From the Last Glow of Beauty to the First Shadows of Modern Doubt

From The Professor's Desk

As the long Victorian century neared its close, the tone of its poetry grew more muted, its certainties more fragile. This was the realm of Late Victorian Poets and the Aesthetic Turn—a moment when verse turned inward, away from moral pronouncements and toward the pursuit of beauty for its own sake.

The great moral and lyrical energies of early and mid-Victorian verse had stirred the age’s conscience. The novel mirrored the complexities of its social world. Yet by the final decades of the century, both art and imagination drifted toward twilight realms—toward an aesthetic that prized beauty itself, or sought to distill from a fading culture its last lingering hues.

Already, in our earlier Scroll, we traced the work of the Pre-Raphaelite poets—Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Morris, Christina Rossetti—who had planted the seeds of an artistic rebellion: a poetry that celebrated sensual beauty, symbolic richness, and emotional depth over public duty.

Now, in the final Victorian years, this aesthetic impulse would grow more daring, more decadent, even defiant. Algernon Charles Swinburne would sing of pagan delights and spiritual revolt; Oscar Wilde would embody the creed of art for art’s sake; Walter Pater would teach that life itself must be lived as an art. And in a darker register, poets like Thomas Hardy and Gerard Manley Hopkins would voice the era’s spiritual anxieties and tragic pessimism, their lines haunted by a world where old beliefs no longer sufficed.

The Victorian Scroll moves now toward its final music—a music not of triumph, but of twilight. Through these poets, we hear an age contemplating its own limits, longing for beauty even as it senses the impermanence of all things. The sun of empire still shone outward, but inwardly, the Victorian mind was preparing to enter the modernist night.

The Aesthetic Twilight — From Pre-Raphaelites to Decadence

As we have seen earlier in our Scroll, the Pre-Raphaelite poets had already begun to transform Victorian verse—shifting it from public moralism toward a private world of beauty, symbol, and spiritual yearning. In the works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Christina Rossetti, and William Morris, we glimpsed a poetry rich with sensual imagery and aesthetic rebellion—a verse that sought not to preach, but to enchant.

Now, in the final decades of the Victorian era, that aesthetic impulse grew more daring—no longer content merely to revive medieval imagery or celebrate idealized love. The poets of the Aesthetic Twilight embraced art for art’s sake, the beauty of the transitory, and even the thrill of the forbidden. Their verses shimmered with pagan defiance, erotic suggestion, and symbolic complexity—a response, perhaps, to a culture where old faiths were failing, and where beauty itself seemed the last absolute.

Swinburne — The Song of Defiance

At the vanguard of this movement stood Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837–1909)—a figure as notorious as he was brilliant. Where earlier Victorian poets had wrestled with faith or celebrated moral order, Swinburne exulted in the sensual, the pagan, and the rebellious.

His Poems and Ballads (1866), published to scandal and acclaim, broke decisively with Victorian decorum. Here were poems that reveled in erotic longing, that invoked classical deities and pre-Christian rites, that sang of spiritual revolt with a hypnotic musicality unmatched by his peers.

“Thou hast conquered, O pale Galilean; the world has grown grey from thy breath.”

(Hymn to Proserpine)

In this haunting line, Swinburne mourns the triumph of Christian asceticism over the joyous sensuality of the pagan world—a theme that recurs throughout his work. For Swinburne, the body and the senses were not sources of sin but of ecstatic experience; his poetry celebrated a world of fleeting beauty rather than one of enduring moral certainties.

His metrical innovations and lush musicality left a profound mark on late Victorian and early modernist verse. Oscar Wilde, among others, learned from Swinburne the art of making language itself a spell—a tissue of sound and rhythm capable of entrancing the reader beyond meaning.

Yet Swinburne’s verse also speaks to a deeper cultural anxiety. Beneath its defiant tone lies a recognition that the old spiritual order has collapsed—and that art alone may not suffice to replace it. His poetry offers beauty without comfort, desire without redemption—a fitting anthem for an age in twilight.

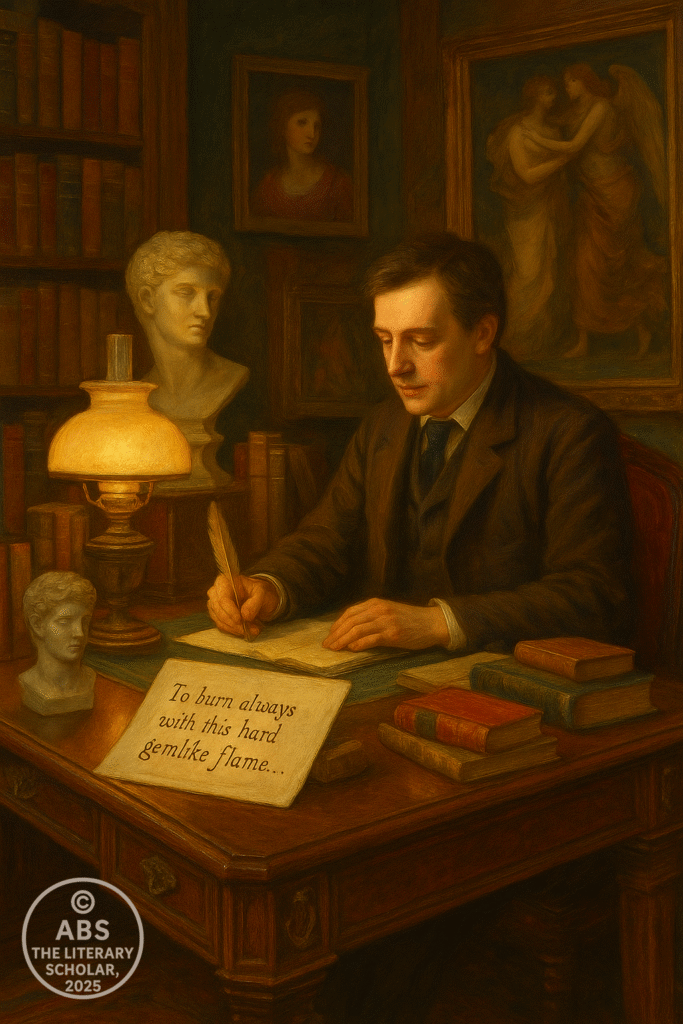

Walter Pater — Life as Art

Where Swinburne sang, Walter Pater (1839–1894) whispered. A critic and essayist rather than a poet, Pater became the high priest of Aestheticism, giving the movement its most eloquent credo.

In The Renaissance (1873), Pater articulated the aesthetic ideal: that life should be lived with the utmost intensity, that we must seek out those experiences—artistic, emotional, intellectual—that make us most fully alive.

“To burn always with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life.”

Such sentences transformed the ambitions of a generation of young artists and writers. For Pater and his disciples, the highest good was not moral righteousness or social utility, but the cultivation of exquisite moments—an existence shaped by artistic perception and sensual refinement.

This philosophy was both liberating and perilous. On one hand, it challenged the Victorian cult of duty, encouraging a more personal and authentic relationship with beauty. On the other, it risked a drift into decadence, narcissism, and ethical indifference.

Pater’s influence extended far beyond his own circle. Without him, the works of Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, and the later Symbolists would scarcely be conceivable.

Oscar Wilde — The Tragic Star of Aestheticism

At the heart of the Aesthetic movement stood its most dazzling and ultimately tragic figure: Oscar Wilde (1854–1900). No Victorian writer embodied more fully the tensions of the age—between wit and wisdom, beauty and corruption, celebrity and ostracism.

In both his life and his art, Wilde sought to live Pater’s creed. His plays—The Importance of Being Earnest, Lady Windermere’s Fan, An Ideal Husband—are masterpieces of social satire, their dialogue crackling with epigrams that still resonate:

“The only way to get rid of temptation is to yield to it.”

“I can resist everything except temptation.”

Yet beneath the surface brilliance lies a profound commentary on the hypocrisies of Victorian morality—a world where appearances masked desires, and where the pursuit of beauty was often punished by a society obsessed with propriety.

Wilde’s only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), is the quintessential text of Aesthetic Decadence. In the story of Dorian, who remains outwardly youthful while his hidden portrait bears the marks of his corruption, Wilde offers a parable of art’s seductive power and its moral dangers.

“Behind every exquisite thing that existed, there was something tragic.”

Wilde’s own life would embody this truth. His trial and imprisonment for “gross indecency” shattered his public career and left him a broken man. Yet his writings continue to challenge us: Can art stand apart from morality? Can beauty justify itself? What price must we pay for the pursuit of pleasure?

The Aesthetic Contradiction

The poets and aesthetes of the late Victorian twilight bequeathed us a body of work of extraordinary sensual richness and intellectual provocation. They taught that art need not be a servant of morality or social duty; that it could be self-justifying, a realm of pleasure, mystery, and emotional truth.

Yet they also revealed the limits of such a vision. In a world increasingly aware of its spiritual vacuum, art alone could not fully console. The Aesthetic movement’s brightest stars—Swinburne, Pater, Wilde—offered beauty without faith, style without substance. Their verses shimmer, but they do not always heal.

As the Victorian century waned, a new poetic voice would emerge—one marked by deeper spiritual struggle and tragic vision.

In the works of Gerard Manley Hopkins and Thomas Hardy, we shall hear this next movement of the Scroll: a poetry of ecstasy and despair, of grief and endurance, sounding in the fading light of an age soon to pass.

Gerard Manley Hopkins — The Ecstasy of Spiritual Struggle

As the Victorian era edged toward its twilight, a new kind of poetic voice emerged—a voice unlike any that had preceded it.

It did not sing of sensual delight alone, like the aesthetes. Nor did it seek refuge in the nostalgia of lost faith, like the cultural critics. Instead, it gave expression to the deepest contradictions of the age: faith pursued in a world of doubt, ecstasy wrested from despair, beauty glimpsed in the heart of struggle.

That voice was Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889)—a poet whose works were unknown in his own lifetime, but who would come to be recognized as one of the most original, profound, and influential figures in the evolution of modern poetry.

A Life of Inner Conflict

Hopkins was born into a cultured Anglican family and educated at Oxford, where he came under the spell of the great religious thinker John Henry Newman. In 1866, to the dismay of his family, he converted to Roman Catholicism—a decision that would shape both his spiritual journey and his poetic voice.

In 1868, Hopkins entered the Jesuit order, embracing a life of ascetic discipline and spiritual rigor. For years, he ceased writing poetry altogether, believing that his vocation demanded the sacrifice of personal ambition. Yet the poetic impulse never wholly died; when his Jesuit superior asked him to compose a poem commemorating a shipwreck, Hopkins returned to verse with renewed fervor.

Thus began one of the most extraordinary late blooms in literary history. Between 1875 and his death in 1889, Hopkins composed poems of such linguistic innovation and spiritual intensity that they would not be fully appreciated until well into the twentieth century.

Sprung Rhythm and the New Poetic Music

One of Hopkins’s great contributions to poetry was his invention of sprung rhythm—a metrical system that broke from the regular iambic patterns of traditional English verse. In sprung rhythm, the number of stressed syllables remains constant, while the number of unstressed syllables varies—creating a verse that mimics the natural rhythms of speech and evokes an almost musical intensity.

Consider the opening of The Windhover, perhaps Hopkins’s most famous poem:

“I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon…”

The line leaps and surges, its stresses mirroring the swoop and dive of the falcon it describes. Hopkins’s language here is not merely descriptive; it is incantatory, designed to embody the very movement it evokes.

