How Romantic visions transformed prose — shaping stories, essays, and Gothic imaginings that continue to haunt and inspire the modern world.

From The Professor's Desk

he Prose Turn: From Poetic Lyricism to Narrative Depth

If poetry was the heart of Romanticism, prose soon became its voice — deeper, more spacious, more capable of exploring the tangled inner rooms of the human soul. The Younger Romantics had burned their brilliance into the odes and stanzas of an age; now the prose writers stepped forward to carry that flame into new territories — through the winding corridors of fiction, the sharp clarity of essays, and the haunted shadows of the Gothic imagination.

It was not merely a change of medium. It was a deepening of Romanticism’s ambition — an acknowledgment that the lyric could sing, but the narrative could endure. The poet’s cry might capture a moment; the storyteller’s voice could weave a lasting myth.

And the times demanded new myths. Europe, in the wake of Napoleon’s fall, was a continent of broken promises and unquiet dreams. The Gothic castle, long a relic of literary fancy, became an emblem of the haunted modern mind — filled not only with literal ghosts, but with the restless spectres of unfulfilled ideals, social anxieties, and the ever-present fear that progress might come at too great a cost.

It was in this richly shadowed landscape that the Romantic spirit found new avatars — writers who took the emotional intensity, the philosophical daring, and the deep subjectivity of Romantic poetry, and re-forged them in prose.

Through Gothic novels, they gave voice to the unconscious and the sublime. Through essays, they taught readers to see literature not as moral lesson, but as a living, breathing art. Through fiction, they explored the vast inner terrains that the poets had only glimpsed in metaphor.

That timeless truth, whispered by the poets, now echoed through the halls of prose — in the haunted laboratory of Victor Frankenstein, in the drawing rooms of Austen’s heroines, in the solitary reflections of Lamb and Hazlitt, in the moonlit ruins and storm-lashed moors of Gothic fiction.

The Romantic prose writers did not replace the poets. They carried the movement forward — widening its reach, deepening its shadows, and giving it new forms in which to dream.

It is their story — their prose turn — to which we now turn the page.

The Prose Turn: From Poetic Lyricism to Narrative Depth

The shift from poetry to prose within the Romantic movement was not a retreat, nor a loss of lyrical spirit. It was an evolution — a widening of the form, a deeper descent into the labyrinth of human experience. For the Romantics, the age of the solitary poet beneath the open sky remained vital; but increasingly, that sky darkened with the weight of modern anxieties. The poet’s solitary song began to find its counterpart in the story, the essay, the novel — forms better suited to exploring not only fleeting beauty but the enduring complexities of self, society, and the shadows of the human mind.

Poetry had been the Romantic’s first weapon — sharp, swift, and dazzling. But as the nineteenth century progressed, there emerged a hunger for narrative depth — for works that could capture the shifting play of time, memory, and moral uncertainty. The lyric’s compressed moment gave way to the slow unfolding of a tale, to the reflective meander of the essay, to the architectural elegance of the novel.

This transition was not accidental. It was born from the very currents that had defined the Romantic spirit. The Gothic imagination, so central to the aesthetic of the Younger Romantics, had already shown how fiction could embody the era’s deepest preoccupations — its fascination with ruin, madness, the supernatural, and the tragic weight of history.

As Napoleonic Europe settled into a brittle new conservatism, and as the Industrial Revolution began to reshape the rhythms of life, Romantic writers felt a pressing need to explore the new realities confronting them. The Gothic castle, the haunted forest, the decaying abbey — these were no longer mere stage props. They had become symbols of the fractured modern psyche — of a world where progress and loss walked hand in hand.

In this charged atmosphere, Romantic prose flourished.

Mary Shelley, Jane Austen, Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt, and the great figures of Gothic fiction each took the Romantic impulse into new terrain. They brought to prose the qualities that had defined the poetry of the movement: emotional intensity, philosophical depth, a belief in the primacy of imagination, and an unflinching gaze upon both beauty and darkness.

They also brought something new: a growing awareness that the self is not merely a lyrical presence but a narrative construct — shaped by history, by society, by the buried tensions of memory and desire. The prose of the Romantic age is suffused with this awareness. In it, we find the beginnings of the modern exploration of identity — not as a static essence, but as a shifting, conflicted story we tell ourselves and others.

Moreover, Romantic prose brought to the foreground the question of genre itself. The boundaries between fiction and philosophy, between criticism and art, began to blur. The Gothic novel became a space where psychological truths were explored through supernatural metaphor. The familiar domestic novel of manners — as in Austen’s hands — revealed the hidden dramas of emotion and social constraint beneath everyday life. The personal essay, transformed by Lamb and Hazlitt, became a form of confessional art, where the self was both subject and lens.

The movement of Romanticism into prose was, at heart, an enactment of this truth. The longing that had animated the poets found new voice in the sprawling paragraphs of fiction and the sharply etched lines of the essay. The suffering and loss of an age that had seen the failure of revolutions and the rise of industrial modernity demanded new forms of expression — forms that could hold not only the moment of beauty, but the narrative of endurance.

And in this act of creation, the Romantic prose writers did not abandon poetry’s spirit. They carried it forward — into the haunted laboratories of Mary Shelley, the drawing rooms of Jane Austen, the refined melancholy of Charles Lamb, the impassioned polemics of Hazlitt, and the storm-lit towers of Gothic fiction.

In prose, Romanticism found its second breath — deeper, darker, more expansive. It is to these writers — and to the forms they shaped — that we now turn.

Mary Shelley and the Birth of the Modern Myth

When Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, she was just eighteen years old — a young woman whose life had already been steeped in tragedy, intellectual radicalism, and the shadowy allure of the Romantic imagination. And yet, in that act of creation, she gave birth not only to a novel but to a modern myth — a story that would haunt literature, art, and popular culture for more than two centuries.

The road to Frankenstein began, fittingly, on a night of Gothic atmosphere that could have come from the pages of her own book. In the summer of 1816, known as the Year Without a Summer, a group of exiles gathered at the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva: Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Godwin (not yet married to Shelley), Claire Clairmont, and John Polidori. The volcanic eruption of Mount Tambora had darkened the skies of Europe, lending an eerie, ash-grey pall to the season.

Trapped indoors by storm and gloom, the party took to reading German ghost stories. Byron issued a challenge: each guest should write a tale of the supernatural. It was this challenge — a game among friends — that gave rise to Frankenstein.

But Mary’s novel was no mere imitation of Gothic convention. Beneath its thrilling surface — the laboratories, the lightning, the monstrous creation — lies a profound meditation on the very themes that animated the Romantic imagination: creation, alienation, hubris, loss, and the eternal tension between nature and science.

Mary Shelley was born into a world of ideas. Her father was William Godwin, radical philosopher and political thinker; her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, one of the earliest and most courageous advocates for women’s rights. Wollstonecraft died shortly after giving birth to Mary, leaving a void that would haunt her daughter’s life and writing. The longing for an absent mother, the shadow of death intertwined with birth, would find powerful echoes in Frankenstein.

As a young woman, Mary fell in love with Percy Bysshe Shelley, a poet as brilliant as he was reckless. Their union brought exile, poverty, and frequent grief — not least the loss of their first child. Against this backdrop of romantic idealism and personal tragedy, Mary’s creative powers were honed.

“I busied myself to think of a story — one which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature and awaken thrilling horror — one to make the reader dread to look round…”

With these words, Mary Shelley later described her vision for Frankenstein. But in truth, her novel achieved much more. It was not simply a tale of horror, but a meditation on what it means to be human — and what it means to be other.

Victor Frankenstein’s act of creating life — of playing Prometheus — embodies the Romantic anxiety about the rising power of scientific reason divorced from ethical responsibility. The creature, abandoned and reviled, mirrors the Romantic outsider — alone, longing for connection, cursed by the very force that gave him life.

“I am malicious because I am miserable. Am I not shunned and hated by all mankind?”

In these words, the creature articulates not only his own plight but that of every Romantic exile — from Byron’s heroes to Shelley’s Prometheus to Keats’s solitary nightingale.

The genius of Mary Shelley lies in her ability to weave the personal, the philosophical, and the Gothic into a narrative that remains startlingly modern. In Frankenstein, the hubris of unchecked ambition, the isolation of the misunderstood, and the moral ambiguity of progress are explored with a depth rare in her time — or in any.

Moreover, Mary Shelley’s achievement must be seen in the context of a literary world still dominated by men. To write such a novel at eighteen, to outlast her husband and Byron, to continue writing and editing despite profound personal losses, marks Mary as one of the true founders of the modern literary imagination.

Frankenstein endures because it speaks to timeless anxieties. In an age obsessed with technological power, with artificial intelligence, with the ethical frontiers of genetic engineering, Mary Shelley’s vision is more relevant than ever. The creature’s anguished plea for understanding, for love, for a place in the human story, resonates across the centuries.

“I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel…”

Thus speaks the voice of Romantic longing in its purest, most tragic form. And in giving that voice to a nameless, reviled creation, Mary Shelley not only transformed the Gothic novel — she transformed the very possibilities of prose fiction.

In her hands, the Romantic ideal of the haunted self became the engine of a modern myth. And through Frankenstein, that myth continues to pulse in the bloodstream of literature — as vital, as unsettling, as unkillable as the creature itself.

Jane Austen: Romance, Reason, and the Domestic Mirror

To place Jane Austen within the Romantic movement is to understand that not all Romantics wandered storm-lashed cliffs or invoked the West Wind. Some worked their magic in quieter rooms — with a sharper eye, a surer pen, and a deep understanding that the wars of the heart are no less profound than those of empire or imagination.

If Byron, Shelley, and Keats were poets of the sublime and the storm, Austen was the chronicler of the drawing room, the parish walk, the ballroom glance — and in these spaces, she uncovered the profound dramas of character, class, and conscience.

Born in 1775, Austen came of age as the first wave of Romanticism was taking shape. The winds of revolution blew across the Channel; the works of Wordsworth and Coleridge were beginning to change the poetic landscape. Yet Austen’s world remained deeply rooted in the structures of English society — a society of inheritance, manners, and the complex negotiations of marriage.

It is tempting to see Austen as standing apart from Romanticism — her style restrained, her tone ironic, her subjects domestic. Yet to do so is to misunderstand both Austen and Romanticism itself. The true Romantic spirit was not confined to lyric ecstasies and Gothic ruins. It was a spirit that sought to elevate the individual experience, to explore the depths of feeling, to challenge the false pieties of society. In this, Austen was a Romantic of the highest order.

Her novels — from Pride and Prejudice to Emma to Persuasion — are rich with the Romantic tension between feeling and reason, between the claims of the heart and the expectations of the world. Austen understood that the true battleground of the soul often lies not in the wilds of Nature, but in the drawing rooms and dining tables where social conventions wage silent war upon authentic emotion.

“There is no charm equal to tenderness of heart.”

In these words from Emma, we hear the core of Austen’s Romantic sensibility — a belief that feeling, rightly guided, is the highest of human virtues. But Austen’s genius lay in her refusal to surrender entirely to passion. She understood that without the tempering force of reason and self-knowledge, the Romantic impulse could lead to folly or ruin.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Sense and Sensibility, a novel that pits the Romantic Marianne Dashwood, all fire and spontaneity, against her sister Elinor, whose outward composure masks a deeply Romantic capacity for emotional depth tempered by moral strength. In the arc of Marianne’s painful education, Austen offers a profound meditation on the dangers of unchecked Romantic idealism.

Yet Austen was no enemy of the Gothic imagination. In Northanger Abbey, she reveals both her affection for and her sharp wit regarding the Gothic craze that swept through late 18th- and early 19th-century England. The young heroine, Catherine Morland, intoxicated by the lurid charms of Ann Radcliffe’s novels, imagines dark conspiracies where none exist — a playful commentary on the power of imagination and its capacity both to enrich and distort reality.

“If adventures will not befall a young lady in her own village, she must seek them abroad.”

With this wry observation, Austen nods to the same longing that animates the poetry of Keats and Shelley — the hunger for adventure, for meaning beyond the ordinary. Yet she reminds us, too, that true growth lies not in Gothic fantasy but in the clear-eyed acceptance of life’s complexities.

Austen’s mastery lies in her ability to reveal the emotional richness of the seemingly ordinary. Her heroines undergo journeys no less profound than those of Byron’s doomed heroes or Shelley’s cosmic visionaries — journeys toward self-knowledge, moral integrity, and the courageous embrace of authentic love.

In doing so, Austen quietly subverted the very society she portrayed. Her novels expose the mercenary nature of marriage markets, the limitations imposed upon women, and the moral hypocrisies of her age. Without ever preaching, Austen taught her readers to value sincerity, kindness, and the steadfast pursuit of truth in a world rife with artifice.

And if Romanticism sought to awaken the soul’s deepest yearnings, Austen’s work reminds us that such yearnings are often most keenly felt in the small gestures, the unspoken glances, the moments where restraint gives way to revelation.

“You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.”

In that iconic declaration from Pride and Prejudice, we hear not only Darcy’s voice but the heartbeat of the entire Romantic spirit — a spirit that insists, even amid the constraints of society, upon the primacy of feeling and the redemptive power of love.

Thus, Austen stands not apart from the Romantic movement, but at its very heart — her prose a mirror in which we see the movement’s great themes reflected in the subtle play of manners, morality, and the human heart.

Charles Lamb and William Hazlitt: The Romantic Essayists

In an age when the great Romantic poets were crafting their odes and epics, another quieter revolution was taking place — in the humble essay. What had long been a form reserved for argument, didacticism, or dry moral reflection became, in the hands of Charles Lamb and William Hazlitt, an art of intimate voice, of personal reflection, of literary reverie.

Where the Romantic poets had expanded the scope of lyric subjectivity, these essayists did the same for prose. They taught readers that the self — in its moods, its memories, its contradictions — was a subject worthy of literary exploration. In doing so, they helped forge a path that would lead to the modern personal essay, the confessional memoir, even the reflective prose of today’s finest writers.

Charles Lamb — gentle, melancholic, deeply human — transformed the essay into a space where the soul could speak in prose. Writing under the pseudonym Elia, Lamb composed essays that shimmer with both wistful charm and profound pathos.

“The past is not dead. It lives in us, and will live in the future which we are now helping to make.”

In this line, as in so many of his reflections, Lamb embodied the Romantic belief that memory is not a prison but a wellspring — that the moments of our lives, though fleeting, can be preserved and transfigured in art. His essays often dwell on the small pleasures and quiet sorrows of existence — the texture of old books, the rituals of childhood, the bittersweet ache of lost friendship.

“Old familiar faces,” he called them — and in doing so, he elevated the ordinary to the level of the poetic. Lamb’s prose is itself a kind of prose poetry — not in rhythm or form, but in its sensitivity to emotional nuance and spiritual resonance.

Yet beneath the charm lies a life marked by deep personal tragedy. Lamb spent much of his life caring for his sister Mary, who, in a fit of madness, had killed their mother. The burden of this sorrow gave Lamb’s writing its unique tone — a blend of gentleness and unspoken grief, a voice that acknowledges life’s darkness even as it celebrates its fleeting joys.

In contrast, William Hazlitt brought to the essay a more fiery, more polemical spirit. A critic, philosopher, and political radical, Hazlitt wrote with a passion that reflected the idealism and frustration of the post-revolutionary age.

“The love of liberty is the love of others; the love of power is the love of ourselves.”

Hazlitt’s essays burn with a fierce commitment to truth and freedom. He attacked cant and hypocrisy wherever he found them — in politics, in society, even in literature. Yet he was no mere polemicist. His finest essays reveal a deep appreciation for art, imagination, and the complexities of human nature.

“To think is to act,” Hazlitt wrote — and his essays embody this credo. Whether reflecting on the nature of gusto in painting, the genius of Shakespeare, or the pleasures of journeying on foot, Hazlitt approached each subject with a mind both analytical and passionate.

If Lamb’s prose was a meditation on memory and feeling, Hazlitt’s was an enactment of the thinking self — restless, questioning, alive with intellectual energy. Together, these two figures expanded the essay into a form capable of expressing the full range of the Romantic spirit.

Through their work, the essay became a space where personal experience could be examined with the same depth and nuance as poetry — where the self was not a fixed entity, but a shifting landscape of impressions, ideas, and emotions.

Moreover, they demonstrated that prose could achieve the same lyrical beauty and philosophical resonance as verse. In their hands, the essay became a mirror in which the Romantic concern with selfhood, imagination, and the transience of life was vividly reflected.

“We long. We suffer. We love. We lose. We create.”

This pulse of the Romantic heart beats as strongly in Lamb’s tender recollections as in Hazlitt’s impassioned critiques. Their essays remind us that the ordinary self, in all its contradictions and yearnings, is a fit subject for the highest art.

And in doing so, they ensured that Romanticism would not remain confined to poetry alone — that its spirit would breathe through the supple sentences of prose, finding new life in every thoughtful reader who turns the page.

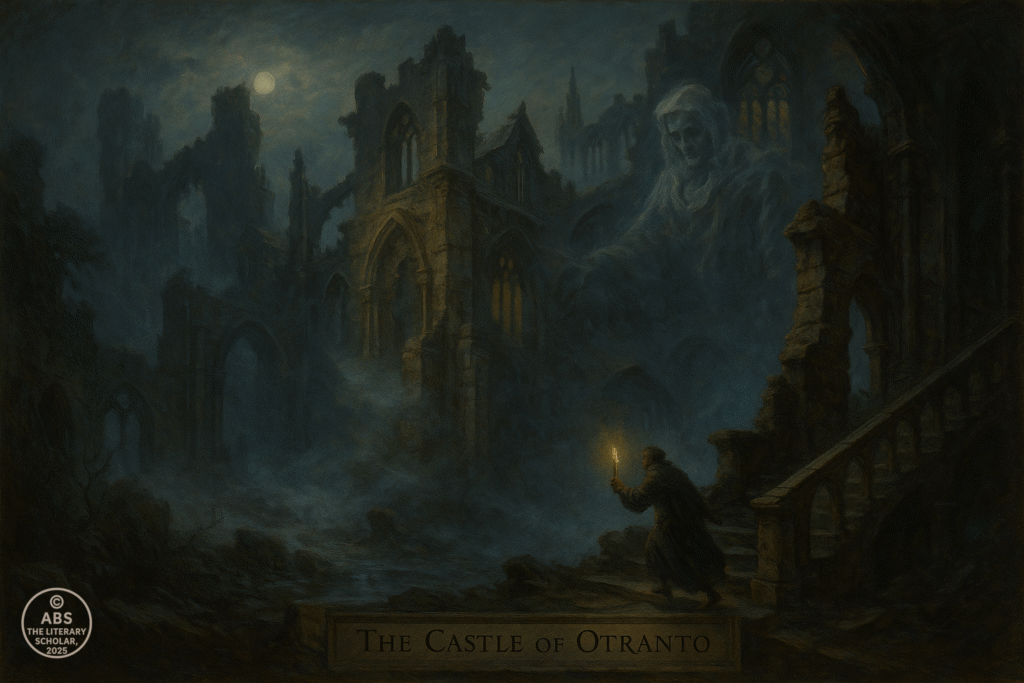

The Gothic Imagination: Castles, Ghosts, and Dark Longings

If Romanticism taught us that the human heart is a chamber of strange and shadowed rooms, then Gothic literature threw wide the doors and dared to wander within. The Gothic was no mere sideline of the Romantic movement; it was one of its darkest and most enduring currents — a form through which the era explored its deepest anxieties and most forbidden longings.

Where the lyric ode reached upward toward beauty and truth, the Gothic novel descended into the crypts of the human psyche — unearthing the fears, desires, and primal terrors that more respectable art often sought to repress. In doing so, it gave the Romantic imagination one of its richest and most potent forms.

The Gothic had its roots in an earlier era — Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) is often cited as its first true flowering. Yet it was the Romantic age that brought the form to full bloom. Writers such as Ann Radcliffe, Matthew Lewis, Mary Shelley, and countless lesser-known figures transformed the Gothic into a literary phenomenon that both thrilled and unsettled readers across Europe.

But why this fascination with ruined castles, with wandering spectres, with mad monks and innocent heroines pursued through moonlit corridors? The answer lies not merely in taste, but in the very tensions that defined the Romantic era.

The late 18th and early 19th centuries were times of profound cultural dislocation. The collapse of feudal structures, the upheavals of revolution, the rapid onset of industrial modernity — all contributed to a collective sense that the past was not truly past, that beneath the thin veneer of Enlightenment reason lay a darker, older world of irrational forces.

The Gothic gave voice to this unease. Its crumbling castles were not merely settings; they were metaphors for the haunted modern self — structures that might appear strong but were riddled with hidden passageways, ancestral sins, and the looming presence of unresolved history.

Ann Radcliffe, perhaps the greatest Gothic novelist of the age, understood this perfectly. In works such as The Mysteries of Udolpho, she crafted narratives where the line between supernatural terror and psychological dread remained tantalizingly blurred. Her heroines moved through landscapes charged with sublime beauty and mortal danger, embodying the Romantic fascination with both Nature’s grandeur and human vulnerability.

“The passions are wrought up to a high degree of terror; but the reader is led to hope, and then almost to fear, that they may not be completely gratified.”

Radcliffe’s genius lay in her ability to sustain this tension — to suggest that the true Gothic terror lies not in the ghostly apparition, but in the mind’s capacity to imagine what it most fears.

In contrast, Matthew Lewis’s The Monk (1796) plunged unabashedly into sensational horror — with its lurid tales of seduction, incest, and diabolical pacts. Yet even in its extremity, Lewis’s novel reflects a Romantic preoccupation with repressed desire and the consequences of denying the body’s and spirit’s darker impulses.

And hovering above the entire Gothic landscape is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein — a novel that fuses the Gothic with the Romantic’s deepest philosophical concerns. Here, the ancient trope of the cursed creator finds new life in the modern Prometheus — a figure who, in seeking to transcend natural limits, unleashes forces he cannot control.

In Frankenstein, as in the Gothic more broadly, we see the Romantic anxiety that human ambition, unchecked by wisdom or compassion, may give birth to monsters. The laboratory becomes a new kind of Gothic castle; the creature, a modern ghost — a haunting embodiment of the age’s moral uncertainties.

Yet the Gothic’s significance extends beyond its plots and settings. In its exploration of fear, desire, and the sublime, the Gothic became a vehicle for expressing truths that the more decorous forms of the time could scarcely acknowledge.

It gave voice to:

In this sense, the Gothic is the shadow-self of Romanticism — its dark twin. Where the ode seeks harmony, the Gothic reveals the fractures; where the lyric exalts Nature, the Gothic reminds us that Nature can be indifferent, even hostile; where the essay celebrates reason, the Gothic whispers of madness.

Nowhere is this more painfully evident than in the Gothic vision — where longing leads to transgression, love turns to obsession, loss gives birth to haunting, and creation yields both beauty and horror.

The enduring power of the Gothic lies precisely in its refusal to offer easy resolutions. Its haunted corridors remain open, inviting us to confront what we most fear — and to acknowledge that those fears are, in part, of our own making.

Thus, as Romanticism moved beyond its poetic youth, the Gothic ensured that its darker truths would not be forgotten. In every ruined abbey, in every spectral figure, in every flickering candle within a vast and empty hall, we hear the Romantic imagination still at work — searching the shadows for meaning, and finding there a reflection of its own haunted soul.

Walter Scott and the Romantic Historical Novel

If the lyric poets of the Romantic age sought to capture the eternal moment, and the Gothic novelists explored the haunted present, then Walter Scott turned his gaze toward the living past — weaving the legends, battles, and passions of bygone eras into the rich tapestry of the historical novel.

It is no small claim to say that Scott invented a new literary form. While stories set in the past were nothing new, it was Scott who transformed such tales into a vehicle for the Romantic imagination — one that would not merely reconstruct the costumes and customs of earlier times, but evoke the spirit of an age, the moral complexities of its actors, the conflicted legacies of history itself.

Born in Edinburgh in 1771, Scott grew up steeped in the oral traditions and folk legends of Scotland — a land where myth and history intertwined, where the past was not dead but vibrantly present in song, story, and landscape. This early immersion in national memory would shape his literary vision.

Though trained in law, Scott’s passion was for literature and antiquarian research. His early success came as a poet — The Lay of the Last Minstrel, Marmion, and The Lady of the Lake — works that captured the chivalric romance and heroic melancholy of Scotland’s turbulent past.

Yet it was with the publication of Waverley in 1814 that Scott forever changed the course of fiction. Here, for the first time, a novel presented a richly imagined historical world in which real historical figures and fictional characters moved side by side — where personal destiny was inseparable from the grand currents of political upheaval and social change.

“Look back, and smile on perils past.”

Scott’s novels are animated by a profound historical consciousness. He understood that the past is not a static tableau, but a living force that shapes — and often haunts — the present. In works such as Rob Roy, Old Mortality, and The Heart of Midlothian, Scott explored the tensions between tradition and progress, between personal loyalty and national identity.

His greatest international success, Ivanhoe (1819), turned to medieval England, blending the chivalric ideals of romance with a clear-eyed view of social conflict — particularly in its portrayal of the divisions between Normans and Saxons, and its sympathetic depiction of the Jewish heroine Rebecca.

Through such works, Scott gave Romanticism a new dimension. Where the lyric poets sought communion with Nature or the sublime, Scott brought to life the epic of the nation — showing how individual lives are shaped by the forces of history, and how the past, with all its glories and tragedies, continues to live in the collective soul of a people.

“It is not by the gray of the hair that one knows the age of the heart.”

This quintessentially Romantic sentiment courses through Scott’s novels. His characters — whether rebels, monarchs, outlaws, or common folk — are not mere symbols of their time. They are flesh and blood, driven by passion, fear, loyalty, and longing. Through their stories, Scott explored the timeless truths that connect us to our ancestors — the ways in which human nature remains constant amid the flux of historical change.

In doing so, Scott also helped to forge the modern sense of cultural identity. His novels celebrated Scottish history and tradition, contributing to a revival of national pride at a time when Scotland’s distinctiveness within the British union was under strain.

Yet Scott’s vision was never narrowly nationalistic. He saw history as a realm of complex moral lessons, a record of both heroism and injustice. His novels invite readers to empathize with the past — not to romanticize it blindly, but to understand its human dimensions.

This refrain, so central to the Romantic imagination, pulses through Scott’s pages. His heroes and heroines long for justice, suffer loss, love with fierce devotion, lose all they hold dear, and yet — through the telling of their stories — create a lasting vision of the past that speaks to the present.

Scott’s influence was profound and enduring. Without him, the great historical novels of the Victorian age — from Dickens to Thackeray to George Eliot — would be unimaginable. The very concept of the novelist as historian, as cultural interpreter, owes much to his example.

In an age obsessed with progress, Scott reminded his readers that the past is never truly past — that the echoes of old battles, old loves, and old betrayals still shape the world we inhabit. And in doing so, he gave Romanticism a new and powerful form — one in which story and history are woven together, and in which the imagination becomes a bridge across the chasm of time.

The Legacy of Romantic Prose and Fiction

It is a mistake — though an understandable one — to think of Romanticism as the province of poets alone. If its early music rang most purely through the odes of Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, and Keats, the movement’s deeper current flowed steadily into the wider sea of prose — shaping not only how we tell stories, but how we imagine ourselves as feeling beings in a complex and changing world.

In the essays of Lamb and Hazlitt, in the novels of Austen, Mary Shelley, and Walter Scott, and in the Gothic imaginings of Radcliffe and her peers, Romanticism found new voices — voices capable of expressing truths that poetry alone could not contain. The lyric, after all, is the cry of the moment; prose, the slow unfolding of the mind and heart over time.

And it is in this act of creation through prose that the Romantic spirit has perhaps left its most enduring legacy. For in prose, the Romantic ideals of individual feeling, moral imagination, and the primacy of the inner life found room to breathe — to expand into the narrative spaces that would come to define modern literature.

The personal essay, born anew through Lamb and Hazlitt, became a form in which the self could speak directly — fragmentary, uncertain, deeply human. In their pages, we hear the first stirrings of the modern confessional voice, the acknowledgment that to write is to reveal not only wisdom but also frailty.

The Gothic novel, often dismissed as sensational or escapist, gave shape to the unspoken terrors of the age — and of every age since. It reminded readers that beneath the façade of civilization, beneath the bright Enlightenment faith in reason, there lie the shadows of the irrational, the repressed, the unconscious. In giving literary form to these shadows, Gothic fiction helped pave the way for the psychological realism of later fiction — and for our modern understanding of the self as a layered and often conflicted entity.

Through Mary Shelley, the Romantic prose tradition also engaged directly with the emerging forces of modernity — with science, technology, and the ethical dilemmas they entail. Frankenstein remains not merely a Gothic tale, but a foundational myth of the modern world — a meditation on creation, responsibility, and the terrible cost of seeking power without wisdom.

In Walter Scott’s historical novels, Romanticism gave birth to the idea of fiction as a means of cultural memory — as a bridge between the present and the past. His works remind us that to understand who we are, we must understand the stories that shaped us — and that the past is never a dead thing, but a living force in the present.

And in Jane Austen, the Romantic spirit found one of its subtlest and most enduring expressions — the belief that authentic feeling, tempered by reason and moral clarity, is the foundation of a life well lived. Her novels teach us that the Romantic quest is not confined to the wilderness or the battlefield, but is enacted daily in the drawing room, in the parlor, in the hidden chambers of the heart.

Together, these prose writers extended the reach of Romanticism beyond the realm of poetry — transforming it from a literary movement into a cultural and philosophical force that still shapes our literature, our films, our art, and our very sense of what it means to be human.

The legacy of Romantic prose is all around us. In every novel that foregrounds the inner life of its characters, in every essay that dares to explore the uncertainties of feeling, in every story that grapples with the tensions between progress and morality, the Romantic spirit whispers still.

“We long. We suffer. We love. We lose. We create.”

These words could serve as the epigraph to the entire Romantic tradition — and to the countless works of prose that continue to carry its torch.

For if the lyric ode gave Romanticism its voice, prose gave it its echo — an echo that, centuries later, still rings through the chambers of literature, urging us to listen, to feel, to imagine, and to create.

The story of Romanticism is not a closed book. Though the lives of its poets and prose writers faded into history, their words — and the questions they posed — remain urgently alive. To read their works is to enter a conversation that has no end, a dialogue between the heart and the mind, between the individual and the world, between the light of aspiration and the shadows of doubt.

In prose as in poetry, the Romantics taught us that to feel deeply is not a weakness but a strength; that to confront beauty and mortality with open eyes is the highest form of courage; that to explore the haunted chambers of the human spirit is an act of creation as vital as any song or sonnet.

And as we close this trilogy of scrolls, we carry forward their most enduring lesson:

“We long. We suffer. We love. We lose. We create.”

In this unending cycle, we find both the tragedy and the triumph of the human story — and the eternal reason why, across the centuries, the Romantic voice still calls to us through the written word.

The Professor folds this final scroll of the Romantic Era — where prose and poetry together wove the richest tapestry of longing and light. The echoes remain, soft as memory, sharp as truth.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance