The Literary Rollercoaster with No Center, Only Play

From The Professor's Desk

The Age of Uncertainty Begins

There was a time—let’s say, mid-20th century—when we believed texts had stable meanings. Words behaved, authors ruled their pages like monarchs, and critics arrived with a magnifying glass and a firm belief in objective interpretation. That time is over.

Poststructuralism in literature begins precisely where structuralism begins to wobble. Where structuralism had laid out the promise of pattern and predictability—understanding stories through binary oppositions, mythic codes, and linguistic structures—poststructuralism pulled the rug from beneath it all. Suddenly, language wasn’t just unstable; it was treacherous. Meaning wasn’t revealed; it was constructed. And worst of all, your favorite novel? It might not mean what you thought it did. It might not “mean” anything at all.

At the heart of this movement is a philosophical suspicion. Suspicion of authority. Suspicion of permanence. Suspicion of certainty. Poststructuralists don’t aim to clarify—they aim to question. They read not to find a conclusion, but to explode the assumptions hidden beneath one. And it turns out, literature—especially the slippery, metaphor-laden, emotionally charged beast that it is—is the perfect site for this kind of rebellion.

We’re entering a world where there is no center, only play—of meanings, signs, perspectives. Welcome to poststructuralism in literature, where the author is missing, the reader is suspect, and the text just winked at you.

Why Begin with Poststructuralism?

ABS, the literary professor, reflects:

“This isn’t a theory for the faint-hearted. It’s for readers who enjoy getting lost, for students who dare to ask, ‘What if we’ve been reading everything wrong?’ Structuralism taught us how to recognize patterns; poststructuralism teaches us how to unsee them. That’s why this scroll comes next.”

Cracks in the Structure – When Systems Start to Slip

(From LIT Theory 002: Poststructuralism in Literature – The Literary Rollercoaster with No Center, Only Play)

Poststructuralism in Literature didn’t arrive with a bang—it arrived with a tremor. A hairline fracture in the confident architecture of structuralism, a gentle but persistent tug at the neatly drawn lines of meaning, order, and binary opposition. If Structuralism taught us to read literature like scientists dissecting fossils, Poststructuralism emerged like a slow earthquake—breaking the display glass and letting ambiguity leak in.

For a while, everything had seemed so beautifully logical. Signs and systems. Binaries and oppositions. Structures and stability. Structuralism promised order. But like all promises in literature, this one too came with footnotes, contradictions, and eventual collapse.

By the mid-20th century, thinkers and critics began to notice something peculiar: the very system that claimed to decode all stories was, in fact, just another story. A story that depended on silence, suppression, and a center it could never define. In other words, meaning itself was no longer stable—it was starting to wobble.

Literature: The New Playground of Uncertainty

In Poststructuralism in Literature, the first crack appeared when readers stopped asking what a work meant and began asking how it meant—and who gets to decide. Structuralist logic had made the reader a technician, trained to map recurring patterns. But those patterns, critics began to argue, were not universal—they were political, cultural, historical, and disturbingly Eurocentric.

Here’s where it all begins to unravel:

“The center is not the center.” — Jacques Derrida

If that line feels like a literary riddle, it is. But it’s also the intellectual heartbeat of poststructuralism. The idea that the very thing which anchors a system—its “center”—has no fixed identity. Meaning doesn’t flow from a divine source or an original author. It dances in deferral. It slips. It contradicts.

Why This Shift Matters

So, why does this shift matter in literary theory? Because once the floorboards of structuralism were pried loose, all sorts of creatures came crawling out—ambiguity, multiplicity, resistance, power, desire, politics, and the terrifying freedom to read without guardrails.

“To deconstruct the text is not to destroy it, but to open it up to unforeseen meanings.”

That’s the crux. Poststructuralism isn’t about burning down literature. It’s about refusing to build fences around it.

Enter the Professor

ABS, the literary professor, paused at the threshold of this intellectual tremor—not to run from the quake but to walk into it deliberately. For the readers trained in the safety of Structuralism, this new world might feel unmoored. But it is also liberating. A new kind of reading is on the horizon, and with it, a new kind of reader.

The Birth of Poststructuralism – Paris, 1966

It wasn’t a thunderclap. It wasn’t a revolution. It was a conference.

In October 1966, a group of intellectuals gathered at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore for a symposium titled The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man. What they unleashed, however, wasn’t just an academic talkfest. It was the beginning of what we now know as Poststructuralism in Literature—and like all great literary upheavals, it didn’t arrive with a manifesto, but with a whisper, a paradox, and a smirk.

Among the speakers was Jacques Derrida, a young French philosopher with a shock of dark hair and the demeanor of someone who knew he was quietly rearranging the intellectual furniture of the Western world. He delivered a paper titled Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences. What began as a polite lecture turned into philosophical TNT.

Derrida dropped a phrase that would echo for decades:

“The center is not the center.”

Suddenly, the whole house of structuralism trembled. Structuralism, which had neatly boxed language into systems of opposites and signs, was now being told that its center—its foundation—was an illusion. That every attempt to create stable meaning was doomed to fail because meaning was always deferred, always shifting, never present in full.

And thus, poststructuralism was born—not as a rejection of structuralism, but as its most mischievous child.

The Fall of the Center

To understand why this was radical, remember: structuralists had insisted on systems. They believed in the order of things—signs, signifiers, binary oppositions. Structure was safety. It meant predictability, clarity, elegance.

But Derrida argued that every structure has a center—and that this center paradoxically escapes the structure. The moment you try to define the center (God, Man, Reason, Author, etc.), you’ve imposed meaning from outside. And that, said Derrida, is cheating.

In other words, the moment you say, “This text means this because of this fixed point,” you’ve already lost the game.

Poststructuralism insists:

There is no fixed point. There is no master meaning. There is only endless play.

Or, in Derridean terms:

“Il n’y a pas de hors-texte.”

(There is nothing outside the text.)

Everything—culture, criticism, literature, identity—is a system of signs that reference other signs in a never-ending game of deferral. Language doesn’t lead you to truth. It leads you to more language.

The ‘Scene of Arrival’: Paris to Baltimore and Back

Though the term poststructuralism wasn’t used that day, the event catalyzed a shift. Derrida had lit the fuse. Soon, French thinkers like Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, Julia Kristeva, and Jean Baudrillard would dismantle what structuralism had built—one semiotic brick at a time.

The ideas weren’t contained to literature. They spilled into philosophy, psychoanalysis, history, art, sociology, architecture—even fashion. Suddenly, the world was being seen through lenses that questioned everything:

– Is meaning ever stable?

– Is authorship real?

– Can we trust language at all?

Poststructuralism as Intellectual Rebellion

If structuralism was about taming the text, poststructuralism let it run wild.

It embraced contradiction. It danced with ambiguity. It relished the instability that traditional theory tried to suppress.

This wasn’t merely an academic theory—it was a sensibility. A way of thinking that refused easy answers and called out every attempt at order as a performance. It said:

“Show me your truth, and I’ll show you your blind spot.”

Why ABS Begins Here

ABS, The Literary Professor, pauses here to explain why poststructuralism doesn’t simply follow structuralism—it unravels it with style. It doesn’t destroy meaning out of spite; it exposes the systems that claimed to own it. We begin here not with confusion, but with clarity about confusion.

“The text is not a puzzle to be solved. It is a game to be played.” — ABS, The Literary Professor

Poststructuralism isn’t here to help you understand literature—it’s here to teach you that literature is too clever to be understood only one way.

This is the second loop in the rollercoaster. Fasten your seatbelt.

Roland Barthes and the Death of the Author

Some revolutions don’t begin with riots—they begin with essays. In 1967, Roland Barthes slipped a literary grenade into the polite salon of structuralist thought, and it went off with a whisper: “The Author is dead.”

For centuries, readers bowed to the author like loyal subjects. If you had questions about a text, the answer lay in the writer’s life, intentions, diary, or deepest trauma. Meaning was seen as fixed—rooted in the sacred authority of the author’s voice.

But Barthes said non.

“The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author.”

With this radical line from his essay The Death of the Author, Barthes didn’t mean that novelists were to be exiled or executed. He meant that we must stop treating them as omniscient gods hovering over every sentence they’ve written. Once a text is out in the world, he argued, it belongs not to the author—but to the reader.

The Author, in his view, had become a tyrant of meaning. Readers, critics, and teachers routinely sought out what the author meant, treating the text like a coded message to be unlocked only by biographical clues. For Barthes, this approach was both limiting and naive. It treated literature like confession, not construction.

Instead, Barthes proposed a thrilling idea: meaning is not something given. It’s something made.

And it’s made by the reader.

The Reader as Creator

With the author dethroned, the reader suddenly became the main character. Literature turned into a space of interpretive freedom, not authorial control. A text no longer delivered one meaning—but many, based on who’s reading, when, where, and how.

As Barthes writes, “A text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination.”

In other words, the writer begins it—but the reader finishes it.

This was a seismic shift in literary theory. Imagine reading Jane Eyre not to figure out what Charlotte Brontë believed—but to explore what the novel does to you, how it opens meaning, how its form disrupts or reinforces cultural codes.

Barthes wasn’t just killing the Author—he was liberating the text. A book wasn’t a closed box with a single key. It was a weave of signs, open to multiple interpretations, each reading a fresh collaboration.

The Text as Tissue, Not Testament

In another of his essays, From Work to Text, Barthes described the literary text not as a monument—but as a tissue of quotations. Every phrase, every idea, he said, is pulled from a web of other texts, other voices, and other times. In that sense, the text becomes less about “expression” and more about interaction.

There is no pure originality. Every author is a reader, a recycler, a remixer. Even Shakespeare was cribbing off Plutarch and Holinshed.

So if the writer is already a reader, and the reader is now the meaning-maker, then where is the center? According to Barthes: everywhere and nowhere.

ABS Reflects

“You’re not just reading the novel. You’re co-writing it.”

—ABS, The Literary Scholar

ABS believes this is where literary study truly becomes alive. The classroom transforms from a lecture hall into a playground of ideas. Students are no longer note-takers of what the author ‘meant,’ but co-creators of what the text can mean.

Literature becomes less of a monument and more of a mirror—reflecting back not just a writer’s voice, but the reader’s curiosity.

The Death of the Author – Roland Barthes Returns

“The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author.” – Roland Barthes

Once upon a literary time, the author was God. Their words were law, their biography a map to meaning, and their intentions the final answer to every interpretative question. Teachers told students to “understand what the author meant.” Critics hunted for hidden meanings based on the writer’s life, their diaries, their letters, even their grocery lists. Literature was treated as a message in a bottle, and the writer’s mind was the ocean.

Then came Roland Barthes, with a dagger sharpened by semiotics and sarcasm.

In 1967, Barthes published his short but explosive essay The Death of the Author—a eulogy not for a real person, but for the very idea that an author should dominate a text’s meaning. In a world still basking in the afterglow of structuralism, where systems and structures were supreme, Barthes took a radical step further: he turned the system against its creator.

Why Barthes Had Enough of Author Worship

Barthes had long been suspicious of literary hierarchies. In his earlier Mythologies, he had dismantled everything from wrestling matches to wine labels using structuralist codes. But by the time he wrote The Death of the Author, his focus had shifted from how meaning is built to who gets to decide what a text means at all.

For Barthes, the author was no longer the divine architect of meaning but a shadowy figure whose presence limited the freedom of interpretation. If the author tells you what a story “really means,” then reading becomes passive obedience.

“To give a text an Author is to impose a limit on that text,” Barthes wrote, “to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing.”

In other words, the moment we let the author “speak for the text,” we stop listening to the text itself.

The Birth of the Reader: A Noisy Affair

Barthes flips the script entirely by placing the reader at the center of the interpretive process. The reader, he claims, is not just someone who absorbs meaning but someone who produces it.

In Barthes’s universe, each reader brings their own experiences, biases, knowledge, and emotions to the act of reading. The text becomes a playground of possibilities, not a prison of the author’s intent.

“A text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination.”

And that destination? You. The reader.

Example Time: Is That Banana Just a Banana?

Let’s say a poet writes:

The banana peeled slowly in the yellow sun.

Did they mean the ripening of colonial tensions? A sexual metaphor? Or just someone having breakfast? According to Barthes, it doesn’t matter what the poet meant. What matters is what you see, read, feel, interpret.

And if ten readers see ten different things? So be it. In fact, that’s the beauty of literature.

Literary Authority Becomes Literary Anarchy

Barthes’s theory shattered centuries of literary tradition. No longer was literature a one-way transmission from the author’s brain to the reader’s eyes. Instead, it became a two-way dialogue. Or better yet, a chaotic party where every reader brings their own music and refuses to go home.

This approach also democratized reading. You don’t need a PhD in a writer’s biography to engage with a text. You just need to read—and read actively, not reverently.

The canon was rattled. Criticism shifted. Classrooms changed. Suddenly, readers were asked not “What did the author mean?” but “What does this mean to you?”

But Wait—Is the Author Really Dead?

Critics have debated whether Barthes buried the author too soon. After all, isn’t it helpful to know that Orwell hated totalitarianism when reading 1984? Can we really ignore historical context? Or pretend authors don’t encode personal, political, or poetic meanings into their work?

Barthes wasn’t asking us to erase the author from existence—just to free the text from the tyranny of authorial intention. The author may have written the words, but once the book is in your hands, it’s yours to reimagine.

ABS, The Literary Professor, Leans In…

ABS, seated at the metaphorical professor’s desk, sighs dramatically and says:

“Barthes didn’t murder the author. He just took away their microphone.”

The author still exists. Their name is on the book, their voice on the page. But they no longer get to interrupt your reading and shout, “That’s not what I meant!”

ABS believes that this shift is what makes literature thrilling in the poststructuralist age. No longer is the reader an obedient student; they are now a co-creator. A rebel. A revisionist. A myth-breaker.

“Reading is no longer an archaeological dig for authorial bones—it’s jazz. Improvisational. Polyphonic. Alive.”

Michel Foucault – The Author as Function, Power as Text

There’s something poetic—and subversively French—about Michel Foucault sipping coffee in a turtleneck while casually dismantling the idea of the “Author.” Unlike Roland Barthes, who executed the author with one dazzling essay, Foucault didn’t just announce the death. He dug up the body, labeled it a cultural construct, and reburied it under institutional discourse.

Welcome to the world of “What is an Author?” (1969)—Foucault’s cryptic, brilliant, and relentlessly quotable contribution to poststructuralism. Where Barthes offered literary provocation, Foucault gave us philosophical provocation with footnotes.

The Author Was Never Alive. Just Useful.

Foucault didn’t merely ask what an author is—he asked why we care. Why does “Shakespeare” matter more than “Anonymous”? Why are some texts born with names (and respect) while others float nameless in literary purgatory?

According to Foucault, the author is not a source of meaning. Instead, the “author” is a function—a label society uses to control, categorize, and police meaning.

“The author is a certain functional principle by which, in our culture, one limits, excludes, and chooses.”

Translation: Authorship isn’t about creativity. It’s about control.

Power Wears a Cardigan and Teaches English

Foucault’s larger obsession was with power—not power as brute force, but as something that hides in institutions, systems, and ideas. And yes, literature.

Books are not innocent. Every text carries the weight of power—of what can be said, who is allowed to say it, and which ideas get canonized. For Foucault, literature is a site where discourses of authority play out.

A novel is never just a story. It’s a battlefield of voices: some loud, others silenced.

“Discourse is not simply that which translates struggles or systems of domination, but is the thing for which and by which there is struggle.”

That’s why Foucault’s theory is so thrilling (and intimidating). He doesn’t just change how we read novels—he makes us question why novels exist the way they do.

The Author Function: A Bureaucrat in the Library

Foucault’s “author-function” sounds like it belongs in a tax form. That’s intentional. He believed that our obsession with names—Barthes, Austen, Orwell—is less about inspiration and more about organizing knowledge. It’s easier to control a text when it has a name, a history, and a birth certificate.

Here’s the twist: not all texts require an author-function. For example, grocery lists don’t have authors. But Frankenstein does. Why? Because the literary market, academia, and copyright law want it that way.

Who’s Speaking? Who’s Silent?

This is where Foucault goes beyond Barthes. While Barthes plays with meaning, Foucault interrogates authority. Who gets to speak in a novel? Who’s left out? Why does Jane Austen get a literary throne while slave narratives sat in archives for centuries?

Poststructuralism, under Foucault, becomes political. It asks us to question the systems that elevate some voices and erase others. The “death of the author” is not a literary joke—it’s a revolution against literary gatekeeping.

Modern Application: Novels as Prisons and Playgrounds

Read The Handmaid’s Tale, and you’ll see Foucault in action. The Republic of Gilead is a structure of surveillance, regulation, and institutional language. Every word is weaponized. Every speaker is trapped in roles.

Or take Orwell’s 1984—a novel about language as domination. Newspeak is not just bad grammar. It’s power shaping truth.

These aren’t just dystopias. They’re Foucaultian playgrounds where power whispers from every sentence.

The Reader as Archaeologist

Foucault once called himself an archaeologist of knowledge. For literary scholars, this means we no longer read for the “author’s voice.” Instead, we dig into the layers beneath:

Who is allowed to speak in this text?

What institutional power shaped its narrative?

What voices are missing—and why?

Reading becomes excavation. The reader is not a fan of the author. The reader is a forensic theorist.

“The idea of the author is the ideological figure by which one marks the manner in which we fear the proliferation of meaning.”

We fear too much meaning. Foucault invites us to embrace it.

No More Pedestals, Just Perspectives

Thanks to Michel Foucault, the author no longer sits on a marble pedestal. They’ve been moved to a bureaucratic desk, surrounded by labels, systems, and historical baggage. And honestly? That’s liberating.

Now, literature becomes a site of resistance, subversion, and reinvention. The reader doesn’t just read the text—they read the world through the text.

The author isn’t dead. But their job description has definitely changed.

Julia Kristeva – Intertextuality and the Web of Meaning

Subtitle:

“Every book you read is haunted by the ones you haven’t.”

ABS Believes:

A literary text is not a sealed box—it’s a smuggler’s bag, bursting with echoes from every page ever written.

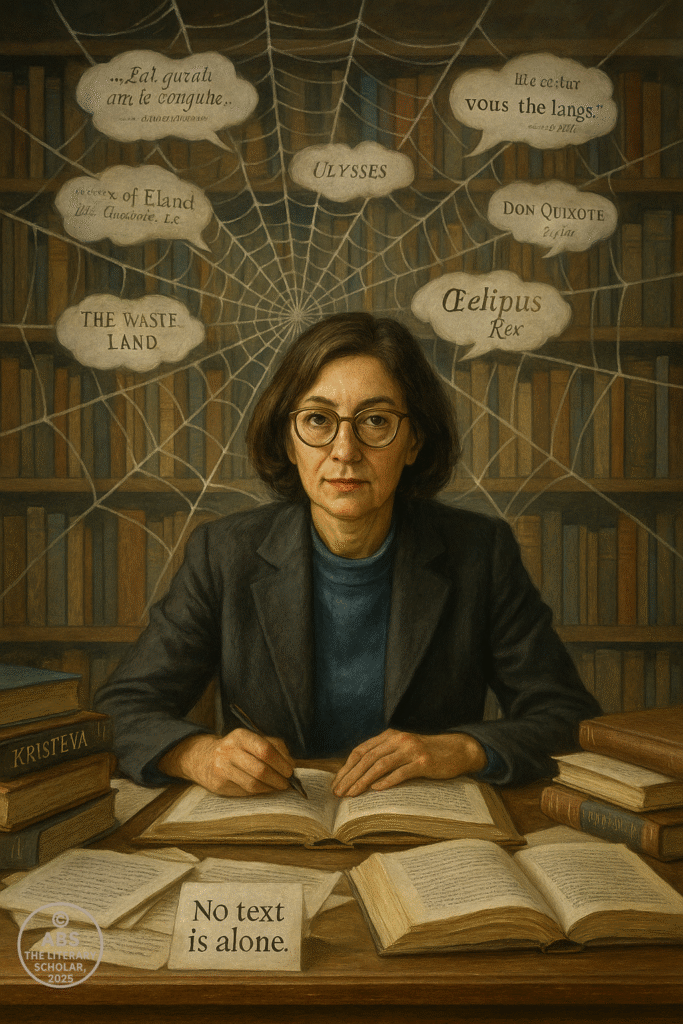

Once upon a literary time, texts were viewed as solemn monoliths—self-contained, author-certified, and gleaming with originality. Then came Julia Kristeva, linguistic rebel, psychoanalytic thinker, and poststructuralist par excellence, to whisper in our ears: There’s no such thing as a pure text. Every novel, poem, or essay is actually a densely layered tissue of citations, stitched together from countless other texts—some whispered, some shouted, some forgotten.

And just like that, the myth of originality got a footnote.

Intertextuality: The Web We’re All Caught In

Kristeva didn’t invent the idea of textual interdependence—Mikhail Bakhtin, the Russian theorist, had already explored dialogism and the idea that every utterance echoes others. But Kristeva gave it a name, a framework, and a literary swagger.

“Any text is constructed as a mosaic of quotations; any text is the absorption and transformation of another.”

—Julia Kristeva

In her landmark 1966 essay Word, Dialogue and Novel, Kristeva shattered the idea that we ever encounter a “pure” text. Instead, when we read, we’re decoding a network of influences—fragments from myths, pop culture, religious texts, advertisements, other books, overheard conversations, and linguistic clichés.

Yes, Virginia, even Shakespeare was remixing.

The Myth of Originality Dies in Footnotes

Originality, in Kristeva’s framework, is not about saying something new—it’s about how you arrange the borrowed. A novelist writing about love might echo Austen. Austen was echoing sensibility novels. Those novels were echoing classical tales. And so on, in an infinite loop of literary déjà vu.

This doesn’t mean writers are plagiarists. It means language itself is intertextual. The moment you write, you tap into a collective storehouse of meanings, metaphors, and structures that didn’t originate with you.

Poetry is not created in solitude—it’s a ghostly conversation across centuries.

The Waste Land: Kristeva’s Poster Child

If you’re wondering what intertextuality looks like, enter T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, the literary equivalent of a highbrow collage. Greek myth, Shakespeare, Buddhist scripture, Wagner, and nursery rhymes all crash into each other in five broken, brilliant sections.

“These fragments I have shored against my ruins,” Eliot writes—ironically predicting his future role in Poststructuralist classrooms.

Kristeva’s theory is practically printed in invisible ink on every page of Eliot. And Eliot, knowingly or not, becomes the perfect case study of a text that doesn’t “speak”—it echoes.

Intertextuality in the Age of Mashups and Memes

If Kristeva had lived long enough to witness Tumblr, fan fiction, and TikTok remixes, she might’ve simply nodded and said, “See?”

Intertextuality isn’t a lofty academic term anymore—it’s the air culture breathes. Consider how:

Bridget Jones’s Diary reframes Pride and Prejudice in 1990s London.

The Lion King borrows from Hamlet (with bonus warthogs).

Fan fiction rewrites endings, gender identities, and genres—all while loving the original.

Even memes—those bite-sized, captioned cultural artifacts—are pure intertext. One image spawns thousands of meanings depending on the text imposed over it. The format is fixed; the message is fluid.

Reading with Kristeva’s Eyes

To read intertextually is to stop pretending a book lives alone in its hardcover apartment. It’s to start seeing literary meaning as relational, contextual, and communal. When a poet uses a biblical allusion, a Homeric echo, or just drops in a Taylor Swift lyric—Kristeva is smiling somewhere.

“Text is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the ‘message’ of the Author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash.”

—Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text (Yes, Kristeva’s friend and co-conspirator).

Implications: The Reader as Literary DJ

If meaning is not created by the author, but by the reader recognizing echoes and allusions, then readers are like DJs—mixing beats, samples, and loops into their own version of the story.

Every reading becomes a re-writing.

When a reader says a novel reminds them of another book—that’s intertextuality.

When a student calls a poem “Shakespearean”—even if it wasn’t—that’s Kristeva’s theory in motion.

When you hear the phrase “winter is coming” and you don’t think of the weather—that’s the power of intertextuality in culture.

No Text Is an Island

Poststructuralism in Kristeva’s hands means this: meaning is made in the spaces between texts, not within them. Just as no word has meaning outside its context, no book breathes without its literary ancestors, cultural conditions, and responsive readers.

Literature is a web, and we’re all spiders pretending to be the first.

Kristeva doesn’t kill the author—she dissolves them in a literary acid bath of references. And the reader? They don’t just read; they trace. Like archaeologists brushing sand off a relic, they reveal layers of meaning older than the page they’re holding.

The next time someone tells you their novel is completely original, ask them if they’ve ever read Shakespeare, Homer, or Instagram captions. If they say yes—congratulations, Kristeva wins.

Jacques Lacan – The Decentered Subject

Subtitle: When Mirrors Lied and Language Took Over the Self

Series: Poststructuralism in Literature | LIT Theory 002

Poststructuralism in Literature: Losing the Self, One Reflection at a Time

By the time Jacques Lacan arrives on the scene, poststructuralism has already begun to pry open the sealed boxes of meaning, authorship, and originality. But Lacan wasn’t a literary theorist by trade — he was a psychoanalyst with a fondness for Freud, Saussure, and impossibly complex seminars. And yet, somehow, Lacan ends up becoming the favorite citation of every graduate student who wants to sound profound at parties.

His contribution to poststructuralism is nothing less than the decentering of the subject — the idea that you, dear reader, are not who you think you are. In Lacan’s world, the “self” is not a fixed, stable, authentic entity. Instead, it is a fragmented construction — stitched together by mirrors, language, desire, and a whole lot of misrecognition. Let’s unpack the madness.

The Mirror Stage: Where Narcissus Meets Neurosis

Lacan’s famous “Mirror Stage” posits that somewhere between 6 and 18 months, an infant catches a glimpse of themselves in a mirror. That moment of recognition — “Ah, that’s me!” — is also the moment of fundamental misrecognition. The child sees a whole, unified image, but internally feels fragmented. The mirror presents an illusion of cohesion, and the child buys into it. From here onward, we’re haunted by a desire to return to that illusory wholeness. Spoiler alert: we never do.

Lacan calls this moment the entry into the “Imaginary Order,” where the ego is formed — but it’s formed around a false image. It’s like living your whole life editing a selfie that isn’t you, hoping the world (and your inner child) buys it.

Literary Angle: In literature, characters often struggle with identity, illusion, and desire. Think of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, who constantly reflects (pun intended) on who he is, what he’s supposed to be, and why he can’t just act. Hamlet would’ve made an excellent Lacanian patient. He gazes at skulls, talks to ghosts, and spirals into existential despair — all the while trying to piece together a coherent “self.”

Language, the Unconscious, and the Slippery Signifier

Now comes the mind-bending part. Lacan famously said: “The unconscious is structured like a language.” What does that even mean?

It means that the deep, dark desires buried within us — the fears, fantasies, and neuroses — don’t exist as raw emotion. They’re structured, ordered, and expressed through language. And language, as Saussure taught us, is arbitrary. This means that our unconscious isn’t a pristine place of self-truth but a linguistically-coded labyrinth of misdirection.

In Lacan’s theory, we are born into the Symbolic Order — the realm of language, social law, and cultural meaning. Once we’re in it, we can never go back to the pre-linguistic Eden of unity (sorry, Imaginary Order). In the Symbolic, meaning constantly defers. Desire is produced not because we lack an object, but because language makes us lack it. We chase meanings, lovers, roles, and destinies we can never possess.

Desire, Lack, and the Endless Quest

Lacanian desire is not about fulfilling a need; it’s about the lack that structures our being. Desire is born not from what we want but from what we cannot have — the thing we believe will complete us, restore our lost wholeness.

This is central to many literary characters. Consider Jay Gatsby reaching for the green light — the fantasy of Daisy and the past he cannot recover. Or Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights, whose desire for Catherine borders on the metaphysical, because she represents something eternally out of reach. They’re chasing not just people but symbols of lost unity — Lacanian phantoms, if you will.

Literature: A Mirror of the Mirror

Lacan’s theories offer a brilliant lens through which to read literature:

Characters are often split between what they are and what they want to be.

Plots are driven by impossible desires and endless miscommunications.

Readers become participants in a drama of interpretation, bringing their own fragmented selves to texts filled with equally unstable signs.

Let’s return to Hamlet: his delay in avenging his father isn’t just procrastination — it’s an identity crisis. His ego is split. He cannot reconcile the public role of a son seeking revenge with the private self that questions everything. He lives in the Symbolic Order, but he yearns (impossibly) for Imaginary unity.

In Lacanian reading, texts become psychic battlegrounds. They’re not stable containers of meaning, but dynamic fields where language, desire, and the unconscious collide.

The Reader in the Text: A Haunted Encounter

Lacan also helped set the stage for Reader-Response Theory, which poststructuralists embraced later. Because if the self is already fractured, then reading — like identity — becomes a site of projection, misrecognition, and longing. Every time you read a novel and cry at a character’s pain, or see yourself in the villain’s trauma, you’re not discovering meaning. You’re creating it, through the fragmented mirror of your own psychic structures.

Lacan’s Labyrinth: Summary for the Brave

The self is not born whole. It’s constructed through images and misrecognitions.

Language shapes the unconscious. Our inner lives are scripted, not sacred.

Desire is endless. It’s not about having—it’s about lacking.

Literature reflects this fragmentation. It gives us characters and narratives as fractured as we are.

You don’t read Hamlet. Hamlet reads you.

ABS Reflects from the Other Side of the Mirror

Lacan’s theory doesn’t offer comfort. It doesn’t hug you and say, “You are enough.” It stares at you through the mirror and says, “You are lacking, and that’s what makes you human.” In a world obsessed with wholeness, certainty, and closure, Lacan insists that literature — like life — is better understood as a series of mirror tricks, flickering signs, and the eternal echo of the thing we almost had.

“Desire is a metonymy of being.” — Jacques Lacan

Or in ABS’s words: “You are not the narrator of your life. You’re a recurring metaphor in someone else’s sentence.”

Language Plays – From Sign to Sliding Signifiers

When Meaning Becomes a Game of Hide and Seek

ABS Believes: Meaning never really arrives—it pirouettes, hesitates, and leaves behind echoes we misread as conclusions.

This section explores how the foundational assumptions of language—once treated as fixed, logical, and referential—began to unravel in the poststructuralist imagination. We move from Saussure’s neat pairing of signifier and signified to Derrida’s chaotic carnival of signs: unstable, deferred, and endlessly self-referential.

The Fall of the Stable Word

There was a time when language was trusted like a loyal butler—reliable, efficient, and discreet. Say “tree,” and a tree appeared in your mind. Say “freedom,” and… well, at least you thought you knew what that meant. Structuralists like Ferdinand de Saussure helped us understand that the connection between a word (signifier) and its meaning (signified) was arbitrary but structured. The relationship worked because it was held together by a larger system of differences.

But then the poststructuralists arrived and stared long and hard at that neat diagram—and laughed.

They asked: What if there is no signified? What if the meaning just keeps shifting like sand under your feet?

Enter Jacques Derrida and the era of sliding signifiers.

The Play of the Signifier

Derrida’s term play (jeu) shook the philosophical world like a champagne cork in a seminar room. According to him, language doesn’t refer to fixed concepts—it refers to more language.

Meaning, therefore, is not delivered—it is deferred. This became the now-infamous concept of différance (deliberately misspelled with an “a” to highlight how meaning slips silently, even in spelling).

Every word leads to another word. You look up “justice,” and it sends you to “fairness,” then to “equality,” and suddenly you’re stuck in a dictionary loop, lost in an echo chamber of meaning. Words don’t point—they drift.

A Game of Meaningful Misunderstanding

In poststructuralism in literature, this linguistic slippage opens up delicious possibilities—and maddening uncertainties. Literary texts become sites of meaning production, not meaning delivery.

For example, in William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, time, voice, and narrative refuse to behave. Language loops, contradicts, and resists resolution. Is Benjy really dumb? Is Caddy’s shame real or constructed? Meaning is uncatchable—like a firefly that blinks just as you grasp it.

Or take Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot: a title that refers to someone who never arrives, in a play where words both fill the silence and deepen it. What does “Godot” mean? Nothing. Everything. Take your pick.

Puns, Paradoxes, and Shakespearean Chaos

Let’s not pretend that this linguistic dance is only modern. Shakespeare was already a poststructuralist prankster. Think of Hamlet: “Words, words, words.” Or King Lear: “Nothing will come of nothing.” Or Twelfth Night, where mistaken identities are created and sustained entirely through speech.

In poststructuralism in literature, these are not quirks—they are clues. Clues that language is not transparent but performative, contradictory, and gloriously unhinged.

Signifiers Without Anchors: Welcome to the Postmodern Jungle

By the time we reach postmodern literature, signifiers are not just sliding—they’re on a rollercoaster with no seatbelts.

Jean Baudrillard’s idea of simulacra ties in beautifully here. The signifier no longer represents reality—it replaces it. We consume signs of coffee (Starbucks logo), not coffee itself. In novels like Don DeLillo’s White Noise, entire lives are lived through slogans, TV voices, and advertising jingles.

The same goes for Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, where Oedipa Maas attempts to decode a conspiracy through signs and symbols—and ends up buried under them, like a detective crushed by her own evidence board.

From Meaning to Meanings—Plural, Unstable, and Joyfully Incomplete

In poststructural literary theory, then, a word is never just a word. It’s a performance. A betrayal. A wink across time.

Let’s say a character says, “I’m fine.”

Are they?

What if they’re not?

What if the phrase is ironic, defensive, or sarcastic?

In poststructuralism in literature, everything becomes suspect. The tone, the spacing, the context, the absence of context. A text is not a message—it’s a minefield. You, dear reader, are walking barefoot.

Literature as Linguistic Jazz

Structuralists gave us sheet music. Poststructuralists handed us a saxophone and said, “Improvise.”

Every time you read a sentence, you’re creating a new rhythm, a new variation. The “play” of language is not a malfunction—it’s the point. Literature becomes like jazz—what’s unsaid is as vital as what’s spoken.

So when Derrida says, “There is nothing outside the text,” don’t panic. He doesn’t mean that reality doesn’t exist. He means that once something enters language—whether a thought, a memory, or a sandwich—it becomes subject to all the distortions, delays, and delicious confusions of human speech.

Key Quote

“Language bears within itself the necessity of its own critique.”

— Jacques Derrida

Wrap-Up: How to Read in the Playground of Signs

So how do you read a text now?

Like a detective who doesn’t trust their own notebook.

Like a lover who knows words are always both sincere and manipulative.

Like a trickster, a translator, a traveller.

In poststructuralism in literature, language is no longer a ladder to truth—it’s a hall of mirrors. The question is no longer “What does it mean?” but “How is it making meaning now—and why?”

And if that sounds confusing, don’t worry. You’re doing it right.

Reading as Resistance – How Poststructuralists Read Texts

Postmodernism in Literature: When the Reader Fights Back

ABS Believes:

Reading is no longer passive consumption—it’s subversion, sabotage, and sometimes a stylish rebellion in literary disguise.

The Death of Meaning as a Literary Genre

In the comfy, old-fashioned world of traditional literary analysis, the critic’s job was quite respectable: identify the theme, trace the symbols, find the author’s intent, and tie it all up with a pretty conclusion bow. In this universe, meaning was assumed to be hidden but discoverable—like a treasure buried neatly beneath the surface.

But poststructuralism arrives with a crowbar, not a treasure map. And it’s here not to unearth meaning but to suggest that the entire idea of a single meaning is both laughable and oppressive. Reading becomes resistance: against authority, against closure, against being told what something “means.”

Where structuralism mapped the deep grammar of stories, poststructuralism attacks the assumption that those maps were ever trustworthy. And nowhere is this resistance clearer than in the poststructuralist approach to reading itself.

Forget the Author. Distrust the Narrator. Side-Eye the Text.

Poststructuralist reading is founded on suspicion—not of the text’s quality, but of its so-called stability. Readers trained in this mode don’t look at what the story says; they look at what it hides, contradicts, or refuses to admit.

Is the narrator too smooth? Too confident?

Poststructuralist readers call that an unreliable narrator—a literary PR agent covering up deeper narrative messes.

Does the text reach a neat resolution?

They’ll ask, “At what cost?” and dig into the moral, historical, or psychological debts being buried under that tidy ending.

Enter the Reader-Detective (Armed with Derrida)

Instead of a text being an object for interpretation, it becomes a battlefield of interpretation. Each reading becomes an act of resistance—a refusal to settle, a celebration of slippage, and a political statement.

Poststructuralist reading technique in action:

Imagine you’re reading a classic novel like Jane Eyre. The old-school reader says:

“This is a story about love overcoming class boundaries.”

The poststructuralist reader smirks and says:

“This is a story that pretends to be about love while erasing the racial trauma of Bertha Mason and encoding patriarchal surveillance inside Thornfield Hall.”

The text is no longer innocent. It’s been cross-examined and found suspect.

The Critic as Rebel, Not Guide

Earlier schools of literary criticism believed in interpreting the text for others—guiding students toward the “correct” meaning.

Poststructuralist readers reject that. To them, offering a single interpretation is an act of intellectual tyranny. The reader is not a translator of the author’s whispers but a co-creator in a noisy room of echoes, puns, references, half-meant meanings, and culture-laden assumptions.

Meaning is made in the act of reading. And that act is not gentle. It’s interrogative, sometimes even violent in its questioning.

Feminist and Postcolonial Theory: Resistance in Action

Poststructuralist reading opened the gates for newer theoretical movements to storm the literary canon with sharp questions:

Feminist critics began asking: “Why are women always muses, never authors of their destiny?”

Postcolonial theorists challenged texts that framed the West as reason and the East as chaos.

Queer theory found the absences, silences, and repressed desires that the heteronormative structure of language kept hidden.

Each of these reading styles is deeply poststructuralist—they assume that the surface of the text lies.

Poststructuralism in literature isn’t just about clever interpretations. It’s about justice. Identity. Power. Silence. Whose voice gets printed, and whose pain gets italicized for dramatic flair.

Case Studies: Deconstruction in the Wild

1. Shakespeare’s Hamlet

Not a tragedy of procrastination, but a text full of rhetorical spirals. Hamlet says, “Words, words, words,” because that’s all he has—and they keep failing him.

2. Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

Not a journey into savagery, but a narrative built on racist binaries that collapse under the weight of their own contradictions. Postcolonial readers take it apart, line by line, showing how meaning implodes.

3. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land

Not a modernist lament but a hyperlinked mash-up of stolen lines. The footnotes are a desperate attempt to control chaos—and the reader laughs because chaos is exactly the point.

In all these examples, reading is rebellion. It’s not a trip to find the author’s message but an archaeological dig to see how language constructs the world—and betrays it.

No Theme is Safe, No Symbol Sacred

Where earlier criticism revered the theme—a noble abstraction like “love,” “freedom,” or “identity”—poststructuralism sees it as a narrative prop.

Take the symbol of the “home.” To a structuralist, it’s a stable point in a story’s binary: home vs. away, safety vs. danger.

To a poststructuralist?

It’s a construct built by capitalist nostalgia and patriarchal exclusion, and it deserves to be demolished (with a literary wrecking ball).

Reading is Not a Luxury. It’s a Weapon.

Poststructuralism demands readers who are active, critical, aware of social context, and resistant to manipulation. It gives students permission to ask hard questions—and not be afraid of complicated answers.

It says:

📚 “You don’t have to agree with the book.”

🔍 “You don’t have to trust the narrator.”

🧠 “You don’t even have to like the author.”

You just have to read—deeply, suspiciously, and with a touch of elegant cynicism.

The Whispered Scroll

If you read a story and it lets you go easily,

read it again—this time with claws.

Let that deceptively simple tale feel the scratch of your suspicion.

Let the silences squeal.

Let the metaphors confess.

Literature is not a lullaby. It’s an interrogation room with velvet walls.

Because the stories that slip through your fingers too smoothly—

often hide their truths in the shadows of your comfort.

ABS’s Whisper for the Day

Where meaning plays hide and seek—

scratch beneath the words.

🪶 Signed,

ABS, The Literary Scholar

still marking margins where others see the end.

Multiplicity and the Fragmented Text

When Novels Became Labyrinths and Narrators Lost the Map

Postmodernism in literature

The Fragmentation Game

Once upon a time, a story had a beginning, middle, and end. It respected time, space, and the reader’s desire for closure. Then came postmodernism in literature—and it treated narrative like a jigsaw puzzle that arrives without the box cover.

Fragmentation isn’t just a literary style; it’s a worldview. If structuralists believed in systems and order, poststructuralists laughed politely and then handed over books like Borges’s The Garden of Forking Paths or Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. These texts don’t just tell stories—they question what stories even are.

The traditional arc? Gone. Instead: jump cuts, parallel plots, metafictional interjections, and self-aware narrators who may or may not exist.

Borges: The Librarian of Infinite Texts

Jorge Luis Borges is often called the “godfather of postmodern fiction,” and for good reason. In his short stories—if one dares to call them that—he creates infinite libraries (The Library of Babel), books that read the reader (The Book of Sand), and stories where endings circle back to the beginning.

Borges doesn’t write with plot as a compass; he writes with paradox as a candle. Meaning, in his universe, is both bottomless and precise. One sentence can contain an entire philosophy. One page can fold time.

Calvino’s Reader in a Narrative Hall of Mirrors

Italo Calvino takes things further in If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, a novel that is about a reader trying to read a novel titled If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. No, that’s not a typo. The book you are reading is about reading the book you are reading.

Every chapter begins a new novel, only to be cut short. Just as you’re invested, the page turns, the story disappears, and a new one begins. It’s narrative whiplash disguised as literary elegance.

Calvino’s postmodernism in literature doesn’t deny meaning—it multiplies it. The reader is not just a participant; they are the protagonist. The novel is not a linear journey—it’s a maze with witty signs and philosophical traps.

The Mirror Text: When the Story Watches You

In poststructuralist literature, the text isn’t a window; it’s a mirror. Authors such as John Fowles (The French Lieutenant’s Woman) interrupt their own storytelling to talk about the very act of storytelling. They confess their control. Or lack of it.

You’re reading a story—but suddenly, the author appears, shrugs, and says, “I could end this in three different ways. Here they are. You choose.”

This isn’t a narrative gimmick; it’s a philosophical stance. There is no authority. Only alternatives. No fixed meaning. Only interpretations. The author may be dead, but the reader has inherited an entire estate of possibilities.

Cortázar and Hopscotch Fiction

Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch is both a novel and a game. You can read it straight through—or hop between chapters in an order suggested at the beginning. Or, ignore both and invent your own path.

This radical non-linearity is postmodernism in literature at its most defiant. It says: “Why should reading be passive? Why must meaning arrive in order?”

The chaos is intentional. The gaps are instructive. The disorientation is part of the pleasure. Hopscotch doesn’t want to be consumed—it wants to be played.

A Mindset, Not Just a Style

Fragmented texts are not just about breaking chronology. They reflect the fragmented nature of identity, culture, and knowledge. In a world of infinite media, competing truths, and shifting ideologies, linear storytelling seems dishonest.

As Jean Baudrillard might say: in a world of simulation, continuity is the ultimate fiction.

Reader’s Toolbox: How to Read a Fragmented Text

To approach these poststructuralist marvels, drop your expectations of plot and purpose. Instead:

Look for patterns, echoes, repetitions.

Embrace confusion as a signal of complexity.

Read actively—highlight, question, interpret.

Accept that closure may never come. And that’s okay.

Reading these works is like following a breadcrumb trail that leads not to a cottage, but back to your own imagination.

The Literature of Disobedience

In the fragmented text, every rule is an invitation to rebel. These stories don’t apologize for being difficult. They dare you to find pleasure in uncertainty.

They are literary Rorschach tests. You see what you want to see. And that says something about you, not just the book.

Postmodernism in literature isn’t an era. It’s an attitude. It refuses to kneel before genre, chronology, or closure. It smiles, shuffles the chapters, and hands you a blank bookmark.

Ready to play?

Criticisms and Confusions — When Meaning Means Nothing

“Poststructuralism is like trying to nail jelly to a wall.”

— A frustrated student somewhere, probably.

So far, poststructuralism has gleefully torn apart the sacred cows of literary tradition—Author, Truth, Meaning, and the neat little line we once called “plot.” But even as it danced through Derridean wordplay and Barthesian mischief, poststructuralism began to earn itself a rather curious reputation: brilliant or bogus? Groundbreaking or gibberish? Empowering or exhausting?

This section takes a step back (or sideways, because what is linearity?) and turns the critique inward. When does playful ambiguity become pointless? When does liberation from meaning leave you… meaning-less?

Too Much Freedom?

Poststructuralism’s greatest gift—the idea that meaning is unstable and interpretation is endless—can also be its greatest curse.

If everything is a text, and every text is open to infinite interpretations, then who decides what’s meaningful anymore? Are we just throwing academic darts at a literary board blindfolded?

Terry Eagleton quipped, “Poststructuralism, for all its attack on authority, ended up enshrining the reader as a kind of god.” And if all readers are gods, does that make literature just a theological debate without any commandments?

Elitism in Jargon Cloaks

Let’s not pretend. Poststructuralism loves its vocabulary.

Différance (spelled wrong on purpose, thank you very much).

Discourse.

Hyperreality.

Intertextuality.

Decentering the center while centering the decentered subject.

If this sounds like a poetic tongue twister or the internal monologue of an overcaffeinated theorist—it probably is. Critics often complain that poststructuralist writing is deliberately obscure, designed to exclude the average reader. It’s not just what is being said, but how cryptically it’s said, that creates distance.

Some academics treat these texts like religious scripture—only the initiated may “understand” Derrida, Foucault, or Kristeva. This has led to accusations of intellectual elitism: theory as gatekeeping.

The Spiral of Infinite Interpretation

There’s an old poststructuralist joke (yes, they exist):

Reader: What does this poem mean?

Poststructuralist: Yes.

Poststructuralism invites you to challenge dominant readings, unpack hidden ideologies, and reconstruct meaning—but it often refuses to tell you where to stop. There’s always another interpretation lurking in the margins. In theory, this is thrilling. In practice, it can become paralyzing.

If everything is unstable, then can anything be said at all? Or are we just participating in the literary equivalent of echoing into a void?

Truth in Decline or a Shift in Power?

One of the loudest critiques is that poststructuralism leads to nihilism—a sense that nothing means anything anymore. When all truths are exposed as constructed, where does that leave ethics, politics, or even literature’s moral compass?

But let’s not underestimate poststructuralism. It doesn’t destroy meaning—it democratizes it.

Where once literature belonged to elites and scholars, poststructuralism hands interpretive power to feminists, postcolonial readers, queer theorists, cultural critics, and high school students annotating Hamlet with TikTok metaphors. Suddenly, your truth matters. And that is a revolution.

Examples of Interpretive Chaos

Take Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. In one classroom, it’s a critique of colonial brutality. In another, it’s accused of perpetuating racism. Which is right? Poststructuralism says: both. Or neither. Or maybe something else entirely, depending on your position.

Or Shakespeare’s Othello: Is Iago evil or just misunderstood? Is Desdemona a feminist figure or a patriarchal casualty? Poststructuralist reading says: Why not all of the above?

Literature becomes a hall of mirrors—what you see says more about you than the text.

ABS’s Compass in the Chaos

“If the theory’s slippery, maybe it’s because truth itself has buttered shoes.”

— ABS, The Literary Scholar

Poststructuralism teaches us that confusion isn’t failure—it’s intellectual honesty. The world isn’t neat, linear, or easily categorized. Literature shouldn’t be either.

Meaning is not a locked treasure chest to be broken open—it’s a kaleidoscope. Each twist shows something new. The trick is to stop expecting closure, and start enjoying the dizziness.

Poststructuralism may be accused of dodging clarity, but it opens up an urgent question:

What happens when we stop seeking the one truth, and instead begin listening to many voices in the text?

That, perhaps, is its deepest contribution—not a loss of meaning, but an explosion of it.

Scroll Index: Explore Literary Theory Explained

(Click any to begin)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance