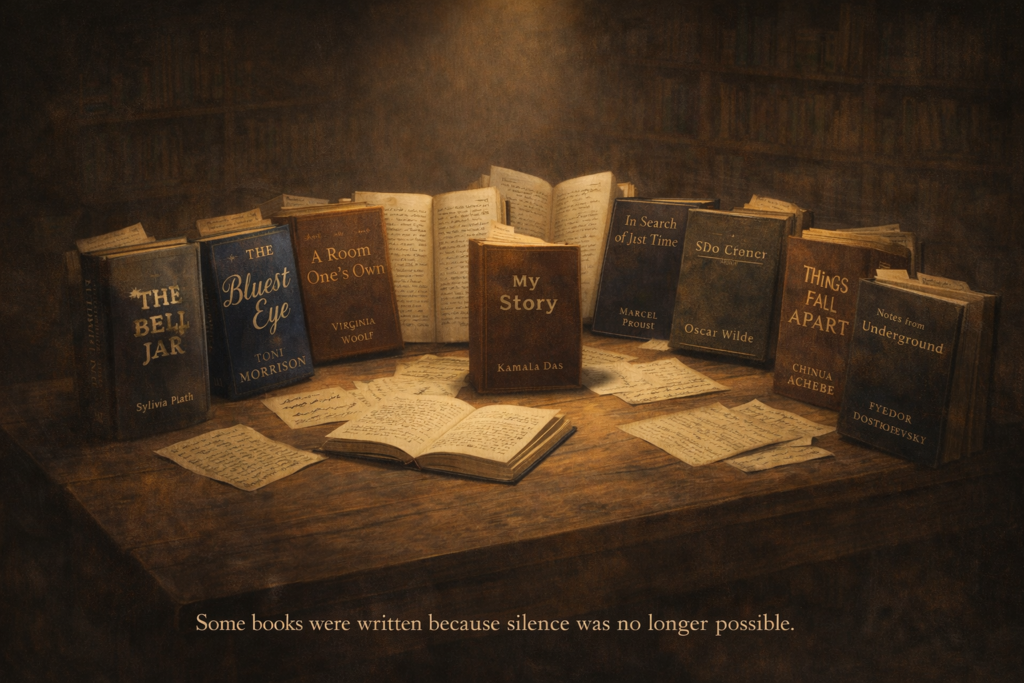

When Writing Changed the Author Before It Ever Reached the Reader

ABS BELIEVES

ABS believes that some books are not acts of communication but acts of survival.

They are written not to persuade the world, but to steady the writer.

The reader arrives later, almost accidentally.

Most books arrive with good manners. They introduce themselves politely, pretend they are here to enlighten readers, improve society, or at least make a syllabus feel meaningful. But some books walk in looking slightly unwell. They were not written to be admired. They were written because the author had run out of other options. These writers did not sit down thinking of influence, legacy, or reader response. They wrote because something inside them would not shut up, would not heal, would not make sense unless it was dragged into language and stared at. This scroll is about those books. Not the ones that changed history. The ones that changed the person holding the pen.

“I write only because there is a voice within me that will not be still.”

— Sylvia Plath

When Toni Morrison wrote The Bluest Eye, she was not trying to educate America. She was trying to read a book that did not exist yet. That absence bothered her more than reception ever could. Virginia Woolf was not drafting a feminist manifesto so much as building a psychological safety plan. Money and rooms were not metaphors; they were survival equipment. Dostoevsky did not invent the Underground Man for our philosophical amusement. He put his own bitterness, contradiction, and post-prison rage on the page so it would stop poisoning him privately. These writers chose their subjects the way one chooses a wound. Not dramatically. Necessarily.

“If there is a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

— Toni Morrison

Kamala Das did not write My Story to shock polite society, though society gasped on cue. She wrote because silence was no longer sustainable. Oscar Wilde did not write De Profundis to polish his tragic image; prison had already dismantled that luxury. What remained was self-knowledge, painfully earned. Even Proust, sealed in illness and memory, was not reconstructing society. He was reconstructing himself, one sentence at a time, because time had become personal before it ever became philosophical. These books were not born out of confidence. They were born out of pressure.

“Where there is sorrow, there is holy ground.”

— Oscar Wilde, De Profundis

This is why these works matter here. Not because they are great books, though they are. But because they reveal something far less comfortable: that writing is often an act of self-negotiation. An argument with one’s own fractures. The reader comes later. Sometimes much later. The urgency belonged to the writer first.

That’s where this scroll begins.

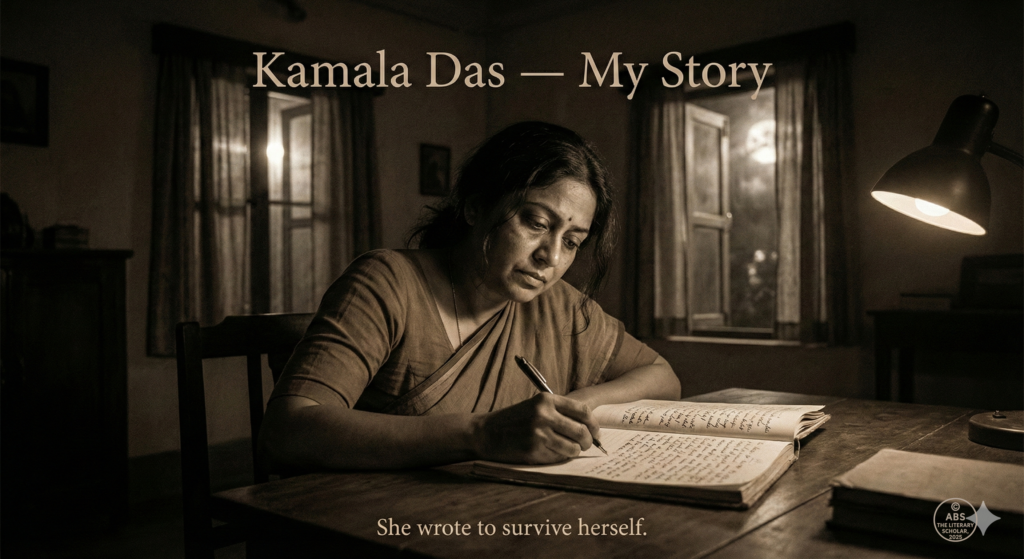

Kamala Das – My Story

She wrote to survive herself.Toni Morrison – The Bluest Eye

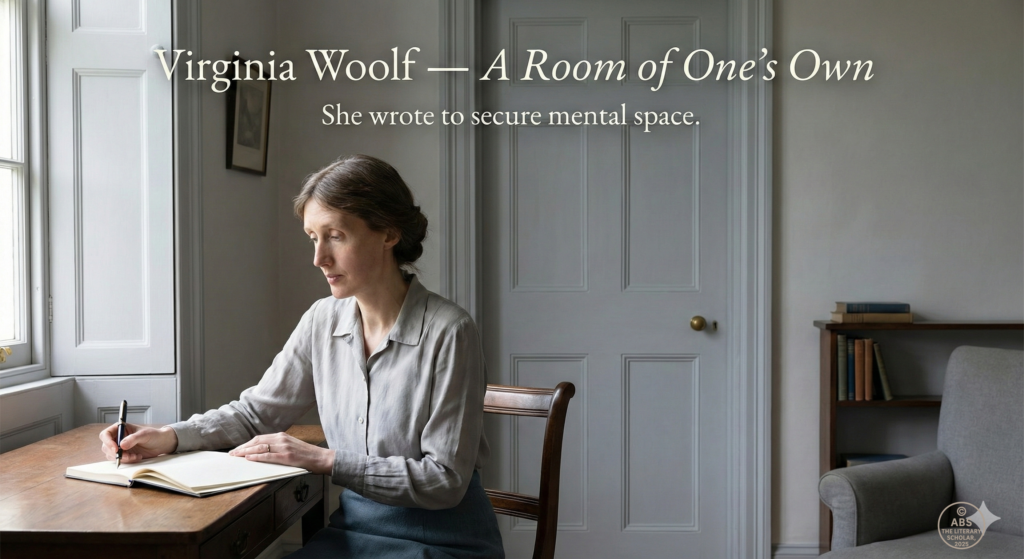

She wrote to correct a cultural silence.Virginia Woolf – A Room of One’s Own

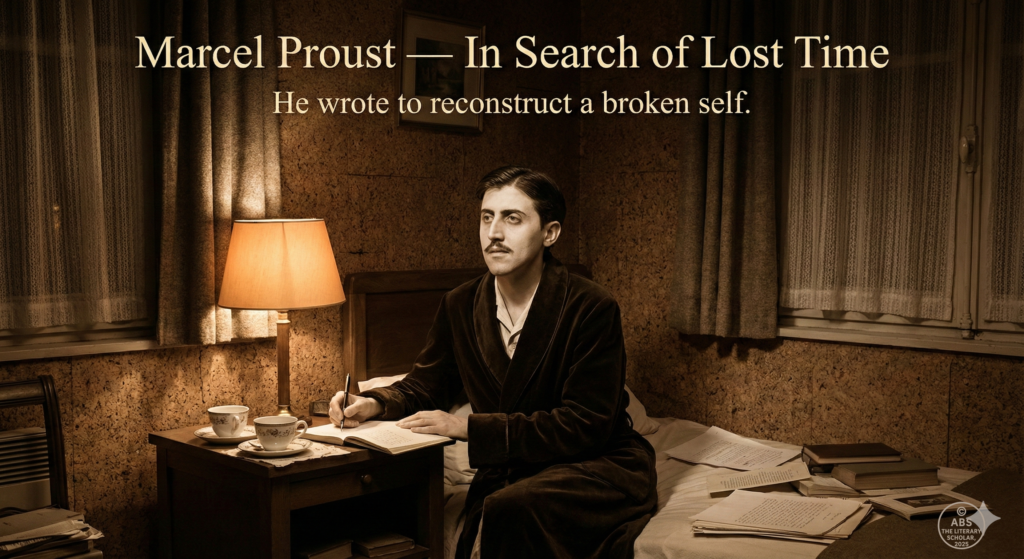

She wrote to secure mental space.Marcel Proust – In Search of Lost Time

He wrote to reconstruct a broken self.Jean-Jacques Rousseau – Confessions

He wrote to justify his own existence.Fyodor Dostoevsky – Notes from Underground

He wrote to confront his own contradictions.Oscar Wilde – De Profundis

He wrote to dismantle his own persona.Sylvia Plath – The Bell Jar

She wrote to name the fracture.James Baldwin – Notes of a Native Son

He wrote to refuse inherited bitterness.Simone de Beauvoir – Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter

She wrote to think herself into freedom.

1. Kamala Das – My Story

She wrote to survive herself.

Kamala Das did not write My Story because Indian literature needed an autobiography. Indian literature had autobiographies. What it did not have, and what it was deeply uncomfortable receiving, was a woman who refused to be respectable on paper. Das did not arrive with a mission to reform society or liberate womanhood as an abstract cause. She wrote because the cost of not writing had become higher than the cost of being exposed.

Born as Kamala Surayya in Kerala, raised between a traditional matrilineal household and an English-speaking colonial education, Das lived in a constant state of divided inheritance. She belonged everywhere and nowhere at once. Marriage arrived early. Desire arrived uninvited. Silence arrived as expectation. Writing, then, was not a career choice. It was a pressure valve.

My Story, first published in 1976, presents itself as an autobiography, but calling it that is misleading. This is not a chronological account of a life. It is an emotional excavation. Das moves erratically between childhood, marriage, sexual encounters, betrayal, illness, motherhood, and despair, not because she lacks discipline, but because memory itself does not queue politely. The book mirrors the mind of someone trying to assemble herself while speaking.

“I was childless, I was loveless, I was frightened.”

This is not confession for confession’s sake. This is naming. And naming, for Das, was the first act of survival.

Why did she choose autobiography? Because fiction would have allowed distance. Distance was the one luxury she could not afford. Writing directly about the body, about female desire, about marital suffocation, about loneliness, was the only way to reclaim ownership over experiences that had been domesticated into silence. Das was not interested in being symbolic. She was interested in being real.

The scandal that followed publication says more about the reader than the writer. Critics accused her of exhibitionism, immorality, attention-seeking. What disturbed them was not sex. It was agency. A woman speaking of her own body without apology was intolerable, especially in English, the language already associated with authority. Das broke two rules at once. She spoke. And she spoke in the master’s tongue.

“I speak three languages, write in two, dream in one.”

That line alone explains the book. My Story is written from the fracture of language itself. English becomes both shield and weapon. It allows distance from the domestic cage while also exposing her to public judgment. Yet she chooses it deliberately, because Malayalam would have demanded a different obedience. English lets her disobey more cleanly.

What did Das gain from this book? Not peace. Not approval. Not stability. She gained something harder and more essential: voice without permission.

Before My Story, Kamala Das was already a poet, already controversial, already visible. After My Story, she became undeniable. More importantly, she became legible to herself. Writing the book did not solve her contradictions. It allowed her to carry them without suffocation.

This is where the distinction between writer-gain and reader-gain becomes crucial. Readers gained shock, voyeurism, and later, academic interest. Writers and students quote My Story now as a feminist landmark. That recognition arrived decades later. Das did not write for that future. She wrote for the moment when silence was killing her faster than judgment.

“It is I who laugh, it is I who make love and then feel shame.”

The gain for the reader is intellectual. The gain for the writer was existential.

Das once admitted that parts of the autobiography were exaggerated, blurred, even fictionalised. Critics leapt at this as proof of dishonesty. They missed the point entirely. Emotional truth was her only contract. Precision was irrelevant. Survival was not.

My Story did not make Kamala Das happier. It made her less trapped. That matters more.

If this book were judged by the usual metric of influence, it would sit comfortably as a feminist text, a confessional narrative, a postcolonial female autobiography. But that is the reader’s classification. For the writer, the book functioned differently. It was not an argument. It was a release.

This is why My Story belongs in this scroll. Not because it changed Indian literature, though it rattled it. But because it changed the conditions under which Kamala Das could continue to exist as herself.

She did not write to be understood.

She wrote so she could breathe.

That is writing that saves the writer first.

Toni Morrison – The Bluest Eye

She wrote to correct a cultural silence.

Toni Morrison did not begin The Bluest Eye with a plan to educate America. She began with a disturbance. A private one. As she later admitted in interviews, she wanted to read a book about a Black girl who desired blue eyes and what that desire did to her interior life. She searched for it. It did not exist. That absence bothered her enough to write the book herself. Not to fill a gap in literature, but to confront a silence she could no longer ignore.

Published in 1970, The Bluest Eye emerged at a time when Black characters were still often filtered through white sympathy, sociological explanation, or moral uplift. Morrison rejected all three. She was not interested in making her characters palatable. She was interested in making them visible. Especially the ones literature preferred not to see.

“Quiet as it’s kept, there were no marigolds in the fall of 1941.”

The novel opens with this line not as atmosphere, but as warning. Something essential has failed to grow. What follows is the story of Pecola Breedlove, a young Black girl who comes to believe that possessing blue eyes will make her beautiful, lovable, and safe. This belief is not presented as childish fantasy. It is shown as a logical conclusion in a world where every image of goodness, success, and desirability excludes her.

Morrison chose this subject because she understood something unsettling: racism does not only operate from the outside. It settles inside. It teaches its victims to measure themselves using someone else’s mirror. Pecola’s desire for blue eyes is not vanity. It is desperation. And Morrison refuses to soften it.

“If those eyes of hers were different, that is to say, beautiful, she herself would be different.”

This is the core wound of the novel. Identity collapses into appearance. Worth collapses into visibility. Pecola does not want to be seen; she wants to disappear into what she believes the world rewards. Morrison does not rescue her from this belief. She traces it carefully, relentlessly, through family, community, history, and language itself.

Why did Morrison write this book? Because she wanted to examine the damage done when beauty becomes moral authority. When whiteness is mistaken for innocence. When Blackness is taught to apologize for existing. She wrote the book she needed to read because the cultural conversation had skipped over this damage, preferring heroic narratives and redemptive arcs.

The novel famously denies the reader comfort. Pecola is not saved. There is no restorative ending. This was not oversight. It was intention. Morrison believed that consoling the reader would be dishonest. The real transformation she was after was not emotional relief, but moral clarity.

“Love is never any better than the lover.”

This line cuts through the novel like a verdict. Morrison is not blaming individuals alone. She is exposing a system of values that teaches people how to love poorly. Pecola’s parents, her community, even well-meaning observers are implicated. No one is innocent. That refusal to assign simple villains is part of Morrison’s quiet brutality.

Now, the crucial question for this scroll: what did Morrison gain from writing The Bluest Eye?

She did not gain immediate acclaim. The novel sold modestly at first. It was later challenged, banned, and misunderstood. But Morrison gained something more foundational. She gained a literary position she would occupy for the rest of her career: writing from inside Black experience without translation or apology.

This book clarified Morrison’s relationship to language, audience, and responsibility. She decided, here, that she would never write to explain Black life to white readers. She would write to tell the truth as she saw it. The silence she corrected was not only cultural. It was internal. She freed herself from the burden of accommodation.

For readers, The Bluest Eye is devastating. For Morrison, it was anchoring. It told her what kind of writer she was going to be.

Later novels would grow in scope, complexity, and recognition. But the moral spine was set here. This was the book that taught Morrison she did not need permission to tell uncomfortable truths. That writing could begin with absence and still insist on authority.

The Bluest Eye did not begin as a gift to readers. It began as a necessity for the writer. The reader arrived later, shaken.

That is why this book belongs in this scroll.

It did not change the world first.

It changed the writer’s direction.

And sometimes, that is the more dangerous transformation of all.

Virginia Woolf – A Room of One’s Own

She wrote to secure mental space.

Virginia Woolf did not write A Room of One’s Own because the world needed another essay on women and literature. The world already had opinions. What it did not have was honesty about the conditions under which thinking itself becomes possible. Woolf was not arguing for rights in the loud, declarative sense. She was arguing for sanity. Quietly. Precisely. With a scalpel, not a banner.

The book grew out of two lectures delivered in 1928 to women students at Cambridge. That origin is important. Woolf was not speaking from a position of abstraction. She was responding to a room full of intelligent women who had been invited into education but not fully equipped to survive it. The lecture became an essay. The essay became a book. The book became a map.

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

This line is often quoted, rarely understood. It is treated like a slogan. Woolf did not mean it as one. She meant it literally. Money is time. A room is uninterrupted thought. Without these, creativity collapses into exhaustion. Woolf was naming a structural problem that masqueraded as a personal failure. Women were not less talented. They were systematically interrupted.

Why did Woolf choose this subject? Because she was living the consequences of its absence. Long before A Room of One’s Own, Woolf had experienced breakdowns, institutionalisation, and periods where the act of thinking itself became dangerous. She understood, intimately, that creativity without protection is not noble. It is destructive.

This book is often read as feminist theory. It is also a survival manual.

“Intellectual freedom depends upon material things.”

That sentence carries no romance. No uplift. Just fact. Woolf strips away the mythology of genius and replaces it with economics, architecture, and silence. She refuses to glorify suffering. She refuses to pretend that art blooms naturally under oppression. That refusal is the book’s quiet radicalism.

Woolf invents Judith Shakespeare, the fictional sister of William, not to provoke sympathy but to prove inevitability. Talent without conditions does not flower. It burns out. Judith’s tragedy is not lack of genius. It is lack of space. Woolf is not asking the reader to mourn Judith. She is asking the reader to stop producing Judiths.

“For masterpieces are not single and solitary births; they are the outcome of many years of thinking in common.”

Here is where the book reveals what Woolf herself gained from writing it. A Room of One’s Own clarified Woolf’s own relationship to tradition. She stopped seeing herself as an anomaly and started seeing herself as part of an interrupted lineage. Writing the book allowed her to reposition herself not as a fragile exception, but as a continuation that had been artificially delayed.

The gain was psychological. Woolf secured legitimacy for her own thinking. She no longer had to internalise exclusion as inadequacy.

It is important to note what Woolf does not do in this book. She does not rage. She does not accuse individuals. She does not perform outrage. Her tone is controlled to the point of appearing detached. This was not politeness. It was strategy. Woolf understood that anger, especially from women, would be dismissed as emotional excess. So she chose clarity instead.

“I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.”

This line is deceptively light. It carries centuries of erasure. Woolf allows the reader to arrive at the conclusion themselves. She trusts intelligence. That trust is part of what writing the book gave her back.

Now, what did the reader gain? Insight. Framework. Language. What did Woolf gain? Stability.

By articulating the material and mental conditions of creativity, Woolf built a case for her own way of living and working. She justified the need for solitude, financial independence, and intellectual autonomy. This was not indulgence. It was maintenance.

After A Room of One’s Own, Woolf wrote with greater structural confidence. The book did not remove her vulnerability, but it gave her a rationale for protecting herself. Writing ceased to be something she defended apologetically. It became something she organized her life around.

That distinction matters.

A Room of One’s Own did not set out to inspire readers. It set out to clear space. For women. For Woolf. For thinking itself.

The reader benefits. The writer survives.

And sometimes, survival is the most radical outcome literature can offer.

Marcel Proust – In Search of Lost Time

He wrote to reconstruct a broken self.

Marcel Proust did not write In Search of Lost Time to narrate a life. He wrote it to recover one. By the time he began the novel in earnest, Proust was ill, isolated, nocturnal, and largely removed from public life. Asthma had narrowed his world to rooms, beds, and memory. Society had already moved on without him. Writing became the only place where time could be negotiated rather than endured.

This matters, because In Search of Lost Time is often misunderstood as a leisurely, indulgent meditation on memory. It is not leisurely at all. It is urgent. The length of the novel is not excess; it is compensation. Proust was racing against physical decline, using sentences as scaffolding to hold together a self that threatened to dissolve.

“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.”

That sentence is not philosophy for readers. It is a working principle for the writer. Proust had lost access to the external world. What he still had was perception. Memory became his terrain, not out of nostalgia, but out of necessity.

Why did he choose memory as his subject? Because memory was the only thing not yet taken from him. His social life had collapsed. His health was unreliable. His days and nights were inverted. What remained was the mind’s ability to move freely through time. Writing allowed him to inhabit moments he could no longer physically reach.

The famous madeleine scene is often romanticised. In reality, it establishes the novel’s governing mechanism: involuntary memory as a force stronger than will. Proust is not interested in remembering on command. He is interested in what memory does when it arrives uninvited, carrying sensation, emotion, and identity with it.

“Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were.”

This is not a disclaimer. It is a declaration. Proust understands that memory is creative, selective, and unreliable. That unreliability does not weaken it. It makes it usable. The self, in Proust’s view, is not a stable object. It is an accumulation of impressions that must be constantly reorganized.

This is where the novel becomes personal in a way readers often miss. In Search of Lost Time is not about society, salons, or aristocracy, though it contains them in abundance. It is about making sense of one’s own inner continuity when external continuity has failed.

Proust’s narrator observes love, jealousy, desire, disappointment, and habit with microscopic attention because these were not abstractions for him. They were lived experiences revisited under isolation. Writing the novel allowed Proust to examine patterns in his own emotional life without being destroyed by them.

“Happiness is beneficial for the body, but it is grief that develops the powers of the mind.”

This line is often quoted with approval. It should not be. Proust is not celebrating suffering. He is acknowledging its role in sharpening awareness. Grief forced him inward. Writing gave that inwardness structure.

Now, what did the reader gain? An unprecedented exploration of consciousness. A new relationship to time. A redefinition of narrative itself. But those gains are secondary to what the book did for Proust.

Writing In Search of Lost Time allowed him to reconcile himself with the life he did not live. The social success he missed. The relationships that failed. The health he never had. Through writing, he could place these losses into a coherent pattern rather than experiencing them as meaningless absence.

The novel also resolved Proust’s anxiety about art. Early in life, he feared he lacked originality. By the end of the book, he arrives at a radical conclusion: originality is not invention, but perception. The artist’s task is not to create new material, but to see existing material truthfully.

“The only true paradise is the paradise we have lost.”

This is not nostalgia. It is recognition. Writing allowed Proust to recover lost time not by reliving it, but by understanding it. That understanding stabilized him. It gave his suffering form.

It is no accident that the novel ends with the narrator resolving to write the very book we have just read. The circularity is deliberate. Writing becomes the act that retroactively gives life meaning. Without the book, the life fragments. With it, the fragments align.

In Search of Lost Time did not heal Proust’s body. It healed his relationship with time, memory, and selfhood. That is not a gift offered primarily to readers. It is a reconstruction undertaken by the writer.

This is why Proust belongs in this scroll.

He did not write to escape life.

He wrote to reassemble it.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau – Confessions

He wrote to justify his own existence.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau did not write Confessions to confess in the modern, apologetic sense. He wrote to argue his case against the world. By the time he began the book, Rousseau believed himself misunderstood, misrepresented, betrayed, and persecuted by friends, philosophers, and society at large. Writing was not reflection. It was self-defence.

That distinction matters, because Confessions is often treated as the birth of modern autobiography. In form, yes. In intention, no. This is not a calm looking-back. It is a confrontation staged in advance.

“I have resolved on an enterprise which has no precedent, and which, once complete, will have no imitator.”

The arrogance is unmistakable. So is the urgency. Rousseau does not ease into the narrative. He announces himself as a singular case. Not exemplary. Not instructive. Singular. That alone tells us why he wrote the book. He felt erased by interpretation. Writing became his attempt to reclaim authorship over his own image.

Rousseau lived in a century that prized reason, sociability, and intellectual consensus. He possessed none of these comfortably. Suspicious, emotionally volatile, and increasingly paranoid, Rousseau experienced society not as community but as threat. Relationships failed. Patronage collapsed. Exile followed. What remained was the self, locked in argument with the world.

Confessions, written between 1765 and 1770, reconstructs Rousseau’s life from childhood onward, exposing shameful incidents, sexual humiliations, moral failures, and social embarrassments with startling openness. He admits to theft, cowardice, abandonment, and cruelty. But this honesty is not humility. It is strategy. By revealing everything, he leaves no room for others to accuse him.

“I may omit or add facts, but I cannot alter feelings.”

This sentence is Rousseau’s contract with the reader. Emotional truth matters more than factual precision. He is not interested in accuracy as historians define it. He is interested in authenticity as self-recognition. That distinction places Confessions firmly in this scroll.

Why autobiography? Because Rousseau believed no one else could tell his story without distortion. He distrusted biography, commentary, and interpretation. Only self-narration could restore justice. Writing became a courtroom where Rousseau was both defendant and witness.

The tone of the book unsettles modern readers. Rousseau is often self-pitying, defensive, and grandiose. He anticipates criticism and argues with it in advance. This is not accidental. Confessions is written under the pressure of imagined judgment. The reader is cast as tribunal.

“Let the trumpet of the Last Judgment sound when it will, I shall come forward with this book in my hand.”

This is not metaphor. This is obsession. Rousseau feared moral misrecognition more than death. Writing the book allowed him to stabilize a self that felt perpetually under threat. Whether the reader believes him is secondary. What mattered was that he believed he had finally spoken.

Now, what did Rousseau gain from writing Confessions?

He did not regain social acceptance. He did not repair broken friendships. He did not calm his paranoia. But he gained narrative control. The ability to say, “This is who I am,” without mediation. In a world where he felt misread, writing allowed him to anchor his identity in his own words.

This is where reader-gain and writer-gain diverge sharply. Readers gained a new genre: introspective autobiography. A model of radical self-exposure that would influence Romanticism and beyond. Rousseau gained something less grand but more vital: self-legibility.

The act of writing organized his contradictions. It allowed him to see his flaws not as random failures but as part of a coherent temperament. That coherence mattered to him more than virtue. Rousseau was not trying to appear good. He was trying to appear whole.

Critics often accuse Rousseau of narcissism. They are not wrong. But narcissism here is symptom, not cause. Confessions is the record of a man who could not survive being misinterpreted. Writing became a form of psychological containment.

“I am not made like anyone I have ever known.”

This line could be read as arrogance or desperation. In context, it is both. Writing allowed Rousseau to make peace with his difference by naming it relentlessly.

Confessions did not resolve Rousseau’s conflicts with the world. It resolved his conflict with himself. He stopped waiting to be understood. He wrote himself into permanence instead.

That is why this book belongs here.

Not because it redeems Rousseau.

But because it explains him to himself.

He wrote to justify his existence.

The reader inherited the genre by accident.

Fyodor Dostoevsky – Notes from Underground

He wrote to confront his own contradictions.

Fyodor Dostoevsky did not write Notes from Underground to explain philosophy. He wrote it to quarrel with himself. By the time this short, ferocious text appeared in 1864, Dostoevsky had survived mock execution, Siberian imprisonment, poverty, gambling addiction, epilepsy, and ideological disillusionment. Whatever faith he had once placed in rational systems, progress, or tidy moral explanations had been violently stripped away. What remained was a mind at war with its own impulses.

Notes from Underground is not a novel in the conventional sense. It has no plot worth summarising, no hero worth admiring, and no moral worth extracting neatly. That is precisely the point. Dostoevsky invents the Underground Man not as a character to be followed, but as a voice to be endured. A voice that resists logic, sabotages happiness, and takes pride in its own humiliation.

“I am a sick man… I am a spiteful man.”

There is no easing into this book. The narrator announces himself as pathological. But Dostoevsky is not diagnosing someone else. He is externalising parts of himself that polite society and fashionable philosophy had tried to suppress. This is confession without absolution.

Why did Dostoevsky choose this subject? Because he was deeply suspicious of the emerging belief that human beings are rational creatures who seek happiness when properly organized. The utopian thinkers of his time believed that suffering could be engineered out of existence. Dostoevsky knew better. Prison had taught him that suffering is not an error in the system. It is part of the system.

“Man needs only independent choice, whatever that independence may cost.”

This line cuts to the bone of the book. The Underground Man insists on choosing against his own interest simply to prove that he is free. This is not philosophy. It is lived experience. Dostoevsky understood the irrational pull of self-sabotage because he had lived it repeatedly. Gambling, destructive relationships, ideological swings—his life resisted coherence.

Writing Notes from Underground allowed Dostoevsky to face that resistance honestly. Not to cure it. To name it.

The book is structured in two parts: the first a furious monologue against rationalism, the second a series of humiliating social encounters. Together, they form a psychological anatomy of resentment. The Underground Man despises others, then despises himself for despising them. He longs for connection, then ensures its failure. This oscillation is not exaggerated. It is precise.

“I say let the world go to hell, but I should always have my tea.”

The humor is cruel and revealing. The Underground Man wants dignity but clings to petty comforts. This contradiction is not mocked from a distance. It is inhabited. Dostoevsky is not superior to his creation. He is implicated.

Now the crucial question for this scroll: what did Dostoevsky gain from writing this book?

He gained clarity about the enemy he was truly fighting. Not Western rationalism alone. Not socialism. Not science. But the fantasy that human beings can be simplified. Writing Notes from Underground freed him from the obligation to pretend otherwise.

After this book, Dostoevsky’s novels deepen in moral and psychological complexity. Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, The Brothers Karamazov—all carry the Underground Man’s DNA. The difference is scale. The confrontation begins here.

For readers, Notes from Underground is uncomfortable. It refuses inspiration. It exposes impulses readers prefer to deny. That discomfort is the reader’s gain. For Dostoevsky, the gain was something else: permission to write without reconciliation.

He no longer needed to resolve contradictions. He could explore them. He could allow characters to be wrong, self-destructive, and aware of it. Writing stopped being a search for moral symmetry. It became an investigation of moral chaos.

“Suffering is the sole origin of consciousness.”

Again, this is not an endorsement. It is an observation. Writing the book allowed Dostoevsky to convert suffering into articulation rather than paralysis. The Underground Man may be trapped, but the author is not. The act of writing creates distance where life offered none.

Notes from Underground did not make Dostoevsky more optimistic. It made him more honest. That honesty shaped everything he wrote afterward.

This book belongs in this scroll because it did not enlighten Dostoevsky’s readers first. It clarified Dostoevsky’s position as a writer: against simplification, against moral shortcuts, against any system that denies the complexity of the human will.

He wrote to confront his own contradictions.

The reader inherits the confrontation.

Oscar Wilde – De Profundis

He wrote to dismantle his own persona.

Oscar Wilde did not write De Profundis as literature. He wrote it as reckoning. By the time he began the long letter in Reading Gaol in 1897, the public Wilde was finished. The wit, the epigrams, the velvet jackets, the cultivated performance of brilliance had collapsed under trial, conviction, and imprisonment. What remained was a man stripped of audience, applause, and illusion.

That loss is the condition of the book.

De Profundis is not a manifesto. It is not a defence. It is not even, strictly speaking, a confession. It is a slow, painful dismantling of the identity Wilde had spent a lifetime constructing. For perhaps the first time, Wilde writes without the protection of irony.

“I was a man who stood in symbolic relations to the art and culture of my age.”

The sentence sounds grand, almost familiar. But it is immediately undercut by self-critique. Wilde recognises how much of his life was performance. He lived as spectacle. He confused admiration with love. Pleasure with meaning. The prison cell forces an accounting that no drawing room ever demanded.

Why did Wilde choose to write this letter? Because silence would have destroyed him faster than punishment. Prison stripped Wilde of everything except thought. Writing became the only space where he could confront the gap between who he had pretended to be and who he actually was.

De Profundis is addressed to Lord Alfred Douglas, but Douglas is not the true audience. Wilde is. The letter uses Douglas as a mirror to examine obsession, dependence, ego, and emotional immaturity. What makes the text extraordinary is that Wilde does not absolve himself. He understands his complicity.

“Where there is sorrow, there is holy ground.”

This line is often quoted reverently. It should be read cautiously. Wilde is not romanticising suffering. He is trying to give it meaning because meaning is the only thing prison cannot take away. Without meaning, suffering becomes annihilation.

Wilde’s greatest realisation in De Profundis is not about love or betrayal. It is about ego. He recognises that his devotion to pleasure and brilliance was also a refusal of discipline, humility, and responsibility. This recognition is devastating precisely because it comes too late to prevent ruin.

“I had been a man of pleasure, and I made pleasure my philosophy.”

This is not regret dressed as wisdom. It is diagnosis. Wilde understands that his life had been structured around aesthetic delight at the cost of moral seriousness. Writing the letter allows him to articulate that imbalance without disguise.

What did Wilde gain from writing De Profundis?

He did not regain freedom. He did not regain reputation. He did not regain health. What he gained was self-knowledge without performance. For a man whose entire identity had been shaped around being seen, this was radical.

The Wilde who writes De Profundis is quieter, slower, more vulnerable. He begins to understand suffering not as theatrical tragedy but as education. This does not make him noble. It makes him honest.

One of the most striking elements of the text is Wilde’s rethinking of Christ. He reimagines Christ not as moral judge, but as artist of compassion, someone who valued individual experience over law. This interpretation reveals Wilde’s attempt to reconcile his aesthetic instincts with ethical depth.

“Christ’s place indeed is with the poets.”

This is Wilde trying to build a bridge between who he was and who he is becoming. Writing the letter allows him to integrate art and suffering instead of choosing one over the other.

For readers, De Profundis is unsettling. It offers none of the Wilde they expect. No epigrams. No clever inversions. No social sparkle. That disappointment is intentional. Wilde is refusing to perform even one last time.

For Wilde himself, the act of writing was stabilising. It imposed structure on despair. It allowed him to narrate his fall not as meaningless humiliation, but as transformation. Whether that transformation was complete is irrelevant. What matters is that it began on the page.

After prison, Wilde would never fully recover. The Ballad of Reading Gaol carries forward some of the clarity gained here, but the brilliance never returns in the same way. De Profundis marks the moment when Wilde stops trying to be dazzling and starts trying to be true.

This book belongs in this scroll because it did not refine Wilde’s craft for readers. It dismantled Wilde’s self-deception for himself.

He wrote to survive disgrace without losing coherence.

The reader receives the honesty as aftermath.

Sylvia Plath – The Bell Jar

She wrote to name the fracture.

Sylvia Plath did not write The Bell Jar to explain depression, critique patriarchy, or dramatize youth. Those readings came later. She wrote the novel to recognize herself while she still could. By the early 1960s, Plath had lived through a severe mental breakdown, electroconvulsive therapy, institutionalization, a volatile marriage, and a constant battle between brilliance and despair. Silence, for her, was not neutral. It was lethal.

The Bell Jar, published in 1963 under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas in the UK, is often mistaken for a roman à clef meant to shock readers with autobiography. That misses the point. The novel is not a diary. It is a controlled reconstruction of psychological collapse. Plath did not pour herself onto the page. She shaped chaos into narrative so it could be seen, named, and held at a distance.

“I felt myself melting into the shadows like the negative of a person I’d never seen before.”

Esther Greenwood is not Sylvia Plath. But she is the version of Plath who survived long enough to speak. The novel charts Esther’s descent into paralysis not as melodrama, but as erosion. Ambition turns hollow. Language loses traction. Identity fractures under expectation. Plath refuses grand gestures. The horror lies in banality.

Why did Plath choose fiction rather than memoir? Because fiction offered control. Plath was acutely aware of how women’s pain was dismissed as hysteria or sentimentality. Fiction allowed her to present mental illness without pleading for belief. The narrative does not ask for sympathy. It asserts reality.

“Wherever I sat—on the deck of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok—I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air.”

This metaphor is the novel’s core achievement. Depression is not sadness. It is enclosure. The bell jar distorts perception while appearing invisible from the outside. Plath gives language to something that resists language. That act alone is stabilizing.

Plath chose this topic because she needed to understand what had happened to her without drowning in it again. Writing the novel was not catharsis. It was containment. By transforming lived terror into structured narrative, she reduced its power. The book does not cure Esther. It explains her.

This distinction is crucial.

The Bell Jar does not end in triumph. Recovery is tentative, conditional, uncertain. That uncertainty is honest. Plath refuses the lie of closure because she knew better than anyone that mental illness does not obey narrative arcs.

“How did I know that someday—at college, in Europe, somewhere, anywhere—the bell jar, with its stifling distortions, wouldn’t descend again?”

This is not pessimism. It is vigilance. Writing the book allowed Plath to articulate the rules of her own survival. Awareness becomes defense.

Now the uncomfortable truth: The Bell Jar did not save Sylvia Plath’s life. She died by suicide shortly after its publication. This fact is often used to diminish the book’s significance or to romanticize her suffering. Both responses are lazy.

The purpose of writing is not always rescue. Sometimes it is clarity.

What did Plath gain from writing The Bell Jar?

She gained precision. The ability to say, “This is what it feels like,” without metaphor collapsing into melodrama. She gained authority over her own narrative at a time when doctors, husbands, and institutions were eager to define her experience for her. She gained a voice that did not ask permission to exist.

For readers, the book became a landmark text on mental illness, femininity, and identity. For Plath, it was something else entirely: a map of a dangerous terrain she had already crossed once and might cross again.

Writing the novel allowed her to externalize the fracture. To see it. To name it. To stop mistaking it for moral failure.

“I am, I am, I am.”

This line appears near the end of the novel, quiet but defiant. It is not optimism. It is assertion. Existence, claimed without explanation.

The Bell Jar belongs in this scroll not because it transformed readers’ understanding of depression, though it did. It belongs here because it represents writing at the edge of endurance. Writing not as triumph, but as temporary stabilization.

Plath did not write to inspire.

She wrote to understand the shape of her own danger.

That understanding mattered. Even if it was not enough.

Simone de Beauvoir – Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter

She wrote to think herself into freedom.

Simone de Beauvoir did not write Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter to confess, justify, or charm. She wrote it to understand how obedience is manufactured and how a thinking woman learns to outgrow it. This is not an autobiography driven by nostalgia. It is an intellectual audit. Beauvoir looks back not to soften the past, but to interrogate it.

Published in 1958, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter is the first volume of Beauvoir’s autobiographical project. The title itself is ironic, almost surgical. Beauvoir was dutiful. Excessively so. That is precisely the problem she sets out to examine. How does a girl raised to be intelligent, moral, disciplined, and respectable become trapped by those very virtues? And how does she escape without becoming incoherent or bitter?

“I did not like authority, but I liked being admired.”

That line alone explains why Beauvoir chose autobiography as her form. This is not self-celebration. It is self-exposure without sentimentality. Beauvoir dissects her childhood, education, religious devotion, and early ambitions to understand how a compliant girl became a woman capable of refusing every script offered to her.

Why did Beauvoir write this book? Because freedom, for her, was not instinctive. It had to be thought into existence.

Raised in a conservative bourgeois Catholic family in early twentieth-century France, Beauvoir was trained to be virtuous, disciplined, and deferential. Her intelligence was encouraged, but only within boundaries. Education was acceptable. Independence was not. Marriage was destiny. Motherhood was assumed. Beauvoir did not rebel dramatically. She complied brilliantly. And that brilliance almost destroyed her.

Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter traces the slow, often painful realization that obedience can coexist with ambition while quietly suffocating it. Beauvoir does not portray herself as oppressed by cruelty. She was oppressed by expectations delivered with affection.

“I was being trained for submission, and I did not yet know it.”

This is the central insight of the memoir. Beauvoir understood that domination does not always arrive with violence. Often it arrives as instruction. As care. As protection. Writing this book allowed her to name that process retroactively, to see how her early moral training had been designed to produce a particular kind of woman: thoughtful, refined, and safely contained.

Beauvoir chose memoir rather than philosophy because philosophy alone could not account for formation. Existentialism asks how one becomes free. The memoir asks why one wasn’t free to begin with. Writing her life allowed Beauvoir to bridge theory and experience.

This is where the book functions primarily for the writer, not the reader.

What did Beauvoir gain from writing Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter? Narrative coherence.

Before the memoir, Beauvoir’s life could be read as contradiction: devout Catholic turned atheist, obedient daughter turned radical thinker, respectable intellectual turned unconventional partner. Writing the memoir allowed her to see these not as betrayals, but as developments. Freedom did not appear suddenly. It was assembled through resistance, reading, friendship, and intellectual courage.

Her relationship with Sartre, so often sensationalized, appears here not as romance but as alliance. Beauvoir frames it as a deliberate refusal of inherited scripts. Writing the memoir allowed her to position that refusal as rational choice rather than scandal.

“I had been taught to aim at perfection; I was learning to aim at truth.”

That sentence could serve as the book’s thesis. Beauvoir is not interested in innocence. She is interested in lucidity. The memoir becomes a space where she can examine her complicity in her own confinement without self-loathing. That balance is rare.

For readers, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter offers insight into the making of a feminist philosopher. For Beauvoir, it offered something more urgent: release from false coherence. She no longer had to pretend that her past was seamless. Writing allowed her to acknowledge fracture without shame.

This is why the memoir matters within this scroll. Beauvoir did not write it to instruct women how to be free. She wrote it to understand how she herself had nearly failed to be.

Freedom, in Beauvoir’s vision, is not rebellion for its own sake. It is responsibility for one’s own becoming. Writing the memoir allowed her to claim that responsibility fully, without nostalgia, without apology.

The book did not change society overnight.

It changed Beauvoir’s relationship to her own formation.

She wrote to think herself into freedom.

The reader inherits the clarity.

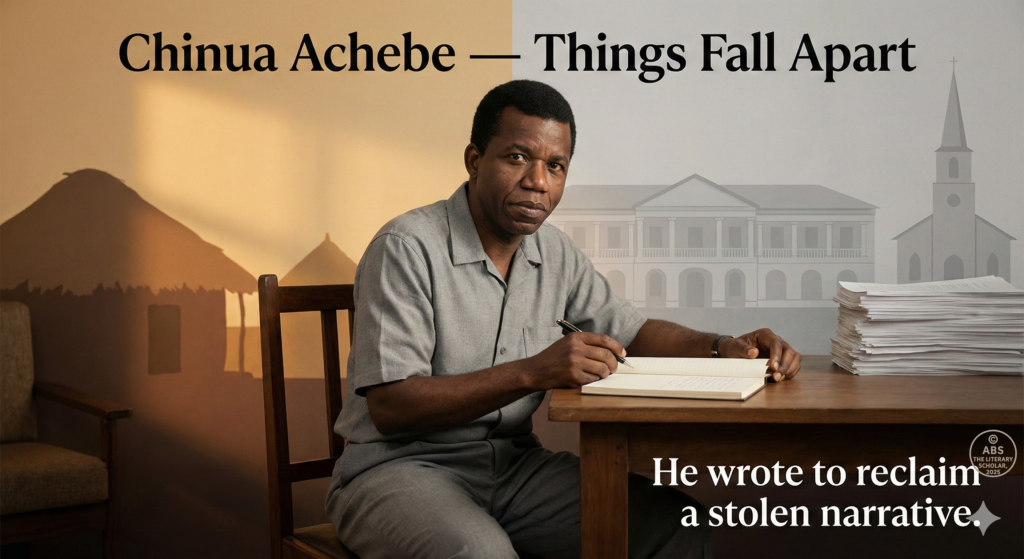

Chinua Achebe – Things Fall Apart

He wrote to reclaim a stolen inheritance.

This book did not change colonial history overnight.

It changed Achebe’s relationship with language, ancestry, and narrative authority. That is exactly why it belongs here.

Chinua Achebe did not write Things Fall Apart to entertain the West or explain Africa politely. He wrote it because the story of his world had already been written without him. And badly. Africa had been rendered either silent or grotesque, its cultures flattened into footnotes of empire. Achebe understood that if this misrepresentation went unchallenged, it would not merely insult the past. It would poison the future.

Writing, for Achebe, was not rebellion in the dramatic sense. It was correction.

“Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

Achebe chose fiction deliberately. History books had already failed him. Colonial anthropology had already distorted his inheritance. Fiction allowed him to rebuild Igbo life from the inside, not as spectacle, but as structure: rituals, kinship, law, masculinity, failure, pride. This was not nostalgia. It was reclamation.

Why did Achebe need to write this book?

Because inheritance had been interrupted.

Colonialism did not only conquer land. It fractured continuity. Languages were displaced. Values were caricatured. Achebe saw the danger clearly: if a people internalize a false story about themselves long enough, it becomes identity. Writing Things Fall Apart was his refusal to let that happen.

“The white man is very clever… He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart.”

This is not rage. It is diagnosis.

Achebe does not romanticize precolonial life. That restraint is crucial. Okonkwo is not a hero. He is rigid, violent, fearful of weakness. Achebe allows flaws to exist because truth, not pride, is the goal. Writing becomes an act of moral seriousness rather than defensive celebration.

What did Achebe gain from this book?

He gained narrative authority.

Before Things Fall Apart, Africa appeared in English literature largely as backdrop. After it, Africa spoke. More importantly, Achebe resolved his own tension with English. Instead of rejecting the colonizer’s language, he repurposed it. He bent English to Igbo rhythms, proverbs, and silences. That act alone was transformative.

For readers, the novel reframed colonial history.

For Achebe, it did something more intimate: it allowed him to stand inside his inheritance without apology, bitterness, or mimicry.

This is why the book sits here in the scroll.

After collapse comes refusal.

Not innocence. Not rage. Control.

Achebe did not inherit bitterness.

He inherited responsibility.

And he answered it with clarity.

What These Books Were Really Doing

By now, one thing should be clear.

These books were not written with readers in mind. At least not first.

Kamala Das was not trying to liberate Indian womanhood. She was trying to breathe.

Plath was not offering a case study in depression. She was mapping a danger zone.

Woolf was not writing a manifesto. She was designing mental architecture.

Proust was not indulging memory. He was reconstructing identity.

Rousseau was not confessing. He was defending his right to exist.

Dostoevsky was not explaining philosophy. He was fighting simplification.

Wilde was not performing tragedy. He was dismantling a persona.

Baldwin was not preaching reform. He was disciplining rage.

Beauvoir was not rebelling theatrically. She was thinking her way out.

Achebe was not correcting history politely. He was reclaiming a stolen voice.

The pattern is unmistakable.

Writing, at its most serious, is not communication.

It is self-negotiation.

Only after the writer stabilises, clarifies, confronts, or rescues something within themselves does the book become available to the reader. Influence is an after-effect. Survival is the origin.

This is where we misunderstand literature most deeply. We ask what books do to society, to students, to movements, to history. Rarely do we ask what they did to the person who wrote them at the moment of writing, when the outcome was uncertain and the cost was personal.

These writers were not brave because they told the truth.

They were brave because they told it without guarantees.

No assurance of praise.

No promise of understanding.

No certainty of survival beyond the page.

And yet, they wrote.

Not because writing is noble.

But because, for them, it was necessary.

The reader benefits. That is real.

But the writer needed it first.

That is the quiet truth this scroll insists on.

Some books change the world.

Some books change the reader.

But the most dangerous ones are those that change the writer enough to keep them alive, lucid, or free.

Those books do not announce themselves.

They arrive looking like literature.

But they were born as lifelines.

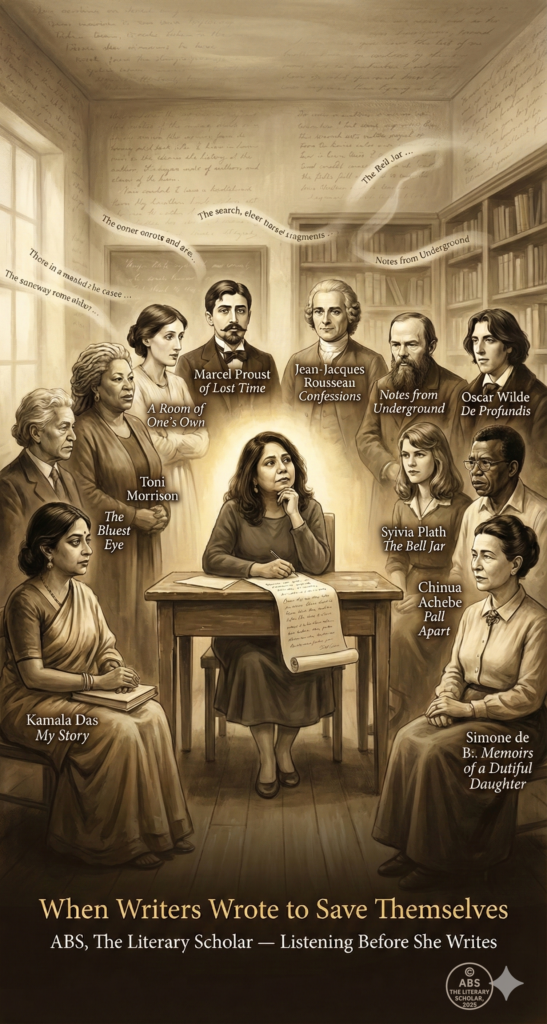

ABS pauses at the end of the scroll, not because the argument is complete, but because it has done its work. Writing about these books has not felt like commentary; it has felt like company. Each writer arrived with a different urgency, a different wound, a different necessity, and somewhere along the way, the act of reading them closely and then writing about them has quietly altered her own stance as a reader and a thinker. These books were written to save their authors, but they do not stop there. They insist that writing is never neutral, that reading is never passive, that thought itself is a form of responsibility. ABS realises that this scroll has fed her as much as it might feed the reader—not with answers, but with sharper questions. What does one write to survive? What does one refuse to inherit? What silences does one correct simply by choosing to speak clearly? She sees now that criticism, when done honestly, is not distance but participation. It is entering another mind long enough to come back changed. Slowly, without ceremony, she gathers the pages. Kamala Das breathing through confession. Morrison correcting absence. Woolf guarding mental space. Proust rebuilding time. Rousseau arguing for existence. Dostoevsky refusing simplification. Wilde dismantling the mask. Plath naming the fracture. Baldwin disciplining rage. Beauvoir thinking herself free. ABS folds the scroll gently, not as an ending, but as an acknowledgment—some books are written to change the world, but the most necessary ones are written so that someone, somewhere, can remain whole long enough to keep thinking.

Abha Bhardwaj Sharma is a Professor of English Literature with over 25 years of teaching experience. She is the founder of Miracle English Language and Literature Institute and the author of more than 50 books on literature, language, and self-development. Through The Literary Scholar, she shares insightful, witty, and deeply reflective explorations of world literature.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance