A Satirical Journey Through Ancient Pride and Modern Vanity

What ABS Believes

Satire walks into a room quietly but exposes everything loudly.

Jonathan Swift did not approach intellectual quarrels the way timid scholars did. He walked straight toward them with the confidence of a man who knew he was about to expose everyone. When he watched the swelling argument between the ancient writers and the modern writers, he realised that this was not scholarship in motion. This was ego dressed as learning.

During his years with Sir William Temple, Swift witnessed Temple defend the ancients with the seriousness of a king defending a crown. Temple praised Homer and Virgil as unmatched geniuses. The modern scholars responded not with calm reasoning but with offended outrage. They declared the ancients obsolete. They attacked Temple personally. They waved their newly printed books like victory flags.

Swift observed them and instantly understood the truth he would later turn into satire. The quarrel was not about literature. It was about human vanity pretending to be wisdom. It was about scholars protecting pride rather than truth. The louder the voices became, the clearer the comedy grew.

A thought rose in Swift’s mind. It was sharp. It was amused. It was accurate.

“When pride speaks louder than wisdom, knowledge turns into noise.”

The idea delighted him. And from that delight came the spark that would ignite the entire narrative.

“If the scholars refuse to stop fighting for the books, the books shall fight for themselves.”

Cue: The Battle of the Books.

With that single decision, Swift turned the great Royal Library at Saint James into a living stage. The shelves stood like rival kingdoms. The ancient manuscripts lay in dignified silence, carrying centuries of endurance in their stillness. The modern books gleamed with bright ink and loud confidence, full of the excitement that comes from youth rather than depth.

Swift let the ancient pages whisper with gravity. He let the modern pages rustle with ambition. He let Homer rise like a warrior who had defeated time. He let Virgil polish his calm authority. He let Aristotle open with the certainty of a mind that shaped centuries. On the opposite shelves he let the moderns murmur about progress and novelty as if the world had only begun to think in their generation.

Swift captured this contrast in a line that stands as the spirit of the entire debate:

“The light of ancient learning grows steady with time. The glare of modern vanity burns bright and fades quickly.”

With that, the library ceased to be a quiet hall and became a charged arena. Scrolls stirred like seasoned soldiers ready to stand again. Modern volumes trembled with the brave enthusiasm of those who have not yet been tested. The air thickened. The books awakened. Ideas rose like the first movement of an orchestra tuning for battle.

Swift’s introduction is a reminder that no era owns wisdom, that every age is tempted by pride, and that literary quarrels reveal human nature far more than literary truth.

This is where the battle begins.

A library awakening.

A quarrel sharpening.

A satire taking shape.

THE SAINT JAMES LIBRARY AWAKENS

The Royal Library of Saint James was never meant to move. It was designed to sit in silent majesty, breathing dust and authority, intimidating scholars into good behaviour while pretending to care about their opinions. For years it did exactly that. It stood like a grand intellectual cathedral, tall windows spilling light onto endless shelves, ancient scrolls curled in dignified sleep, and modern books glowing with the smug brightness of ink that had barely dried.

But Jonathan Swift had other ideas. When he began imagining the great quarrel between the ancients and the moderns, the library refused to stay still. It stretched. It murmured. It readjusted its shelves the way an old general might roll his shoulders before battle. This was no longer a room for reading. It was about to become a battlefield for vanity.

The ancient manuscripts lay on the right side of the library in a calm golden glow, as if time itself fell respectfully silent around them. These were books that had survived fires, wars, plagues, critics, bad translations, student annotations, and every aggressive scholar determined to “improve” them. They carried scars in their pages but also majesty. Their silence was not emptiness. It was authority.

On the opposite side stood the modern books. Bright covers. Sharp corners. Pages stiff with ambition. They did not sit quietly. They vibrated with the energy of overconfident newcomers. They whispered to each other about innovation. They celebrated their freshness. They admired themselves in the reflection of polished cabinets. In their minds they were the future. In their hearts they were the revolution. In reality they were loud.

The tension rose the moment the sunlight shifted. Swift described this awakening with the awareness of a man who knew that intellectual battles are never about intellect.

“The light of learning is steady on the ancient side. The glare of novelty is restless on the modern side.”

This was the moment the library began to breathe. A few ancient scrolls stirred. The modern books rustled as if clearing their voices before performing an argument they had not rehearsed properly. The air thickened. Even the dust held its breath.

The first sound came from Homer. Of course it did. His pages fluttered like the wings of a large, irritated eagle who had been disturbed from a dignified nap.

Homer shifted slightly on the shelf and muttered with the irritation of someone who has been wise for too long.

“I have survived empires. I will survive this nonsense.”

Virgil elegantly adjusted his spine, radiating an effortless confidence that suggested he had never lost an argument in his life. Aristotle straightened with a calm that felt like a philosophical shrug. Plato glowed faintly, as if the Forms themselves were whispering encouragement.

They were not angry. They were mildly disappointed. Which is always worse.

On the modern side, the books reacted with gleeful excitement. A newly printed collection of essays trembled dramatically as if preparing to conquer civilisation. A book of experimental criticism tilted itself closer to the window so its glossy cover caught the light. A scientific manual buzzed with impatience, keen to correct someone. Anyone. Preferably everyone.

One bold modern volume finally broke the silence and shouted across the room:

“Make way for progress. The world belongs to the new.”

An ancient scroll cracked open with a sound that felt like thunder politely clearing its throat.

Horace whispered dryly,

“The world belongs to those who understand it. Do sit down.”

This irritated the moderns immediately. They believed that being new automatically meant being right. They believed that freshness of ink equalled freshness of mind. They believed that age was a flaw rather than a foundation. Swift observed this behaviour in the real literary world and showed no mercy. He turned their pride into comedy.

A modern critic’s handbook called out loudly,

“We improve the ancients. They should thank us.”

Aristotle raised a single metaphorical eyebrow. It was magnificent. The modern books felt the weight of that eyebrow like a philosophical verdict.

One of the younger moderns, a slim commentary filled with fashionable theories, puffed up its pages and replied with great confidence,

“Your ideas belong to the past.”

Plato answered softly, which somehow made it worse.

“Truth has no expiry date.”

The moderns huddled together, offended and energised. Their pages fluttered like angry birds. They murmured about outdated traditions, unnecessary reverence, the triumph of modern thinking, and the need to replace the old with the new simply because it felt exciting.

The ancients remained calm. They exchanged no rushed whispers. They showed no panic. They did not shout. They understood something the moderns did not.

Wisdom speaks quietly because it knows it will be heard eventually.

Meanwhile, loudness is forced to shout because it fears it will be forgotten.

Swift’s humour rests on this contrast. He understood that every age believes itself wiser than the last. He understood that pride persuades the modern mind to call itself superior without earning the title. He saw critics inflate their opinions like balloons and float above the understanding they never possessed.

This observation shaped the entire structure of the library. The right side was calm light. The left side was restless shine. The right side was depth. The left side was noise. The right side was continuity. The left side was rebellion without direction.

The Saint James Library, once peaceful, was now a room holding its breath. Shelves tilted as if preparing for alignment. Scrolls rolled themselves more tightly. Modern books stiffened their spines. The tables trembled with the faint vibration of coming conflict. The dust on the upper shelves shimmered like ancient soldiers polishing their armour.

Swift’s vision was brilliant because he did not simply portray a feud. He revealed a pattern that repeats in every generation.

Every time a new idea arrives, it believes it has conquered all ideas that came before.

Every time an old idea endures, it believes it cannot be replaced.

Both sides forget that literature is not a competition. It is a conversation.

And yet, here in the library, the conversation was over. Only rivalry remained.

One more voice rose. A calm, deep, ancient voice.

“Wisdom is not young. Vanity is.”

The modern books bristled. The ancient pages glowed. The sunlight sharpened. The floor tightened beneath them like a stage preparing for the opening act. Swift’s theatre of satire had come to life.

The Saint James Library had awakened. And nothing inside it was ready to behave.

THE ARMIES RISE INSIDE THE LIBRARY

The Saint James Library had awakened, and now it began to organise itself with the seriousness of an empire preparing for war. Books that had never moved in centuries began shifting across their shelves with surprising enthusiasm. The ancient manuscripts rose slowly, not out of laziness, but out of the regal dignity of those who never rush. The modern books leaped upright as if someone had told them the future was offering discounts on glory.

The right side of the library, home of the ancients, glowed with a deep golden stillness. These were the giants of civilisation. Homer, Virgil, Plato, Aristotle, Horace, and other monumental voices arranged themselves with the calm assurance of minds who had shaped centuries. Their pages whispered like silk. Their bindings creaked like old warriors stretching before a familiar battle.

The left side, belonging to the moderns, shimmered with bright colours and louder ambition. They were restless. They were excited. They were absolutely certain they were about to win. A newly printed book of experimental criticism hopped forward with the confidence of someone who has never been defeated only because they have never actually been tested.

Swift steps back here, quietly amused. He knows exactly what he is doing. He let the library wake. Now he lets it divide. The room is becoming two armies, two ideologies, two egos, two delusions.

The ancient side begins to assemble. Homer stands at the front, pages humming with the resonance of epic battles long past. Virgil positions himself with the poise of a poet who can defeat his enemies with elegance alone. Aristotle rises with the gravity of a man who categorised the universe and expects the universe to stay in its categories. Plato glows softly like a lantern of ideas.

They stand in effortless formation. No shouting. No chaos. No frantic movement. Only a quiet, heavy authority that fills the room.

Across the aisle, the modern books attempt the same. They absolutely fail. A biography of a fashionable philosopher trips over a poetry collection that insists on being alphabetised differently. A modern scientific manual tries to take command but is drowned out by a flood of self important essays shouting contradictory theories. A book of modern morals tries to move forward but loses a page in the process, causing instant panic.

One of the moderns finally yells across the room with more enthusiasm than logic.

“We represent the spirit of progress. Stand aside, ancients.”

The ancients respond with silence. The kind of silence that carries centuries of judgement. The moderns hate it instantly.

Homer finally opens a few lines of his epic and says calmly,

“The world has seen your type before.”

This causes an uproar among the moderns. They begin fluttering their pages faster than frightened pigeons. A few books try to form a line but mistakenly face the wrong direction and bump into the books behind them. Chaos spreads. A manual of modern geography sombrely informs the others that it does not know where it is supposed to stand.

Virgil watches this scene with a serene expression that seems to say he expected nothing more and nothing less.

“A battle is not a parade,” he observes, his voice smooth and poetic.

A modern scholar’s handbook tries to respond with cleverness but misquotes itself, which is truly impressive. Aristotle looks genuinely offended that the book managed to misunderstand its own argument.

The moderns decide to compensate with volume. A brightly coloured volume of scientific optimism leaps forward and shouts,

“We are the age of reason. We are the future. We are improvement itself.”

The ancients blink. Slowly. Almost politely. Then Horace, in the soft voice of a poet who has outlived hundreds of loud idiots, replies,

“Improvement is not a crown. It is a duty.”

The moderns recoil. They hate duties. They adore crowns.

A small but extremely confident modern pamphlet, thin as ambition and just as loud, pushes itself toward the front line and declares,

“Age does not make you superior.”

Aristotle finally speaks, and the room changes temperature.

“Age does not make us superior. Excellence does.”

There is a full five seconds of quiet. The modern books are obviously unsure whether to be offended or impressed. A few decide to be both, which results in them turning to the wrong shelf entirely.

The ancient army continues its preparation. Homer lifts his epic like a shield. Virgil sharpens his lines. Plato arranges ideas carefully, as if placing stars in order. Aristotle gathers arguments like arrows. Horace polishes his satire.

But the moderns cannot stop talking. They treat silence as an insult. They treat discipline as repression. They treat age as inconvenience. A modern historical treatise cries out dramatically:

“The ancients are relics. We are the new mind of mankind.”

Plato glows slightly brighter in response. It is not anger. It is pity.

Meanwhile, a modern translator of fashionable French essays jumps forward with tremendous confidence and zero accuracy. He mispronounces half his own title and immediately blames the ancients for distracting him.

This is Swift’s brilliance. He does not mock the moderns because they are modern. He mocks them because they are loud without substance. He mocks them because they confuse activity with achievement. He mocks them because they believe popularity equals progress.

The ancient side remains firm. Their unity is silent strength. Their posture is quiet conviction. Their glow is deep and steady. They do not shout because they do not need to.

The moderns huddle together and begin strategising noisily. It is exactly as productive as you imagine. A book of modern rhetorical tricks tries to motivate others with inspirational nonsense that sounds suspiciously like it was copied from three different sources. A pamphlet on innovation insists they should attack immediately, but another pamphlet argues they should wait because attacking now might ruin their aesthetic.

A dictionary of new terminology attempts to unite them, but fails because half the moderns do not agree on definitions.

Swift narrates all of this without raising his voice. He simply watches the ego of the moderns collide with the patience of the ancients. His satire glows beneath every movement.

And then it happens.

A soft tremor moves through the library. Not a tremor of fear. A tremor of recognition. The armies have formed. The ancients stand ready. The moderns stand restless. The air thickens like a curtain about to rise.

One final voice echoes across the hall, deep and resonant and old.

“Wisdom does not shout. Wisdom endures.”

The moderns shiver at the weight of the line.

The Saint James Library has chosen its two armies.

They are standing face to face.

The battle is coming.

And Swift knows this is only the beginning.

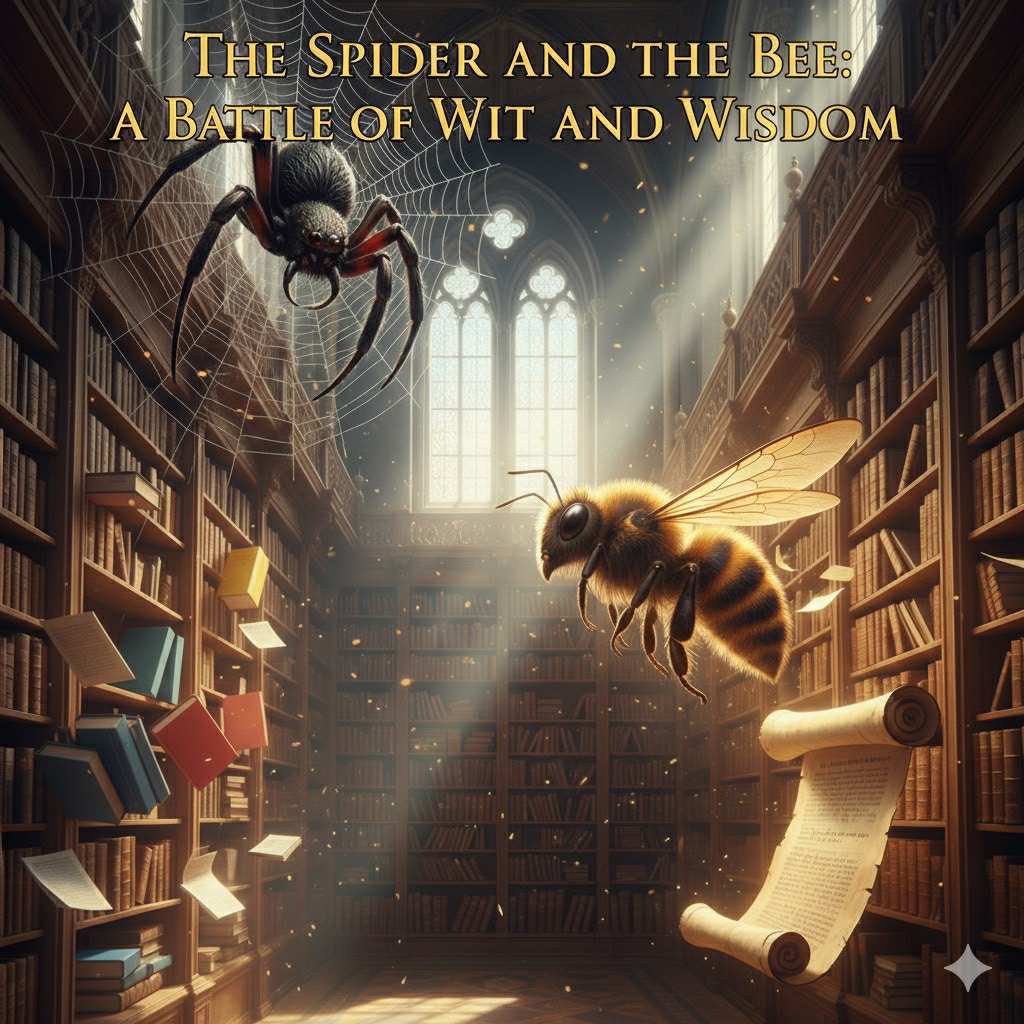

THE SPIDER AND THE BEE ENTER THE BATTLE

The Saint James Library was almost vibrating now. Two armies stood facing each other, ancient dignity glowing on one side, modern ambition trembling on the other. The air was thick enough to slice with a bookmark. It felt like the entire library was holding a collective breath, waiting for someone to blink, cough, sneeze, misquote Aristotle, or lose a page.

And then, just when the tension reached the point where even the dust motes looked nervous, something entirely unexpected happened. From a shadowed corner of the library came a faint but unmistakably arrogant voice. Not a book. Not a scroll. Not a manuscript.

A spider.

It descended slowly from a thread of self importance, swinging gently like a philosopher preparing a ted talk nobody asked for. It paused in mid air as if expecting applause for the dramatic entrance. None came. The ancients ignored it. The moderns considered cheering but forgot to agree on the volume.

The spider finally cleared its throat and announced itself with the confidence of someone who had absolutely no idea how ridiculous it looked.

“Behold the mind of the modern age.”

That was it. No explanation. No context. No humility. Just a declaration of grandeur from an insect that had produced nothing but sticky furniture.

Across the room, a warm golden flutter appeared. A soft hum. A gentle breeze. And from the light emerged a bee. Graceful. Steady. Radiating purpose. It hovered with elegance, as if it had been invited to the conversation but arrived fashionably late to make an entrance.

The bee landed on a scroll with the refined confidence of someone who knows that quality needs no announcement. It looked at the spider. The spider looked back. The books looked at both of them. Swift smiled inside his skull like a man who had just invented the most devastating metaphor of his career.

The spider puffed up its tiny body and began to speak again.

“I am the symbol of modern originality. I spin my own web from my own bowels. I create everything myself. I borrow nothing.”

There was a long pause. Even the modern books shifted uncomfortably. The spider had just bragged about producing its content from inside its digestive system. Not a great look for the modern army.

The bee finally responded. Calm. Polite. Deadly.

“You produce what you consume. I produce what I gather.”

This was not simply a reply. It was a cosmic slap.

The spider twitched. The modern books gasped. The scrolls glowed. The entire library leaned in to watch.

The spider tried to recover. It flung one leg dramatically at the empty space between them.

“Your work is not original. You steal from every flower.”

The bee almost smiled. If bees could arch eyebrows, this one would have reached the ceiling.

“I collect. I combine. I transform. That is the purpose of art.”

A slow ripple of admiration moved through the ancient side. Plato nodded approvingly. Aristotle whispered something about synthesis. Homer muttered something that sounded suspiciously like applause.

The spider, still offended, began to pace along its thread, which did not help its dignity. It pointed one leg at the bee as if accusing it of plagiarism.

“You are nothing but a recycler.”

The bee fluttered its wings once, golden dust scattering like tiny stars.

“And you are nothing but a producer of cobwebs. Fine decoration. Absolutely no nourishment.”

The modern books flinched. The spider deflated. The ancient scrolls glowed brighter. Swift was enjoying himself so much at this point that you could almost hear his quill laughing.

To make matters worse for the spider, the bee continued with devastating calm.

“Your webs trap. My honey feeds.”

The spider had no comeback. The modern army looked at it with the same expression students have when their teacher asks them to explain a poem they did not read. Awkward. Guilty. Slightly betrayed.

But Swift is never satisfied with one metaphor when he can produce an entire philosophy. He takes the scene further. He gives each insect more symbolism than some writers give their entire novels.

The spider becomes the emblem of modern arrogance. It produces everything from itself. It refuses to learn. It refuses to gather. It refuses to acknowledge the world. It spins webs in corners and mistakes confinement for creativity.

The bee becomes the symbol of ancient wisdom. It gathers from many sources. It transforms beauty into nourishment. It creates something new from what already exists. It works with the world rather than against it.

This is the moment Swift reveals his real point. It is not just ancient versus modern. It is not just old versus new. It is creation versus imitation, depth versus decoration, substance versus noise.

The bee flies in a small graceful circle and settles again, completely unbothered. It has made its point. It knows it has won. It knows even the dust motes agree.

The spider tries to climb higher on its thread, perhaps hoping the altitude will restore its dignity.

“I create from my own body. That is true originality.”

The bee delivers the finishing blow.

“Then your originality is your prison.”

Silence.

A glorious silence.

A silence so complete even the youngest modern book decided to stop rustling its pages.

Swift uses this silence like a painter uses empty space. It frames the message. It sharpens the satire. It allows the reader to see exactly how foolish self important originality looks when compared to thoughtful creation.

The ancient army slowly rises a little taller. They do not cheer. They do not clap. They behave like people who expect respect because they earned it.

The modern army… does what the modern army always does. They whisper hurriedly among themselves and decide the conversation was biased.

One modern book mutters resentfully,

“The bee is old fashioned.”

Horace replies from the ancient side,

“And yet, it still works.”

It is the most polite humiliation in the history of libraries.

The spider retreats to its corner, spinning its web with renewed but wounded enthusiasm. The bee returns to the golden side, humming softly as if summarising its victory in a private melody.

And now the library is no longer just awake. It is alert. It is alive. It is judging. It is choosing sides. The armies feel it. The dust feels it. The shelves feel it. The sunlight itself looks ready to watch the battle like front row entertainment.

The spider and the bee have spoken.

The message is clear.

The war is beginning.

And the Saint James Library trembles in anticipation.

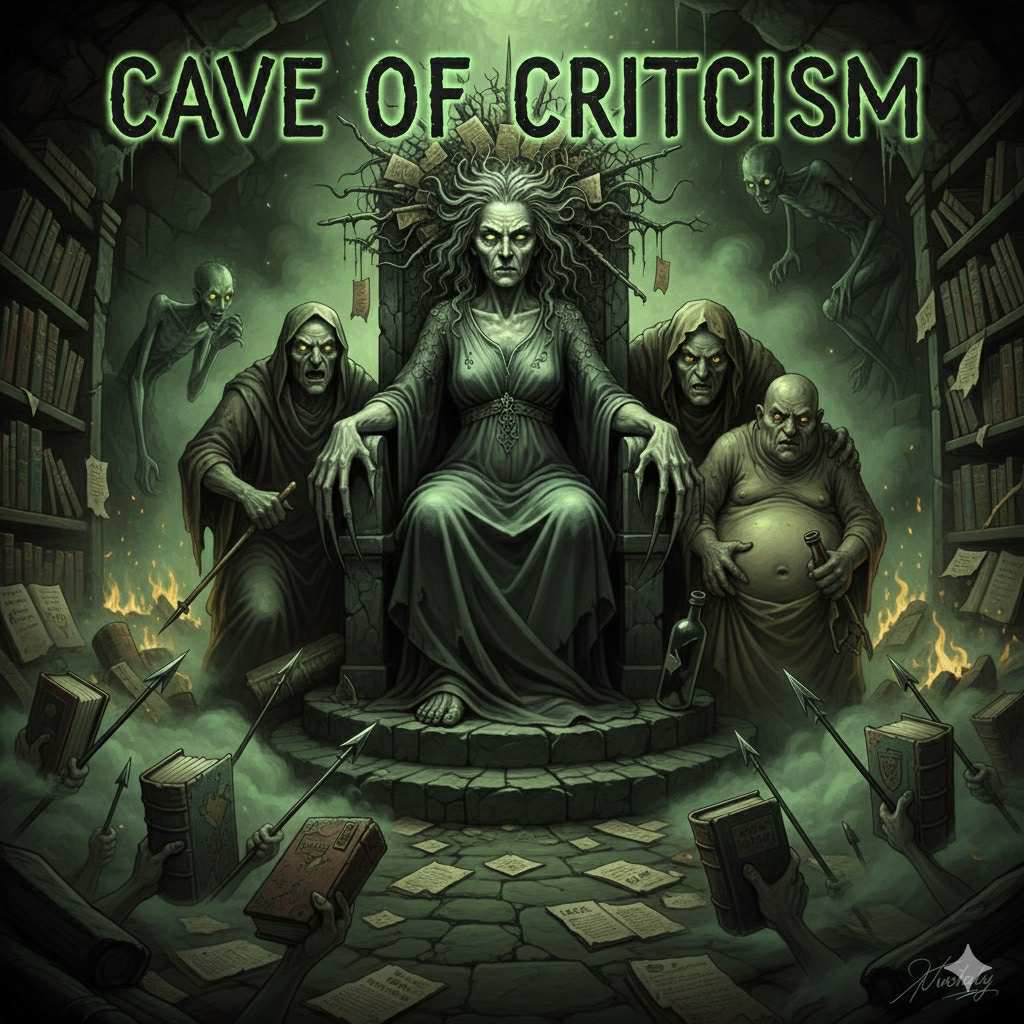

THE CAVE OF CRITICISM AND THE GODDESS WHO LOVES CHAOS

The Saint James Library had already awakened, divided itself, formed armies, and survived a duel between a philosopher bee and a pretentious spider. By this point even the sunlight had stopped being neutral. It tilted toward the ancients in admiration and squinted suspiciously at the moderns, as if reconsidering whether light should be wasted on fragile confidence.

But Swift was not finished. He had one more layer of satire to unfold. A darker one. A funnier one. An absolutely merciless one. Because every war needs reinforcements, and the moderns, being modern, had only one place left to seek help.

The Cave of Criticism.

A location so gloomy, so dramatic, so perfectly suited for mischief that even the dust inside it probably held grudges. It was not inside the library. It was beneath it. A collapsed underworld of opinions, anxieties, insecurities, bitterness, and people whose job was to judge books they barely read.

Swift leads us down into the cave like a tour guide who has been paid extra to enjoy the suffering he is about to reveal.

The cave is enormous. It is ancient. It is unpleasant in the way neglected comment sections are unpleasant. And in the very centre of this cavern sits the ruler of the entire underworld of judgment.

The Goddess of Criticism.

Swift describes her with the tenderness of a man sharpening a knife.

She is old.

She is hunched.

She is wrinkled with resentment.

She is nourished by poisonous vapours that rise from the floor like the ghosts of murdered drafts.

Her hair is tangled with decades of negative opinions.

Her fingernails are long enough to tear reputations.

Her voice is a blend of echo, complaint, and chronic dissatisfaction.

She is the mother of all critics.

And by critics Swift means people who cannot create but can destroy with impressive enthusiasm.

Swift lets the Goddess of Criticism breathe once, and the entire cave trembles.

From the shadows crawl her loyal children and assistants. They are not beautiful. They are not inspiring. They are not ideal company for anyone who values joy or clarity.

Here they come.

Crapula. The spirit of bloated ignorance who consumes texts without digesting meaning.

Zoeilus. The incarnation of jealous criticism, famous historically for attacking Homer because his own poetry was bad.

Momi. The god of fault finding who travels with a personal cloud of negativity.

Envy. The queen of corrosive bitterness. She drinks resentment for breakfast.

These creatures crawl around the Goddess like ambitious assistants waiting to bring down the productivity of the entire office. Their job is simple. They sharpen criticism into weapons sharp enough to pierce even the most respectable texts.

Swift pauses to give us a perfect line:

“For criticism thrives best in the dark, where no reason can interrupt it.”

The moderns look at this cave and feel hope for the first time. Which tells you everything about them.

They gather at the cave entrance like tourists waiting to enter a haunted attraction. Their pages flap nervously. Their colours dim slightly. Their pride flickers. But they march in, believing the Goddess will give them the power they need to defeat the ancients.

The ancients do not follow. They do not need criticism. They have clarity. They have depth. They have survived centuries without the assistance of bitter shadows.

The moderns enter the cave as one messy troop. The moment they cross the threshold, the air grows thick with negativity. The Goddess rises from her seat with a creak so dramatic it should have been accompanied by thunder.

She looks at the moderns the way a lecturer looks at a student who announces they did not read the book but are prepared to share strong opinions about it.

The moderns bow with excitement. One of them, a new treatise on social theory with more style than content, steps forward and cries out:

“Great Goddess, bless us with the weapons of criticism so we may defeat the ancients.”

The cave echoes.

A few stalactites fall.

Even darkness rolls its eyes.

The Goddess leans forward. She smells of old books that were never opened. Her breath is the scent of decaying confidence.

She speaks with a voice that crawls into the spine of every modern book.

“I offer no wisdom. Only weapons. Take them. Use them. Wound them.”

She reaches into a chest made of shattered reputations and hands out tools one by one.

Poisoned arrows of envy.

Daggers made from misquotation.

Shields built from selective reading.

Spears carved from arrogance.

Stones of insult.

And the heaviest weapon of all:

Arguments stripped of evidence but wrapped in loudness.

The moderns gasp in delight. They treat these tools like divine gifts. They do not question the ethics. They do not question the purpose. They do not question anything. They simply clutch their new weapons and feel invincible.

A modern critic’s handbook grabs a handful of poisoned darts and whispers to itself with delight.

“Now I can destroy even the books I never understood.”

The Goddess nods approvingly. She loves confidence without comprehension.

Envy slithers forward and drapes itself over the moderns, coating them in a thin layer of bitterness that will fuel their attacks. Momi dances around them, whispering faults into their ears. Crapula burps unpleasantly in approval.

The ancient army, watching from the library above, sighs collectively. They recognise this pattern. They have survived it before. They have weathered centuries of criticism handed out by people who wanted fame without effort.

Swift uses this moment to give another perfect pull quote.

“For modern critics ever strike hardest at what they understand least.”

The moderns march out of the cave with their new arsenal. They are louder. They are prouder. They are more misinformed than ever. They are absolutely convinced they have discovered the secret to victory.

The Goddess of Criticism watches them leave with a smile that should worry everyone.

Her cave grows darker.

Her children retreat into the shadows.

The air settles again into poisonous calm.

Above, the Saint James Library trembles.

The ancient army glows.

The modern army rattles.

And the war, now fully armed, steps closer.

The cave has given the moderns weapons.

But it has also given the ancients something far more valuable.

A reason to win.

THE FINAL BATTLE AND THE FALL OF WOTTON AND BENTLEY

The Saint James Library had endured awakenings, arguments, insect philosophy lessons, and a generous distribution of toxic enthusiasm from the Cave of Criticism. Now it stood on the edge of something larger. Something louder. Something only Jonathan Swift could design.

The final battle.

If the earlier moments were sparks, this was thunder. If the earlier quarrels were whispers, this was an opera. The spectators were not humans but shelves. The air did not carry dust but tension. And the combatants were not warriors but books, manuscripts, ideas, and egos that refused to behave.

The ancient army stood ready. Their ranks glowed with calm golden light. Homer positioned himself at the front, pages steady and unshaken. Virgil raised his lines with poetic elegance. Aristotle held arguments like a quiver of arrows. Plato shimmered with quiet certainty. They carried no unnecessary pride. Only the memory of endurance.

The modern army trembled with noisy excitement. Some shook with confidence. Some trembled with fear. Some shook simply because they had too many loose pages. They armed themselves with the weapons the Goddess of Criticism had provided. Poisoned quills. Shields made of shredded logic. Spears whittled from loud opinions. Arrows of misquotation. Their arsenal was shiny but unstable.

The room brightened. A single beam of sunlight stretched across the library floor like a divine referee. It did not promise fairness. It promised visibility.

The first blow came from a modern book that wanted to impress the ancients with boldness. It hurled a poisoned arrow at Aristotle. The arrow missed Aristotle entirely and stabbed a book of geography, which immediately forgot where it was. A tragic but predictable outcome.

The ancients did not laugh. They were too dignified to laugh. But the floorboards definitely snickered.

Swift directs the next movement with perfect theatrical timing. Homer steps forward, his epic glowing like the dawn of a civilisation. He lifts his metaphorical spear. The moderns panic. Some drop their weapons. Some drop their arguments. A few drop their indexes. A dictionary faints dramatically.

Homer releases the spear.

It moves through the air with the authority of a writer who has survived thousands of years of admiration and will survive thousands more. The spear flies with mathematical precision. It does not waver. It does not falter. It does not forgive.

The modern army watches in horror as the spear heads straight toward two of their most confident champions.

Wotton and Bentley.

The two scholars had been standing shoulder to shoulder, armed with arrogance, armed with criticism, armed with the unwavering belief that they had improved every ancient text they had ever touched. This belief was only slightly less accurate than believing clouds are made of cheese.

The spear strikes.

It pierces Wotton directly. It passes through him with poetic justice. It continues on its unstoppable path. It enters Bentley as well. It binds them both together in a single, irresistible, absolutely humiliating moment.

The library gasps.

The ancients glow.

The moderns wobble.

The spear remains lodged in both scholars as if declaring to the world that arrogance is most dangerous when compounded.

Swift gives us this moment with clean, merciless precision. Two voices silenced by one line. Two critics defeated by one truth. Two egos collapsed by one epic.

A hush falls across the library. Even the Goddess of Criticism, watching from her cave below, pauses her breathing. The moment has weight. The moment has meaning. The moment has humour that is both sharp and polite.

Wotton and Bentley do not collapse immediately. They stand frozen, attached by the spear, like a living sculpture of scholarly overconfidence. The modern books stare in disbelief. The ancient books watch with quiet satisfaction.

The library, which has been a silent audience for centuries, feels something close to poetic catharsis.

Swift allows one more dramatic flourish. As the light intensifies, the wounded scholars begin to rise. Not by their own power. Not by their own brilliance. By divine rearrangement.

Their books and arguments dissolve into a kind of luminous ink. Their pride dissolves into vapour. Their forms ascend upward like small, confused constellations. They float higher, bound together, until they disappear into the golden light near the ceiling.

It is Swift’s way of closing the argument. They do not triumph. They do not crash. They transcend, not as heroes, but as reminders. They become a symbol of the limitations of modern scholarship when it refuses humility.

Swift captures this moment with another perfect pull quote.

“For those who wound wisdom often ascend only to be forgotten in brighter light.”

The battle slows.

The noise fades.

The modern army weakens.

The ancient army steps forward with steady confidence.

A few modern books continue to fight, but halfheartedly. One throws an insult and immediately apologises. Another swings a quill and hits itself. A book of modern philosophy tries to argue its way out but collapses after contradicting its own introduction.

By now the result is clear. The ancients have not lost a single line. The moderns have lost half their arguments. The library settles back into its grand stillness, the kind of stillness that feels like a verdict.

One last line rises from the ancient side. It comes from Virgil, calm as always.

“Time tests all things. Only the true endure.”

The modern army bows its bright, trembling covers. The Goddess of Criticism retreats into her cave and practices frowning in the dark. The ancient manuscripts return to their shelves with serene dignity. The modern books return to their places as well, slightly humbled, slightly quieter, slightly improved by defeat.

The Saint James Library exhales.

The dust settles.

The sunlight softens.

The battle has ended.

Swift does not choose a winner. He reveals one.

The ancient army stands because its foundation is deep.

The modern army faltered because its ambition was shallow.

And as the library returns to silence, one truth remains etched in the air.

“Wisdom outlives pride.”

The war is over.

The laughter remains.

And Swift closes his satire the way only Swift can

by proving that the greatest battles are not fought with swords

but with ideas.

And that is where we leave Swift’s glorious chaos.

Books bruised. Scholars confused. Egos permanently dented.

The ancients walk out like seasoned champions.

The moderns limp out like contestants who never read the rules.

If this battle taught us anything, it is this

the only thing louder than pride is the silence that follows its defeat.

Scroll closed. Curtain dropped. Vanity dismissed.

Abha Bhardwaj Sharma is a Professor of English Literature with over 25 years of teaching experience. She is the founder of Miracle English Language and Literature Institute and the author of more than 50 books on literature, language, and self-development. Through The Literary Scholar, she shares insightful, witty, and deeply reflective explorations of world literature.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance

wonderful reading