Through such innovations, Hopkins expanded the expressive range of English poetry, anticipating the experiments of modernist poets like T. S. Eliot and Dylan Thomas.

Nature as Sacramental Vision

Yet Hopkins’s formal genius was inextricable from his spiritual vision. For him, the world was a sacrament—a visible manifestation of divine presence. He developed the concept of “inscape”: the unique inner essence of each created thing, reflecting God’s creative energy.

This vision is radiant in poems like Pied Beauty, a hymn of praise to the variegated beauty of the natural world:

“Glory be to God for dappled things—

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow…”

Here, Hopkins celebrates the imperfection and diversity of creation—not as flaws, but as expressions of divine creativity. In an era haunted by Darwinian materialism and the erosion of religious certainty, Hopkins’s poetry insists on the enduring mystery and wonder of the world.

Yet this vision was hard-won. Hopkins was a man of profound spiritual struggle. His Jesuit duties often left him exhausted and isolated. His sense of unworthiness and spiritual dryness deepened in his final years, as he served in industrial Liverpool and Dublin, far from the intellectual circles that had once nourished him.

The Terrible Sonnets — A Dark Night of the Soul

The poetry of Hopkins’s later years—the so-called Terrible Sonnets—offers a harrowing record of spiritual desolation. In poems like Carrion Comfort and No Worst, There is None, we hear a voice grappling with despair, self-loathing, and the apparent silence of God.

“O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed.”

(No Worst, There is None)

Here, the poet’s inner world becomes a precipice of dread. Gone is the confident celebrant of nature’s glory; in his place stands a soul wracked by doubt, clinging to faith through sheer will.

Yet even in these bleakest poems, Hopkins’s language retains its incantatory power—a testament to the poet’s unbroken commitment to truthful expression, even when hope falters.

Legacy and Influence

Hopkins died in relative obscurity in 1889, his poems unpublished save for a few circulated among friends. It was only in 1918, when his friend Robert Bridges published his collected poems, that the literary world awakened to his genius.

Today, Hopkins is recognized as a precursor of modernism, a poet who bridged the Victorian and modern sensibilities. His innovations in rhythm, daring syntax, and spiritual depth have influenced countless poets, from Eliot to Seamus Heaney.

But beyond technical legacy, Hopkins’s poetry speaks to the enduring human struggle to find meaning, beauty, and divine presence in a world of uncertainty. In his greatest lines, we hear the cry of a soul that will not surrender to despair, that seeks grace even in grief, and that dares to praise amid the darkness.

**As the Victorian Scroll nears its close, we shall now turn to one final voice—Thomas Hardy, whose poetry embodies the tragic vision of a century ending in doubt, yet rich with the hard-won wisdom of endurance.

Thomas Hardy and the Poetry of Tragic Pessimism

As the nineteenth century entered its final twilight, few poetic voices captured the age’s underlying mood of doubt and fatalism more profoundly than Thomas Hardy.

Known in his lifetime primarily as a novelist, Hardy would, after the controversies surrounding his fiction, devote himself increasingly to poetry—creating a body of verse that stands today as one of the great legacies of late Victorian and early modern English literature.

In Hardy’s poetry, the late Victorian mind confronted the truths its earlier optimism had tried to evade: the indifference of the universe, the fragility of human hope, and the slow erosion of all certainties once grounded in religion, tradition, or empire.

Where Swinburne and Wilde had sought to console the age with aesthetic beauty, and Hopkins had wrestled toward an anguished but stubborn faith, Hardy’s voice emerged as tragic, stoic, and unsparingly honest—offering not the comfort of redemption, but the dignity of clear-eyed endurance.

A Novelist’s Journey Toward Poetry

Born in 1840 in the rural county of Dorset, Hardy was steeped from childhood in the rhythms of country life—its seasonal rituals, oral traditions, and deep sense of historical continuity. Yet he was also a product of the Victorian age, acutely aware of the forces of modernization, scientific skepticism, and social change that were unsettling the old rural world.

Hardy rose to fame as a novelist in the 1870s and 1880s, with works such as Far from the Madding Crowd, The Mayor of Casterbridge, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, and Jude the Obscure. These novels depicted the human struggle against social constraints, personal desire, and blind chance—themes that would later find their most distilled expression in his poetry.

After the critical storm surrounding Jude the Obscure (1895)—condemned for its sexual frankness and bleak vision—Hardy largely abandoned fiction. From the late 1890s until his death in 1928, he poured his creative energies into poetry, producing over 900 poems and establishing himself as one of the most important poetic voices of the age.

The Fatalistic Vision

At the heart of Hardy’s poetry lies a fatalistic worldview. Influenced by Darwinian thought, Victorian agnosticism, and his own philosophical temperament, Hardy saw the universe not as the creation of a benevolent deity, but as an impersonal and indifferent mechanism.

“The Immanent Will that stirs and urges everything,” he writes in Hap, does so without regard for human happiness or suffering. In the absence of divine purpose, Hardy’s poetry insists, life must be faced with honest awareness, not illusion.

Consider the bleak joy of Hap, one of his early philosophical poems:

“If but some vengeful god would call to me

From up the sky, and laugh: ‘Thou suffering thing,

Know that thy sorrow is my ecstasy…’”

Here, Hardy almost longs for a malevolent deity, for at least such a god would render human suffering meaningful. But no such god exists. The universe is deaf to human cries; its workings are governed by blind chance, not moral design.

Yet Hardy is not a nihilist. His poetry confronts this cosmic indifference with a tone of stoic endurance and compassion for human frailty. In this, he gives voice to one of the defining attitudes of the late Victorian and early modern age.

Elegy for a Vanishing World

Hardy’s verse is also a sustained elegy for the vanishing rural England of his youth. In poems such as The Darkling Thrush (1900), he mourns the passing of an older, more rooted way of life:

“I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-grey,

And Winter’s dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.”

The poem’s landscape is one of decay and desolation, a metaphor for the moral and cultural exhaustion Hardy perceived in fin-de-siècle England. Yet even here, a sudden burst of the thrush’s song reminds the poet—and us—that unexpected moments of beauty and vitality persist, however fragile.

This is Hardy’s great poetic gift: to evoke both the harsh truths of existence and the fleeting, poignant moments that give life its bittersweet richness.

War, Fate, and Historical Irony

Hardy’s historical consciousness is another key dimension of his poetry. Deeply aware of the ironies of fate and the cyclical patterns of history, he often portrays human endeavors as tragically outmatched by larger, impersonal forces.

In The Convergence of the Twain (1915), written after the sinking of the Titanic, Hardy juxtaposes the ship’s luxurious pride with the unseen shaping forces of destiny:

“And as the smart ship grew

In stature, grace, and hue,

In shadowy silent distance grew the iceberg too.”

Here, human ambition meets cosmic indifference, and history unfolds with an irony no mortal can foresee.

Similarly, in Channel Firing, written on the eve of World War I, Hardy imagines the dead rising from their graves, alarmed by the sound of naval gunnery exercises—only to be reassured by God that war is an eternal, unchanging human folly:

“‘It will be warmer when

I blow the trumpet (if indeed I ever do);

For you are men,

And rest eternal sorely need.’”

Such poems reveal Hardy’s profound skepticism regarding human progress. For him, history does not advance toward moral enlightenment; it merely repeats its ancient cycles of violence and loss.

Compassion Without Consolation

Yet Hardy’s pessimism is never cold. His poetry is infused with a deep compassion for individual suffering—for the broken hopes, lost loves, and quiet resilience of ordinary lives.

In Drummer Hodge, he memorializes a young English soldier buried far from home during the Boer War:

“Yet portion of that unknown plain

Will Hodge for ever be;

His homely Northern breast and brain

Grow to some Southern tree.”

There is no grand consolation here—only the simple dignity of remembrance, the merging of human frailty with the eternal processes of nature.

Hardy’s compassion extends especially to women and the marginalized—those crushed by social convention or tragic circumstance. His portrayals of lost love and emotional regret resonate across his verse, lending it a haunting personal poignancy.

Legacy and Influence

Thomas Hardy stands at the threshold of modernism—his verse bridging the Victorian moral imagination and the existential questioning of the twentieth century.

His influence on poets such as W. H. Auden, Philip Larkin, and Seamus Heaney is profound. In an age that no longer trusts in divine providence or historical progress, Hardy’s poetry offers an ethic of honest recognition and enduring compassion.

In one of his most famous lines, Hardy captures the tragic vision that defines his art:

“If way to the better there be, it exacts a full look at the worst.”

This, perhaps, is the final wisdom of Hardy’s poetry—and of the Victorian Scroll itself. As an age of empire, faith, and certainty drew to its close, Hardy taught his readers that truth must be faced without illusion, and that even in the shadow of loss, the human spirit endures.

The Waning Victorian Spirit — Cultural Pessimism and the Death of an Age

As the sun set on the nineteenth century, the vast edifice of the Victorian world stood seemingly at its zenith—yet within its foundations, cracks had begun to widen.

The British Empire spanned continents; industry and commerce thrived; Queen Victoria, an aged matriarch, presided over a realm on which the sun never set. Yet behind the glitter of imperial triumph, the Victorian mind grew increasingly shadowed by cultural fatigue, spiritual doubt, and the haunting sense that the moral certainties of the age were eroding.

The poets of this final phase—Arnold, Hardy, Hopkins, and others—did not sing songs of conquest or progress. Their verses became elegies, laments, and stoic meditations on a world whose outward strength could no longer disguise its inner uncertainties.

The Mutiny Of 1857— A Shock to the Imperial Conscience

One of the first deep tremors beneath the imperial façade was the Indian Mutiny of 1857—or, as Indian historians rightly call it, the First War of Independence.

This violent uprising shook the British imagination to its core. The notion of benevolent empire was abruptly confronted by the realities of colonial oppression, cultural arrogance, and violent resistance. For many Victorians, the Mutiny triggered a crisis of confidence: if even the “jewel in the crown” of the Empire could burn with rebellion, how stable was this imperial order?

The British response was brutal; the Raj was established with firmer control. Yet in the cultural psyche, something had shifted. The Mutiny exposed the deep moral contradictions of the imperial project, contradictions that would darken the tone of much late Victorian thought.

In the poetry of this period, one finds little imperial triumphalism. Rather, there is an undertone of unease, an awareness that beneath the rhetoric of progress lay forces the Empire could not fully master.

The Late Victorian Political Scene — Triumph and Anxiety

The latter decades of Victoria’s reign saw Britain at the height of its global power—and at the height of its imperial anxieties. The so-called Scramble for Africa, the extension of British rule into vast new territories, and the maintenance of dominion over India gave the outward impression of an unstoppable empire.

Yet the realities were more complex. The costs of empire were mounting; nationalist movements simmered across the colonies; the Irish Question remained unresolved. Domestically, the old class structures were under strain; scientific materialism and Darwinian thought eroded religious faith; the urban poor remained trapped in cycles of deprivation.

It is no accident that the greatest poetry of this late phase rarely celebrated empire. Instead, it became increasingly personal, philosophical, and melancholic—concerned with individual loss, spiritual uncertainty, and the passing of time.

Matthew Arnold — The Cultural Critic’s Lament

Among the most prophetic voices of this twilight was Matthew Arnold. Already in Dover Beach (written c. 1851), he had perceived the ebbing of religious faith:

“The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar…”

Here is not the voice of Victorian confidence, but of existential melancholy—a recognition that the moral and spiritual cohesion of the past could no longer be sustained.

Arnold’s later prose writings—Culture and Anarchy, Literature and Dogma—continued this lament. He diagnosed a society increasingly dominated by Philistinism—the pursuit of material wealth without spiritual depth. For Arnold, the role of culture and poetry became all the more vital: to preserve human values in an age of mechanization and spiritual impoverishment.

Poetry as Elegy — The Final Mood of the Age

As the Victorian era drew to its close, its poetry became a literature of elegy. The tone was no longer heroic or confident, but reflective, nostalgic, even resigned.

Hardy, in particular, became the great poet of this mood. In The Darkling Thrush, composed as the nineteenth century ended, he captured the spirit of an age conscious of its own twilight:

“And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited.”

The thrush’s unexpected song offers not redemption, but a poignant contrast to the poet’s own weariness—a final image of beauty against the backdrop of cultural decline.

The Death of Queen Victoria — The Symbolic End

When Queen Victoria died in 1901, after a reign of nearly 64 years, the symbolic weight of her passing was immense. She had been the figurehead of an entire moral and cultural world—a world of duty, discipline, empire, and faith.

With her death, the Victorian age itself seemed to pass into history. The new century would soon be marked by war, social upheaval, and artistic revolution—forces the Victorians could scarcely have imagined.

In poetry, the tone had already foretold this transition. The final decades of the Victorian Scroll had been marked not by triumph, but by melancholy wisdom—the recognition that certainty was gone, that beauty and meaning must now be sought with greater humility and deeper honesty.

Toward Modernism

The poets who followed—Yeats, Eliot, Pound, and others—would build upon this legacy of spiritual questioning and aesthetic innovation. But it was the late Victorian poets—Arnold, Hopkins, Hardy—who had already prepared the ground, who had dared to voice the elegiac mood of an age ending.

Their poetry remains a testament to the enduring human need to seek meaning amid impermanence, to find beauty amid disillusion, and to speak with integrity even when the old songs of faith have faded.

The Victorian era began with hymns to progress and ended with elegies for certainty.

Across the long arc of the nineteenth century, its poets gave voice to the shifting moods of an age that had imagined itself secure beneath the twin pillars of faith and empire—only to find, by its close, that both had grown fragile.

From the early splendor of Tennyson’s heroic verse to the fierce passion of the Brontës, from the Pre-Raphaelite celebration of beauty to the dark songs of Swinburne and the tragic wisdom of Hardy, Victorian poetry unfolded like a vast tapestry, rich with changing hues—at times radiant, at times shadowed, always alive to the deeper currents of its civilization.

In these final decades, as we have traced, the poets turned increasingly to the inner life: to the moral ambiguities, spiritual doubts, and existential questions that the outward triumphs of empire could no longer conceal. In the lines of Arnold, Hopkins, and Hardy, we hear not lament alone, but a new kind of courage—the courage to face impermanence, to find beauty in ephemeral things, to speak truth even when the old certainties have gone silent.

When Queen Victoria died in 1901, an era passed with her. The Scroll of the Victorian poets closes here—not with the bright trumpet of empire, but with the quieter, more enduring music of those who have learned to sing in the twilight.

Yet poetry itself did not end. From the elegies of the late Victorians would arise the modernist imagination—an art more restless, more fragmented, but still driven by the same ancient longing to make meaning from the mysteries of human experience.

Thus we close the Victorian Scroll—with gratitude to its poets for their songs of light and shadow, of glory and grief, of hope and hard-won wisdom. The page turns now toward the modern age—but the voices of the Victorians, rich and resonant, will echo through every line that follows.

With the close of this final Scroll, we have witnessed the full arc of Victorian poetry: from its moral grandeur to its aesthetic twilight, from imperial confidence to existential humility.

As the modern era beckons, we carry forward not only the forms of Victorian verse, but its deepest lesson: that in every age, poetry must confront the truths of its time—and dare, still, to sing.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance