Fiction Becomes the Mirror of Society (1840s–1880s)

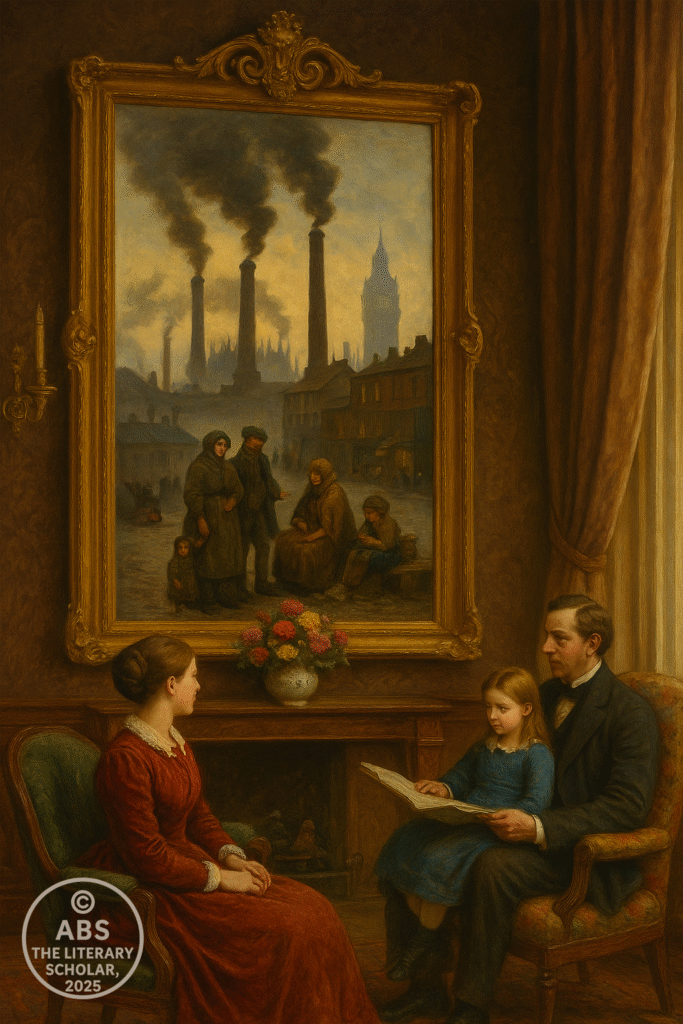

From The Professor's Desk

The Victorian Age of Fiction: When the Novel Found Its Voice

The voice of the poet had opened the Victorian Age with grandeur, grief, and doubt.

In the resonant cadences of Tennyson, the brooding ironies of Browning, the spiritual melancholy of Arnold, and the moral passion of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Victorian England heard its conscience struggling to speak. But as the century deepened, and the tempo of social and industrial change accelerated, it became clear that verse alone could no longer contain the full complexity of modern life.

Poetry had shaped the Victorian imagination; it had awakened the age to its moral contradictions and spiritual anxieties. Yet poetry, for all its power, was a form too rarefied, too limited in scope to encompass the teeming realities of industrial cities, the subtle textures of social life, and the intricate play of psychological motives that now demanded exploration.

Thus emerged the Victorian Age of Fiction—a time when the novel rose not merely as entertainment, but as a moral and social force. The Victorian world, with its vast new middle-class readership, its hunger for narrative, and its fascination with progress and reform, required a new instrument. And so, the Victorian novel rose to prominence—not to replace poetry, but to extend its moral mission into the dense fabric of society itself.

If the poet was the seer of the age, the novelist became its anatomist.

Through the long, unfolding architecture of narrative, the Victorian novelist could portray the clash of classes, the constraints of gender, the grip of poverty, the hypocrisies of respectability—and the quiet heroism of ordinary lives struggling toward meaning.

In the hands of masters like Charles Dickens, George Eliot, the Brontë sisters, and William Makepeace Thackeray, fiction became the chief vehicle through which Victorian England examined its own soul. It was a mirror—but a mirror held up not to idealize, but to confront—sometimes harshly, sometimes tenderly—the realities of an age both triumphant and tormented.

It is to this extraordinary flowering of the Victorian Age of Fiction that we now turn—where the great moral and imaginative energies of the century found their most expansive, enduring expression. The poet had sung; the storyteller now speaks.

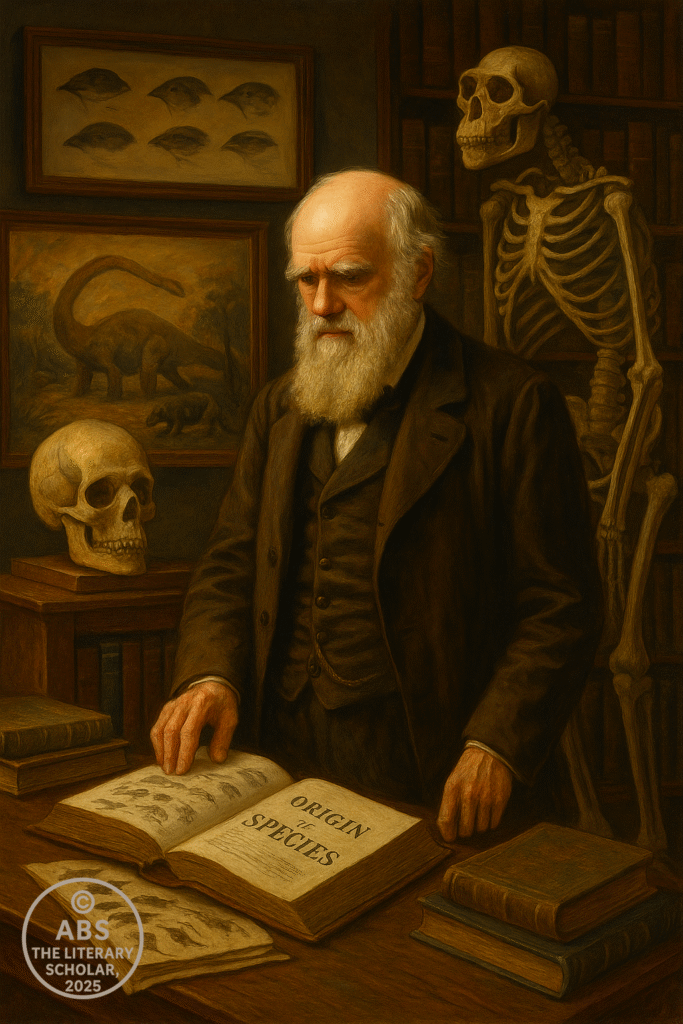

Charles Darwin and his On The Origin Of Species (1859)

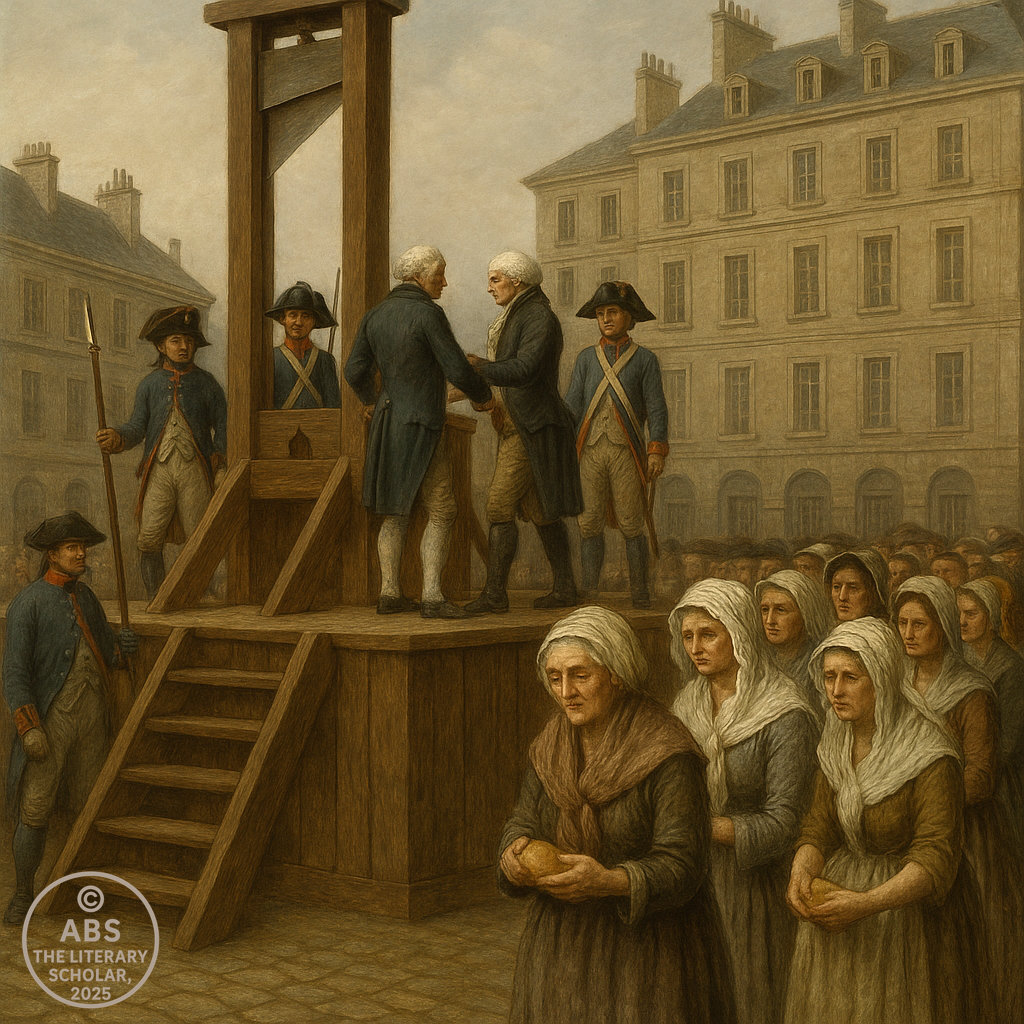

Amidst these currents of moral and social change, the Victorian imagination was shaken by one of the most momentous scientific revelations of the age. In 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species—a work that would alter not only the sciences but the very intellectual fabric of Victorian thought. Darwin’s theory of natural selection—that life evolved through the gradual adaptation of species to their environments, with survival favoring the fittest—challenged traditional religious narratives of divine creation and teleological purpose.

The impact of Darwin’s ideas rippled swiftly into the moral and literary consciousness of the time. Novelists, more than poets, proved keenly responsive to this shifting worldview. The concept of struggle, adaptation, and the sometimes pitiless workings of chance and necessity found echoes in the plots and moral conflicts of Victorian fiction. Dickens’s London, teeming with the vulnerable and the ruthless; Eliot’s Middlemarch, charting the delicate interplay of choice and social constraint; the Brontës’ fierce portrayals of passion battling social forces—all bear traces of a new understanding of life as an arena of conflict, contingency, and evolution. The novel, with its capacious form, proved uniquely suited to explore the human meanings of a world no longer governed by providence alone, but by the inexorable processes of nature and history.

The Rise of the Victorian Novel — Fiction as Moral Mirror

By the mid-nineteenth century, the novel had become the chief vessel of England’s moral imagination.

It is easy to forget that this was not always so. For much of the previous century, prose fiction had stood on the margins of cultural respectability. Verse was the medium of genius; novels, when not dismissed as trivial, were tolerated as mere entertainment for women and tradespeople. The serious reader turned to poetry or history; the novel was considered a lesser form.

But in the furnace of the Victorian age—shaped by the twin pressures of industrial transformation and moral anxiety—the novel claimed its place at the center of literary culture. It did so not by abandoning entertainment, but by fusing narrative pleasure with social conscience. The Victorian novel became both mirror and lamp: reflecting the conditions of the age, and illuminating the ethical questions that those conditions raised.

Poetry had opened the age in lofty tones, but the novel answered with breadth and depth.

Where a lyric might express personal grief, and an epic might evoke heroic virtue, the novel could enter the dirty factories of Manchester, the drawing rooms of Mayfair, the schools of Yorkshire, the courts and parliaments of London, and the cottages of the countryside. It could track the intricate flow of daily life and expose the moral failings that respectable society sought to conceal.

It is no accident that this transformation coincided with the rise of the Victorian middle class. The political and economic power of this new class demanded a literature in its own image: realistic, broadly accessible, concerned with social order, family values, and individual moral progress. Poetry, in its elevated diction and arcane traditions, seemed too remote. The novel offered a more intimate, democratic art—one that could speak directly to the concerns of ordinary readers.

The mechanism of publication accelerated this shift. Serial publication, made popular through magazines and periodicals, allowed novels to reach an audience far beyond the leisured elite. The experience of reading a novel week by week, often aloud in the family circle, became a defining ritual of Victorian domestic life. Lending libraries, such as Mudie’s Select Library, further democratized access to fiction, while also exerting a powerful influence on its content: novels had to be “safe” for female readers and respectable families—hence the persistent tensions between realism and moral propriety that characterize the Victorian novel.

But it was not merely the audience that transformed the novel; it was the novelists themselves. The great writers of the age approached fiction not as a diversion, but as a moral enterprise. Dickens, Eliot, the Brontës, Thackeray—each in their own way sought to explore the moral life of their society, to expose its hypocrisies, and to imagine forms of redemption. Their novels are, in this sense, novels of conscience.

“The novel is the only literary form capable of fully representing modern life,” George Eliot once remarked. And modern life, in Victorian England, was a life of searing contradictions: unprecedented wealth alongside abject poverty, scientific progress eroding religious certainties, imperial triumph masking moral unease, the rise of individualism confronting the weight of social convention. The novel provided a canvas large enough to encompass these tensions, and to dramatize them through the fates of memorable characters.

The art of characterization became the Victorian novelist’s supreme gift. Where earlier fiction often trafficked in types and stock figures, the great Victorian novelists aspired to create characters as complex and morally ambiguous as real human beings. Dickens’s grotesques and eccentrics, Eliot’s painfully self-aware moral strivers, the Brontës’ tempestuous souls, Thackeray’s cynical social climbers—all live with an intensity that continues to grip modern readers.

In this expansion of character went an expansion of psychological realism. The Victorian novel plumbed the hidden motives of its protagonists, charted the evolution of their consciences, and explored the moral consequences of their actions. The novel became a laboratory for ethical inquiry, a means of posing the eternal questions: How should one live? What is justice? What does it mean to be good?

Yet even as it addressed these lofty questions, the Victorian novel remained grounded in the textures of the everyday. It is a literature that delights in the mundane and the particular—the manners of the parlour, the rituals of courtship, the grim realities of factory labor, the petty corruptions of local politics. Its greatness lies precisely in this ability to render the ordinary extraordinary, to find in the small lives of forgotten individuals the grand moral dramas of an entire age.

In becoming the moral mirror of Victorian society, the novel also became its most lasting art form. The poems of the age are often admired, but the novels are still devoured. They continue to speak to us because they grapple with human nature, in all its contradictions, with a depth and honesty that transcend their own time.

As we turn now to the individual voices of this golden age of fiction, we will see how each novelist shaped this moral mission in a unique style. In Dickens, we will find the prophetic satirist of social injustice; in George Eliot, the profound anatomist of conscience; in the Brontës, the fierce rebels of emotion and spirit; in Thackeray, the genial but unsparing observer of society’s vanities. Together, they created a literary legacy that still shapes how we see the world—and ourselves.

The poet had sung; now the novelist takes up the scroll. Let us follow its unfolding.

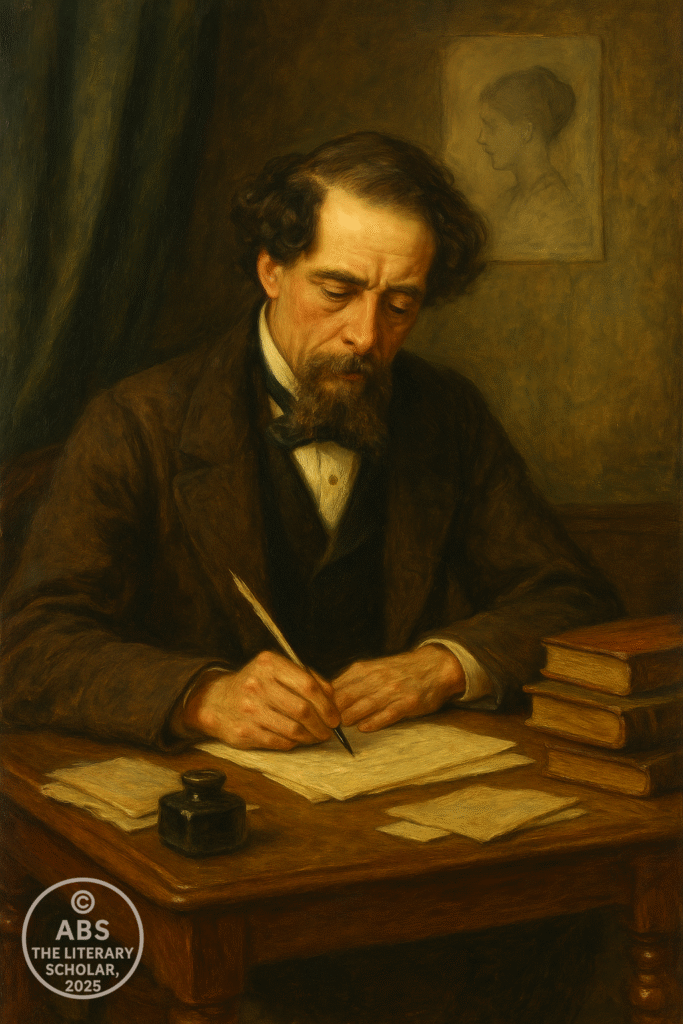

Charles Dickens — The Conscience of a Cruel Age

No writer captured the imagination—and the conscience—of Victorian England more fully than Charles Dickens.

To speak of the Victorian novel is, in one breath, to invoke his name. He was not the first great English novelist, nor the last; but he was the one who made the novel a national passion and a moral force. Through his astonishing gallery of characters and his relentless portrayal of social injustice, Dickens gave the British middle class its most vivid self-portrait—warts, virtues, contradictions, and all.

Born in 1812 in Portsmouth, Charles Dickens experienced, in his own boyhood, the bitter realities he would later dramatize in fiction. His father, a well-meaning but improvident man, landed in debtor’s prison, forcing the young Charles to work in a blacking factory—an experience of humiliation and despair that would leave permanent scars. “I might easily have been, for any care that was taken of me, a little robber or a little vagabond,” he later wrote. Out of this early trauma emerged a lifelong sensitivity to the sufferings of the poor and the voiceless, a passion that would animate all his fiction.

Dickens began his literary career as a journalist and sketch writer under the pseudonym Boz. His gift for observational detail and his instinct for character quickly became apparent. But it was with the serial publication of The Pickwick Papers (1836–37) that he became a public sensation. From that point onward, Dickens’s novels appeared first in monthly or weekly parts, consumed eagerly by an expanding middle-class readership. The serial form shaped Dickens’s narrative technique: he wrote with a keen sense of cliffhangers, dramatic reversals, and episodic structure, ensuring that his fiction unfolded with the pulse of popular life.

Yet Dickens was not merely a popular entertainer. He believed passionately that the novel should be a moral instrument—a means of awakening public conscience. “I have always striven hard to inculcate the principles of generosity and forgiveness, to soften the heart of the rich toward the poor,” he declared. The Victorian novel was, in his hands, a weapon of social critique, and he wielded it to unmask the hypocrisies and cruelties of an age that proclaimed Christian charity while tolerating grinding poverty, child exploitation, and institutional corruption.

The Art of Characterization

One of Dickens’s supreme gifts was his ability to create characters who live beyond the page. His novels teem with a vast array of figures—some grotesque, some comic, some tragic, all indelibly human. Dickens had a genius for the vivid physical detail, the catchphrase, the mannerism, that brings a character instantly to life.

Consider Uriah Heep in David Copperfield, with his writhing self-effacing humility—“I am a very umble person”—masking a soul of envy and deceit. Or Mr. Micawber, eternally optimistic amidst disaster, declaring “Something will turn up.” Or the spectral figure of Miss Havisham in Great Expectations, rotting in her bridal dress amid the decaying remnants of her thwarted hopes.

These characters are more than Dickensian quirks; they are symbols of moral conditions. Through them, Dickens explored the psychological effects of poverty, pride, resentment, greed, and forgiveness. His art of characterization was inseparable from his moral vision.

Oliver Twist — Child Exploitation Exposed

With Oliver Twist (1837–39), Dickens embarked on direct social critique. The novel exposes the horrors of workhouse life and the criminal underworld of London’s streets. Through the figure of Oliver—a child born in the parish workhouse—Dickens dramatized the systemic cruelty of the Poor Laws, which treated poverty not as a misfortune but as a moral failing.

The novel’s famous scene of Oliver asking for more—“Please, sir, I want some more.”—became an iconic image of institutional callousness. In Fagin, Bill Sikes, and Nancy, Dickens portrayed the moral complexities of the criminal underclass. Nancy’s tragic arc, torn between loyalty to Sikes and compassion for Oliver, remains one of Dickens’s finest achievements in moral ambiguity.

Through Oliver Twist, Dickens forced middle-class Victorian readers to confront the realities they preferred to ignore. The novel helped fuel debates about child labor, urban poverty, and criminal justice.

David Copperfield — The Personal and the Universal

David Copperfield (1849–50) is perhaps Dickens’s most beloved novel—and certainly his most personal. It draws deeply from his own life: the factory work, the feckless father, the humiliations of poverty. Yet the novel transcends autobiography to become a universal bildungsroman—a tale of a young man’s moral and emotional growth.

David’s journey is punctuated by a gallery of unforgettable figures—Peggotty, Barkis, Steerforth, Betsey Trotwood, Mr. Dick, Uriah Heep, Mr. Micawber—each embodying different facets of human nature and social experience.

At the heart of the novel is a profound meditation on character and fate: Can virtue triumph over adversity? Can forgiveness overcome betrayal? Can a society obsessed with appearances recognize genuine moral worth? Dickens’s answer is cautiously hopeful—but never sentimental.

Bleak House — Institutional Satire

With Bleak House (1852–53), Dickens achieved his most sophisticated social satire. The novel centers on the interminable lawsuit of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, a metaphor for the paralyzing inertia of the British legal system. Dickens’s portrait of Chancery Court is devastating:

“This is the Court of Chancery; which has its decaying houses and blighted lands in every shire; which has its worn-out lunatic in every madhouse, and its dead in every churchyard.”

The novel also marked a breakthrough in narrative technique. By alternating between omniscient narration and the first-person voice of Esther Summerson, Dickens created a layered perspective on the moral and institutional corruption of Victorian England.

Bleak House remains a masterpiece of structural complexity, moral indignation, and psychological realism—anticipating many of the innovations of the modern novel.

Hard Times — The Gospel of Utilitarianism Condemned

In Hard Times (1854), Dickens turned his gaze on the philosophy of utilitarianism—the doctrine that all decisions should be based on quantifiable outcomes and greatest happiness. In the fictional industrial city of Coketown, Dickens depicted a world stripped of imagination, compassion, and beauty.

Thomas Gradgrind, the apostle of fact, epitomizes this ideology:

“Facts alone are wanted in life.”

Through the moral collapse of Gradgrind’s own family, and the sufferings of factory workers like Stephen Blackpool, Dickens exposed the inhumanity of a purely mechanistic social order.

Hard Times is a briefer, more polemical novel—but its critique of industrial dehumanization remains chillingly relevant.

Great Expectations — The Ambiguities of Success

Great Expectations (1860–61) is one of Dickens’s most psychologically subtle works. Through the figure of Pip, the orphan who aspires to gentlemanly status, Dickens explored the corrupting power of money, the illusions of social ambition, and the redemptive force of loyalty and love.

The novel’s famous opening scene—the terrified Pip in the graveyard, seized by the convict Magwitch—is emblematic of Dickens’s genius for dramatic imagery. Yet the heart of the novel lies in its moral journey: Pip’s growing awareness of the false values he has embraced, and his ultimate reconciliation with the moral truths of loyalty, humility, and kindness.

The Enduring Legacy

Why does Dickens still matter?

Because his novels, for all their Victorian idiosyncrasies, speak to universal moral questions.

Because his characters, drawn with comic exuberance and psychological insight, continue to live in the reader’s imagination.

Because his critique of social injustice, institutional cruelty, and human hypocrisy remains urgently relevant.

Above all, Dickens believed in the power of storytelling as moral action. He wrote not merely to entertain, but to awaken the conscience of his age. In this, he succeeded beyond measure.

As we turn next to George Eliot, we shall encounter a different voice of the Victorian conscience—more inward, more subtle, yet equally profound. The novelist’s scroll continues to unfold.

George Eliot — The Depths of the Human Heart

If Dickens was the novelist of society’s conscience, George Eliot was the novelist of its inner life.

In her fiction, Victorian literature gained not only a new psychological depth, but a new seriousness of moral purpose—a vision that refused to divide life into simple contrasts of good and evil, and that sought instead to portray the subtle interweaving of motives, affections, errors, and ideals that shape the human soul.

Born Mary Ann Evans in 1819, Eliot was from the start an intellectual rebel. Raised in the rural Midlands, educated far beyond the expectations for a girl of her station, she absorbed the rich evangelical culture of her youth even as she grew restless with its theological constraints. The young Mary Ann became an avid reader of Enlightenment philosophy, German higher criticism, and the emerging human sciences—interests that would later saturate her fiction.

Her choice of the pseudonym “George Eliot” was both a defiance of Victorian gender norms and a shield against the scandal of her private life: she lived openly with George Henry Lewes, a married man, in a union that cost her much of the social acceptance her talent deserved. But if the drawing rooms of respectable London shunned her, the great minds of her age admired her profoundly. By the time of her death in 1880, George Eliot stood among the most respected writers in England—one who had raised the English novel to new heights of intellectual and moral complexity.

The Psychological Turn

Eliot’s deepest contribution to Victorian fiction was her insistence that character, not plot, must lie at the heart of the novel. For her, the task of fiction was not to construct elaborate adventures or melodramatic confrontations, but to explore the workings of the human mind and heart—how motives form, how sympathies grow or wither, how self-deception operates, how moral insight slowly emerges.

“The greatest benefit we owe to the artist, whether painter, poet, or novelist, is the extension of our sympathies,” she wrote. In this belief lies the essence of her art: she sought to make readers feel the moral weight of actions, to understand how small, unnoticed decisions shape destinies, and to cultivate an imaginative empathy for lives unlike their own.

This project required a narrative voice of unusual subtlety—and Eliot’s mature style is one of the great triumphs of Victorian prose: serious but never ponderous, capable of tender irony and moral passion, alert to both the tragic grandeur and the quiet pathos of ordinary life.

Adam Bede — The Drama of Rural Morality

Eliot’s first full-length novel, Adam Bede (1859), was an immediate success. Set in a vividly rendered Midlands village, the novel portrays the intertwined lives of its characters—chief among them Adam Bede, a virtuous carpenter; Hetty Sorrel, a vain and impulsive dairy maid; and Dinah Morris, a Methodist preacher.

At its heart, Adam Bede is a tragedy of self-deception and social cruelty. Hetty’s seduction and abandonment by Arthur Donnithorne, the local squire’s grandson, leads to catastrophe—not merely for Hetty herself, but for the entire moral fabric of the community. Eliot’s treatment of Hetty’s downfall is remarkable for its psychological depth and compassion; she refuses to vilify Hetty, presenting her instead as a young woman trapped by vanity, fear, and the limited horizons of her world.

Through the novel’s unfolding, Eliot explores themes that would recur throughout her fiction: the dangers of moral blindness, the complex interplay of individual and social forces, and the necessity of sympathy and moral growth. Adam Bede marked a new kind of realism in the English novel—one that valued the moral significance of ordinary lives.

The Mill on the Floss — Passion and Constraint

Eliot’s next major work, The Mill on the Floss (1860), remains one of her most personal and poignant novels. Its heroine, Maggie Tulliver, is among the most fully realized female characters in Victorian fiction—a passionate, intelligent girl whose hunger for life and love is constantly thwarted by social expectations and familial duty.

The novel is steeped in Eliot’s own memories of her Midlands childhood, and its pages shimmer with a profound nostalgia for lost innocence and a fierce critique of narrow provincial life. Yet its moral vision is never sentimental. The Tulliver family’s stubborn pride, petty resentments, and failure of empathy contribute as much to Maggie’s fate as the injustices of society do.

In The Mill on the Floss, Eliot’s mastery of psychological narrative reaches new heights. She shows, with devastating clarity, how small emotional wounds accumulate, how love can coexist with resentment, and how the noblest intentions can lead to unintended harm. Maggie’s final tragic embrace with her brother Tom—a moment of reconciliation too late to avert disaster—remains one of the most heartbreaking scenes in Victorian literature.

Middlemarch — The Great Victorian Novel

Middlemarch (1871–72), Eliot’s crowning achievement, is widely regarded as the greatest English novel of the nineteenth century. In its vast tapestry of provincial life, Eliot weaves together multiple narrative strands—political reform, scientific ambition, romantic aspiration, and spiritual yearning—with a depth of insight unmatched by her contemporaries.

At the center of the novel stands Dorothea Brooke, a young woman whose idealism and hunger for moral purpose lead her into a disastrous marriage with the pedantic scholar Casaubon. Through Dorothea’s gradual awakening to the complexities of human life, Eliot explores one of her central themes: the tragic gap between aspiration and reality.

Yet Middlemarch is not a novel of a single character. Its greatness lies in its portrayal of an entire community, rendered with extraordinary social and psychological detail. Figures like the ambitious doctor Lydgate, the shallow but charming Rosamond Vincy, and the steady-hearted Fred Vincy are drawn with such richness that the reader comes to know them as fully as real acquaintances.

Perhaps most striking is Eliot’s narrative stance: a voice that combines moral earnestness with ironic detachment, always seeking to understand rather than to condemn. Her famous closing tribute to Dorothea could apply to Eliot’s own art:

“The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

Moral Vision and Lasting Legacy

What distinguishes Eliot from even the greatest of her peers is her moral seriousness. She believed passionately that fiction should cultivate the reader’s capacity for empathy, self-knowledge, and moral reflection. Her novels are not sermons, but they are works of ethical imagination—inviting us to confront the moral ambiguities of life and to recognize our shared human frailty and dignity.

In an age often seduced by progress and prosperity, Eliot insisted that the true measure of civilization lay not in its achievements, but in the quality of its moral life—in the depth of its sympathies, the integrity of its relationships, the fidelity of its daily acts.

The modern psychological novel owes an incalculable debt to George Eliot. Without her example, the great works of Henry James, Virginia Woolf, and Marcel Proust would scarcely have been possible. Through her, the English novel became not merely a mirror of society, but a profound exploration of the human soul.

As we turn next to the Brontë sisters, we encounter another fierce chorus of Victorian voices—more passionate, more defiant, yet driven by the same moral intensity. The Scroll of the Victorian novel unfolds further.

The Brontë Sisters — Passion, Isolation, and the Gothic Spirit

If George Eliot deepened the moral vision of the Victorian novel, the Brontë sisters exploded its emotional range.

In the windswept wilds of Yorkshire, far from the polite drawing rooms of London and the ordered landscapes of middle-class fiction, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë created novels that dared to voice the forbidden, the untamed, the sublimely defiant. Their works stand at the intersection of Romanticism and Victorian realism, infused with the Gothic spirit yet grounded in an acute awareness of psychological truth and social injustice.

It is one of the most astonishing facts of literary history that these three women—reared in an isolated parsonage on the edge of the Yorkshire moors, daughters of an impoverished Irish clergyman, largely self-educated—should have produced, in the span of a few short years, some of the most enduring masterpieces of the English novel.

Their fiction is fierce because their lives were fierce.

Loss, confinement, illness, and the stifling conventions of Victorian gender roles marked their brief, brilliant creative period. Their mother dead, their two elder sisters lost to tuberculosis, their only brother an alcoholic wreck, their own lives narrowed by poverty and isolation, the Brontës wrote not out of literary ambition but out of a need to give voice to their passions, their rebellions, and their vision of female strength.

They wrote against the grain of their time.

The polite novels of contemporary England offered moral uplift and socially acceptable heroines. The Brontës gave the world Jane Eyre, Heathcliff, Catherine Earnshaw, Helen Huntingdon—figures of wild emotion, uncompromising will, and moral courage in a world that sought to tame them.

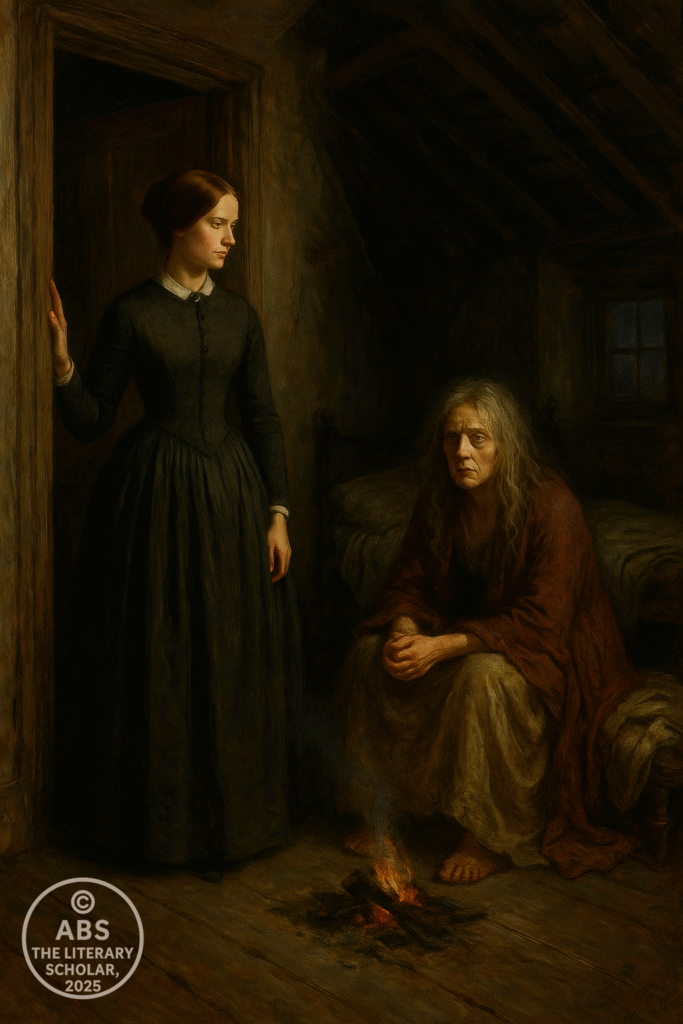

Charlotte Brontë — The Fire of Conscience

Of the three sisters, Charlotte Brontë achieved the greatest fame in her lifetime. Her Jane Eyre (1847) is one of the defining novels of the Victorian period—a tale of female selfhood, moral resilience, and the longing for love without subjugation.

Jane Eyre is remarkable for its psychological intensity and its uncompromising assertion of female dignity. In a society that viewed women as passive ornaments or domestic angels, Jane declares:

“I am no bird; and no net ensnares me: I am a free human being with an independent will.”

Charlotte drew upon her own experiences as a governess, a marginal figure in Victorian society, to portray Jane’s struggle for self-respect and agency. The novel’s Gothic elements—the mysterious Thornfield Hall, the madwoman in the attic, the Byronic figure of Rochester—serve not merely for sensational effect, but as metaphors for psychic and social repression.

Jane’s victory is not merely romantic but moral: she refuses to become Rochester’s mistress, chooses exile over compromise, and returns only on terms of equality and integrity. In an era of rigid gender hierarchies, Jane Eyre’s voice rang with revolutionary force.

Charlotte’s other novels—Shirley, Villette, The Professor—explore similar themes of female autonomy, emotional repression, and the search for authentic connection. Villette, in particular, is a masterpiece of interior narrative, portraying the loneliness and resilience of Lucy Snowe with a depth of psychological realism that anticipates modernist fiction.

Emily Brontë — The Wildness of Passion

If Charlotte was the fire of conscience, Emily Brontë was the voice of untamable passion. Her sole novel, Wuthering Heights (1847), stands alone in Victorian literature—a work of elemental intensity, narrative daring, and moral ambiguity.

At its heart is the relationship between Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw—a bond of love so fierce it defies life, death, and social convention. Catherine’s famous cry expresses the novel’s metaphysical vision:

“I am Heathcliff! He’s always, always in my mind—not as a pleasure… but as my own being.”

Wuthering Heights is a novel of anti-domesticity, where love is not a civilizing force but a wild, destructive power. The moors, with their savage beauty, mirror the characters’ inner turbulence. The novel’s narrative structure—a story within a story, told by unreliable narrators—adds layers of distance and ambiguity, challenging the reader to confront the moral darkness and psychic violence of its world.

Emily’s genius lies in her refusal to moralize or sentimentalize. Wuthering Heights is not a tale of redemption but a vision of passion beyond social or moral bounds. In doing so, it speaks to the Gothic unconscious of the Victorian age—a realm of repressed desires and forbidden emotions.

That a clergyman’s daughter, isolated on the Yorkshire moors, could create such a work of mythic power and narrative innovation is one of the enduring mysteries of literary history.

Anne Brontë — The Voice of Realist Rebellion

Anne Brontë, long overshadowed by her sisters, is today recognized as a major novelist in her own right. Her second novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848), is one of the boldest works of Victorian fiction—a fearless portrayal of marital cruelty, female resistance, and moral hypocrisy.

Through her heroine, Helen Huntingdon, Anne exposed the realities of alcoholic abuse, emotional coercion, and the legal powerlessness of women within Victorian marriage. Helen’s decision to flee her husband and support herself as an artist was nothing less than scandalous in its time.

Anne’s narrative rejects both Gothic excess and romantic idealism. Her realism is clear-eyed and unsparing; her moral vision is grounded in Christian integrity and radical empathy. The novel’s impact was so unsettling that Charlotte, after Anne’s death, sought to suppress its republication—a testament to its disruptive force.

Anne’s earlier novel, Agnes Grey, also deserves recognition for its portrayal of the exploitative world of governessing—a realm of emotional isolation and social contempt.

The Brontë Myth and the Afterlife

The Brontë sisters’ collective achievement is inseparable from their myth—the image of the three isolated geniuses creating masterpieces in a bleak parsonage, their lives shadowed by tragedy and early death. Yet behind the myth lies a more profound truth: they forged, out of personal suffering and moral courage, a body of fiction that forever altered the possibilities of the English novel.

Their works brought into Victorian literature a new psychological candor, a new willingness to confront forbidden emotions and social taboos. They expanded the novel’s range of female experience, voiced a defiant vision of personal integrity and spiritual longing, and infused English fiction with a Gothic power that still haunts its pages.

Without the Brontës, the Victorian novel would be a lesser thing—tamer, narrower, more complacent.

Their legacy endures because they dared to ask:

What happens when passion refuses to bow to convention?

What becomes of the soul when society seeks to cage it?

How can a woman claim her full humanity in a world designed to deny it?

These questions remain as urgent today as they were in 1847.

As we turn next to William Makepeace Thackeray, we encounter a very different Victorian vision—a satirist of social pretension, whose laughter cuts as sharply as the Brontës’ passion burns. The Scroll continues.

William Makepeace Thackeray — Satirist of Social Pretension

If Dickens was the moral conscience of Victorian fiction, and the Brontës its fierce emotional heart, William Makepeace Thackeray was its satirical intelligence—a writer who pierced the grand hypocrisies of Victorian society with a quill as sharp as a surgeon’s scalpel.

In a literary age often prone to moralizing, Thackeray reminded his readers—with wry, unflinching clarity—that virtue and vice wear the same respectable garments, and that ambition, vanity, and self-interest rule more lives than we care to admit.

Born in 1811 to a prosperous Anglo-Indian family, Thackeray came to manhood in the shadow of personal loss and financial instability. His father died when William was young; a large inheritance was squandered; his own family life was marred by tragedy—his wife’s descent into mental illness cast a long shadow over his domestic world. Like many of his characters, Thackeray knew well the gap between appearance and reality, between the glitter of public life and the melancholy of private truth.

He began as a journalist and illustrator, honing his satirical voice through essays, parodies, and sketches. But it was with the publication of Vanity Fair (1847–48) that Thackeray claimed his place as one of the great Victorian novelists. In this sprawling, unsparing work, he unveiled the moral bankruptcy of England’s upper and middle classes—a world where reputation matters more than character, and where success is often bought at the price of integrity.

A Novel Without a Hero

Vanity Fair bears the subtitle “A Novel Without a Hero”, and for good reason. Its central figures—Becky Sharp, the impoverished, brilliant adventuress; Amelia Sedley, the virtuous but passive ingénue; George Osborne, the callow aristocrat; Dobbin, the long-suffering paragon of loyalty—move through a world where self-interest reigns and where genuine moral goodness is rare and often unrewarded.

At the heart of the novel is Becky Sharp, one of the most unforgettable creations in English fiction. A woman of keen intelligence and unscrupulous ambition, Becky uses her wit, charm, and ruthless self-possession to rise in a society that would otherwise discard her. She is both villain and victim—a product of a world where a poor, clever woman has few honorable avenues to power.

Through Becky, Thackeray posed uncomfortable questions about the moral double standards of gender and class. In a society that idolized domestic womanhood and punished female ambition, Becky’s refusal to submit to her “proper place” is both scandalous and fascinating.

Yet Thackeray does not romanticize her. His genius lies in his cool, ironic detachment: he allows readers to admire Becky’s cleverness while recoiling from her manipulations. His moral vision is subtle, refusing the easy comforts of sentimentality or moral absolutism.

The Satirist’s Eye

Thackeray’s narrative voice is among the most distinctive in Victorian fiction—world-weary, ironic, often breaking the fourth wall to remind us that we are watching a puppet show staged by human vanity. He delights in exposing the absurdities of social pretension, the fickleness of public opinion, the hollow pomp of aristocratic life.

Consider his portrait of London society at its most gaudy:

“It is all Vanity Fair. The women are playing for husbands, the men for money. What more? Society is a game and its prizes are cards.”

Such sentences strip away the Victorian veneer of propriety, revealing a world governed not by Christian charity but by the law of the marketplace. Thackeray’s London is a vast bazaar of social climbing, where appearances matter more than virtue, and where the powerless are devoured by the powerful.

Yet Thackeray is never merely bitter. Beneath his satire lies a deep melancholy awareness of human frailty. His voice often shifts from mockery to gentle pathos, reminding us that behind every public mask is a vulnerable heart.

The Comedy of Realism

In contrast to Dickens’s flamboyant caricatures or the Brontës’ Gothic intensity, Thackeray cultivated a style of comic realism—a mode that sees life in all its absurdity, pettiness, and occasional nobility.

His characters are not larger-than-life heroes or villains, but flawed human beings, trapped in the mesh of societal expectations and personal weakness. Even his most admirable figures—such as the loyal Dobbin—are rendered with an acute awareness of their limitations.

This commitment to moral complexity makes Thackeray’s fiction feel strikingly modern. He was one of the first Victorian novelists to reject the neat moral resolutions of earlier fiction, insisting instead on the ambiguous, often disappointing nature of real life.

As he writes in Vanity Fair:

“Ah! Vanitas Vanitatum! Which of us is happy in this world? Which of us has his desire? or, having it, is satisfied?”

Such a vision resonates with the existential undercurrents that would later define modernist fiction. In this sense, Thackeray was both of his time and ahead of it.

Legacy Beyond Vanity Fair

Though Vanity Fair remains his masterpiece, Thackeray produced other notable works. Pendennis (1848–50) offers a semi-autobiographical account of a young man’s education and moral development, while The History of Henry Esmond (1852) experiments with historical fiction, blending 17th-century realism with psychological depth.

Yet across his oeuvre, Thackeray’s central preoccupation remains consistent: the comedy and tragedy of human vanity. He invites us to laugh at the follies of society, but also to recognize them in ourselves.

The Laugh That Cuts

Why does Thackeray still matter?

Because in an age saturated with social performance, public image, and moral pretense, his satire cuts as sharply today as it did in 1848. His novels remind us that virtue is rare, ambition is blind, and happiness is fragile—and that the only proper response to this human comedy is a mixture of irony, compassion, and humility.

He gave the Victorian novel a new register—one that could accommodate both moral insight and comic skepticism. Without Thackeray, the tradition of realist satire in English fiction—from Forster to Waugh to Ishiguro—would be immeasurably poorer.

As we turn next to the wider field of Victorian fiction, we shall encounter other voices—less famous perhaps, but no less vital. The Scroll widens, and with it, our understanding of the many ways in which the Victorian novel sought to illuminate the age.

Other Significant Novelists of the Victorian Era

While Dickens, Eliot, the Brontës, and Thackeray stand as the towering figures of Victorian fiction, they did not write alone.

Across the long arc of the nineteenth century, a diverse chorus of novelists enriched the English literary landscape—each bringing new themes, new forms, and new social perspectives to the evolving art of the novel.

To understand the full vitality of Victorian fiction, we must attend to these other voices: writers who expanded the scope of the novel to include industrial conflict, women’s rights, political life, sensational thrills, and even philosophical inquiry.

It is through their works that we glimpse the astonishing breadth of Victorian imaginative life—a literature restless, searching, and always responsive to the changing currents of its time.

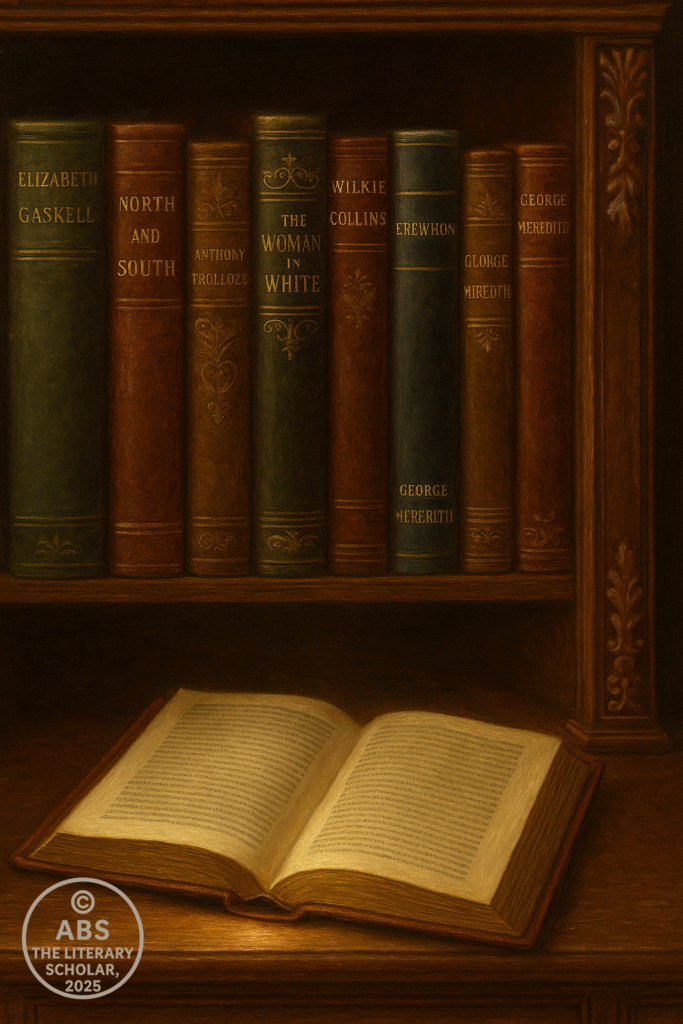

Elizabeth Gaskell — The Social Conscience of the Industrial Novel

Among the most important of these writers is Elizabeth Gaskell (1810–1865), whose novels brought the experiences of working-class England into the heart of middle-class literary consciousness.

A Unitarian minister’s wife in Manchester, Gaskell was uniquely positioned to observe the human costs of industrialization—the poverty, disease, and class antagonism that transformed northern cities into centers of both economic power and social misery.

Her first major novel, Mary Barton (1848), shocked polite readers with its unsparing depiction of factory life and its frank portrayal of working-class anger. In a period when Chartist agitation and labor unrest were feared by the elite, Gaskell’s sympathetic treatment of her working-class characters was a bold moral stance.

But her masterpiece is North and South (1855), a novel that dramatizes the clash between industrial capitalism and traditional values through the story of Margaret Hale, a young woman from the rural south who relocates to the industrial north. Through Margaret’s evolving understanding of both the mill owners and the workers, Gaskell explores themes of social responsibility, mutual respect, and the possibility of ethical capitalism.

Gaskell’s fiction is remarkable for its balance of realism and moral vision. She does not idealize the poor, nor demonize the rich; rather, she insists on the human dignity of all her characters. In this, she extended the novel’s role as an agent of social empathy and reform.

Anthony Trollope — The Chronicler of Social Institutions

Where Gaskell explored the world of industrial England, Anthony Trollope (1815–1882) became the great chronicler of English institutions—the Church, Parliament, the landed gentry, and the professional classes.

His vast oeuvre—over 40 novels—is most celebrated for two great series: The Barsetshire Chronicles and The Palliser Novels.

The Barsetshire Chronicles (1855–67), beginning with The Warden and culminating in The Last Chronicle of Barset, offer a richly textured portrait of provincial life centered on the fictional county of Barsetshire. Through a network of interwoven characters—clergymen, doctors, gentry, merchants—Trollope examines the tensions between tradition and progress, duty and self-interest, public expectation and private desire.

The Palliser Novels (1864–80), by contrast, explore the world of British politics through the career of Plantagenet Palliser and his brilliant wife Lady Glencora. These novels combine political realism with personal drama, offering insight into the machinery of Victorian power and the personal costs of public life.

Trollope’s prose lacks the stylistic flair of Dickens or the psychological depth of Eliot, but his great strength lies in his steady moral intelligence and his keen eye for the complex workings of society. He remains a master of social comedy, characterization, and narrative continuity.

Wilkie Collins — The Father of the Sensation Novel

Victorian fiction was not all earnest realism; it also delighted in thrills, mysteries, and psychological suspense. No writer contributed more to this dimension than Wilkie Collins (1824–1889), whose The Woman in White (1859) helped launch the sensation novel—a genre blending domestic settings with crime, deception, and gothic atmosphere.

The Woman in White, with its multiple narrators, secret identities, and twists of fate, captivated readers and demonstrated the novel’s potential to explore the darker undercurrents of Victorian life. Collins followed this success with The Moonstone (1868), widely regarded as the first modern detective novel—introducing elements of investigation, suspense, and psychological complexity that would influence later crime fiction.

Collins’s sensation novels often exposed the legal and social vulnerabilities of women, critiquing marriage laws, inheritance practices, and the abuses of patriarchal authority. In this, his work aligned with the broader progressive currents of Victorian literature, even as it provided gripping entertainment.

Bulwer-Lytton, George Meredith, Samuel Butler — Voices at the Margins

Other Victorian novelists, though less central today, made important contributions to the era’s literary diversity.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803–1873), though now best known for the phrase “It was a dark and stormy night,” was a prolific writer of historical romance, science fiction, and social satire. His novel The Last Days of Pompeii (1834) exemplifies the Victorian taste for exotic historical settings and moral spectacle.

George Meredith (1828–1909), a novelist of intellectual subtlety and stylistic experimentation, anticipated many of the concerns of modernist fiction. Works such as The Egoist (1879) explore gender dynamics, self-consciousness, and the ironies of social performance with remarkable sophistication.

Samuel Butler (1835–1902), in Erewhon (1872) and The Way of All Flesh (published posthumously in 1903), offered philosophical satire and psychological insight that challenged Victorian complacency. His critique of religious hypocrisy and family tyranny anticipated many of the rebellious currents of twentieth-century thought.

A Chorus of Voices

Taken together, these writers demonstrate that the Victorian novel was not a monolithic tradition, but a dynamic and evolving form—capable of encompassing industrial strife, political satire, domestic realism, sensational intrigue, and philosophical reflection.

Their works expanded the moral scope and formal possibilities of fiction, helping to prepare the ground for the even more daring experiments of the late Victorian and modernist periods.

As we close this survey of Victorian fiction, we see an age not only of great novels, but of great diversity—a literary landscape alive with competing visions, moral debates, and aesthetic innovations.

The novel had become, in the Victorian era, a moral mirror of society—and, in the hands of its finest practitioners, a means of shaping that society’s conscience.

The poet had sung; the novelist had spoken. And still, the Victorian Scroll unfolds.

As the Victorian century advanced, the novel became its most trusted mirror—reflecting not merely the surface of society, but the depths of its moral life.

Through the voices of Dickens, Eliot, the Brontë sisters, Thackeray, and the many other writers we have surveyed, the English novel matured into a form capable of encompassing the full complexity and contradiction of an age torn between progress and tradition, faith and doubt, justice and complacency.

This was not a literature of easy consolations. Its heroes were often flawed; its endings were rarely triumphant. Yet the Victorian novel’s greatness lies precisely in its refusal to simplify the human condition. It asked its readers to see themselves in its pages—not as idealized figures, but as beings shaped by weakness, desire, kindness, and moral struggle.

Through its characters and its stories, the novel taught Victorian England to imagine the lives of others—to cultivate the sympathies that George Eliot so wisely called the foundation of moral life. In an age of empire and industry, where human suffering too easily became an abstraction, the novel insisted that every life mattered, that behind every statistic stood a face, a story, a soul.

As we close this second part of our Scroll, we recognize that the Victorian novel accomplished something rare in literary history: it became the conscience of its age—a vehicle through which an entire society reflected upon its values, its failings, and its highest aspirations.

Yet the Victorian imagination did not rest content with realism and moral instruction.

In the decades that followed, new voices would emerge—poets and aesthetes, rebels and visionaries—who would challenge the very foundations of Victorian thought. The lyrical, the sensual, the mystical, and the decadent would rise to contest the moral earnestness of the age.

From the solid ground of the novel, the Scroll now turns once more toward the airier realms of poetry and art—toward those voices who, in the twilight of the Victorian world, sought to capture beauty for its own sake, and to find meaning where reason faltered.

With the close of this Part, we have traced the great moral journey of Victorian fiction—a literature born from conscience, sustained by imagination, and marked by the inexhaustible variety of human life.

As we prepare to enter the next phase of this journey, let us carry forward the insight the Victorian novel leaves us: that art, in its finest moments, teaches us not only how to read, but how to live.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance