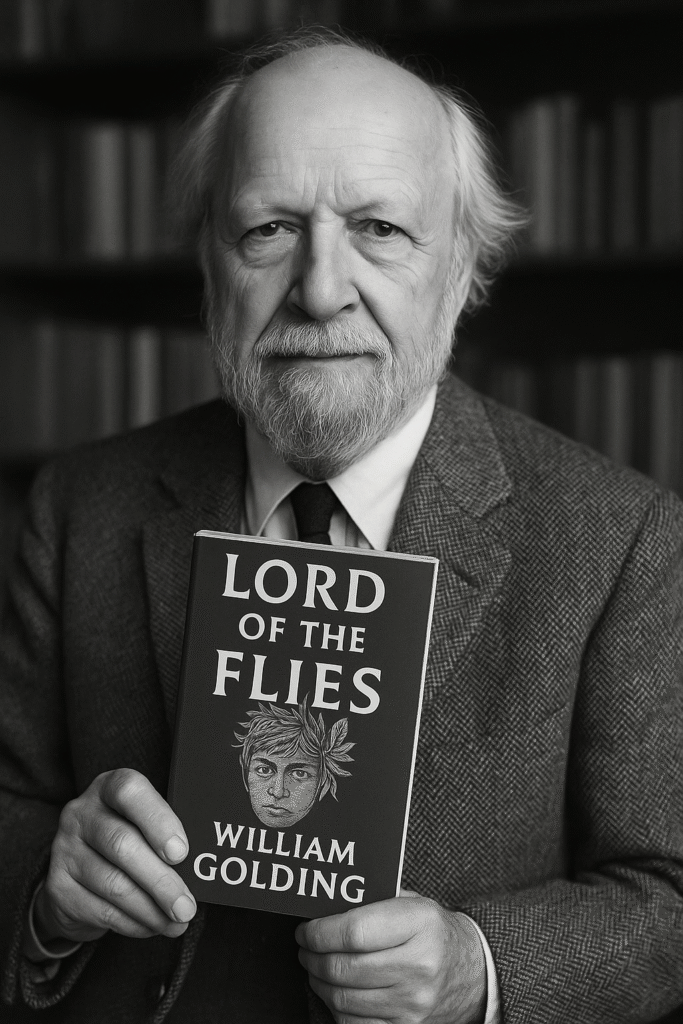

By ABS, The Literary Scholar

(Who firmly believes that giving a bunch of unsupervised British schoolboys a conch and some coconuts is not a social experiment—it’s a horror story waiting for footnotes)

Somewhere in the literary wild, past the pipe-smoking headmasters and the crisply ironed uniforms, lies a novel that dared to ask: What if we ditched all the grown-ups, stranded a plane full of choirboys on a tropical island, and watched the future of civilization eat itself alive?

Welcome to William Golding’s Lord of the Flies—a book that proves two eternal truths:

Children are not inherently innocent.

Conch shells do not come with user manuals for governance.

Written in 1954, in the golden post-war glow of British denial, Golding didn’t just write a story about boys on an island. He wrote a diagnosis. A bleak, hilarious, brutal x-ray of what happens when the thin skin of civility is scratched—and what bleeds out isn’t freedom, but chaos in shorts.

The Setup: Plane Crash + British Politeness = Delayed Apocalypse

A group of schoolboys crashes onto a remote island. No adults. No rules. Just jungle, sunburn, and one majestic conch shell, which becomes their version of a constitution—because what else screams democracy like seashells?

At first, things look promising. Ralph is elected leader because he’s blonde and can blow the conch well (which is apparently enough for a political career). Piggy—overweight, asthmatic, and intellectually superior—is ignored, mocked, and instantly used as a footnote.

“What intelligence had been shown was traceable to Piggy…”

(…but let’s bully him anyway, shall we?)

And then there’s Jack—red-haired, rage-filled, and two missed meals away from inventing fascism with face paint.

Together, they build shelters, form committees, and try to maintain a signal fire.

It lasts exactly three chapters.

From Choirboys to Cannibals: A Timeline of Rapid Degeneration

Golding does not drag his readers through slow decay. No, he lights the bonfire early—and throws logic, morality, and group projects straight in.

Fire goes out because hunting pigs is more fun than getting rescued.

Beast sightings increase, because fear needs no evidence—just imagination.

Face paint appears, and Jack declares the birth of “the hunters,” as if they’ve just formed a very stabby boy band.

Piggy’s glasses are stolen, because democracy is cute until you need fire, and then optics literally matter.

And soon enough: there are chants. Dances. Spears. Sacrifices.

By the halfway point, these children have invented their own religion, political system, and execution ritual. Freud would’ve fainted by page 90.

Piggy: The Intellectual Nobody Listens To (Until It’s Too Late)

Piggy is the heart of the novel’s irony. He sees everything clearly. He wants to build shelters, maintain hygiene, and maybe not chase each other with spears. Naturally, he’s laughed at and eventually killed by a rock—because metaphors come with gravity.

“Which is better—to have rules and agree, or to hunt and kill?”

That’s Piggy’s final plea. The answer? A boulder to the head. Civilization ends not with a bang, but with a squeal and a shattering of spectacles.

Simon: The Quiet Prophet (and First Martyr of Fear)

And then there’s Simon—the gentle, epileptic visionary who speaks to the “Lord of the Flies”, a pig’s head on a stick, swarming with flies and buzzing with malevolence.

“Fancy thinking the Beast was something you could hunt and kill! You knew, didn’t you? I’m part of you?”

Simon realizes what the others won’t: the beast isn’t in the jungle. It’s in them. It’s fear. Rage. The unspoken violence under every rulebook.

So naturally, they stab him to death during a tribal frenzy, mistaking him for the beast. Because of course.

Jack Merridew: Dictator in Shorts

Let’s not beat around the fire pit: Jack is every failed revolutionary who burns democracy to roast a pig.

He rejects rules. He steals fire. He speaks only in commands. And he loves the power of spectacle—face paint, dancing, chanting, and a loyal band of savages who never ask about quarterly performance reviews.

Jack doesn’t want freedom. He wants followers. Preferably ones who sharpen sticks at both ends.

Ralph: The Tragic Center Who Believed in Order

Poor Ralph. He tried. Really, he did. He believed in conches, and votes, and keeping the fire going. He believed boys could organize like Parliament and not like Lord of the Flies.

But Ralph forgets what Golding knows too well: Without institutions to back it, morality is just wishful thinking in khaki shorts.

By the end, Ralph is alone, hunted, feral, and clutching the shattered remnants of civilization. The signal fire he once nurtured now becomes the island’s funeral pyre.

And Then—A Naval Officer Appears

Just as Ralph is about to be hunted down like wild game, a British naval officer arrives.

He sees the smoke, the dirt-smeared boys, the dead bodies.

And what does he say?

“I should have thought that a pack of British boys would have been able to put up a better show than that.”

Ah yes. The colonial tsk-tsk of disappointment. Not at the murder, but at the lack of decorum.

Civilization, after all, must look proper—even in its collapse.

So What Was Golding Trying to Say?

A lot. And none of it reassuring.

Golding was a schoolteacher and a war veteran. He didn’t believe in noble savages or pure innocence. He believed people—especially children—harbored darkness that only society held in check.

And when society vanished? That darkness sang. Danced. Hunted. Speared.

“Maybe there is a beast… maybe it’s only us.”

And somewhere, ABS, The Literary Scholar, picks up the conch, finds it cracked, hands it back to the sand, and murmurs, “The rules of the game were always optional. We just pretended they weren’t.”

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

(Who no longer trusts islands, boys’ choirs, or conch-based governance systems)

(Still lighting signal fires in the pages of banned books)

(And who knows that every civilization is just one lost adult away from a bonfire)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance