The Picture of Dorian Gray: When the Soul Poses for a Portrait

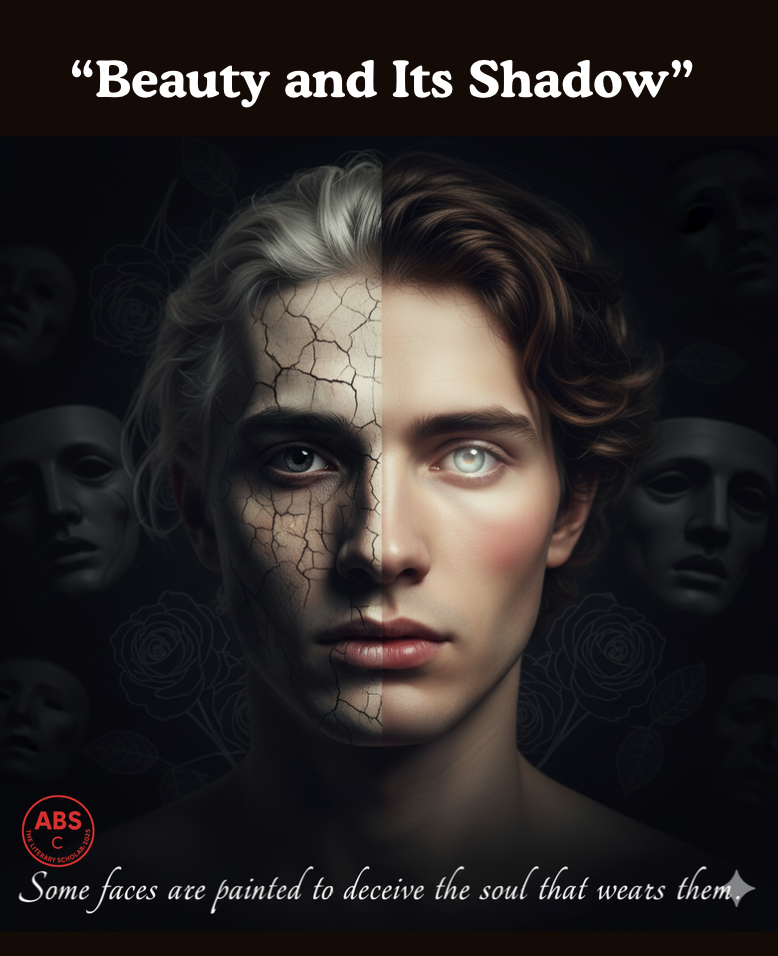

There are sins that roar and sins that whisper. Dorian Gray’s whispered beautifully. He began as a sketch of innocence, admired, adored, and almost unreal. By the time the canvas caught its final shade, innocence had become memory, and beauty had learned to lie.

Oscar Wilde wrote The Picture of Dorian Gray with the precision of a jeweller and the mischief of a juggler. It glitters on every page, but the sparkle conceals the bruise. Beneath its graceful wit lies a philosophy that delights in contradiction, that art may rise above morality even as morality decays beneath art.

The Making of a Mirror

Dorian is not born wicked. He is born lovely, which, in Wilde’s universe, is often the more dangerous condition. The world falls in love with him, and he with himself. His tragedy begins with admiration. Lord Henry Wotton, ever the eloquent corrupter, merely gives him the words to express his vanity. He preaches the gospel of indulgence, and Dorian listens as one might listen to music, enchanted, unguarded, unthinking.

“The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.”

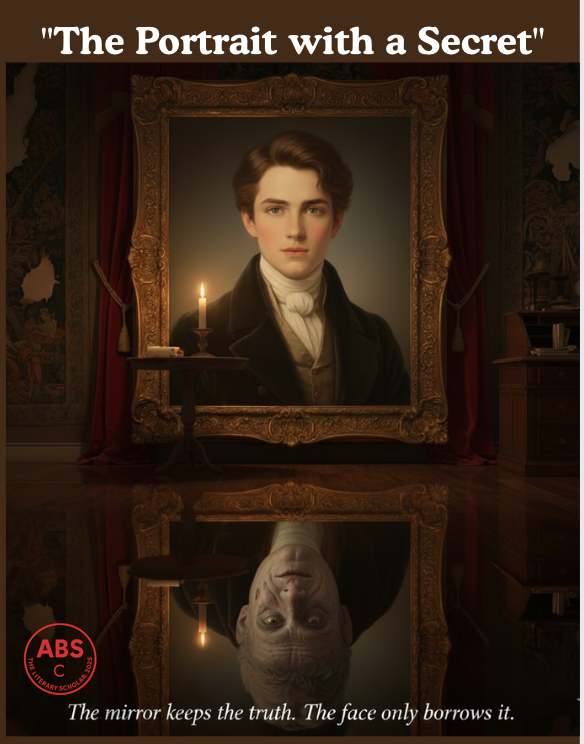

It is in that moment before the portrait that the soul is lost, not through sin but through suggestion. “If only the picture could change, and I could be always what I am now,” Dorian murmurs, and the wish becomes the wound. Wilde, in his supreme irony, allows it. The painting takes on the burden of conscience, while its owner drifts unblemished through corruption.

From then on, the portrait becomes the moral shadow that follows the figure unseen. It records what society cannot. Every cruelty adds a line to the face, every deception deepens the darkness of the eyes. It is the diary of a soul written in pigment. When Dorian hides it away, he hides the truth of himself. But truth, like art, is patient.

The Philosopher of Pleasure

Lord Henry continues to charm the narrative with his graceful epigrams. His sentences are perfumes that intoxicate. His mind is a cabinet of paradoxes. Every word sparkles, every thought undermines another. Wilde gives him the role of Mephistopheles in evening clothes, polite, brilliant, and unashamed.

“To be natural is such a very difficult pose to keep up.”

Henry is the voice of aesthetic hedonism, the worshipper of sensation. To him, sin is an art, and virtue a tedious convention. He fascinates Dorian not by corrupting him but by giving eloquence to his instincts. He articulates what others suppress. Under his influence, Dorian learns to live not for goodness but for grace, not for conscience but for effect.

Wilde fills their dialogues with exquisite balance. The lines hover between irony and elegance, philosophy and provocation. It is not mere conversation; it is fencing in silk gloves. Behind the laughter, one senses a growing chill. The world of Wilde is beautiful, but it is a beauty that has begun to suspect itself.

The Artist and the Idol

Basil Hallward, the painter, stands apart from the others. He loves Dorian not as an object but as an ideal. His art and his affection are inseparable. In painting Dorian, he paints his devotion, and in doing so, seals his doom. Basil’s studio becomes a temple of dangerous worship. When he pleads with Dorian to repent, it is not the plea of a priest but of an artist whose creation has betrayed him.

“You have made me see what art really is.”

Basil represents sincerity in a world that mocks it. He is the moral compass of the novel, but Wilde, ever ironic, ensures that goodness cannot save him. The murder of Basil is not born of rage but of fatigue. Dorian cannot bear the reflection of purity; it disturbs his poise. The act is swift, almost graceful, as if he were erasing a flaw in composition.

Here Wilde achieves his cruelest symmetry. The artist dies by the hand of his art. What he created in beauty destroys him in truth. The brush and the knife, in Wilde’s imagination, are instruments of equal delicacy.

The Portrait as Conscience

The hidden painting is the novel’s beating heart. It is both mirror and punishment, both evidence and echo. Its transformation from loveliness to horror is the spiritual diary of Dorian’s life. It sees what the eyes refuse to acknowledge.

Each sin it absorbs becomes a visible scar upon the canvas. When Dorian looks at it, he confronts not fear but fascination. His guilt becomes aesthetic. He studies his own corruption with the detached curiosity of a critic.

“The portrait would bear the burden of his shame.”

This is Wilde’s greatest irony. The man who worships beauty becomes obsessed with ugliness. In fleeing morality, Dorian merely changes its shape. His pursuit of pleasure leads him not to liberation but to imprisonment within his own vanity. The portrait, silent and loyal, keeps his secret until the secret consumes him.

Wilde’s Paradox of Art and Morality

Wilde’s triumph lies in his refusal to preach. He does not condemn Dorian; he admires the symmetry of his ruin. The Picture of Dorian Gray is not a sermon but a dance — slow, elegant, and inevitable.

He wrote in an age that adored propriety and punished beauty for being honest. The Victorians, forever anxious to appear virtuous, read Wilde’s novel as if it were a scandal rather than a mirror. When accused of immorality, Wilde replied with perfect calm:

“There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all.”

To Wilde, art was self-contained. It owed nothing to ethics. Yet in writing Dorian’s story, he betrayed his own theory, for the novel trembles with moral undercurrents. Beauty cannot protect itself from truth, nor can art escape the human pulse that creates it.

The Fall of the Beautiful

When Dorian finally stabs the painting, it is not repentance but rebellion. He wishes to destroy evidence, not erase sin. But the moment the knife touches the canvas, the illusion collapses. The portrait regains its original beauty, and the body before it lies old, withered, and unrecognizable.

“Each man sees his own sin in Dorian Gray.”

The balance is restored. The painting and the man exchange their fates. Wilde ends not with punishment but with proportion. The symmetry of art is satisfied. Beauty, though corrupted, survives; only the pretender perishes.

This ending is neither tragic nor moral. It is aesthetic justice. Dorian dies because the world of Wilde allows no disorder that lacks grace. The knife that kills him is also a brushstroke, restoring harmony to the picture.

Wilde and His Shadow

It is impossible to read the novel without sensing Wilde himself in its pages. His wit is Lord Henry’s, his passion is Basil’s, his charm is Dorian’s, and his doom is shared by all three. The story reads like prophecy. The man who believed that beauty was the highest truth was soon destroyed by society for the very beauty of his difference.

In Dorian’s destruction lies a faint echo of Wilde’s own trial and fall. The portrait that aged for Dorian was, in a sense, the public opinion that aged for Wilde. The world could not forgive what it could not define. The artist who gave sin such elegance was made to pay for the elegance more than the sin.

The Eternal Reflection

The Picture of Dorian Gray endures because it refuses to settle into lesson or legend. It remains poised between temptation and truth, its surface radiant, its depths uneasy. It teaches without preaching, condemns without anger, and seduces without mercy.

Beauty, Wilde reminds us, is both promise and peril. To worship it is divine folly; to defy it is dull wisdom. Between the two lies the whole tragedy of being human. Dorian sought eternity in the stillness of art and found decay in the motion of life.

The reader closes the book, uncertain whether to admire or repent. That hesitation is the mark of great art. It leaves one questioning not the characters but oneself. Wilde did not write a moral fable; he wrote a mirror. It reflects only what one brings to it.

“Behind every exquisite thing that existed, there was something tragic.”

ABS closes the scroll.

The candle burns low. The portrait gleams in silence.

Some faces are too fair for time, some sins too elegant for forgiveness,

and art — always — outlives the heart that made it.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance