Empire Writes Back—And the Center Can’t Handle It

From The Professor's Desk

There was a time when literature came wearing a powdered wig and spoke only in the accents of empire. Its maps were colored red, its characters were explorers and missionaries, and its readers were taught to see the world through the monocle of colonizers. This literature did not merely reflect the world—it helped define it, categorize it, conquer it. It built empires with metaphors and erased continents with silence.

But then the margins began to murmur. And eventually, they wrote back.

Postcolonialism in literature is not merely a reaction to empire—it is an unfolding literary consciousness, a refusal to let colonized people be seen only through the lens of the colonizer. It emerged from the shadows of imperial libraries and the wounds of history to reclaim language, land, and identity. It is, above all, literature that writes from the fracture.

The moment of decolonization did not simply mean political independence; it exposed the deeper colonization of culture, education, and the imagination. Colonized subjects were taught to read Shakespeare before they knew their own histories, to write essays in the tongue of the oppressor, and to view their own languages and customs as signs of backwardness. The result was a split self, a haunted identity caught between two worlds. And literature became the battleground where this struggle was most vividly fought.

“The Empire writes back to the centre,” declared a now-famous study in 1989, capturing in a phrase what so many writers from Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and the Middle East were already doing: reclaiming narrative power. Chinua Achebe did not just write a novel—he corrected Joseph Conrad. Salman Rushdie didn’t just create magic realism—he dismantled the logic of borders. Jean Rhys didn’t just tell a story—she gave voice to a madwoman silenced by Jane Eyre’s polite patriarchy.

To engage with postcolonialism in literature is to ask: Whose voice was silenced? Whose story was left untold? It is to realize that what often passed for “universal literature” was, in fact, provincial propaganda dressed up as humanism. It is to see the British canon not as a mountain peak of culture, but as a tower that cast long shadows over the rest of the world.

And yet postcolonial literature is not just literature of grievance. It is literature of reconstruction. It doesn’t simply expose the lies of empire—it builds alternative truths. It weaves hybridity, irony, orality, resistance, and exile into a new aesthetic fabric. It speaks many tongues at once. It walks between languages. It questions not only what was taken but what remains.

Today, postcolonialism in literature is as much about the past as it is about the present. It interrogates the aftershocks of colonization: cultural erasure, economic dependency, and the lingering politics of language. It explores the wounds of partition, the ghost of indenture, the violence of migration. And it reminds us that colonization did not end—it mutated. Into new empires. New silences. New narratives.

To read postcolonial texts is not just to empathize—it is to unlearn. To shift perspective. To feel the weight of history in syntax. And to listen, closely, when the margins no longer whisper—but command the page.

“The Empire Writes Back”: Introducing Postcolonialism in Literature

In the vast library of world literature, there was once a silence more resounding than speech—the absence of the colonized voice. For centuries, the novel, poem, or essay that spoke of colonized lands often came from the pens of those who arrived by ship, not those who belonged by birth. Colonialism, as it conquered lands and looted bodies, also claimed the right to represent reality. Literature was one of its most trusted emissaries. But eventually, history turned the page. And when it did, postcolonialism in literature was born—not as a decorative appendix to literary theory, but as a radical act of narrative reclamation.

The phrase “The Empire Writes Back” has, over the years, moved from being a clever inversion to a canonical declaration. Coined by Ashcroft, Griffiths, and Tiffin in their groundbreaking 1989 text, it signals the moment when the once-colonized began to speak—not in the master’s tongue, but on their own terms, using and subverting the language of empire. The term “postcolonialism” itself emerged as a multidisciplinary approach to understanding not just what colonization was, but what it left behind—culturally, psychologically, politically, and linguistically.

To understand postcolonialism in literature, one must first revisit the project of colonialism itself. Empires were not merely political machines; they were cultural projects. They exported language, imposed education, rewrote histories, renamed rivers, and categorized native populations with anthropological arrogance. Colonization sought not only to govern the body but to reshape the mind. The curriculum was as important as the courthouse. Macaulay’s infamous “Minute on Indian Education” (1835), in which he advocated for creating a class of Indians who were “English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect,” reveals the imperial strategy with brutal clarity: control the imagination, and you control the future.

And this is where literature entered, stage right, dressed as civilizer.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the British novel, for instance, became a subtle but powerful site of empire. Works like Jane Eyre, Kim, or Heart of Darkness are not just stories; they are texts that locate “civilization” in the metropole and “savagery” in the colonies. The colonized rarely had subjectivity; they were backdrop, danger, burden, or exotic spice. They were the other—the foil against which the Western self could feel enlightened, noble, and just.

But the 20th century brought both decolonization and disruption. Political independence movements—from India’s 1947 freedom to the dismantling of African colonial rule—brought a parallel cultural awakening. The postcolonial author did not simply emerge; they intervened. Writers like Chinua Achebe, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Aimé Césaire, Jean Rhys, Derek Walcott, and Arundhati Roy did not write to add diversity to global bookshelves—they wrote to correct a miswritten history.

Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) stands as a foundational text in this shift. It narrates the story of an Igbo village not from a colonial administrator’s diary but from within the cultural rhythms and linguistic cadences of the community itself. There is no need for a white interpreter; the voice has returned to the native. In doing so, the novel doesn’t just tell a story—it undoes a thousand previous ones.

Postcolonialism in literature also means confronting the afterlife of empire. For the end of colonial rule did not mean the end of colonial influence. Nations that once fought for independence found themselves entangled in neocolonial structures—economic dependency, imported political systems, and educational models that still privileged Western epistemologies. Literature became the space where these contradictions could breathe, bleed, and speak.

But postcolonialism is not a single, monolithic discourse. It is diverse, contested, and evolving. Caribbean postcolonial literature, for instance, might explore the legacy of slavery, creolization, and diaspora in ways very different from South Asian or African contexts. Writers like V.S. Naipaul or Salman Rushdie explore postcolonial identity through irony, fragmentation, and magical realism—tools that reflect the shattered but vivid reality of their histories.

Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981) famously uses the device of a narrator born at the exact moment of India’s independence, whose body begins to fall apart as the country’s political dreams do. Here, the body becomes the nation, and narrative becomes a battle over memory. Language itself becomes a playground and a battlefield. Rushdie bends English—not to mimic the Queen, but to decolonize it.

Equally important is the feminist and intersectional turn in postcolonial literature. Writers like Tsitsi Dangarembga (Nervous Conditions), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Half of a Yellow Sun), and Bapsi Sidhwa (Ice Candy Man) challenge the idea that postcolonial literature is only about nationhood or resistance. They bring gender, sexuality, religion, and class into the frame. After all, what good is national freedom if the private realm remains shackled?

Postcolonialism in literature is also deeply invested in the question of language. Should a postcolonial writer use English, French, or Portuguese—the language of the colonizer—or return to indigenous tongues? Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o famously abandoned English for Gikuyu, declaring that writing in the language of the oppressor perpetuates colonial logic. Others, like Achebe or Roy, have argued for writing back in English, using the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house. There is no single answer—only the ongoing tension of articulation.

Even now, in the 21st century, the postcolonial lens remains urgently relevant. As migration, globalization, and digital connectivity blur borders, colonial hierarchies reappear in new disguises—as publishing gatekeeping, cinematic stereotyping, or academic Eurocentrism. Postcolonial literature continues to trace these new asymmetries while celebrating the resilience of hybrid identities, the joy of recovered histories, and the wit of survival.

To introduce postcolonialism in literature, then, is not to enter a tidy room of theory. It is to enter a storm of voices—some angry, some lyrical, some whispering through forgotten pages. It is to hear the hum of resistance beneath rhyme, the echo of exile behind metaphor, the longing for home even when the land has changed forever.

And in that storm, if one listens closely, one realizes: the margin never needed permission to speak. It was always writing—scratching on the edge of the canon. Waiting not for empire to listen, but for empire to fall silent.

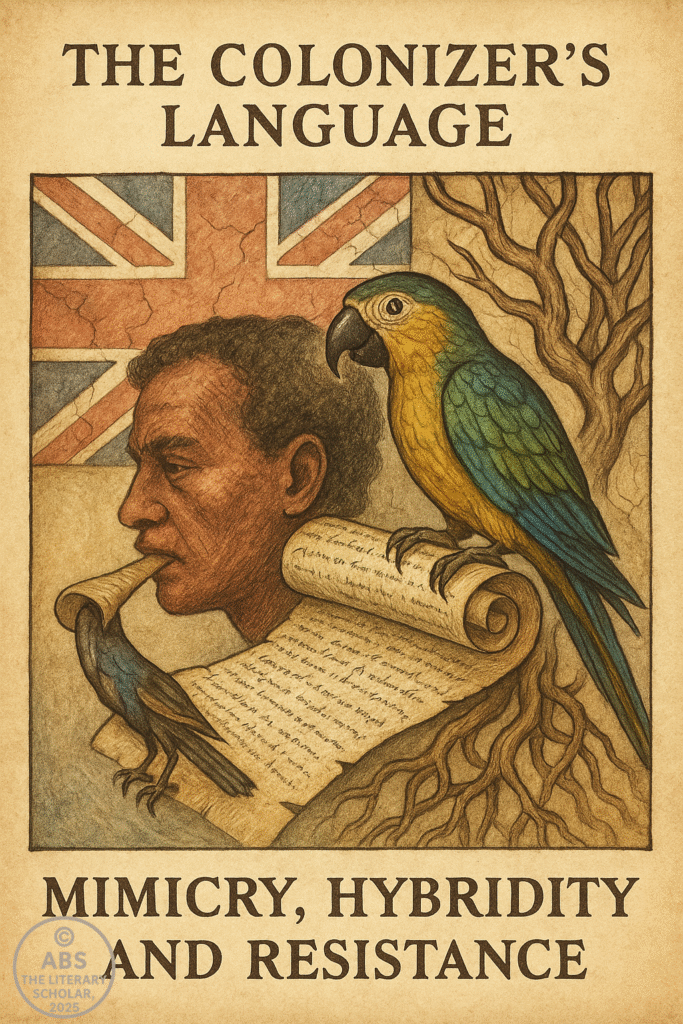

The Colonizer’s Language: Mimicry, Hybridity, and Resistance

Colonialism did not just invade land—it invaded language. It marched into the mind via the tongue, leaving not only flags and railways but also syllables, metaphors, dictionaries. And long after the colonizers packed up their treaties and trunks, the linguistic residues remained, stubborn and slippery. One of the most potent concerns in postcolonialism in literature is precisely this: What happens when you are forced to tell your story in the language of your oppressor?

The British Empire, like most imperial projects, weaponized language. It was not just a medium of communication—it was a medium of control. It taught the colonized how to write essays, sign contracts, compose prayers, and perform obedience. English became the passport to power, privilege, and survival. And yet, in that very act of linguistic violence, the empire planted the seeds of its own undoing.

Enter Homi Bhabha, a postcolonial thinker who refused to see colonized subjects as passive receptors of imperial influence. For Bhabha, the story was more nuanced. Colonized people did not simply imitate their rulers—they mimicked them. And mimicry, as Bhabha famously argued, is a slippery double gesture: it appears to flatter the colonizer, but in fact subtly mocks and destabilizes them.

“Almost the same, but not quite.”

This is mimicry: a strategy of partial presence, deliberate imperfection, colonial performance laced with ironic defiance. In literature, this is often seen in characters or narrators who speak the colonizer’s tongue but bend it, twist it, echo it with a smirk. From Achebe’s use of Igbo-inflected English in Things Fall Apart, to Salman Rushdie’s polyphonic, pun-saturated English in Midnight’s Children, postcolonial texts show us language not as a prison, but as a site of play, of power, of resistance.

But mimicry alone does not account for the strangeness of postcolonial language. For that, Bhabha offers us another concept: hybridity.

Unlike the colonial obsession with purity—racial, linguistic, cultural—hybridity revels in contamination. It is the third space, the in-between, where new meanings are born out of conflict. In this liminal zone, neither colonizer nor colonized has full authority. The colonizer loses the ability to fix meaning, and the colonized escapes the trap of being a mere echo. Hybridity is not just a mixture—it is a mutation.

Take, for example, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who chose to abandon English entirely and write in Gikuyu, asserting that language is not neutral—it is a carrier of worldview. But others, like Derek Walcott, preferred to stay within English, infecting it with Caribbean rhythms, oral textures, and the historical burden of sugar plantations and shipwrecks. In both cases, language becomes not just a medium but a theatre of rebellion.

“The English language is nobody’s special property. It is the property of the imagination.”

—Derek Walcott

This quote is not just a poetic flourish—it is a political stance. In postcolonialism in literature, the act of writing becomes an act of repossession. Writers do not ask for permission. They appropriate, distort, and remix. They turn the Queen’s English into a creole of fury, memory, and metaphor.

There’s irony here, of course. The colonized were once told that their native tongues were primitive, unsuitable for abstract thought or fine feeling. But now, those same tongues haunt English literature, like ghost notes in a symphony. Every postcolonial novel written in English is, in some sense, a palimpsest: beneath the polished sentences lies another rhythm, another syntax, another way of being.

This is why language in postcolonialism is not just about form—it is about identity. To write in English after empire is to perform a high-wire act: to speak with the master’s voice, but not for the master’s cause. It is a way to fracture meaning from within, to mock fluency, to insert pauses where clarity once reigned.

We see this most clearly in texts that combine tongues, break grammar rules, or collapse dialects—what some might call “broken English” is in fact a new literary dialect, born not out of incompetence but insurgency. From Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, authors mold English into new shapes, letting it wobble, weep, sing, and stammer. It is no longer the colonizer’s language—it is the colonized’s revenge.

And yet, this hybridity also comes with tension. It is not purely celebratory. Some postcolonial writers express a deep discomfort, even guilt, about using English—aware that every sentence might betray a deeper silencing. Others embrace it but feel constantly haunted by what cannot be translated, what is lost in adaptation. The ache of the unspoken—the untranslatable—is part of the postcolonial condition.

So what do we do with this paradox? Do we reject English entirely or embrace its mutation? Do we seek purity or play?

Postcolonialism in literature suggests we do neither. Instead, we live with the contradiction. We speak through it. We let it leak into the very structure of our prose. For it is in this haunted, hybrid, mimicked language that the postcolonial world finds its voice—not pure, not fluent, but alive.

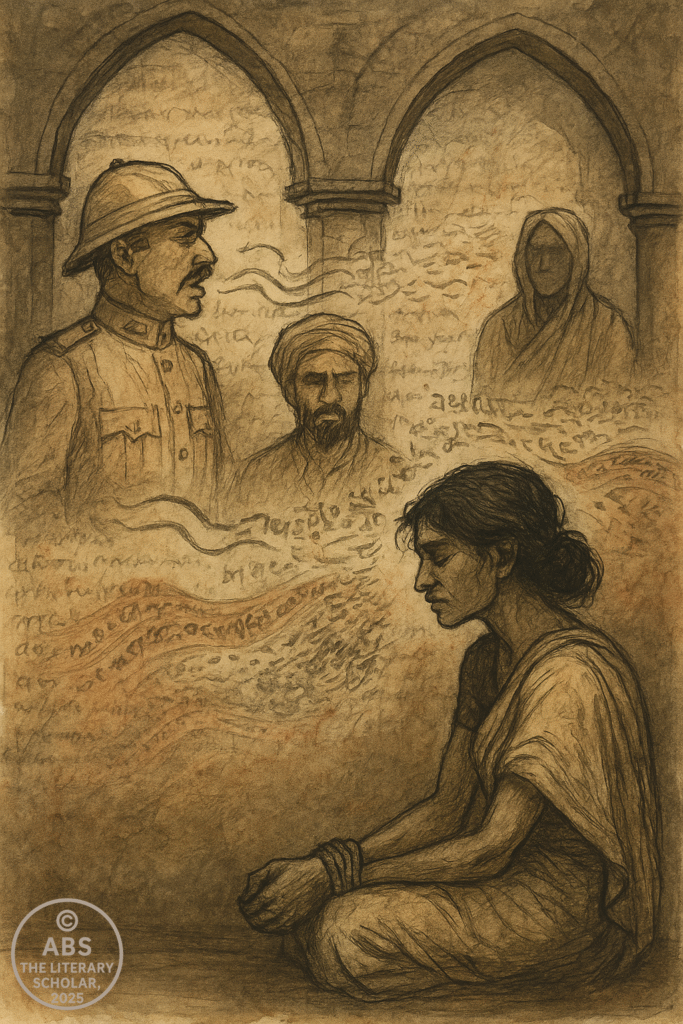

The Silenced Voice: Subalternity and the Question of Speaking

Before literature could be postcolonial, it had to wrestle with silence. Not the poetic silence of suggestion or subtlety, but the deep, systemic muting of entire peoples. In 1988, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak took a scalpel to this silence in her essay Can the Subaltern Speak?, asking what happens when the voice of the oppressed is not just unheard but unhearable—filtered, translated, or overwritten by the very systems that claim to recover it.

To understand subalternity, one must first understand what it is not. It is not merely poverty. It is not merely marginalization. The subaltern, as Spivak draws from the work of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, refers to those whose social position is so radically outside the structures of political and epistemic power that they cannot participate in the production of knowledge about themselves. The subaltern is not simply “spoken for”—they are untranslatable. They are the unheard in a world that only rewards speech in dominant dialects.

In colonial literature, this silence is everywhere. The native is seen, described, imagined—but rarely speaks, and even more rarely in their own terms. When they do speak, it is often through the authorized ventriloquism of anthropologists, administrators, or authors writing in English for Western consumption. The colonized woman, especially, is doubly muted—first as colonized subject, then as female. Spivak’s example of the Hindu practice of sati (widow self-immolation) illustrates this well: both British colonial discourse and Indian nationalist responses spoke over the woman’s act, interpreting it either as barbarism or national sacrifice. Nowhere is her voice present—not in text, not in memory, not in politics.

Spivak’s provocation—“Can the subaltern speak?”—is less a question than an accusation. Even well-meaning efforts to “give voice” to the oppressed often operate on the assumption that the subaltern cannot speak unless translated through Western modes of thought. A translated voice is not a sovereign voice; it is a curated one. And curation, as Spivak suggests, is a kind of re-colonization.

In postcolonial literature, the subaltern is often represented not through direct voice, but through fracture—silences, gaps, ghostly presences that haunt the narrative. Consider Mahasweta Devi’s Draupadi, which Spivak famously translated. The titular character, Dopdi, is an Adivasi woman whose body is subjected to violence by the state. But it is not her violation that shocks; it is her refusal to remain silent afterward. When ordered to clothe herself after a state-sponsored assault, she stands naked and unmoved: “What more can they do?” Her silence is not submission; it is resistance. And in that gesture, the subaltern speaks—but not in the way the oppressor understands.

Postcolonial writers, especially women and indigenous voices, have taken up the challenge Spivak posed—not by answering the question, but by dramatizing its impossibility. The novels of Arundhati Roy, the poetry of Aime Césaire, the short fiction of Bessie Head—all echo with voices breaking through silence, or asking whether silence might itself be a form of speech. These works resist the tidy narrative arc; they embrace rupture and contradiction, offering storytelling as survival, not as spectacle.

In literary theory, Spivak’s work reminds us that critique must be self-critical. One cannot simply include the “other” and feel morally satisfied. Inclusion can be violence if it demands assimilation. The postcolonial critic must ask: Whose knowledge is being cited? Whose experience is being framed? And more importantly, who is still missing from the room?

This is what makes the study of postcolonial subalternity both so important and so ethically precarious. To speak about the subaltern risks reimposing the structures that silenced them in the first place. To remain silent is to risk complicity in their erasure. The task, then, is not to speak for—but to learn to listen, even when what is heard is dissonant, painful, or incomplete.

There is a poetic irony in the fact that literature, which so often prizes voice, is also the site where the voiceless struggle most to be heard. Postcolonial literature does not resolve this contradiction—it foregrounds it. It forces us to confront the limits of representation, the arrogance of analysis, and the uneasy politics of advocacy. It reminds us that reading is not innocent, and that every act of interpretation is also an act of power.

Spivak never really answers her own question. Can the subaltern speak? Perhaps not in the ways we expect. But that does not mean we stop trying to hear. It means we must listen differently—not for eloquence or fluency, but for the ruptures, the silences, the refusals. For what resists translation. For what survives without needing to explain itself.

And in that space—uncertain, uneasy, unfinalized—we begin to understand what postcolonial literature is really asking of us. Not just to read stories from the margins, but to rethink the margins themselves.

Writing Back: Postcolonial Fiction as Counter-Narrative

Achebe, Rushdie, Kincaid—how the novel becomes a site of re-claiming voice

When the British Empire left, it didn’t just leave behind railways, parliaments, and cricket. It left behind a narrative—a story in which it had always been the civilizing hero, and its colonies the grateful, bewildered audience. But postcolonial fiction emerged not to thank the empire for its exit—but to rewrite the very story the empire thought it had finished.

This is what it means to write back. Not politely. Not apologetically. But forcefully, ironically, imaginatively. The phrase “The Empire Writes Back,” first popularized by Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin, captures this reversal with perfect pith. The colonized turn the tools of their colonizers—language, genre, and narrative form—into weapons of critique and liberation. Fiction becomes a form of resistance, a ground on which power can be inverted, questioned, even mocked.

And curiously, the novel—the form most associated with 18th and 19th-century European realism, with Jane Austen’s drawing rooms and Dickens’s moral crusades—becomes the weapon of choice. Postcolonial writers do not abandon the English novel. They possess it, haunt it, and make it speak in new, subversive tongues.

Chinua Achebe: The Parable of Speaking in English

We begin, inevitably, with Chinua Achebe. His Things Fall Apart (1958) is often described as the first great African novel in English, but that title underplays its revolution. What Achebe achieved was a recalibration of narrative perspective itself. He didn’t just write a story about Nigeria—he wrote against the stories that had been written about it.

Achebe once said, “Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” In his hands, the African village becomes a place of complex rituals, tragic heroes, communal tensions—not the mute backdrop of a white man’s journey. The novel follows Okonkwo, a warrior both formidable and flawed, whose downfall is rendered not as primitive collapse, but as cultural interruption—a collision of systems, not a failure of civilization.

And the choice to write in English? It wasn’t capitulation. It was calculation. Achebe deliberately chose “the language of the colonizer” to subvert it from within. He infused English with Igbo proverbs, rhythms, and syntax, turning the colonizer’s tongue into a vessel of native consciousness. This wasn’t mimicry—it was reinscription.

Achebe didn’t just reclaim African identity. He redefined what English literature could be.

Salman Rushdie: Fracturing Form, Fracturing History

If Achebe rewrote the content of empire, Salman Rushdie deconstructed its form. Midnight’s Children (1981) is often read as a postcolonial allegory of India’s birth, but Rushdie himself famously noted that he was less interested in history than in historiography—not what happened, but how it’s remembered, misremembered, and mythologized.

Rushdie’s protagonist, Saleem Sinai, is born at the exact moment of India’s independence. He is not just a character; he is a metaphor wrapped in a man, wrapped in magical realism. He is everywhere and nowhere, hero and unreliable narrator, speaking through a narrative structure that’s chaotic, digressive, and deliberately unstable. Why? Because the postcolonial experience is exactly that—a fragmented inheritance of identities, timelines, languages, and loyalties.

Rushdie’s English is not Achebe’s solemn elegance—it is exuberant, erratic, overloaded. Grammar bends under cultural pressure. The line between realism and fantasy dissolves. It’s a style that doesn’t seek to emulate Western form but explode it from the inside.

Even punctuation becomes political in Rushdie’s hands. The semicolon—the darling of formal logic—is replaced by the dash, the ellipsis, the parenthesis. His prose mimics memory, migration, and mythology. And in doing so, he asserts a radical idea: colonized nations do not have to narrate their pasts in the terms of their colonizers.

Jamaica Kincaid: The Quietest Fury

Postcolonial fiction is not always expansive or surreal. Sometimes it is quiet and razor-sharp. Enter Jamaica Kincaid, the Antiguan-born writer whose prose slices imperial narratives with surgical precision.

In A Small Place (1988), Kincaid turns the travel guide into a political grenade. She addresses the reader directly, often assuming they are a Western tourist basking in Caribbean sun while ignoring the colonial scars beneath the palm trees. “You disembark from your plane. You have finally arrived, and you are a tourist, a North American or European—to be frank, white—and not only that, you have money in your pocket…”

Kincaid’s brilliance lies in her use of the second person—you are not just reading her book, you are implicated in it. Her rage is intimate, lyrical, and precise. There are no grand speeches. There is no magical realism. There is just truth, laid bare.

In Lucy (1990), Kincaid tells the story of a young Caribbean woman working as an au pair in North America. But underneath this seemingly domestic tale lies a deep postcolonial wound—the entanglement of language, desire, labor, and memory. Lucy learns to navigate a world where her body, accent, and past are constantly scrutinized. And yet, in every line, she claims space. The novel is not her escape—it is her assertion.

The Novel as a Site of Resistance

What binds Achebe, Rushdie, and Kincaid is not a shared aesthetic but a shared ethos: the refusal to be narrated by others. Their fiction is not an appeal for empathy. It is a correction of history. A retort. A reclamation.

The novel form, once monopolized by European realism, becomes a place where language is no longer neutral. Where the colonizer’s narrative tools—plot, point of view, diction—are retooled, repurposed, and reloaded. These writers don’t ask to be included in the literary canon. They expand the definition of literature itself.

To write back is to speak where one was silenced. To write back is to point at the empire and say—not “thank you,” but “now listen.”

Unhomed and Exiled: Diaspora, Displacement, and Identity

Rushdie, Naipaul, and others—writing the trauma of belonging nowhere

Some stories begin at home. Others begin where the home ends—when the house is emptied, the suitcase zipped, the language left behind like an old coat that no longer fits. Postcolonial literature has long been preoccupied with displacement, exile, and the elusive idea of home. After all, colonialism didn’t just redraw borders; it fractured identities, scattered communities, and ruptured time. From the forced migrations of indentured laborers to the voluntary dislocations of modern diaspora, writers have wrestled with what it means to belong, to speak, and to write from a place that is neither here nor there.

Postcolonialism in literature is not simply a study of what happened after colonial rule; it is a meditation on where “home” went—and whether it can be retrieved, or must be reinvented. Writers like Salman Rushdie, V.S. Naipaul, Zadie Smith, Jhumpa Lahiri, and many others have charted the emotional, cultural, and psychological cartographies of those who live in-between nations, languages, and selves. The term diaspora itself has evolved from describing physical dispersal to encompassing the internal disorientation of identity in motion.

Rushdie famously wrote, “Our identity is at once plural and partial.” In Imaginary Homelands, he describes the diasporic writer as one who views the original home through the lens of distance—fragmented, idealized, and reconstructed through memory rather than presence. For Rushdie, writing becomes the act of reassembling a shattered mirror. Each shard contains a partial reflection of the past, distorted yet precious. His novel Midnight’s Children not only narrates the story of India’s partition but encodes the very idea of dislocation into its narrative form—broken chronology, unreliable memory, hybrid language.

V.S. Naipaul, on the other hand, often appears less enchanted by the idea of return. His works like A House for Mr Biswas or The Enigma of Arrival convey a deeper malaise—a sense that exile is not merely a condition but an inheritance. Naipaul’s protagonists are rarely comfortable in their skins. They dwell in the shadow of colonial disruption, feeling intellectually tethered to Britain but emotionally estranged from both their origins and their destinations. If Rushdie’s tone is exuberant and polyphonic, Naipaul’s is restrained, melancholic, sometimes bitter. Yet both converge on a similar truth: that home is no longer a place, but a question.

The term unhomed, made prominent by Homi Bhabha, adds a sharper edge to this discussion. An unhomed individual doesn’t just lack a house or country; they no longer feel at home in their own skin. Cultural displacement seeps into identity itself. The colonized subject, taught to admire the colonizer’s language, culture, and values, begins to view their own background as inferior or alien. In this sense, diaspora is not only a scattering of bodies, but a dislocation of the self.

Postcolonial texts often embody this fragmentation in their very style. Language becomes a battlefield—a site where the tension between assimilation and resistance plays out. Writers mix tongues, destabilize grammar, and play with idiom to reflect their hybrid selves. In Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, Jamaican patois, Bangladeshi proverbs, and British slang collide in hilarious and poignant ways. In Lahiri’s The Namesake, Gogol Ganguli’s Bengali name becomes a metaphor for his fractured identity in America.

Displacement also warps the passage of time. The diasporic subject exists in multiple temporal zones—haunted by ancestral history, shaped by the trauma of migration, yet pushed into a present that demands new performances of self. In Season of Migration to the North, Tayeb Salih masterfully reverses the colonial journey, sending a Sudanese man to England only to return with psychological scars and unsettling questions. The novel deconstructs the myth of “civilizing missions” by revealing the emotional cost of cultural transplant.

Memory, then, becomes not just a theme but a method. Postcolonial authors often construct narrative through memory’s logic—non-linear, erratic, tender, and untrustworthy. These stories are seldom told in straight lines. Instead, they echo with absences, interruptions, and the yearning for a center that has long dissolved. Displacement is rarely heroic. It is not the picturesque loneliness of a poet on a hilltop—it is the mundane ache of watching one’s mother tongue die on a child’s tongue.

The sense of exile can be political, too. Think of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who abandoned English entirely in favor of writing in Gikuyu. His linguistic defiance was not merely aesthetic but ideological—a demand to reclaim the tools of meaning-making from imperial hands. He once wrote that language is both a means of communication and a carrier of culture. For many postcolonial authors, then, to write in English is to speak in the colonizer’s voice—but to subvert it from within.

There’s a strange duality in diaspora: it isolates and connects. It produces nostalgia and reinvention. It shatters and spawns hybridity. The exiled writer becomes a translator—not just between languages but between histories, geographies, and epistemologies. They carry homes within them like old, battered suitcases—outdated, yet too precious to discard.

The question of identity in postcolonial diaspora is not answered with certainty but negotiated in layers. Am I this name or that one? This accent or that one? This memory or the one I’ve been told to forget? The works of Mohsin Hamid (Exit West), Michael Ondaatje (Running in the Family), and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Americanah) all tackle these shifting answers. The diasporic self is fluid, resisting closure. It is the child of rupture, raised on fragments, and fluent in contradictions.

In postcolonialism in literature, exile becomes more than a setting—it becomes the condition of being. Whether through forced migration, colonial trauma, or generational inheritance, the writers of diaspora turn the wound of dislocation into a literary art form. They give us characters who speak multiple tongues, belong to multiple worlds, and yet, fully to none. And in doing so, they write a literature not of rootedness, but of motion.

This is not a literature of loss alone. It is also a literature of imaginative reconstruction. A literature that builds bridges from the debris of empire, one sentence at a time.

The Politics of Representation: Orientalism Revisited

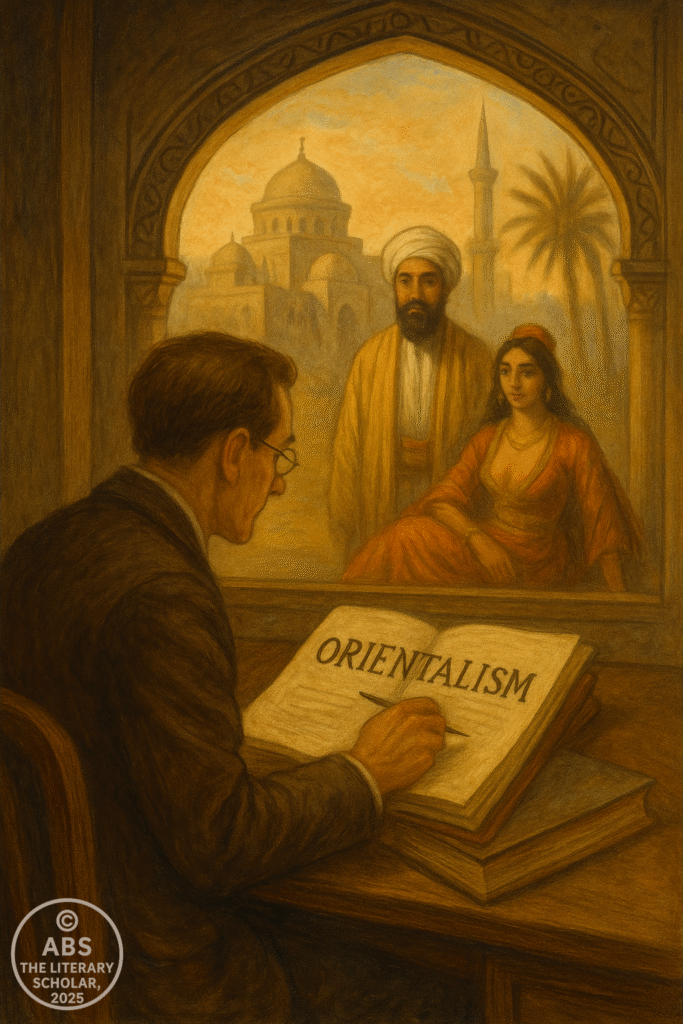

Before postcolonialism in literature began raising its banner of resistance, something far subtler had been happening across centuries of ink and empire. The West was writing the East—but not as chroniclers, as cartographers of culture, as noble anthropologists. No. It was writing the East into existence through fiction, travelogue, and scholarly disguise, wrapping entire civilizations in adjectives, gazes, and fantasies. And it took Edward Said, in 1978, to stop the masquerade. With his landmark work Orientalism, Said exposed what many suspected and few dared to articulate: that representation is not neutral. It is political, deliberate, and, at times, devastatingly efficient.

Said’s Orientalism, now a cornerstone of postcolonial theory, revealed that the West didn’t merely study the East—it invented it. Not the real East, of course, but a constructed, simplified, romanticized other, shaped to reinforce European superiority and colonial authority. The Orient, as it appeared in Western texts, was sensual, irrational, mysterious, and childlike—a seductive landscape of silks, scimitars, harems, and holy men, served up as a contrast to the industrious, rational, modern West. The East became the West’s fantasy playground, a screen onto which Europe could project all its fears and fascinations while reinforcing its sense of cultural dominance.

The Western canon—often held up as a temple of aesthetic achievement—was complicit in this narrative. From Flaubert’s Egyptian courtesans to Kipling’s India, from Shakespeare’s Othello to Byron’s exotic orientalist poetry, literature shaped the Eastern subject as exotic spectacle or noble savage. These weren’t merely imaginative settings; they were frameworks that justified control. Fiction, Said argued, was not innocent. It was ideology wearing robes of storytelling.

And perhaps the most dangerous part of Orientalism was not its overt caricatures, but its assumed neutrality. Western scholars, poets, and travelers would cloak their perspectives in the illusion of objectivity. They would write about the East as though it couldn’t write back—as if it didn’t even speak. And thus, the colonial library grew: rows upon rows of books authored by those with power, describing those without it.

This is precisely where postcolonialism in literature steps in—not just to critique those portrayals but to flip the script. Said opened the door for generations of writers and scholars to re-read and re-write, to question whose story was being told and who was excluded from the narrative machinery. What appears as “Eastern mysticism” or “despotic cultures” in canonical literature becomes a lens into Western insecurity, a need to contrast itself against something inferior. It is not just a matter of misrepresentation; it’s a deliberate construction of knowledge systems that sustain hierarchy.

The postcolonial challenge, then, is not simply to attack Western literature. It is to deconstruct its gaze, interrogate its assumptions, and reimagine the world from outside its empire-shaped optics. This involves rereading texts that seem familiar through unfamiliar eyes. It means asking what lies behind the British gentleman’s sense of order, or what India signifies in A Passage to India beyond the colonial chessboard. It’s about uncovering the silences, the background characters, the misrepresented cultures—and asking why they were made background to begin with.

Said’s influence extends far beyond the page. His insights into cultural imperialism have rippled across fields from media studies to anthropology to politics. But it is in postcolonialism in literature that his vision finds its sharpest resonance—because it is here that representation becomes both weapon and remedy. Literature, after all, helped shape the imperial worldview. Now, literature must also dismantle it.

In revisiting Orientalism today, we also confront our own inherited frameworks. How do we read a Rudyard Kipling or a Joseph Conrad now, knowing what we know? Do we reject them wholesale, or do we mine them for the embedded anxieties of the colonizer? Do we teach these texts alongside voices they tried to erase—those of Tagore, Mahfouz, and Tayeb Salih? Can we tell stories that do not serve empire, or at least see through the ones that did?

Representation is not merely about inclusion. It’s about perspective, agency, and framing. And as Edward Said taught the world to see, the moment we begin to question who is representing whom, and why, we are already practicing postcolonialism in literature. We are reclaiming the gaze.

Nation, Narration, and Fragmented Histories

Nations, said Benedict Anderson, are “imagined communities.” They do not exist as concrete, singular, tangible entities but as vast symbolic constructs formed through shared stories, cultural myths, and the selective memory of history. And in postcolonialism in literature, this idea becomes both weapon and wound. If colonial powers carved empires through maps and armies, then postcolonial writers stitched torn nations back together through narrative—with uneven thread and conflicting memory.

The trauma of colonization wasn’t only about borders being drawn; it was about histories being erased, renamed, and rewritten. Literature, once employed by empires to glorify conquest, has become the very field where empires are dismantled, critiqued, and re-narrated from the underside.

“A Country Called a Text”

Post-independence nations, especially those in Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean, found themselves in the peculiar position of narrating nations that had never fully existed in unified form before colonization. The “India” the British ruled was never a single political entity before the Raj. The “Nigeria” left behind by colonial departure was a hot-wired concoction of over 250 ethnic groups. In this fractured inheritance, postcolonialism in literature became a form of narrative healing—or at the very least, narrative defiance.

Writers like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Chinua Achebe, Arundhati Roy, and Tsitsi Dangarembga explored these imagined fractures not just as historical critique but as artistic opportunity. They didn’t simply write about the nation; they questioned how the nation had come to be written in the first place.

Consider Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children—a magical-realist chronicle where Saleem Sinai is born at the moment of India’s independence, his body and memory becoming absurd metaphors for the fractured national self. “To understand just one life, you have to swallow the world,” writes Rushdie. Postcolonial literature attempts exactly that—and finds the taste bitter, sweet, and confusing all at once.

The Nation as a Story We Argue Over

What’s powerful about postcolonialism in literature is how it exposes that no history is neutral. Narratives of independence, glory, and nationalism often omit the stories of those who remained colonized even after the colonizers left: the indigenous, the lower castes, the women, the queer, the displaced.

Postcolonial novels and poems don’t just add new stories—they challenge the assumption that there ever was one story to begin with. Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (a response to Jane Eyre) gives voice to Bertha Mason, the madwoman in the attic, reimagining her not as madness personified but as a Creole woman destroyed by colonial displacement and patriarchal silencing. This is the project of postcolonial writing: to reclaim, to complicate, and to write against the archival grain.

When the Nation Doesn’t Fit Everyone

The idea of the “nation” in many postcolonial texts is never comfortable. It’s too stitched-together, too shaky, too bound by ethnic, linguistic, or religious fault lines. In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, the Biafran War becomes the site where nationhood shatters into civil strife, and literature becomes the only space where multiple sides can be heard—however uneasily.

Benedict Anderson’s model of nation-as-imagined-community becomes, in postcolonial hands, something more unsettled: a community imagined by whom? For whom? And who gets left out of the imagining?

In postcolonialism in literature, the concept of national identity is frequently deconstructed through the eyes of those who remain “internal outsiders”—those whose ethnicity, caste, gender, or political dissent leaves them stranded in their own countries. The literature doesn’t seek to offer a single truth about the nation, but to expose the truths that have been inconveniently buried.

Gender and Postcolonialism: Double Marginalization

(Feminist Postcolonial Critics—Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Tsitsi Dangarembga)

To be colonized was to be silenced.

To be a woman in a colonized world was to be doubly erased.

The intersection of gender and postcolonialism reveals a stark truth: the history of empire is also a history of how women were written out. As if the trauma of colonial rule were not brutal enough, women endured a layered violence—colonial and patriarchal, public and domestic, political and personal. It’s here that feminist postcolonialism enters: to drag into visibility what had been invisibilized, and to give voice not only to the colonized but to those within them whose voices were stolen twice over.

Feminism Meets the Empire

In her famous essay “Under Western Eyes”, Chandra Talpade Mohanty critiques Western feminism’s tendency to treat “Third World women” as a single oppressed category—powerless, voiceless, and waiting to be saved. But Mohanty flips this gaze. She shows how Western academic discourse often becomes another colonizing force, flattening differences and speaking for women in cultures it barely understands.

According to Mohanty, this universalizing feminist lens reduces diverse women—Indian domestic workers, African farmers, Muslim activists, Caribbean intellectuals—to a monolith. This, she warns, is a new form of intellectual imperialism, where white saviorhood hides behind academic theory.

What Mohanty calls for instead is feminist solidarity across difference—a practice rooted in mutual respect, historical specificity, and the refusal to simplify.

“The relationship between ‘woman’ and ‘colonization’ is not a singular one; it is always mediated by culture, class, race, and historical moment.”

— Chandra Talpade Mohanty

Nervous Conditions and Feminist Rage

If Mohanty theorized the problem, Tsitsi Dangarembga embodied it in fiction. Her searing novel Nervous Conditions (1988) begins with a now-iconic line:

“I was not sorry when my brother died.”

No polite mourning. No sisterly regret. Just raw, unfiltered honesty. Dangarembga’s protagonist, Tambu, is a Zimbabwean girl who dares to want more—education, autonomy, identity. But this ambition makes her a stranger to both her culture and the colonial systems offering her those very opportunities. Her education becomes a double-edged sword: a tool of liberation and an agent of alienation.

The novel brilliantly captures the internal war of postcolonial womanhood: between tradition and modernity, obedience and selfhood, family duty and personal desire. Tambu doesn’t just rebel against colonial rule—she wrestles with her mother’s silence, her aunt’s bitterness, her cousin’s mental breakdown. Dangarembga forces us to ask: when a woman starts to speak, can anyone bear to listen?

The Myth of the Passive Woman

Both Mohanty and Dangarembga explode the myth of the passive Third World woman. They show that women were always resisting—through language, ritual, storytelling, and survival. Their resistance may not always look like protests and slogans; sometimes, it’s the refusal to marry. Sometimes, it’s the act of writing a diary. Sometimes, it’s just staying alive.

This reimagining of agency is crucial. Where colonial narratives portrayed colonized women as either exotic temptresses or helpless victims, feminist postcolonialism reclaims them as complex actors in their own right—women who resist not just empire, but the fathers and husbands who internalized its logic.

The Politics of the Body

The female body—sexualized, scrutinized, disciplined—has always been a site of power struggle in colonial discourse. Empire controlled women’s mobility, dress, sexuality, and labor. Postcolonial feminist literature reclaims the body as both archive and battlefield. In novels like So Long a Letter by Mariama Bâ and Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi, the female body narrates pain that cannot be theorized—only lived.

In such texts, the postcolonial woman’s identity is carved on her skin—through child marriage, widowhood, veiling, sterilization. Yet these bodies also become symbols of rebellion, refusing shame, demanding justice.

Intersectionality Before It Was Named

Postcolonial feminism was doing intersectional analysis long before the term became academic currency. The lives of colonized women are not single-issue campaigns—they are crisscrossed by religion, class, caste, race, and geography. Feminist writers from Africa, South Asia, and the Caribbean insist that liberation must account for context, not just slogans.

For example, Indian Dalit feminist voices challenge both Brahminical patriarchy and upper-caste savior feminism. Afro-Caribbean poets like Grace Nichols write about hair and kitchen smoke with the same political urgency as about revolution and exile. These women aren’t just reacting to empire—they are rewriting the terms of engagement.

Double Marginalization, Endless Strength

To speak of postcolonial women is to speak of survival in stereo—a harmony composed of suffering and defiance. Their lives, too often undocumented in archives, are kept alive in memory, in fiction, in whispered stories passed through generations.

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

— Audre Lorde (often invoked in postcolonial feminist circles)

Postcolonialism, when seen through the lens of gender, reveals how the empire didn’t just conquer lands—it colonized wombs, kitchens, tongues. And feminist thinkers and writers across the globe are still deconstructing that conquest, piece by piece, word by word.

Postcolonialism in Literature Today: Global Capital and Cultural Recolonization

Once the empires crumbled, their flags lowered, and colonies declared independence, one might have assumed the postcolonial narrative to be nearing its final chapter. But as many thinkers, writers, and critics have repeatedly pointed out, the end of political colonization did not signal the end of imperialism—it simply shapeshifted. Today’s postcolonial literature does not only look back in mourning or defiance; it looks around, takes stock, and interrogates the sly new structures of control: global capitalism, media homogenization, linguistic domination, and the stealthy creep of cultural recolonization. In many ways, the empire never really packed up—it just got better at disguising itself behind hashtags, brands, and curriculum vitae.

Where Edward Said once wrote about Orientalism as a West that imagined the East into submission, today’s literary voices are dealing with something far more nebulous. What do you do when the power structure doesn’t wear a crown but a logo? When it doesn’t wave a flag but launches an app? This is the slippery terrain of postcolonialism in literature today—a domain where history, economics, and identity politics entangle in increasingly complex narratives.

Neocolonialism and the Return of the Master’s Tools

Kwame Nkrumah coined the term “neocolonialism” to describe the continuing control of former colonies through economic and cultural means rather than direct rule. Literature, ever the canary in the coal mine, caught this tune early. Writers from the Global South have consistently voiced how financial institutions, development agencies, and international trade bodies have replaced the East India Companies of yore.

Contemporary novels now feature IMF-backed reforms instead of red-coated soldiers, multinational corporations instead of colonial governors, and language policies that determine employment and education rather than passports. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s earlier warning that “economic control follows cultural control” seems painfully prophetic. In texts from Africa, South Asia, and the Caribbean, we see the local entrepreneur crushed under the weight of global franchising, traditional culture squeezed out by urban alienation, and the mother tongue silenced under the thunder of global English.

The empire, it seems, no longer writes back. It writes Excel sheets.

Global English and the New Canon

It is no longer enough to speak English. Now one must speak the right kind of English: grammatically flawless, globally palatable, stripped of local idioms unless they come with a glossary or the stamp of “ethnic flavor.” Many postcolonial writers today walk this tightrope—writing in English, for a global audience, about local themes. But who defines “global”? Whose gaze are they writing for? And what happens to the stories that are too “provincial” or too “political” for mainstream publishing?

This tension is vividly dramatized in the works of writers like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Mohsin Hamid, and Arundhati Roy, whose global readership both empowers and complicates their work. Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness refuses neat categories and accessible Anglophone packaging. It sprawls across identities, languages, and cities, daring readers to catch up or get lost. Hamid’s Exit West threads magical realism into a hyperreal world of refugees and checkpoints, global media and gated borders.

These works remind us that language remains a battlefield, a site where visibility, authenticity, and marketability are constantly negotiated. The colonial legacy of English still lingers—not just in what we write but in what gets published, reviewed, translated, and taught.

Cultural Recolonization and Soft Power

Culture, once the target of missionary zeal, is now the field of corporate diplomacy. Where missionaries once taught hymns, today influencers teach branding. Where colonial education once privileged Shakespeare, today streaming platforms flood screens with globally dominant tropes—from hyper-Americanized romance to sanitised representations of “ethnic authenticity” that pass the global litmus test.

Postcolonial literature, in response, has started to interrogate not only who owns culture but also who monetizes it. Writers like Zadie Smith and Teju Cole explore how metropolitan life and transnational identity both empower and dislocate, how global citizens are often left culturally stateless, and how soft power—through food, fashion, or film—can overwrite local textures with curated cosmopolitanism.

In Amitav Ghosh’s writings, especially The Shadow Lines and The Glass Palace, the reader encounters characters who are fluent in multiple geographies but rootless in all of them. Their speech, clothing, aspirations, and even traumas are global—but never quite grounded. This “floating identity” is the modern equivalent of the colonial subject—always between homes, between tongues, between histories.

Identity Politics, Intersectionality, and Literary Resistance

Modern postcolonial literature doesn’t merely resist colonization; it resists essentialism. Writers no longer wish to be reduced to “spokespersons of their culture” or “native informants.” Many literary voices today engage in intersectional postcolonialism, acknowledging that race, class, gender, sexuality, and nationality do not operate in isolation.

The rise of queer postcolonial literature, Dalit narratives, and indigenous literature has broadened the horizon. They do not merely write back—they write across divides, forcing both global publishers and local gatekeepers to reckon with their biases.

In Jeanine Cummins’ controversial American Dirt, the backlash wasn’t merely about misrepresentation. It was about the commodification of suffering, about who gets to tell which stories and why some stories are still filtered through the gaze of the West. Postcolonial resistance today is not only political—it is editorial.

The Evolving Role of Postcolonial Literature

So what is postcolonialism in literature today? It is no longer just about independence—it is about interdependence. It is not only about reclaiming land—it is about reclaiming narrative sovereignty. It is not just the chronicle of what happened—it is the blueprint of what could still happen if the circuits of power remain unchecked.

From graphic novels to performance poetry, from Afrofuturism to diasporic cookbooks, postcolonial literature now wears many hats and speaks many dialects. Its task has shifted from merely opposing colonial structures to disentangling the deeper roots of cultural domination—especially when those roots are camouflaged as opportunity, globalization, or free markets.

And if colonization was once about silencing, then modern postcolonialism is about polyphony—a chorus of voices, accents, truths, and styles refusing to be flattened.

The Decolonial Future: Literature, Theory, and the Unfinished Struggle

In a world where empires no longer fly flags but still dictate flights, where borders dissolve but inequalities persist, the question arises: is postcolonialism truly post anything? Or is it the academic name for a struggle that, while renamed, remains unfinished?

Postcolonial thought has never been static—it is restless, revisionary, and self-questioning. Born in the furnace of resistance, it once stood defiantly against imperial narratives that sought to flatten worlds, erase cultures, and discipline difference. But as we move deeper into the 21st century, it becomes clear that the task of decolonizing literature is not an act of finality. It is an act of continuation. The colonial wound is not merely a chapter in a book of past trauma; it pulses beneath the modern skin of geopolitics, economics, and identity.

Writers like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o have called for the decolonization of the mind—a rejection of epistemologies imported through conquest. Ngũgĩ’s Decolonising the Mind was not just a literary manifesto but a philosophical declaration: that language is not neutral, that it carries with it the authority of the speaker’s worldview. Thus, to write in English, French, or Portuguese is never a simple matter. It is to traffic in the tongues of historical power. And yet, ironically, these same languages are now being turned against their imperial origins—remixed, hybridized, politicized by writers from the very worlds they once sought to control.

Contemporary literature is rife with this kind of resistance. In NoViolet Bulawayo, Arundhati Roy, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Mohsin Hamid, and Ocean Vuong, we find the fierce persistence of the postcolonial voice—no longer content to respond but to reshape. Their narratives expose the hypocrisies of liberal democracies, the violence of capitalist globalization, and the weaponization of migration, race, and gender.

But the theoretical battlefield has also shifted. Decolonial theory, as distinguished from postcolonialism, has emerged not merely from former colonies but from the Global South—from Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa. Thinkers like Walter Mignolo, Aníbal Quijano, and Boaventura de Sousa Santos have taken aim at what they call “epistemic colonialism”: the erasure of non-European ways of knowing. Their critique is sharper: colonialism, they argue, is not an event but a structure, and modernity itself is inseparable from colonization. To decolonize, then, is to refuse the cognitive empire of “universal knowledge.”

In literary studies, this decolonial urgency manifests as a call to revise the canon, to decenter Shakespeare and Shelley—not to erase them, but to read them alongside and against the voices they once obscured. This is not reverse exclusion. It is literary justice.

And still, the classroom remains contested ground. In the university, decolonization is often reduced to the symbolic—renaming buildings, adding elective courses, hosting panels. But decolonization is not decoration. It demands discomfort. It questions why entire syllabi still orbit around European texts, why indigenous literatures are quarantined as “alternative,” and why global English is treated as literary neutral when it is historically weaponized.

Decolonizing literature, then, means more than inclusion. It means interrogating form, authorship, genre, and even reading practices. It asks whether the novel itself—an Enlightenment form—is adequate to express the nonlinear temporality of oral traditions, the silence of erased histories, or the cyclical grief of exile. Can the postcolonial imagination dwell within inherited Western forms, or must it invent its own?

One sees this experimentation vividly in writers like Marlon James, whose A Brief History of Seven Killings explodes linearity and genre, or in Claudia Rankine, whose hybrid texts confront racial trauma through poetic fragmentation. The forms of literature are shifting—not just because they can, but because they must.

And what of the readers?

If decolonial writing asks for rupture, then it also demands a different kind of reading—one that does not exoticize, does not translate otherness into palatable difference, and does not seek tidy resolution. The decolonial future requires readers who can sit with discomfort, who can read what is not said, and who understand that silence in a postcolonial text may be louder than the most eloquent speech.

We must also recognize that the digital era, far from liberating voices, has introduced new empires—of platform, of algorithm, of surveillance. Social media, while democratizing storytelling, also flattens nuance. Literary culture is increasingly market-driven. Books are reviewed before they are read. Stories from the margins are praised for being “urgent” and “raw,” but are consumed as cultural commodities. Thus, the old dynamic returns: the West reading the Rest—now in Kindle format.

And yet, there is hope.

The very fact that postcolonial literature has had to redefine itself in each generation is proof that it is alive. Theorists now speak of pluriversality—a world where many worlds fit. Writers refuse to be pinned to hyphenated identities. Texts cross genre and geography. What was once “writing back” is now just writing—unapologetic, complex, multilingual, and free.

So no, postcolonialism is not over.

It has merely lost its need to explain itself.

The professor sets down the pen, but not the question.

For the decolonial future is not written in stone—it is still being read, revised, and rewritten.

Line by line, voice by voice.

Signed:

ABS, The Literary Professor

At The Professor’s Desk, www.theliteraryscholar.com

Scroll Index: Explore Literary Theory Explained

(Click any to begin)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance