How Freud, Lacan, and the Inner Drama of the Mind Changed the Way We Read Stories, Symbols, and Silences

From The Professor's Desk

There’s a certain thrill in turning a page and realizing that the story knows you better than you know yourself.

It’s not just that Hamlet can’t act — it’s that he reminds you of all the times you couldn’t. It’s not just that Heathcliff is obsessive — it’s that part of you has lived (or longed for) that kind of madness. And when Gregor Samsa wakes up as a giant insect, the question isn’t why he’s a bug. It’s why you feel so much sympathy for him.

Enter: the subconscious.

In 1900, Sigmund Freud wrote a book that would make Victorian readers clutch their pearls and their pillows — The Interpretation of Dreams. But literature had already been dreaming, confessing, repressing, and projecting long before Freud gave those habits a name. What he offered wasn’t a new method of storytelling — it was a new way of reading the story behind the story.

“Literature is the royal road to the unconscious.” — paraphrasing Freud, with poetic license.

From ancient myths to modern novels, characters don’t just do things — they displace, they sublimate, they unravel. Every dagger has a double. Every ghost might be guilt. Every kiss might cover a crime.

Suddenly, the dusty old bookshelf turned into a therapy couch.

Freud’s influence arrived like a therapist in the middle of a family dinner — not invited, but impossible to ignore. The Oedipus complex wasn’t just about Greek tragedy anymore. It lurked behind Shakespearean hesitation, Victorian repression, and modern ennui. Literature, Freud argued, was less about what happened and more about why it needed to happen — what the story hid, forgot, or denied.

“Everywhere I go, I find a poet has been there before me.” — Sigmund Freud

Then came Jacques Lacan, the French theorist who took Freud’s couch and swapped it for a mirror. For Lacan, identity wasn’t something you were born with — it was something shattered and stitched together through language, longing, and reflection. Stories, then, became echoes of a fragmented self trying to make sense of a world that never quite speaks our language.

“The unconscious is structured like a language.” — Jacques Lacan

And so, literature became a puzzle of mirrors and masks. To read became to analyze — not just characters, but yourself. The trauma of a protagonist might mirror a national wound. A repressed desire in one scene might ripple through the entire plot. The narrator might be lying, but your own mind is likely complicit.

What started as a theory of dreams ended up decoding fiction, poetry, drama — and us.

This is not just the story of psychoanalysis. This is the story of how literature began to whisper what polite conversation repressed. How a slip of the pen revealed more than a page of explanation. How the human mind became the most haunted setting of all.

And so, dear reader — lie back. We’re going under.

The Mind Between the Lines – Introducing Psychoanalysis and Literature

Long before Freud sat on a couch and asked anyone about their mother, literature had already been busy spilling its dreams, suppressing its traumas, and projecting its secrets onto paper. Tragedies mourned too deeply. Comedies laughed too hard. Epics punished sins that no one could name. It’s almost as if literature had been waiting for psychoanalysis — not to write better stories, but to understand why it was writing them at all.

“We are what we repress,” Freud might have said, had he been a literary critic with a flair for aphorism.

When Sigmund Freud’s theories on the unconscious broke onto the scene in the early 20th century, they didn’t just revolutionize medicine — they turned literary criticism upside down. Suddenly, characters weren’t just acting, they were acting out. Plots became symptoms. Symbols weren’t decorative—they were diagnostic. And a good story? It was no longer about what the author meant, but what they couldn’t help revealing.

Literature: The Original Couch Case

To understand how literature opened its doors to psychoanalysis, we must first admit one thing: Literature has always been a little neurotic. It fixates. It repeats. It dreams in symbols. It obsesses over guilt, desire, power, and death. Shakespeare didn’t need Freud to understand that a man haunted by his father’s ghost might have unresolved issues. But Freud gave us a language to talk about it without calling the priest.

Take Hamlet, the poster child of overthinking. His delay in avenging his father’s murder has been called everything from strategic patience to poetic paralysis. Freud, however, pulled no punches — Hamlet, he claimed, cannot kill Claudius because Claudius has done what Hamlet secretly wants to do: remove the father and possess the mother. In one scandalous reading, Hamlet is less an avenger than a guilty voyeur of his own repressed fantasy.

“The play is built upon Hamlet’s hesitation over fulfilling the task of revenge that is assigned to him… it is the same hesitation that paralyzes all of us when the command to act exposes our inner desires.” — Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

In that moment, Hamlet stops being just a character and becomes a case study — and literature transforms from narrative to neurosis.

Freud’s Tool Kit: Dreams, Desires, Disguises

At the heart of Freud’s theory is the belief that the unconscious mind never sleeps — it merely disguises itself. Through dreams, slips of the tongue, jokes, and, yes, literature, the unconscious leaks its secrets.

He distinguished between two levels of content:

Manifest content – what the text (or dream) appears to say.

Latent content – what the text really wants to say, but is too afraid, ashamed, or polite to admit.

So, when a poem describes a tower, a critic might ask — is it really a tower? Or is it… something taller, darker, and symbolically male? A river may not just flow — it may repress. A forest might hide the id. A locked room? Don’t even get Freud started.

“A story is a daydream with footnotes.” — said no one in Vienna, but probably true.

Freud introduced mechanisms of repression, displacement, condensation, and sublimation — all of which became tools for literary critics to pry open texts. The idea was simple but radical: What if literature wasn’t about what the author knew, but what the author couldn’t know consciously?

Enter Oedipus: Tragedy as Diagnosis

Freud’s most infamous theory — the Oedipus complex — took its name from Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, a play in which a man unknowingly kills his father and marries his mother. Tragic, yes. But for Freud, it wasn’t just myth — it was metaphor for a universal psychological drama.

All children, he theorized, go through a stage where they unconsciously desire the parent of the opposite sex and resent the one of the same sex. Most outgrow it. Literature never does.

“Oedipus had to fulfill the curse not because he was guilty, but because he was human.” — the Freudian way of saying, “We all have mother issues.”

From this point forward, psychoanalytic readings of literature could point to nearly any text and whisper, “Oedipus.” Think of D.H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, or even The Godfather (Freud would’ve loved Vito and Michael). Stories became less about plot and more about buried family tension, repressed desire, and the return of the repressed — often at the worst possible moment.

The Text as Symptom

Freud didn’t stop at content — he looked at form. Why do stories loop? Why do they mirror? Why do characters contradict themselves or change without reason? For the psychoanalytic critic, these aren’t flaws — they’re symptoms.

A narrator who insists he’s sane (hello, Poe) is probably a prime suspect. A poem that keeps returning to the same image (plums, anyone?) is probably hiding an obsession. Even a happy ending might be a mask over unspoken trauma. Just like dreams, texts don’t lie — they leak.

From Classical to Contemporary — Literature’s Ongoing Therapy Session

Though Freud never claimed to be a literary scholar, his legacy in literature is undeniable. Writers like Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Franz Kafka internalized Freudian logic in their characters — streams of consciousness, fragmented memories, identity crises — all became literary equivalents of the therapeutic process.

“Reading became diagnosis. Writing became confession. And literature? One long talking cure.”

In short, Freud didn’t just read literature. He diagnosed it.

Freudian Keys to Fiction – Oedipus, Id-Ego-Superego, and Repression

If every great novel is a confession, then Freud gave us the keys to its locked diary. With the Oedipus complex, the id-ego-superego triad, and the machinery of repression, displacement, and sublimation, Freud didn’t just change how we interpret characters — he psychoanalyzed literature itself.

Let’s begin, appropriately, with the man who killed his father and married his mother — and made literary criticism blush for a century.

The Oedipus Complex: Tragedy with Parental Issues

Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex was already a Greek tragedy long before Freud came along. But when Freud looked at Oedipus, he didn’t just see a king undone by fate — he saw a psychic blueprint of every child’s internal drama. According to Freud, all children go through a developmental stage in which they harbor unconscious sexual desire for the opposite-sex parent and hostility toward the same-sex one.

Uncomfortable? Yes. Influential? Immensely.

“Oedipus’ destiny moves us only because it might have been ours.” – Sigmund Freud

In literature, this theory didn’t remain trapped in Thebes. It wandered into Danish castles (Hamlet), Yorkshire moors (Wuthering Heights), and even into 20th-century drawing rooms. Characters weren’t just dramatic — they were developmentally stuck.

Hamlet: The Prince Who Couldn’t

Freud’s reading of Hamlet is a masterstroke in psychoanalysis meets soliloquy. Why doesn’t Hamlet simply kill Claudius and move on with his royal life?

Because Claudius has done what Hamlet unconsciously wants to do: remove the father and possess the mother.

Gertrude becomes the silent axis of Hamlet’s psychological torment. The ghost isn’t just his father — it’s guilt. Hamlet delays not because he’s indecisive, but because acting would force him to confront the repressed desire he cannot admit.

“Thus the loathing which should drive him on to revenge is replaced by self-reproaches.” – Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

And so, the stage becomes the analyst’s couch — and the play, an unresolved case file.

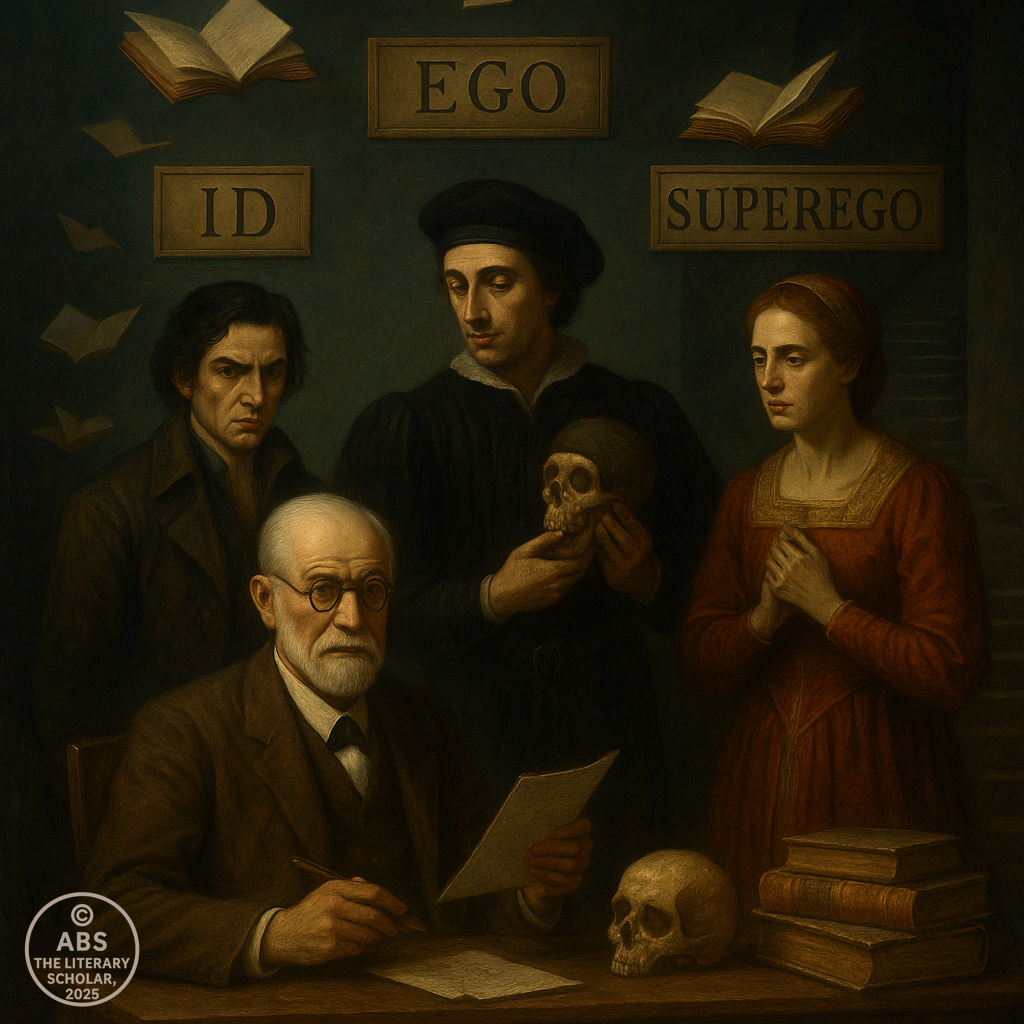

Id, Ego, and Superego: The Triangle Inside Us

Freud’s structural model of the psyche provided literature with a whole new cast of internal characters:

Id – primal, pleasure-seeking, instinctual (“I want.”)

Ego – the rational mediator (“Let’s be reasonable.”)

Superego – moral conscience (“You shouldn’t.”)

Characters in fiction often mirror this inner war.

🔹 Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights is almost pure id — violent, obsessive, irrationally driven by desire and revenge.

🔹 Jane Eyre negotiates between id and superego throughout her story, with the ego eventually choosing self-respect over reckless passion.

🔹 Lady Macbeth begins in alignment with the id (ambition, murder), but once the superego awakens (guilt, remorse), she unravels.

“I am in blood / Stepp’d in so far that, should I wade no more, / Returning were as tedious as go o’er.” – Macbeth

This is not just Macbeth talking — it’s his ego, exhausted by the endless shuttle diplomacy between his ambition (id) and his conscience (superego).

Repression, Displacement, Sublimation: Literature’s Favorite Games

Freud loved verbs that characters perform without knowing it:

Repression – Burying disturbing desires deep in the unconscious.

Displacement – Redirecting emotion from its real target to something safer.

Sublimation – Channeling socially unacceptable impulses into acceptable or even creative activities.

Let’s apply these to literature:

In Wuthering Heights, Catherine represses her primal love for Heathcliff, marrying the dull Edgar Linton instead. That repression comes back to haunt everyone — literally.

🕯 In Frankenstein, Victor sublimates his narcissistic god complex by creating life in a lab. The result? A monster — and a lot of Gothic guilt.

⚔ In A Streetcar Named Desire, Stanley displaces his insecurity about class and masculinity into violent control over Blanche. She, in turn, sublimates her guilt into fantasy — and then madness.

“The unconscious is not just a place of fear; it’s a place of fiction.”

Case Study: Lady Macbeth – Repression Wears a Nightgown

Lady Macbeth begins her story by weaponizing ambition. She calls on the spirits to “unsex” her, abandons morality, and orchestrates murder with military precision.

But then — the superego strikes back.

Sleepwalking, she rubs her hands obsessively: “Out, damned spot!” The blood she cannot see is the truth she cannot unsee. Her guilt has migrated from her mind to her body. Freud would call it a return of the repressed.

She doesn’t die from ambition. She dies from psychic collapse — a victim not of Shakespeare’s plot, but of Freud’s diagram.

Why This Still Matters

Freudian theory is no longer the emperor of psychology — but in literature, his reign is eternal. Every unreliable narrator, every haunted protagonist, every family drama filled with unspoken tension owes a nod to the Freudian lens.

Yes, the theory is controversial. Yes, it’s been challenged and expanded. But as a way of reading literature’s emotional core, it remains unmatched.

“Even if Freud were wrong, he’d still be right in literature.” – An honest critic, with a repressed need to analyze everything.

Lacan’s Language Games – The Mirror Stage, Desire, and the Symbolic Order

If Freud was the strict Viennese father of psychoanalysis, then Jacques Lacan was its rebellious, language-obsessed French son — the one who arrived late to the dinner party, broke the cutlery, and insisted that everything was just a metaphor anyway.

Where Freud gave us dreams, desires, and repression, Lacan gave us mirrors, metaphors, and misrecognition. He didn’t just reinterpret Freud — he turned psychoanalysis into a literary theory in disguise, dragging linguistics, structuralism, and Saussurean signifiers into the analyst’s chair.

“The unconscious is structured like a language.” — Jacques Lacan, with a flourish and a cigarette

It was no longer enough to ask what a character wants. Lacan urged us to ask: Who is doing the wanting? Through what mirror is that desire reflected? And what symbolic chains are holding that character — and the reader — hostage?

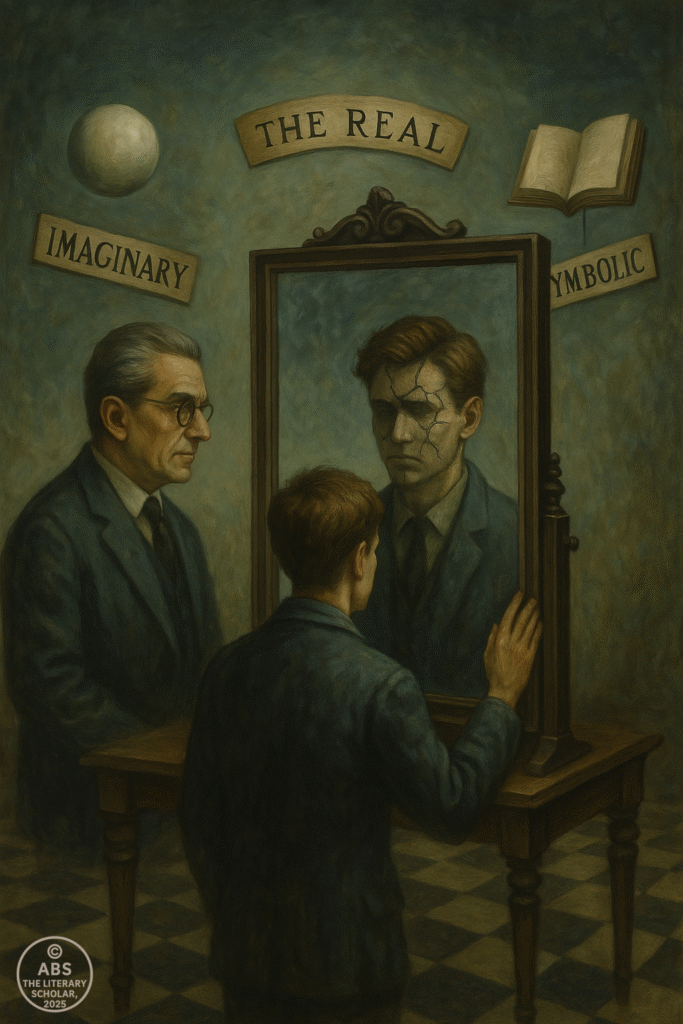

The Mirror Stage: Who’s That in the Reflection?

Lacan’s theory of the Mirror Stage is as elegant as it is unsettling.

At around 6–18 months, a child first sees itself in a mirror and recognizes — or rather, misrecognizes — the image as “self.” But this self is a fantasy: unified, whole, and stable. Internally, the child is fragmented, chaotic, full of uncoordinated impulses. Yet the mirror shows a beautiful fiction.

Thus begins the lifelong identity crisis.

“I am not who I think I am. I am who I see — and that’s the problem.”

In literature, this plays out whenever characters chase an idealized version of themselves — or crumble when confronted with their fragmented truth. Think of:

Jay Gatsby: Forever chasing the green light of his mirror self.

Frankenstein’s creature: Seeing himself through society’s rejection.

Blanche DuBois: Draping mirrors and fantasies to survive her psychic shatter.

Characters often mistake their projected self for their real one — a Lacanian drama in three acts.

The Real, The Imaginary, and The Symbolic: Literature’s Inner Architecture

Lacan divided human experience into three interwoven realms:

The Imaginary – The realm of images, illusions, and the mirror.

Literature thrives here: fantasy, metaphor, idealization.

It’s where the character sees what they want to be.

The Symbolic – The domain of language, culture, law, and structure.

The moment we enter language, we enter rules — society, identity, morality.

In fiction: the rules of the story, the family name, the father figure.

The Real – That which resists symbolization. It cannot be spoken.

In literature, it’s the moment when words fail. Trauma. Death. Raw fear.

Think: “The horror, the horror.” (Heart of Darkness)

“The Real is what lies outside the reach of fiction — but haunts every word of it.”

Characters trapped in these three realms ricochet between fantasy, social roles, and existential breakdowns. And so do readers.

Language and Desire: Talking in Circles

Lacan, steeped in Saussurean linguistics, believed that language doesn’t reflect the world — it creates it. And our desires are structured through that language.

We do not desire things. We desire what the Other (society, the father, the mirror) tells us to desire. Desire becomes a chain of substitutions — a never-ending game of signifiers chasing what Lacan called the “objet petit a” — the unattainable object of desire.

“Desire is a sentence we never finish.”

In fiction, this is why the hero never gets what they want. Or why they get it and still feel empty. Literature becomes Lacan’s playground — every line of dialogue, a symptom of displacement. Every metaphor, a veiled yearning. Every “I love you,” a misfire.

Literature as Lacanian Speech

To read literature through Lacan is to accept that meaning slips, stutters, and dances just out of reach. Characters speak, but the truth is in the gaps, the silences, the repetition.

In Virginia Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness, the symbolic order collapses — language leaks thought.

In Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, the Real looms — Godot never comes because language can’t summon him.

In The Bell Jar, Esther Greenwood’s psyche fractures under symbolic pressure — the father, the institution, the name.

“Every novel is a language system with a trauma beneath it.”

Even authors are trapped. They write, thinking they are in control — but Lacan would smirk and say: “It is the language that speaks, not the author.”

Lacan’s Legacy in Literature

While Freud dug into the content of literature, Lacan dissected the structure. He taught us to look at how language operates, how identity fractures, how desire deceives.

Lacanian criticism has influenced postmodernism, feminist theory, trauma studies, and deconstruction. But more than that, it gave literature a new terrain: the inner theatre of speech, mirrors, and masks.

“Characters speak in riddles because they live in one.”

Lacan didn’t want us to solve literature. He wanted us to get lost in it — to hear the echoes of our own fragmentation within the story’s syntax.

Reading Dreams, Fantasies, and Repressions – Psychoanalysis Today

Psychoanalysis, once the rebellious child of medicine and myth, has grown up — or at least moved out. In today’s literary world, Freud’s legacy lingers like an old ghost in a modern novel: not always invited, but never completely absent. And while the couch has become symbolic, and the cigar is now (ironically) a metaphor, the tools of psychoanalysis have evolved — expanding beyond repression and mother-fixations into feminism, trauma, memory, and postmodern fragmentation.

Because literature still dreams. It still forgets. And it still desperately wants what it can’t have.

Feminist Psychoanalysis: Reading Between the Patriarchal Lines

Enter Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray — thinkers who looked at Freud’s work and said, Interesting, but where are the women? Then they rewrote the entire playbook.

Julia Kristeva:

She argued that language itself — the very Symbolic Order Lacan loved — is patriarchal. And before we even speak, we experience a pre-linguistic, maternal space called the semiotic chora. In literature, this maternal rhythm erupts in poetic form, emotional cadence, and disruptive syntax.

“Poetry is where the mother tongue returns to haunt the father’s grammar.” — paraphrasing Kristeva with flair

Kristeva’s theories help us read The Bell Jar not just as a breakdown, but as a battle between oppressive language and unspoken emotional truth.

Luce Irigaray:

She challenged the Freudian binary altogether, questioning why female sexuality had to be defined through lack. Instead, she proposed a multiplicity — a feminine language of difference and excess.

“Woman is not a gap to be filled. She is a syntax waiting to be spoken differently.”

Feminist psychoanalysis doesn’t reject Freud — it rewires him. It takes his tools and builds new rooms in literature — ones where Ophelia, Sethe, or Esther Greenwood can speak in a tongue they were previously denied.

Trauma Theory: When the Repressed Returns With a Flashback

If Freud taught us that repression is personal, trauma theorists remind us that repression is also historical.

Literary trauma theory, influenced by figures like Cathy Caruth and Dominick LaCapra, explores how literature becomes a space where collective wounds resurface: wars, genocides, abuse, slavery. The mind cannot always articulate these experiences in real time — but literature can re-stage them, in fragments, symbols, and nightmares.

“Trauma is the Real knocking at fiction’s carefully painted door.”

Toni Morrison’s Beloved:

Sethe’s literal haunting is a metaphor for historical trauma — the ghost of slavery, memory, and maternal guilt. Sethe doesn’t just remember the past. She relives it.

Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar:

Esther’s breakdown isn’t just psychiatric — it’s a response to gendered social trauma, suffocating roles, and silenced emotions.

Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club:

A postmodern case of split subjectivity. The Narrator’s fractured identity is a modern echo of Freud’s divided self, updated with IKEA catalogs, masculinity crises, and soap made of liposuctioned fat. Sublime.

In each case, psychoanalysis helps us ask not what happened, but why it refuses to stay buried.

Critiquing Psychoanalysis: The Slip Beneath the Slip

Of course, psychoanalysis isn’t perfect — and neither are its interpretations. Modern criticism often accuses Freud of:

Over-sexualizing everything

Ignoring cultural and racial contexts

Reducing literature to diagnostic puzzles

And yet… it persists.

Because literature is full of slips. It does dream. And no matter how postmodern we get, stories still carry their traumas, displacements, and obsessions like vintage luggage.

“Even if psychoanalysis is outdated, our neuroses aren’t.”

What keeps psychoanalysis alive in literature isn’t that it explains everything — it’s that it keeps asking uncomfortable questions. It reveals that literature isn’t just about emotion. It’s written by it.

So Where Are We Now?

Psychoanalysis has now become plural — fractured into feminist, postcolonial, queer, trauma-informed forms. It’s less about diagnosis and more about interrogation: of power, identity, silence, and desire.

It teaches us that:

Stories are not whole.

Characters don’t always know themselves.

And sometimes, what isn’t said on the page matters more than what is.

“Literature is what happens when repression wears a tuxedo and trauma serves hors d’oeuvres.”

So let’s keep listening. Not just to what the characters say — but to what leaks out when they don’t.

To read literature through the lens of psychoanalysis is to eavesdrop on a text whispering its secrets — sometimes in dreams, sometimes in slips, and often in silences. From Freud’s couch to Lacan’s mirror, from Kristeva’s maternal rhythms to Morrison’s ghost-haunted past, the journey through desire, repression, memory, and language reminds us that fiction is never just a story — it’s a symptom.

Characters do not merely act. They unravel. They mourn, yearn, fracture, and forget. And behind each metaphor lies a deeper unease, a need unspoken, a wound unresolved. Psychoanalysis doesn’t always offer answers. But it teaches us how to listen — beneath the plot, behind the dialogue, inside the metaphor.

In this scroll, we have read with a therapist’s ear and a poet’s heart. Literature, after all, was dreaming long before Freud — and continues to dream long after.

ABS folds the scroll with care, placing it gently beside a jar of metaphors and a broken mirror. The couch is empty now, but the story remains — unfinished, unfiltered, unforgettable.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Professor

www.theliteraryscholar.com

Scroll Index: Explore Literary Theory Explained

(Click any to begin)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance