Hopkins, Nursery Rhymes, and the Great Metrical Rebellion

ABS Believes:

Poetic rhythm shouldn’t behave like a parade. It should behave like a toddler on sugar: unpredictable, adorable, and terrifyingly free.

The Meter That Misbehaved

There are two types of rhythm in this world:

The kind that walks into a room, straightens its tie, and recites Shakespeare in pentameter.

And the kind that somersaults through the window yelling, “Glory be to God for dappled things!” before landing in a puddle of polysyllables.

Guess which one Sprung Rhythm is.

Most poetry follows the rules. Stressed, unstressed. Five feet. Ten syllables. English teachers nod in approval. But some lines—like rebellious teenagers or caffeinated grasshoppers—just don’t want to be told when to thump and when to tiptoe.

Enter Sprung Rhythm. It doesn’t march—it bounces, kicks, pauses, gallops, whispers, and then bursts into song. It’s the literary equivalent of jazz on a trampoline. And while most metrical forms politely shake hands with structure, Sprung Rhythm throws it a whoopee cushion and pirouettes away.

Invented—or at least resurrected and dramatized—by the Victorian poet-priest Gerard Manley Hopkins (a man who managed to combine spiritual ecstasy with poetic chaos), Sprung Rhythm was a direct challenge to the metrical tedium of his time. It was his way of saying: “God made thunder, not tick-tock.”

But here’s the twist: Hopkins didn’t invent the instinct to spring. Children’s rhymes were already at it. Limericks were springing all over the place. Even Old English poetry had a thing for stressed beginnings. Hopkins just gave the anarchy a name—and a halo.

This five-part poetic adventure will take you through the bouncy lanes of Sprung Rhythm—from its heady definition to its secret life in nursery rhymes, from Hopkins’s dappled verse to the limerick’s shameless jig.

Hold onto your syllables.

We’re about to spring into rhythm.

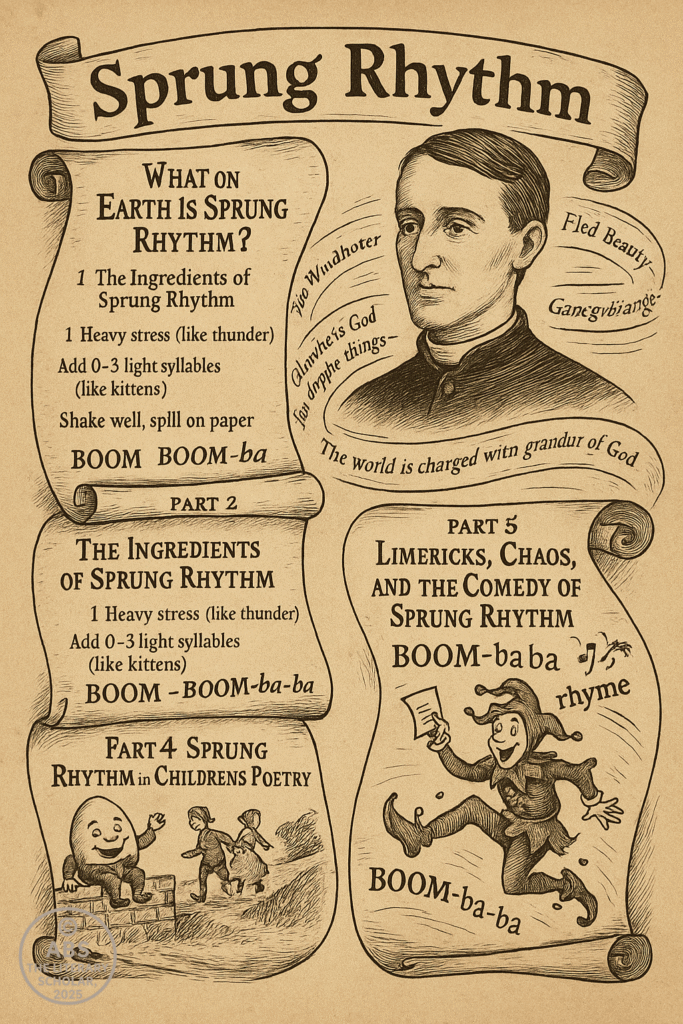

📖 PART 1: What on Earth Is Sprung Rhythm?

🥁 Subtitle: When poetry started leaping instead of walking

Let’s begin with a confession: most poetry behaves. It walks in lines, counts its steps, and waits patiently for the rhyme to arrive like a punctual Victorian dinner guest.

But then along came Sprung Rhythm—and suddenly, poetry showed up uninvited, did cartwheels on the carpet, and set the dinner table on fire.

So… what exactly is it?

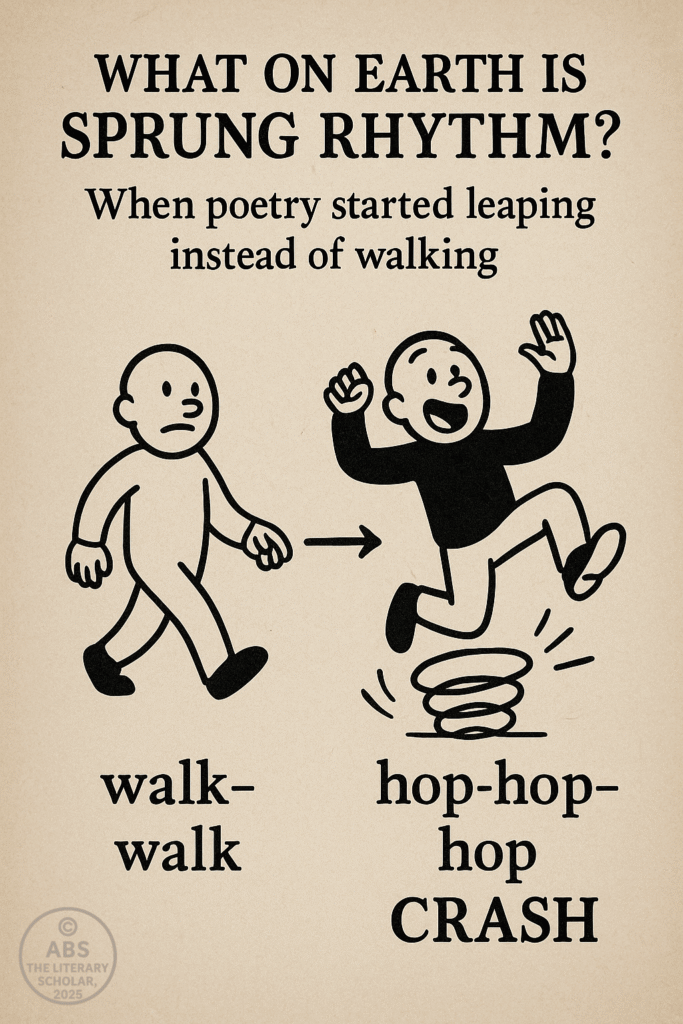

Sprung Rhythm is a poetic meter where every foot begins with a stressed syllable—a nice firm BOOM—and is followed by a variable number of unstressed syllables, which may or may not behave. The number of syllables after the stress? That’s up to the poet, and possibly their mood, the moon phase, and how many cups of tea they’ve had.

Where traditional meter says,

de-DUM de-DUM de-DUM de-DUM de-DUM (iambic pentameter)

Sprung Rhythm says,

DUM-ba-da / DUM / DUM-da-da-da / DUM-dum (and breathe… maybe)

It’s rhythm without a leash.

⚖️ Traditional Meter vs. Sprung Rhythm

Traditional meter is like military school:

Neatly dressed syllables.

Five feet in a line.

No one talks out of turn.

Sprung Rhythm is more like a toddler on a sugar high playing the drums during a jazz concert.

Every line starts with a stressed syllable and then… chaos ensues.

The length of the foot is not fixed.

You don’t scan it. You survive it.

Traditional meter: walk–walk–walk.

Sprung Rhythm: hop–hop–hop–CRASH.

It’s poetry that vaults, rebounds, stammers, sings, and sometimes pants at the finish line. It resists predictability the way cats resist instructions.

🎷 An Analogy (Because We’re Fancy Like That)

If traditional meter is a metronome, Sprung Rhythm is a jazz solo played by a caffeinated child with ADHD who just discovered percussion. It’s instinctive. It’s alive. It doesn’t care what Wordsworth thinks.

In fact, Sprung Rhythm doesn’t care what anyone thinks. It has a spring in its step and a holy fire in its syntax. It’s the beat that keeps breaking the mold.

🐱 “Ding-Dong Bell…”: A Surprise Example

Want to see Sprung Rhythm in the wild?

“Ding-dong bell, / Pussy’s in the well.”

Yes. That horrifying nursery rhyme from your childhood. The one that made you question morality before you could spell “morality.” That line is rhythmically sprung.

It begins with stress (“DING”) and then tap-dances through an erratic beat pattern that oddly resembles natural speech—if natural speech involved traumatized cats and medieval children.

It’s playful. It’s unpredictable. It’s… somehow poetic. And it’s been with us longer than Gerard Manley Hopkins’s beard.

Sprung Rhythm isn’t about disorder for the sake of drama—it’s about mimicking real speech, with all its hiccups, breaths, leaps, and echoes. It captures that spark where poetry becomes more than music—it becomes voice.

And as we’ll soon discover, that voice had a priest behind it, armed with a pen, a prayer, and a passion for the dappled.

PART 2: The Ingredients of Sprung Rhythm (Not Found in Your Regular Poetic Cookbook)

🍲 Subtitle: Stressed, Unstressed, and Deliciously Unpredictable

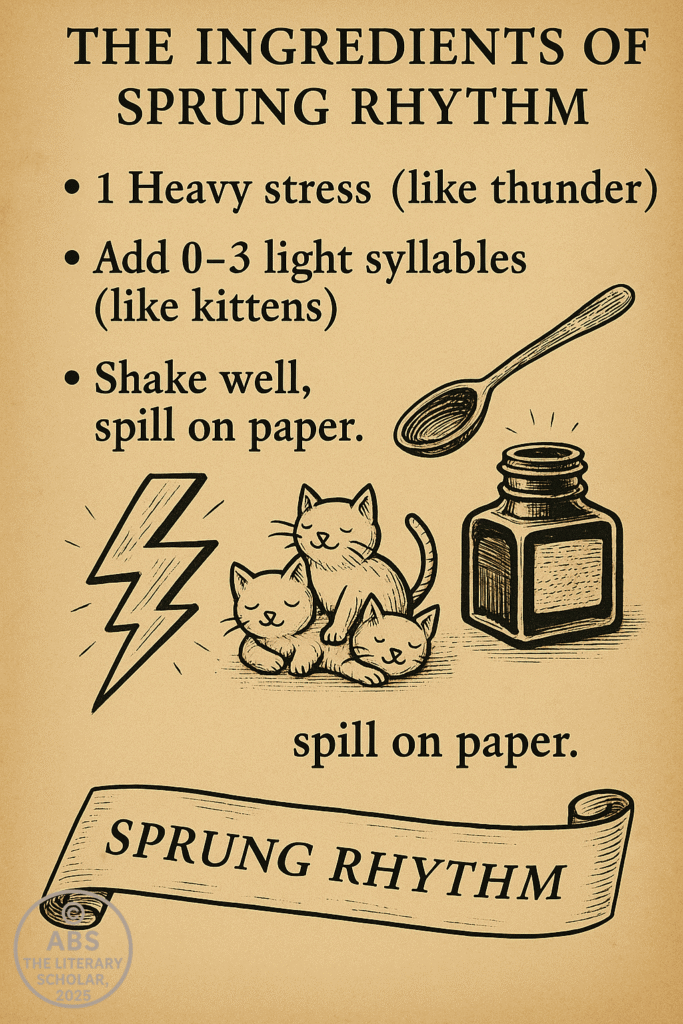

If traditional meter is like baking a cake with exact measurements (5 iambs per line, sifted twice), then Sprung Rhythm is like tossing thunder, kittens, and instinct into a literary blender and hitting “pulse.”

Let’s open the recipe scroll.

🥄 The Core Recipe

1 Heavy Stress (preferably thundering—think Zeus clearing his throat)

0 to 3 Light Syllables (optional fluff—think kittens rolling down a hill)

Mix until irregular

Pour freely across the line

Ignore the judgment of formalist grammarians

Serve unscannable, preferably with dappled metaphors

This is not the Queen’s meter. It’s the meter of wild priests, poetic children, and anyone who has ever tried to rhythmically describe lightning while on a hill at dawn.

🦶 Footloose and Fancy-Free: Types of Sprung Feet

In Sprung Rhythm, **anything goes—**as long as the foot begins with a stressed syllable. It’s all about the kickoff. Once you boom, you can tiptoe.

Monosyllabic foot:

BOOM. (And that’s it. The foot is done. Mic drop.)

Trochee:

BOOM-ba (Classic stress-unstress. Think of an elephant with a limp.)

Dactyl:

BOOM-ba-ba (Like galloping with too many shoes on.)

Molossus? Rare.

BOOM-BOOM-BOOM (Used only when you’re writing about apocalypse, war drums, or very enthusiastic toddlers.)

Sprung Rhythm lets you play footsie with tradition, but with steel-toed boots.

⏸️ Caesura: For Dramatic Punctuation (and Reader Anxiety)

Sprung Rhythm occasionally throws in a caesura—a pause, a breath, a poetic sigh, or a literary slap.

Not mandatory.

Not predictable.

But always effective when you want the reader to wonder, “Wait, did the poem just stop breathing?”

Use it to simulate natural human thought—which, if we’re being honest, is full of hesitations, interruptions, and mental side quests.

The world is charged with the grandeur of God —

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil…

That dash? That’s the caesura holding its breath.

🗣️ Why It Matters: Poetry That Talks Like Us

Nobody in real life speaks in iambic pentameter—unless they’re trapped in a Shakespearean soliloquy or have recently been knighted.

People rant, rush, pause, sputter, repeat themselves, and shout without warning. That’s what Sprung Rhythm captures.

It’s not robotic.

It’s not symmetrical.

It’s not safe.

It’s alive.

Hopkins wasn’t trying to be clever—he was trying to trap raw life on the page.

🧦 The Irony: Victorian Chaos

Here’s the best part. This rebellious, electric, wild, spring-loaded rhythm? It was formalized in the Victorian Age.

Yes, that same era that invented corsets, etiquette books, and chairs you weren’t allowed to sit on.

Gerard Manley Hopkins was out here inventing poetic jazz while everyone else was writing neat quatrains about daffodils and decorum.

Sprung Rhythm is the Victorian Age’s poetic punk rock—sneaking wildness into a world of decorum, one stressed syllable at a time.

🧁 Final Tasting Note:

Sprung Rhythm is not about breaking rules. It’s about breaking free.

It gives poets permission to sound like themselves—even when they sound strange, breathless, holy, or utterly unscannable.

And when done right? It’s less like reading and more like falling through a poem headfirst.

✝️ PART 3: Hopkins the Rhythm Rebel

Subtitle: Gerard Manley Hopkins – Saint of Stressed Syllables

Before beat poets snapped fingers, before slam poets yelled in basements, before anyone thought to misplace a comma for artistic effect—Gerard Manley Hopkins was already sprinting across poetic lines with a theology degree and a metrical mallet.

He wasn’t just writing poetry.

He was composing liturgical jazz on a page.

🤯 The Confession: “I Invented a New Rhythm. Also, Sorry.”

Hopkins once wrote (casually, in a letter, as though inventing a metrical revolution were a side hobby):

“I wish I could publish some of the verse I write… in what I call Sprung Rhythm.”

As if he’d just come up with a new jam recipe and wasn’t sure if the vicar would approve.

But here’s the twist:

He didn’t just invent it.

He felt it.

He saw it in the wings of birds, in the flicker of trout, in the shimmer of light through leaves. Hopkins wanted his lines to pulse with the “inscape” of things—their inner essence, their shape, their rhythm, their God-given pattern.

And traditional meter? Too tame. Too symmetrical. Too Elizabethan, thank you very much.

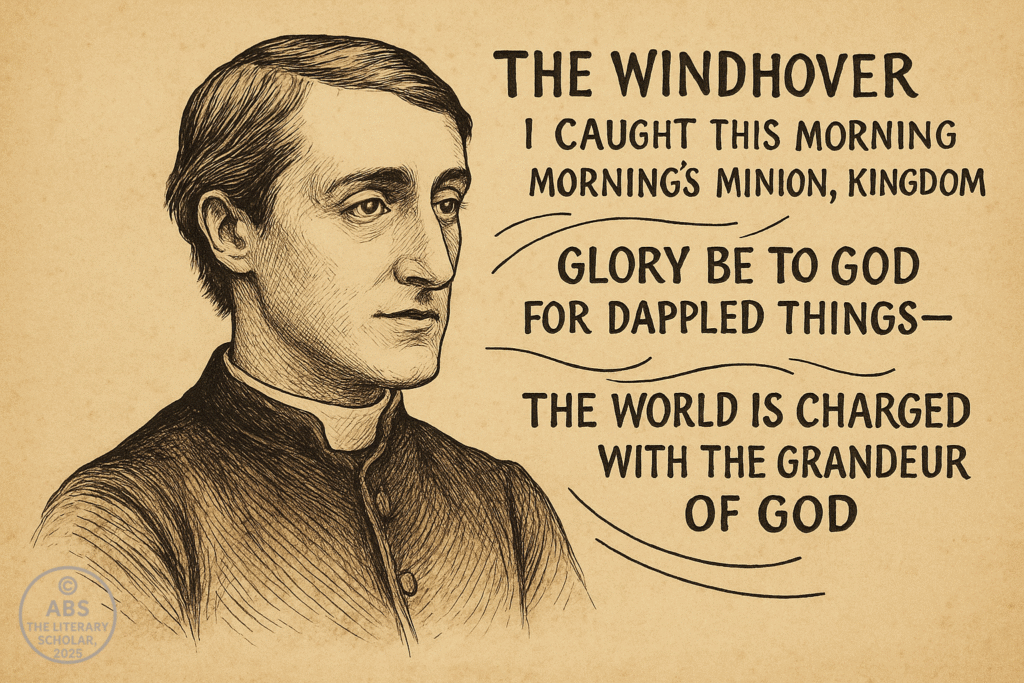

⚡ The Windhover, Pied Beauty, and Other Metrical Firecrackers

“Glory be to God for dappled things—”

That’s not just a line. It’s a spiritual outburst in poetic form.

Each word lands like a footstep on divine soil—stress after glorious stress, like drumbeats in a stained-glass chapel.

In The Windhover, Hopkins doesn’t describe a bird—he becomes one.

“I caught this morning morning’s minion, kingdom

Of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon…”

Try saying that aloud and not falling into the rhythm like a poetic trampoline.

These are not calm lines. They don’t sit in the corner sipping tea.

They burst, spin, fling, explode, and then collapse into glory.

💥 Why Walk When You Can Spring?

Hopkins’s rhythmic logic was holy and unhinged:

“Why walk politely through a line

when you can spring over it

like a wild deer on fire?”

If Wordsworth is a stroll in the woods, Hopkins is a forest fire with theology.

His feet didn’t want to land every second syllable.

They wanted to land whenever the heart pounded, the spirit gasped, or the language broke open.

😑 Critics: “This Is Unreadable.”

🧎 Hopkins: “Read It Again. Slowly. Then Cry.”

Hopkins wasn’t adored in his lifetime. Most editors blinked, shuddered, and returned his manuscripts wrapped in caution tape.

Some said his poems didn’t scan.

To which Hopkins may have replied:

“Scan? My dear, they don’t scan.

They sear.”

🎼 His Rhythm Was Theology

Hopkins didn’t see Sprung Rhythm as artistic rebellion.

He saw it as spiritual precision.

Each stress was a divine heartbeat.

Each syllable—a breath in God’s syntax.

He wrote like the universe sounded before grammar got in the way.

🕊️

Gerard Manley Hopkins didn’t just bend the rules.

He baptized the break.

And somewhere between the boom of a syllable and the hush of a line break, he made rhythm sacred—and poetry spring eternal.

Hopkins, God, and the Metrical Madness of Sprung Rhythm

When a Jesuit Poured Thunder into Verse

When a Jesuit Poured Thunder into Verse

Before there were workshops on “writing from the soul,” there was Gerard Manley Hopkins, a Victorian priest with the heart of a mystic, the syntax of a gymnast, and the metrical instincts of a divine beatboxer.

Hopkins didn’t just use Sprung Rhythm—he married it, lit candles around it, and wrote poetry like a man possessed by the Holy Ghost and a jazz drummer simultaneously.

This part is devoted entirely to him: his poetic style, his sprung technique, and the specific poems where this rhythm roars, ripples, or rattles like a liturgical earthquake.

Hopkins and His Wild Love Affair with Rhythm

Hopkins and His Wild Love Affair with Rhythm

For Hopkins, Sprung Rhythm was not a stylistic experiment. It was the fingerprint of creation—the sound of a world that glories in God through irregularity.

“Sprung Rhythm is the nearest to the rhythm of prose, that is the native rhythm of speech.”

—Hopkins, in a letter to Robert Bridges

Translation: He wanted poetry that breathed, stammered, erupted, danced—and still praised the divine.

Signature Features of Hopkins’s Sprung Rhythm:

Signature Features of Hopkins’s Sprung Rhythm:

Every foot begins with a stress

Followed by a variable number of unstressed syllables (often 0–3)

Use of alliteration, internal rhyme, and asymmetry

A deliberate sense of urgency or ecstasy

Punctuation that feels like cardiac arrest and resurrection

Now, let’s see Sprung Rhythm in the field—Hopkins’s poems, line by line, springing into life.

1. The Windhover

1. The Windhover

“I caught this morning morning’s minion, kingdom

Of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon…”

Hopkins doesn’t so much begin the poem as he catapults us into it. The opening is an eruption of stressed syllables (“caught,” “morn-,” “morn-’s,” “min-”), launching us into falcon-flight.

Sprung Rhythm effect: Mimics the swoop and dive of a falcon mid-air.

Feet like: BOOM-boom / BOOM-ba-ba / BOOM

It reads like breathless awe, orchestrated through controlled metrical chaos.

2. Pied Beauty

2. Pied Beauty

“Glory be to God for dappled things—”

The first line hits hard. It’s a monosyllabic stress explosion.

“For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;”

The list grows breathlessly: sound bouncing like light on water.

The rhythms are not symmetrical. They mimic nature: irregular, beautiful, and blessedly chaotic.

Hopkins’s world is not neat. It is “counter, original, spare, strange.” Just like his rhythm.

3. God’s Grandeur

3. God’s Grandeur

“The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;”

This is Hopkins preaching through percussion.

That first line: “The WORLD is CHARGED with the GRANdeur of GOD.” → Stress party.

Then: “It will FLAME OUT…” — another BOOM-start.

His rhythm crackles like electricity. The lines feel alive, not scanned.

4. Binsey Poplars

4. Binsey Poplars

“My aspens dear, whose airy cages quelled,

Quelled or quenched in leaves the leaping sun…”

Alliterative hammering of “quelled” and “quenched”

Sprung Rhythm matches grief — the rhythm stumbles and stutters.

This poem mourns the felling of trees, and Hopkins lets the line collapse gently, like a tree falling.

This is sprung sorrow.

5. The Wreck of the Deutschland

5. The Wreck of the Deutschland

Hopkins’s longest and wildest ride.

“Thou mastering me

God! giver of breath and bread;

World’s strand, sway of the sea…”

This isn’t just Sprung Rhythm. It’s Sprung Tsunami.

Unpredictable pauses.

Violent shifts.

Emphatic stresses and enjambments.

The poem reads like drowning—gasps, waves, silences—and Hopkins uses rhythm to imitate both chaos and spiritual transcendence.

6. As Kingfishers Catch Fire

6. As Kingfishers Catch Fire

“As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame…”

The opening line ignites—all stresses and bright bursts.

It’s lyrical combustion.

Every line springs forward with poetic muscle.

He weaves Sprung Rhythm with theology: each soul sings its own note, just as each foot kicks off with a unique beat.

7. Carrion Comfort

7. Carrion Comfort

“Not, I’ll not, carrion comfort, Despair, not feast on thee…”

This is Sprung Rhythm as emotional wrestling.

Stressed syllables tumble like punches.

The poet is in battle with God—and so is the meter.

The rhythm stumbles, rises, breaks, and recovers—mirroring the crisis.

8. That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection

8. That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection

The title is a sprint. The poem? A cosmic detonation.

“Cloud-puffball, torn tufts, tossed pillows… are all at an end.”

Alliteration + Sprung Rhythm = verbal fireworks.

It’s chaotic precision—Hopkins at his most breathless and profound.

The final stanza explodes into:

“In a flash, at a trumpet crash,

I am all at once what Christ is…”

If this poem were music, it would be Mahler falling down stairs—with grace.

What Hopkins Did with Sprung Rhythm

What Hopkins Did with Sprung Rhythm

He didn’t just write poems.

He choreographed emotion into syllables.

He turned theology into rhythm.

Nature into meter.

Pain into percussion.

Praise into pounding beats.

Sprung Rhythm in Hopkins is not an accessory—it’s the DNA of the voice.

Final Line from the Choir Loft

Final Line from the Choir Loft

Hopkins taught us that poetry doesn’t have to march.

It can soar, plunge, stammer, and sing—in fits and starts, in thunder and tremble.

His verses do not walk.

They leap.

PART 4: Sprung Rhythm in Children’s Poetry (Because Kids Have Never Marched in Metre)

PART 4: Sprung Rhythm in Children’s Poetry (Because Kids Have Never Marched in Metre)

Subtitle: Ding-Dong Bells and Syllabic Circus Acts

Subtitle: Ding-Dong Bells and Syllabic Circus Acts

Let’s be honest—children’s poetry has always been one beat away from bedlam. Which is precisely why it’s genius.

While grown-up poets were busy arguing over whether a line should end with a trochee or a headache, Mother Goose was already bouncing through verses like she was on a sugar-fueled pogo stick.

Accidental Brilliance: The Nursery Rhyme Revolution

Accidental Brilliance: The Nursery Rhyme Revolution

Most nursery rhymes were not written to dazzle academics. They were written to keep children amused long enough not to stick forks in sockets.

But in the process, they stumbled—gracefully—into something rhythmically sublime.

Take this:

“Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall…”

Scan it. Stress it. Shout it.

It doesn’t walk—it springs. First a boom, then a bounce, then a slightly ominous ending involving shattered eggs and governmental incompetence.

It’s pure Sprung Rhythm. Whether Mother Goose knew it or not, she was out-Hopkins-ing Hopkins.

Poetic Psychology: Why Your Brain Remembers “Jack and Jill”

Poetic Psychology: Why Your Brain Remembers “Jack and Jill”

The human brain is a drama queen. It remembers what moves, what repeats, what sounds slightly dangerous but ends with a rhyme.

That’s why no one recalls the third line of a Shakespeare sonnet without trying, but every 6-year-old knows this:

“Jack and Jill went up the hill / To fetch a pail of water.”

Again—stress, bounce, fall. It’s a mini-melodrama in Sprung Rhythm, disguised as a bedtime chant.

It’s not just poetry. It’s memory architecture in disguise.

Why Sprung Rhythm Feels Like Childhood

Why Sprung Rhythm Feels Like Childhood

Sprung Rhythm isn’t just a poetic technique. It’s how children experience language.

They shout when excited → STRESS!

They mumble through the boring bits → unstress, unstress.

They repeat lines until the universe collapses.

They turn rhythm into a game.

Hopkins thought he was inventing a new metrical system. Turns out, every toddler had beaten him to it—with a rattle and a rhyme scheme.

Mother Goose vs. Gerard Manley Hopkins

Mother Goose vs. Gerard Manley Hopkins

Let’s be clear: Hopkins gave Sprung Rhythm its name, rules, and religious overtones.

But Mother Goose?

She gave it joy, chaos, and probably mild emotional trauma involving talking livestock.

Hopkins made it divine.

Goose made it adorable and creepy.

And that, dear reader, is how the poetic foot learned to skip.

Final Word Before We Tumble Down the Hill

Final Word Before We Tumble Down the Hill

So next time you hear a child shout “Baa baa black sheep,” realize you’re not just listening to a nursery rhyme.

You’re hearing a sprung-rhythm incantation, passed down through centuries of bouncing syllables and unhinged joy.

Poetry never behaved in childhood—and maybe that’s why we loved it most back then.

PART 5: Limericks, Chaos, and the Comedy of Sprung Rhythm

PART 5: Limericks, Chaos, and the Comedy of Sprung Rhythm

Subtitle: There once was a meter that ran… and ran… and ran…

Subtitle: There once was a meter that ran… and ran… and ran…

Let’s admit it—limericks are the poetic equivalent of that one cousin at weddings: loud, mischievous, slightly inappropriate, but everyone secretly loves them more than the groom.

And while traditional meter stands tall and dignified in its iambic corset, the limerick comes in sprung and snickering, wearing a funny hat and dancing out of step. It’s Sprung Rhythm in a comic costume, and it’s been pulling poetic pranks for centuries.

Limericks Are Secretly Rebellious

Limericks Are Secretly Rebellious

They look short. They sound simple. They’re often about bearded men from Nantucket. But under that playful mask is a rebellion in rhyme.

Limericks don’t follow classical meter.

They mock it.

They twist it.

They trip over it on purpose—and then rhyme something absurd with “bucket.”

And the secret to their swagger? Sprung Rhythm.

The Trick Behind the Laugh: Limerick Structure

The Trick Behind the Laugh: Limerick Structure

A classic limerick follows the AABBA rhyme scheme and has a specific pattern of anapestic meter — that is, ba-ba-BOOM.

Here’s how it rolls:

BOOM-ba-ba / BOOM-ba-ba (A)

BOOM-ba-ba / BOOM-ba-ba (A)

BOOM-ba-ba (B)

BOOM-ba-ba (B)

BOOM-ba-ba / BOOM-ba-ba (A)

Now that’s the formal structure. But like any rule worth knowing—the best limericks immediately break it.

They might squish an extra syllable.

They might pause in the middle.

They might crash into the rhyme like a unicycle at full speed.

It’s not meter. It’s momentum.

Anapests on the Loose: The Tipsy Rhythm

Anapests on the Loose: The Tipsy Rhythm

Limericks are often written in anapests—that’s ba-ba-BOOM, a light-light-stress pattern.

Think of it as a drunken gallop.

Or a jester rolling downhill with a tambourine.

The first two lines introduce a rhythm. The third and fourth lines cut it short. The fifth line crashes in with flair, sometimes wisdom, sometimes a punchline. Always surprise.

There once was a man from Peru,

Who dreamed he was eating his shoe.

He woke with a fright,

In the middle of night—

To find that his dream had come true.

Sprung Rhythm in limericks means comedy with cadence. It lets the language bounce like a giggling trampoline.

Why Limericks Endure (While Sonnets Need a Nap)

Why Limericks Endure (While Sonnets Need a Nap)

People return to limericks because they play with rhythm the way cats play with gravity.

Sprung Rhythm makes them misbehave—and misbehavior is memory-forming.

It’s silly.

It’s compact.

It’s smart enough to be dumb on purpose.

Traditional forms want to be respected.

Limericks want to be remembered—preferably with a chuckle and a raised eyebrow.

And let’s be honest:

Nothing rhymes with “pentameter.”

But everything bounces to a good limerick.

Final Line Before We Spring Off Stage

Final Line Before We Spring Off Stage

Limericks are where Sprung Rhythm cuts loose—not for praise, not for theology, not for grandeur. Just for fun.

They’re proof that rhythm doesn’t have to be holy. Sometimes, it can just be hilarious.

Sprung Rhythm After Hopkins: Who Else Dared to Bounce?

Sprung Rhythm After Hopkins: Who Else Dared to Bounce?

Gerard Manley Hopkins may have coined and sanctified Sprung Rhythm, but after him, a few brave poets dipped their toes—and occasionally their entire poetic torso—into this beautifully chaotic meter. While none wielded it with Hopkins’s Jesuit zeal and thunderous diction, echoes of Sprung Rhythm do ripple through modern English literature.

Here are a few poetic descendants and rhythmical rogues:

1. Dylan Thomas

1. Dylan Thomas

“The force that through the green fuse drives the flower…”

Thomas didn’t name it Sprung Rhythm, but he definitely sounded like it.

His poetry is all stress-heavy syllabic avalanches, unruly pauses, and hypnotic cadence.

He once said he wrote by ear, not meter—Hopkins would’ve leapt with delight (in an anapestic pirouette).

2. W.H. Auden

2. W.H. Auden

Auden sometimes slipped into Hopkins-esque sprung cadences in his more reflective poems. His meter is often loose, driven by stress-timed phrasing more than syllable count—especially in lyrical and dramatic monologues.

He also admired Hopkins deeply. You can hear it in the internal echoing, the sense of tension, the spiritual undertow.

3. Ted Hughes

3. Ted Hughes

Hughes, with his mythic violence and animalistic rhythms, frequently created poems that felt sprung—even if he didn’t formally call them that.

His lines begin with heavy stresses and stampede forward with raw, instinctive power.

He was rhythm-first, and content second—very much in Hopkins’s metaphysical mud-tracks.

4. Seamus Heaney

4. Seamus Heaney

Heaney’s North and Station Island occasionally employ rhythms that mirror the flexible-footed, breath-based model of Sprung Rhythm.

He dug into the earth—not just metaphorically, but rhythmically. His lineation sometimes mimics natural speech with a deep lyrical pulse.

5. Geoffrey Hill

5. Geoffrey Hill

A direct heir in linguistic density and metrical rebellion, Hill’s poetry often grapples with Hopkinsian rhythm—though sometimes it’s more like wrestling than homage.

His verse is densely packed with sound play, stresses, and spiritual weight—a modern intellectual’s version of Sprung Rhythm.

Final Word on the Rhythm That Leaps

Final Word on the Rhythm That Leaps

Sprung Rhythm was never mainstream.

It never wanted to be.

It lived in dappled margins, falcon dives, nursery rhyme cadences, and limerick pratfalls. Hopkins gave it a name, a halo, and a voice. The rest of us simply try to keep up—with our syllables gasping behind us.

The scroll with an audible stress mark.

Some meters walk, others march.

Sprung Rhythm?

It vaults over history, stumbles into rhyme, and lands gloriously off-balance—exactly where poetry belongs.

A syllable short, but never out of rhythm.

A line broken, but never without music.

A poet listening to the wild heartbeat beneath every word.

Sprung Rhythm Today

When Poetry Refused to March and Decided to Groove Instead

Sprung Rhythm didn’t disappear.

It simply unbuttoned its collar, slipped out of its Victorian cassock, and wandered into slam poetry lounges, indie song lyrics, and breathy spoken-word monologues with no punctuation and way too much emotion.

Hopkins gave it a name.

Nursery rhymes gave it mischief.

Limericks gave it comedy.

And the 21st century?

It gave it a mic.

Today, you can hear Sprung Rhythm’s heartbeat in places Hopkins never imagined:

In the offbeat pauses of a jazz poem.

In the uneven breath of a performance poet declaring love like a grenade.

In rap lyrics that ignore the line break but never miss the beat.

In literary rebellion disguised as free verse with internal structure.

Sprung Rhythm didn’t die. It simply went undercover.

It hides in the natural cadence of thought, where no two sentences fall the same—just like no two dappled things shine alike.

And whenever a poem leaps instead of walks, whenever a line stumbles into beauty, whenever a reader says, “Wait—was that allowed?”—

That’s Sprung Rhythm.

Still springing.

Still singing.

Still refusing to sit still.

ABS folds the scroll with a rhythm only the heart can scan.

Poetry, after all, is not what follows the rules.

It’s what makes rules look up, startled—

and listen.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Scholar

A line unsprung, but never silent.

A voice bouncing somewhere between thunder and kittens.

A scroll, and a smile, and a boom.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance