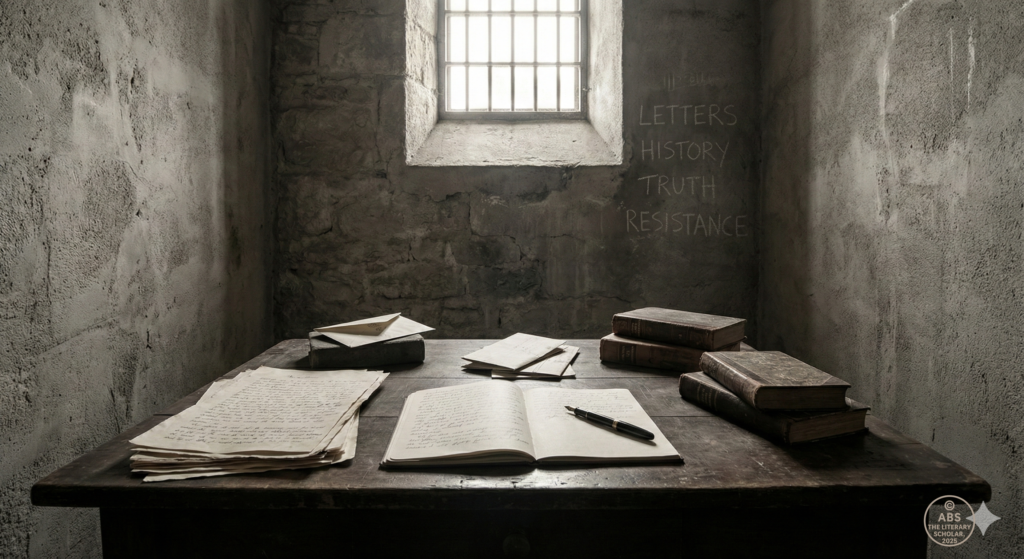

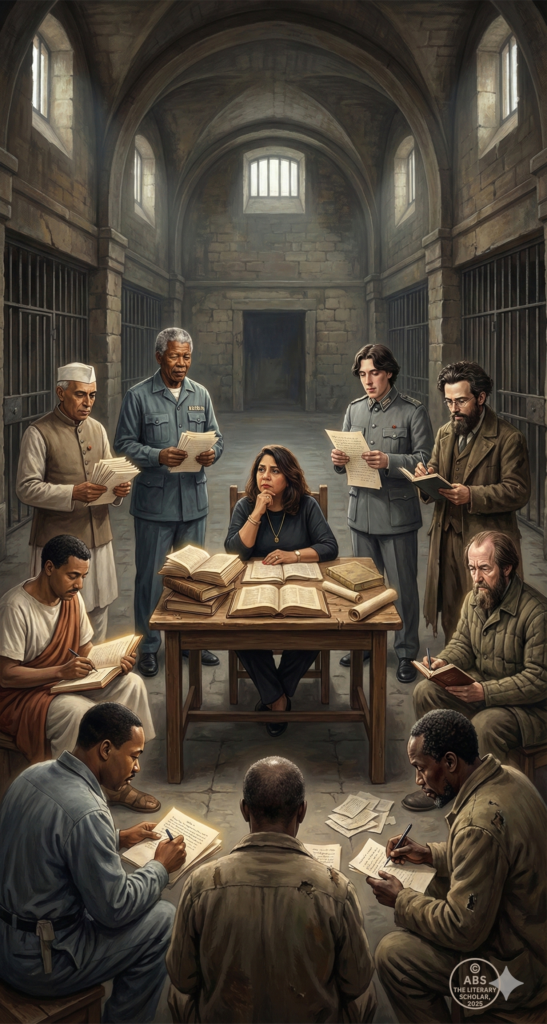

Locked Rooms and Loud Minds

Literature Written When the Body Was Confined and the Mind Refused to Be How confinement shaped political thought, personal truth, and literary resistance

ABS BELIEF

When writers are imprisoned, literature stops entertaining and starts testifying.

1. Jawaharlal Nehru (India)

Imprisonment: 1922–1945 (multiple terms under British rule)

Prison Writing: Glimpses of World History, Letters from a Father to His Daughter

Scroll Title Given:

“History Written Between Lockups”

2. Nelson Mandela (South Africa)

Imprisonment: 1962–1990 (27 years, Robben Island and others)

Prison Writing: Long Walk to Freedom (conceived and partly written in prison)

Scroll Title Given:

“Freedom Drafted Behind Bars”

3. Oscar Wilde (Ireland / Britain)

Imprisonment: 1895–1897 (Reading Gaol)

Prison Writing: De Profundis, The Ballad of Reading Gaol

Scroll Title Given:

“When Wit Was Stripped and Truth Remained”

4. Antonio Gramsci (Italy)

Imprisonment: 1926–1937 (Fascist regime)

Prison Writing: Prison Notebooks

Scroll Title Given:

“Thinking Under Surveillance”

5. Fyodor Dostoevsky (Russia)

Imprisonment: 1849–1854 (Siberian labor camp)

Prison Writing: Notes from the House of the Dead

Scroll Title Given:

“The Birth of Psychological Truth in Chains”

6. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (Russia)

Imprisonment: 1945–1953 (Gulag camps)

Prison Writing: The Gulag Archipelago (based on prison experience)

Scroll Title Given:

“Literature as an Indictment”

7. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (Kenya)

Imprisonment: 1977–1978 (Kamiti Maximum Security Prison)

Prison Writing: Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary, Devil on the Cross

Scroll Title Given:

“Writing When Paper Was a Crime”

8. Jean Genet (France)

Imprisonment: 1940s (multiple terms for theft and vagrancy)

Prison Writing: Our Lady of the Flowers

Scroll Title Given:

“Criminality Turned into Literature”

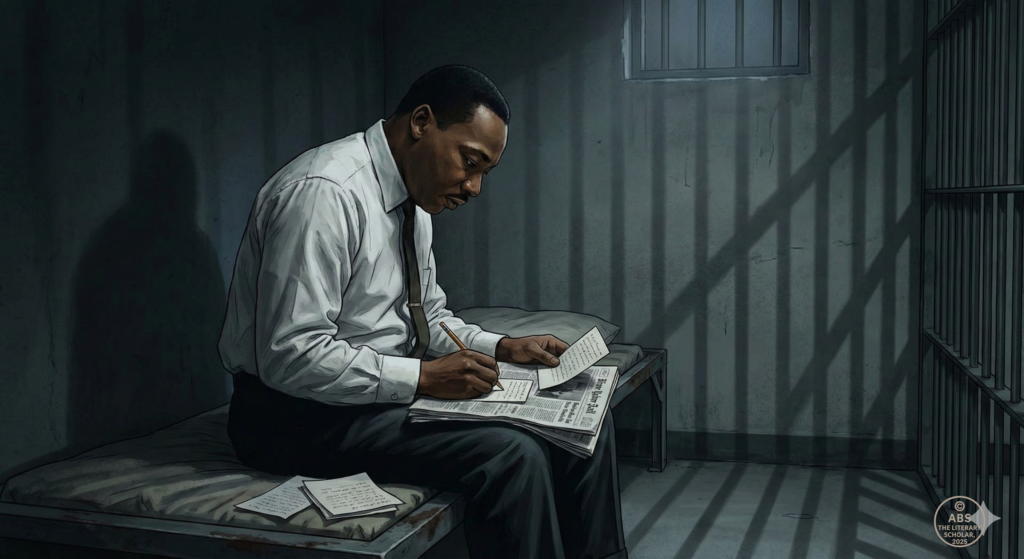

9. Martin Luther King Jr. (United States)

Imprisonment: 1963 (Birmingham Jail)

Prison Writing: Letter from Birmingham Jail

Scroll Title Given:

“A Moral Argument Written in a Cell”

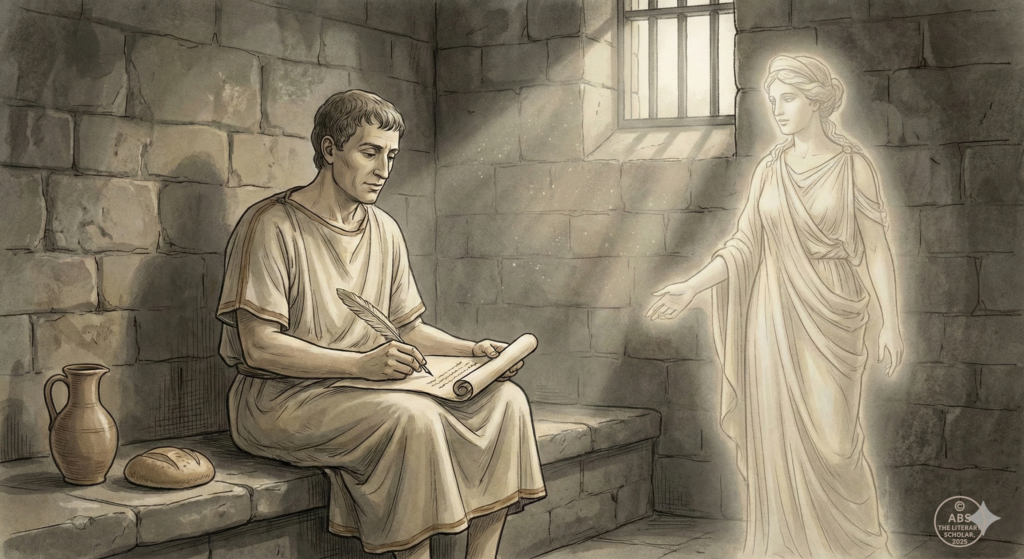

10. Boethius (Roman philosopher)

Imprisonment: c. 523–524 CE (awaiting execution)

Prison Writing: The Consolation of Philosophy

Scroll Title Given:

“Philosophy’s Last Conversation with Freedom”

Literature Written from Prison

This scroll is not about suffering as spectacle.

It is about writing produced under conditions where comfort, privacy, and choice were deliberately removed.

Prison literature exists because silence was imposed and thinking became unavoidable. When writers are confined, they lose access to libraries, desks, publishers, and audiences. What remains is the mind and whatever discipline it can summon. The result is a body of literature that is unusually direct, intellectually rigorous, and resistant to ornament.

Not all prison writing is fiction. Much of it is letters, notebooks, memoirs, philosophical reflections, political arguments, and unfinished drafts. Some texts were written on scraps of paper, some memorised because paper was denied, some smuggled out line by line, and some reconstructed years later from memory. What unites them is not genre, but circumstance.

This scroll focuses on literature written from prison, not metaphorical imprisonment, not exile, not emotional confinement. The writers discussed here were physically incarcerated by states, regimes, or legal systems. Their writing emerged from cells, labor camps, or long-term confinement, often under surveillance.

Political leaders such as Jawaharlal Nehru and Nelson Mandela used prison time to educate future generations and clarify the moral foundations of governance. Thinkers like Antonio Gramsci and Boethius reorganised philosophy itself while cut off from public life. Writers such as Oscar Wilde, Jean Genet, and Fyodor Dostoevsky confronted humiliation, criminality, and psychological extremity without the protection of social status. Others, like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, turned prison writing into acts of resistance, documentation, and survival. In the American context, Martin Luther King Jr. transformed a jail cell into a site of moral argument that continues to shape political thought.

These works do not seek sympathy. They seek accuracy.

They do not persuade through rhetoric alone, but through the authority of lived constraint. Prison removes performance. It leaves testimony.

This scroll examines how confinement reshaped language, sharpened thought, and forced writers to abandon literary comfort in favour of intellectual necessity. It is not a celebration of imprisonment. It is an examination of what writing becomes when freedom is taken away and honesty is no longer optional.

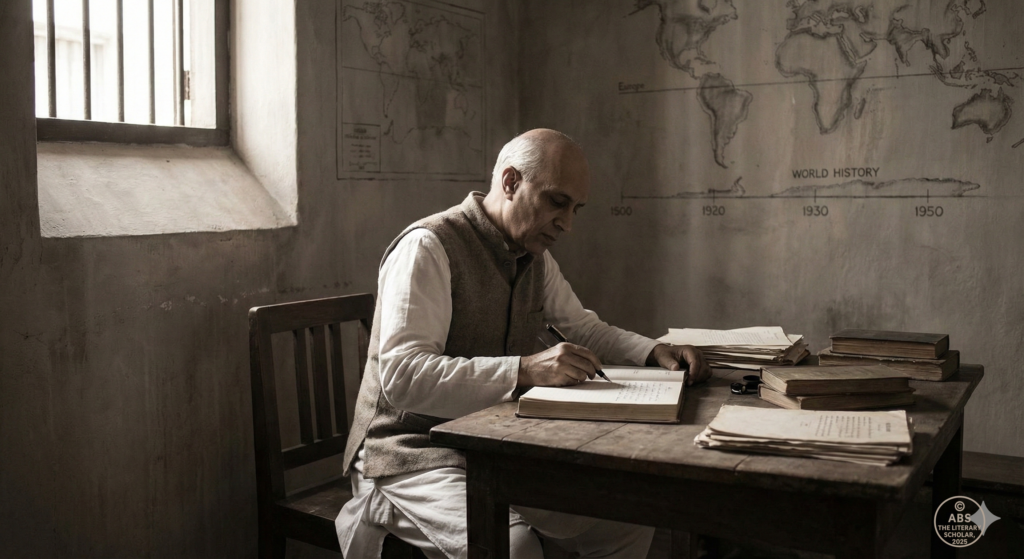

AUTHOR 1

Jawaharlal Nehru

History Written Between Prison Walls

WRITTEN CONTENT

Jawaharlal Nehru did not write from prison as a victim. He wrote as a teacher who had been forcibly given time.

Between 1922 and 1945, Nehru spent nearly a decade in British prisons. These were not brief detentions but extended periods of isolation designed to interrupt political momentum. Instead, they created the conditions for deep intellectual work. Removed from immediate action, Nehru turned to reflection, study, and explanation.

“A jail is strangely a very good place to think.”

In prison, Nehru wrote Glimpses of World History and Letters from a Father to His Daughter, works that resist easy categorisation. They are neither political manifestos nor personal memoirs. They are structured lessons. Addressed to his daughter, they quietly expand into a broader pedagogical project, educating a future generation about history, civilisation, and ethical responsibility.

“Culture is the widening of the mind and of the spirit.”

What distinguishes Nehru’s prison writing is its refusal to collapse into grievance. There is no melodrama, no bitterness directed at his captors. Instead, he insists on context. Empires rise and fall. Civilisations influence one another. History is larger than any single jail cell. Prison restricts movement, but it cannot limit historical imagination.

“The present is not intelligible without the past.”

This distance is deliberate. Nehru understood that leadership demanded perspective rather than reaction. Prison became a space where he could step back from immediate struggle and articulate the intellectual foundations of governance itself. His writing from prison prepares rather than protests.

“A leader or a people without a sense of history is like a tree without roots.”

Nehru’s prison literature demonstrates that confinement does not always produce radicalism or despair. It can also produce clarity. By stripping away public performance and political urgency, prison allowed Nehru to write with calm authority. These texts are acts of nation-building carried out in isolation, proof that literature written from prison can educate, stabilise, and imagine the future.

AUTHOR 2

Nelson Mandela

Freedom Imagined from a Prison Island

Nelson Mandela did not write from prison to document suffering. He wrote to discipline power.

From 1962 to 1990, Mandela spent twenty-seven years in prison, much of it on Robben Island, under conditions designed to break political will through monotony, isolation, and enforced insignificance. Hard labour, censorship, and surveillance were routine. Writing materials were restricted. Letters were cut, delayed, and edited. Memory became a crucial tool.

“Prison itself is a tremendous education in the need for patience and perseverance.”

Much of Long Walk to Freedom was conceived during imprisonment, written in fragments, hidden, memorised, and later reconstructed. The book is not a prison memoir in the narrow sense. It is a political autobiography shaped by confinement, where leadership is refined rather than inflamed.

What distinguishes Mandela’s prison writing is restraint. There is no indulgence in hatred, no rhetorical revenge against the jailor. Prison taught him that anger narrows vision, while discipline expands it. His writing reflects this internal training. The voice remains measured even when describing brutality. The goal is not accusation, but moral positioning.

“I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it.”

Mandela used prison time to study. He read history, politics, and law. He observed men under pressure. He learned how power behaves when it believes it is unobserved. Robben Island became a political classroom where leadership was tested daily, not in speeches, but in silence, routine, and endurance.

“A man who takes away another man’s freedom is a prisoner of hatred.”

Prison writing, for Mandela, was preparation. He was not writing for publication alone, but for a future moment when reconciliation would require authority without vengeance. His language avoids spectacle because spectacle would weaken the argument he was ultimately building: that justice without humanity reproduces tyranny.

“Freedom cannot be achieved unless the women have been emancipated from all forms of oppression.”

By the time Mandela walked free, his ideas had already been rehearsed in confinement. Prison had removed the temptation of popularity and replaced it with moral clarity. His writing from prison demonstrates how literature produced under extreme constraint can shape national conscience rather than merely record injustice.

Mandela’s prison literature stands as evidence that incarceration can refine leadership instead of distorting it. The cell did not silence him. It disciplined him.

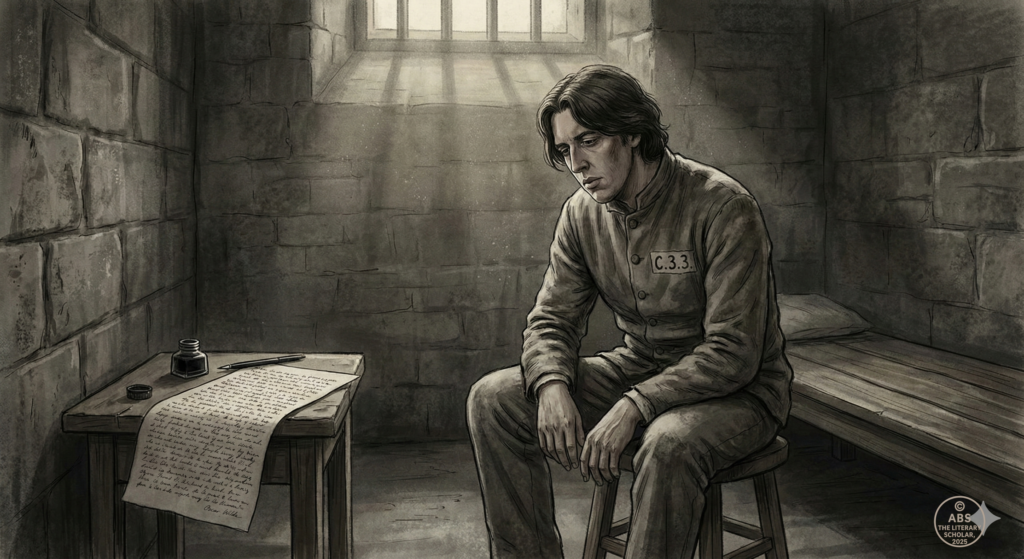

AUTHOR 3

Oscar Wilde

When Wit Was Stripped and Truth Remained

Oscar Wilde went to prison as a celebrity and came out as a human being.

In 1895, Wilde was sentenced to two years of hard labour in Reading Gaol for “gross indecency.” Victorian society did not merely punish him legally; it erased him socially. Prison was designed to humiliate, silence, and reduce him. For a writer whose identity had been built on brilliance, performance, and applause, the punishment was surgical.

“I was a man who stood in symbolic relations to the art and culture of my age.”

In prison, Wilde was stripped of everything that had sustained his public persona. No salons. No audience. No epigrams tossed for laughter. What remained was pain, isolation, and the slow confrontation with the self. Out of this came De Profundis, a long letter written to Lord Alfred Douglas, composed under strict supervision, censored, and never intended as a literary showpiece.

De Profundis is not polished prose. It is uneven, repetitive, raw. That is precisely its power. Wilde abandons performance and writes from collapse. He reflects on love, betrayal, pride, suffering, and the cost of self-deception.

“Where there is sorrow, there is holy ground.”

Prison taught Wilde a language he had never needed before: the language of endurance. Suffering, which he had once aestheticised, now demanded honesty. He does not ask for sympathy. He asks for understanding. He recognises his own vanity, his illusions about love, and his blindness to consequence.

“I did not know that to be shallow one has to be so profound.”

After his release, Wilde wrote The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a poem that shifts attention away from himself toward the collective cruelty of the prison system. The famous line does not moralise; it indicts quietly.

“Yet each man kills the thing he loves.”

This is prison literature at its most devastating: not angry, not revolutionary, but clear. Wilde understands that punishment dehumanises both the punished and the punisher. The poem exposes the machinery of incarceration without rhetoric, relying instead on observation and shared vulnerability.

Oscar Wilde’s prison writing marks a radical transformation. The dandy disappears. The witness remains. His work from prison proves that literature written under humiliation can reach a moral depth inaccessible to comfort. Wit dies in the cell. Truth survives.

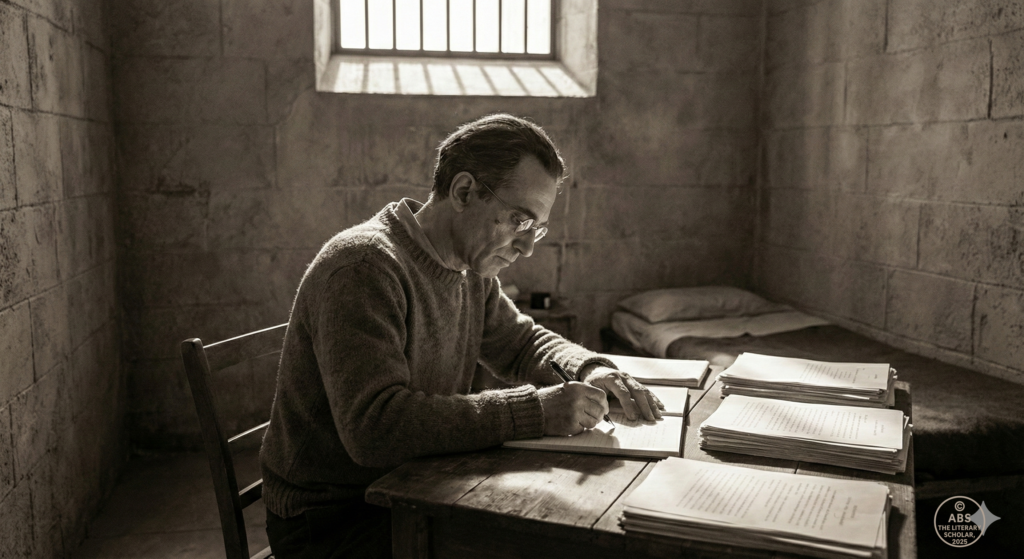

AUTHOR 4

Antonio Gramsci (Italy)

Thinking Under Surveillance

Antonio Gramsci was imprisoned not to punish his body, but to silence his mind.

In 1926, the Fascist regime under Mussolini arrested Gramsci, a Marxist thinker and founding member of the Italian Communist Party. At his trial, the prosecutor famously declared: “We must stop this brain from functioning for twenty years.” What followed instead was one of the most rigorous intellectual projects ever produced behind bars.

“The challenge of modernity is to live without illusions and without becoming disillusioned.”

From 1926 until his death in 1937, Gramsci lived under constant surveillance, censorship, and severe ill health. He was denied proper medical care, access to books was restricted, and writing was monitored. Direct political commentary was dangerous. As a result, Gramsci invented a new method of thinking under constraint.

The Prison Notebooks are not a single book but a fragmented intellectual archive. Written cautiously, often indirectly, they explore culture, power, language, education, folklore, history, and ideology. Gramsci replaces slogans with analysis. Revolution becomes reflection.

“Every relationship of ‘hegemony’ is necessarily an educational relationship.”

Prison forces Gramsci to rethink power not as brute force alone, but as consent manufactured through culture. His concept of cultural hegemony emerges precisely because overt resistance is impossible. When action is blocked, theory deepens.

“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.”

Gramsci’s prison writing is slow, careful, and deliberately unfinished. Ideas are tested, abandoned, revised. This is thinking stripped of certainty. Prison does not give him answers; it sharpens his questions. He writes not to persuade a crowd, but to understand systems that operate invisibly.

“Instruction is only useful when it becomes education.”

Unlike revolutionary manifestos written in freedom, the Prison Notebooks refuse immediacy. They demand patience. Their power lies in endurance. Gramsci understood that regimes fall, but ideas embedded in culture outlast governments.

Antonio Gramsci’s prison literature demonstrates how confinement can transform political urgency into intellectual permanence. Surveillance forced subtlety. Silence forced depth. His writing from prison remains one of the clearest examples of how thought survives when speech is controlled.

AUTHOR 5

Fyodor Dostoevsky (Russia)

The Birth of Psychological Truth in Chains

Fyodor Dostoevsky went to prison a radical intellectual. He came out a psychologist of the human soul.

In 1849, Dostoevsky was arrested for his involvement with the Petrashevsky Circle, a group discussing banned political ideas. He was sentenced to death, taken to the execution ground, and only at the final moment was the sentence commuted to four years of hard labour in a Siberian prison camp, followed by military service. The trauma was not symbolic. It was lived in real time.

“The degree of civilisation in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.”

Siberian imprisonment exposed Dostoevsky to criminals, peasants, murderers, thieves, and political prisoners living under brutal conditions. Disease, filth, humiliation, and violence were constant. Yet it was here that Dostoevsky encountered humanity in its rawest form, stripped of ideology and social pretence.

Years later, he transformed this experience into Notes from the House of the Dead, a work that resists classification. It is neither memoir nor novel, but something in between. The narrative avoids heroic suffering and focuses instead on the daily psychology of confinement: boredom, cruelty, small kindnesses, pride, despair, and the fragile persistence of hope.

“Man is a creature who can get accustomed to anything.”

Prison taught Dostoevsky that suffering does not automatically ennoble. Some prisoners are brutalised beyond repair. Others cling to dignity in absurdly small ways. What emerges is not a moral lesson, but an understanding of contradiction. Human beings are capable of compassion and cruelty simultaneously.

“It is not by confining the body that one can imprison the soul.”

Unlike later prison writers who indict systems directly, Dostoevsky examines inner landscapes. His interest lies in how confinement alters consciousness. Time stretches. Memory distorts. Identity fractures. These observations become the foundation of his later novels, from Crime and Punishment to The Brothers Karamazov.

“Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart.”

Dostoevsky’s prison writing marks the moment literature turns inward with unprecedented intensity. The modern psychological novel is born not in freedom, but in chains. His experience proves that prison literature can generate not only protest or testimony, but entirely new ways of understanding the human mind.

AUTHOR 6

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (Russia)

Literature as an Indictment

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote from prison not to interpret suffering, but to document a crime.

In 1945, Solzhenitsyn was arrested for criticising Stalin in private letters. The punishment was severe: eight years in Soviet labor camps, followed by internal exile. The Gulag was not a metaphor. It was a system. Vast, bureaucratic, methodical. Designed not only to punish bodies, but to erase memory.

“The line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

In the camps, writing openly was impossible. Paper was scarce. Surveillance was constant. Solzhenitsyn learned to compose entire chapters in his head, memorising them through rhythm and repetition. Literature survived by becoming internal. Memory replaced manuscript.

“Literature that is not the breath of contemporary society dares not call itself literature.”

Years later, this mental archive became The Gulag Archipelago, a work that defies genre. It is history, testimony, sociology, memoir, and moral inquiry at once. Solzhenitsyn does not romanticise suffering. He catalogues it. Names it. Counts it. He exposes the machinery of repression with relentless precision.

“One word of truth outweighs the whole world.”

What makes Solzhenitsyn’s prison writing distinct is its refusal to limit guilt to a single villain. He indicts systems, bureaucracies, informers, silence, fear, and complicity. Prison taught him that tyranny survives not only through violence, but through obedience and forgetting.

“The simple step of a courageous individual is not to take part in the lie.”

Unlike Dostoevsky, who explores inner psychology, Solzhenitsyn widens the lens. His writing insists that private suffering has public meaning. The camp is not an aberration. It is the logical outcome of unchecked power.

“You can resolve to live your life with integrity. Let your credo be this: Let the lie come into the world, even dominate the world, but not through me.”

Solzhenitsyn’s prison literature transformed personal survival into historical record. It forced a nation, and then the world, to confront truths that had been systematically buried. His work demonstrates the most confrontational function of prison writing: not consolation, not reflection, but accusation.

This is literature that does not ask to be admired.

It demands to be believed.

AUTHOR 7

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (Kenya)

Writing When Paper Was a Crime

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was imprisoned not for violence, but for language.

In 1977, Ngũgĩ was detained without trial by the Kenyan government and held at Kamiti Maximum Security Prison. His offence was cultural: he had written and staged a politically critical play in Gikuyu, the language of the people, rather than English. For the postcolonial state, this was intolerable. Control of power required control of language.

“Language carries culture, and culture carries the entire body of values by which we come to perceive ourselves and our place in the world.”

In prison, Ngũgĩ was denied writing materials. Paper itself became contraband. Surveillance was constant. Silence was enforced. In response, Ngũgĩ did something radical: he wrote a novel anyway. Using scraps of toilet paper and memorisation, he composed Devil on the Cross, the first modern novel written in Gikuyu.

“The choice of language is the choice of a world.”

Ngũgĩ also kept a prison journal that later became Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary, a text that documents not only incarceration, but the psychology of state repression. Unlike earlier prison writers who focus on personal suffering, Ngũgĩ exposes how prisons function as tools of cultural silencing. The goal is not just to imprison bodies, but to discipline imagination.

“The bullet was the means of the physical subjugation. Language was the means of the spiritual subjugation.”

Prison sharpened Ngũgĩ’s understanding of colonial afterlives. Independence, he realised, had not dismantled systems of control. It had merely changed their managers. Writing in an African language inside a colonial-style prison became an act of resistance more dangerous than protest.

“Prison is not just a place. It is a political condition.”

Ngũgĩ’s prison literature insists that freedom is inseparable from cultural self-definition. By choosing to write in Gikuyu under extreme constraint, he reclaimed narrative authority. Prison could restrict his body, but it could not determine the language of his thought.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s prison writing expands the scope of prison literature beyond individual survival. It becomes a battle over memory, identity, and who gets to speak. When paper was criminal, writing itself became rebellion.

AUTHOR 8

Jean Genet

Criminality Turned into Literature

Jean Genet did not enter prison by accident. He entered it repeatedly. Theft, vagrancy, forgery. Prison was not an interruption in his life. It was its grammar.

Throughout the 1940s, Genet spent long periods in French prisons. Unlike political prisoners, he had no public cause to defend and no moral high ground to claim. Society did not see him as unjustly imprisoned. It saw him as disposable. That is precisely where his literature begins.

“I decided to be what crime made me.”

Genet wrote Our Lady of the Flowers in prison, much of it on scrap paper, under constant surveillance. The novel is not a confession and not a plea for reform. It is an aesthetic transformation of criminal life. Thieves, pimps, murderers, and outcasts are not explained away or redeemed. They are elevated, stylised, mythologised.

“What is called obscenity is often merely the name given to truth by those who fear it.”

Prison, for Genet, is not a place of moral correction. It is a space where identity hardens. Cut off from respectable society, he rejects its values entirely. Shame becomes power. Criminality becomes authorship. He writes from inside the cell not to escape it, but to claim it as origin.

“I wanted to be a writer, but first I had to be a criminal.”

Genet’s prison writing is unsettling because it refuses the usual narrative of suffering leading to virtue. There is no repentance here. There is defiance. His language is lush, erotic, ritualistic. Beauty is deliberately wrested from what society calls filth. Prison becomes a theatre where identity is performed with brutal honesty.

“To write was to refuse rehabilitation.”

Unlike Wilde, who is broken by humiliation, Genet weaponises it. Prison does not humble him. It sharpens him. His work exposes how institutions create the very deviance they claim to punish, and how literature can emerge from absolute exclusion.

Jean Genet’s prison literature expands the boundaries of what prison writing can be. It is not testimonial. It is not moral instruction. It is radical self-fashioning. His work forces readers to confront an uncomfortable truth: some voices do not seek forgiveness. They seek recognition.

AUTHOR 9

Martin Luther King Jr. (United States)

A Moral Argument Written in a Cell

Martin Luther King Jr. did not write from prison as a criminal or a revolutionary.

He wrote as a moral witness answering an accusation.

In April 1963, King was arrested during the Birmingham Campaign and held in Birmingham City Jail. Unlike long-term imprisonment, this confinement was brief. Its significance lies not in duration, but in precision. From a narrow cell, denied books and reference materials, King wrote one of the most influential political texts of the twentieth century: Letter from Birmingham Jail.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

The letter was a response to white clergymen who criticised civil rights protests as “untimely” and “extreme.” Writing on scraps of paper, newspaper margins, and smuggled notes, King constructs a disciplined moral argument. There is no rage here. No improvisation. Prison sharpens his logic rather than inflaming his tone.

“Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

King uses the jail cell as a courtroom. He defines just and unjust laws, exposes the moral bankruptcy of gradualism, and reclaims civil disobedience as ethical necessity. Prison does not silence him; it provides the vantage point from which hypocrisy becomes unmistakable.

“An unjust law is no law at all.”

What makes King’s prison writing distinct is its balance of urgency and restraint. He writes not only for supporters, but for opponents. The letter assumes the intelligence of its reader. It persuades through reason, history, theology, and lived experience, not slogans.

“We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor.”

Unlike other prison writers who explore suffering or survival, King’s focus is responsibility. He insists that moral clarity demands action, even when consequences are severe. Jail becomes proof of commitment rather than evidence of deviance.

“Justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

Letter from Birmingham Jail demonstrates how prison literature can function as public conscience. Written under constraint, without access to sources, it remains one of the clearest articulations of ethical resistance. King’s cell becomes a site where law is measured against justice and found wanting.

This is prison writing at its most disciplined: argument without bitterness, resistance without hatred, and conviction without spectacle.

AUTHOR 10

Boethius (Roman philosopher)

Philosophy’s Last Conversation with Freedom

Boethius wrote from prison knowing he would not leave it alive.

In around 523–524 CE, Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, a Roman senator and philosopher, was imprisoned on charges of treason under the Ostrogothic king Theodoric. Stripped of office, status, and protection, he awaited execution. There was no appeal, no audience, no future to plan for. What remained was thought.

“In every adversity of fortune, the most unhappy kind is once to have been happy.”

While awaiting death, Boethius composed The Consolation of Philosophy, one of the most influential prison texts in Western intellectual history. Written as a dialogue between himself and Lady Philosophy, the work refuses despair. It interrogates it.

“Fortune’s favors are always uncertain.”

Unlike later prison writers who indict systems or document cruelty, Boethius turns inward. He asks timeless questions: What is happiness? What is justice? Does suffering negate meaning? If fortune is unstable, where should human beings anchor their lives?

“Nothing is miserable unless you think it so.”

Prison forces Boethius to confront the collapse of external identity. Power, reputation, wealth, and honour vanish overnight. Philosophy becomes not an academic exercise, but a survival mechanism. Writing is not resistance here; it is reconciliation with mortality.

“He who is at peace with himself fears no external misfortune.”

What makes Boethius’s prison writing extraordinary is its calm. Facing execution, he does not curse fate or plead innocence. Instead, he disciplines grief through reason. The prison cell becomes a final classroom, where philosophy is tested against extinction.

“The mind that is fixed on God is free, even in chains.”

The Consolation of Philosophy shaped medieval thought for centuries, influencing figures from Dante to Chaucer. It proves that prison literature is not only a product of modern political repression. It is one of civilisation’s oldest intellectual responses to confinement.

Boethius shows us prison writing at its most elemental: no protest, no witness, no audience—only a human mind arguing with despair and refusing to surrender its dignity.

This is not literature written to survive prison.

It is literature written to survive death.

What Prison Writing Ultimately Reveals

Across centuries, continents, ideologies, and languages, the ten writers explored in this scroll demonstrate one unsettling truth: prison does not destroy literature; it exposes it.

These authors did not share a common politics, temperament, or literary style. Nehru wrote as a historian and educator. Mandela wrote as a disciplined statesman in preparation. Wilde wrote from collapse and humiliation. Genet wrote from defiance and criminal identity. Gramsci wrote under surveillance, thinking in fragments. Dostoevsky wrote from trauma that restructured his understanding of the human soul. Solzhenitsyn wrote to indict a system built on silence. Ngũgĩ wrote to reclaim language itself. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote to hold law accountable to justice. Boethius wrote to argue with despair in the face of death.

What unites them is not suffering, but constraint.

Prison removes performance. It strips away audience, reward, and literary vanity. There are no book launches in a cell, no applause, no reputations to protect. Writing becomes necessity rather than ambition. As a result, prison literature rarely lies. It may argue, confess, accuse, or philosophise, but it does not flatter.

Another striking pattern emerges: prison writing refuses simplification. None of these authors reduce oppression to a single villain or salvation to a single idea. Even Solzhenitsyn insists on moral complexity. Even King balances urgency with restraint. Even Wilde implicates himself. Prison sharpens thought because it punishes excess—of ego, rhetoric, and illusion.

These texts also reveal that incarceration targets more than bodies. It targets memory, language, and continuity. That is why writing becomes resistance. Whether on toilet paper, in memorised lines, in censored notebooks, or in philosophical dialogue, these writers understood that to write is to refuse erasure.

Finally, prison literature forces readers to confront an uncomfortable reality: many of the most durable ideas in human history were produced not in comfort, but in confinement. Not because suffering is ennobling, but because constraint demands honesty.

Literature written from prison is not a genre of despair.

It is a record of what remains when everything else is taken away.

ABS Closes the Scroll

ABS, the literary scholar, pauses longer than usual. Astonishment settles first, then a quiet weight. Literature created under comfort already demands discipline. Literature created under punishment demands something rarer: courage without witnesses.

The mind lingers on the difficulty of confinement. Closed doors. Regulated breath. Days measured by commands rather than clocks. From such conditions emerged history lessons, moral arguments, philosophical dialogues, psychological truths, and indictments of entire systems. Imagination survived iron. Thought survived surveillance. Language survived deliberate erasure.

ABS recognises the scale of spirit required. Writing under freedom allows delay, revision, indulgence. Writing under incarceration allows none. Each sentence risks punishment. Each page risks confiscation. Each idea risks disappearance. Yet creation continued. Not as defiance alone, but as responsibility. A responsibility to memory, to conscience, to future readers unaware of locked rooms.

Great spirits appear not heroic but exacting. Discipline replaces drama. Clarity replaces ornament. Words carry weight because circumstances permit no excess. A cell becomes a classroom. A bunk becomes a desk. Silence becomes a testing ground for thought. Legacy forms without intention, without comfort, without promise of survival.

ABS feels obligation rather than admiration. Obligation to read carefully. Obligation to write honestly. Obligation to remember that literature does not begin in applause but in necessity. Punishment failed to erase voice. Confinement failed to shrink vision. Power failed to silence thought.

The scroll reaches closure with reverence, not sentiment. Gratitude settles for inheritance received through sacrifice. Legacy stands intact because courage chose language over surrender. ABS gathers the pages slowly. History remains written. Conscience remains awake. The mind leaves the cell, carrying voices that refused disappearance.

Abha Bhardwaj Sharma is a Professor of English Literature with over 25 years of teaching experience. She is the founder of Miracle English Language and Literature Institute and the author of more than 50 books on literature, language, and self-development. Through The Literary Scholar, she shares insightful, witty, and deeply reflective explorations of world literature.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance