By ABS, The Literary Scholar

(Who knows that sometimes literature doesn’t rescue you—it just sits beside your sorrow with quiet understanding)

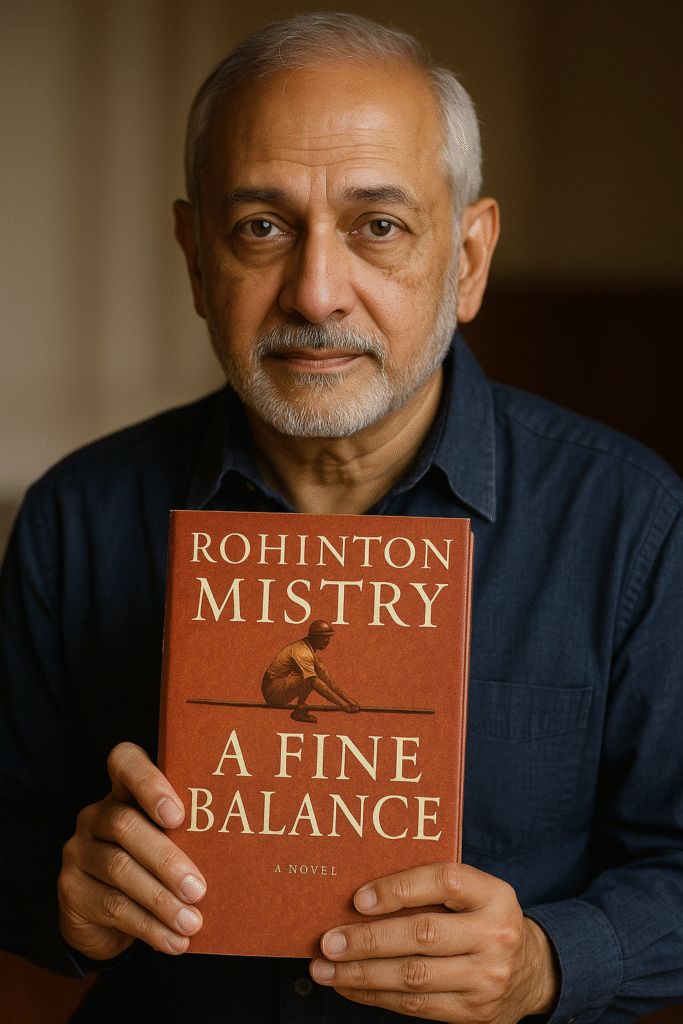

There are books you read. And then there are books that read you back, like a tailor measuring you for a suit you’ll never grow out of. Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance is one such literary tailor shop—cutting deep, hemming heartbreak, and threading quiet tragedy through every page.

Set against the backdrop of The Emergency in India (1975–77), where democracy took a suspicious little nap and returned wearing authoritarian pajamas, the novel doesn’t scream politics. It does something worse—it shows you what happens when power forgets people.

Four strangers. One cramped flat. An emergency sewing machine. And no exit plan.

Meet the Flatmates: Misery’s Misfit Quartet

Mistry throws together four of the most beautifully broken people in Indian fiction—not because they have chemistry, but because they have no choice.

Dina Dalal: A widow determined not to become her brother’s dependent, holding onto her independence with the ferocity of someone who has nothing else left. Sharp, proud, and clinging to her rented flat like it’s oxygen.

Ishvar and Omprakash Darji: Uncle and nephew. Tailors. Dalits. Survivors of caste-based carnage who stitch clothes for a living while trying to stitch their dignity back together. Spoiler: the country keeps cutting the thread.

Maneck Kohlah: A soft-spoken college student from the mountains, accidentally tossed into the flat-share from hell, idealistic enough to think he can major in Refrigeration and minor in Survival.

Together, they share one roof, two sewing machines, and several centuries of systemic oppression.

The Real Villain: Not Just The Emergency, But The Everyday

Yes, Indira Gandhi gets a few subtle jabs (never named, of course), and The Emergency looms like a dictator with a fondness for sterilization and censorship. But Mistry knows the truth: the worst kind of injustice isn’t the news-breaking kind. It’s the kind that drips, daily—in buses that don’t stop, queues that never move, police bribes, caste cruelties, and the landlord who sees your skin tone before your rent.

“You have to maintain a fine balance between hope and despair.”

That’s not advice. That’s a sentence.

Tailoring Through Tyranny: Stitch or Starve

Let’s talk about tailoring. In this novel, tailoring is everything. It’s livelihood, legacy, survival. Ishvar and Om flee caste violence in their village hoping urban tailoring will offer them escape.

And for a while, it does.

Until it doesn’t.

Because The State takes everything—jobs, homes, limbs, names. And when the government declares war on poverty, it sometimes forgets to warn the poor.

The tailors are rounded up. Forced into a labor camp. Sterilized—yes, sterilized, because family planning apparently required a few testicles and no consent. Then released, homeless, jobless, childless.

“Life’s hardest moments often resemble bureaucratic errors.”

Mistry doesn’t preach. He documents. And his documentation hits harder than any manifesto.

Dina: The Widow, The Warrior, The Woman on the Edge

Dina is not your textbook heroine. She doesn’t have a tragic backstory—she has a tragic present. Her spine, both metaphorically and literally, carries the novel.

She stands at the intersection of gender oppression and middle-class fragility, trying to be strong without appearing defiant, dignified without appearing difficult.

She resists charity. She resists her brother’s financial leash. She opens her home to strangers—not out of kindness, but necessity. And somewhere along the way, those strangers become family.

And like all literary families worth loving—they are torn apart.

Maneck: The Sensitive Boy Who Couldn’t Stay

Maneck is the reader’s conscience, quietly unraveling. Raised in the hills, dropped into the mess of Bombay, he observes more than he speaks. His friendship with the tailors is genuine, awkward, and incredibly touching.

He sees the decay. He sees the despair. But unlike the others, he doesn’t know how to metabolize it.

And in one of the most devastating time jumps in modern literature, Maneck returns years later—to find everything he loved reduced to dust.

“The city had become a graveyard of human intentions.”

He walks out.

And like every reader at that point—you don’t know whether to scream, cry, or close the book gently and whisper, “Why?”

The Ending: Not Tragedy, But Truth

Spoiler alert: There is no redemption arc. There is no social reformer bursting in with a last-minute policy change. There is no justice.

What there is… is a blind man selling monkeys, a stitched quilt of quiet memories, and two tailors living under a tree with smiles stitched tighter than their fate.

It’s not cynicism. It’s Mistry’s realism, which whispers that resilience is not always a political act. Sometimes it’s just enduring the day without bitterness.

And sometimes that’s the most revolutionary thing of all.

Somewhere near the last page, ABS, The Literary Scholar, folds the novel like a used ration card, rewinds the memory of Om’s laughter, irons out the wrinkles in Dina’s saree, and places a thimble over the part of the heart that still hurts.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

(Who knows that the emergency never really ended—it just updated its terms and conditions)

(Still stitches metaphors like Mistry’s tailors stitched trousers—with hope, precision, and unpaid overtime)

(And knows that “a fine balance” isn’t a resolution—it’s a form of resistance)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance