From Godot’s Delays to Rhinoceros Rampages—Why Drama Finally Snapped

ABS The Literary Scholar Believes:

That when history becomes incoherent and coffee loses meaning, theatre must step in—not to explain, but to mirror the madness back with impeccable comic timing.

Welcome to the Play Where Nothing Happens—and That’s the Point

Let’s begin with a confession: this scroll contains no protagonist, no climax, and absolutely no moral resolution. There will be no catharsis, no grand orchestral fadeout, and you’ll likely leave more confused than you arrived. But that, dear reader, is the joy of Theatre of the Absurd—a genre that looked at tragedy, comedy, and plot structure and said, “What if… we just didn’t?”

Once upon a mid-20th century time, humanity hit a philosophical speed bump—also known as two world wars, the Holocaust, the atom bomb, and the growing realization that God might’ve left the chat. Thinkers like Sartre and Camus began suggesting that life had no inherent meaning, and the theatre folks went, “Splendid! Let’s write a play where people talk nonsense under a tree for two hours.”

Thus emerged a strange and wonderful artistic rebellion: a drama of disorientation, a comedy of dread, a tragedy with giggles. It wasn’t entertainment as much as a shared existential crisis in three acts.

The dialogue became elliptical. Time looped. Chairs were set for invisible guests. Characters waited endlessly for mysterious saviors. And audiences sat frozen between laughter and despair, muttering, “Was that the intermission or the end?”

This is the world of Beckett, Ionesco, Pinter, Genet—men who handed us scripts that made no sense, only to reveal we were already living them.

So pull up a chair (an imaginary one will do), shrug off your desire for closure, and welcome absurdity like an old friend who never learned to knock.

The play has begun. The meaning has exited stage left.

And we?

We’re still waiting for Godot.

PART 1: Before Absurdity—The Calm Before the Breakdown

Keyphrase: Origins of Theatre of the Absurd

Focus Keywords Integrated: absurd drama, absurd play, absurd playwrights, absurd theater, absurd drama in English literature, absurd play definition

“When reality stops making sense, it’s theatre’s turn to go rogue.”

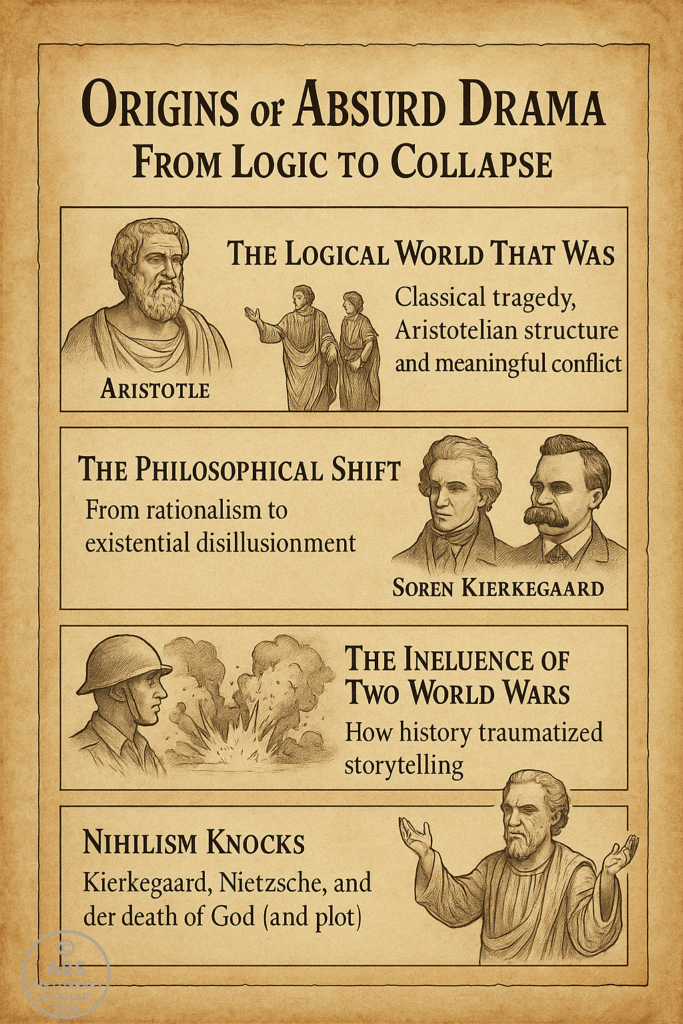

The Logical World That Was: When Drama Behaved Itself

The Logical World That Was: When Drama Behaved Itself

Once upon a time, drama followed rules. Plot had a beginning, middle, and end. Characters had motivations. Dialogue had direction. And plays—believe it or not—had meaning. The classical Greek dramatists handed us neat blueprints: Aristotle’s Poetics said that tragedy should invoke pity and fear, protagonists should suffer a fall from grace, and deus ex machina should only drop in occasionally—not every five lines.

Even Shakespeare, the unruly bard of poetic chaos, gave us structured dramatic arcs. His heroes bled, but they bled on schedule. Hamlet may have stalled, but eventually, even he delivered. The Enlightenment took this further—plays were moral lessons with powdered wigs. The Victorian stage polished the formula till it gleamed with emotional order. Tragedy meant tears. Comedy meant marriage. And nobody turned into a rhinoceros mid-script.

This era was the opposite of absurd drama—it was organized, cohesive, and emotionally satisfying. You entered the theatre expecting something to happen. And by curtain call, it usually had.

Ah, innocence.

The Philosophical Shift: When Certainty Packed Its Bags

The Philosophical Shift: When Certainty Packed Its Bags

The world didn’t fall apart overnight—but it did start doubting itself with increasing flair. The comfortable cushion of rationalism began to sag. Thinkers like Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and later Heidegger tiptoed into consciousness, whispering inconvenient questions: What if life had no purpose? What if truth was subjective? What if we’re all just pretending we know what we’re doing?

Cue existentialism, the stylish intellectual midlife crisis that insisted humans were alone in an uncaring universe with no divine helpline. If existence was absurd, then perhaps our entire social script—love, work, ethics, even theatre—was one elaborate farce.

This set the perfect philosophical foundation for absurd drama in English literature. If life has no clear plot, why should a play?

Camus would later describe the absurd condition as the confrontation between a rational mind and an irrational world. He didn’t mean absurd like “funny ha-ha” but absurd like “screaming internally while smiling at the postman.”

And the stage was listening.

The Influence of Two World Wars: Humanity Forgets Its Lines

The Influence of Two World Wars: Humanity Forgets Its Lines

If modern philosophy gently nudged logic off its pedestal, the World Wars body-slammed it into rubble. The sheer scale of destruction, genocide, and mechanized death made traditional drama feel… dishonest. How could a neat five-act structure explain Auschwitz? How could noble monologues capture Hiroshima?

Theatre responded not with realism, but with rebellion.

Absurd playwrights like Samuel Beckett and Eugène Ionesco saw the polished traditions of European theatre and thought, Why are we still pretending this makes sense? If reality now meant bureaucracy, bombs, and bodies, then drama had to reflect the absurd theater the world had become.

In absurd plays, the stage became a metaphor for the postwar psyche: empty, repetitive, directionless. Waiting became a plot. Speaking became pointless. Chairs were set for people who never came. Dialogue was circular. Meaning? Optional.

This wasn’t nihilism for the sake of coolness—it was art imitating breakdown. Audiences were no longer seeking comfort—they wanted to see their confusion reflected, with just enough tragicomic detachment to not run screaming into the lobby.

Nihilism Knocks: Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and the Murder of Meaning

Nihilism Knocks: Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and the Murder of Meaning

We must thank—or blame—philosophy once again. Kierkegaard asked, What does it mean to exist as an individual in a meaningless cosmos? (Answer: nothing comforting.) Nietzsche declared God was dead, and with Him, went moral absolutes, universal truths, and well-behaved protagonists. Suddenly, the tragic flaw wasn’t pride—it was being alive and conscious in a void.

This wasn’t just background noise for playwrights. It was the music score.

Absurd drama, at its core, is theatre that rejects traditional structure, logical dialogue, and character motivation—because it sees all those things as lies we tell ourselves. In place of reason, we get ritual. In place of action, we get waiting. In place of meaning, we get a character who shouts gibberish into the abyss—and the abyss claps.

When someone asks, “What is the definition of absurd play?” the answer isn’t in a glossary. It’s in a moment: a man under a tree waiting for someone who never comes. A woman buried up to her waist, putting on lipstick while civilization collapses behind her. A couple who can’t remember why they’re in the room, or what their names are, or whether they’re even in a play.

These aren’t accidents. These are the hallmarks of absurd drama. They’re the legacy of a century that broke faith in logic, progress, and tidy endings.

Curtain Call for Coherence

Curtain Call for Coherence

And thus, the stage was set—literally—for the Theatre of the Absurd to emerge.

It didn’t crash in with fanfare. It seeped into the wings like a leak in the plumbing of Western drama. Bit by bit, absurd playwrights dismantled the rituals of old theatre. The hero was replaced with a tramp. The plot was replaced with silence. The climax was replaced with… another pause.

To understand absurd theater, you have to unlearn your desire for resolution. You have to let go of what drama was supposed to do—and let it be instead.

It’s not just a form of theatre. It’s a diagnosis.

A diagnosis of a world where Godot never comes, chairs are set for invisible guests, and the most profound line in the play is the sound of someone not speaking.

