(from the series: Literary Theory Explained)

From The Professor's Desk

What if stories didn’t mean what they seemed to mean?

What if literature wasn’t a mirror of reality or a confession of the author’s soul—but a kind of language machine, structured by rules we don’t even realize we’re following? Welcome to the sharp, angular, and brilliantly unnerving world of Structuralism in Literature—a theory that taught us to read not with our hearts, but with a blueprint in hand.

Structuralism in Literature marks one of the most foundational shifts in critical thinking. It moved us away from intuition and impressionism, and toward systems, structures, patterns, and codes. It made us ask: What lies beneath the plot? What framework shapes a myth, a novel, a detective story? And most importantly, can literature be a science of signs? Without this theory, many others—Post-Structuralism, Deconstruction, even Reader Response—would not have a skeleton to rebel against.

A Note from ABS, The Literary Professor

We begin here, with Structuralism in Literature, not because it was the first theory ever imagined—but because it changed the rules of the game.

Before Saussure, we thought language simply carried meaning.

After Saussure, we realized language was constructing meaning—brick by arbitrary brick.

Every theory that follows will either build on, resist, or unravel the logic laid down here. This isn’t just the beginning of our theory scrolls—it’s the architecture of theory itself.

Let’s decode it together.

Before Structuralism – When Meaning Seemed Obvious

H2: Reading Before Structuralism in Literature

There was a time—not too long ago—when reading a book felt like a conversation between the reader and the author. Literature, in that world, was a transparent vessel. A poem evoked emotion, a novel explored morality, and the critic’s job was to pull back the curtain and admire the craft, perhaps explain a symbol or two. The meaning of a text was assumed to be discoverable, singular, and—most dangerously—obvious.

In this pre-theoretical landscape, interpretation meant reconstructing what the author had intended. The reader was a respectful guest; the author, the sovereign of the text. Biographical readings, historical contexts, and emotional intuition shaped most classroom discussions and literary critiques. To know what a book meant was to understand who wrote it and why.

Literary Theory, as we now understand it, didn’t exist in any formal way. There was “criticism”—appreciation, analysis, occasionally correction. But there wasn’t yet a sense that literature operated within systems of meaning-making. No one was yet asking: What if language itself is arbitrary? What if narrative structures are cultural templates? What if the text doesn’t just say something—but says it within a larger code?

That question would arrive, quietly but irrevocably, in the form of Structuralism in Literature.

When Texts Were Treated Like Truth

Before Structuralism in Literature revolutionized the scene, texts were largely read as either moral guides, emotional mirrors, or social documents. A Shakespeare play was a reflection of human psychology. A Dickens novel was a window into industrial England. A Wordsworth poem was Nature’s whisper.

This isn’t to say those readings were wrong—but they were unexamined. They took for granted that the relationship between language and meaning was natural, stable, and direct.

“The meaning is clear,” readers would say. But structuralism taught us to ask: Clear to whom? And according to what code?

In this older critical tradition, we did not question the skeleton—we just admired the skin. The form of a tragedy, the shape of a sonnet, the conventions of a novel—all these were seen as containers, not constructs.

But as the 20th century progressed, particularly after World War II, intellectuals began to realize that what we saw as “literature” was governed by invisible rules—rules as structured as grammar, as coded as mathematics, and as unconscious as myth.

Why Structuralism in Literature Was a Shock

When Structuralism in Literature first entered the conversation, it didn’t just offer a new method of reading. It challenged the very idea of meaning. It asked:

Is the story important—or the structure beneath it?

Is the author in control—or just using inherited codes?

Is meaning in the content—or in the pattern?

To a generation raised on authors as geniuses and texts as sacred, this was nothing short of heresy.

But it was also electrifying. Structuralism offered something that earlier literary criticism lacked: a system. A logic. A method that could be taught, applied, repeated. Literature became a science of stories, not just an art of them.

The Theoretical Gap That Structuralism Filled

It’s important to understand that Structuralism in Literature didn’t arise in a vacuum. It emerged at a time when Western thought was grappling with deep uncertainties. After two world wars, after Freud’s unearthing of the unconscious, after Einstein’s disruption of physical certainty, nothing—not even language—felt stable anymore.

Structuralism answered that instability not with chaos, but with structure. It suggested that beneath the randomness of expression, there were patterns. Predictable, readable, even universal ones.

Critics and theorists who adopted Structuralism didn’t throw away beauty, symbolism, or emotional response—but they placed them within a grid. The poem was no longer a private sigh—it was a cultural code. The novel wasn’t just a story—it was a structure.

A Glimpse at the Turning Point

Imagine a student in 1950s Paris, reading a Greek myth—not for its moral, not for its emotion, but for the structure beneath it.

He notices the same oppositions again and again: light/dark, male/female, wild/civilized, order/chaos. He begins to believe that the myth isn’t a message—it’s a map. A map of how human beings organize the world into binaries.

That student is the product of the structuralist revolution.

And you, dear reader, are about to become one.

Structuralism in Literature – A Theory That Makes Theory Possible

In literary theory, Structuralism is the deep foundation upon which many modern schools of thought rest. It doesn’t just influence other theories—it makes them thinkable. Deconstruction reacts to it. Reader-response shifts away from it. Post-Structuralism breaks it apart. But without Structuralism, none of them would know what they’re dismantling.

“Without structure,” Saussure might have said, “there is only noise.”

And so, to understand anything that follows in this series, we begin with Structuralism in Literature—not because it has the final word, but because it was the first to ask the right questions.

Language and the Turn of the Century

The Shift from What Words Say to How Words Work

By the dawn of the 20th century, it was clear that language wasn’t behaving itself. Words didn’t always mean what they were supposed to. Cultures clashed over translation. Political propaganda twisted meaning. Poets bent syntax. And scientists, philosophers, and revolutionaries began to notice: language was more slippery than solid.

Into this confusion stepped Ferdinand de Saussure, a Swiss linguist whose quiet lectures would later detonate across the humanities. He didn’t set out to change literature. He simply wanted to understand how language worked—not historically, not etymologically, but structurally.

His idea was disarmingly simple: what if language was a system of differences, not a list of labels?

Saussure’s System – Signifier and Signified

Saussure’s theory proposed that every word is made of two parts:

The signifier: the actual sound or visual form of the word (like the letters “C-A-T”)

The signified: the concept the word represents (the idea of a cat)

But here’s the twist—this connection between the signifier and the signified is completely arbitrary. There’s nothing about the sound “cat” that naturally connects it to a furry animal. We just agree to it.

Language, according to Saussure, is not a mirror of reality—it’s a code we’ve all learned. And the meaning of each word depends not on some fixed truth, but on its difference from other words.

“Cat” means what it does because it’s not “bat” or “cap” or “dog.”

In other words, meaning is relational. Words work like chess pieces: their function only makes sense within the whole system.

Why This Matters to Literature

For literary thinkers, this was a revelation. If language itself was unstable and based on systems of contrast, then the foundation of literature was not meaning—but structure.

Stories, too, could be seen this way. A hero only makes sense in contrast to a villain. A tragedy only moves us because it resists the expected comic resolution. Themes, symbols, genres—all operate as systems of difference.

Critics and theorists began to realize: to understand a story, you must study the underlying language logic—not just the characters and plot.

Suddenly, narrative became a code, not just a journey.

The Moment Literature Became Linguistic

It didn’t take long for Saussure’s lectures—posthumously published as Course in General Linguistics—to be devoured by thinkers beyond linguistics. Anthropologists, psychoanalysts, and literary critics seized on his structural model as a universal theory of meaning.

If language is a system of signs, then literature is a system of signs in motion.

This was the turning point when literary analysis shifted from themes to forms, from meaning to mechanism. Stories became puzzles. Myths became maps. Novels became layered blueprints of difference and design.

And the humble reader became a kind of linguistic archaeologist, digging through layers of oppositions to find the system beneath.

Structuralism Begins to Rise

From the ashes of certainty rose a generation of thinkers who would apply Saussure’s insights to everything from fashion to folklore.

One of them was Claude Lévi-Strauss, who would use this approach to re-read tribal myths as patterned, logical, even mathematical texts.

Another was Roland Barthes, who would transform even wrestling matches and advertisements into cultural codes.

But before we get to them, we must acknowledge what Saussure truly gave us: not a theory of literature, but a theory of meaning.

And that, as it turns out, was far more dangerous.

Structuralism in Literature: When Form Became the Function

Something radical happened when linguistics tiptoed into the world of literary criticism. Literature, once cherished for its emotional pulse and imaginative force, was suddenly examined under a microscope of systems, patterns, and forms. Critics no longer asked what a novel meant, but how it meant—what hidden skeletons held its structure upright.

Thus began the era of Structuralism in Literature, a movement that treated literature not as personal expression or historical artifact, but as a system governed by rules, oppositions, and universal patterns. In this framework, a novel was less a story and more a sequence—a coded structure built from recurring elements that made stories intelligible across time and culture.

Structures Beneath the Story

Structuralism began as a linguistic theory, but its journey into literature was inevitable. Ferdinand de Saussure’s revolutionary insight—that meaning in language arises from differences, not intrinsic properties—offered critics a new way to see literature. If language is a system of signs that only make sense through contrast, could literature be built the same way?

The answer Structuralists gave was a resounding yes.

Stories, they argued, do not emerge from inspiration or emotion. They emerge from structures—systems of oppositions, narrative functions, and culturally embedded codes. Literature became the playground of binary forces: life/death, hero/villain, natural/civilized, order/chaos. These opposites did not simply decorate a story; they defined it.

Claude Lévi-Strauss and the Mythic Blueprint

While linguists provided the tools, it was anthropology that pointed literature in a structuralist direction. Claude Lévi-Strauss, studying myths across cultures, discovered that tribal narratives followed deep, often universal structures. Whether in South America or Scandinavia, myths replayed similar tensions: nature against culture, male against female, life against death.

Lévi-Strauss treated myths as systems—not for their content, but for their configuration. By aligning versions of the same myth, he revealed that they all performed the same structural work. This wasn’t storytelling. It was architecture.

Literature scholars soon saw parallels: if ancient myths could be studied as symbolic systems, then why not Shakespeare? Why not Tolstoy? Why not fairy tales or detective novels?

Structuralism thus repositioned the literary critic as a kind of cultural cartographer—someone who mapped the internal logic of a text to reveal the blueprint beneath its beauty.

From Emotion to Engineering

Before structuralism, literary criticism was often steeped in mood and meaning—in the grandeur of Hamlet’s hesitation or the sublime beauty of Romantic verse. Structuralism asked readers to pause their feelings and pick up a ruler.

A tragedy wasn’t tragic because it broke your heart. It was tragic because it followed a sequence: a noble figure commits a grave error, experiences a fall, confronts a recognition moment, and is ultimately destroyed.

Literary forms were not merely expressive; they were predictable. A story functioned not as an expression of human uniqueness, but as a product of a system that made narrative repetition not only possible, but inevitable.

The Structuralist Model of Analysis

Reading literature through a structuralist lens meant analyzing its internal mechanisms:

What are the binaries driving the conflict?

What narrative units construct the plot?

What repetitive functions occur across characters or events?

How does the text conform to or deviate from genre templates?

This was not about what the story felt like—but about what structure it followed.

For instance, Vladimir Propp’s study of Russian folktales reduced hundreds of stories into 31 narrative functions—recurring roles and plot developments like “the hero receives a task,” “the villain is revealed,” or “the hero is rewarded.” These functions, in different combinations, structured nearly all folktales across cultures.

It didn’t matter if the hero was a prince or a pauper. What mattered was that the form remained constant.

From Poetry to Pop Culture

One of the lasting contributions of structuralism was its democratization of textual analysis. If literature operated on underlying systems, then everything did. From opera to comic books, from Shakespearean tragedy to shampoo ads—every text could be analyzed for its hidden structures.

High art and low culture were both systems of signs. A soap opera and an epic poem, while different in tone and depth, might follow identical narrative logics. And so, structuralism expanded the scope of criticism—allowing scholars to examine popular forms like thrillers, superhero tales, or even fashion magazines as meaningful texts.

The boundaries between “literature” and “culture” began to dissolve.

Literature as System, Not Soul

Structuralism posed a profound question: Is literature an individual act of genius—or a cultural structure repeating itself through different voices?

This question haunted the movement. Structuralists didn’t claim that meaning was fake—but rather, that it was produced by a system, not by sentiment. They offered a sober kind of magic: the thrill of recognizing patterns, tracing oppositions, and demystifying the strange universality of storytelling across centuries.

The literary text, in this view, was not a confession. It was a machine of meaning—built from signs, structured by culture, and powered by systems that long predate any single writer’s intention.

Legacy: The Blueprint Before the Breakdown

Structuralism’s influence was vast—and ironic. It laid the foundation for some of the most radical literary theories that would follow. From deconstruction to postmodernism, from feminism to postcolonial critique, nearly every movement that rebelled against order began by studying it—structurally.

Its legacy is not a method but a mindset: that beneath the surface of any story lies a system waiting to be revealed.

In a world overflowing with texts, the structuralist critic does not drown. They dive under the waves, charting the invisible current that pulls all stories along. Not to simplify literature—but to show that even the wildest tale is shaped by an architecture of meaning.

And that, perhaps, is structure’s greatest secret: it hides in plain sight.

Claude Lévi-Strauss and Myth as Structure

When most people think of myths, they imagine gods, monsters, ancient quests, or trickster tales whispered around tribal fires. But when Claude Lévi-Strauss, the French anthropologist, looked at myths, he saw something else entirely: not stories, but structures. Not fantasy, but logic. And not chaos—but a deep, cultural grammar silently organizing it all.

In his hands, myths became more than narrative traditions. They became systems of oppositions—coded blueprints of how the human mind orders the world. Just as Saussure saw meaning arising from differences in language, Lévi-Strauss saw meaning emerging from differences in narrative elements.

He wasn’t interested in whether myths were true. He wanted to know how they worked—and why, in radically different cultures, they often followed strikingly similar patterns.

The Mind Behind the Myth

Lévi-Strauss wasn’t a folklorist collecting stories to preserve their beauty. He was a structuralist in pursuit of cognitive patterns.

His big question was simple:

Why do different societies, isolated by geography or history, end up telling the same kinds of stories?

Whether it’s Greek mythology, Amazonian legends, or African folktales, Lévi-Strauss found repeating oppositions:

-

Nature vs. Culture

-

Life vs. Death

-

Man vs. Woman

-

Order vs. Chaos

His theory? The human brain naturally thinks in binary oppositions. And myths—regardless of time or place—are a way for societies to resolve these oppositions symbolically.

“Mythical thought always progresses from the awareness of oppositions toward their resolution,” he wrote.

How He Did It: Breaking Myths into Mythemes

To analyze myths, Lévi-Strauss broke them down into smaller units he called mythemes—the mythological equivalent of phonemes in language.

For example, take a creation myth:

-

A god falls from the sky

-

A trickster animal steals fire

-

A woman is banished from the village

-

The world is flooded, then reborn

Each of these is a mytheme—a unit of story that, when combined with others, generates cultural meaning. But these units don’t carry significance in isolation. Their meaning arises through opposition and combination.

Lévi-Strauss would arrange them in parallel columns, sometimes mapping different myths side by side, to show their underlying grammar—just like linguistic syntax.

It was a form of storytelling algebra. The myth wasn’t a mystery to be solved—it was an equation to be balanced.

Myths as Machines for Thinking

In this structuralist approach, myths weren’t just entertaining tales or moral lessons. They were machines for resolving contradictions—narrative mechanisms to help cultures work through abstract tensions.

Let’s take an example:

Many myths contain a trickster figure—someone who breaks the rules, shifts between animal and human, male and female, wise and foolish. Think of Anansi the spider, Loki the Norse god, or Coyote in Native American stories.

For Lévi-Strauss, the trickster wasn’t a character. It was a conceptual bridge. He linked oppositions that couldn’t otherwise be reconciled.

He existed not to move the plot, but to stabilize the structure.

This kind of structural interpretation reframed myths as cultural mirrors—not showing what a culture believes, but how it thinks.

Why This Matters to Literature

What Lévi-Strauss did for myth, literary critics soon began doing for literature at large.

If a myth could be broken down into oppositional structures and coded patterns, then so could a novel, a drama, a fairy tale.

Instead of analyzing a single character’s arc, you could analyze the system of character roles across many stories.

Instead of interpreting a poem’s theme, you could decode the binary logic beneath its imagery.

This gave rise to the field of narratology, where critics mapped structural patterns across genres, from romance to horror.

Think of how:

-

Romantic comedies always revolve around presence/absence, misunderstanding/clarity

-

Detective fiction toggles between mystery/solution, guilt/innocence, chaos/order

-

Epic narratives follow a hero’s journey from civilization to wilderness and back

These aren’t accidents—they’re structures.

Lévi-Strauss and the Literary World

Though he worked in anthropology, Lévi-Strauss’s impact on literary theory was immediate and vast.

His ideas gave scholars:

-

A reason to compare texts across cultures and time periods

-

A method for analyzing stories without relying on biography or psychology

-

A way to approach literature as a universal system of signs, rather than isolated works of art

He helped shift the focus from individual meaning to universal structure.

Critics who followed this path weren’t just reading texts—they were charting maps of how literature functions on a collective level.

Not All Stories Are Unique

One of the more controversial implications of Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism was the suggestion that originality is a myth.

If all stories follow the same patterns—just reshuffled—then no text is truly new.

Every story becomes a repetition with variation, a fresh arrangement of ancient oppositions.

This idea would later be taken up by post-structuralists like Barthes and Kristeva, who argued that all texts are made from intertexts—borrowed elements from other structures.

But even before them, Lévi-Strauss was hinting:

You don’t write a story—you perform a structure.

Criticism and Limitations

Not everyone was enchanted by this structural approach to myth and story. Some critics found it too abstract, too divorced from actual cultural practice.

Others argued it ignored emotion, erased historical context, and flattened cultural specificity in favor of tidy binaries.

And of course, real readers don’t experience stories as oppositional grids—they experience them as drama, suspense, heartbreak.

But even critics of Lévi-Strauss acknowledge that his methods opened doors to systematic literary theory. He gave us the tools to treat narrative like a language—and that changed how literature was studied.

The Lasting Impact

To this day, students unknowingly perform Lévi-Strauss’s method when they compare:

-

Hero vs. Villain

-

Civilized vs. Wild

-

Law vs. Chaos

It’s in our storybooks, our films, our political rhetoric. It’s everywhere structure operates beneath content.

Claude Lévi-Strauss didn’t just read myths.

He decoded the human imagination.

And literature would never be read the same way again.

Roland Barthes – Reading Culture as Code

By the mid-20th century, the world had begun reading Shakespeare with the same reverence it gave to Homer—but no one was decoding shampoo ads or French steak dinners. That is, until Roland Barthes arrived with his critical scalpel. Where Lévi-Strauss dissected ancient myths, Barthes brought structuralist tools into the heart of modern bourgeois life.

From fashion photography to wrestling matches, from newspaper headlines to tourist postcards—Barthes treated all of it as text, operating through signs and systems. In doing so, he taught the literary world a powerful truth: that structure isn’t just in literature. It’s in culture itself.

Mythologies: The Hidden Systems of Everyday Life

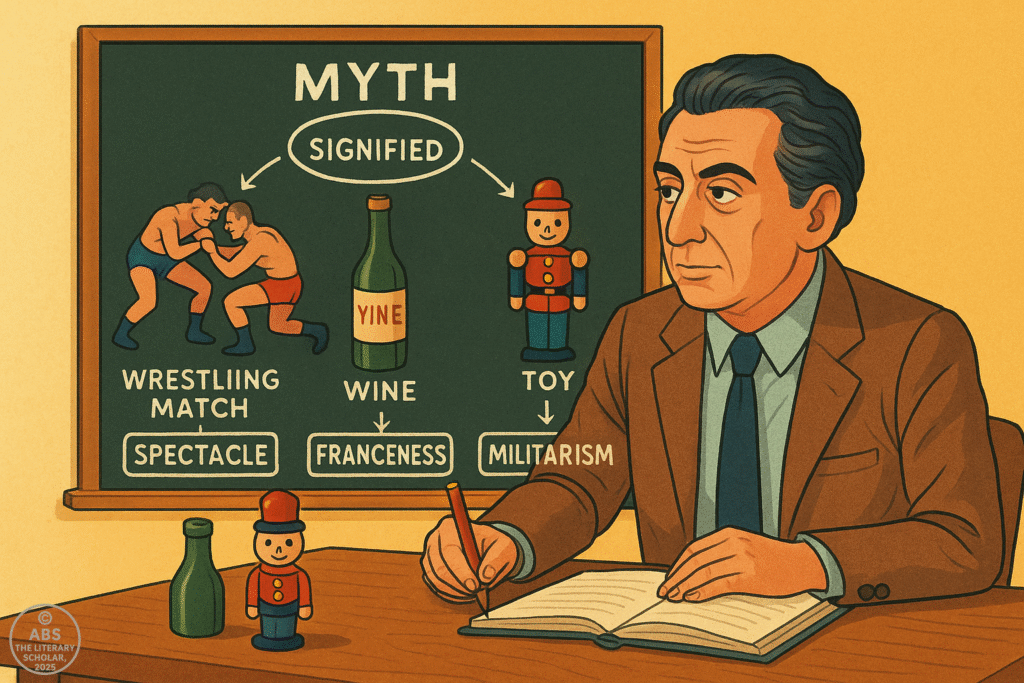

In 1957, Barthes published Mythologies—a slim, brilliant book that would become foundational for cultural criticism. The pieces in it weren’t about novels or plays. They were about ordinary things: soap, toys, wine, film stills, and advertisements.

But Barthes didn’t look at these as consumer goods or aesthetic experiences. He looked at them as signs, and decoded how bourgeois society naturalizes its own ideology through them.

“Myth is a type of speech.”

(Mythologies, 1957)

For Barthes, myth wasn’t fiction. It was a cultural mechanism that made historical constructions appear universal and eternal. A soldier saluting the flag wasn’t just patriotism—it was a myth of national identity. A woman cooking on TV wasn’t domestic charm—it was a myth of gender roles.

And just like linguistic signs, these myths had structures—they functioned through selection, contrast, and repetition.

The Second-Order Sign System

Barthes built his theory of modern myth through what he called a second-order semiological system.

At the first level, a sign consists of:

A signifier (e.g., the image of a rose)

A signified (the flower itself)

At the second level, myth takes that entire sign and gives it a new ideological meaning:

The rose now means romantic love, French elegance, or even mourning, depending on its cultural context.

Barthes showed that meaning is never neutral—it is constructed, often to support dominant values. And just as Saussure had done with language, Barthes revealed how these meanings arise from structure, not essence.

Reading Culture Like Literature

Barthes’s major contribution to Structuralism wasn’t just theory—it was application. He modeled how to read non-literary phenomena structurally, without sentiment, nostalgia, or even moralism.

In one of his most iconic essays, Barthes analyzes professional wrestling—not as sport, but as ritualized narrative.

“What the public wants is not the truth of the fight but the grand spectacle of justice.”

Here, wrestling becomes a coded performance of binary values: good vs. evil, strength vs. cunning, punishment vs. deceit. It is, at its core, a myth with structural logic.

This was a radical expansion of literary theory—it suggested that the world is readable, and everything in it is structured like language.

The Semiotics of the Bourgeois World

Mythologies was also an act of cultural resistance. Barthes wasn’t just mapping meanings—he was exposing how ideology hides in plain sight.

A wine ad could sell “Frenchness.” A children’s toy could encode gender roles. A magazine cover could reinforce whiteness or exoticize Blackness—all without appearing overtly political.

Barthes’s structuralist genius lay in showing that these myths didn’t emerge from intention. They emerged from patterns, from repetition, from the way certain signs are paired and circulated.

In this way, Barthes offered a democratic expansion of literary method. You didn’t need to analyze Hamlet to do serious theory. You could analyze a shampoo bottle—and find the same narrative structures and social codes operating beneath the surface.

Why Barthes Was Still a Structuralist (Then)

Although Barthes would later evolve into more radical theoretical territory, during the Mythologies period, he was still firmly in the structuralist camp.

He believed:

That meaning could be systematized

That signs formed patterns of relations, not isolated symbols

That the analyst’s job was to decode the structure that governs surface meaning

Barthes didn’t question the existence of structure—he believed in it. His critique was aimed at the ideologies embedded within that structure, not the structure itself.

From Literature to Life: The Method Multiplies

Barthes’s cultural criticism taught literary theorists two vital lessons:

Structural analysis can apply to anything

Literature is not the only place where signs generate meaning

This allowed scholars to treat novels, poems, films, ads, comic books—even recipes—as textual systems, composed of signifiers, oppositions, and mythic forms.

It expanded the boundaries of literary studies, made theory practical, and shaped entire disciplines: media studies, cultural studies, and postcolonial theory would all emerge from this impulse.

Legacy and Transition

While Mythologies marked the height of Barthes’s structuralist phase, it also pointed toward his restlessness. His later works would question structure itself—but not yet.

In this phase, he is still the reader as decoder, the theorist as analyst, and the cultural critic who sees myth not as lie, but as system.

“What is characteristic of myth? To transform history into nature.”

(Mythologies, 1957)

Barthes didn’t destroy literature. He democratized interpretation.

And he made us realize: every culture tells stories—but only some know how to read them.

Barthes’s Five Codes (Expanded for Structuralism)

“The goal of structural analysis is not to retell the story but to understand how it is told.” – Roland Barthes

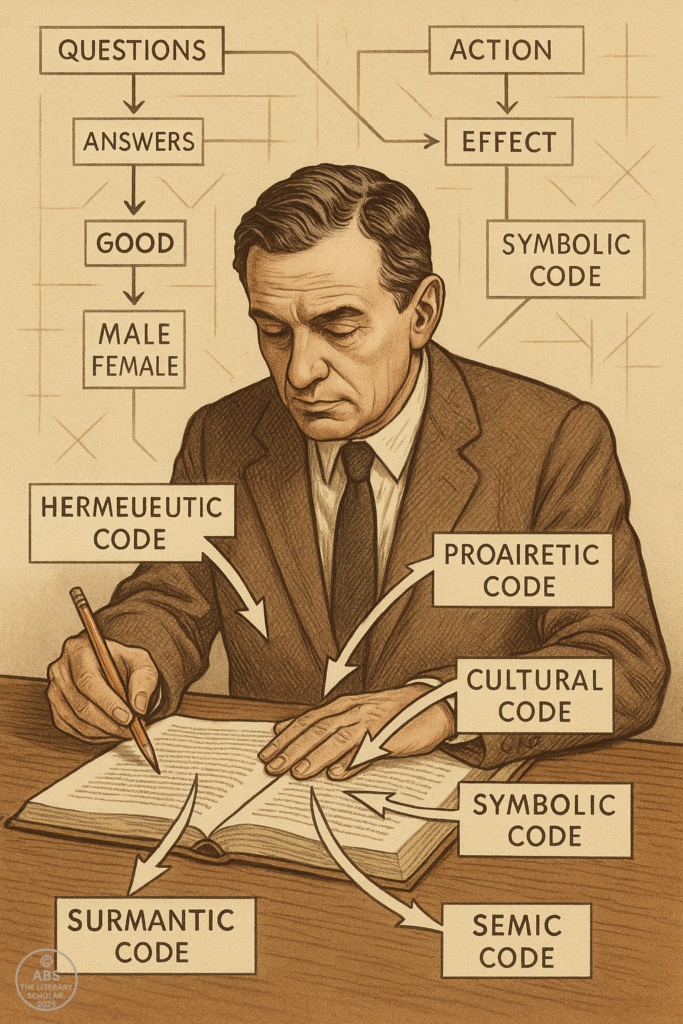

Roland Barthes, in S/Z, proposed that every narrative text operates on five intertwined codes—like invisible strings pulling a marionette. These codes organize meaning, guide interpretation, and structure the reading experience, whether you notice them or not.

Let’s decode these codes.

1. Hermeneutic Code (HER) – The Code of Mystery

*“Who killed Roger Ackroyd?” is never just a question. It’s a trap for the reader.”

This is the code of enigma, suspense, and delayed revelation. It poses a question in the text that’s not immediately answered: a secret, a murder, a missing identity. This is the “detective” within the reader, hungry for closure.

In Hamlet, “Was the ghost real?”

In Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier: “What really happened to the first Mrs. de Winter?”

Every Agatha Christie novel is practically a hermeneutic symphony.

The hermeneutic code is what keeps you reading. The story withholds, teases, and reveals in calculated beats.

2. Proairetic Code (ACT) – The Code of Action

“He opened the door… What happens next?”

This is the code of sequential actions—the stuff of plot. Unlike the hermeneutic code (which asks questions), this one builds tension through physical events and cause-effect chains.

“A scream echoes down the corridor… a shadow moves… someone runs.”

In Macbeth: “The dagger appears… Macbeth walks toward Duncan’s chamber.”

Proairetic code creates momentum. You’re not wondering why something happened—you’re following what happens next.

3. Semic Code (SEM) – The Code of Connotation

“She wore black. Her smile was sharp. Her perfume lingered like regret.”

This code is about character and meaning through suggestion. It uses descriptive signs—clothing, gestures, objects—that signal deeper symbolic or cultural meanings.

A character described with “weathered boots and calloused hands” signals a working-class identity.

Dracula’s cape, castle, and accent cue menace, mystery, and otherness.

The semic code helps the reader assign meaning and identity to characters, settings, moods—without being told explicitly.

4. Symbolic Code (SYM) – The Code of Opposition

“He is day. She is night. He is reason. She is chaos.”

This is the code of binary oppositions, the classic structuralist lens. It operates on duality and contrast, structuring meaning through difference.

Good vs. Evil (Paradise Lost)

Order vs. Chaos (Lord of the Flies)

Masculine vs. Feminine (The Taming of the Shrew, and many Freudian analyses)

Meaning is not in the individual term, but in the opposition: A is only “good” because B is “evil.” These oppositions carry mythic weight.

5. Referential Code (REF) – The Code of Culture

“He carried a cross like a burden.”

This code invokes shared knowledge: history, religion, science, politics, literature. It assumes the reader brings cultural understanding to the text, and uses that to build meaning.

A reference to “Pandora’s box” assumes you know Greek myth.

“Big Brother is watching” only makes sense if you’ve absorbed Orwellian dread.

This code anchors the story in a cultural web. It’s how literature plays on things we already know to say something new.

Barthes believed that no single interpretation could pin down a text. Instead, a text is a weave of these five codes—not a line but a fabric. The reader becomes an active decoder, moving between them.

In this way, Barthes doesn’t kill the author entirely in S/Z—but he does put the reader center stage.

Structuralism Meets Narratology – Todorov and Propp

While Saussure gave us the map and Barthes made it trendy, it was two quietly brilliant minds—Vladimir Propp and Tzvetan Todorov—who did the heavy lifting of applying structuralist thinking to the deep mechanics of narrative.

They weren’t interested in characters or clever sentences. They wanted to know what all stories—fairy tales, detective novels, romances—had in common structurally. And they weren’t afraid to treat literature like a mathematical equation.

In doing so, they helped convert Structuralism from theory to narratology—the science of storytelling itself.

Vladimir Propp: The Functions of the Fairy Tale

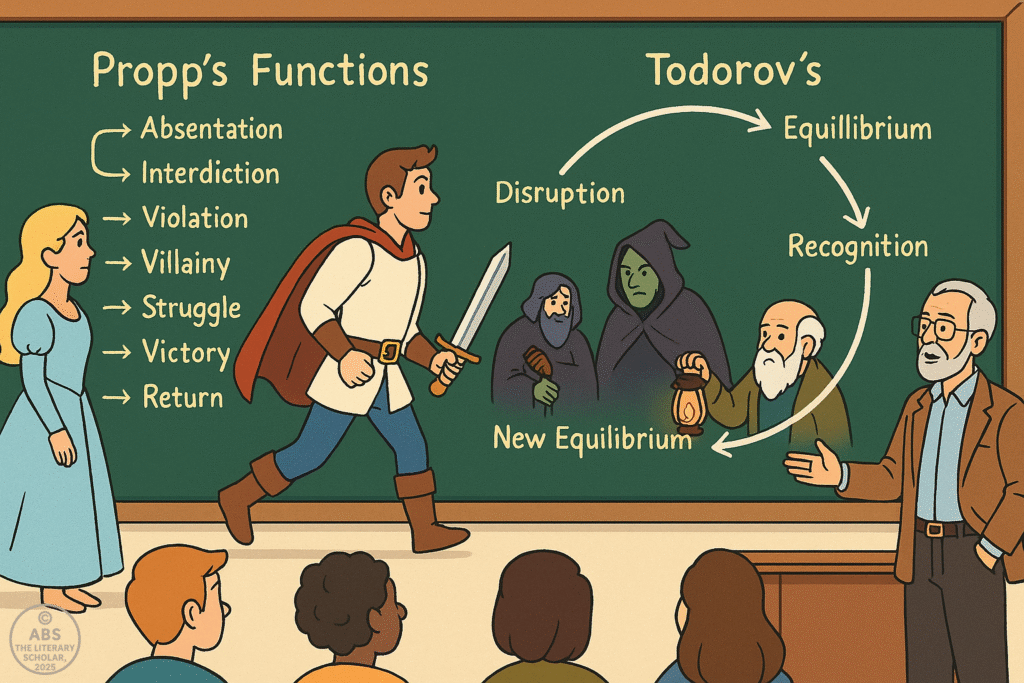

In 1928, long before “Netflix formulas” were a thing, Vladimir Propp cracked the secret code of folk tales.

In Morphology of the Folktale, Propp took 100+ Russian fairy tales and deconstructed them line by line. The result? Not chaos—but rigid structure.

Propp claimed that all fairy tales followed the same sequence of 31 narrative functions, regardless of surface plot. These included:

Absentation (someone leaves home)

Interdiction (a rule is given)

Violation (the rule is broken)

Villainy (something bad happens)

Struggle (hero and villain clash)

Victory (hero wins)

Return (homecoming with reward)

These weren’t character-specific—they were functions. Whether it was a prince, a peasant, or a frog, if the story had a quest, it likely followed this structure.

“The number of functions is limited. The sequence is always identical.”

—Vladimir Propp

Propp didn’t just offer a checklist. He gave us a blueprint: stories have a grammar.

Characters as Roles, Not Individuals

Propp also noticed that characters in folk tales weren’t psychologically complex—they were functional agents.

He reduced them to seven roles:

The Hero

The Villain

The Donor (provider of magical aid)

The Helper

The Princess (and her father)

The Dispatcher

The False Hero

These were narrative positions, not personal identities. It didn’t matter who was the villain—it only mattered that someone played that role.

This idea—that characters serve structural purposes—would become central to literary and film theory in decades to come.

Tzvetan Todorov : The Equilibrium Model

Fast forward to the 1960s, and Tzvetan Todorov enters the scene, building on Propp but refining it for modern literature.

He proposed that all narratives move through a basic structural cycle:

Equilibrium (a stable world)

Disruption (something disturbs it)

Recognition (characters realize the problem)

Attempt to repair

New Equilibrium (a changed world)

This wasn’t about Russian witches or glass slippers—it was about narrative logic. From Oedipus Rex to Jane Eyre, stories often begin in order, fall into chaos, and restore a different kind of order.

“Narrative is a transformation. It structures time itself.”

—Tzvetan Todorov

Todorov’s model brought temporality and transition into structuralism. Stories weren’t just coded—they were movements.

From Fairy Tales to Film Scripts

Propp and Todorov may have been rooted in theory, but their influence is all over pop culture.

Pixar films follow Propp’s functions.

Hollywood screenplays echo Todorov’s model.

Detective fiction, thrillers, romances—many obey these hidden grids.

Writers like Christopher Booker (The Seven Basic Plots) and Joseph Campbell (The Hero’s Journey) echo the same structuralist DNA.

But it started here—with two theorists who treated literature not as magic, but as architecture.

Structuralism Grows Up

With Propp and Todorov, Structuralism became less about words and more about structure-in-motion.

Where Saussure gave us language, Lévi-Strauss gave us myth, and Barthes gave us culture—Propp and Todorov gave us storytelling itself.

They proved that even the wildest narrative is rarely unique. It’s built from recycled parts, repeated roles, and ritualized movement. And yet—somehow—it still enchants.

Structuralism and Film Theory – Metz, Codes, and Cinematic Language

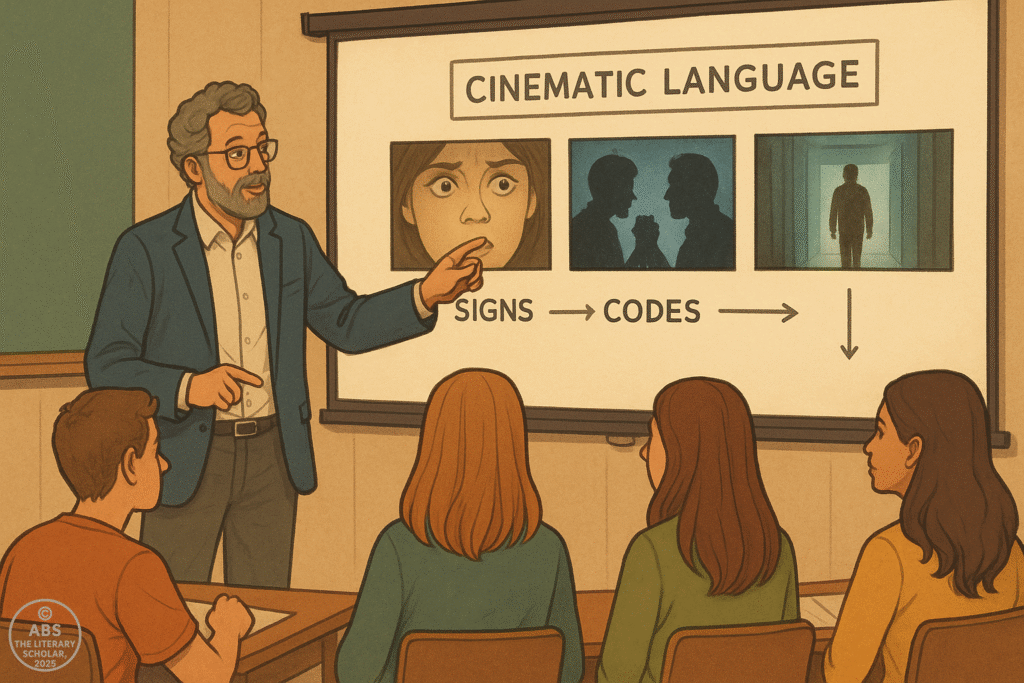

Once structuralism had cracked literature, it did what any good theory does next: moved to the movies.

After all, if fairy tales followed fixed rules and novels obeyed deep codes, why not cinema? Films are visual texts. They use signs, patterns, oppositions, symbols—and above all, language. Not the spoken kind, but cinematic language: shot-reverse-shot, montage, camera angles, mise-en-scène.

And the man who gave structure to cinema’s signs was Christian Metz.

Christian Metz: The Camera as Language

In the 1960s and ’70s, Christian Metz—heavily influenced by Saussure and Lévi-Strauss—began writing about film not as art or entertainment, but as a system of signs. To him, watching a film was like reading a coded text.

His landmark work, The Imaginary Signifier, approached cinema as a language without a tongue—a set of signs that meant something without being spoken.

“Cinema is a language in which each message is a code in motion.”

—Christian Metz

He introduced concepts like:

Syntagmatic chains: How scenes are strung together

Paradigmatic structures: How shot choices imply absent alternatives

Cinematic signifiers: Shots, cuts, camera movements functioning like words or punctuation

In short, Metz argued that cinema has grammar.

Codes and Conventions in Film

Metz and other structuralist film theorists pointed out that viewers “understand” films not because of realism, but because of shared codes:

A zoom-in signifies intimacy or danger

Cross-cutting implies simultaneity

A high-angle shot conveys vulnerability

A fade-to-black suggests closure

None of these are “natural”—they are cultural signs we’ve been trained to read.

Structuralism in literature focused on narrative functions. In cinema, it turned to visual syntax.

Binary Oppositions in Film

Just as Lévi-Strauss saw oppositions in myth, structuralist film theorists noticed oppositions driving cinema:

Light vs. dark

Male vs. female

Good vs. evil

Order vs. chaos

In Star Wars, for example, Luke Skywalker vs. Darth Vader is more than a personal battle. It’s a structure: youth vs. age, light vs. shadow, resistance vs. empire.

Structuralism revealed how these oppositions shaped audience expectations—even when stories changed.

Film Genres as Structures

Structuralist thinkers also saw genres—westerns, thrillers, horror—as coded forms. Each had its own:

Set of characters (hero, villain, sidekick, love interest)

Narrative structure (setup, conflict, climax, resolution)

Symbolic elements (guns, shadows, masks, mirrors)

A horror film wasn’t just scary. It was a textual structure of fear, suspense, and taboo—built from recognizable patterns.

“Genre is not repetition. It is ritual.”

—Jean-Louis Baudry (another structuralist-influenced theorist)

Just as Propp had done for fairy tales, structuralists did for genres: they mapped the formula.

Why Structuralism Was a Hit in Film Schools

Metz and his successors made it possible to talk about Hitchcock and Kubrick with the same tools one might use for Flaubert or Proust.

Film became legitimate scholarly material—not because of auteur theory (which focused on the director), but because of structure.

Structuralism in film studies let scholars dissect a movie like a novel:

What signs are operating?

What oppositions drive the plot?

What narrative syntagms are at play?

What ideological codes are embedded?

Suddenly, cinema was not just art—it was textual architecture.

From Popcorn to Parallels

Structuralist film theory may seem dry on the surface—but at heart, it’s poetic. It says that even the most explosive blockbuster or quiet arthouse film is made of systems and structures, signs and codes, grammar and genre.

And understanding those systems is what turns a viewer into a reader—someone who sees not just what’s on the screen, but what’s beneath it.

Structuralism in Cultural Criticism – From Myth to Mass Media

By the time structuralism left the lecture halls of linguistics and rolled through literature and film, it had one final stop: culture itself.

This is where it turned global, sharp, and thrillingly subversive.

Everything became text—not just novels and movies, but fashion trends, TV shows, comic strips, political speeches, ads for toothpaste, even wrestling matches. The world was no longer just happening—it was signifying.

And standing in the middle of this sign-filled circus was Roland Barthes, wearing a grin and holding a semiotic magnifying glass.

Barthes the Cultural Sleuth

Barthes had already deconstructed literature in Writing Degree Zero and wrestled with myth in Mythologies. But now, he went further. For him, culture was a vast language, and society spoke in codes—in what it wore, watched, consumed, and promoted.

“What the public wants is the image of passion, not passion itself.”

—Roland Barthes, Mythologies

Barthes began decoding everything from wine to striptease, toys to fashion photography. His genius lay in showing that even the most mundane item carries a mythic weight—a second layer of meaning that normalizes cultural values.

A wrestler in a mask wasn’t just fighting—he was performing good vs. evil, hero vs. traitor, law vs. chaos. It was a morality play in muscle.

Denotation vs. Connotation

Structuralist cultural critics loved to split meaning into two levels:

Denotation: the literal meaning (a red rose = a flower)

Connotation: the implied meaning (a red rose = romance, passion, Valentine’s Day expectations)

This wasn’t just about roses. It was about everything. A politician’s outfit, a corporate logo, a fast-food slogan—each came loaded with hidden ideologies.

Barthes called this myth-making, where signs are naturalized, made to seem obvious when they’re culturally constructed.

The Myth of the “Natural”

One of structuralism’s most explosive claims in cultural criticism was this:

Nothing is natural. Everything is constructed.

The way gender is shown in ads, the “innocence” of children’s toys, the logic of who gets to be a superhero or a CEO—these aren’t truths, they’re structures masquerading as common sense.

Barthes showed that “normal” was just habitual myth, and the critic’s job was to tear it apart.

“Myth is a type of speech chosen by history.”

—Barthes

Everyday Life as Text

For structuralist critics, analyzing a McDonald’s commercial wasn’t beneath them. It was the exact place to look for modern myth.

The golden arches? Sanctuary and efficiency

The “Have it your way” slogan? Freedom within consumerism

The smiling cashier? Emotional labor as branded friendliness

Nothing was innocent. Culture was code.

This attitude birthed modern cultural studies, where scholars could read Game of Thrones and Beyoncé with the same tools used on The Iliad.

Lévi-Strauss: Culture as System

Let’s not forget Claude Lévi-Strauss, who gave this movement intellectual muscle. In his study of myths, kinship, and tribal rituals, he argued that cultures—ancient or modern—organize life through binary oppositions:

raw/cooked

nature/culture

male/female

sacred/profane

These binaries aren’t universal truths. They’re mental grids used by societies to create meaning.

In other words, we don’t just live in culture—we live in structure.

Pop Culture as Myth Factory

Today’s influencers, YouTube thumbnails, Marvel villains, reality TV tropes—they all echo the myth-making machines Barthes warned us about.

A celebrity meltdown? Tragedy

The underdog winning a dance show? Hero’s journey

A presidential photo op with puppies? Symbolic moral hygiene

Barthes would be having a field day on Instagram.

Structuralism’s Cultural Legacy

Structuralism didn’t just make literary theory smarter—it made the world readable.

It taught us that behind every ad jingle, fashion craze, or viral tweet, there’s a system of signs quietly reinforcing how we think reality works.

And once you’ve seen the code, it’s hard to unsee it.

The Limits of Structuralism – Cracks in the Code

Structuralism stormed through literature, cinema, and culture like a theory on a mission. It gave critics power tools: signs, binaries, codes, oppositions. But eventually, every structure—no matter how elegant—starts to show its cracks.

And just like that, the very tools that built the house began to tear it down.

Because what happens when the system stops making sense? When signs misbehave? When meanings multiply instead of stabilize?

That’s when structuralism started to collapse under its own brilliance, and new thinkers whispered, “What if meaning isn’t just hidden… but endlessly deferred?”

The First Rumblings of Doubt

Even some of the most devoted structuralists began to suspect that their quest for order had a fatal flaw.

If everything is a sign, who decides the meaning?

If oppositions rule myths, what about stories that resist neat binaries?

If language is a system of differences, what anchors those differences?

In short: what if meaning isn’t fixed—but floating?

“There is nothing outside the text.”

—Jacques Derrida

This was the intellectual mic-drop that shattered the structuralist party. Derrida, and the post-structuralists who followed, weren’t content mapping the structures of meaning. They questioned whether meaning existed in any stable, reliable form at all.

The Problem of the Signifier

Structuralism had placed a lot of faith in Ferdinand de Saussure’s idea of the sign: the signifier (word, image, symbol) and the signified (the concept it represents).

But what if the signifier isn’t tied down to a single signified?

What if it slides, shifts, winks, and mutates depending on:

Context

Culture

Reader interpretation

Power dynamics?

This is where the idea of the “slippage” of the signifier came in.

Suddenly, a rose wasn’t just a rose—it could be romantic, sarcastic, nostalgic, political, or all of them at once. Meaning was no longer a product of structure. It was a playground of uncertainty.

Barthes Reconsiders

Even Barthes, the high priest of structuralist myth-hunting, began to change his tune.

In his later works, like The Pleasure of the Text and S/Z, he questioned whether structured analysis was enough. He moved toward plural readings, textual play, and the idea that the reader—not the structure—creates meaning.

“The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author.”

—Barthes

This wasn’t just poetic rebellion. It was a declaration of war on the idea that a text had one “true” structure or message. The era of stable signs was over.

Structuralism’s Blind Spots

As more critics joined the rebellion, they pointed out the ideological blind spots of structuralism:

It ignored history: Structuralism treated texts as timeless systems, not products of historical conflict.

It avoided politics: Who benefits from these codes? Who is excluded?

It dismissed individuality: Structuralism loved rules, not exceptions. But what about voice, emotion, identity?

Writers, feminists, postcolonial thinkers, and psychoanalysts began poking holes:

Why are certain voices considered “myth” while others are silenced?

What about race, gender, and class in those oppositional structures?

Structuralism, they argued, was brilliant—but it flattened the human experience.

The Turn Toward Play

One of the most crucial turning points came with Derrida’s notion of play. He suggested that structures only seem stable because we pretend they are.

But deep down, meaning is made through:

Difference

Delay

Deconstruction

This was not nihilism. It was freedom. If structuralism was a cathedral, post-structuralism opened the side door and let in graffiti, jazz, and contradiction.

“Structure is not simply a structure but a structured play of differences.”

—Derrida

Legacy of a Collapsing System

So did structuralism fail?

No. But it reached its limits.

It showed us how texts are built—but not always how they breathe. It gave us form, but not always freedom. Its collapse wasn’t a failure—it was the foundation for new theories to rise.

In a way, structuralism was never about permanence. It was about pattern. And in recognizing its own fragility, it gave birth to the most liberating idea of all:

There is no final meaning. Only the dance of interpretation.

The Final Frame – Structuralism at Its Edge

By the time Structuralism had mapped myths, decoded fashion, dissected literature, and diagrammed detective novels, something curious had begun to stir—a crack in the mirror it held up to language.

At first, it was just a tremble. A small doubt.

But it would soon grow.

This section isn’t about what replaced Structuralism. It is about how Structuralism, in all its ambition, began to sense the limits of its own scaffolding.

The High Cathedral of Codes

Structuralism had promised clarity.

Saussure taught us to think of language as a system of differences.

Lévi-Strauss mapped culture like a syntax.

Barthes saw fashion and film as mythologies built on signs.

Todorov and Propp sketched narratives like scientific diagrams.

Greimas balanced meaning across perfect binary axes.

For a while, it worked. It gave literary scholars the thrill of system, the elegance of geometry. Meaning was not subjective fluff—it was structural form. Even emotions could be charted.

But behind the grids and triangles, something had begun to shift.

The Problem of Closure

Stories, Barthes taught us, moved through codes—hermeneutic, proairetic, symbolic.

But not all stories ended as neatly as Propp’s Russian fairy tales.

What happens to codes when:

A story refuses to resolve?

A myth contradicts itself?

A poem eludes interpretation?

Scholars began to see that meaning wasn’t always cooperative. The structure was there, yes—but what about the gaps? The silences? The unruly metaphors that wouldn’t stay pinned down?

Even Barthes, once the most devout structuralist, began to drift.

When the Center Trembles

Structuralism, for all its intellectual power, relied on stability:

The stability of the signifying system.

The stability of narrative logic.

The stability of oppositions and categories.

But what if that stability was only an illusion?

What if:

“The center is not the center.”

That whispered idea began to travel—first among the French thinkers of the late 1960s, then across universities like wildfire.

There was no single moment when Structuralism ended.

Only a growing awareness that it was not the final theory—but a pivotal one.

Signs That Couldn’t Be Contained

The more scholars read texts, the more they saw:

Codes within codes.

Binaries that collapsed.

Interpretations that multiplied instead of resolving.

Structuralism had treated the reader as a decoder. But slowly, a new figure was emerging:

Not the decoder.

Not the critic.

But the co-creator.

The text, once thought to be structured and sealed, was beginning to look more like a field of play.

A Soft Knock on the Door

Let us be clear: Structuralism in literature was never defeated.

It was complicated.

Its principles still shape our classrooms, our analyses, and our instinct to look for systems beneath the surface. But toward the end of its reign, something walked in.

Not a challenger with weapons, but a whisper with questions.

What if the sign doesn’t just differ—but defers?

What if texts unravel themselves?

What if language betrays itself the moment it tries to say anything at all?

The questions had entered. The answers would soon follow.

ABS, The Literary Professor, Reflects:

Structuralism came like a brilliant architect—with compasses, maps, and chalkboards.

It built monuments of theory, taught us to see meaning in myths, codes in clothing, patterns in poetry.

But monuments crack. Maps fade.

As the scaffolding of signs begins to shake, another movement waits outside the gates—less orderly, more elusive.

And so we stand at the threshold.

One foot still inside the grid.

The other… ready to wander.

Scroll Index: Explore Literary Theory Explained

(Click any to begin)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance