By ABS, The Literary Scholar

(Who believes that if life is absurd, you may as well squint at the sun and be late to your own trial)

Some novels begin with a bang. Others begin with a body. The Stranger begins with a sentence that feels like both and neither:

“Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.”

And with that, Albert Camus launches a quiet literary revolution—by handing us a narrator who cannot be bothered. Not by death, not by God, not by guilt, and certainly not by narrative conventions.

Welcome to the sunlit void of Meursault, the French Algerian clerk whose primary hobby is not caring, and whose defining quality is perfectly symmetrical apathy. He is the anti-hero who yawns at fate, blinks at grief, and accidentally becomes a philosophical icon by being too tired to pretend.

Meursault is not emotionally unavailable. He is emotionally off-grid. He does not cry at his mother’s funeral. He does not weep for love, nor plead for life. He smokes next to her coffin, drinks coffee with milk, and worries mostly about being hot.

He’s not heartless. He’s sun-struck, sand-burned, and bored to the marrow.

“I opened myself to the gentle indifference of the world.”

This isn’t nihilism with edge. It’s nihilism with a sun hat and sweaty armpits.

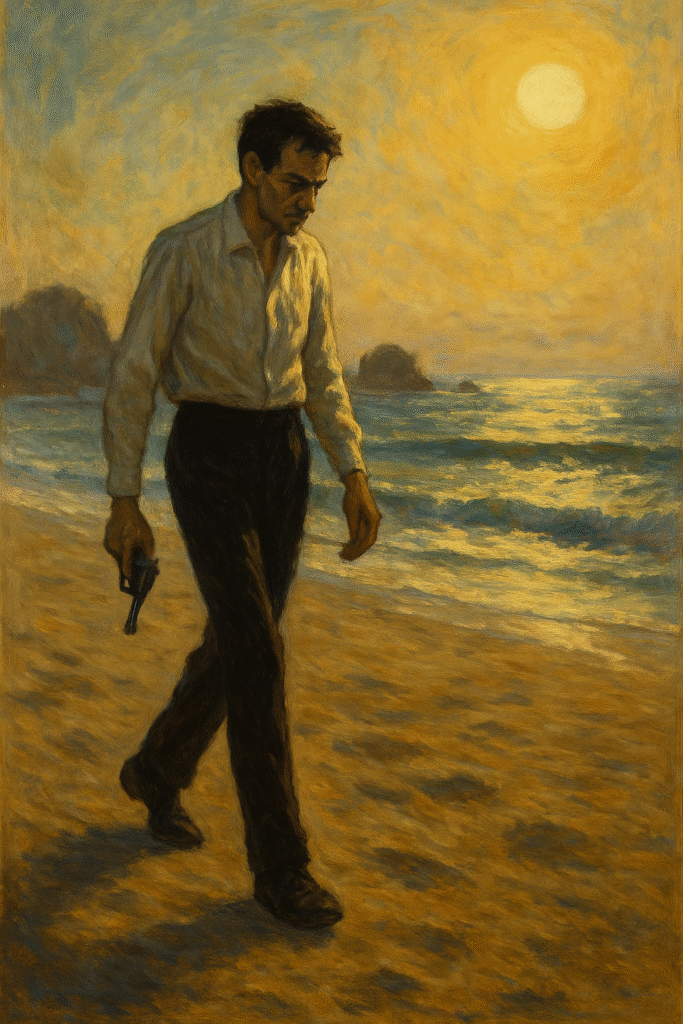

If The Stranger were a murder mystery, the crime would already be solved. If it were a courtroom drama, the drama would be replaced with sighs. Meursault shoots a man. Yes. An Arab, Camus tells us—never named. On the beach. Five bullets. One gun. No motive beyond:

“It was because of the sun.”

The heat. The glare. The disorienting shimmer of light off a knife.

Camus doesn’t give us psychology. He gives us photons and absurdity.

We do not understand Meursault. We observe him. Like watching a lizard blink, or a rock bask.

After the murder, Meursault is imprisoned. And his trial becomes a tragicomedy of misunderstanding.

They’re not judging the act. They’re judging the attitude.

Not what he did. But how chill he was while doing it.

He didn’t cry at the funeral.

He didn’t pray in prison.

He didn’t show remorse.

He accepted death like a man accepting heatstroke: calmly, vaguely annoyed.

And so, naturally, he’s sentenced to death.

“I had only a little time left and I didn’t want to waste it on God.”

Camus’s genius is this: he hands us a character who offends not because of evil—but because he refuses to perform grief.

There is, buried beneath the dry tone and drier sand, a quiet rebellion. Meursault lives in a world that demands emotion on cue, meaning on command, performance at every turn. And instead, he says: No thank you. I’ll sit in the sun.

“Since we’re all going to die, it’s obvious that when and how don’t matter.”

That’s not despair. That’s absurd clarity.

Camus, philosopher of the absurd, doesn’t write Meursault to horrify. He writes him to expose our illusions. The illusion that morality is always visible. That remorse is always loud. That belief is always necessary.

The Stranger does not ask, “What kind of man kills?”

It asks, “What kind of world kills a man for not playing along?”

And so Meursault becomes more than a man. He becomes a metaphor.

A mirror held to a society obsessed with ritual, with rules, with emotional choreography.

And Camus, calmly, dismantles it with a man who simply doesn’t dance.

By the final pages, Meursault embraces death. Not as a punishment. But as an endpoint that finally makes sense.

He stares into the night sky. The stars do not twinkle for him.

The universe doesn’t blink.

And in that silence, he feels peace.

“I felt that I had been happy and that I was happy again.”

Imagine that: a man facing execution—and his final thought is contentment.

Not because of a higher power. Not because of redemption.

Because, perhaps, for the first time—he is honest.

And somewhere, ABS, The Literary Scholar, stands at the edge of a sunlit courtroom, not blinking, not sweating, and not faking what can’t be felt, whispering, “Perhaps the truest rebellion is not passion—but refusal.”

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

(Still searching for shade in a world that prefers sun-drenched illusions)

(Still not crying on command)

(And who believes that Meursault didn’t lose his soul—he just declined the script)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance