By ABS, The Literary Scholar

(Who firmly believes that every woman needs a room, a lock, and a polite sign that says “Not now, I’m writing history.”)

Before coworking cafes and aesthetically filtered writing retreats… before motivational mugs and #BossLady hashtags… before anyone thought of monetizing silence… there was Virginia Woolf, walking across a cloistered university lawn, stopped by a beadle for trespassing on patriarchal turf, and thinking, What if a woman just had a room?

Not just a literal room. A space. A place to think, to write, to rage, to rest, to invent new literary forms—or at least close the door on laundry and mansplaining.

Thus was born A Room of One’s Own (1929)—part essay, part extended lecture, and part polite, searing, post-Edwardian thunderclap. It is Woolf’s beautifully frustrated answer to the question: Why have there been no great women writers?

Her reply? They were too busy folding your socks, dying in childbirth, or being denied access to the library.

Woolf’s Premise: Money and a Room Are Not Luxuries—They’re Survival Tools

Woolf begins by saying she can’t give us one tidy answer to women and fiction. Instead, she will “wander”—and wander she does, from Oxbridge gardens to Shakespeare’s imaginary sister to the painfully short shelf of women’s literature in the British Museum.

Her thesis, however, is sharp:

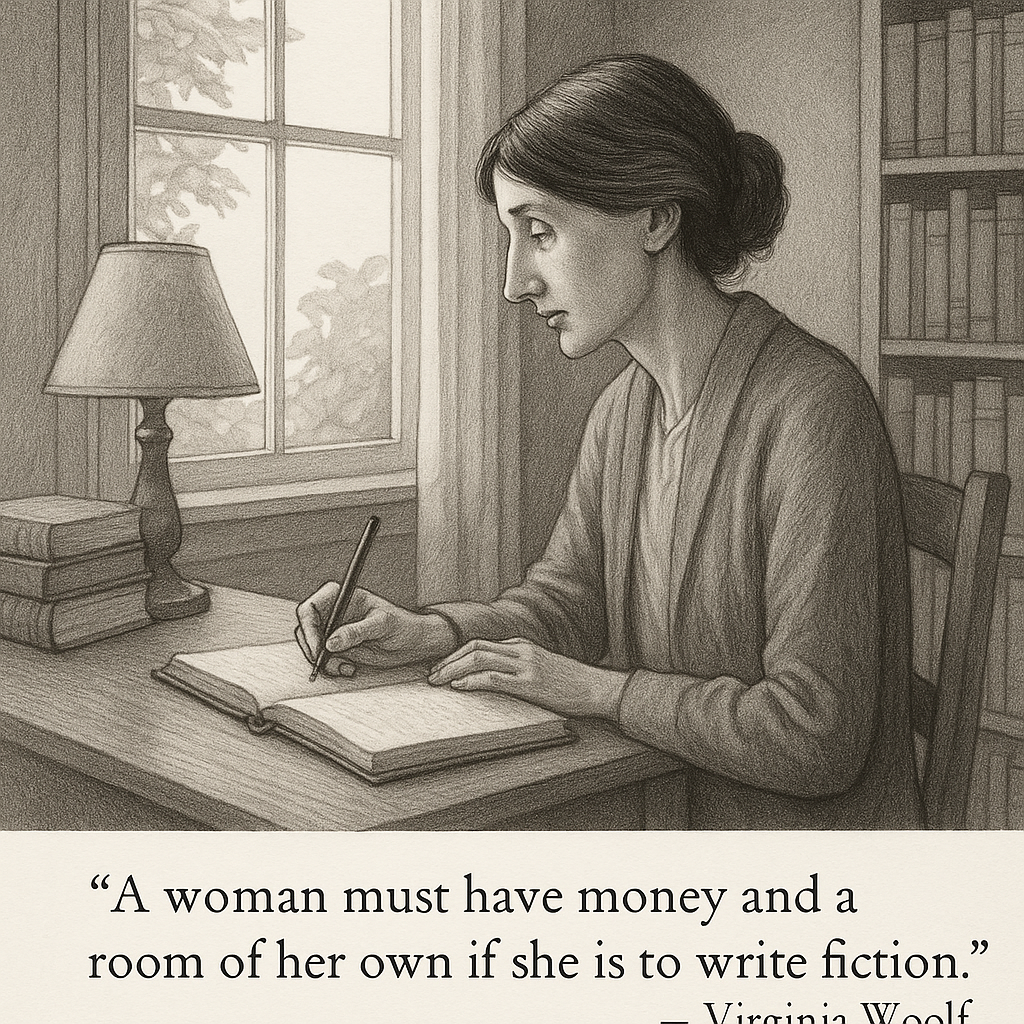

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

Not talent. Not ambition. Not divine inspiration.

Money. And space.

Because without economic independence and mental solitude, genius doesn’t grow. It shrivels between housework and humiliation.

Shakespeare’s Sister: A Thought Experiment That Deserves Its Own Play

Woolf asks us to imagine Judith Shakespeare, Will’s equally gifted sister. She’s denied education, mocked for reading, beaten for writing, and eventually dies alone in despair and obscurity. Her brilliance? Unpublished and unlit.

“She lies buried where the omnibuses now stop.”

It’s not just poetic. It’s devastating.

Woolf makes it clear: history didn’t forget women writers. It never gave them a chance to exist.

Patriarchal Publishing and the Literary Lodging Crisis

In her slow-burn sarcasm, Woolf walks us through the fate of female authors past:

Aphra Behn wrote to survive.

Charlotte Brontë wrote through mental claustrophobia.

Jane Austen wrote in drawing rooms, concealing her manuscripts when guests arrived.

Emily Brontë wrote Wuthering Heights like a woman possessed—and was punished for it.

And all of them, Woolf notes, had to squeeze genius into someone else’s space.

“Literature is open to everybody. But it is not open on equal terms.”

Cue generations of gatekeeping disguised as taste.

The Male Critic as a Literary Traffic Cop

Woolf takes an extended and glorious detour into how men write about women. And it’s… not flattering.

“Imaginatively, she is of the highest importance; practically, she is completely insignificant.”

Men write women as muses, mothers, saints, sinners, temptresses—but never thinkers. Never equals. Never the ones telling the story.

In short, women exist as narrative decoration. Essential to the plot. Excluded from the pen.

Woolf’s critique is razor-sharp, but never shrill. She doesn’t shout. She eviscerates gently, like a surgeon with lace gloves.

Androgyny and the Art of Being Two Things at Once

In a delightfully strange and daring turn, Woolf introduces the idea that the best minds are androgynous. Not biologically, but imaginatively.

A great writer, she argues, fuses the masculine and feminine within—writes not from gendered grievance, but from balance.

“It is fatal to be a man or a woman pure and simple; one must be woman-manly or man-womanly.”

This isn’t a cop-out. It’s a challenge. Woolf isn’t asking women to erase their experience—she’s asking all writers to outgrow their egos.

The Library: A Metaphor with Locked Doors

Woolf spends a haunting moment at the British Museum, observing the sheer disparity in what has been preserved, published, and discussed.

A man writing about women is history.

A woman writing about herself is “domestic.”

This imbalance is not a flaw. It is a system. And Woolf doesn’t beg for inclusion—she demands reinvention.

The canon, she implies, needs new wings. And possibly a few wrecking balls.

Woolf’s Legacy: From Drawing Rooms to Digital Desks

A century later, Woolf’s words are still tattooed in the margins of every woman trying to write, think, or create while juggling rent, self-doubt, and society’s to-do list.

Yes, more women write now.

Yes, more rooms exist.

But the struggle for space—mental, emotional, economic—isn’t history. It’s still happening.

“Lock the door,” Woolf whispers.

“Then write like the house isn’t burning.”

And somewhere, ABS, The Literary Scholar, closes the door softly, rearranges a vase beside a coffee-stained notebook, lights a lamp, and scribbles in the corner of the page: “This is my room. And I refuse to share it with the patriarchy.”

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

(Who believes the rent is never just rent when you’re trying to write a revolution)

(Still rearranging mental furniture to make space for unsanctioned thoughts)

(And who knows that Woolf didn’t just ask for a room—she built one, and handed us the key)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance

Hi, I enjoyed this Virginia Woolf piece – but as a professor emeritus myself bout to lead some sessions on feminism, I can’t include a reference with no sense of your identity. m I not looking deeply enough into your website? Or, Are you not publishing your name and credentials, background/ etc. The anonymity of social media is not my jam. Thanks for a reply in advance.

Dear Professor Lynn Carrigan,

Thank you so much for reaching out. I have shared a detailed reply with all the information in your email. I hope you find it helpful and interesting.