Notice

© 2023, Abha Bhardwaj Sharma

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

This study material is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. The publisher has strived to ensure that all information in this book is correct at the time of publication and accepts no responsibility for any inaccuracies or errors.

Please note that the information and materials used in this book are strictly for educational purposes. They have been carefully selected and modified to align with the curriculum. While many are original works, some have been sourced from public domain, news outlets, online magazines/newspapers, and other resources. Any third- party content is used for illustrative or educational purposes and the copyright rests with the original creator/publisher. These are utilised with the intent to provide a diverse and enriching learning experience for the students. The source list is available with the institute. While efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, the author/ publisher is not liable for any inaccuracies or for the use of this information.

For permission requests, contact us on our website, www.miraclejaipur.com.

Address: Miracle English Language and Literature Institute

Jaipur, Rajasthan, 302001

+91-9829121892

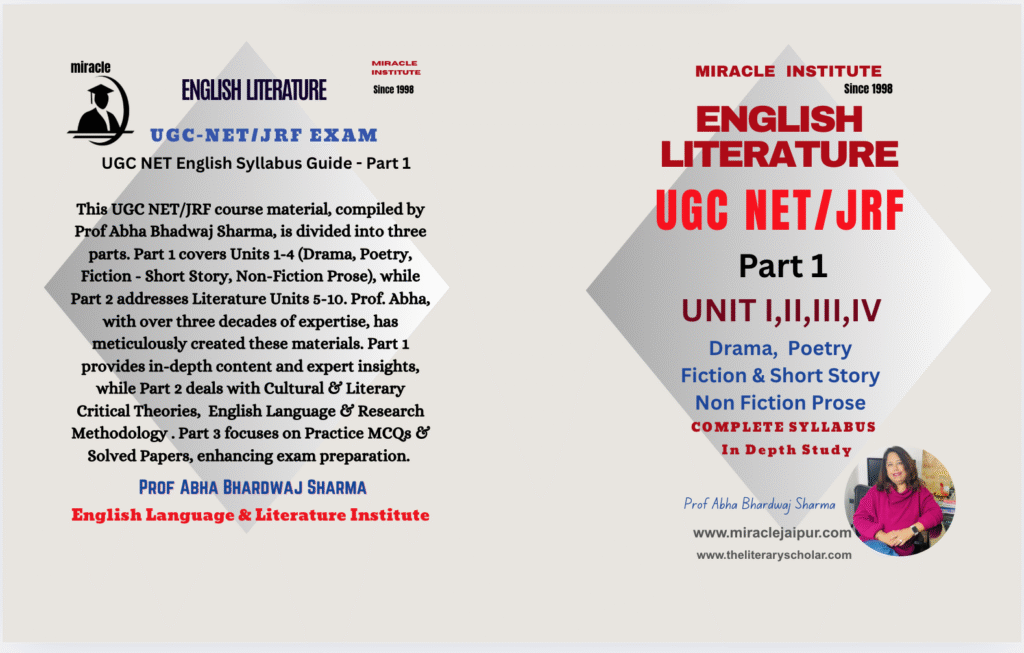

UGC NET/JRF Course Material: in Three Parts

Part 1 Units 1-4

Part 2 Units 5-10

Part 3 Practice MCQs & Solved Papers

Compiled by Prof Abha Bhardwaj Sharma.

Effective and comprehensive study material is essential for students preparing for competitive examinations like UGC NET/JRF. Prof Abha Bhardwaj Sharma’s rich study material is thoughtfully curated to provide students with a structured and reliable foundation for their studies. The material is meticulously designed to cover the core concepts, theories, and key topics in each of the units in both pats

Prof Abha Bhardwaj Sharma is a distinguished expert in the fields of Language, Literature, and Linguistics, with a remarkable professional journey spanning over three decades. Her dedication to the realms of education and scholarship is further exemplified by her ownership of the esteemed Miracle English Language and Literature Institute, a renowned institution since its establishment in 1998. Prof Abha’s illustrious career has seen the transformation of numerous students into successful scholars under her guidance.

Key Features of the Study Material Part1 & Part 2

In-Depth Content: The study material extensively explores each literary unit, offering comprehensive coverage of significant literary works, historical contexts, critical analyses, and prominent literary figures. This depth of coverage ensures that students gain a profound understanding of the subject matter, allowing them to engage with the material at an advanced level.

Clarity and Conciseness: The study material is recognised for its remarkable clarity and conciseness, making even the most intricate literary concepts accessible to students with diverse backgrounds and varying levels of expertise. The language and explanations employed are carefully crafted to simplify complex ideas without compromising on the depth of understanding.

Expert Insights: The study material benefits from the inclusion of expert insights that draw from a wealth of experience in the field. These insights offer students valuable perspectives, enabling them to approach literary texts and critical theories with increased confidence and sophistication. By leveraging the expertise embedded in the material, students can develop a more nuanced and informed interpretation of the subject matter.

Updated Content: Recognizing the dynamic nature of the field, the study material is regularly reviewed and updated to align with the evolving trends in literary studies and the UGC NET/JRF syllabus. This commitment to staying current ensures that students receive the most up-to-date and relevant information, preparing them effectively for their academic pursuits and examinations.

The above features collectively make the study material a comprehensive and indispensable resource for students aiming to excel in their literary studies and UGC NET/JRF examinations.

Part 3: Practice MCQs & Solved Papers

In addition to the comprehensive coverage of literary units and key concepts in Parts 1 and 2, Part 3 is a valuable component of the study material. This section is dedicated to Practice Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) and Solved Papers.

Practice MCQs: This section includes a wide range of MCQs meticulously designed to challenge students’ understanding of the subject matter. These questions not only assess knowledge but also encourage critical thinking and application of concepts. With varying levels of difficulty, these MCQs serve as an excellent tool for self-assessment and skill enhancement.

Solved Papers: The inclusion of Solved Papers in Part 3 is particularly advantageous for students as they can gain insights into the format and structure of actual UGC NET/JRF examinations. These solved papers provide real-life examples of questions and demonstrate how to approach and solve them effectively. By studying these solved papers, students can build confidence and refine their examination strategies.

Part II

UGC NET/JRF

UNIT : V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X

UNIT V 9

Language : Basic Concepts, Theories and Pedagogy, English in Use

“Language Dynamics:

Concepts, Theories, Pedagogy, and Practical Applications in English”

UNIT VI 55

English in India: History, Evolution, and Future

“From Raj to Renaissance:

The Evolution and Prospects of English in India”

UNIT VII 93

Cultural Studies

“Cultural Studies in Literature:

Exploring the Interplay of Culture, Society, and Texts”

UNIT VIII 157

Literary Criticism

“Between Text and Reader:

A Guide to Literary Criticism”

UNIT IX 217

Literary Theory:Post World War II

Post-World War II Literary Theories and Their Transformative Impact”

UNIT X 270

Research Methodology

“Methodology in Literary Research: Tools and Techniques”

Congratulations on completing the first part of our UGC NET English course, where we delved into Drama, Poetry, Fiction & Short Story, and Non-fictional Prose. This course material has been thoughtfully compiled by the dedicated Prof. Abha, who has invested significant effort into its creation.

As you embark on the next phase, you will explore the remaining six units, including Language Basics, English in India, Cultural Studies, Critical and Literary Theories, and Research Methodology. Each of these units presents a unique opportunity to expand your knowledge in the diverse field of English studies.

We trust that your journey through these upcoming units will be enlightening and enriching. This endeavor is more than just an academic pursuit; it is a chance to broaden your horizons, challenge your perspectives, and engage with a rich tapestry of ideas that characterize the world of English studies.

With your dedication and thirst for knowledge, you are poised for success in your academic pursuits. Keep in mind that learning is an ongoing voyage, and each unit in this course is a stepping stone toward your continuous growth and development. Approach this opportunity with enthusiasm, and may the knowledge you acquire serve you well in all your future aspirations.

Here’s to your ongoing journey of learning, exploration, and success in the captivating realm of English language and literature.

UGC NET /JRF

UNIT V

Language : Basic Concepts,

Theories and Pedagogy, English in Use

“Language Dynamics:

Concepts, Theories, Pedagogy, and Practical Applications in English”

Content

Language:

Definition and Key Components

Phonetics:

Study of Speech Sounds

Vowels and Consonants:

Types of Speech Sounds

Vowels and Vowel Sounds:

Articulation and Examples

Table of Vowels:

Short, Long, and Diphthong Vowels

Table of Consonants:

Voiceless and Voiced Consonants

Morphology:

Study of Word Structure

Syntax:

Sentence Structure and Grammar

Semantics:

Meaning in Language

Dialects:

Variations of a Language

Grammar:

Rules of Sentence and Word Structure

Bilingualism and Multilingualism:

Speaking Multiple Languages

Theories of Language:

Chomsky’s Universal Grammar

Skinner’s Behaviorist Theory

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory

Pedagogy:

Language Acquisition and Teaching Methods

Language Teaching Approaches:

Communicative Approach

Grammar-Translation Method

Immersion

Assessment:

Methods for Evaluating Language Proficiency

English in Use:

Practical Application in Real-Life Situations

Language Skills:

Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing

Language Varieties:

British English, American English, Global Varieties

Language Learning Resources:

Books, Courses, and Online Materials

Language Learning Apps:

Duolingo, Memrise, Rosetta Stone, and Others

Language Exchange:

Partnering with Native Speakers for Practice

Language: Basic Concepts, Theories and Pedagogy, English in Use

Language:

Definition: Language is a complex system of communication that allows humans to convey thoughts, ideas, and emotions through a structured set of symbols, sounds, and gestures.

Key Components: Language typically consists of elements like phonetics (sounds), morphology (word structure), syntax (sentence structure), semantics (meaning), and pragmatics (contextual usage).

Basic Concepts in Language:

Linguistics: The scientific study of language, which includes phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics.

Dialects: Variations of a language that arise due to geographical, social, or cultural factors.

Grammar: Rules governing the structure and formation of sentences and words in a language.

Bilingualism and Multilingualism: The ability to speak and understand multiple languages.

Theories of Language:

Noam Chomsky’s Theory: Chomsky proposed the theory of Universal Grammar, suggesting that humans have an innate capacity for language acquisition.

B.F. Skinner’s Behaviorist Theory: Skinner argued that language development is a result of conditioning and reinforcement.

Sociocultural Theory (Lev Vygotsky): Vygotsky’s theory emphasizes the role of social interactions and cultural context in language development.

Pedagogy:

Language Acquisition: Teaching methods and strategies for learners of all ages to acquire and develop language skills.

Language Teaching Approaches: Various approaches, such as the communicative approach, grammar-translation method, and immersion, are used to teach languages.

Assessment: Methods for evaluating language proficiency, including tests, exams, and performance assessments.

English in Use:

Practical Application: Using the English language in real-life situations, including speaking, writing, listening, and reading.

Language Skills: Focusing on the four language skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing, to become proficient in English.

Language Varieties: Recognizing and using different forms of English, such as British English, American English, and global varieties.

Language Learning Resources:

Books and Courses: Textbooks, language courses, and online resources that provide structured learning materials.

Language Learning Apps: Mobile apps like Duolingo, Memrise, and Rosetta Stone that offer interactive language learning experiences.

Language Exchange: Partnering with native speakers for language exchange to practice speaking and listening skills.

Language is a dynamic and diverse field, and understanding its basic concepts, theories, and pedagogy can be valuable for both language learners and educators. The practical use of English is essential for effective communication in a globalized world. Whether you’re learning or teaching language, it’s important to adapt to the specific needs and goals of the learners.

Language:

The key components:

Phonetics: Phonetics is the study of the physical properties of speech sounds, known as phonemes. It involves the analysis and classification of the sounds produced in human speech. Phonetics is concerned with aspects like articulation (how speech sounds are produced), acoustic properties (the physical characteristics of sound waves), and auditory perception (how sounds are heard and processed by the ear and brain).

Morphology: Morphology is the study of the internal structure of words and how words are formed. It deals with morphemes, which are the smallest units of meaning in a language. Morphemes can be prefixes, suffixes, roots, or whole words. Morphology explores how these elements combine to create meaningful words.

Syntax: Syntax refers to the rules governing the arrangement of words into sentences or phrases in a language. It deals with sentence structure and the relationships between words within sentences. Syntax helps us understand how words are ordered to convey specific meanings and how different word orders can change the meaning of a sentence.

Semantics: Semantics is the study of meaning in language. It focuses on how words, phrases, and sentences convey meaning and how meaning can vary depending on context. Semantic analysis explores the relationships between words and how they combine to create meaningful expressions.

Pragmatics: Pragmatics is concerned with the use of language in context. It examines how people use language to communicate effectively in various social situations. Pragmatics includes aspects like speech acts (how language is used to perform actions like making requests or giving orders), implicature (unspoken communication implied by context), and the influence of cultural and social norms on language use.

Understanding these key components of language is essential for linguists, language learners, and anyone interested in effective communication. Together, they provide a comprehensive framework for analyzing and using language to convey thoughts, ideas, and emotions in a structured and meaningful way.

Phonetics

Phonetics is the branch of linguistics that deals with the study of the physical properties of speech sounds, known as phonemes. Phonemes are the smallest units of sound in a language that can change the meaning of a word. Here are some key aspects of phonetics:

Articulatory Phonetics: This branch of phonetics focuses on how speech sounds are physically produced by the human vocal apparatus. It examines the movements of the tongue, lips, vocal cords, and other articulatory organs during speech. For example, it studies how different sounds are created by varying the placement and manner of articulation.

Acoustic Phonetics: Acoustic phonetics analyzes the physical properties of sound waves produced during speech. It involves the study of aspects such as frequency (pitch), amplitude (loudness), and duration of speech sounds. Acoustic phonetics is concerned with the transmission and reception of speech sounds.

Auditory Phonetics: Auditory phonetics deals with how humans perceive and process speech sounds. It explores the mechanisms of hearing and the brain’s interpretation of sound signals. This branch is essential for understanding how humans recognize and distinguish different phonemes.

Phonetic Transcription: To represent speech sounds accurately, phoneticians use a system of symbols called the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). Phonetic transcription involves using these symbols to transcribe spoken language, providing a visual representation of the sounds used in a word or sentence.

Phonological Rules: Phonetics is closely related to phonology, which deals with the abstract, underlying sound patterns in a language. Phonological rules describe how phonemes are used and combined in a specific language. These rules govern phenomena like assimilation (when sounds become more like neighboring sounds) and elision (the omission of certain sounds in connected speech).

Phonetic Variations: Different languages and dialects have their own unique sets of phonemes and pronunciation patterns. Phonetics helps linguists understand and document these variations. It also plays a crucial role in the study of accent and speech disorders.

Applications: Phonetics has practical applications in fields such as speech therapy, linguistics research, language teaching, and speech recognition technology. It is used to improve pronunciation, develop speech synthesis and recognition systems, and diagnose and treat speech disorders.

Phonetics is a foundational area of study in linguistics and is essential for understanding how humans produce and perceive speech sounds. It provides valuable insights into the diversity of sounds found in languages worldwide and helps researchers and language learners alike in the analysis and improvement of spoken language.

Vowels and Consonants

Vowels and consonants are two fundamental categories of speech sounds in human languages. They play a crucial role in the formation of words and are essential components of language. Here’s an explanation of each:

Vowels:

Definition: Vowels are speech sounds produced without significant constriction or closure in the vocal tract. When you pronounce a vowel, the airflow is relatively unrestricted, and the sound is typically produced with an open configuration of the mouth.

Characteristics: Vowels are characterized by the following features:

Sonority: Vowels are highly sonorous, meaning they have a clear and resonant sound.

Audibility: Vowels are usually the most audible and prominent sounds in a syllable.

Formants: Vowels have prominent formants (resonant frequencies) that distinguish them from one another.

Steady Sound: Vowels are generally produced with a relatively steady and sustained sound.

Examples: In English, some vowel sounds are represented by the letters A, E, I, O, U, as in words like “cat,” “bed,” “bit,” “hot,” and “cup.” However, English has more vowel sounds than vowel letters, so vowel sounds may be represented by various combinations of letters or digraphs (two letters representing one sound).

Consonants:

Definition: Consonants are speech sounds produced with a significant constriction or closure in the vocal tract. This constriction or closure can occur at various points in the mouth, such as the lips, tongue, teeth, or the back of the mouth.

Characteristics: Consonants are characterized by the following features:

Less Sonority: Consonants are generally less sonorous than vowels, which means they have a more obstructed or less resonant sound.

Closure or Narrowing: Consonants involve either complete closure (stops), partial closure (fricatives), or narrowing (approximants) of the vocal tract to produce sound.

Variability: Consonants can exhibit a wide range of variations based on place of articulation, manner of articulation, and voicing (whether the vocal cords vibrate during sound production).

Examples: In English, consonants include sounds represented by letters like B, C, D, F, G, H, J, K, L, M, N, P, Q, R, S, T, V, W, X, Y, and Z. Examples of consonant sounds include /b/ (as in “bat”), /s/ (as in “sit”), /m/ (as in “man”), and /k/ (as in “cat”).

In spoken language, both vowels and consonants are used to form syllables and words. The alternation and combination of these speech sounds are essential for communication. The distinction between vowels and consonants is a fundamental aspect of phonetics and phonology, which are branches of linguistics that study the sounds and patterns of human speech in different languages.

The Sounds

Vowels are speech sounds produced without significant constriction or closure in the vocal tract. Vowel sounds are the most sonorous and acoustically prominent sounds in a language. They are characterized by the following features:

Sonority: Vowels are highly sonorous, meaning they have a clear and resonant sound. This makes them more audible and prominent in spoken language.

Audibility: Vowels are usually the most audible and prominent sounds in a syllable. They provide the “nucleus” of a syllable, around which consonants may cluster.

Formants: Vowels have prominent formants, which are specific frequency bands in the acoustic signal. These formants distinguish different vowel sounds from each other. The first and second formants are especially important in vowel perception.

Open Configuration: Vowels are produced with an open configuration of the vocal tract. This means that the airflow is relatively unrestricted, and there is no significant constriction or closure, allowing the sound to be produced with a relatively steady and sustained tone.

Variety: Languages typically have several vowel sounds, and the number and quality of vowel sounds can vary from one language to another. For example, English has around 15 distinct vowel sounds, which can be short or long, tense or lax, and they vary depending on dialect and accent.

Vowel sounds are often represented in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) with symbols like /i/ (as in “beet”), /e/ (as in “bet”), /a/ (as in “bat”), /o/ (as in “boat”), and /u/ (as in “boot”). The shape of the vocal tract, particularly the position of the tongue, plays a significant role in producing different vowel sounds.

In English, vowels are a critical component of syllables and words. The alternation and combination of vowel sounds, along with consonants, create the rich and varied soundscape of the English language and contribute to its pronunciation and rhythm. Different languages have their own sets of vowel sounds, and the specific characteristics and number of vowel sounds can vary widely among languages.

A table of English vowels, categorised as short vowels, long vowels, and diphthongs:

Short Vowels:

Symbol | Example Words |

/æ/ | cat, bat |

/ɛ/ | bed, red |

/ɪ/ | sit, bit |

/ɒ/ | hot, not |

/ʌ/ | cup, up |

/ʊ/ | book, look |

/ə/ | a/bout, com/ma, so/fa |

Long Vowels:

Symbol | Example Words |

/i:/ | bee, see |

/eɪ/ | day, say |

/aɪ/ | sky, my |

/oʊ/ | go, no |

/u:/ | blue, two |

/ɔɪ/ | boy, toy |

Diphthongs:

Symbol | Example Words |

/eɪ/ | cake, make |

/aɪ/ | time, mine |

/ɔɪ/ | coin, join |

/aʊ/ | now, how |

/əʊ/ | home, bone |

/ju:/ | cute, use |

In this table:

Short vowels are typically found in closed syllables or followed by a consonant, and they are generally pronounced more briefly than long vowels and diphthongs.

Long vowels are usually found in open syllables or before a silent ‘e’ in words, and they are pronounced for a longer duration.

Diphthongs are combinations of two vowel sounds within the same syllable, where the tongue glides or moves from one vowel position to another. They are often found in stressed syllables.

Please note that the actual pronunciation of vowels can vary depending on regional accents and dialects in English. This table provides a general overview of the most common vowel sounds in standard American English pronunciation.

Consonants voiceless and voiced

A table of English consonants categorized as voiceless and voiced:

Voiceless Consonants:

Sound | Example Words |

/p/ | pen, stop |

/t/ | top, cat |

/k/ | kite, back |

/f/ | fish, leaf |

/θ/ | think, both |

/s/ | sit, glass |

/ʃ/ | ship, wish |

/h/ | hat, help |

Voiced Consonants:

Sound | Example Words |

/b/ | big, lab |

/d/ | dog, bed |

/g/ | go, bag |

/v/ | van, love |

/ð/ | this, mother |

/z/ | zoo, rose |

/ʒ/ | measure, vision |

/m/ | man, time |

/n/ | no, dinner |

/ŋ/ | sing, bring |

/l/ | leg, bell |

/r/ | red, car |

/j/ | yes, yellow |

/w/ | wet, one |

In this table:

Voiceless consonants are produced without vibration of the vocal cords. Air flows through a relatively unobstructed vocal tract when producing these sounds.

Voiced consonants are produced with vibration of the vocal cords. When producing these sounds, the vocal cords come together, and air passes through, creating a buzzing or vibration.

Please note that the actual pronunciation of consonants can vary depending on regional accents and dialects in English. This table provides a general overview of the most common consonant sounds in standard American English pronunciation.

Morphology

Morphology is a branch of linguistics that deals with the structure, formation, and analysis of words in a language. It focuses on understanding the smallest units of meaning within a language and how these units combine to form words. Here are some key aspects of morphology:

Morpheme: A morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of language. Morphemes can be words themselves or parts of words, such as prefixes, suffixes, and roots. Morphemes can be further classified into two main types:

Free Morphemes: These are morphemes that can stand alone as words with meaning. For example, in English, “book,” “run,” and “happy” are free morphemes.

Bound Morphemes: Bound morphemes are morphemes that cannot stand alone and must be attached to other morphemes to convey meaning. For example, the “-ed” in “walked” or the “-s” in “cats” are bound morphemes.

Word Formation: Morphology explores how words are formed through the combination of morphemes. Words can be simple, consisting of a single morpheme (e.g., “dog”), or complex, made up of multiple morphemes (e.g., “unhappiness,” consisting of “un-” + “happy” + “-ness”).

Affixation: Affixes are bound morphemes that are added to a base word to create new words or modify the meaning of the base word. There are two main types of affixes:

Prefixes: Added to the beginning of a word (e.g., “un-” in “undo”).

Suffixes: Added to the end of a word (e.g., “-ment” in “enjoyment”).

Inflectional vs. Derivational Morphemes: Morphemes can also be categorized as inflectional or derivational:

Inflectional Morphemes: These morphemes primarily convey grammatical information such as tense, number, case, or degree. In English, common inflectional morphemes include “-ed” (past tense), “-s” (plural), and “-ing” (present participle).

Derivational Morphemes: These morphemes are used to create new words or to change the grammatical category or meaning of a word. For example, adding the derivational suffix “-er” to the verb “teach” creates the noun “teacher.”

Morphological Processes: Morphology also involves various processes, including compounding (combining two or more words to create a new word, e.g., “toothbrush”), blending (combining parts of two words, e.g., “smog” from “smoke” and “fog”), and reduplication (repeating a morpheme or part of it for emphasis or to create a new word, e.g., “boo-boo”).

Morphological Analysis: Linguists use morphological analysis to break down words into their constituent morphemes to understand their structure and meaning. This analysis helps uncover the underlying rules and patterns of word formation in a language.

Morphology is a fundamental aspect of language study because it provides insights into how words are constructed and how meaning is conveyed through word structure. It plays a crucial role in language understanding, word formation, and language acquisition.

Syntax

Syntax is a branch of linguistics that focuses on the structure, organization, and rules governing the arrangement of words and phrases to create meaningful sentences in a language. It is concerned with the principles and patterns that govern sentence formation and the relationships between words and phrases within sentences. Here are some key concepts related to syntax:

Sentence Structure: Syntax examines the hierarchical structure of sentences. Sentences are composed of smaller units, such as phrases and clauses, which, in turn, consist of words. These units are organized in a specific order to convey meaning.

Constituency: In syntax, a constituency refers to a group of words that function as a single unit within a sentence. Constituents can include words, phrases, and clauses. For example, in the sentence “She loves to read books,” “to read books” is a constituent that functions as the direct object of the verb “loves.”

Word Order: Different languages have different word orders, which dictate the arrangement of subject, verb, object, and other elements within a sentence. Common word orders include subject-verb-object (SVO), subject-object-verb (SOV), and verb-subject-object (VSO).

Sentence Types: Syntax also deals with the formation of different sentence types, such as declarative (statements), interrogative (questions), imperative (commands), and exclamatory (exclamations). Each sentence type follows specific syntactic rules.

Grammatical Roles: Syntax assigns grammatical roles to words and phrases within sentences. These roles include subject, verb, object, complement, and modifier. Understanding these roles is essential for constructing grammatically correct sentences.

Syntactic Rules: Languages have a set of syntactic rules that dictate how words and phrases can be combined to form grammatical sentences. These rules encompass aspects such as word agreement (e.g., subject-verb agreement), tense and aspect, and the use of auxiliary verbs.

Phrase Structure Grammar: One of the formal approaches to studying syntax is phrase structure grammar, which uses tree diagrams to represent the hierarchical structure of sentences. These trees show how words and phrases are organized within a sentence.

Transformational Grammar: Transformational grammar, developed by Noam Chomsky, explores the transformations and derivations that allow sentences to be changed or transformed into different forms while maintaining their underlying structure.

Ambiguity: Syntax also addresses issues of sentence ambiguity, where a single sentence can have multiple interpretations due to different syntactic structures or word orders. Resolving ambiguity is an important aspect of language comprehension.

Universal Grammar: The concept of universal grammar, proposed by Chomsky, suggests that there is a common underlying structure and set of principles shared by all human languages. Universal grammar is thought to be hardwired in the human brain and is responsible for the ability to acquire and produce language.

Syntax plays a fundamental role in language comprehension, production, and analysis. It provides the rules and structures that allow us to convey meaning through sentences and helps linguists understand the underlying principles that govern the structure of languages across the world.

Semantics

Semantics is the branch of linguistics that focuses on the study of meaning in language. It explores how words, phrases, sentences, and discourse convey meaning, and it seeks to understand the principles and processes that underlie our ability to communicate effectively through language. Here are some key aspects of semantics:

Meaning: At its core, semantics is concerned with meaning—the meaning of individual words, how words combine to form phrases and sentences, and how context influences interpretation. It addresses questions like “What does a word mean?” and “How do we understand the meaning of a sentence?”

Lexical Semantics: Lexical semantics deals with the meaning of individual words (lexemes) in a language. It explores word meanings, word senses, and the relationships between words, such as synonyms, antonyms, and homonyms.

Word Sense Disambiguation: Many words have multiple senses or meanings. Semantics helps resolve this ambiguity through word sense disambiguation, a process that determines which specific sense of a word is intended in a given context.

Compositional Semantics: Compositional semantics focuses on how the meanings of words and phrases combine to create the meaning of larger linguistic units, such as sentences and paragraphs. It examines the rules and principles governing this combination.

Truth Conditions: Semantics often involves defining the truth conditions of sentences. It explores when a sentence is considered true or false in different contexts and how the meaning of words contributes to this evaluation.

Pragmatics: While semantics deals with linguistic meaning, pragmatics extends beyond that to study how language is used in context to convey meaning. Pragmatics considers factors like speaker intentions, implicatures, and the effects of context on interpretation.

Ambiguity: Semantics addresses various forms of ambiguity, including lexical ambiguity (multiple meanings of words), structural ambiguity (multiple interpretations of sentence structures), and scope ambiguity (different interpretations based on the placement of words like “only” or “not”).

Sense and Reference: Semantics distinguishes between the sense (conceptual meaning) and reference (the actual entities or things in the world that a word or phrase points to) of linguistic expressions. This distinction is crucial for understanding how language relates to the external world.

Semantic Roles: Semantic roles, also known as thematic roles or theta roles, describe the relationship between verbs and the arguments (such as subjects, objects, and complements) in a sentence. Understanding these roles helps clarify the meaning of sentences.

Semantic Universals: Linguists explore whether there are universal principles and categories of meaning that apply across all languages, such as the distinction between nouns and verbs or the existence of tense and aspect categories.

Semantics plays a vital role in language understanding, interpretation, and communication. It helps us make sense of the world, express our thoughts and intentions, and comprehend the messages conveyed by others. Additionally, semantics is a key area of study in natural language processing and artificial intelligence, where the goal is to enable computers to understand and generate human language with precision and accuracy.

Dialects: Variations of a language that arise due to geographical, social, or cultural factors.

Geographical Dialects: Geographical factors play a significant role in the development of dialects. Different regions or areas within a country or linguistic community may have distinct ways of pronouncing words, using vocabulary, and structuring sentences. These regional variations are often referred to as regional dialects. For example, American English has regional dialects such as Southern English, New York English, and Midwestern English.

Social Dialects: Social factors, including socioeconomic status, education, and social identity, can also lead to the emergence of dialects. Within a single geographical area, people from different social backgrounds may speak the same language but with differences in vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammatical patterns. These variations are often referred to as social dialects or sociolects.

Cultural Dialects: Cultural factors, such as ethnicity, cultural heritage, and historical influences, can result in the development of cultural dialects. Speakers from specific cultural groups may use distinct linguistic features, idiomatic expressions, and vocabulary that are unique to their cultural identity. For example, African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is a cultural dialect spoken primarily by African Americans in the United States.

Phonological, Lexical, and Grammatical Differences: Dialectal variations can manifest in several ways, including differences in pronunciation (phonology), vocabulary (lexicon), and grammar (syntax). These variations can range from subtle differences in pronunciation to distinct words or grammatical structures that are unique to a particular dialect.

Dialect Continuum: In some cases, dialects exist on a continuum rather than as discrete categories. This means that neighboring regions or social groups may have dialects that gradually transition from one to another, with no clear boundary. Such dialect continua are common in many parts of the world.

Standard vs. Non-Standard Dialects: Dialects are often compared to a standardized form of the language, which serves as the norm for education, media, and official communication. Non-standard dialects, which deviate from the standard, are sometimes stigmatized or considered informal, but they are equally valid forms of language with their own linguistic rules.

Language Variation and Change: Dialects are not static; they can evolve over time due to various factors, including contact with other dialects or languages, migration, and societal changes. This dynamic nature of dialects contributes to the ongoing diversity of languages.

Preservation and Documentation: Linguists and researchers study dialects to document and analyze linguistic diversity. Efforts are made to preserve and promote the use of dialects, as they are an essential part of cultural heritage and linguistic diversity.

Dialects are a natural and integral part of language evolution and variation. They reflect the rich tapestry of human culture and history, and they continue to evolve and adapt to changing circumstances and influences.

Grammar: Rules governing the structure and formation of sentences and words in a language.

Grammar encompasses the rules and principles that govern the structure and formation of sentences and words in a language. It plays a crucial role in language comprehension, production, and communication. Let’s explore the concept of grammar further:

Grammatical Components: Grammar involves several components, including:

Syntax: The rules governing the structure of sentences, word order, and the arrangement of words in phrases and clauses.

Morphology: The rules governing the structure and formation of words, including prefixes, suffixes, and word roots.

Semantics: The study of meaning in language, including how words and phrases convey meaning and how context influences interpretation.

Phonology: The study of the sounds used in a language, including phonemes, intonation, and pronunciation rules.

Grammatical Rules: Grammar provides a framework for constructing sentences that are coherent and convey meaning. It includes rules for:

Word Agreement: Ensuring that words within a sentence agree in terms of number, gender, and tense. For example, subject-verb agreement.

Sentence Structure: Determining how words, phrases, and clauses are organized to create meaningful sentences.

Punctuation: Rules for using punctuation marks such as periods, commas, and quotation marks to indicate sentence boundaries and convey meaning.

Tense and Aspect: Indicating the time of an action or event and whether it is ongoing or completed through verb tense and aspect.

Grammatical Categories: Classifying words into categories such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and conjunctions based on their grammatical roles.

Prescriptive vs. Descriptive Grammar: Grammar can be viewed from both prescriptive and descriptive perspectives. Prescriptive grammar refers to the rules and norms advocated by language authorities and used as standards for “correct” language use. Descriptive grammar focuses on analyzing how language is actually used by speakers and writers, regardless of whether it adheres to prescribed rules. Linguists often adopt a descriptive approach to understand and document language as it is naturally spoken and written.

Variations in Grammar: Languages evolve over time, and different regions and communities may have their own variations of grammar. Dialects and sociolects may exhibit unique grammatical features while still adhering to the core principles of grammar.

Language Acquisition: Understanding grammar is essential for language learners as they acquire proficiency in a new language. It involves mastering the rules and structures that enable effective communication.

Language Evolution: Grammar can change and evolve over time due to language contact, cultural shifts, and societal changes. These changes may lead to shifts in grammatical rules and the introduction of new linguistic features.

Grammar is a fundamental aspect of language that governs how words and sentences are structured and used to convey meaning. It encompasses various components and rules, both prescriptive and descriptive, and is essential for effective communication and language acquisition.

Bilingualism and Multilingualism:

Bilingualism and multilingualism refer to the ability to speak and understand multiple languages. Bilingualism:

Definition: Bilingualism refers to the proficiency in and regular use of two languages by an individual or a community. A bilingual person is capable of speaking, understanding, reading, and writing in two languages.

Types: Bilingualism can take various forms, including balanced bilingualism (equal proficiency in two languages), dominant bilingualism (one language is more proficient than the other), and receptive bilingualism (understanding and speaking one language but mainly understanding the other).

Multilingualism:

Definition: Multilingualism is the ability to speak and understand three or more languages. Multilingual individuals or communities are proficient in and use multiple languages in their daily lives.

Types: Multilingualism can involve knowing several languages to varying degrees of proficiency. Some multilingual individuals may be fluent in multiple languages, while others may have basic conversational skills in several languages.

Benefits of Bilingualism and Multilingualism:

Cognitive Benefits: Bilingualism and multilingualism have been associated with cognitive advantages, including enhanced problem-solving skills, better multitasking abilities, and improved memory and concentration.

Cultural Benefits: Multilingual individuals often have a deeper understanding of different cultures and perspectives, which can foster intercultural communication and empathy.

Economic Benefits: Being bilingual or multilingual can enhance job opportunities and career prospects, particularly in fields that require language proficiency or international communication.

Linguistic Benefits: Multilingual individuals may have a heightened awareness of language structures, making it easier for them to learn additional languages.

Challenges and Considerations:

Code-Switching: Bilingual and multilingual individuals may switch between languages in conversation, a phenomenon known as code-switching.

Language Maintenance: The maintenance of multiple languages may require ongoing practice and exposure to all languages spoken to prevent language attrition or loss of proficiency.

Language Mixing: In multilingual environments, speakers may mix elements from multiple languages in their speech, creating a unique linguistic blend.

Language Acquisition:

Bilingualism can occur through various paths, including simultaneous acquisition (learning two languages from infancy), sequential acquisition (learning a second language after the first), and heritage language acquisition (learning a language spoken by one’s cultural or familial heritage).

Bilingualism and multilingualism are common in many parts of the world, and they contribute to linguistic diversity and cultural richness. These abilities offer numerous advantages, both cognitive and practical, and are valuable skills in an increasingly interconnected global society.

Theories of Language:

Noam Chomsky is a prominent linguist who has made significant contributions to the field of linguistics, and he is best known for his theory of Universal Grammar.

Noam Chomsky’s Theory of Universal Grammar:

Innate Language Capacity: Chomsky’s theory posits that humans are born with an innate capacity for language acquisition. He argues that this capacity is part of our genetic endowment and is unique to humans.

Universal Grammar (UG): Chomsky proposed the concept of Universal Grammar, which is a theoretical framework that suggests there is a common underlying structure and set of principles shared by all human languages. UG is the innate linguistic knowledge that enables humans to acquire and produce language.

Language Acquisition Device (LAD): Chomsky proposed the existence of a “language acquisition device” in the human brain. This hypothetical cognitive mechanism is responsible for facilitating the acquisition of language. According to Chomsky, the LAD allows children to rapidly learn the grammar and rules of their native language(s) through exposure to linguistic input.

Principles and Parameters: Within the framework of Universal Grammar, Chomsky introduced the idea of “principles” and “parameters.” Principles are universal linguistic rules or constraints that apply to all languages. Parameters, on the other hand, are settings that can vary from one language to another. Children, when exposed to a specific language, set the parameters of their innate Universal Grammar to match the linguistic characteristics of that language. This is how they acquire the grammar and structure of their native language.

Critical Period Hypothesis: Chomsky’s theory suggests that there is a critical period during early childhood when language acquisition is most efficient and effective. He proposed that if children do not acquire language exposure during this critical period, their ability to acquire language diminishes significantly.

Transformational Grammar: Chomsky also developed transformational grammar, a formal grammar framework used to analyze the syntax and structure of sentences in natural languages. Transformational grammar introduced the idea of transformation rules that derive different sentence structures from a common underlying structure.

Chomsky’s theory has had a profound influence on the field of linguistics and has sparked extensive research and debate. While some aspects of his theory have been widely accepted, others have been the subject of criticism and refinement. Universal Grammar and the innateness hypothesis continue to be important topics of discussion and investigation in linguistics and cognitive science.

Transformational Grammar is a linguistic theory and framework developed by Noam Chomsky in the 1950s and 1960s. It revolutionised the study of syntax (the structure of sentences) and provided a new way to understand how language is generated and interpreted. Transformational grammar focuses on the rules and structures that underlie a language, aiming to uncover the deep structure of sentences and how they are transformed into surface structures.

Key Features of Transformational Grammar:

Generative Grammar: Transformational grammar is a type of generative grammar, meaning it’s concerned with generating (producing) sentences in a language. It seeks to explain how native speakers of a language can produce an infinite number of sentences using a finite set of rules.

Deep Structure and Surface Structure: Transformational grammar introduces the concept of deep structure and surface structure. Deep structure represents the core meaning of a sentence, while surface structure is the actual sentence we produce or hear. Transformations are rules that convert deep structures into surface structures.

Universal Grammar: Chomsky proposed the existence of a universal grammar, a set of grammatical principles and rules that are common to all languages. According to this theory, all human languages share a deep underlying structure, and the differences among languages are variations on this universal grammar.

Chomskyan Hierarchy: Transformational grammar is part of the broader Chomskyan hierarchy of grammars, which categorizes formal grammars into different types based on their generative power. Transformational grammar belongs to the highest level of this hierarchy, known as context-free grammars.

Rules and Transformations: The theory postulates a set of rules and transformations that operate on the deep structure to derive the surface structure. These rules account for how sentences can be grammatically structured and how they can be altered to form new sentences.

Syntactic Structures: Transformational grammar places a strong emphasis on the analysis of syntactic structures, exploring the relationships between words and phrases within sentences.

Psycholinguistics: The theory has implications for psycholinguistics, the study of how humans process language in the mind. It provides insights into how people understand and produce sentences.

Applications: Transformational grammar has been influential in various fields, including linguistics, psycholinguistics, and natural language processing. It has been used to analyze and model the structure of natural languages, as well as to develop computer programs for language processing.

Transformational grammar is a linguistic framework that seeks to understand the underlying structure of language and how it is transformed into the sentences we use in everyday communication. It has been a foundational theory in the study of syntax and has had a significant impact on our understanding of language and its cognitive processes.

B.F. Skinner’s Behaviorist Theory:

B.F. Skinner, a prominent psychologist and behaviorist, proposed a theory that emphasized the role of conditioning and reinforcement in language acquisition. Here are the key points of Skinner’s behaviorist theory of language development:

Behaviorist Theory of Language Development:

Operant Conditioning: Skinner’s theory is rooted in the principles of operant conditioning, which is a type of learning that involves the association of behaviors with consequences. In operant conditioning, behaviors that are followed by positive consequences (reinforcement) are more likely to be repeated, while behaviors followed by negative consequences (punishment) are less likely to be repeated.

Verbal Behavior: Skinner introduced the concept of “verbal behavior,” which refers to the use of language as a form of behavior. According to Skinner, like other behaviors, language is learned through a process of stimulus-response associations.

Imitation and Reinforcement: Skinner argued that language development begins with imitation. Children learn language by imitating the speech of those around them. When a child produces sounds or words that are similar to those of adults, they receive positive reinforcement (praise or attention), which encourages them to continue using those language forms.

Operant Conditioning in Language Development: Skinner proposed that the development of grammatical structures and the acquisition of vocabulary are both the result of operant conditioning. When children produce grammatically correct sentences or use new words appropriately, they are reinforced with positive feedback, leading to the acquisition of language skills.

Negative Reinforcement of Errors: Skinner also noted that parents and caregivers often provide correction and negative feedback when children make grammatical errors or use language inappropriately. This negative reinforcement, according to Skinner, helps children refine their language skills by reducing errors.

Critiques and Limitations: Skinner’s behaviorist theory of language development has been criticized for oversimplifying the complex nature of language acquisition. It places a strong emphasis on imitation and reinforcement but does not adequately account for the innate cognitive abilities that children bring to the language-learning process. Additionally, it does not explain how children acquire complex grammatical structures or how they generate novel utterances.

It’s important to note that while Skinner’s behaviorist theory contributed to our understanding of learning and conditioning processes, it is not the dominant theory in contemporary linguistics and psychology. Contemporary theories of language development, such as the nativist theory proposed by Noam Chomsky, emphasize the role of innate cognitive structures and universal grammar in language acquisition. These theories argue that children have a natural predisposition for language learning, which goes beyond simple conditioning and reinforcement.

Sociocultural Theory (Lev Vygotsky):

Lev Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of language development emphasizes the critical role of social interactions and cultural context in the acquisition of language and cognitive development. Vygotsky’s theory is widely recognized and influential in the fields of psychology and education.

Here are the key components of Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory:

Sociocultural Theory of Language Development:

Social Interaction as a Foundation: Vygotsky believed that social interaction is the cornerstone of cognitive development, including language acquisition. He argued that children learn and develop through their interactions with more knowledgeable individuals, such as parents, caregivers, and peers.

Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD): Vygotsky introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which represents the gap between a child’s current level of development and their potential development with the guidance and support of a more knowledgeable person. In the ZPD, learners are capable of understanding and performing tasks with the assistance of a more skilled individual.

Scaffolding: Scaffolding refers to the support and guidance provided by more knowledgeable individuals to help learners accomplish tasks within their ZPD. This support can take various forms, such as explanations, modeling, encouragement, and feedback. Over time, as the learner gains competence, the level of scaffolding can be adjusted or reduced.

Private Speech: Vygotsky observed that young children often engage in private speech, which involves talking to themselves aloud as they work on tasks. He viewed this self-talk as a crucial developmental step, as it helps children regulate their behavior, plan, and solve problems. Private speech gradually becomes internalized and evolves into inner speech, which is silent and mental.

Cultural Context: Vygotsky emphasized the role of cultural context in shaping language development. He argued that language is not solely a product of individual cognition but is deeply embedded in the cultural and social practices of a community. Therefore, the language and communication patterns of a child’s cultural environment significantly influence their language development.

Language and Thought: Vygotsky proposed that language and thought are interconnected. Language serves as a tool for thought and cognitive development. Through social interactions and language use, children are able to internalize and organize their thinking processes.

Cultural Tools: Vygotsky referred to cultural tools, which include language, writing systems, and symbolic representations, as means through which culture is transmitted from one generation to the next. These cultural tools are essential for cognitive development and problem-solving.

Educational Implications: Vygotsky’s theory has important implications for education. He advocated for a “sociocultural approach” to teaching, where educators create a supportive and collaborative learning environment that encourages social interaction, peer learning, and guided instruction to facilitate cognitive development and language acquisition.

Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory underscores the significance of social interactions, cultural context, and scaffolding in the development of language and cognitive abilities. It provides a valuable framework for understanding how language and thought are shaped by the social and cultural environment in which individuals grow and learn.

Pedagogy:

Language Acquisition

Pedagogy, in the context of language acquisition, refers to the methods, strategies, and approaches used by educators and instructors to facilitate the learning and development of language skills in learners of all ages.

Language acquisition pedagogy encompasses a wide range of teaching practices aimed at helping learners acquire, understand, and effectively use a new language.

Here are some key aspects of pedagogy in language acquisition:

Approaches to Language Teaching:

Communicative Approach: This approach emphasizes the use of language for communication and real-life situations. It focuses on developing learners’ speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills within authentic contexts.

Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT): TBLT involves learners in completing language-related tasks or projects. It encourages active participation and problem-solving, promoting language acquisition through meaningful activities.

Grammar-Translation Method: This traditional method emphasizes grammar rules and translation between the target language and the native language. It is often used for teaching classical languages.

Audio-Lingual Method: This method emphasizes oral skills through repetitive drills and patterned exercises. It is often associated with behaviorist principles of language learning.

Total Physical Response (TPR): TPR is based on the idea that language learning can be facilitated through physical actions and commands. Learners respond to spoken language with physical actions.

Language Learning Strategies: Educators teach learners various strategies for language acquisition, including:

Listening comprehension: Techniques for improving listening skills, such as active listening, note-taking, and using context clues.

Reading comprehension: Strategies for understanding written texts, including skimming, scanning, and inferring meaning from context.

Vocabulary acquisition: Methods for expanding and retaining vocabulary, such as flashcards, mnemonic devices, and word associations.

Speaking and conversation: Activities that encourage speaking and interaction, such as role-playing, debates, and group discussions.

Writing skills: Approaches to developing writing skills, including brainstorming, outlining, drafting, and revising.

Assessment and Feedback: Effective pedagogy includes ongoing assessment and feedback mechanisms to evaluate learners’ progress and provide guidance for improvement. Assessment methods can include quizzes, tests, oral presentations, written assignments, and peer evaluations.

Cultural Awareness: Language acquisition pedagogy often incorporates cultural awareness and sensitivity. Learners are encouraged to understand the cultural context of the language they are acquiring, which enhances their ability to communicate effectively in real-world situations.

Technology and Language Learning: Modern pedagogy often leverages technology, including language learning apps, online resources, and digital communication tools, to enhance language acquisition. These tools offer interactive and multimedia experiences for learners.

Inclusive Pedagogy: Inclusive language acquisition pedagogy seeks to accommodate diverse learners, including those with different learning styles, abilities, and backgrounds. It promotes equity and ensures that all learners have access to language learning opportunities.

Motivation and Engagement: Effective language acquisition pedagogy aims to motivate and engage learners through relevant and interesting content, interactive activities, and a supportive learning environment.

Individualized Learning: Recognizing that learners have different needs and preferences, some pedagogical approaches offer opportunities for individualized learning plans and self-directed language acquisition.

Pedagogy in language acquisition encompasses a broad range of teaching methods and strategies aimed at helping learners develop language skills. Effective language teaching incorporates a combination of approaches and techniques tailored to the needs and goals of learners, while also considering cultural, technological, and inclusive aspects of language education.

Language Teaching Approaches: These approaches can vary in their focus, techniques, and goals. Here are some of the key language teaching approaches:

Communicative Approach:

Focus: Emphasizes the use of language for communication in real-life situations.

Techniques: Learners engage in authentic, interactive activities and tasks that require them to use the language in context.

Goals: Develops learners’ ability to communicate fluently and effectively in the target language, focusing on speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills.

Example Activity: Role-playing, group discussions, problem-solving tasks, and simulations.

Grammar-Translation Method:

Focus: Concentrates on teaching grammar rules and translation between the target language and the native language.

Techniques: Heavily relies on reading and translation exercises, often involving literary texts.

Goals: Aims to develop reading and writing proficiency, with a strong emphasis on accuracy in grammar and vocabulary.

Example Activity: Translating sentences or texts from the target language to the native language and vice versa.

Direct Method:

Focus: Advocates for teaching the target language directly, without the use of the native language.

Techniques: Emphasizes oral communication and listening comprehension, avoiding translation.

Goals: Aims to develop learners’ speaking and listening skills, with the belief that language should be learned as a living tool.

Example Activity: Conversational exercises, question-and-answer sessions, and using visual aids to support understanding.

Audio-Lingual Method:

Focus: Emphasizes the development of oral skills through repetitive drills and patterned exercises.

Techniques: Involves memorization and repetition of dialogues, sounds, and sentence structures.

Goals: Aims for mastery of pronunciation and fluency in speaking and listening.

Example Activity: Repeating dialogues, responding to prompts, and practicing pronunciation.

Total Physical Response (TPR):

Focus: Utilizes physical actions and commands to facilitate language learning.

Techniques: Learners respond to spoken language with physical actions, such as following instructions or acting out commands.

Goals: Develops comprehension skills and vocabulary through kinesthetic learning.

Example Activity: The teacher gives commands in the target language, and learners physically act out the commands.

Immersion:

Focus: Involves immersive language experiences where learners are exposed to the target language in a real-life context.

Techniques: Learners are surrounded by the language through social and cultural immersion experiences.

Goals: Develops natural language acquisition skills and cultural understanding.

Example Activity: Language immersion programs, study abroad experiences, and living in a community where the target language is spoken.

Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT):

Focus: Involves learners in completing language-related tasks or projects, often in pairs or groups.

Techniques: Promotes active participation and problem-solving within authentic contexts.

Goals: Develops communication skills and language proficiency through meaningful activities.

Example Activity: Collaborative projects, problem-solving tasks, and real-life assignments.

Language educators often choose teaching approaches based on factors such as learner goals, proficiency levels, cultural context, and pedagogical preferences.

Assessment: Methods for evaluating language proficiency

Assessment in language learning is a critical component of the teaching and learning process. It involves various methods and tools used to evaluate learners’ language proficiency, monitor their progress, and provide feedback on their language skills. Here are some common assessment methods in language education:

Standardized Language Tests:

Purpose: Standardized tests are designed to measure language proficiency according to predetermined criteria. They provide a standardized and objective way to assess learners’ skills.

Examples: TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language), IELTS (International English Language Testing System), DELF/DALF (Diplôme d’Études en Langue Française/Diplôme Approfondi de Langue Française), and DELE (Diplomas of Spanish as a Foreign Language).

Placement Tests:

Purpose: Placement tests are used to determine a learner’s current level of language proficiency and place them in an appropriate course or level.

Examples: Placement tests often include multiple-choice questions, writing prompts, and speaking assessments.

Formative Assessment:

Purpose: Formative assessment is conducted during the learning process to provide ongoing feedback to both learners and instructors. It helps identify areas for improvement and adjust instruction accordingly.

Examples: In-class quizzes, peer assessments, teacher feedback on assignments, and self-assessment activities.

Summative Assessment:

Purpose: Summative assessment occurs at the end of a course or instructional period to evaluate overall language proficiency and learning outcomes.

Examples: Final exams, end-of-term projects, and standardized proficiency tests.

Oral Proficiency Interviews (OPI):

Purpose: OPIs assess a learner’s speaking and listening skills through a one-on-one conversation with an examiner or interviewer.

Examples: ACTFL (American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages) OPI, ILR (Interagency Language Roundtable) OPI

Writing Assessments:

Purpose: Writing assessments evaluate learners’ written language skills, including grammar, vocabulary, organization, and coherence.

Examples: Essay exams, written assignments, and writing portfolios.

Listening Comprehension Tests:

Purpose: Listening comprehension assessments measure a learner’s ability to understand spoken language, including dialogues, lectures, and recordings.

Examples: Listening comprehension quizzes, multiple-choice listening exercises.

Reading Comprehension Tests:

Purpose: Reading comprehension assessments evaluate a learner’s ability to understand and interpret written texts in the target language.

Examples: Reading comprehension exercises, standardized reading tests.

Performance-Based Assessments:

Purpose: Performance-based assessments require learners to apply their language skills in real-world tasks or scenarios.

Examples: Role-plays, oral presentations, debates, skits, and language tasks that simulate real-life situations.

Portfolio Assessment:

Purpose: Portfolios are collections of a learner’s work, including written assignments, essays, projects, and reflections, compiled over time to demonstrate language growth.

Examples: Language learning portfolios, digital portfolios, and e-portfolios.

Self-Assessment and Peer Assessment:

Purpose: Self-assessment and peer assessment involve learners evaluating their own language proficiency or assessing the language skills of their peers.

Examples: Learners completing self-assessment checklists or rubrics, peer reviews of speaking or writing assignments.

Assessment in language learning should align with learning objectives and provide meaningful insights into learners’ progress. It plays a crucial role in guiding instruction, helping learners set goals, and ensuring that language learning outcomes are achieved. A balanced combination of assessment methods, including both formative and summative approaches, is often used to comprehensively evaluate language proficiency.

English in Use:

“English in Use” refers to the practical application of the English language in real-life situations. This concept encompasses various aspects of language use, including speaking, writing, listening, and reading, in everyday and professional contexts.

Here are some key points to understand about “English in Use” and its practical application:

Communication: English in Use focuses on effective communication in English. It involves using the language to convey thoughts, ideas, information, and emotions to others in a clear and understandable manner.

Speaking: In real-life situations, using English in spoken form is essential for conversations, presentations, discussions, interviews, and social interactions. Effective spoken communication involves pronunciation, fluency, and appropriate use of vocabulary and grammar.

Writing: Written communication in English is crucial for various purposes, including emails, reports, essays, letters, creative writing, and academic assignments. Good writing skills involve clarity, coherence, grammar, and proper organization of ideas.

Listening: Understanding spoken English in real-life situations, such as lectures, meetings, interviews, and conversations, is a vital aspect of English in Use. Listening skills include comprehension, note-taking, and the ability to follow and respond to spoken instructions or information.

Reading: Reading English materials, including books, articles, newspapers, websites, and documents, is an essential part of language use. Reading skills involve comprehension, vocabulary acquisition, and the ability to extract information from written sources.

Contextual Application: English in Use requires adapting language skills to different contexts, such as formal and informal settings, academic and professional environments, and various social situations. Being aware of cultural norms and communication etiquette is also important.

Proficiency Levels: Individuals may use English in Use at different proficiency levels, ranging from basic to advanced. Proficiency levels can vary depending on learners’ language goals, needs, and experiences.

Language Varieties: English is a global language with various regional and cultural variations. English in Use encompasses the use of different varieties of English, including British English, American English, Australian English, and more, depending on the context and audience.

Language Development: Continuous practice and exposure to English in real-life situations are crucial for language development and improvement. Engaging in authentic language use helps learners become more proficient over time.

Practical Skills: English in Use involves practical language skills, such as negotiating, persuading, problem-solving, and expressing opinions. These skills are valuable in professional, academic, and social contexts.

Language Proficiency Assessment: Proficiency in English in Use is often assessed through various means, including standardized language tests, interviews, writing samples, and evaluations of spoken communication.

“English in Use” emphasizes the practical application of the English language in everyday life, professional contexts, and social interactions. It encompasses a wide range of language skills and abilities, with a focus on effective communication and adaptability to different situations and environments.

Language Skills:

Language skills are essential components of language proficiency, and they encompass four primary areas: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Proficiency in these language skills is crucial for effective communication and language use in English. Let’s explore each of these language skills in more detail:

Listening Skills:

Definition: Listening skills involve the ability to understand spoken language in English, whether in conversations, lectures, presentations, or other forms of oral communication.

Importance: Effective listening is key to comprehending spoken information, following instructions, participating in conversations, and engaging with spoken content in various contexts.

Development: Listening skills can be developed through activities such as listening to podcasts, watching English-language films or TV shows, participating in conversations, and practicing active listening techniques.

Speaking Skills:

Definition: Speaking skills encompass the ability to express oneself verbally in English. This includes the pronunciation, fluency, vocabulary, and grammar used when communicating orally.

Importance: Speaking skills are vital for effective communication in everyday interactions, presentations, discussions, job interviews, and social interactions.

Development: Speaking skills can be improved through regular conversation practice, pronunciation exercises, language exchange with native speakers, and public speaking opportunities.

Reading Skills:

Definition: Reading skills involve the ability to understand written text in English, ranging from simple texts like books and articles to more complex materials such as academic papers or technical documents.

Importance: Proficient reading skills enable individuals to access information, gain knowledge, conduct research, and enjoy literature in English.

Development: Reading skills can be enhanced through regular reading habits, expanding vocabulary, and practicing comprehension strategies like skimming and scanning.

Writing Skills:

Definition: Writing skills encompass the ability to convey thoughts, ideas, and information in written form in English. This includes the use of grammar, vocabulary, organization, and clarity in writing.

Importance: Writing skills are valuable for academic assignments, professional communication, creative expression, and various forms of written correspondence.

Development: Writing skills can be honed through regular writing practice, constructive feedback from peers or teachers, and studying different types of writing styles and genres.

Proficiency in these four language skills is often considered essential for overall language competence. Depending on individual language goals and needs, learners may prioritize one or more of these skills. Language courses and programs typically aim to develop all four language skills to help learners become well-rounded and effective communicators in English. Additionally, integrated language learning approaches, where listening, speaking, reading, and writing are interconnected, can provide a holistic language learning experience.

Language Varieties:

Language varieties refer to the different forms of a language spoken by various communities and regions. In the case of English, there are numerous varieties and dialects spoken around the world. Recognizing and using different forms of English, such as British English, American English, and global varieties, is important for effective communication and cultural awareness. Here are some key points about language varieties in English:

British English:

Varieties: British English encompasses a range of regional dialects and accents spoken in the United Kingdom (UK). Notable varieties include Received Pronunciation (RP), also known as the “Queen’s English,” as well as Scottish English, Welsh English, and various regional dialects such as Scouse, Geordie, and Cockney.

Features: British English is characterized by specific pronunciation patterns, vocabulary choices, and spelling conventions that can differ from other varieties of English.

Usage: British English is the standard in the UK and is used in formal, educational, and administrative contexts. It is also widely recognized internationally due to the historical influence of the British Empire.

American English:

Varieties: American English encompasses a wide range of regional accents and dialects spoken in the United States. Notable varieties include Standard American English, Southern English, New York English, and various Midwestern and West Coast dialects.

Features: American English is known for its distinct pronunciation, vocabulary, and spelling variations compared to British English. These include differences in rhotic pronunciation (r-sound pronunciation) and vocabulary choices.

Usage: American English is the predominant variety spoken in the United States and is used in formal, educational, and administrative settings. It is also influential in global media and business.

Global Varieties:

International English: English is a global lingua franca, and as a result, there are numerous varieties of English spoken around the world. International English refers to a simplified form of English used for global communication, often characterized by a neutral accent and simplified grammar and vocabulary.

World Englishes: World Englishes encompass the various forms of English spoken in different countries and regions, each influenced by the local linguistic and cultural context. Examples include Indian English, Nigerian English, and Singaporean English.

Pidgin and Creole Languages: Some regions have developed creole languages or pidgin languages based on English, incorporating elements from local languages. Examples include Jamaican Patois and Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea.

Recognizing and understanding these different varieties of English is important for effective communication and cultural sensitivity. Language learners and speakers may encounter various forms of English in different contexts, and being aware of regional differences can enhance communication and cross-cultural understanding. Additionally, individuals may choose to adapt their language use to the specific variety of English used in their professional or social interactions.

A table highlighting some key differences between British English, American English, and Indian English:

Aspect | British English | American English | Indian English |

Spelling | “colour,” “centre,” “theatre” | “color,” “center,” “theater” | “colour,” “centre,” “theatre” |

Vocabulary | “lorry” (truck), “biscuit” (cookie) | “truck,” “cookie” | “lorry” (truck), “biscuit” (cookie) |