Welcome to absurd drama.

Welcome to the breakdown.

PART 2: Enter Existentialism (Stage Left, Confused)

Keyphrase: Existentialism and Absurd Theatre

“Life is meaningless. But tickets are non-refundable.”

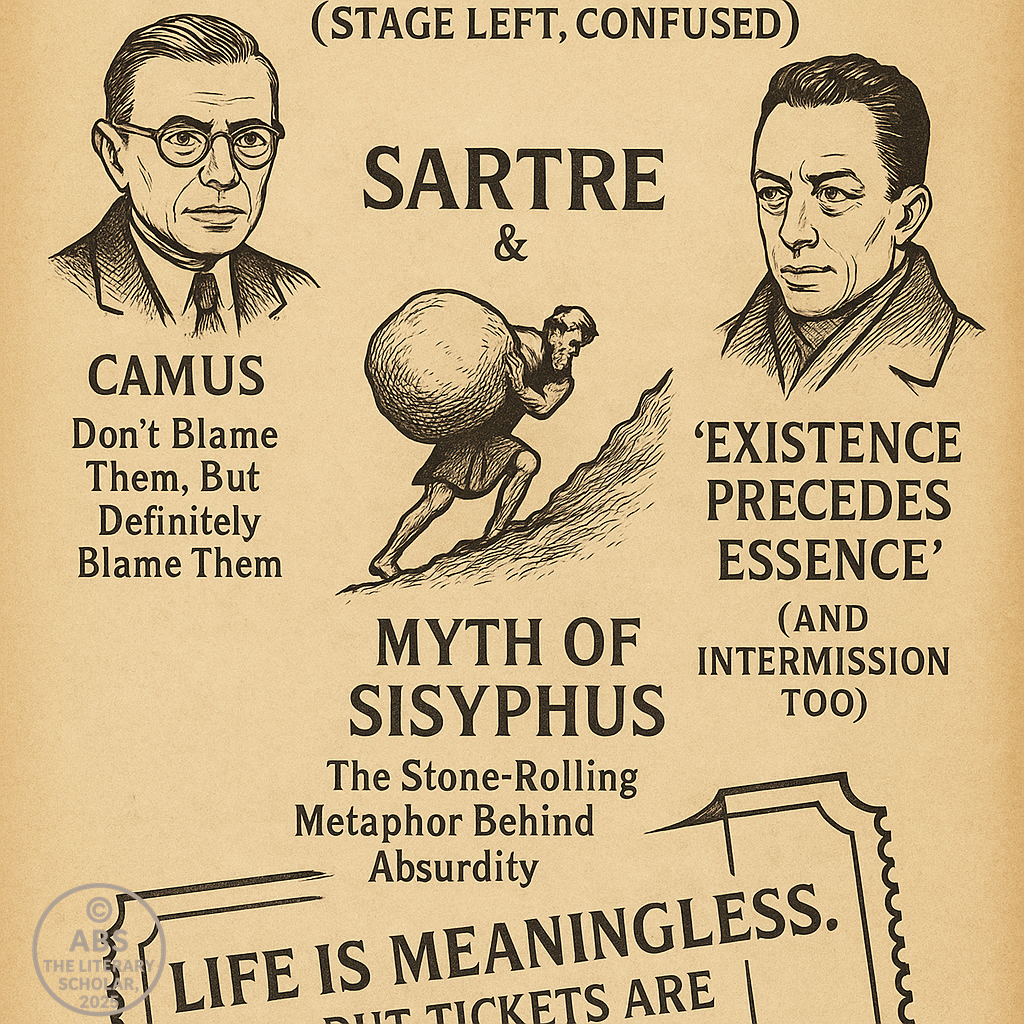

Sartre & Camus: Don’t Blame Them, But Definitely Blame Them

Sartre & Camus: Don’t Blame Them, But Definitely Blame Them

If absurd drama were a tragicomic guest list, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus would be seated near the hors d’oeuvres—grumbling about the wine and insisting that the party doesn’t matter, but staying anyway.

Sartre never called his work “absurd theatre,” and Camus most certainly did not write plays with rhinoceroses in them. And yet, without these existentialist philosophers, we wouldn’t have the philosophical bedrock on which the entire absurd drama movement clumsily pirouetted.

Sartre’s most famous soundbite—“existence precedes essence”—was less of a theatre cue and more of a philosophical mic drop. It means humans are not born with a divine purpose, just a blank script and the pressure to improvise. If you mess it up, too bad—there’s no director to shout “Cut!”

In No Exit, Sartre delivered one of the earliest absurd plays of the modern era. Three people trapped in a room forever? No sleeping, no eyelids, no mirrors, just each other? It wasn’t called absurd drama, but it was already halfway there. He even gave us that immortal line: “Hell is other people.” (Though the theatre lobby can come close.)

Camus, on the other hand, wasn’t a playwright by instinct, but he was the man who handed absurd drama its core metaphor: Sisyphus.

The Myth of Sisyphus: Rolling with Absurdity

The Myth of Sisyphus: Rolling with Absurdity

Let’s talk rocks.

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus retells the ancient Greek story of a man cursed by the gods to roll a boulder up a hill for eternity—only for it to tumble back down each time. No victory. No applause. No point. Just endless repetition. (Cue Beckett’s agent perking up.)

Camus argues this is the perfect metaphor for modern existence. Life is repetitive, meaningless, and laborious, and yet—we must imagine Sisyphus happy. Not because the task changes, but because our awareness of the absurd makes us free.

Absurd theatre springs straight out of this philosophical pit. What is Waiting for Godot if not Sisyphus in bowler hats, waiting instead of rolling? What are Ionesco’s lectures in The Lesson if not the absurd repetition of education turned violent? What are Pinter’s pauses but the silence between rocks tumbling?

Absurd plays don’t just reflect life’s meaninglessness—they embrace it, polish it, and hand it back to you with a wink and a shrug.

Existence Precedes Essence (And Intermission)

Existence Precedes Essence (And Intermission)

Existentialism isn’t here to comfort you. It’s here to cancel the GPS and hand you a compass with no needle. And from this philosophical chaos, absurd drama finds its rhythm—or lack thereof.

Let’s translate:

“Existence precedes essence” = You are not born with a role—you choose it, poorly, often while mumbling under a tree.

This line, meant to liberate, also terrifies. If there’s no divine blueprint, no narrative arc, then life is not a plot—it’s a loop.

This is exactly what we see in absurd theatre:

Dialogue that goes nowhere.

Characters unsure of their identity.

Settings that feel like purgatory with lighting.

Repetition that mocks memory and motivation.

Take Beckett’s “Krapp’s Last Tape”: a man listening to old recordings of himself. Nostalgia becomes absurd as identity fractures. Or Ionesco’s “The Bald Soprano”: where small talk loops into nonsense like a dinner party cursed by Google Translate.

Every absurd play is a living enactment of existential paralysis—you exist, but do you know who you are, or why you’re in Act Two?

Theatre, once a moral compass or mirror to society, is now a hall of cracked mirrors, and existentialism handed over the hammer.

From Existentialism to Absurd Drama: Cue the Applause (Or Don’t)

From Existentialism to Absurd Drama: Cue the Applause (Or Don’t)

Here’s the great paradox: existentialism is deeply serious, and absurd drama often looks ridiculous. But that’s precisely the point. The seriousness becomes unbearable—so theatre breaks it, subverts it, and makes it darkly funny.

This is why absurd playwrights aren’t just philosophers in costume. They’re jesters in a collapsing court, mocking our need for structure even as they give us a stage full of characters desperately trying to understand one another with words that fail.

This is also why absurd plays don’t offer answers. Instead, they give you silences, repetitions, chairs with no occupants, and characters asking questions they can’t remember five lines later.

They reflect the existential dread Sartre and Camus diagnosed—but do so through theatrical mockery, awkward pauses, and scenes that refuse to end.

So, yes—don’t blame Sartre and Camus.

But also, absolutely blame them.

They gave us the philosophy.

Beckett, Ionesco, and Pinter turned it into absurd theatre.

And audiences never recovered.

PART 3: What Is Theatre of the Absurd Anyway?

Keyphrase: Characteristics of Theatre of the Absurd

“Theatre of the Absurd is what happens when plays start gaslighting the audience.”

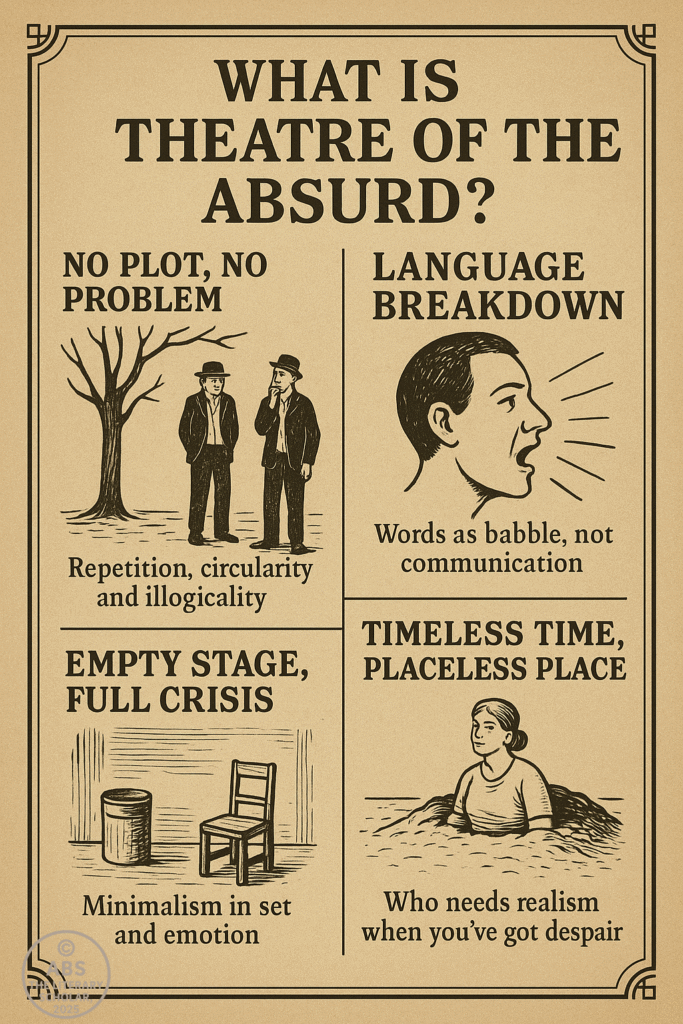

No Plot, No Problem

No Plot, No Problem

Imagine entering a theatre. The lights dim. A character steps on stage. You wait for action—conflict, rising tension, a climax. Instead, the character sits. Then stands. Then forgets why they stood. Then sits again. Someone else enters. They speak in disconnected fragments about their uncle’s mustache. Then they both wait for someone named Godot. Spoiler: He never shows up.

Welcome to absurd drama, where plot isn’t just missing—it’s been banned for trying too hard to make sense.

One of the defining characteristics of absurd theatre is its deliberate rejection of conventional narrative. Gone are the neatly wrapped three-act structures. In their place: circularity, repetition, and inertia.

Think of it like this: If traditional theatre is a road trip with a map, absurd plays are existential traffic jams—you’re honking in place while wondering if you were ever driving at all.

Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is often called the absurd play definition in action. It features two tramps who do nothing, say nothing of consequence, and wait for a man who never comes. And yet, it’s considered a masterpiece. Why? Because its refusal to “go anywhere” is the very point: it mirrors the audience’s silent scream, “Is this it?”

Language Breakdown: Babble as Philosophy

Language Breakdown: Babble as Philosophy

Words—once the noble tools of Shakespeare, Molière, and Oscar Wilde—become meaningless sound effects in absurd theatre.

In traditional plays, language reveals character, builds tension, delivers wisdom. In absurd drama, it loops, contradicts, collapses. It’s not communication. It’s linguistic jazz with broken instruments.

Take Eugène Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano. In this absurd play, dialogue escalates into nonsensical statements like:

“The soup is on the chair. The ceiling is under the carpet. Bobby likes buttered bread.”

The audience laughs, but uneasily. Are they hearing children babble or adults malfunction?

This language breakdown is central to the definition of absurd theatre. Words are used not to clarify but to expose how much we hide behind them. When people speak in absurd plays, they aren’t sharing—they’re performing the collapse of meaning.

It’s theatre where dialogue is the enemy of understanding.

Empty Stage, Full Crisis

Empty Stage, Full Crisis

The absurd stage is often… not much of a stage. A tree. A bench. A trash can. A woman buried in sand. A table with too many chairs. Welcome to absurd minimalism, where the set design has anxiety and the props have abandonment issues.

This lack of spectacle isn’t budget-related—it’s existential design. The stripped-down stage reflects the emotional and philosophical emptiness of the characters. You won’t find velvet curtains and chandeliers here. Instead, you’ll find space—wide, blank, and deafening.

This aesthetic makes the audience hyper-aware of the void. Every silence stretches. Every gesture feels magnified. The spotlight isn’t on the action—it’s on the absence of action.

In Endgame, Beckett gives us two characters in bins and one man who can’t sit. In The Chairs, Ionesco gives us dozens of invisible guests and two actual chairs. Nothing says “crisis of meaning” like an entire room full of no one.

So yes, absurd theatre is minimalist—but emotionally, it’s maximalist in existential dread.

Timeless Time, Placeless Place

Timeless Time, Placeless Place

Another classic feature of absurd theatre? It takes place nowhere, at no time, for no reason.

Settings are deliberately vague. Time is elastic, unmeasured. Days don’t pass. Characters don’t age. You’re in a non-place in a non-era, where the past doesn’t matter and the future is a rumour.

Why? Because absurd plays don’t care about context. They care about condition—the human condition. The setting is stripped of identity so the play can focus on something rawer: the existential confusion of simply being.

In Happy Days, Winnie is buried waist-deep in earth, applying lipstick and pretending everything is fine. We never know where she is or why she’s stuck. That’s the point. She’s every one of us, performing normalcy while life swallows us inch by inch.

This quality—the timelessness and placelessness—is what makes absurd drama feel both alien and strangely familiar. You’ve never been on Beckett’s stage, but you’ve been in his emotional weather.

What Is Theatre of the Absurd? A Definition with No Instructions

What Is Theatre of the Absurd? A Definition with No Instructions

So let’s answer the question everyone Googles:

“What is theatre of the absurd?”

“What is absurd play definition?”

It’s drama where:

Plot is irrelevant

Language is suspicious

Time is broken

Settings are abstract

Meaning is missing—and mourned

But it’s not meaningless. Rather, absurd theatre reflects the search for meaning in a world that keeps hiding it behind metaphor and furniture.

It doesn’t provide answers. It stages the question—again, and again, and again.

Final Act (No Curtain)

Final Act (No Curtain)

Theatre of the Absurd doesn’t ask you to understand it. It asks you to sit in discomfort, laugh when you shouldn’t, and maybe, just maybe, recognize your own quiet panic in the babble and silence of the characters.

Absurd playwrights didn’t write plays for applause. They wrote them because nothing else made sense anymore.

So yes, absurd plays are strange.

They defy genre.

They resist closure.

They end without ending.

But they’re honest in a way that few things are: they mirror the nonsense we pretend isn’t nonsense.

Theatre of the Absurd is not an escape.

It’s a magnified reflection of reality—stripped, stunned, and just slightly hysterical.

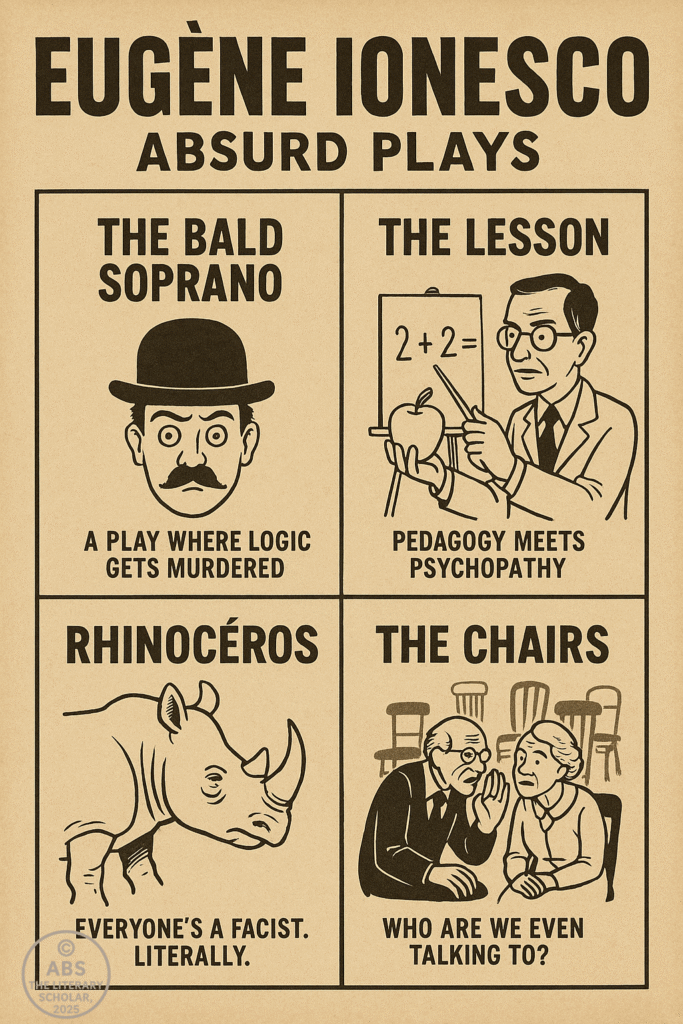

PART 4: Eugène Ionesco – The Bald Pioneer

Keyphrase: Eugène Ionesco absurd plays

“Ionesco: making furniture emotional and language illiterate since the ’50s.”

Welcome to the Ionesco Dimension: Where Chairs Talk and Syllogisms Attack

Welcome to the Ionesco Dimension: Where Chairs Talk and Syllogisms Attack

If Samuel Beckett was the bleak philosopher-poet of absurd theatre, then Eugène Ionesco was its deranged jester—armed with a monocle, a thesaurus, and a grudge against small talk.

Born in Romania, raised in France, and confused everywhere else, Ionesco didn’t set out to change modern theatre. He just wanted to learn English. Legend has it that while practicing with a language textbook, he noticed how phrases meant to teach conversation sounded like existential breakdowns.

“The ceiling is up. The floor is down. Bobby likes bread.”

“Why?” – said Ionesco. “Why does Bobby like bread? WHO IS BOBBY?”

Thus began a career in absurd drama where characters lose control of language, plot gets hit by a bus, and logic dissolves faster than soap in boiling water.

The Bald Soprano – When Small Talk Turns into War Crimes

The Bald Soprano – When Small Talk Turns into War Crimes

Let’s begin with the absurd play that started it all: The Bald Soprano. Spoiler alert: there is no soprano, and no one is bald.

This play is less a plot and more a linguistic landslide. A bourgeois couple begins a polite conversation. So does another. They don’t know each other. Then they do. Then they don’t again. A fireman arrives. Nothing catches fire.

The dialogue deteriorates into:

“The Pope lives in Rome. The Pope is bald. Dogs have four legs. Therefore, the Pope is a dog.”

This is not bad writing—this is absurd theatre at its finest. Ionesco shows how language, when detached from meaning, becomes menacing nonsense. And yet, it feels eerily familiar. Haven’t we all been to dinner parties that sound exactly like this?

By the end of The Bald Soprano, the characters devolve into pure gibberish. The audience sits, stunned, realizing they’ve been watching the murder of logic in real-time.

The Lesson – When Teaching Becomes Fatal

The Lesson – When Teaching Becomes Fatal

Next up in the Ionesco fever dream: The Lesson. It starts innocently enough: a professor welcomes a student. She wants to learn. He wants to teach. A simple, safe premise—until the professor begins speaking like he swallowed a dictionary and never learned to chew.

The absurdity escalates quickly. The professor grows aggressive, the pupil becomes confused, and lessons on subtraction morph into screams about totalitarianism.

The tension builds until—spoiler—he kills her. (With a knife. Because the syllabus didn’t already stab hard enough.)

The maid walks in. She sighs. She resets the room. A new pupil arrives.

Welcome to absurd drama’s version of academic tenure.

This play is a brutal satire of pedagogy, authority, and the illusion of understanding. It’s not just absurd. It’s dangerously relevant, especially if you’ve ever sat through a lecture and wondered who was losing their mind faster—you or the professor.

Rhinocéros – Everyone’s a Fascist. Literally.

Rhinocéros – Everyone’s a Fascist. Literally.

Rhinocéros is Ionesco’s masterpiece of absurd political allegory, in which the townspeople turn into rhinoceroses. Yes. Rhinoceroses. By the end of the play, almost everyone has grown horns, snorts, and stomps.

And no, this isn’t a children’s cartoon. It’s a savage critique of how totalitarian ideologies creep into normal lives—until people wake up one morning and find their neighbor chewing on shrubbery and justifying fascism.

The protagonist, Bérenger, watches it all happen in horror. His coworkers become rhinos. His friends stomp off into the jungle. His girlfriend grows a horn mid-sentence.

The real terror? No one minds.

This is the brilliance of absurd theatre—it uses the surreal to unmask the too-real. Rhinocéros isn’t about beasts. It’s about how easily people abandon reason, individuality, and humanity in the name of conformity.

And it’s funny. Which makes it worse.

The Chairs – Ghost Guests and Shouting into the Void

The Chairs – Ghost Guests and Shouting into the Void

In The Chairs, we meet an elderly couple preparing chairs for an audience. Someone important is going to speak. The guests begin arriving… except they’re all invisible.

As the couple addresses the empty chairs, they repeat anecdotes, declare truths, and grow increasingly frenzied. Then comes the Orator—the only visible “guest”—who finally arrives to deliver the message that will save the world.

And guess what? He’s mute.

He can’t speak.

He writes on a blackboard.

The message is gibberish.

Then the old couple jumps out the window. Curtain.

Welcome to absurd theatre, where the punchline is the punch. The meaning you were waiting for? It never arrives. And that’s the meaning.

The Absurd Playwright Who Gave Language a Midlife Crisis

The Absurd Playwright Who Gave Language a Midlife Crisis

Eugène Ionesco’s absurd plays are absurd not because they’re random, but because they are exact mirrors of how we live—awkwardly, repetitively, pretending to understand each other while muttering clichés and hoping no one notices we’re lost.

His work is proof that absurd drama isn’t about nonsense—it’s about making sense of how nonsensical life already is.

In the hands of this absurd playwright, chairs become symbols, language becomes weaponized confusion, and polite conversations unravel into primal roars.

Ionesco’s absurd theatre doesn’t explain the world.

It just walks on stage, points at it, and laughs—loudly, awkwardly, and beautifully.

PART 5: Samuel Beckett – Waiting for the End of Meaning

Keyphrase: Samuel Beckett Theatre of the Absurd

“Beckett: Where characters wait, speak nonsense, and die. And it’s profound.”

Waiting for Godot – Two Men, One Tree, Zero Plot

Waiting for Godot – Two Men, One Tree, Zero Plot

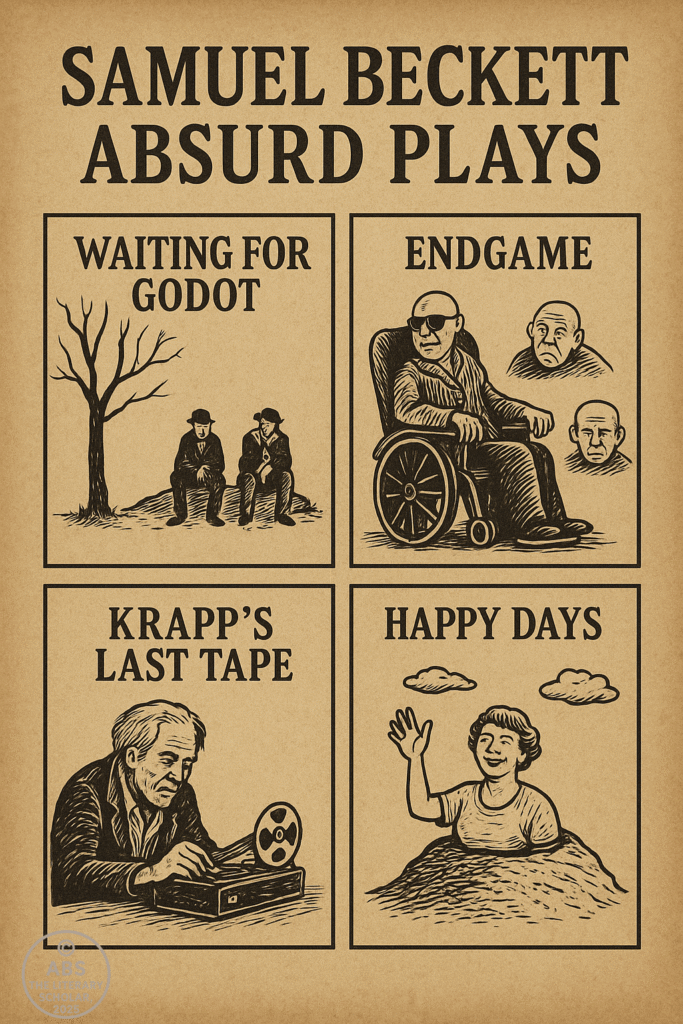

We begin with the most famous absurd play ever written—and perhaps the only one that became a cultural idiom. Waiting for Godot is not just Samuel Beckett’s absurd theatre masterpiece—it is the absurd play that redefined drama itself.

Here’s the setup: Two men, Vladimir and Estragon, stand near a tree. They wait. They talk. They leave. They come back. They wait again. A third man (Pozzo) enters, dragging another (Lucky) on a rope. Lucky monologues incoherently about God, time, and dance. Everyone forgets what they were doing. Godot never comes. Curtain.

What’s it about?

Precisely.

The genius of this absurd drama is that nothing happens—twice—and yet the audience sits rapt. Why? Because the waiting becomes the metaphor. Beckett shows us that life is repetition, confusion, and the faint hope that someone or something will eventually arrive to make sense of it all.

Spoiler: It won’t.

♟ Endgame – A Chessboard of Decay

If Godot was purgatory, Endgame is the afterlife—specifically, the cluttered corner of it no one swept since the apocalypse.

In this absurd play, we meet Hamm (who cannot stand) and Clov (who cannot sit). They live in a bare, ruined room, accompanied by Hamm’s legless parents—residing in trash cans. There is no outside world. Or if there is, it’s not returning your calls.

Every line in Endgame feels like an echo.

Clov: “There’s no more painkiller.”

Hamm: “Then there’s no more painkiller.”

Clov: “Yes, there’s no more painkiller.”

Beckett’s theatre of the absurd is repetition refined to an art form. The dialogue is circular. The gestures are empty. The plot is static. And yet, it all simmers with despair that somehow dances with humor.

Because Beckett knew: in a world where nothing matters, timing is everything.

Krapp’s Last Tape – Bananas and Broken Memory

Krapp’s Last Tape – Bananas and Broken Memory

Krapp’s Last Tape might be the only play in the canon of absurd theatre to feature a man eating a banana with existential rage.

Krapp—an aging writer—sits alone with a tape recorder and a stack of reels. Each year on his birthday, he records a message to his future self. Now old, he listens to a younger version of himself talk about ambition, love, and loss. He rewinds. He replays. He sneers. He scoffs. He cries.

The past mocks him. The future forgets him.

This absurd play is a minimalist tour de force. One man, one voice, one machine—and the crushing realization that identity is a recording we keep failing to recognize.

In a world driven by progress, Beckett gives us regression—memories as betrayal, nostalgia as punishment, and technology as a stand-in therapist that always rewinds to the worst part.

Happy Days – A Woman, a Hill, and a Smile That Hurts

Happy Days – A Woman, a Hill, and a Smile That Hurts

What could be cheerier than a play called Happy Days?

Well, how about a woman named Winnie, buried up to her waist in a mound of earth, chatting endlessly to no one in particular as the sun blazes overhead and her husband (who may or may not be alive) grunts occasionally from off-stage?

And that’s Act I.

In Act II, Winnie is buried up to her neck.

Beckett’s absurd drama here is deceptively titled. Happy Days is not about joy—it’s about habitual optimism in the face of silent doom. Winnie polishes her revolver, applies lipstick, recalls random memories, and insists that “this will have been another happy day.”

She doesn’t believe it.

We don’t believe it.

And that’s the tragedy.

Winnie is all of us—sinking, smiling, and refusing to admit that the sand is rising.

Beckett’s Stage: Where Thought Loops, and Godot Ghosts

Beckett’s Stage: Where Thought Loops, and Godot Ghosts

Samuel Beckett’s theatre of the absurd was not written to be understood. It was written to be endured—like life, but with better lighting.

His plays are minimalist on the surface and cosmic underneath. He strips away action, plot, and even character until we’re left with essence: waiting, failing, enduring, repeating.

Beckett was a master absurd playwright, not because he wrote nonsense, but because he wrote truth so stripped of pretense it looked like nonsense.

And somehow, it’s funny.

We laugh when nothing happens. We giggle at the repetition. We nod at the despair. We stare at the tree. And we keep watching.

Why? Because like his characters, we, too, are waiting.

PART 6: Harold Pinter – Pause. Repeat. Menace.

Keyphrase: Pinteresque style in absurd drama

“Pinter taught us that if you say less, it means more. Or nothing. Or something.”

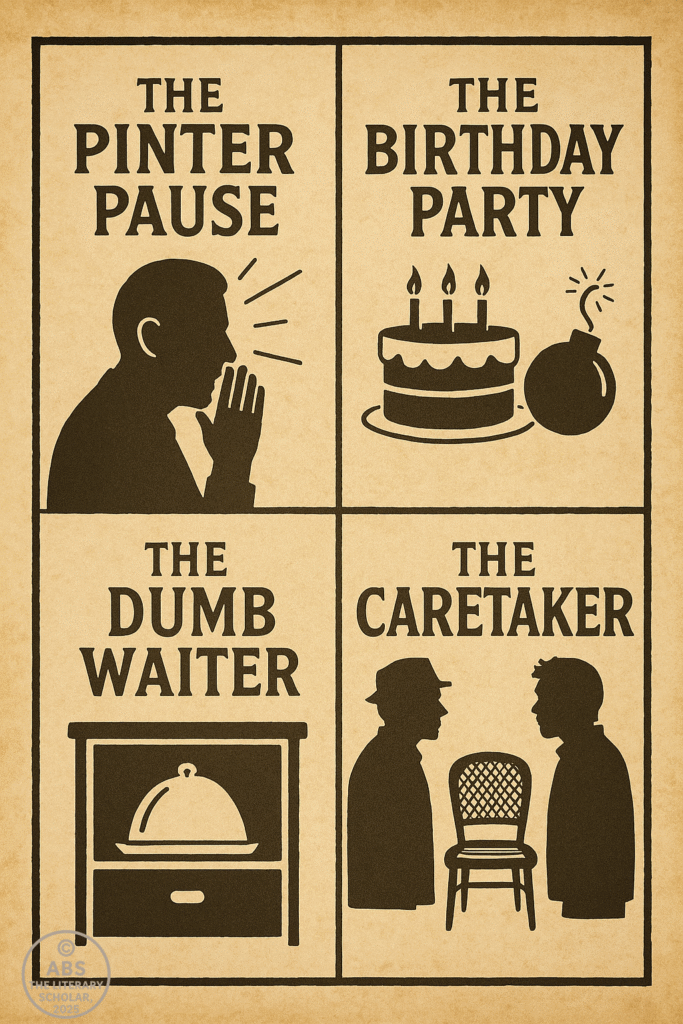

The Pinter Pause – Silence with a Switchblade

The Pinter Pause – Silence with a Switchblade

Imagine a scene. Two people in a room. One speaks. The other doesn’t. The silence stretches. Your spine tingles. Did something just happen? No? Then why are you sweating?

Welcome to the Pinteresque style in absurd drama, where what’s not said matters more than entire Shakespearean soliloquies.

The “Pinter Pause” is legendary. A beat. A breath. A black hole in dialogue. But in that void lies power, suspicion, and a creeping sense that someone’s lying—or worse, being honest.

Harold Pinter’s absurd plays didn’t need bizarre props or surreal locations. He gave us the absurdity of ordinary spaces—a room, a flat, a basement—then filled them with language that evaded truth like it owed it money.

In absurd theatre, words often collapse. In Pinter’s absurd drama, they betray. They hide the wound, then prod it.

The Birthday Party – A Cake with Gaslighting Icing

The Birthday Party – A Cake with Gaslighting Icing

In The Birthday Party, Pinter takes us to a seaside boarding house so unassuming it practically screams “emotional damage incoming.”

Stanley, the guest of honor, insists it’s not his birthday. His landlady insists it is. Two strangers arrive—Goldberg and McCann. They interrogate him. The questions make no sense. The answers make less. They break him. They take him away.

We never find out who they are. Or why they came. Or what they wanted.

Welcome to absurd drama, Pinter-style—where the characters play psychological hopscotch and the audience gets no rules.

The brilliance of this absurd play lies in its familiarity. It’s not surrealism—it’s domestic dread. It’s absurdity hiding in the wallpaper.

By the end, Stanley is broken, his identity shattered. No monsters. No rhinoceroses. Just two men, a few pauses, and an unspoken agreement that reality is now optional.

The Dumb Waiter – Suspense in the Service Industry

The Dumb Waiter – Suspense in the Service Industry

Two hitmen—Ben and Gus—wait in a basement for their next job. They talk. They bicker about matches, tea, semantics. Then the dumb waiter sends down food orders. There’s no kitchen. No staff. No explanation.

This is absurd theatre in a suit and tie—all the eerie existentialism, none of the exotic surrealism. Just two working-class men waiting for instructions from above—literally and thematically.

Gus starts to question things. The orders don’t make sense. The silence grows heavier. The menace intensifies. And then—the twist.

Pinter uses absurdity as subtle sabotage.

This isn’t Beckett’s void or Ionesco’s chaos. It’s bureaucracy with a knife in its back.

The real dumb waiter isn’t the mechanical lift.

It’s the one who keeps waiting for meaning in a world designed to withhold it.

The Caretaker – Identity for Rent, Confusion Free

The Caretaker – Identity for Rent, Confusion Free

The Caretaker is the story of three men and one extremely symbolic room. Aston brings in Davies, a homeless man. Mick, Aston’s brother, enters and toys with Davies psychologically. There’s a bag. There’s a Buddha statue. There’s a lot of talk. But nothing. Actually. Happens.

What we get is a slow, devastating dissection of identity, illusion, and interpersonal warfare.

Davies changes his story every few lines. Aston tells a traumatic tale with eerie detachment. Mick rants like a salesman on the brink of collapse.

By the end, nobody knows who anyone is. Least of all the audience.

This is Pinter’s absurd drama at its most poetic and cruel. A room becomes a battlefield. A name becomes a lie. A chair becomes a throne, a weapon, and a placeholder for whatever ego is currently talking.

Pinteresque Absurdity: Meaning on Mute

Pinteresque Absurdity: Meaning on Mute

Pinter didn’t shout. He whispered.

And in that whisper lived entire absurd plays that unpacked power, silence, fear, and identity with surgical precision.

He took the surrealism of absurd theatre and injected it into everyday life—making it scarier. You can avoid trees and rhinos. But you can’t escape a conversation where the pauses accuse you.

Where Beckett gave us purgatory, and Ionesco gave us nonsense, Pinter gave us the office, the apartment, the boarding house—familiar places turned unfamiliar through language itself.

His style became its own adjective: Pinteresque—meaning ominous, clipped, disturbingly normal.

If absurd drama is a rejection of logic, Pinter’s plays are a refusal to give closure.

The characters speak. Then don’t.

They know things. Then deny them.

They exist. Or maybe they don’t.

And you, the audience, lean forward, listening—because silence has never been this loud.

Part 7: The Absurd Playwrights’ Club – Genet, Stoppard, Albee, and Friends

Other Absurd Companions – The Avant-Garde Posse

The Absurdist Gathering

In the realm of theater, a curious group of playwrights emerged in the mid-20th century—each with an utterly unique take on the world, yet bound by their shared belief that the human condition is far from logical, and often, unintelligible. This “Absurd Playwrights’ Club,” though uninvited to the halls of reason, ushered in works that left audiences questioning everything, particularly themselves. These playwrights didn’t just challenge the structure of plays; they reimagined reality itself, demanding that the audience participate in their confusion.

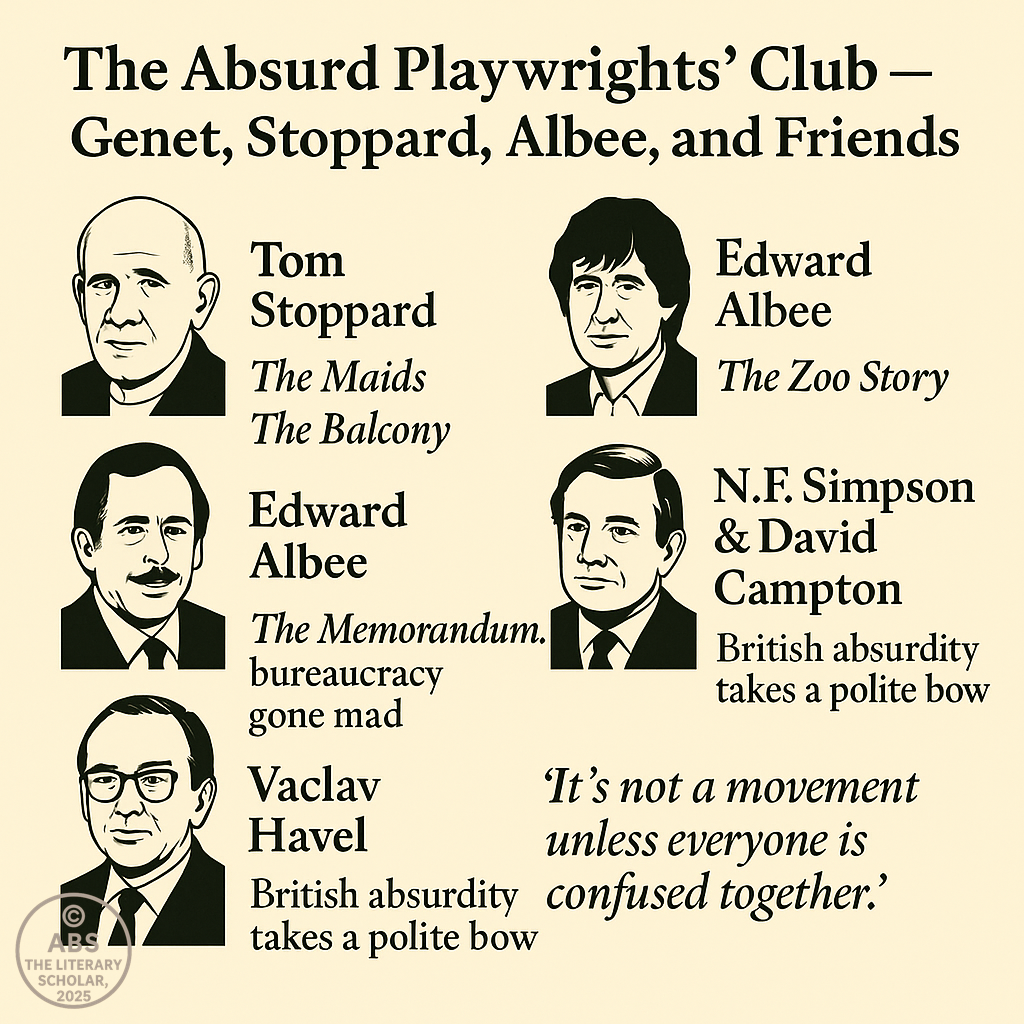

While Samuel Beckett remains the poster child of the absurdist movement, there are many others who didn’t shy away from pushing boundaries and exploring the strange and surreal facets of human existence. Among them are Jean Genet, Tom Stoppard, Edward Albee, Vaclav Havel, and British absurdists like N.F. Simpson and David Campton. Each one brought a distinct flavor to absurdity, blending humor, discomfort, and deep philosophical exploration. In this article, we take a dive into their worlds—each a unique brand of madness that, ironically, mirrors the chaos of our own.

Jean Genet – The Maids, The Balcony

Jean Genet, a playwright who was no stranger to controversy, is considered one of the most provocative figures in the Absurd Playwrights’ Club. With plays like The Maids and The Balcony, Genet blends absurdity with a dark sense of the erotic and a sharp critique of societal norms. His works often blur the line between reality and illusion, where characters are trapped in roles they cannot escape.

In The Maids, Genet portrays two sisters who role-play as their mistress, adopting her persona to subvert their reality. This exploration of power dynamics and submission weaves an absurdly distorted reflection of class and gender. The maids’ rebellion, however, is illusory—just as the societal roles they mimic are fleeting and unnatural. Genet’s work draws the audience into an unsettling realm where nothing is quite as it seems, and no one can escape their own absurd entrapment in society’s expectations.

Similarly, in The Balcony, Genet explores the fantasies of power through a brothel that specializes in recreating political and military scenarios. The absurdity of people paying to role-play as leaders is a biting commentary on the performative nature of authority. Genet challenges the idea of power as a construct that can be enacted, stripped of its legitimacy, and reduced to mere playacting. In his absurdist world, even the most serious of roles are nothing more than theatrical masks.

Tom Stoppard – Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead

Tom Stoppard, one of the sharpest minds in contemporary absurdist theater, masterfully demonstrates the interplay of fate and free will in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. This 1966 play takes two minor characters from Shakespeare’s Hamlet and flips the script, focusing on their confusion and futility as they try to make sense of their roles in the greater scheme of things.

The play is suffused with existential humor as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, caught in a cosmic game of chance, struggle to understand their existence. Their endless questioning and failure to comprehend their situation reflect the absurdity of human life—caught between the desire for meaning and the absence of it. The existential confusion they experience mirrors our own: when we fail to grasp the overarching narrative of our lives, the randomness of existence itself becomes an endless game of chance.

Stoppard’s intricate use of wordplay and his deep philosophical insights elevate Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead beyond mere comedy. In his absurd universe, even death becomes just another act in an endless play. The characters’ inability to understand their place in the universe amplifies the absurdity of human life itself.

Edward Albee – The Zoo Story

Edward Albee, known for his hard-hitting psychological exploration of the human psyche, crafted The Zoo Story as an absurdist examination of isolation and communication. The play features Jerry, a man on the fringes of society, and Peter, a seemingly ordinary man, who are brought together by an unexpected encounter in Central Park. The two men engage in an increasingly bizarre conversation that explores the themes of existential alienation, the breakdown of social norms, and the meaning of human existence.

While The Zoo Story may not be as overtly absurd as Beckett’s work, it nonetheless uses the absurd to reveal the isolation and desperation that lie beneath the surface of contemporary life. The characters’ disjointed conversation and the violence that erupts towards the end of the play serve as a stark reminder of how absurd it is that we, as human beings, often fail to communicate with one another meaningfully, even when we long for connection.

Vaclav Havel – The Memorandum

Vaclav Havel, a playwright and dissident who later became president of Czechoslovakia, brought a unique brand of absurdism to the stage with his play The Memorandum. This work focuses on a bureaucratic nightmare where the protagonist, Josef, tries to navigate a world increasingly dominated by absurd rules and the dehumanizing effects of bureaucracy.

In The Memorandum, the language itself becomes an absurd tool of control. The play centers on a company that implements a new language system called Ptydepe, a constructed language that is supposed to make communication more efficient but only ends up making communication impossible. The play, full of Kafkaesque absurdity, illustrates the madness that occurs when systems designed for efficiency end up strangling meaning and human connection. Havel’s critique of bureaucratic systems is not just a political commentary but a reflection on the absurdity of trying to structure human existence in a way that ignores the complexities of individual lives.

N.F. Simpson & David Campton – British Absurdity Takes a Polite Bow

In Britain, absurdity found its own peculiar flavor in playwrights like N.F. Simpson and David Campton. Simpson’s A Resounding Tinkle is a quintessential example of British absurdist humor—characterized by its polite, seemingly banal characters caught in a whirlwind of irrational situations. The absurdity here is not shouted at the audience; it is presented with a tea-and-cucumber-sandwich gentleness that makes it all the more disorienting.

Simpson’s characters, obsessed with trivialities, remain unfazed by the growing absurdity around them, which only amplifies the disorienting nature of their world. This British absurdity, with its genteel politeness, works as a subtle but poignant critique of the ridiculousness inherent in social and class structures.

David Campton’s plays, such as The Lunatic View, adopt a similar approach to absurdity, focusing on the trivialities of life that take on massive, surreal proportions. In Campton’s world, the polite bow of absurdity becomes a means of reflecting the way social conventions stifle individuality and creativity. The juxtaposition of the mundane with the surreal is a hallmark of the British absurdists, who take a more restrained approach to exploring existential absurdity than their Continental counterparts.

Conclusion: The Absurd Playwrights’ Collective Mind

“It’s not a movement unless everyone is confused together.” This quote encapsulates the essence of absurdist theater. These playwrights, whether it was Genet’s political critique, Stoppard’s intellectual games, Albee’s exploration of communication, Havel’s political absurdity, or the quiet chaos of Simpson and Campton, created a theatrical world that invited confusion and discomfort—and in that confusion, there was profound clarity. By taking on the absurd, they revealed the chaotic, fragmented, and often nonsensical nature of human existence.

While the Absurd Playwrights’ Club might not have set out with a unified manifesto, their collective works remind us that the human experience, at its core, is full of absurdity. The absurd, they argued, is not something to be avoided; it is something to be embraced as a reflection of the world’s inherent madness. Through laughter, discomfort, and bewilderment, these playwrights turned the stage into a mirror that reflects not just the absurdities of their characters, but of the audience itself. In their works, the absurdity of life becomes not just a theme but a call to acknowledge the bewildering, irrational nature of our own existence.

Language, Meaning, and Miscommunication

Language in Theatre of the Absurd

Semantic Collapse – Why No One Understands Anyone Anymore

In the Theatre of the Absurd, the language of communication is in a constant state of unraveling. The plays are filled with characters whose dialogues seem endless but lead nowhere, whose words are as fragmented as the world around them. This is what we can call “semantic collapse,” where language loses its meaning, and communication becomes a futile exercise. Characters often speak in circles, repeating themselves and failing to convey anything of substance.

In Absurdist theater, language is no longer a tool of clarity or a means to solve problems. Instead, it becomes a symbol of disconnection, a device that exposes the hollowness of human existence. This breakdown of communication is seen in works like Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, where the characters, Vladimir and Estragon, spend much of the play conversing in a fragmented, almost nonsensical manner. Their words don’t build toward understanding or clarity, but rather deepen their confusion and existential isolation. This breakdown of communication echoes the absurdity of trying to make sense of a meaningless world.

The language of the Absurdists refuses to tie itself to any clear meaning, forcing the audience to confront the absurdity of trying to communicate in a world that seems fundamentally incoherent. As a result, the plays leave us with more questions than answers, and yet, in this very ambiguity, they point to the futility of seeking meaning in a senseless universe.

Verbal Repetition & Illogic – The Musicality of Nonsense

One of the striking features of absurdist dialogue is the constant repetition of phrases and words. This repetition is not a rhetorical device; it’s a tool that amplifies the absurdity of communication. It serves to highlight the illogic of the characters’ existence, reinforcing the idea that their lives are perpetually caught in a loop—much like their conversations.

In works like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by Tom Stoppard, the characters engage in verbal ping-pong, batting words back and forth in an endless cycle. Their repetitive exchanges seem to have no purpose beyond the sheer act of talking. Yet, this repetition has a musical quality to it, creating a rhythm that seems to build toward something—until it doesn’t. There’s a bizarre beauty in the way nonsense unfolds in the Absurdist theater, where the repetition of meaningless words becomes the music of despair, a soundtrack to the futility of human existence.

Beckett’s Endgame also relies heavily on repetition, not just of words, but of actions and thoughts. The characters repeat themselves, sometimes verbatim, creating an uncomfortable but compelling pattern. The audience becomes aware that there is no progression, no closure—only the ceaseless ticking of time, a reminder that the struggle to communicate is in itself futile. The music of nonsense, in this case, is both haunting and absurd, making us reflect on the nature of meaning itself.

Dialogue That Doesn’t Dialogue – Characters Talk At, Not To Each Other

In the Absurdist play, dialogue often isn’t about conversation in the traditional sense. The characters don’t engage in meaningful exchange. Instead, they talk at each other, never truly listening or responding in a way that would facilitate understanding. This lack of genuine dialogue is a reflection of the existential alienation and emotional isolation that is central to the Absurdist worldview.

Take The Zoo Story by Edward Albee, where the protagonist, Jerry, initiates a conversation with Peter, a seemingly ordinary man. Instead of forming a connection or engaging in a mutual exchange, Jerry dominates the conversation, spewing out his existential musings without concern for Peter’s responses. Peter, in turn, remains passive, offering occasional, disinterested remarks. Their conversation is more of a monologue on both sides, as each character speaks over the other, never truly addressing or understanding one another.

This breakdown of true dialogue is characteristic of Absurdist theater. Words are tossed into the void, but they don’t land with any meaning or purpose. This disconnect is a powerful statement on the difficulty, if not impossibility, of human communication in a world that doesn’t make sense. The characters’ failure to listen to each other echoes the theme of existential loneliness, showing that no matter how much we talk, we are always isolated.

Words as Weapons & Wobbles

In the Absurdist world, language often functions as a weapon. Words are hurled like daggers, not to wound physically, but to inflict psychological harm or emphasize the absurdity of existence. The characters wield their words like knives, yet these words fail to have the desired impact. Instead of breaking down barriers or creating understanding, they only serve to highlight the futility of their actions.

In The Maids by Jean Genet, the language is used to reinforce the power dynamic between the two sisters and their mistress. The maids adopt their mistress’s language, but in doing so, they perpetuate the artificiality of their roles. Their words are weapons in their attempt to subvert the social hierarchy, but they are also hollow, unable to bring about real change. Their words wobble between power and impotence, showing that language, when stripped of meaning, loses its force and becomes a tool of delusion rather than liberation.

This wobbling nature of language is also evident in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, where the words spoken by Vladimir and Estragon often seem to lose their meaning mid-sentence. Their thoughts are disjointed and unfinished, reflecting the instability of language itself. The characters’ attempts to use words as instruments of communication are ultimately futile, underscoring the Absurdists’ belief that words, like everything else, fail to capture the full complexity of human experience.

“If Shakespeare Gave Us Eloquence, the Absurdists Gave Us Existential Buffering”

This quote captures the essence of the Absurdists’ approach to language. While Shakespeare’s works are renowned for their eloquence, filled with poetic beauty and intellectual depth, the Absurdists gave us something quite different—an unflinching look at the emptiness of language. Where Shakespeare used eloquent speech to reveal profound truths about the human experience, the Absurdists used fragmented, nonsensical dialogue to reveal the futility of those very attempts at understanding.

The Absurdists’ use of language doesn’t seek to explain or resolve the existential crises they portray. Instead, it serves as a buffer—a cushion between the audience and the raw, overwhelming absurdity of life. In their world, language is not a bridge between people or a means of communicating meaning; it’s a way of buffering the absurdity of existence, keeping us at a safe distance from the terrifying truth of our meaningless lives.

Conclusion: The Theater of Miscommunication

Language, in the Theatre of the Absurd, is less a means of communication and more a reflection of the inherent chaos of existence. The characters are trapped in a web of words that fail to deliver meaning, and yet, it is through this very failure that the Absurdists offer a profound commentary on the human condition. Language, instead of providing clarity, becomes a tool of confusion, a symbol of the breakdown of all systems, whether social, political, or personal.

In a world where words wobble, repeat, and fail to connect, the Absurdists force us to confront the limitations of language itself. Their works invite us to experience the discomfort and futility of communication, not as a mere theatrical device, but as a reflection of the deeper, existential disconnect at the heart of our lives. Language, in the Absurdist theater, is not just a barrier to understanding—it is a mirror, reflecting the chaotic, fragmented nature of human existence.

Part 9: The Audience as Co-Sufferer

Impact of Theatre of the Absurd on Audience

Why People Laughed (and Then Questioned Their Lives)

Theatre of the Absurd is built on a foundation of confusion, chaos, and disorientation. It often starts with a laugh—a moment of humor or absurdity that catches the audience off guard. This humor, however, is not typical. It’s not about punchlines or clever wordplay. Instead, it’s a dissonant laughter that arises from a sense of absurdity that is both funny and unsettling. Characters struggle with their existence, and the audience laughs, unsure of whether they should be laughing at the absurdity of the situation or at their own helplessness to make sense of it.

Absurdist plays like Beckett’s Waiting for Godot or Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead play with the audience’s expectations by layering humor with discomfort. The laughter that arises in these moments is often nervous—a response to the absurdity of existence that feels too real. As the audience laughs, they are suddenly confronted with the fact that this absurdity is not confined to the stage—it is mirrored in their own lives. This laughter, which begins as a coping mechanism for the strangeness on stage, eventually gives way to deeper existential reflections about the meaning (or lack thereof) in their own world. The audience laughs at the characters’ plight, only to realize they are laughing at their own.

Alienation Effect vs Absurd Experience

One of the most significant impacts of Absurdist theatre on the audience is the alienation effect—a concept famously championed by Bertolt Brecht, though adapted differently by the Absurdists. In traditional theatre, the goal is to create empathy and emotional connection. Absurd theatre, however, seeks to distance the audience from the emotional drama unfolding on stage. The alienation effect is intended to remind the audience that what they are witnessing is not a slice of reality, but a constructed piece of theatre designed to provoke thought and reflection. The audience is meant to be disengaged from the story emotionally, instead being prompted to critically engage with the existential themes at play.

However, in Absurd theatre, this effect often gives way to a unique experience—an absurd experience. The audience feels both alienated from the characters and yet drawn into their absurd struggles. The experience becomes intensely personal, even if the play itself seems to be a series of random events. The disconnection established by the alienation effect makes the experience of the theatre all the more haunting and confrontational. The audience becomes both detached from the narrative yet involved in a personal, existential journey that mirrors the characters’ own.

Emotional Dissonance – Confusion as Catharsis

In the Theatre of the Absurd, the audience is not merely entertained—they are disrupted. They enter the theatre expecting a typical emotional arc but are met with a series of unpredictable and disjointed experiences. The absurdity of the narrative itself creates a profound emotional dissonance. The audience is pulled between laughter, discomfort, confusion, and alienation, all while trying to piece together the fragmented world the playwright has created. This emotional conflict is what leads to the catharsis that Absurd theatre provides—not through resolution or plot development, but through the very process of confronting confusion.

The confusion becomes a form of catharsis because it forces the audience to confront their own inability to find meaning. In traditional theatre, catharsis often arises from the resolution of conflict. In Absurdist theatre, however, the unresolved becomes a cathartic experience. As the audience wrestles with meaninglessness, they are forced to face the existential void that mirrors the inner turmoil they may feel in their own lives. In many ways, this confusion offers a kind of emotional release, a cleansing of the anxiety that arises from trying to impose order on an inherently chaotic world.

Critics’ Breakdown: ‘It’s Brilliant!’ ‘It’s Nonsense!’ ‘It’s Both!’

The reaction to Absurdist theatre has always been polarized. Critics are often split in their assessment: one side calls it brilliant, while the other dismisses it as nonsense. But this breakdown in critical reception is precisely what makes Absurd theatre so impactful. It resists categorization. It defies traditional narrative expectations and subverts conventional storytelling structures. As a result, it pushes the boundaries of what theatre can do, both artistically and philosophically.

The tension between these two critical responses—praise for brilliance and accusations of nonsense—reflects the central paradox of the Absurd: it is both meaningless and deeply profound. The brilliance of Absurd theatre lies in its ability to convey existential truths without offering clear answers. Its nonsense is often a reflection of the absurdity of human existence itself: an existence that does not offer easy explanations or tidy resolutions. The brilliance of Absurd theatre, therefore, lies in its very nonsense. It teaches us to live with ambiguity, to exist in a world where meaning is elusive, and to laugh at the uncertainty that surrounds us.

“Watching Absurd Theatre is Like Watching Your Own Thoughts Argue During Insomnia.”

This quote perfectly encapsulates the impact of Absurd theatre on the audience. Just as insomnia causes the mind to churn with thoughts, Absurd theatre churns the audience’s thoughts, forcing them to confront the fragmentation of their own understanding. The theatre becomes a mirror, reflecting the chaotic nature of the human mind—a mind that, much like the characters on stage, is endlessly grappling with meaning and purpose in a world that offers neither.

In the same way that insomnia leads to mental agitation, Absurd theatre leads to emotional and intellectual unrest. The audience is left not with answers, but with questions—and this questioning is where the catharsis lies. Absurd theatre is not about resolving the confusion but about embracing it, acknowledging that the very act of questioning is a form of existential survival.

Conclusion: The Audience as Co-Sufferer

Absurd theatre transforms the audience from passive observers into active participants in the chaos and confusion it presents. The audience is co-sufferers, not in the traditional sense of sympathizing with a tragic hero, but in the sense of experiencing the absurdity of life alongside the characters. Through laughter, confusion, alienation, and emotional dissonance, the audience is drawn into a shared experience of existential questioning. The impact of Absurd theatre is not just in what it says, but in what it forces the audience to feel—the tension between meaning and meaninglessness, coherence and chaos. It is a theatre of disruption, where the audience’s own thoughts and emotions are as fragmented as the world on stage, and in that fragmented experience, there lies a profound catharsis.

Part 10: Absurdity Today – Still Waiting for Something

The Legacy of Theatre of the Absurd

Absurdism in Postmodernism – From Beckett to Memes

The Theatre of the Absurd, once a groundbreaking form of dramatic expression, has transcended the stage and found its way into the digital and cultural fabric of the 21st century. What began with the likes of Beckett, Ionesco, and Genet has evolved into a broader postmodern sensibility that encompasses everything from high art to internet memes. Absurdism, originally seen as an avant-garde challenge to traditional narratives, has now become a cultural lingua franca, feeding into the chaos and fragmentation of modern life.

Postmodernism embraces the fragmentation of meaning, the idea that there is no single narrative or ultimate truth. The very randomness and playfulness of internet memes, for instance, are the digital descendants of the absurdist theater. Memes exist in a space where context is fluid, and meaning is constantly shifting. One moment, a meme will provide a chuckle, and the next, it will dissolve into absurdity, leaving the viewer unsure of whether to laugh or to reflect on the sheer emptiness of modern communication. Beckett’s Waiting for Godot might not seem all that different from the fleeting nature of viral content—it’s about waiting, it’s about searching for meaning, but ultimately, it’s about finding nothing at all.

Absurdism in postmodernism questions the structure of life and culture just as absurd theater once questioned the form of drama itself. Through meme culture, we continue to wait for something: an answer, a resolution, a reason—while we remain deeply aware that no final explanation is ever truly possible.

Modern Echoes – TV, Film, and Internet Absurdity

Absurdity didn’t die when the curtain closed on Beckett’s plays. In fact, it found new homes in the unlikeliest places, where television, film, and the internet continue to explore the absurdities of modern existence. Shows like BoJack Horseman, Charlie Kaufman’s films, and even Black Mirror carry the torch of absurdist theatre into our everyday lives, wrapping us in narratives that leave us both laughing and unsettled.

BoJack Horseman, an animated series that aired on Netflix, presents a deeply flawed anthropomorphic horse navigating Hollywood, addiction, and self-doubt. The absurdity in the series isn’t confined to the bizarre premise—it’s woven into the frenetic, often nonsensical plotlines that highlight the emptiness of fame, fortune, and personal growth. In BoJack, absurdity is used to reveal deep existential truths. The endless cycles of self-sabotage, combined with an inability to escape from his own flawed nature, echo the themes of futility and alienation found in Beckett’s works.

Similarly, Charlie Kaufman, the mind behind films like Being John Malkovich and Synecdoche, New York, takes absurdism to a more philosophical level. Kaufman’s films reflect the absurd complexity of modern life—where identity is a shifting illusion, and we are perpetually trying to make sense of a universe that doesn’t make sense. Kaufman’s work, like Beckett’s, confronts us with disjointed narratives, forcing us to reckon with the nonsensical nature of existence.

And in the world of television, Black Mirror explores the ways in which technology amplifies the absurdity of the human experience. The show’s episodes often offer exaggerated visions of the future, where technology traps people in cycles of dissatisfaction and disconnection, much like the repetitive, circular dialogue in Absurdist plays. Here, technology is the modern manifestation of the existential void—an endless feed of triviality that distracts us from the deeper absurdities of life.

BoJack Horseman, Charlie Kaufman, Black Mirror – Godot Got Digital

If there’s one thing we’ve learned in the digital age, it’s that absurdity isn’t going anywhere. In fact, it’s gone digital—and it’s now in your pocket. The influence of Absurdist theatre can be seen clearly in shows and films that blend existential angst with the surreal and illogical.

BoJack Horseman, with its anthropomorphized animals and cynical commentary, speaks to the absurdity of fame and the hollow pursuit of happiness in modern life. The absurdity of self-perception, so evident in Absurdist theatre, is amplified here, as the characters are trapped in a loop of their own making, unable to change or escape their destructive behaviors.

Charlie Kaufman’s films, like Anomalisa and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, dig deep into the fragmented nature of self-awareness. Kaufman plays with memory, identity, and time, creating worlds where the logic of reality continually breaks down, and we are left wondering whether anything has any true meaning. Kaufman’s films, like Absurd theatre, don’t provide neat resolutions—they leave us in a state of existential discomfort that mimics the theatre’s audience, forced to reflect on our own inability to make sense of existence.

In Black Mirror, the absurdity is rooted in technology’s increasingly dystopian impact on society. Each episode, like an absurdist play, leaves viewers questioning their understanding of the world and their place in it. Whether it’s the absurdity of social media culture or the dehumanizing effects of surveillance, Black Mirror is a modern-day exploration of the themes of alienation and futility that the Absurdists once portrayed in the most stripped-down, theatrical ways.

Why Absurd Theatre Still Matters – The World’s Still Ridiculous

Despite all the technological advances, the information overload, and the hyper-connected world, the fundamental truths that Absurdist theatre exposed are still with us. The world is still ridiculous. We live in an era of contradictions, where meaning feels more elusive than ever. Absurdism hasn’t died—it’s merely adapted to the new form of confusion and uncertainty we face today.

Absurd theatre remains relevant because it reflects the absurdity of human existence. Whether it’s digital culture, political disillusionment, or social alienation, the themes explored in Absurdist plays are still alive and kicking. In a world where everyone is struggling to find meaning, Absurdist theatre serves as a reminder that life itself has no clear answers—and that, in fact, embracing the absurdity may be the only way to truly live.

Absurd theatre matters because it continues to hold up a mirror to our modern lives, showing us the inherent contradictions of our existence. As long as we continue to search for meaning in a world that seems inherently meaningless, Absurdist theatre will remain a vital part of our cultural landscape—laughing at our chaos while forcing us to confront the truth that we are still waiting for something, even though we may never know what it is.

“Absurd Theatre Didn’t Die. It Just Logged In and Said: ‘Buffering…’”

This quote sums up the legacy of Absurd theatre perfectly. Absurdism didn’t disappear—it merely found new ways to infiltrate our lives. Just as we now wait for the internet to load, we are still waiting for meaning to emerge from the chaotic web of modern life. The more connected we become, the more absurd the world seems, and the more we find ourselves buffering in search of something deeper. Absurd theatre is alive and well, only now it’s buffering in a digital age.

ABS Closing Note:

“Absurdity, once a distant echo in the theatre, now resides at the heart of our digital age, lurking in the corners of our memes, films, and fractured narratives. And yet, the essence of Absurd Theatre remains the same: a constant, comical, and often painful reminder that the search for meaning is just as perplexing as the universe itself.”

ABS, The Literary Scholar

Folding the scroll…

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance