🌍 Colonial Tongue, Native Spirit

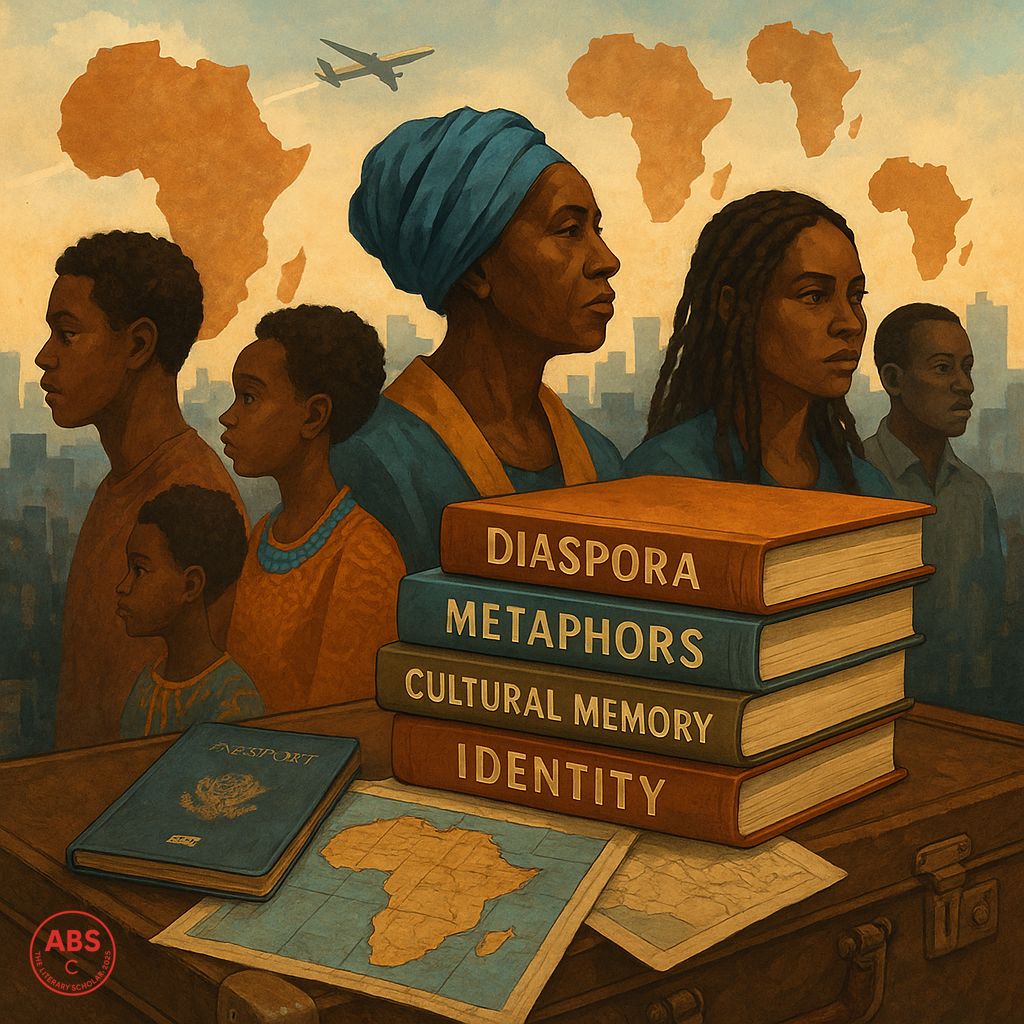

African literature in English is what happens when centuries of storytelling, fire circles, and ancestral wisdom meet the bureaucratic horror of colonial grammar. It’s a dance—part resistance, part reinvention—where English is no longer the invader, but the instrument. At first, the language arrived with guns and gospel. Now, it leaves with irony and deeply uncomfortable metaphors. The literature that grew out of this—AfriLit—is not content to merely describe a tree. It wants to tell you who planted it, who chopped it, who cursed it, and why its ghost still haunts the sentence.

Don’t expect it to whisper. AfriLit speaks in many tongues—some braided in trauma, some tuned to praise, all fiercely unapologetic. It’s literature that remembers too much, forgives too little, and explains absolutely nothing twice. It’s dusty roads and postcolonial migraines, cattle songs and courtroom transcripts. It doesn’t fit into neat chapters because its history wasn’t written neatly. It stutters, sings, scolds, and sometimes just stares at you until you admit you know nothing. And that’s the point.

✍️ ABS with a Dictionary and a Djembe

And now here comes ABS, The Literary Scholar—someone who usually carries around Shakespeare but has decided to set it down gently for a while to listen to something less imperial and far more rhythmic. ABS enters AfriLit not as a tourist with a highlighter, but as a quiet guest at a loud gathering. A gathering where every sentence may begin in English, but always ends in something older, wiser, and possibly translated from thunder.

The goal isn’t to decode Africa. Please. The continent’s already done enough explaining. ABS is here to absorb, interpret, maybe chuckle awkwardly at a proverb about goats, and absolutely marvel at how storytelling here is both survival strategy and sacred art. AfriLit is not a genre—it’s a genre bender. It is riddled with riddles, heavy with history, and sharp enough to make the reader bleed a little—intellectually, of course. The Scholar is all in, armed with curiosity, reverence, and just enough audacity to call it beautiful, complicated, and utterly essential.