By The Literary Scholar

(Who firmly believes that if Beckett had written “Friends,” they’d still be waiting for coffee.)

Let’s begin by stating the obvious: the Theatre of the Absurd is not your average evening at the theatre. There are no heroes, no villains, no gripping love triangles, and certainly no satisfying climaxes. In fact, a typical absurdist play has all the forward momentum of a shopping cart with a stuck wheel—wobbling in circles, occasionally crashing into despair, and somehow managing to make you laugh in the process. This is not theatre where things happen. This is theatre where the lack of happening becomes the entire point. And that, strangely enough, is the magic of it.

Born out of the philosophical rubble after World War II, the Theatre of the Absurd didn’t emerge with flowers and forgiveness—it arrived with a shrug and an existential crisis. The world had witnessed the collapse of meaning, and playwrights like Samuel Beckett, Eugène Ionesco, Jean Genet, and Harold Pinter decided they wouldn’t write plays that pretended otherwise. Gone were the neat moral arcs and coherent resolutions. In came plays where characters didn’t know why they were there, what they wanted, or if they even existed in the first place. It was as if theatre collectively stood up, looked the audience in the eye, and asked:

“What makes you think life has a plot?”

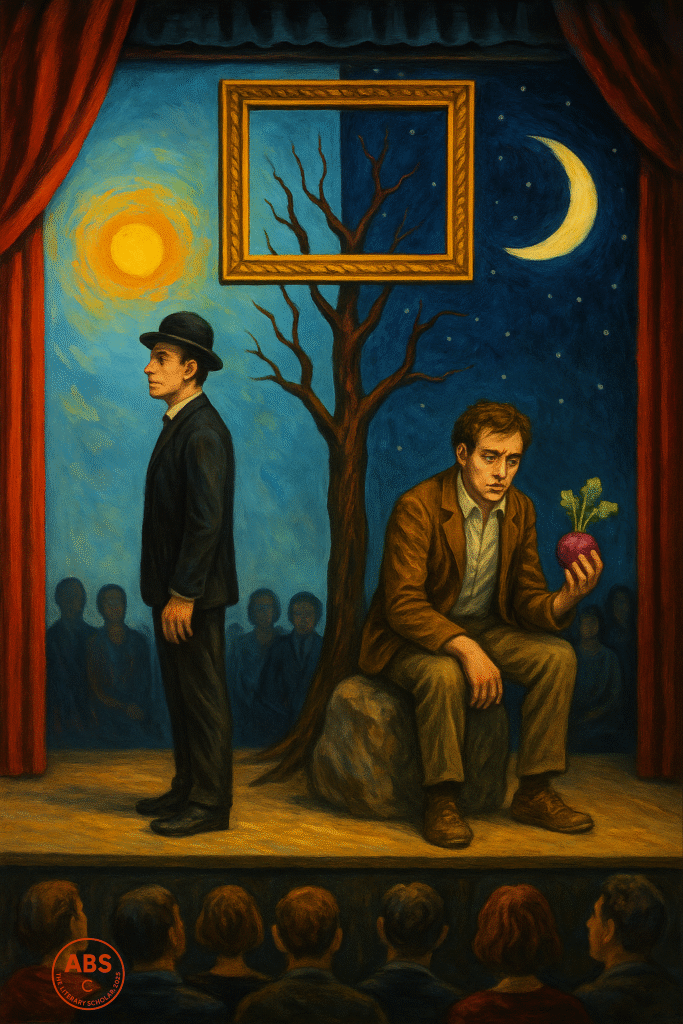

Take Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, the uncontested crown jewel of absurdism. Two men, Vladimir and Estragon, stand under a tree waiting for someone named Godot. They wait. They eat carrots. They take off boots. They contemplate suicide. They wait some more. Spoiler: Godot never arrives. Some audience members have spent entire performances wondering if Godot is a metaphor for God, salvation, purpose—or just the pizza delivery guy who never came. Regardless, what unfolds is the most compelling two hours of elegant nothingness you’ll ever sit through. One can imagine pitching this play to a modern streaming platform:

“So, the two main characters just… wait?”

“Yes.”

“And what’s the climax?”

“They continue to wait.”

“Any explosions?”

“Only internal.”

And therein lies the genius. Beckett understood something most of us drown in caffeine and content to avoid: that life, for the most part, is a series of waiting rooms. Waiting for meaning, for love, for emails to be answered, for purpose to call us back. And just like Estragon and Vladimir, we fill the void with banter, distractions, and occasionally, talking about our boots.

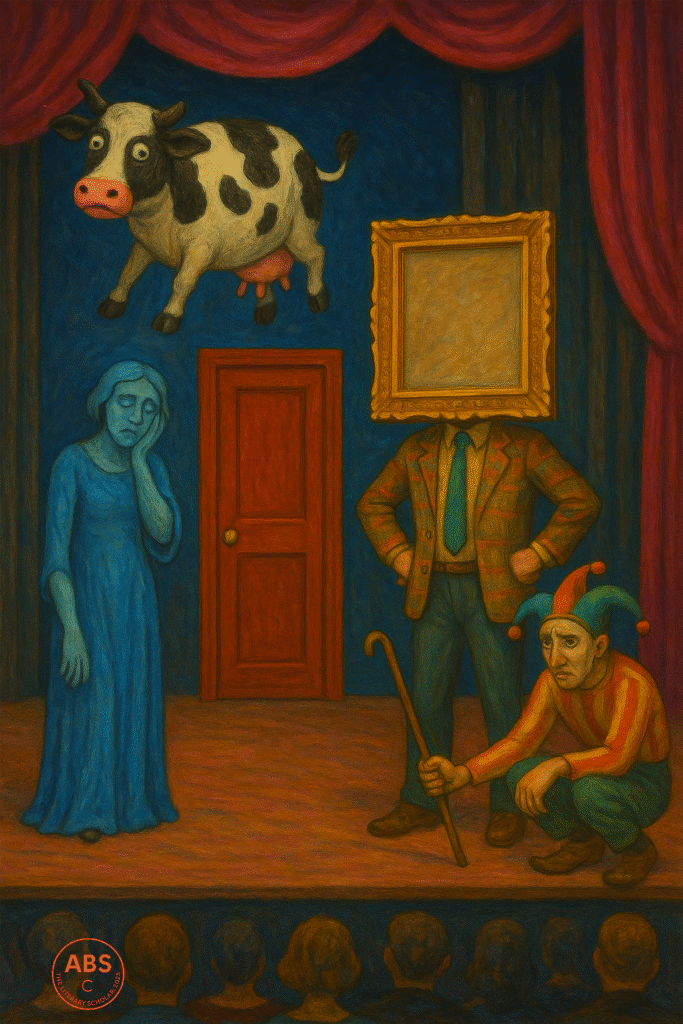

If Beckett was the philosopher-poet of the absurd, Ionesco was the chaotic prankster. His play The Bald Soprano begins innocently enough—two couples chatting in a middle-class British living room—but quickly descends into linguistic lunacy. Characters spout clichés, repeat themselves, talk in nonsense, and eventually abandon any illusion of logic or coherence. Dialogue turns into pure sound, meaning melts faster than an ice cream on a July footpath. It’s like attending a dinner party where everyone speaks fluent gibberish and no one notices.

“She’s kept a kitchen-maid for seventeen years. She always wears blue.”

“That’s odd, so does the maid at the Watsons’.”

It’s also remarkably relatable. Ever sat through a family WhatsApp group conversation lately? Auntie asks about the weather, cousin replies with a meme, uncle shares unsolicited political insight, and someone inevitably posts “Good morning” with dancing sunflowers at 3 a.m. The Bald Soprano was simply ahead of its time. Ionesco would’ve thrived in meme culture.

What these playwrights realized—long before we did—is that modern life isn’t just absurd, it’s absurd in high-definition. We live in a world where language is constantly used to say nothing, where we schedule meetings to decide if we need meetings, where we ghost people digitally and call it “closure.”

“Nothing to be done.” — Estragon, every Monday morning, spiritually

Enter Harold Pinter, the master of the pause. In his plays like The Dumb Waiter or The Birthday Party, characters don’t just speak—they hover. Silence becomes dialogue. A pause becomes a punchline. A character asking “What?” followed by silence becomes a full existential exchange. Pinter understood that what’s not said often weighs heavier than what is—and that, my dear reader, is very much how awkward elevator rides work.

But the brilliance of absurdism isn’t limited to how it portrays disconnection. It’s also in how it strips theatre down to its bones. These plays are minimal: a tree, a chair, a platform, maybe a rope. There’s no glittering spectacle, no grand sets or costume changes. It’s just raw, unfiltered human vulnerability under a spotlight. Where classical theatre gives us kings and quests, the absurd gives us two men staring into a void, asking, “Are you sure we’re even here?”

While classical plays entertain, absurdist plays disturb, then force a slow smirk. They don’t pat you on the back; they nudge you off the ledge and ask what you think of the view.

And what’s most remarkable is how these plays transform despair into comedy. You laugh—not because it’s funny in the traditional sense, but because there’s nothing else to do. It’s the same kind of laughter you produce when you realize you’ve been on hold for customer service for 47 minutes, and the hold music just looped for the fifth time. It’s the laughter of someone who’s figured out the punchline was never coming. Or perhaps, the joke was you all along.

“We are all born mad. Some remain so.” — Lucky, from Waiting for Godot

(Also seen last week on Twitter with a frog emoji.)

And though the movement emerged in the 1950s, it never really left. In fact, it’s quietly running the show in our modern world. Our social media feeds are digital absurdist plays: endless scrolling, empty conversations, curated personalities performing for an invisible audience, all while we wait for “likes” as proof of existence. A tweet that reads, “Existence is pain lol” followed by a photo of someone’s perfectly plated avocado toast—that’s Beckett with a filter.

Contemporary shows like BoJack Horseman, Russian Doll, Fleabag, The Good Place—all sip from the Absurdist fountain, blending wit with ontological anxiety, laughter with longing.

Because in the end, absurdism doesn’t claim to solve the crisis of meaning. It doesn’t offer a grand theory, or an escape hatch. It simply acknowledges the mess. It tells us, with a raised eyebrow and impeccable timing: yes, life is fragmented, awkward, repetitive, strange—and somehow, beautifully so.

It invites us not to despair, but to find the comedy in the chaos, the poetry in the pauses, and the humanity in the nonsense.

So no, the Theatre of the Absurd may not give you heroes or happy endings. But it will give you the strange comfort of knowing that your existential confusion has excellent company—and dialogue.

And who knows?

Maybe Godot is still on his way.

He’s just… stuck in traffic.

They peeled meaning from silence, staged nonsense with precision, and turned waiting into metaphor. Between pauses and punchlines, they dared to ask: “Is anyone listening?”

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Scholar

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance