Who wrote, who won, who refused — and why the biggest literary award is also the most controversial applause in silence.

Once upon a ticking time bomb, there lived a man named Alfred Nobel — a chemist, engineer, weapons manufacturer, and accidental godfather of literary prestige. He invented dynamite, made millions off explosives, and then — as poetic guilt would have it — used that fortune to honour those who tried to repair the damage words like his had done.

Yes, the Nobel Prize is that peculiar contradiction where gunpowder funded poetry, and a deathbed will tried to outwrite a legacy of destruction.

Since 1901, this annual ritual of handing out gold medals and grave citations has made writers go from obscure to immortal — or, depending on who you ask, from literary rebels to Stockholm-approved saints. Some winners have written epics. Some have written lyrics. Some have written barely anything at all. And some have written rejection letters back to the Swedish Academy — now that’s true literary style.

In this scroll, we walk through the scented and scorched pages of Nobel Prize history —

who were crowned with glory,

who refused to wear the crown,

who were forgotten like they never picked up a pen,

and what it really means to be the world’s most applauded writer… in silence.

Because sometimes, the biggest bang in literature doesn’t come from a book.

It comes from a will.

Signed with ink.

And guilt.

And 31 million Swedish kronor.

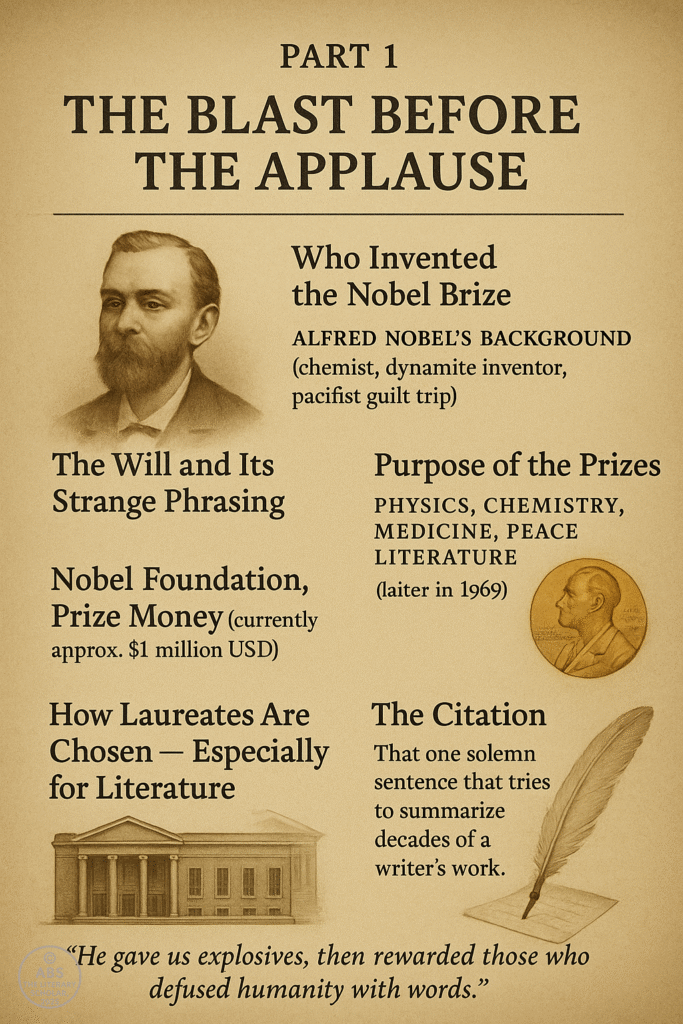

PART 1: The Blast Before the Applause

“He gave us explosives, then rewarded those who defused humanity with words.”

Every grand tradition starts with a paradox. And few are as poetic — or as volatile — as the Nobel Prize.

Let’s begin with the man behind it.

🧪 Who Invented the Nobel Prize?

The Nobel Prize was not invented in a lab.

It was invented in regret.

Alfred Nobel, born in 1833 in Stockholm, was a brilliant inventor, a hopeless romantic, and — inconveniently — a manufacturer of death. A chemist by training and an industrialist by inheritance, Nobel held over 350 patents, but none made as much noise (literally and morally) as dynamite.

His invention revolutionized mining, construction, and unfortunately, warfare. While others celebrated the bang, Nobel heard the echo of future bloodshed.

And then came the twist of fate that gave literature its most awkward benefactor.

One morning in 1888, a French newspaper mistakenly published his obituary — confusing him with his deceased brother. The headline read:

“The merchant of death is dead.”

That single line reportedly shattered Nobel more than all his explosives combined.

Realizing that history might remember him not as a visionary but as a villain, he set out to rewrite his legacy. Not with another invention — but with a will.

And what a will it was.

📜 The Will: Strange Words, Immortal Intentions

In 1895, a year before his death, Alfred Nobel penned a will so dramatic, the Swedish courts spent years debating whether it was even valid. In one baffling, brilliant paragraph, he directed that his vast fortune — 94% of his estate — be used to create annual prizes for those who “have conferred the greatest benefit to mankind.”

He named five fields:

Physics

Chemistry

Medicine (or Physiology)

Peace

Literature — because words too can heal, or at least reveal.

Notice anything missing?

His will didn’t mention Sweden. Or a foundation. Or proper implementation guidelines.

But it did insist the Literature Prize be given to “the most outstanding work in an ideal direction.”

What exactly was “ideal”?

No one knew.

And so began more than a century of awkward interpretations, backroom debates, and gloriously eccentric selections.

🏛️ The Nobel Foundation, the Prestige, and the Paycheck

To carry out this chaotic bequest, the Nobel Foundation was established in 1900. It was given the Herculean task of turning one man’s poetic guilt into institutional grandeur. Since 1901, it has handed out annual prizes — with the 1969 addition of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, which purists still grumble about as a gate-crasher.

Today, winners receive:

A gold medal

A diploma (hand-painted and elegantly illegible)

And roughly 11 million Swedish kronor (≈ $1 million USD), give or take currency crises and inflation.

But beyond the money and ceremony, what laureates really receive is immortality. The kind that makes your books stay in print — even the confusing ones.

🤫 How Laureates Are Chosen: Literature’s Most Exclusive Club

While the science prizes are awarded by various academies and institutes, the Nobel Prize in Literature is chosen by one elusive body: the Swedish Academy — a group so secretive, they make the Vatican look like an open mic night.

Each year, a flood of nominations arrive — but only from a select list of individuals and institutions invited to suggest candidates. The shortlist is guarded like a state secret. The deliberations are sealed for 50 years. And yes, writers who don’t write in European languages have historically been lost in translation… or simply lost.

There are no interviews. No acceptances. No press tours.

Just a sudden announcement, a breathless phone call, and your publisher running out of stock in 30 minutes.

🖋️ The Citation: One Sentence to Summarize a Life

If you’ve ever tried summarizing a 400-page novel in a single tweet, welcome to the pain of the Nobel citation.

Each Literature laureate is introduced with a short, solemn sentence that’s meant to explain why they won. Sometimes it’s poetic:

“For her poetic voice, that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.” — 2009, Herta Müller

Sometimes it’s vague:

“For a narrative imagination that with encyclopedic passion represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life.” — 2006, Orhan Pamuk

And sometimes it’s just deeply, delightfully Swedish:

“For creating new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” — 2016, Bob Dylan

(Translation: “We think song lyrics count too. Please don’t @ us.”)

🎇 Legacy with a Bang

The Nobel Prize, especially in Literature, is not just an award.

It’s a statement.

A mirror.

A firestarter.

And sometimes, a politically correct apology for centuries of literary ignorance.

It has launched obscure poets into stardom and sparked more debates than it has silenced. It has been whispered, protested, rejected, and even… forgotten.

But every October, the world still leans in and waits.

For that one name.

That one citation.

That one moment when the writer’s silence is broken by applause.

And all because one man — who made the world explode — wanted to leave behind a legacy that could make it read.

1901 – Sully Prudhomme (France)

1902 – Theodor Mommsen (Germany)

1903 – Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (Norway)

1904 – Frédéric Mistral / José Echegaray (France / Spain)

1905 – Henryk Sienkiewicz (Poland)

1906 – Giosuè Carducci (Italy)

1907 – Rudyard Kipling (United Kingdom)

1908 – Rudolf Eucken (Germany)

1909 – Selma Lagerlöf (Sweden) 👩

1910 – Paul Heyse (Germany)

1911 – Maurice Maeterlinck (Belgium)

1912 – Gerhart Hauptmann (Germany)

1913 – Rabindranath Tagore (India) 🌍

1914 – Romain Rolland (France)

1915 – Verner von Heidenstam (Sweden)

1916 – Carl Spitteler (Switzerland)

1917 – Knut Hamsun (Norway)

1918 – Not awarded (WWI)

1919 – Carl Friedrich Georg Spitteler (Switzerland)

1920 – Knut Pedersen Hamsun (Norway)

1921 – Anatole France (France)

1922 – Jacinto Benavente (Spain)

1923 – William Butler Yeats (Ireland)

1924 – Wladyslaw Reymont (Poland)

1925 – George Bernard Shaw (Ireland)

1926 – Grazia Deledda (Italy) 👩

1927 – Henri Bergson (France)

1928 – Sigrid Undset (Norway) 👩

1929 – Thomas Mann (Germany)

1930 – Sinclair Lewis (USA)

1931 – Erik Axel Karlfeldt (Sweden)

1932 – John Galsworthy (United Kingdom)

1933 – Ivan Bunin (Russia)

1934 – Luigi Pirandello (Italy)

1935 – Not awarded

1936 – Eugene O’Neill (USA)

1937 – Roger Martin du Gard (France)

1938 – Pearl S. Buck (USA) 👩

1939 – Frans Eemil Sillanpää (Finland)

1940–1943 – Not awarded (WWII)

1944 – Johannes Vilhelm Jensen (Denmark)

1945 – Gabriela Mistral (Chile) 👩

1946 – Hermann Hesse (Germany/Switzerland)

1947 – André Gide (France)

1948 – T.S. Eliot (United Kingdom/USA)

1949 – William Faulkner (USA)

1950 – Bertrand Russell (United Kingdom)

1951 – Pär Lagerkvist (Sweden)

1952 – François Mauriac (France)

1953 – Winston Churchill (United Kingdom)

1954 – Ernest Hemingway (USA)

1955 – Halldór Laxness (Iceland)

1956 – Juan Ramón Jiménez (Spain)

1957 – Albert Camus (France)

1958 – Boris Pasternak (USSR) ⚠️

1959 – Salvatore Quasimodo (Italy)

1960 – Saint-John Perse (France)

1961 – Ivo Andrić (Yugoslavia)

1962 – John Steinbeck (USA)

1963 – Giorgos Seferis (Greece)

1964 – Jean-Paul Sartre (France) ⚠️

1965 – Mikhail Sholokhov (USSR)

1966 – Shmuel Yosef Agnon / Nelly Sachs (Israel / Germany) 👩

1967 – Miguel Ángel Asturias (Guatemala)

1968 – Yasunari Kawabata (Japan) 🌍

1969 – Samuel Beckett (Ireland)

1970 – Alexandr Solzhenitsyn (USSR)

1971 – Pablo Neruda (Chile)

1972 – Heinrich Böll (Germany)

1973 – Patrick White (Australia)

1974 – Eyvind Johnson / Harry Martinson (Sweden)

1975 – Eugenio Montale (Italy)

1976 – Saul Bellow (USA)

1977 – Vicente Aleixandre (Spain)

1978 – Isaac Bashevis Singer (USA/Poland)

1979 – Odysseas Elytis (Greece)

1980 – Czesław Miłosz (Poland)

1981 – Elias Canetti (United Kingdom / Bulgaria)

1982 – Gabriel García Márquez (Colombia)

1983 – William Golding (United Kingdom)

1984 – Jaroslav Seifert (Czechoslovakia)

1985 – Claude Simon (France)

1986 – Wole Soyinka (Nigeria) 🌍

1987 – Joseph Brodsky (USA / Russia)

1988 – Naguib Mahfouz (Egypt) 🌍

1989 – Camilo José Cela (Spain)

1990 – Octavio Paz (Mexico)

1991 – Nadine Gordimer (South Africa) 👩 🌍

1992 – Derek Walcott (Saint Lucia) 🌍

1993 – Toni Morrison (USA) 👩

1994 – Kenzaburō Ōe (Japan) 🌍

1995 – Seamus Heaney (Ireland)

1996 – Wislawa Szymborska (Poland) 👩

1997 – Dario Fo (Italy)

1998 – José Saramago (Portugal)

1999 – Günter Grass (Germany)

2000 – Gao Xingjian (France / China) 🌍

2001 – V. S. Naipaul (United Kingdom / Trinidad) 🌍

2002 – Imre Kertész (Hungary)

2003 – J. M. Coetzee (South Africa) 🌍

101. 2000 – Gao Xingjian (France / China) 🌍

102. 2001 – V. S. Naipaul (United Kingdom / Trinidad) 🌍

103. 2003 – J. M. Coetzee (South Africa) 🌍

104. 2004 – Elfriede Jelinek (Austria) 👩

105. 2005 – Harold Pinter (United Kingdom)

106. 2006 – Orhan Pamuk (Turkey) 🌍

107. 2007 – Doris Lessing (United Kingdom) 👩

108. 2008 – Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio (France)

109. 2009 – Herta Müller (Germany / Romania) 👩

110. 2010 – Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru) 🌍

111. 2011 – Tomas Tranströmer (Sweden)

112. 2012 – Mo Yan (China) 🌍

113. 2013 – Alice Munro (Canada) 👩

114. 2014 – Patrick Modiano (France)

115. 2015 – Svetlana Alexievich (Belarus) 👩 (non-fiction)

116. 2016 – Bob Dylan (USA) ⚠️ (songs as literature – controversial)

117. 2017 – Kazuo Ishiguro (United Kingdom / Japan) 🌍

118. 2018 – Olga Tokarczuk (Poland) 👩 (awarded in 2019 due to 2018 scandal)

119. 2019 – Peter Handke (Austria) ⚠️ (Bosnian War controversy)

120. 2020 – Louise Glück (USA) 👩 (poetry)

121. 2021 – Abdulrazak Gurnah (Tanzania) 🌍

122. 2022 – Annie Ernaux (France) 👩

123. 2023 – Jon Fosse (Norway)

124. 2024 – Han Kang (South Korea) 👩 🌍

PART 3: The Ones Who Said ‘Thanks, But No Thanks’

You know a prize is powerful when refusing it makes bigger headlines than winning it.

The Nobel Prize in Literature is the literary equivalent of Olympus. You don’t climb it; you’re summoned. But not everyone bows when Stockholm calls.

Welcome to the hall of literary rebels, reluctant laureates, and those who looked at the world’s most prestigious medal and said, “Pass.”

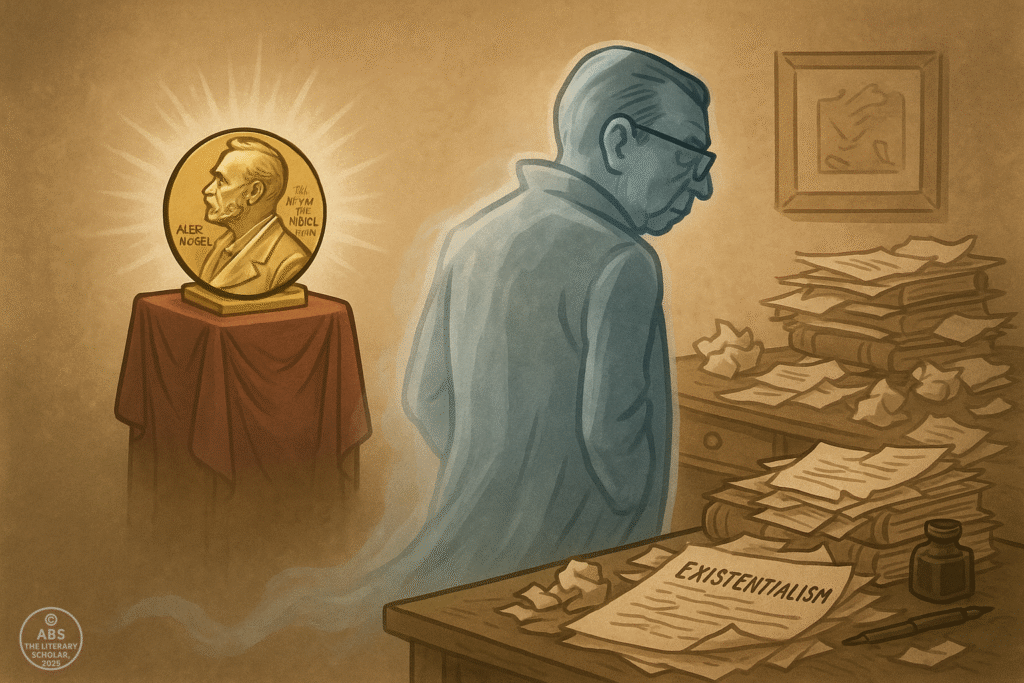

🧼 Jean-Paul Sartre (1964): The Philosopher Who Declined the Gold

“A writer should refuse to allow himself to be transformed into an institution.”

Sartre didn’t just walk the existential talk — he strutted it all the way past the Nobel gates. In 1964, he made headlines by refusing the Nobel Prize for Literature. The Swedish Academy praised his contributions to literature, freedom, and thought.

Sartre said, “Merci, but non.”

His reason? He had consistently refused all official honours — including France’s Legion of Honour. To accept the Nobel would, in his words, be to turn himself into a monument, and monuments, he believed, were just tombstones that stood up straight.

The Nobel Committee was bewildered. France was proud. Sartre remained philosophically aloof, writing on, thinking on — with no medal weighing down his conscience.

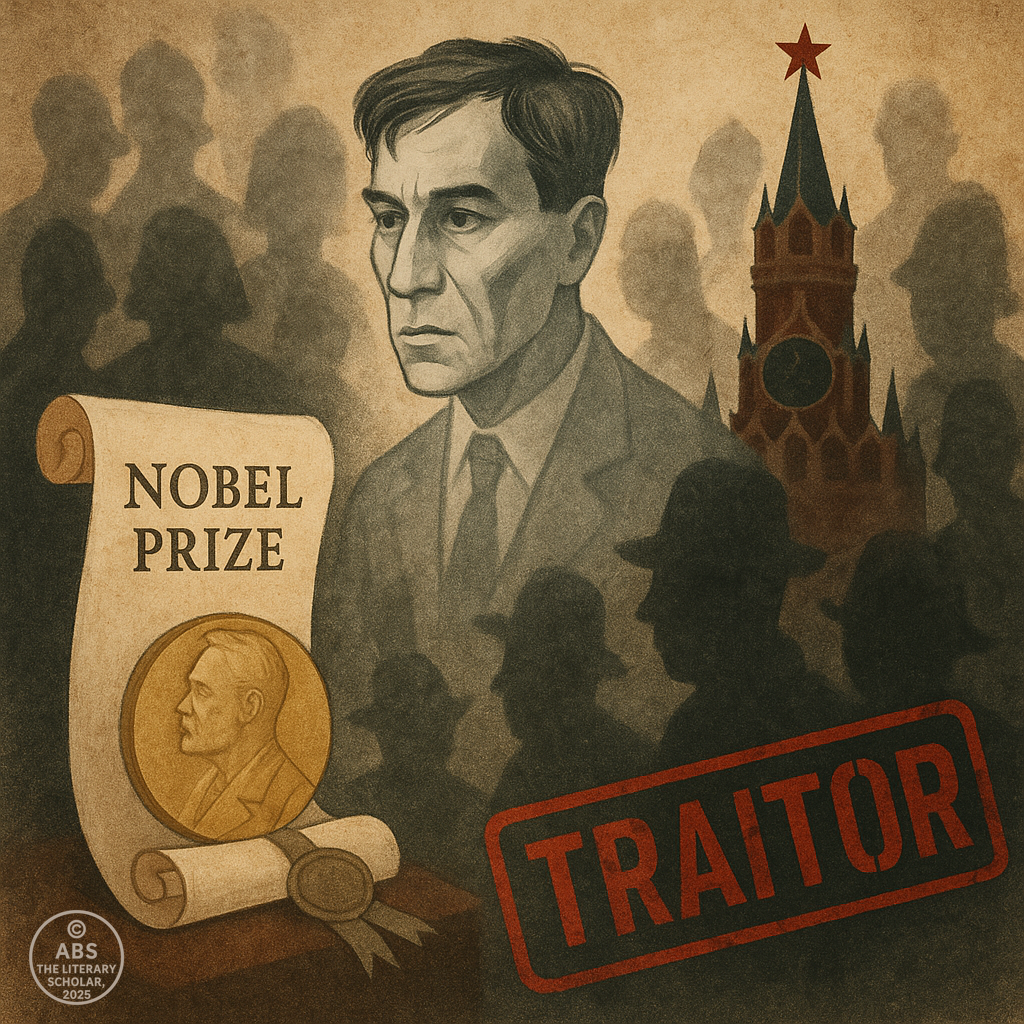

🕊️ Boris Pasternak (1958): The Poet Who Was Silenced

“I am immensely grateful, touched, proud, surprised, overwhelmed.”

– Pasternak’s initial telegram to the Academy.

And then: “I must renounce the prize.”

Pasternak’s Nobel win for Doctor Zhivago was both glorious and dangerous. While the West hailed him as a literary hero, the Soviet Union saw the Nobel as a political ambush. The novel had been banned in the USSR, smuggled out, and published in Italy — a literary act of treason.

After a week of celebration, Pasternak was threatened with exile, public condemnation, and removal from the Soviet Writers’ Union. With a broken heart, he declined the award under pressure.

The Nobel remained on the shelf — untouched — until 1989, when his son finally accepted it on his behalf.

🚫 Le Duc Tho (1973 Peace Prize): Diplomacy Denied

While not a Literature laureate, Le Duc Tho deserves a chapter here.

Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize jointly with Henry Kissinger for the Vietnam War ceasefire, Le Duc Tho declined the prize on the grounds that:

“Peace had not yet been established.”

Translation: “Nice medal, but we’re still bombing each other.”

A rare moment when integrity outweighed ceremony, and the world remembered that a peace prize without peace is just very expensive irony.

💸 When Writers Gave Away the Prize (or the Money)

Not everyone who accepted the prize kept the money or even took it with celebration:

George Bernard Shaw (1925): Famously said,

“I can forgive Nobel for inventing dynamite, but only a fiend in human form could have invented the Nobel Prize.”

He accepted the award, then refused the prize money, suggesting it be used to translate his works into Swedish. Now that’s peak sarcasm.

Albert Schweitzer and Mother Teresa (Peace Prize) gave away their prize money to their causes.

Toni Morrison, Nadine Gordimer, and others have used their Nobel platform to elevate social justice — turning personal prestige into public voice.

❌ The Ones Who Never Got the Call (And Probably Should Have)

The Nobel’s glitter doesn’t always land where it should.

Leo Tolstoy – Never won. Why? Too radical, too spiritual, too uncontrollable.

James Joyce – Never won. Too dense, too controversial, too non-linear for linear minds.

Virginia Woolf – Ignored. Maybe because she was a woman, maybe because she was a modernist, or maybe because the Swedish Academy hadn’t figured out stream of consciousness.

Jorge Luis Borges – Rumoured to be blacklisted due to political sympathies.

Vladimir Nabokov – Nominated several times, never won. Apparently, Lolita wasn’t quite what the Academy meant by “idealistic literature.”

🧭 Eurocentrism, Sexism, and Literary Politics

The Nobel Prize in Literature, for all its grandeur, has often been a mirror of Western literary bias:

Over 70% of laureates have been European.

Only 18 women have won from 1901 to 2024.

Entire continents like Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East remain underrepresented.

Bob Dylan‘s win (2016) caused a literary meltdown. “A songwriter?” purists gasped. “Is Leonard Cohen next?”

And then came the 2018 scandal, when allegations of sexual misconduct and internal corruption shook the Swedish Academy, leading to a postponed prize year. It was the literary equivalent of the Oscars forgetting to nominate a Best Picture.

🖋️ To Win or Not to Win? That Is Not the Question.

The Nobel isn’t just a prize. It’s a narrative.

Some accept it with humility.

Some refuse it with defiance.

Some wait their whole lives — and never get it.

And others, like Tolstoy, simply don’t need it.

Because in the end, the greatest honour a writer can receive is not medal metal, but readers who stay.

PART 4: The Literary Thunderclaps – What Got Them the Prize

“Because sometimes, a single book makes enough noise to wake Sweden.”

The Nobel Prize is not a reward for having published something. It’s a coronation for having shifted literature itself. But what does that look like? What do these laureates actually write that earns them applause dipped in gold and a citation written like a eulogy?

Let’s take a curated stroll through the thunderclaps — the works that echoed all the way to Stockholm.

🌪️ Gabriel García Márquez – One Hundred Years of Solitude (1982)

A family tree, a banana massacre, ghosts, incest, and magical rain — basically, a telenovela written by a prophet.

This Colombian masterpiece made magical realism mainstream. The town of Macondo feels realer than most cities with airports. Márquez didn’t just write a novel — he summoned a mythology. One sentence from this book could replace half the world’s GDP reports in emotional accuracy.

📜 Citation:

“For his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination.”

🪶 Toni Morrison – Beloved (1993)

Slavery, memory, and a ghost that is more real than history’s amnesia.

Morrison took the unspeakable and wrote it down — not for shock, but for reckoning. Beloved is a haunted house novel, yes. But the ghost is America’s conscience, and Morrison makes sure no reader gets to pretend it’s just metaphor.

📜 Citation:

“Who in novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality.”

🕊️ Rabindranath Tagore – Gitanjali (1913)

Spiritual poetry so profound that even God probably paused to listen.

Tagore became the first non-European to win the prize. He wrote poems that felt like sunrises wrapped in silk. And yes, he translated his own Bengali verses into English — and somehow made English sound like it was born in Bengal.

📜 Citation:

“Because of his profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse, by which he has made his poetic thought a part of the literature of the West.”

🫖 Kazuo Ishiguro – The Remains of the Day, Never Let Me Go (2017)

Repressed emotion as an Olympic sport. May cause sudden melancholy over perfectly folded napkins.

Ishiguro writes with a scalpel dipped in sadness. His characters don’t scream — they apologize silently for feeling. Whether it’s a loyal English butler or a clone grappling with identity, his prose proves that understatement can scream louder than trauma.

📜 Citation:

“Who, in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.”

🔥 Pablo Neruda – Canto General, political and love poetry (1971)

He could write a poem about onions and make you cry harder than your ex ever did.

Neruda’s poetry was volcanic — passionate, political, personal. He made love political and politics poetic. From odes to bread to elegies of dictatorships, he proved the pen is mightier — and sometimes sexier — than the sword.

📜 Citation:

“For a poetry that with the action of an elemental force brings alive a continent’s destiny and dreams.”

❄️ Orhan Pamuk – Snow, My Name is Red (2006)

Where East and West fight over identity like divorced parents at a PTA meeting.

Pamuk’s work is a philosophical thriller disguised as literary fiction. He paints Istanbul with narrative calligraphy — elegant, layered, and always haunted by the ghosts of empires, veils, and revolutions.

📜 Citation:

“Who in the quest for the melancholic soul of his native city has discovered new symbols for the clash and interlacing of cultures.”

🧳 Olga Tokarczuk – Flights, The Books of Jacob (2018)

Her novels travel more than most passports do. Luggage not included.

Tokarczuk writes like a time-traveling therapist. Her books dissect identity, migration, myth, and mysticism — but without ever losing narrative elegance. Think Borges on a Eurail pass, with a philosophy degree in one hand and folklore in the other.

📜 Citation:

“For a narrative imagination that with encyclopedic passion represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life.”

⏳ Harold Pinter – Theatre of Menace (2005)

Dialogue so sharp, it bleeds through the silence.

Pinter gave the world the Pinter Pause — the terrifying moment between lines where characters (and audiences) suffocate in meaning. His plays are full of nothingness that says everything. You leave the theatre unsure if you watched a play or stared into a well of human anxiety.

📜 Citation:

“Who in his plays uncovers the precipice under everyday prattle and forces entry into oppression’s closed rooms.”

🎸 Bob Dylan – Song Lyrics as Literature (2016)

The times, they were a-changin’… and so were the Nobel rules.

The decision sparked chaos. Academics clutched their Collected T.S. Eliots while folk singers rejoiced. Dylan didn’t write novels or verse plays — he wrote lyrics. And suddenly, the Nobel said, “That counts too.” Love him or loathe the move, Dylan opened the doors for a broader definition of literary merit.

📜 Citation:

“For having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.”

⚡ The Echo That Earns the Medal

Not all laureates win for one book. Some win for an entire shelf of ideas. But behind every Nobel is a work — or a style — that refused to shut up, sit down, or behave like “ideal literature.”

Sometimes, it was a poem.

Sometimes, a ghost.

Sometimes, a song that refused to be just a song.

But every time, it was a thunderclap.

Loud enough to shake Stockholm.

PART 5: Beyond the Applause – Politics, Protest, and Power

“Sometimes it’s not the silence of literature, but the silence of the committee that is deafening.”

Ah, the Nobel Prize — the gold standard of literary legacy. But dig beneath the glitter, and you’ll find dust — political, cultural, and moral.

This part of the scroll is dedicated not to the words that were spoken, but to the ones that weren’t awarded.

🌍 Missing Continents, Forgotten Voices

The prize claims to celebrate global literature, but one look at the map suggests the globe may still be under construction. Over 70% of literature laureates have hailed from Europe or North America.

Africa? Just four winners in over a century.

South Asia? One (Tagore, 1913), as if the subcontinent never wrote another sentence after that.

The Middle East? Sparse.

Southeast Asia? All but invisible.

Indigenous literature? Still waiting for an invitation.

It’s less “World Literature” and more “Literature of the World We Can Read in Swedish.”

🧨 Peter Handke and the Bosnian War

In 2019, Peter Handke won the prize. A man whose literary achievements were immediately overshadowed by his public support for Slobodan Milošević, the Serbian leader charged with war crimes.

The world recoiled.

Survivors protested.

And the Swedish Academy replied, essentially: “We separate the art from the artist.”

But how do you reward a voice that defended genocide — while claiming to honour the ideal direction of literature?

Sometimes, the Nobel doesn’t misfire. It detonates.

🎸 Bob Dylan’s Delayed Response

In 2016, Bob Dylan won the Literature prize and… said nothing. For weeks.

When the committee finally reached him, it felt less like literary recognition and more like trying to RSVP a ghost.

“If someone had told me I had a chance to win the Nobel, I’d have said I had about the same chance as standing on the moon.”

— Dylan, eventually.

He skipped the ceremony, sent a speech months later, and taught the Nobel something important: not all bards want your applause.

🧂 Gender Disparity and Linguistic Elitism

Of the 121 Nobel Literature laureates so far, only 18 have been women.

That’s less than 15%.

Even tech companies have better gender ratios.

And let’s not forget the linguistic glass ceiling — English, French, German, and Swedish dominate. Good luck getting noticed if your masterpiece is in Wolof, Sinhala, or Quechua.

It’s not just sexism. It’s translationism.

🕳️ The 2018 Scandal: Silence in Stockholm

For the first time since WWII, no Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded in 2018. Why?

A member of the Swedish Academy was accused of sexual assault.

Several others resigned.

The trust was broken.

The Academy, usually cloaked in mystery, became the center of tabloid fever.

The literary world gasped — not just at the crime, but at the collapse of an institution built on silence, integrity, and invisible judgment.

💀 Posthumous Prizes? Not in Literature.

While Nobel prizes have occasionally gone posthumous (if the laureate died between announcement and ceremony), literature does not award the dead.

So if you’re planning to write something that shifts human consciousness — do it quickly. Or hire a ghostwriter before becoming one.

And now… one last scroll before we fold the gold.

PART 6: The Literary Scholar’s Honour List

“If the Nobel had taste, these would be on the shelf.”

– The Literary Scholar, shaking the dust off justice

Some writers never won. Not because they lacked talent — but because the committee lacked imagination.

Here are the ones who should have heard that phone call in October.

✨ Virginia Woolf

“For dismantling the structure of narrative time, slicing open consciousness, and walking us through the haunted halls of the female mind — all before breakfast.”

Her omission is literary blasphemy. She gave us stream of consciousness, psychological depth, gender fluidity, and prose like rain on marble. But maybe she was too modern for Stockholm. Or too female.

📚 James Joyce

“For expanding the boundaries of the novel so far that most readers packed their bags and left halfway through.”

Ulysses redefined fiction. Finnegans Wake nearly undefines it. Joyce wasn’t just a writer — he was a linguistic terrorist. The Nobel didn’t give him the prize. Probably because they couldn’t read the book.

🌍 Chinua Achebe

“For decolonizing the English language one proverb at a time, and reminding the West that the story always depends on who’s holding the drum.”

A Things Fall Apart is one of the most read, taught, and quoted novels globally — and yet Achebe never won. But he made world literature impossible to discuss without Nigeria in the room.

🔮 Jorge Luis Borges

“For seeing time as a hallway, mirrors as destiny, and the universe as a badly shelved library — all in a paragraph.”

The master of the metaphysical short story. He built labyrinths with words, dreamt up infinite libraries, and philosophized like a poet with a monocle. But the prize? Forever just out of reach.

🎭 Anton Chekhov

“For teaching us that life is what happens between one cough and the next, and that tragedy wears slippers.”

No other playwright captured the quiet despair of everyday people like Chekhov. He didn’t win a Nobel — probably because by the time they noticed, he had already coughed himself out of contention.

📖 Margaret Atwood (still possible)

“For constructing speculative worlds so sharp they cut through reality, and for turning dystopia into prophecy decades before anyone called it ‘The Handmaid’s Era.’”

She still has time. But let’s hope the Academy moves faster than Gilead. Because if anyone deserves a golden circle of validation, it’s the woman who warned us — and still has receipts.

ABS folds the scroll, but not the applause.

The Nobel is a seal, not a soul.

It cannot define greatness — only nod at it, sometimes late, sometimes wrong.

Because in the end, it’s not the medal but the words that outlive the noise.

And the best literature has always been a rebellion against who gets to decide what literature is.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance