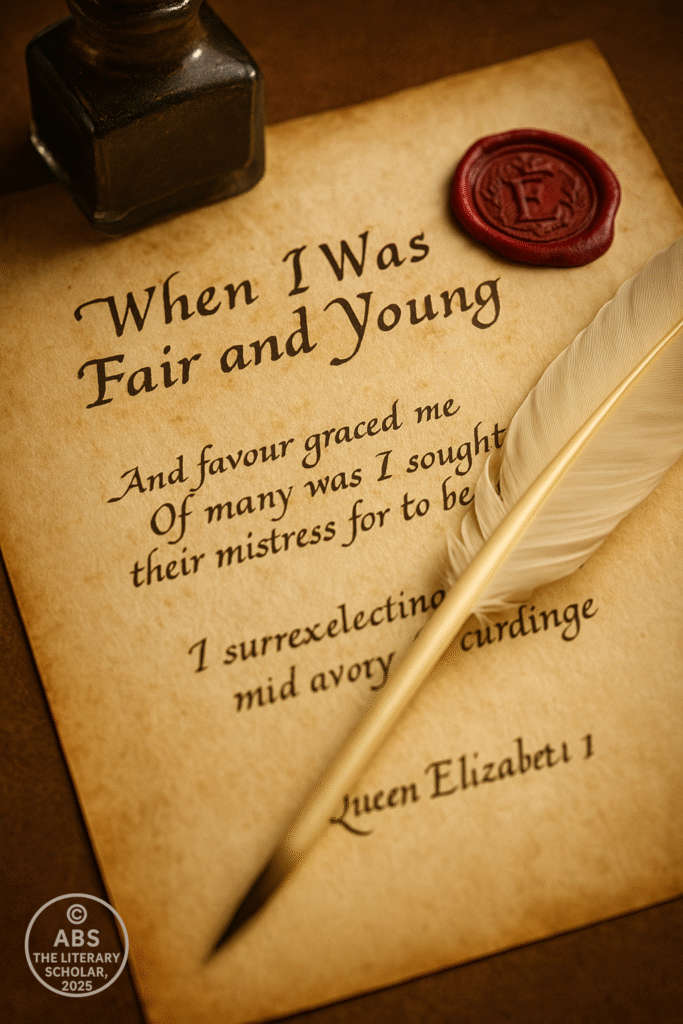

The Queen herself understood this alchemy better than many of her poets. Elizabeth Tudor, for all her political brilliance, was at heart a creature of words. She wrote with a keen sense of audience and tone—whether crafting a rousing speech at Tilbury, a delicate letter to a suitor, or the occasional poem of reflection and regret.

“When I was fair and young, and favour graced me…”

So begins one of her most poignant verses, a meditation on beauty’s fleeting nature and the burdens of power worn upon a woman’s face. In these lines, the monarch speaks not only as ruler but as woman, aging and aware of the cost of her image—crafted as it was into myth by the poets around her.

For those poets, Elizabeth was both an object of worship and a source of endless poetic opportunity. To praise her was to praise England; to court her favor in verse was to court political advancement. Yet, within this game of artifice, genuine creativity flourished. The pressures of court life produced poems of subtlety, wit, and emotional depth—verses that could please the Queen’s ear while speaking truths beneath the lace of metaphor.

Thus, from the Queen’s own pen to the gilded pens of her courtiers, poetry became the lifeblood of the Elizabethan court—a currency of culture, ambition, and survival.

And among those pens, none burned brighter than that of Sir Philip Sidney.

Sidney was everything a Renaissance courtier might aspire to be: soldier, statesman, scholar, poet—and, above all, the embodiment of virtue. His tragic early death at the Battle of Zutphen only deepened the legend, but it is through his words that he remains immortal.

In Astrophel and Stella, Sidney wove the conventions of courtly love into a deeply personal exploration of longing, restraint, and intellectual play. Here was a poetry that mirrored the life of the court itself: a world where emotion must be veiled, desire controlled, and every word carefully chosen.

“With what sad steps, O Moon, thou climb’st the skies!

How silently, and with how wan a face!”

Sidney’s influence extended beyond the sonnet sequence. In his Defence of Poesie, he provided the intellectual justification for poetry’s role in society—arguing that poets could instruct and inspire in ways no dry philosopher could achieve. It was a bold stance in a time when Puritan voices sought to diminish the value of the arts.

At Elizabeth’s court, Sidney’s example fused moral seriousness with poetic grace—setting a standard that would shape the work of his contemporaries and successors.

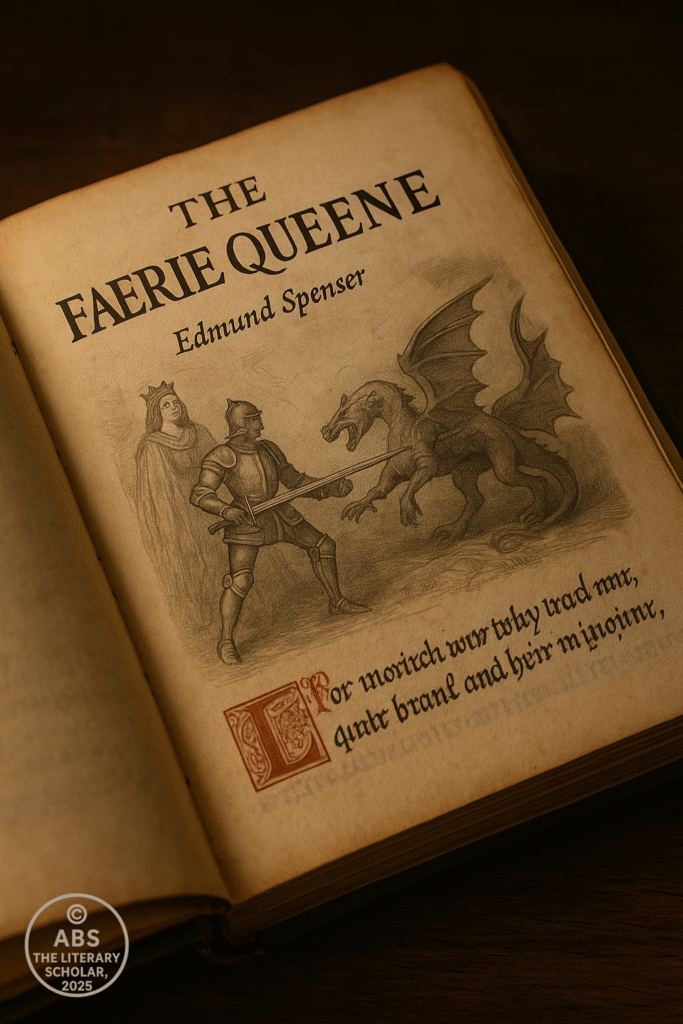

Yet if Sidney’s poetry refined the inner life of the courtier, it was Edmund Spenser who sought to capture the very soul of England itself.

Spenser was not born to courtly privilege, but he understood the court’s language—and its power. In his monumental The Faerie Queene, he crafted a sprawling allegory that flattered Elizabeth, celebrated chivalric ideals, and forged a mythic identity for the nation.

“And unto her a thousand tongues did frame

Congratulation of her glorious name.”

The figure of Gloriana—Elizabeth as eternal Queen—dominated the poem’s imaginative landscape. Yet within its enchanted forests and allegorical battles lay more than flattery. Spenser sought to articulate a vision of virtue, national destiny, and the struggle between good and evil.

The Faerie Queene was a poem of its time and beyond it: a patriotic epic written in a newly minted poetic form, the Spenserian stanza, and designed to foster a uniquely English literary tradition. In doing so, Spenser elevated the court’s poetic culture from mere ornamentation to a force of cultural nation-building.

Spenser’s relationship with the court, however, was complex. Though he aspired to favor, he remained in many ways an outsider—a poet whose heart lay in the landscape of English myth as much as in the polished dance of courtly ambition. Through him, poetry became both a mirror to the court and a mirror to England itself—reflecting its aspirations, contradictions, and future.

If Sidney gave the court its voice of noble yearning, and Spenser forged the epic soul of the nation, then Sir Walter Raleigh embodied the restless, worldly ambition of the Elizabethan age.

A poet, courtier, explorer, and sometime prisoner of the Tower, Raleigh’s life traced the volatile arc of courtly favor—rising through daring service and sharp wit, then falling from grace under a less forgiving monarch. But in the glittering years of Elizabeth’s reign, Raleigh stood at the Queen’s side, both her defender and her poet.

“Even such is time, that takes in trust

Our youth, our joys, our all we have…”

In his poems, Raleigh reveals the undercurrents of disillusionment and mortality that ran beneath the court’s polished surfaces. Unlike the elaborate allegories of Spenser or the high-minded idealism of Sidney, Raleigh’s verse often confronted the stark realities of ambition, aging, and the fickle tides of power.

Yet he was no stranger to the court’s poetic games. His odes to the Queen balanced sincere admiration with calculated artistry—each line both a tribute and a subtle act of self-positioning. Raleigh understood that in the Elizabethan court, words were weapons as well as gifts.

Beyond the palace walls, Raleigh’s pen was equally bold. As an explorer and chronicler, he helped shape England’s vision of the wider world—a vision that bled into the imagination of its poets. The New World, the sea, the shifting maps of empire—all found echoes in the literature of the time, infusing English poetry with a global consciousness that would only grow in the centuries to follow.

In Raleigh’s life and works, we glimpse the full complexity of the Elizabethan poet: a servant of the crown, a seeker of fortune, a voice of personal truth amid public performance.

If Sidney gave the court its voice of noble yearning, and Spenser forged the epic soul of the nation, then Sir Walter Raleigh embodied the restless, worldly ambition of the Elizabethan age.

A poet, courtier, explorer, and sometime prisoner of the Tower, Raleigh’s life traced the volatile arc of courtly favor—rising through daring service and sharp wit, then falling from grace under a less forgiving monarch. But in the glittering years of Elizabeth’s reign, Raleigh stood at the Queen’s side, both her defender and her poet.

“Even such is time, that takes in trust

Our youth, our joys, our all we have…”

In his poems, Raleigh reveals the undercurrents of disillusionment and mortality that ran beneath the court’s polished surfaces. Unlike the elaborate allegories of Spenser or the high-minded idealism of Sidney, Raleigh’s verse often confronted the stark realities of ambition, aging, and the fickle tides of power.

Yet he was no stranger to the court’s poetic games. His odes to the Queen balanced sincere admiration with calculated artistry—each line both a tribute and a subtle act of self-positioning. Raleigh understood that in the Elizabethan court, words were weapons as well as gifts.

Beyond the palace walls, Raleigh’s pen was equally bold. As an explorer and chronicler, he helped shape England’s vision of the wider world—a vision that bled into the imagination of its poets. The New World, the sea, the shifting maps of empire—all found echoes in the literature of the time, infusing English poetry with a global consciousness that would only grow in the centuries to follow.

In Raleigh’s life and works, we glimpse the full complexity of the Elizabethan poet: a servant of the crown, a seeker of fortune, a voice of personal truth amid public performance.

Yet the poetry of the Elizabethan court was not the sole domain of its glittering favorites. Beyond the commanding figures of Sidney, Spenser, and Raleigh, a vibrant constellation of voices shaped the literary atmosphere of the age—voices that often shimmered in the margins, occasionally breaking through the centre stage.

In every corner of England, poets responded to the cultural moment in which they lived—an age of exploration and uncertainty, faith and fracture, power and spectacle. Some found patronage at court; others published their works for a growing audience of readers, increasingly literate and eager for verse. The printing press had widened poetry’s reach, transforming it from an elite art into a shared cultural currency.

Among these wider voices stood figures such as George Gascoigne, whose sharp wit and adaptable style bridged the old courtly forms and the new public tastes. In his Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, Gascoigne explored love, satire, and morality—always with a keen sense of the shifting fashions of verse and favor.

Michael Drayton, too, contributed richly to the poetic tapestry. His historical poems and sonnets celebrated England’s past and present, lending the national mythos a personal lyricism. In poems like Poly-Olbion, Drayton sought to map not only England’s rivers and hills but its very cultural spirit.

Samuel Daniel, a quieter yet deeply influential voice, brought a philosopher’s calm and a stylist’s grace to his poetry. His sonnet sequences and meditative works explored the tensions between personal feeling and public duty—a theme that resonated powerfully within the hierarchies of the court.

Nor were these poets isolated from the grander literary currents of the age. They conversed in verse—responding to each other’s works, borrowing forms, refining themes, challenging conventions. The poetic court of Elizabeth was as much an intellectual salon as it was a social theatre—a place where wit and erudition were prized as highly as loyalty and lineage.

And beyond these male voices, the age also saw the rise of women as literary patrons—and, when opportunity permitted, as writers in their own right.

If poetry flowed from the pens of men, it often survived and flourished through the patronage of women. In a court defined by the figure of a Queen, it is no surprise that women held a significant, if often understated, role in shaping the literary life of the age.

Foremost among these was Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke—a noblewoman of exceptional intellect and literary sensibility. Sister to Sir Philip Sidney, she did more than preserve her brother’s legacy; she extended it. Under her patronage, the Sidney circle of poets and thinkers became a crucible of literary innovation.

Mary Sidney herself translated psalms with poetic beauty and precision, and her gatherings at Wilton House offered a space where poets could experiment with form and philosophy beyond the rigid expectations of the court. In an era when women’s voices in print were rare, her influence resonated powerfully—not through noisy proclamation, but through cultivated silence and carefully shaped patronage.

Around her, other women, too, engaged with the literary culture of the time. Some composed poems circulated privately in manuscript—occasional verses, elegies, meditations. Others acted as discerning readers and supporters, their influence felt in the choices of publishers and in the themes poets explored.

The image of Elizabeth herself—as both monarch and muse—cast a long shadow over this feminine literary presence. On the one hand, the Cult of Gloriana celebrated an idealized, chaste, and sovereign womanhood. On the other, it constrained the roles women could publicly assume. Within this tension, women like Mary Sidney carved out spaces of intellectual agency, subtly reshaping the poetic culture from within.

Thus, beneath the loud public voices of the Elizabethan court, a quieter current flowed—a current sustained by the wisdom, patronage, and occasional verse of women, whose contributions, though less recorded, were no less vital to the age’s literary flowering.

While the court remained the glittering centre of literary prestige, the world beyond its marble pillars was stirring with its own hunger for verse. The spread of printing in England had transformed poetry from an elite art into a public phenomenon—accessible, adaptable, and increasingly commercial.

William Caxton’s press, introduced in the late fifteenth century, had opened the door; by the time of Elizabeth’s reign, London teemed with printers, booksellers, and stationers, each eager to meet the growing appetite for poetry. The once-guarded treasures of courtly manuscripts now appeared in print, often with or without the consent of their authors.

Poetry entered the marketplace, and with it came both opportunities and tensions. For the first time, a poet might write for a wider public—not solely for a patron’s favor. The printed sonnet sequence, pastoral dialogue, or moral ballad could reach the merchant’s wife, the student, the London apprentice. The audience for verse had broadened, and poets adjusted their voices accordingly.

Some, like Michael Drayton and Samuel Daniel, embraced this shift, publishing works that spoke not only to courtly ideals but to national identity, personal reflection, and the common reader’s experience. Others, more cautious or more proud, hesitated—fearful that public print might cheapen the subtle art of poetry, or expose them to vulgar critique.

Yet there was no turning back. Poetry was becoming a public art—an art performed not only in court masques or whispered in private salons, but sold on London’s streets, read aloud in taverns, discussed in gatherings of merchants and scholars alike.

The printing press had blurred the lines between elite and popular culture, giving poetry a reach and influence it had never known. In this new landscape, the words of Elizabethan poets found fresh life—printed, purchased, read, remembered.

The poet’s quill still danced for the Queen’s eye, but it now danced also for England’s people, in a dialogue that would soon reshape the very nature of literary culture.

It would be a mistake to imagine the Elizabethan literary world as a narrow stage occupied solely by its most famous players. Beyond the polished sonnets of Sidney, the epic ambitions of Spenser, and the restless lines of Raleigh, there thrived a broad community of poets—each contributing, in their own measure, to the rich texture of the age.

These were the minor poets—though “minor” is a term of convenience rather than judgment. They included courtiers of lesser favor, scholars seeking reputation, professional writers balancing art and income, and anonymous voices whose verses flickered briefly in print before history’s gaze moved on.

George Gascoigne was one such figure—a versatile poet and playwright whose Hundreth Sundrie Flowres demonstrated a remarkable adaptability of tone and form. Gascoigne’s work ranged from courtly lyric to satire, from love poems to moral reflections—each marked by an acute awareness of the audience’s shifting tastes. His writings capture the transitional spirit of the era: rooted in tradition, yet alert to the winds of change.

Thomas Lodge, another poet of this wider circle, brought pastoral elegance to the stage and page alike. His Rosalynde would inspire Shakespeare’s As You Like It, a testament to the permeability of literary forms across genres. Lodge’s poetry, with its blend of classical allusion and Elizabethan freshness, embodied the era’s dialogue between old and new.

Figures such as Michael Drayton, with his patriotic chronicles; Samuel Daniel, whose philosophical poise gave English poetry a quieter strength; and Henry Constable, whose sonnets glowed with spiritual intensity—all contributed to an expanding literary ecosystem.

In their works, we glimpse a world of poets conversing across court and city, across printed page and spoken performance. They borrowed from one another, answered each other in verse, and collectively shaped the evolving language of English poetry.

This was no mere courtly ornamentation; it was a vibrant, competitive, and often collaborative culture—where poets strove not only for favor, but for immortality in words. And as their verses spread through print, through performance, and through the informal networks of manuscript circulation, they laid the groundwork for an even broader literary flowering to come.

If the printed word carried poetry to England’s streets, it was often the quiet force of female patronage that sustained and shaped its course at court. In an age when public authorship was still a fraught space for women, many chose instead to exercise their influence through the careful cultivation of poets and poetry—their salons, libraries, and correspondence serving as informal academies of literary life.

Foremost among these was Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke. Widowed young yet immensely powerful, Mary Sidney inherited not only the estates of her late husband but also the intellectual mantle of her brother, Sir Philip Sidney. Under her guidance, Wilton House became a centre of literary excellence—a place where poets gathered, translated, composed, and debated.

Mary Sidney herself was no passive patron. Her translations of the Psalms displayed both poetic mastery and spiritual depth, while her critical engagement with contemporary literature helped refine the works of those she supported. In the age of Gloriana, it was fitting that another formidable woman should stand as a beacon for England’s poets—though from the shadows of private influence rather than the blaze of the throne.

Other noblewomen followed her example. Though most did not publish openly, their correspondence and commissioned works reflect a sophisticated engagement with poetry. Manuscript collections often contain verses attributed to unnamed “Ladies of the Court”—their anonymity a shield against scandal, their words a testament to their literary presence.

Some wrote occasional poems for court masques or private gatherings; others acted as crucial intermediaries between poets and patrons. Their influence shaped what was written, what was performed, and even what was published.

In a culture where the Queen herself served as both the ultimate patron and the subject of countless verses, it is unsurprising that women beyond the throne sought, and found, their own spaces in the literary landscape.

Through patronage, performance, and pen, they helped ensure that poetry remained a living, evolving force—one that reflected not only the ambitions of men but the subtle power of women’s voices, heard and felt across the age.

If poetry ruled the court in the early years of Elizabeth’s reign, by the closing decades another force was stirring—one that would soon reshape the entire landscape of English letters. From the shadows of court masques and private performances, the public theatre was rising.

The roots of this transformation lay within the court itself. Masques, those elaborate spectacles of poetry, music, and dance, had long been a favourite form of aristocratic entertainment. In these performances, the lines between poetry and drama blurred: courtiers spoke in verse, mythic allegories unfolded beneath painted skies, and the Queen’s own presence often served as the climax of the spectacle.

Yet masques, for all their splendour, remained elite entertainments—confined to the palace walls. Beyond those walls, a different kind of stage was taking shape. Encouraged by the Queen’s occasional patronage and the cautious tolerance of civic authorities, professional theatre companies began to establish permanent playhouses in London.

The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, soon to become the King’s Men, secured royal support—providing a shield against censorship and a license to perform. Their home, the Globe Theatre, would soon become legendary. But before the Globe’s boards echoed with Shakespeare’s verse, the ground had been prepared by decades of poetic and performative experimentation.

Court poets brought their knowledge of myth, allegory, and rhetorical flourish to the emerging world of drama. The skills honed in crafting sonnets and masques found new life on the public stage—where the power of words could move not just noble patrons, but citizens of all ranks.

Actors, too, carried this legacy. Many began their careers performing in court masques before stepping onto the wider public stage. The relationship between courtly and popular performance remained fluid—each feeding the other’s innovations.

By the final years of Elizabeth’s reign, the transformation was nearly complete. Poetry, once the preserve of the court and the printed page, had found a new home: the living, breathing space of the theatre, where verse could speak to the hearts of thousands.

As we close this first scroll of England’s Golden Age and Gathering Shadows, we stand at the threshold of this great shift. The next act belongs to the stage—to Shakespeare and his fellow playwrights, whose words would soon ring through London’s streets and across the centuries.

From the Desk of ABS, The Literary Professor

“Before the players took their marks upon the stage, the poets had already played their parts—in chambers where verses courted favour, and in pages where England itself was being imagined anew.”

In tracing the life of poetry at Elizabeth’s court, we witness more than a parade of glittering names or a catalogue of forms. We glimpse an age when the pen was a tool of diplomacy, desire, and discovery; when poets and patrons alike conspired to craft not only art, but identity.

Sidney’s noble yearning, Spenser’s mythic vision, Raleigh’s restless ambition, and the myriad voices beyond them—each shaped the English Renaissance in ways that would ripple far beyond their own times. And around them moved the unseen hands of women, the presses of London, and the rising hum of the theatre.

In this interplay of word and power, public and private, England forged a literary culture of extraordinary vitality—one whose echoes still sound in our own age.

As we turn to the next scroll, the poets will give way to the playwrights. The stage will rise; the crowds will gather; the words will fly louder and farther.

But let us not forget where it began: in the quiet scratch of a quill upon parchment, beneath the watchful gaze of a Queen who knew, perhaps better than any ruler before her, that words could rule as surely as crowns.

Signed:

From the Desk of ABS, The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance