Nagananda by Harsha Analysis: Summary, Themes & Characters

Introduction to Harsha, the Author of Nagananda

Harsha (also known as Harshavardhana), who ruled North India from 606 to 648 CE, was one of the rare kings in Indian history who combined political authority with literary brilliance. A ruler of the Pushyabhuti dynasty, Harsha inherited a fragmented kingdom but transformed it into a stable and culturally vibrant empire. His reign is often described as the golden age of Northern India, marked by patronage of the arts, religious tolerance, and intellectual flourishing.

As an author, Harsha stands apart because he wrote not merely as a ruler but as a reflective thinker. He composed three Sanskrit plays—Ratnavali, Priyadarsika, and Nagananda—each different in tone and theme. Unlike the romantic elegance of Ratnavali or the courtly charm of Priyadarsika, Nagananda reveals Harsha’s deeper spiritual and philosophical concerns.

Harsha was influenced by Buddhist compassion, Hindu mythology, and classical Sanskrit dramaturgy. This blend allowed him to craft Nagananda, a play centered not on heroic conquest but on moral heroism and self-sacrifice. Through Jimutavahana’s character, Harsha expresses his belief that true kingship and true greatness lie in protecting the weak and uplifting the oppressed.

As both emperor and playwright, Harsha remains a unique figure whose literary works reflect the ethical ideals he sought to uphold as a king.

Harsha’s Three Rupakas: Priyadarshika, Ratnavali, and Nagananda

Emperor Harsha wrote three Sanskrit Rupakas (full-length dramatic compositions). Of these, Priyadarshika and Ratnavali belong to the sub-genre Nāṭikā (a light, romantic drama), while Nagananda is structurally and thematically a full Nāṭaka, a higher, heroic form of drama.

Harsha’s works are not the products of a casual king dabbling in literature. They reflect a ruler who understood court culture, emotional psychology, and the moral demands of power. Each play shows a different facet of his intellectual personality.

1. Priyadarshika — The Graceful Romance

Genre: Nāṭikā (light drama)

Priyadarshika is a romantic court drama filled with mistaken identities, palace intrigue, and gentle humor. It revolves around the love story of King Dridhavarman and the heroine Priyadarshika, whose union faces obstacles but ultimately succeeds. The play highlights themes of youthful affection, jealousy, friendship, and political complications—wrapped in elegant language and a soft emotional tone.

This work shows Harsha’s comfort with courtly elegance, refined emotion, and social comedy, proving that he could match the sophisticated taste of the elite audiences in his court.

2. Ratnavali — Harsha’s Masterpiece of Courtly Comedy

Genre: Nāṭikā (light romantic comedy)

Ratnavali is Harsha’s most popular play and often ranks among the best examples of Sanskrit dramatic comedy. The plot centers on King Udayana and the heroine Ratnavali, whose love story unfolds through humorous misunderstandings, clever disguises, and playful court dynamics.

This is Harsha at his most polished:

witty dialogue

graceful romantic scenes

intelligent female characters

comic misunderstandings handled with finesse

The play treats love not as tragedy or sacrifice but as refined amusement within a royal setting. Ratnavali established Harsha’s reputation as a skilled writer of sophisticated dramatic entertainment.

3. Nagananda — The Pinnacle of Spiritual Drama

Genre: Nāṭaka (heroic drama)

Nagananda is Harsha’s most ambitious and serious play. It breaks away from romantic themes and focuses on moral heroism, sacrifice, and compassion. The story of Prince Jimutavahana, who offers himself to save the Naga race from daily sacrifice to Garuda, embodies the bodhisattva ideal.

Unlike the light tone of his two Nāṭikās, Nagananda explores:

suffering and empathy

ethical courage

spiritual ideals

the transformation of violence into compassion

The invocation to Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisattva of Mercy, shows strong Buddhist influence. This makes Nagananda a rare example of religious and philosophical theatre in Sanskrit literature.

How Harsha’s Three Works Show His Range

Priyadarshika → Light romance, gentle courtly emotion

Ratnavali → Sophisticated comedy and royal wit

Nagananda → Deep moral drama and spiritual symbolism

Together, they reveal:

his command over multiple dramatic moods

his sensitivity to human emotion

his capacity to shift from entertainment to ethics

his unique blending of Buddhist compassion and Hindu mythology

Harsha’s corpus is essentially a three-sided mirror—reflecting the pleasure of romance, the laughter of comedy, and the gravity of ethical sacrifice.

Nagananda: Introduction

Nagananda (Devanagari: नागानन्द), meaning “Joy of the Serpents,” is one of the most remarkable Sanskrit plays attributed to Emperor Harsha, who ruled from 606 to 648 CE. Harsha was not just a ruler; he was a scholar-king who wrote with a mix of spiritual depth and dramatic instinct. Nagananda stands out because it blends Buddhist compassion, Hindu mythological elements, and classical Sanskrit dramaturgy in a single narrative.

The play centers on Jimutavahana, a prince who willingly sacrifices himself to save the serpent race from the deadly demigod Garuda. It is one of the few Sanskrit plays where self-sacrifice becomes the primary heroic ideal, making the protagonist morally larger than life rather than merely victorious in battle.

Unlike the romantic dramas of Kalidasa or the political plays of Vishakhadatta, Harsha’s Nagananda pushes the boundaries of classical theatre by focusing on spiritual heroism and universal compassion. It has mythology, dharma, moral conflict, and emotional resonance — all in a tight, elegant Sanskrit dramatic structure.

Nagananda, “The Joy of the Serpents,” is one of the most unusual and spiritually charged Sanskrit plays ever composed. Attributed to Emperor Harsha, it blends the elegance of classical dramatic form with Buddhist compassion, Hindu mythology, and a moral universe in which heroism is measured not by conquest but by sacrifice. The play revolves around the noble prince Jimutavahana, whose willingness to give his own life to save a threatened community becomes the heart of Harsha’s dramatic vision.

The play opens with a benediction to Avalokitesvara, the Buddhist bodhisattva of compassion. This itself is extraordinary in Sanskrit drama, which typically begins with invocations to Hindu deities such as Shiva or Vishnu. Harsha’s invocation sets the tone: this is a play where compassion will outweigh power, and self-sacrifice will outweigh royal glory.

We meet Jimutavahana, prince of the Vidyadharas — a celestial race endowed with magical abilities but also bound by dharma. Though a royal heir, Jimutavahana has renounced worldly ambition, choosing instead a life devoted to service, gentleness, and moral duty. His character embodies a blend of princely dignity and saint-like compassion, signaling that he will not behave like the typical dramatic hero driven by romance or battlefield valor.

Jimutavahana arrives with his father on the Malaya mountain, a serene and spiritually charged setting where hermitages and ascetics live in quiet harmony. Here he encounters the Naga prince Sankhachuda and learns the terrible truth behind the serpent race’s suffering.

Every day, a Naga must be offered as a sacrifice to Garuda, the mighty eagle of the gods and eternal enemy of the serpents. Garuda’s voracious hunger is appeased only by these offerings, and the Nagas have accepted this fate with sorrow but resignation. It is a cycle of fear and inevitability, one that has gone on for ages. Jimutavahana is shaken by this revelation. The idea of an entire race living under the shadow of daily death deeply disturbs him.

Meanwhile, in the same region, Jimutavahana encounters Malasena, a Naga maiden of exceptional grace. Their interaction is tender and mutual affection develops, leading to their marriage. But even in this union, the play never descends into pure romance. The marriage functions as a contrast: while he is granted love and happiness, Jimutavahana is also drawn closer to the suffering of her people.

Soon after, Jimutavahana learns that the next sacrifice is scheduled for the following day. The chosen victim is Shankhachuda, a young Naga who is deeply loved by his family. His mother’s grief and helplessness amplify the tragedy of the cycle. The emotional weight of this scene is crucial: Harsha wants the audience to feel the despair of the Nagas and the injustice of a fate that crushes the innocent.

At this point, Jimutavahana makes a decision that transforms the entire narrative. He chooses to offer himself in place of the Naga victim. His reasoning is simple but heroic: he cannot bear to witness suffering when he has the power to prevent it. Jimutavahana’s choice reflects a deeply Buddhist ethic — the bodhisattva ideal of giving one’s life to save others. This is a radical break from the typical Sanskrit dramatic hero, who might fight, flee, or negotiate, but rarely sacrifices himself willingly.

Jimutavahana goes to the sacrificial site, a seaside cliff where Garuda descends to claim his offering. He lies down on the sacrificial stone, awaiting the eagle’s arrival. Harsha skillfully heightens the tension by delaying Garuda’s descent and letting the audience absorb the gravity of Jimutavahana’s decision.

When Garuda arrives, the confrontation is brief but powerful. Jimutavahana does not resist or flee. Garuda, unaware that the man before him is not the actual Naga victim, attacks him. The scene is dramatic, filled with the violence of claws, wind, and divine force. Jimutavahana is gravely injured, nearly dying under Garuda’s assault.

However, Garuda eventually realizes the truth — this is no Naga but a human prince who offered himself voluntarily. Shocked by such unimaginable compassion, Garuda stops the attack. Harsha portrays this moment not as Garuda’s defeat but as his transformation. The divine bird is moved by Jimutavahana’s selflessness and feels remorse for causing pain to such a noble being.

Garuda then decides to end the cycle of sacrifice altogether. He promises that no Naga will ever again be taken as an offering. The curse that had haunted the serpents is lifted. The suffering race is finally freed — not by war, negotiation, or divine intervention, but by the act of one man willing to die for strangers.

Jimutavahana, however, is on the brink of death. Here Harsha reintroduces the play’s spiritual dimension. The bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, invoked in the opening benediction, now intervenes. Divine grace restores Jimutavahana to life, symbolizing the triumph of compassion, not just moral but cosmic. The universe responds to sacrifice with restoration.

The play concludes with reunion and relief. The Nagas rejoice, Jimutavahana is healed, and his heroic act becomes a moral anchor for everyone present. His father, Malasena, and the Naga community all recognize that Jimutavahana has changed the destiny of an entire race through one unparalleled act of goodness.

Nagananda ends not with conquest, marriage triumph, or political resolution — the usual endings in classical Sanskrit drama — but with a spiritual victory. It celebrates compassion as the highest human virtue and positions self-sacrifice as a form of divine strength. Jimutavahana’s heroism is quiet, moral, and transformative: he is a ruler not by power, but by ethical greatness.

Through this play, Harsha makes a philosophical statement:

Real joy — the true “Nagananda” — arises not from pleasure or victory, but from saving others, alleviating suffering, and living with absolute selflessness.

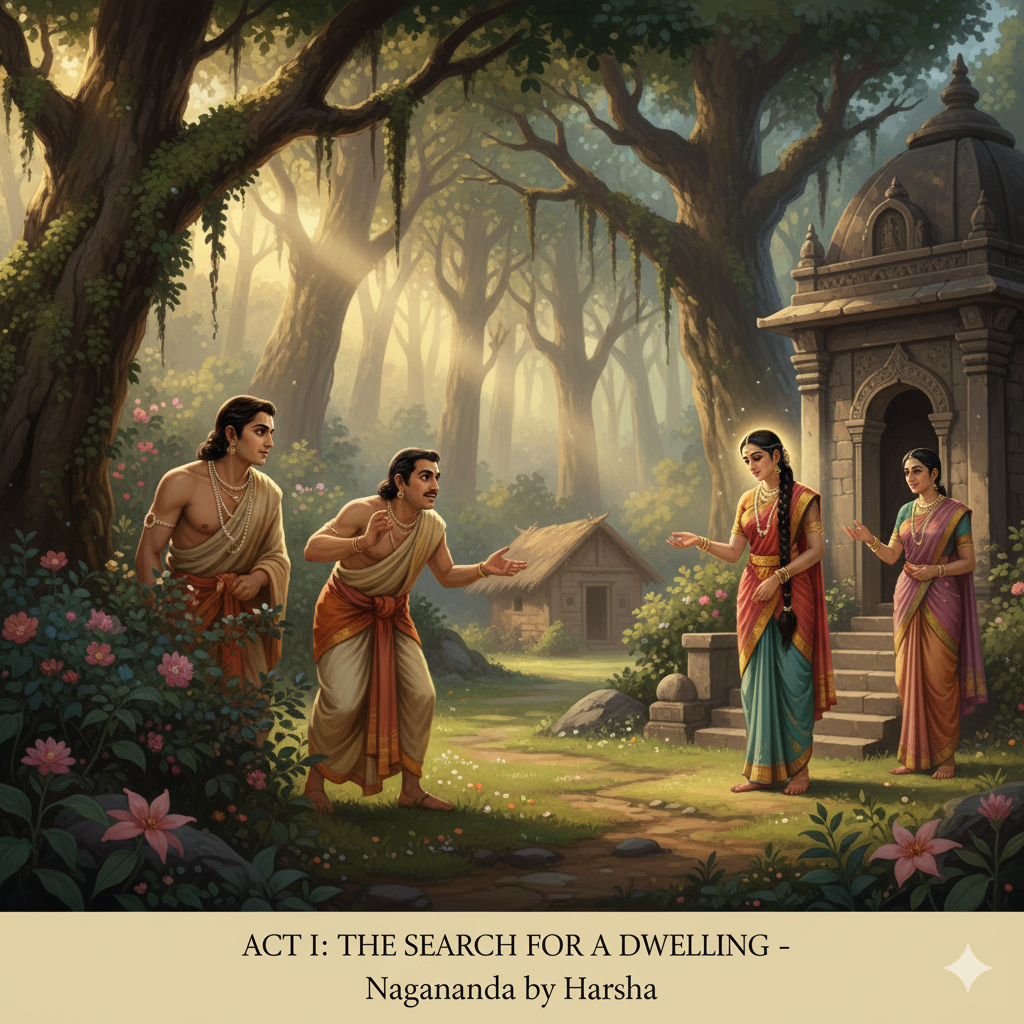

ACT I — The Invocation, Setting, and Introduction of Jimutavahana

The play opens with a Benediction to Avalokitesvara, the Buddhist Bodhisattva of compassion. This is a major departure from classical Sanskrit drama, which typically invokes Hindu deities. Harsha signals that this drama is about compassion above all else.

We move to the serene Malaya Mountain, filled with hermitages, ascetics, and natural beauty. Two Vidyadhara maidens enter, describing the peaceful environment and setting the spiritual tone. Their conversation introduces Jimutavahana, prince of the Vidyadharas, who has renounced worldly pleasures and ambition. He now lives among sages, practicing humility and compassion.

Jimutavahana enters with his father Jimuta-Ketu, speaking openly of his desire to live a righteous life. His father encourages him, proud of his virtues. Soon, attendants bring news of a group of Nagas living nearby in mourning, but the reason is not yet revealed. The tension of the unseen suffering begins here.

The Act closes with the introduction of Malasena, the Naga princess, who becomes drawn to Jimutavahana. Their interaction hints at mutual admiration, laying the groundwork for the play’s emotional core.

Act I: The Search for a Dwelling

Title: The Quest for a Dwelling (or The Discovery of Love)

The first act of Nagananda serves primarily to introduce the main characters, establish the play’s serene setting, and, crucially, ignite the central romantic subplot.

🏞️ Setting the Scene

The scene opens in a peaceful penance grove (Tapo-vana) on the slopes of the Malaya Mountains. This location is near the temple of the Goddess Gauri. The atmosphere is one of tranquility, piety, and natural beauty—a perfect backdrop for the ascetic ideals of the protagonist.

🤴 Jimutavahana’s Renunciation and Idealism

The hero, Jimutavahana, Prince of the Vidyadharas, enters with his close friend, the Vidushaka (clown) Atreya.

Jimutavahana immediately establishes his character through his words and actions:

Filial Piety: He explains that he has completely renounced his vast, beautiful kingdom—the “Vidyadhara-Cakra”—and all its riches. His sole purpose now is to serve his aging, blind parents. He views this act of filial duty as the highest form of virtue, dismissing material wealth and power.

The Search: They are currently searching for a secluded, tranquil place on the Malaya Mountains where his parents can live comfortably in retirement and continue their penance (tapas).

Dismissal of Danger: Atreya, the Vidushaka, warns Jimutavahana that by abandoning his throne, he has left his realm vulnerable to the enemy king, Matanga, who is reportedly seizing control. Jimutavahana is unperturbed. He states that he is willing to give up the kingdom to Matanga if it means avoiding conflict and remaining devoted to his higher duty. His priority is ethical conduct over material acquisition.

🎶 The Appearance of Malayavati

The Vidyadhara Prince and Atreya overhear the beautiful singing of a young woman. Jimutavahana, intrigued, instructs Atreya to investigate. They hide in the grove near the Gauri temple.

The woman is Malayavati, a Princess of the Siddhas (another class of celestial beings), accompanied by her maids.

The Prophecy: Malayavati has just received a special blessing from the Goddess Gauri. Her maid reveals the prophecy: Malayavati is destined to marry the Emperor of the Vidyadharas.

The Unspoken Meeting: Jimutavahana, who is indeed the rightful Emperor of the Vidyadharas, and Malayavati see each other for the first time. They are instantly and deeply struck by each other’s beauty—an immediate, mutual love at first sight (Pūrvānurāga).

Embarrassment and Departure: Malayavati, overwhelmed by the intensity of the unknown man’s gaze and the sudden realization of her feelings, quickly departs, leaving her companions and Jimutavahana’s party to follow.

✨ Conclusion of Act I

The act concludes with Jimutavahana and Atreya discussing the prince’s overwhelming love for the mysterious girl.

Jimutavahana, the prince who had no attachment to his kingdom or power, now finds his mind fully captured by the princess. This establishes the tension between his ascetic ideals (renunciation) and the pull of worldly desire (love).

The seeds of the Śṛṅgāra rasa (romantic sentiment) are fully sown, setting the stage for the next act’s pursuit of love, which will later be dramatically contrasted with the main Karuṇa rasa (compassionate/pathetic sentiment) of the final acts.

The primary function of Act I is to successfully transition Jimutavahana from a purely duty-bound ascetic to a man simultaneously devoted to love and self-sacrifice.

ACT II — Jimutavahana Meets the Naga Community and Learns the Truth

This Act shifts toward the tragedy concealed beneath the peaceful forest.

A group of Nagas enters, weeping and lamenting the fate of Shankhachuda, a young Naga chosen as the next sacrifice to Garuda, the divine eagle who demands a daily serpent offering. The suffering of the Naga race is laid bare — they live in constant fear, losing one loved one after another to this ancient curse.

Jimutavahana encounters Shankhachuda’s mother, who is devastated. Through her sorrowful narrative, Jimutavahana finally learns the full truth:

Every day, one Naga must die to satisfy Garuda. Today, it is her son.

This revelation deeply affects Jimutavahana. She describes the agony of countless mothers who have watched their children taken, and Shankhachuda himself enters, frightened but resigned.

Jimutavahana’s compassion becomes active here. He begins to wrestle internally with the unbearable injustice of the situation.

The Act ends with Jimutavahana deciding that he cannot allow this sacrifice to continue, and his resolve begins to form.

💖 Act II: Love and Confirmation

Title: The Unfolding of Affection (or The Discovery of Identity)

The second act of Nagananda focuses entirely on resolving the romantic tension established in Act I, allowing the primary love match to be secured before the introduction of the heroic plot in the later acts. The scene is typically set in a beautifully decorated apartment or resting place for the princess on the Malaya Mountains.

😩 Malayavati’s Distress

The act opens, focusing on Malayavati. Since the encounter in the grove, she has been consumed by thoughts of the handsome stranger she saw.

Love Sickness: She displays the classic symptoms of viraha (separation-in-love) or manmathāvasthā (love sickness). She is pale, restless, and unable to find joy in her surroundings or activities.

The Fear of Unrequited Love: She confides in her maid, wondering if the prince felt the same attraction, or if her intense passion is one-sided and therefore foolish. She expresses regret for leaving the grove so quickly.

Contemplation of Suicide: In a dramatic moment common in Sanskrit drama, she is so distressed by the uncertainty of her love that she considers ending her life, perhaps by hanging herself with a creeper vine. Her maid intervenes and attempts to comfort her.

🎨 The Portrait and Jimutavahana’s Arrival

To occupy herself, Malayavati tries to draw a picture of the object of her affection. She completes a portrait of the prince, capturing his image from memory.

Jimutavahana’s Entrance: Meanwhile, Jimutavahana and the Vidushaka Atreya enter the scene. Jimutavahana is desperate to see Malayavati again.

The Discovery of the Portrait: Jimutavahana finds the apartment empty but spots the portrait. Seeing his own image drawn by her hand, he is overjoyed. This provides definitive proof that her feelings mirror his own, confirming the Pūrvānurāga they shared.

Jimutavahana’s Portrait: Filled with excitement, Jimutavahana quickly uses a brush to draw Malayavati’s portrait next to his own on the same panel.

🎭 The Comic Mishap

Malayavati returns to the room just as Jimutavahana is finishing. She mistakes him for the Vidushaka (Atreya) and, assuming the clown has defiled her painting, expresses anger and attempts to wipe the new portrait away.

The Reveal: Jimutavahana quickly steps forward and reveals his true identity.

Joy and Embarrassment: Malayavati is overcome with joy that the man she loves is actually present, but she is also intensely embarrassed by her mistaken outburst. Jimutavahana playfully reassures her of his devotion.

🤝 The Marriage Agreement

The romance is quickly elevated to a formal agreement through the entrance of Malayavati’s brother, Mitravasu.

Mitravasu’s Confirmation: Mitravasu had been observing the events. He recognizes Jimutavahana’s noble, ascetic virtues and his high Vidyadhara status. He also remembers the prophecy of the Goddess Gauri.

Family Approval: Convinced that Jimutavahana is the ideal match, Mitravasu gives his formal consent to the union.

Conclusion: The act ends on a high note of Śṛṅgāra rasa (romantic bliss). The barriers to the lovers’ union have been removed, the identity has been confirmed, and the families have formally consented to the marriage. The love match is successfully secured, paving the way for the dramatic action concerning duty and sacrifice that begins in the next act.

ACT III — The Marriage and the Moral Turning Point

The third Act offers emotional contrast: love and joy on one side, the shadow of impending sacrifice on the other.

Jimutavahana and Malasena marry in a gentle and beautiful ceremony that emphasizes spiritual rather than sensual union. The marriage introduces warmth and stability — strengthening the stakes of Jimutavahana’s later decision.

After the wedding, however, Jimutavahana is reminded of the Naga mother’s grief. While walking with Malasena, he hears distant cries and learns that preparations for Shankhachuda’s sacrifice have begun.

This moment becomes the spiritual turning point of the play.

Despite being newly married and deeply loved, Jimutavahana feels an even deeper obligation to universal compassion. He decides he will give his own life in place of Shankhachuda.

He does not consult his father or wife — not out of secrecy, but because the decision is entirely internal and ethical. His marriage makes the sacrifice harder, but also more heroic.

The Act ends with Jimutavahana quietly leaving to prepare for the ultimate act of compassion.

👑 Act III: The Wedding and Renunciation

Title: The Conflict of Duty (or The Kingdom Refused)

The third act of Nagananda serves as the crucial pivot point in the play. It begins by celebrating the successful romance and then sharply shifts the focus from Śṛṅgāra rasa (romantic sentiment) to the core themes of Vīra rasa (heroism) and Śānta rasa (peace/renunciation), setting up the final sacrificial climax.

💍 The Celebration of Union

The act opens with the marriage of Jimutavahana and Malayavati having just taken place.

Conjugal Bliss: The setting is joyous and celebratory, reflecting the fulfillment of the romantic plot from the previous two acts. Jimutavahana and Malayavati express their happiness and profound satisfaction in their union.

The Parents’ Blessing: The focus is on the contentment of Jimutavahana’s parents, who are happy to see their son married, even though he has already given up his kingdom to pursue a life of piety and service to them.

⚔️ The Intrusion of Conflict

The mood of domestic tranquility is abruptly broken by the arrival of Mitravasu (Malayavati’s brother) and Jimutavahana’s general.

The News of Invasion: Mitravasu brings grave, urgent news. As Jimutavahana had forsaken his throne to pursue duty to his parents, the rival king, Matanga, has seen an opportunity. Matanga has successfully invaded and seized the entire Vidyadhara kingdom.

The Call to Arms: Mitravasu and the general implore Jimutavahana to act immediately. They argue that Jimutavahana is the rightful king and must lead his loyal troops to battle to reclaim his ancestral land and protect his subjects. This is presented as his Kshatriya-dharma (duty of a warrior/king).

🙅 The Refusal of the Kingdom

Jimutavahana’s response to the crisis is the defining moment of this act, demonstrating his ultimate commitment to compassion and non-violence, the core of his heroic nature.

Rejection of Materialism: Jimutavahana firmly refuses to fight. He dismisses the kingdom as fleeting and trivial, a mere “piece of earth” or a “blade of grass.”

Commitment to Non-Violence: He declares that he has taken an oath to renounce worldly possessions and, more importantly, to pursue compassion and prevent harm (Ahimsa). To wage war, even for a just cause, would violate this higher spiritual duty.

The Higher Ideal: He asserts that the true ‘fruit’ of his life lies not in securing a kingdom but in alleviating suffering and upholding morality. He states that he is prepared to allow Matanga to take the throne, preferring to live ascetically rather than cause bloodshed.

✨ Conclusion: The Shift

The act concludes with Jimutavahana successfully overcoming the temptation of power and the duty of a king, cementing his role as a Bodhisattva-like hero committed to universal welfare. The initial romantic plot is settled, and the main sacrificial plot is now prepared to begin, as Jimutavahana and his party prepare to leave the Malaya Mountains for the seashore, where the scene for the great sacrifice is set.

ACT IV — The Sacrifice: Jimutavahana Faces Garuda

This is the dramatic peak of the play.

Jimutavahana walks alone to the rocky cliff where the sacrifices take place. The ocean roars below; storm clouds gather — nature reflects the gravity of the moment.

He lies down willingly on the sacrificial stone slab, placing his body where Shankhachuda should have been. His expression is peaceful, almost meditative.

Soon, Garuda descends — a massive, divine, awe-inspiring bird. Garuda sees the figure on the stone and assumes he is the Naga victim. He swoops down with fierce speed and strikes Jimutavahana with claws and beak.

Jimutavahana makes no attempt to flee or resist. His quiet endurance shocks the audience and symbolically confronts divine violence with human compassion.

As Garuda wounds him, blood flows and the prince weakens. The moment Garuda realizes the victim is not a Naga, but a man who offered himself voluntarily, everything changes.

Garuda is struck with astonishment, then shame, then reverence.

Moved by Jimutavahana’s incomparable sacrifice, Garuda declares:

No Naga will ever again be required as a sacrifice. The cycle ends today.

This is the moral triumph of the play — compassion conquers ancient hostility.

The Act closes with Jimutavahana near death, Garuda promising to seek divine help, and the Nagas rushing to the scene in grief and awe.

🐍 Act IV: The Sacrifice

Title: The Supreme Act of Compassion (or Jimutavahana’s Offering)

Act IV is the climax of Nagananda and the emotional centerpiece of the play. It transitions fully from the romantic and political themes into the heroic and religious theme of self-sacrifice and cosmic compassion (Karuṇaˉ rasa).

🌊 The Desolate Setting

The scene shifts dramatically from the serene Malaya Mountains to a grim, desolate, rocky seashore cliff. This is the Sacrificial Stone, the designated spot where the mighty bird Garuda comes daily to devour a Naga (serpent) victim.

The Evidence of Death: Jimutavahana and his companion, likely Atreya or Mitravasu (who are later seen trying to find him), arrive at the spot. Jimutavahana immediately notices a gruesome sight: a massive pile of glistening Naga bones.

Learning the Truth: He learns from a local ascetic or traveler that this spot is the place of the daily sacrifice. Garuda, empowered by a divine boon, had been indiscriminately slaughtering the entire Naga race. To save his people from total annihilation, the Naga King Vasuki established a peace treaty, agreeing to provide one Naga daily as a sacrificial meal.

😢 The Encounter with the Naga Mother

As Jimutavahana contemplates the immense suffering of the serpents, he hears heart-wrenching wails.

The Grieving Family: He sees an old Naga mother weeping uncontrollably, accompanied by her young son, Shankhachuda, the victim chosen for that day’s sacrifice.

The Mother’s Despair: The mother’s grief is overwhelming. She laments the fate of her noble son and the ancient suffering of her race. Her son is resigned, ready to face his fate for the sake of his community, yet he still seeks comfort.

🙏 The Decision to Sacrifice

Jimutavahana, witnessing this scene of profound sorrow, is struck by an ultimate wave of compassion (daya).

The Bodhisattva Ideal: He realizes that his purpose in life is not merely passive renunciation but active intervention to alleviate suffering. He resolves that his body, which he holds as merely a perishable vessel, will serve the highest possible purpose: saving a life.

The Plan: He devises a plan to substitute himself for the young Naga prince, without the knowledge of his family or the Nagas.

Shankhachuda’s Absence: Shankhachuda requests a few moments to offer his final prayers to the Lord Avalokitesvara (the Buddhist deity of compassion, often associated with Jimutavahana’s principles) at a nearby shrine.

🩸 The Offering

While Shankhachuda is away, Jimutavahana executes his plan:

Preparation: He dons the red sacrificial robe and places the characteristic Naga crest jewel on his head, making himself appear to be the designated serpent victim.

Lying on the Stone: He lies down willingly on the sacrificial slab, calm, fearless, and serene, prepared for death. His spirit is utterly free of regret or fear.

🦅 Garuda’s Descent and the Strike

The Arrival: The gigantic, mighty bird Garuda descends from the sky, appearing enormous and powerful, casting a terrifying shadow.

The Mistake: Garuda, seeing the red robe and the Naga crest on the slab, immediately seizes the victim. He does not notice the difference between a serpent and a human due to the disguise and his haste.

The Fierce Attack: Garuda strikes Jimutavahana fiercely with his beak and claws. The prince’s body is pierced and bleeding, but he remains silent and unmoving, determined not to cry out and alert the others until the act is complete.

Garuda’s Flight: Believing he has successfully claimed his meal, Garuda lifts the injured body of Jimutavahana and flies off to his cave.

😨 The Aftermath

Shankhachuda’s Return: Shankhachuda returns from the shrine and finds the sacrificial slab empty, covered only in blood and the scattered pieces of the broken Naga crest jewel (which Jimutavahana had worn).

The Shocking Realization: He realizes that someone, another hero, has sacrificed himself in his place. He then sees the trail of blood leading away and, struck by grief and gratitude, resolves to follow the eagle to the death site to give thanks to the self-sacrificer.

The act ends on a cliffhanger, with Jimutavahana presumed dead, setting the stage for the revelation and ultimate divine intervention in Act V.

ACT V — Divine Intervention and Restoration

The final Act completes the spiritual arc of the drama.

Garuda, overwhelmed by Jimutavahana’s nobility, appeals to the heavens. This summons Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisattva invoked in the opening benediction. The deity appears as a serene, radiant figure in the sky.

Avalokitesvara blesses Jimutavahana’s sacrifice and restores him to life, symbolizing the Buddhist ideal:

Compassion, when carried to its highest form, transcends death itself.

The Naga community rejoices. Shankhachuda and his mother fall at Jimutavahana’s feet, overwhelmed with gratitude.

Malasena and Jimutavahana’s father arrive, horrified at what nearly happened but proud of his moral greatness.

The curse is broken. Garuda departs in humility and respect.

The play ends with universal relief, joy, and recognition that Jimutavahana’s act has liberated an entire race. Theworld of Nagananda is restored not through war, but through selfless love.

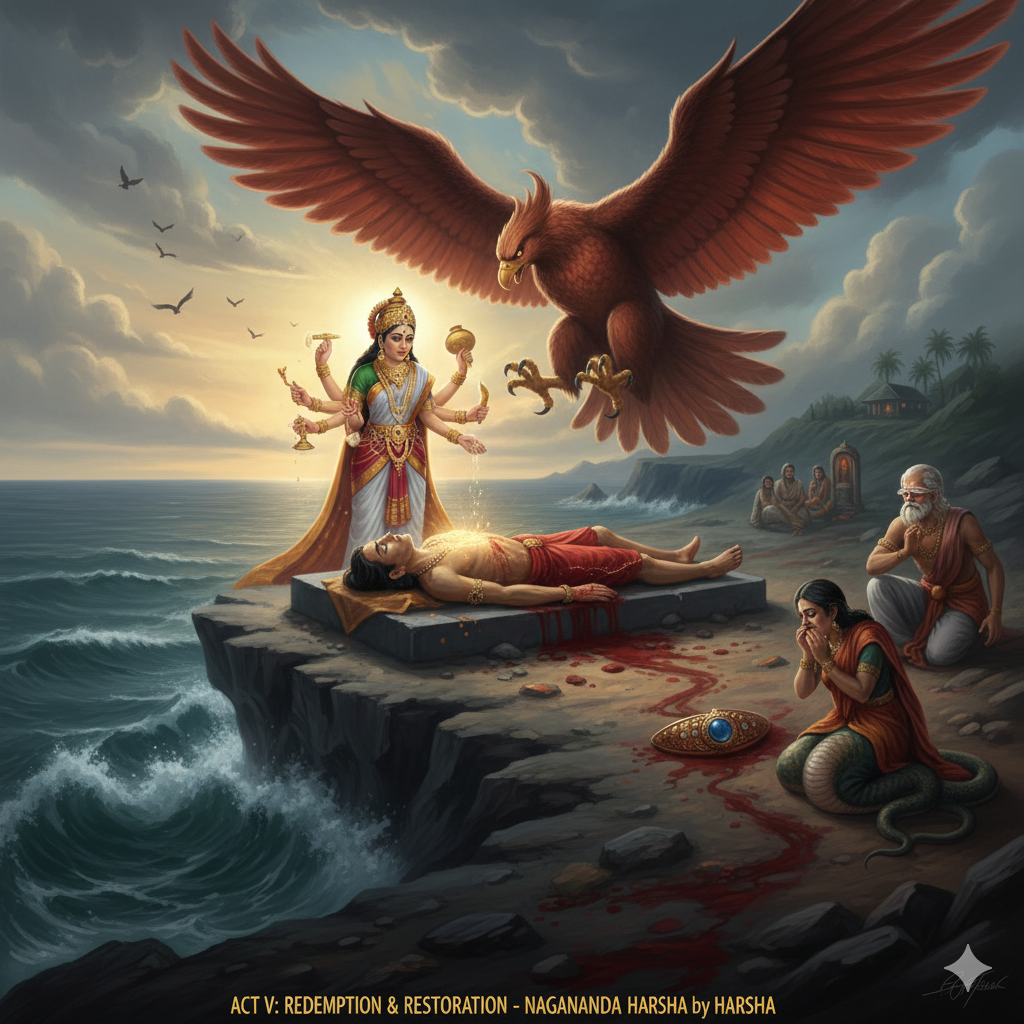

🕊️ Act V: Redemption and Restoration

Title: The Restoration by Gauri (or The Triumph of Compassion)

Act V of Nagananda provides the resolution to the central conflict, restoring the hero and establishing the lasting triumph of his selflessness, aligning with the Buddhist concept of the Bodhisattva ideal. The act shifts the sentiment from profound sorrow and sacrifice (Karuṇaˉ rasa) to astonishment, peace, and ultimate joy (Adbhuta/Sˊaˉnta rasa).

🦅 Garuda’s Remorse

The act begins at Garuda’s lair or the sky immediately after the attack, where he has carried the body of Jimutavahana.

The Discovery: Garuda, about to consume his prey, notices the body is not a snake but a human. He sees the distinctive red robe of a heroic ascetic and the remnants of Jimutavahana’s noble ornaments.

The Realization: Garuda realizes he has killed an innocent, non-Naga being who offered himself in place of the serpent. He understands the profound compassion that motivated the act.

Profound Regret: Garuda is instantly filled with deep remorse and guilt (Jugupesˊaˉ). He reflects on his own violent, predatory nature and confesses his sin. He laments the killing of such a virtuous person, whose sacrifice surpasses any act of earthly heroism.

😢 The Gathering of Grief

Jimutavahana’s family and the Nagas arrive at the scene of the sacrifice, following the trail of blood and the distressed Shankhachuda:

Malayavati’s Distress: Malayavati and Jimutavahana’s aged parents arrive and witness the severely injured, bloodied body of Jimutavahana. The grief of the wife and parents is unbearable and fills the scene with tragedy.

Malayavati’s Vow: In her despair, Malayavati prepares to commit sati (ritual self-immolation) by climbing onto the funeral pyre being prepared for her husband.

The Naga’s Confession: Shankhachuda and the Naga Mother arrive and confess to the family that Jimutavahana sacrificed himself for them, explaining the entire story to the grieving parents.

🙏 The Vow and the Divine Intervention

Seeing the immense suffering caused by his actions and understanding the divine magnitude of Jimutavahana’s benevolence, Garuda takes a vow:

Garuda’s Promise: Garuda publicly swears that, from that day forward, he will never again eat a Naga or any other creature. He vows to renounce his predatory life and henceforth only sustain himself on water, flowers, and fruits, dedicating himself to virtue.

The Appearance of Gauri: Just as Malayavati is about to step onto the pyre, the goddess Gauri (who blessed Malayavati in Act I and witnessed the heroic deed) appears. Her presence brings a calm, divine light to the scene.

The Restoration: Gauri praises Jimutavahana’s unparalleled selflessness and compassion, declaring that such an act of daya (mercy) and ahimsa (non-violence) must not be allowed to end in tragedy. She sprinkles the sacred waters from her holy vessel onto Jimutavahana’s body.

✨ Conclusion and Harmony

Jimutavahana’s Revival: Jimutavahana is instantly restored to life, his injuries healed, and he rises as if from sleep, looking refreshed and radiating light.

The Kingdom Restored: Gauri grants him a final boon: she restores his lost Vidyadhara kingdom, which he can now rule peacefully, having secured it not by violence but by supreme merit.

Universal Peace: The act concludes with the reunion of Jimutavahana with his family, the Nagas freed from their long-standing terror, and Garuda embarking on a new life of virtue. The play ends with a final blessing of universal peace and the triumph of compassion over destiny.

THEMES OF NAGANANDA

1. The Supreme Power of Compassion

The central theme of Nagananda is compassion as a transformative force. Jimutavahana’s willingness to sacrifice his own life for the Nagas embodies the highest form of human virtue. Harsha elevates compassion above heroism, strength, or even divine authority. The play opens with an invocation to Avalokitesvara — the Bodhisattva of compassion — signaling that empathy, not power, drives this universe. Compassion is not passive pity; it is decisive moral action.

2. Self-Sacrifice as the Highest Heroism

Unlike most Sanskrit plays where heroes win through courage, intelligence, or divine intervention, Jimutavahana’s greatness comes from self-offering. He represents the bodhisattva ideal — one who willingly suffers for the good of others. His sacrifice ends centuries of Naga oppression. Harsha asserts that the noblest victories are moral, not martial.

3. The Suffering of the Innocent

The Nagas’ predicament — forced to lose one member daily to Garuda — highlights systemic suffering. Innocent beings face death without cause. Their sorrow, especially that of Shankhachuda’s mother, personalizes a tragedy that might otherwise feel abstract. This theme drives the narrative: Jimutavahana cannot remain a witness to injustice.

4. Dharma and Moral Duty

Dharma (righteousness) in Nagananda is not limited to ritual or tradition; it is ethical responsibility. Jimutavahana believes that privilege demands sacrifice, not comfort. His duty is self-chosen and grounded in empathy. Harsha subtly critiques passive interpretations of dharma by showing that true righteousness requires courage.

5. The Transformation of Power Through Virtue

Garuda symbolizes overwhelming power, violence, and divine authority. Yet his power bows before human virtue. When he realizes Jimutavahana’s sacrifice, Garuda abandons aggression and becomes an agent of protection. This reversal suggests that moral strength can transform even the fiercest divine forces.

6. Love and Emotional Bonding

Jimutavahana’s marriage to Malasena is gentle, not dramatic. Their bond emphasizes tenderness, loyalty, and shared values. His choice to sacrifice himself after marriage — aware of the pain it will cause her — deepens the emotional weight of his decision. Love does not weaken Jimutavahana; it elevates his sacrifice.

7. The Victory of Spiritual Ideals Over Violence

Nagananda is unusual among Sanskrit plays because the climax is not a battle but a refusal to fight. Violence is stopped not by counter-violence, but by self-giving love. The world is saved not by weapons, but by moral courage. Harsha argues that spiritual ideals are stronger than physical might.

8. Divine Grace and Cosmic Order

Avalokitesvara’s appearance in the final act shows that the universe responds to selfless virtue. Divine intervention does not precede sacrifice — it rewards it. This affirms a moral cosmos: the universe bends toward righteousness. Jimutavahana’s resurrection symbolizes the alignment of human virtue and divine will.

9. Human Emotions as Moral Catalysts

The Naga mother’s grief is not just emotional ornamentation — it becomes the catalyst for Jimutavahana’s decision. Harsha uses human emotions to shape ethical action. Compassion begins with feeling another’s suffering and culminates in transformative deeds.

10. Liberation and the Ending of Cycles

The daily sacrifice to Garuda represents a cycle of inherited suffering. Jimutavahana’s intervention breaks this pattern permanently. Liberation in Nagananda is not individual but collective — the entire Naga race is freed through one act of extreme goodness.

CHARACTERS OF NAGANANDA WITH DETAILED ANALYSIS

1. Jimutavahana (Protagonist)

Role: Prince of the Vidyadharas; moral center of the play

Character Analysis:

Jimutavahana is one of the most unique heroes in Sanskrit literature. Unlike the warriors of Kalidasa or the political strategists of Vishakhadatta, Harsha creates a hero whose power is purely ethical. His strength lies not in combat, intelligence, or royal command but in compassion, self-sacrifice, and moral clarity.

He renounces worldly pleasures and embraces a life of service, symbolizing the bodhisattva ideal. His decision to offer himself in place of the Naga prince is not impulsive heroism; it is a conscious act rooted in empathy. His marriage to Malasena deepens his humanity — he sacrifices his life knowing exactly what personal happiness he will lose. Jimutavahana proves that true greatness is measured not by conquest but by selflessness. His resurrection at the end affirms the supremacy of virtue in the cosmic order.

He is the compassionate heart of Nagananda and Harsha’s model of moral kingship.

2. Malasena (Heroine)

Role: Naga princess; wife of Jimutavahana

Character Analysis:

Malasena is not a dramatic heroine in the traditional sense — she neither creates conflict nor resolves it. Her importance lies in what she represents: love, tenderness, and the emotional life that Jimutavahana must relinquish for his greater moral duty.

Her loving relationship with Jimutavahana humanizes the otherwise saint-like hero. She symbolizes the intimate joys he willingly sacrifices. Malasena’s grief and innocence heighten the tragic tension. Through her, Harsha shows that moral greatness is never easy — it demands a price. Malasena stands as a soft reminder of what is lost when virtue requires self-renunciation.

3. Shankhachuda (The Young Naga Prince)

Role: The intended sacrificial victim

Character Analysis:

Shankhachuda embodies innocence and vulnerability. He is not heroic in the traditional sense, nor is he meant to be. Instead, he is the catalyst — his suffering awakens Jimutavahana’s deepest compassion.

His fear, dignity, and acceptance of fate reveal the cruelty of the ancient cycle of daily serpent sacrifices. He represents all oppressed beings who suffer not because of personal fault, but because fate placed them in a vulnerable community. Shankhachuda’s life — spared through Jimutavahana’s sacrifice — becomes the symbol of liberation for the entire Naga race.

4. Shankhachuda’s Mother

Role: The grieving Naga mother

Character Analysis:

Her character is one of Harsha’s most emotionally powerful creations. She gives the injustice of the serpent sacrifice a human face. It is through her grief that Jimutavahana learns the depth of the Nagas’ suffering. Her role is brief but unforgettable — her sorrow drives the moral engine of the story.

She represents the pain of generations who lived under oppression. Through her, Harsha emphasizes that compassion often begins when one witnesses another’s devastation.

5. Jimuta-Ketu

Role: Jimutavahana’s father

Character Analysis:

A wise, elderly king who has stepped back from active rule. He supports his son’s spiritual pursuits and recognizes Jimutavahana’s moral greatness. His presence adds emotional weight, especially in the final act, where he confronts the near loss of his son.

Jimuta-Ketu symbolizes ideal kingship — a ruler who values righteousness over power and accepts the cost of virtue when practiced by his own child.

6. Garuda

Role: Divine eagle; antagonist turned protector

Character Analysis:

Garuda begins as a terrifying force — divine, immense, and bound by ancient hostility towards the serpent race. He represents violence, instinct, and the inevitability of suffering within cosmic cycles.

But Garuda’s transformation is one of the play’s most profound moments. When he discovers that Jimutavahana willingly offered himself, Garuda’s aggression melts into reverence. His remorse leads him to abolish the sacrifice forever. In this sense, Garuda becomes a symbol of power humbled by virtue. He illustrates Harsha’s message that even divine forces can be transformed by human goodness.

7. Avalokitesvara (Bodhisattva)

Role: Divine figure who restores Jimutavahana

Character Analysis:

Avalokitesvara frames the entire play — invoked in the beginning and appearing at the climax. His presence emphasizes the Buddhist influence and sanctifies Jimutavahana’s sacrifice.

He represents cosmic approval of compassion.

His intervention shows that the universe itself bends toward selflessness. Avalokitesvara’s final act — restoring Jimutavahana to life — symbolizes that moral virtue transcends death.

8. Attendants, Vidyadhara Maidens, Hermits

Role: Supporting characters who establish atmosphere

Character Analysis:

These characters enrich the dramatic world:

Vidyadhara maidens introduce the audience to the serene and sacred environment.

Hermits represent the spiritual purity of the Malaya mountain.

Attendants serve to highlight Jimutavahana’s noble decisions and provide transitions.

They collectively create a world where spirituality and compassion dominate, not politics or warfare.

OVERALL CHARACTER STRUCTURE

Nagananda is unusual because:

The hero is moral, not martial.

The villain becomes transformed, not defeated.

The female characters humanize the ethical choices rather than drive plot conflict.

The divine character restores, not punishes.

Harsha constructs a universe where compassion is the highest form of power, and every character contributes to that moral architecture.

Critical Appreciation of Nagananda by Harsha

Nagananda is the rare Sanskrit drama that combines moral intensity with theatrical grace. At once devotional and dramatic, it refuses easy classification: not a political play, not a mere romance, and not simple religious propaganda. Harsha composes a work that is formally classical and ethically radical. The play’s ambition is not to entertain only but to transform the audience’s moral imagination. It succeeds because its structure, language, and ethical center are tightly integrated.

Moral Vision and Thematic Boldness

The play’s dominant achievement is its elevation of compassion as the primary dramatic force. Jimutavahana’s self-offering is not a sentimental climax. It is a deliberate ethical act that reframes heroism. In Sanskrit drama, the heroic often means victory, prowess, or social restoration. Harsha replaces that metric with self-sacrifice. By doing so he places Nagananda closer to a moral parable than to conventional court drama. Yet the play never becomes didactic because its ethical argument grows organically from character and situation. The suffering of the Nagas is shown in human terms. The grief of Shankhachuda’s mother, the resigned dignity of the Nagas, and the quiet strength of Jimutavahana create an emotional logic that makes the sacrificial choice inevitable and morally persuasive.

Religious Syncretism and Philosophical Depth

Harsha’s invocation of Avalokitesvara signals a clear Buddhist influence, unusual in a literary culture dominated by Hindu mythic idioms. But the play is not sectarian. It blends Buddhist compassion, Hindu myth (Garuda and Nagas), and classical dramaturgy into a composite worldview. This syncretism is a strength: the drama stages universal ethical concerns rather than a narrow doctrinal dispute. The play’s philosophical achievement lies in showing how spirituality, when enacted through ethical choice, reshapes cosmic order. The appearance of Avalokitesvara at the conclusion is not a deus ex machina in the pejorative sense. It is theatrical confirmation of a moral law: the cosmos honors supreme compassion.

Characterization: Moral Types Made Human

Characters are archetypal yet emotionally real. Jimutavahana is an ethical archetype — the bodhisattva-prince — but Harsha gives him interiority: marriage to Malasena, filial ties to Jimuta-Ketu, and the strain of choosing personal happiness over universal duty. Malasena functions as more than a love interest; she humanizes the stakes and deepens the tragedy. Shankhachuda and his mother are instruments of moral awakening, but they are also vividly drawn with grief and dignity. Garuda’s arc is especially notable. Harsha resists simple demonization. Garuda is mighty and implacable, yet he is capable of moral conversion. His shift from predator to protecter dramatizes the play’s central thesis: power transformed by virtue is the highest form of authority.

Dramatic Structure and Pacing

Formally, Nagananda adheres to classical Sanskrit rules while adapting them to moral drama. The five-act structure provides room for exposition, emotional development, ethical crisis, and resolution. Harsha’s pacing is careful: the play builds sorrow before the sacrificial act so that Jimutavahana’s decision carries cumulative weight. The silence and stillness of the sacrificial sequence are theatrical masterstrokes. In staging terms, the cliff, the stone slab, and the ocean allow a visual economy that matches the drama’s moral austerity. The resurrection scene is staged with judicious restraint; divine intervention confirms rather than overwhelms human agency.

Language and Poetic Strategy

While Harsha is not Kalidasa in lyrical surplus, his language is effective for moral drama. He uses plain, dignified diction where ethical clarity is required and reserves elevated poetic moments for spiritual revelation. Imagery of light and water, of sacrifice and rebirth, is recurrent and symbolic without becoming rhetorical excess. The play’s dialogues favor moral argument and witness over rhetorical display, which helps maintain focus on ethical consequence.

Innovations and Theatrical Risks

Harsha takes risks that pay off. He centers a play on self-sacrifice at a time when kingship and courtly virtues typically celebrate conquest and display. He foregrounds a nonviolent resolution to communal suffering. Dramatically, he makes the antagonist redeemable. These choices might have alienated a courtly audience, but they instead invite reflection. Harsha’s experiment proves that theatre can be a space for ethical education, not only aesthetic pleasure.

Social and Political Resonances

The play’s release under the patronage of a king who was himself a poet and patron of letters adds political subtext. Nagananda models an ideal of kingship: the ruler as moral exemplar rather than merely a war leader. That Harsha wrote a play celebrating renunciation and compassion suggests a political imagination that values ethical authority. The play quietly critiques any social order that tolerates institutionalized suffering, using myth to reflect moral concerns relevant to governance and public ethics.

Limitations and Critical Caveats

The play’s moral clarity can feel schematic at times. Secondary characters are less developed than the ethical core demands, and some scenes function primarily as moral signposts. The resurrection motif may strike some modern readers as tidy, accidental closure. Yet these are minor reservations compared to the play’s strengths. The dramaturgy remains persuasive because the emotional arcs are earned.

Final Assessment

Nagananda stands as a distinctive achievement in classical Indian drama. Its moral seriousness, religious breadth, and theatrical discipline produce a work that is both moving and intellectually robust. Harsha demonstrates that a play can be ethically ambitious while remaining theatrically effective. The lasting power of Nagananda comes from its conviction that compassion is not a passive virtue but a decisive force able to reorder the cosmos. That conviction is staged fully and uncompromisingly, and it is what gives the play its moral authority and aesthetic depth.

STYLISTIC DEVICES IN NAGANANDA

Harsha employs a rich blend of dramaturgical techniques, poetic devices, and symbolic strategies that elevate Nagananda beyond a conventional Sanskrit play. These stylistic devices make the drama emotionally powerful and philosophically resonant.

1. Invocation (Nandi) with Buddhist Influence

Unlike most Sanskrit plays, the benediction invokes Avalokitesvara, not a Hindu deity.

Stylistic purpose:

Sets the tone of compassion

Signals the fusion of Buddhist and Hindu dramaturgy

Prepares the audience for a hero driven by self-sacrifice, not valour

It is both a structural requirement and a thematic declaration.

2. Symbolism

Symbolism shapes emotional meaning throughout the play.

Key symbols used:

Garuda → violence, divine power, and oppressive cycles

Jimutavahana → moral light, bodhisattva ideal, human compassion

Sacrificial stone slab → inherited suffering and systemic violence

Malaya mountain → spiritual refuge and inner awakening

Naga ornaments and serpent imagery → vulnerability, ancient sorrow

Avalokitesvara’s appearance → cosmic ratification of virtue

Symbolism makes abstract moral ideas visually and emotionally accessible.

3. Contrast (Virodha)

Harsha uses contrast to heighten emotional and philosophical impact.

Examples:

Compassion (Jimutavahana) vs. Violence (Garuda)

Life vs. Sacrifice

Innocence (Shankhachuda) vs. Ancient cycles of suffering

Human vulnerability vs. divine intervention

Joy of marriage vs. duty-driven renunciation

The entire play is built on moral contrast rather than conflict-driven plot.

4. Emotional Appeal (Karuna Rasa – Pathos)

Nagananda is primarily a Karuna-rasa drama.

Harsha focuses on sorrow not to depress, but to activate compassion in the audience.

The grief of Shankhachuda’s mother, the fear of the young Naga prince, and the anguish of Malasena all build emotional intensity that culminates in the sacrificial act.

Karuna rasa is the emotional engine of the play.

5. Elevated Language and Poetic Imagery

Harsha employs refined Sanskrit diction combined with poetic imagery:

metaphors of light for virtue

storm and ocean imagery for the sacrificial scene

floral and forest imagery to depict the serene hermitage

Language becomes a tool for moral persuasion and aesthetic pleasure.

6. Dramatic Irony

Dramatic irony appears during the sacrifice scene:

The audience knows that Jimutavahana is a human sacrificing himself.

Garuda initially believes he is attacking a Naga.

This tension amplifies emotional engagement and highlights the futility of violence.

7. Dialogic Moral Exposition

Characters often express ethical debates through dialogue.

These discussions serve three purposes:

Reveal character

Advance the moral argument

Prepare the audience for the climactic sacrifice

Harsha uses conversation as a philosophical instrument, not just exposition.

8. Divine Machinery (Deus ex Machina, but Purposeful)

Avalokitesvara’s appearance is a classic Deus ex Machina, but not arbitrary.

It functions stylistically to:

confirm the moral correctness of Jimutavahana’s sacrifice

restore cosmic harmony

reinforce Buddhist themes

The divine intervention completes the ethical arc rather than resolving plot inconvenience.

9. Use of Scenic Natural Imagery

Nature is not a backdrop; it mirrors the emotional climate.

Examples:

The serene Malaya mountain reflects Jimutavahana’s peace and purity.

The stormy cliff during the sacrifice represents moral crisis.

This is a stylistic blending of nature and narrative, similar to classical Indian aesthetics and Western pathetic fallacy.

10. Musicality and Lyrical Passages

Songs, verses, and rhythmic dialogues appear throughout the play.

Stylistic functions:

soften transitions

heighten emotional peaks

create spiritual mood

Harsha uses lyricism strategically, not excessively.

11. Transformation (Parivarta) as a Dramatic Device

One of the play’s strongest devices is the moral transformation of Garuda.

Stylistically, this transformation illustrates the play’s central thesis:

Virtue converts violence. Compassion reforms even divine aggressors.

Garuda’s shift from executor to protector is not just plot progression; it is a dramatic and ethical device demonstrating the power of selfless action.

12. Universality Through Minimalism in Conflict

Harsha avoids political conspiracies, court intrigues, or elaborate subplots.

This minimalism creates:

focus on moral drama

clarity of emotional progression

a universal tone applicable across cultures

This stylistic restraint makes Nagananda timeless.

13. Moral Allegory Through Drama (Upama-Alankara in Action)

Jimutavahana’s sacrifice mirrors bodhisattva tales, functioning as an extended moral allegory.

The play itself becomes an allegory about:

freedom from suffering

breaking destructive cycles

ethical kingship

the triumph of virtue

Harsha transforms myth into philosophical theatre.

Conclusion: What These Devices Achieve

Together, these stylistic devices make Nagananda:

spiritually profound

emotionally resonant

dramatically disciplined

philosophically unified

Harsha’s craftsmanship ensures that structure, language, emotion, and philosophy reinforce each other, creating a play that is both literary art and moral instruction.

TEN SHORT QUESTION–ANSWERS (2–3 lines each)

1. Who is the central hero of Nagananda, and what makes him unique?

Jimutavahana is the hero, known not for martial power but for supreme compassion. His willingness to sacrifice himself for the Naga race makes him one of the most ethically elevated heroes in Sanskrit drama.

2. What is the central conflict in Nagananda?

The Nagas must offer one life daily to Garuda, creating a cycle of suffering. Jimutavahana breaks this cycle by offering himself in place of the Naga prince Shankhachuda.

3. Why does Harsha invoke Avalokitesvara in the opening?

The invocation signals that compassion—not rivalry or conquest—guides the drama. It also infuses Buddhist ethical ideals into a classical Sanskrit framework.

4. What role does Shankhachuda play in the narrative?

Shankhachuda represents innocent suffering. His fear and helplessness move Jimutavahana to act, making him the catalyst for the hero’s moral choice.

5. How does Malasena contribute to the emotional depth of the play?

Her love for Jimutavahana humanizes him and intensifies the tragedy of his sacrifice. She symbolizes the personal loss he accepts for a greater moral duty.

6. What transformation does Garuda undergo?

Garuda shifts from a feared divine predator to a humbled protector. Jimutavahana’s sacrifice forces him to recognize the power of virtue over violence.

7. What is the significance of the sacrificial stone scene?

It marks the climax of moral heroism in the play. Jimutavahana’s calm acceptance of death dramatizes the triumph of compassion over instinctive self-preservation.

8. How does Harsha use nature to enhance the drama?

The serene Malaya forests contrast with the violent sea cliffs of the sacrifice, reflecting the emotional and moral transitions of the plot.

9. Why is Avalokitesvara’s final appearance important?

It validates Jimutavahana’s sacrifice and restores cosmic balance. Divine intervention confirms that true compassion aligns with universal law.

10. What core message does Nagananda deliver?

The play asserts that compassion is the highest form of strength. True heroism lies in selflessness, not conquest, and moral courage can transform even divine beings.

TEN 5-MARK QUESTION–ANSWERS ON NAGANANDA

1. How does Harsha portray the theme of compassion in Nagananda?

Harsha makes compassion the moral core of the play. Jimutavahana’s willingness to sacrifice himself for a race not his own reflects the bodhisattva ideal of universal empathy. This compassion is not passive; it leads to decisive action that ends the Nagas’ suffering. Even Garuda, initially a force of violence, is transformed by witnessing such selflessness. Thus, the play presents compassion as a power capable of altering cosmic order.

2. What is the significance of Jimutavahana’s sacrifice?

Jimutavahana’s sacrifice represents the highest form of dharma. Instead of heroic conquest, Harsha glorifies self-offering for the greater good. The sacrifice breaks an ancient cycle of suffering and liberates the entire Naga race. Dramatically, it is the play’s emotional and ethical peak, showing that moral courage surpasses physical strength. His later resurrection affirms the cosmic value of selfless virtue.

3. Discuss the role of Garuda in the play.

Garuda begins as a fearsome divine predator enforcing an age-old cycle of violence. However, his character undergoes a profound transformation after realizing Jimutavahana sacrificed himself voluntarily. This realization humbles him, leading him to end the sacrifice system forever. Garuda’s change highlights one of the play’s central messages: virtue can reform even the fiercest forces of nature or divinity.

4. How does Harsha use the character of Shankhachuda to build emotional depth?

Shankhachuda serves as the emotional trigger for Jimutavahana’s moral awakening. His innocence and fear personalize the suffering of the entire Naga race. By showing the child’s helplessness and the anguish of his mother, Harsha ensures that the audience understands the cruelty of the ritual sacrifice. The young prince’s plight gives the narrative its emotional urgency and makes Jimutavahana’s decision inevitable and meaningful.

5. Explain the dramatic importance of Malasena.

Malasena humanizes Jimutavahana by giving him a personal life and emotional connection. Her presence raises the stakes of his sacrifice because he willingly abandons marital happiness to uphold a moral duty. She represents love, vulnerability, and the cost of ethical choices. Dramatically, Malasena adds tenderness to the play and deepens the tragic impact of his decision.

6. How does nature function symbolically in Nagananda?

Nature mirrors the emotional and moral transitions of the play. The peaceful Malaya mountain reflects Jimutavahana’s purity and the spiritual tone of the early acts. In contrast, the stormy seashore during the sacrificial climax symbolizes conflict, crisis, and impending transformation. Harsha uses natural settings not merely as backdrop but as symbolic extensions of psychological and ethical states.

7. What role does Avalokitesvara play in the final act?

Avalokitesvara appears as the divine embodiment of compassion, validating Jimutavahana’s sacrifice. His intervention restores the prince to life, symbolizing the universe’s approval of selfless virtue. This final appearance reinforces Buddhist ethical ideals and brings cosmic closure. Avalokitesvara ensures that the play ends with harmony, liberation, and spiritual affirmation.

8. How does Harsha blend Buddhist and Hindu elements in the play?

Harsha seamlessly merges Hindu mythological characters like Garuda and the Nagas with Buddhist ethical ideals personified by Avalokitesvara. The dramatic structure follows Sanskrit conventions, but the moral philosophy leans heavily toward Buddhist compassion. This blend reflects spiritual inclusivity and shows Harsha’s intention to create a universal moral narrative rather than a sectarian one.

9. What makes Nagananda different from other Sanskrit plays?

Unlike typical Sanskrit dramas centered on romance, political intrigue, or heroic conquest, Nagananda focuses on moral heroism and self-sacrifice. The protagonist is not a warrior but a compassionate prince. The antagonist (Garuda) is not defeated but transformed. The play’s emotional core is pathos rather than triumph. This thematic and structural uniqueness gives Nagananda a spiritual depth rarely seen in classical drama.

10. Explain the significance of the mother’s grief in shaping the narrative.

Shankhachuda’s mother represents the collective suffering of the Naga race. Her grief personalizes the tragedy and brings the abstract ritual sacrifice into vivid emotional focus. Her sorrow moves Jimutavahana from passive empathy to active intervention. Harsha uses her character to highlight the emotional cost of systemic violence and to justify the moral urgency of the hero’s sacrifice.

Five Long-Answer Question–Answers (150–200 words each) on Nagananda.

Each answer is clear, analytical, and suitable for university-level exams or your website content.

1. Discuss how Nagananda presents self-sacrifice as the highest form of heroism.

In Nagananda, Harsha redefines heroism by shifting emphasis from martial valor to moral courage. Jimutavahana’s willingness to sacrifice himself for the Naga race becomes the central ethical and dramatic act of the play. Instead of achieving glory through conquest or victory, he achieves greatness through selfless offering. His choice is grounded in deep empathy, awakened by witnessing the suffering of Shankhachuda and his grieving mother. Harsha portrays sacrifice not as a tragic loss but as an ennobling act that liberates an entire community from a cruel ancient cycle. Jimutavahana’s decision carries an emotional and philosophical weight because he has every reason to choose personal happiness—he has just married Malasena, and his father depends on him. Yet he chooses the welfare of strangers over his own life. The cosmic response to his sacrifice, culminating in Avalokitesvara’s intervention, reinforces the play’s message that true heroism lies in compassion. The universe itself honors virtue above power.

2. Examine the role of Garuda and his transformation in the play.

Garuda serves as both antagonist and moral instrument in Nagananda. Initially, he represents divine authority, violence, and an unquestioned cosmic hierarchy that demands the daily sacrifice of a Naga. His ferocity highlights the magnitude of Jimutavahana’s courage. When Garuda first attacks Jimutavahana, believing him to be Shankhachuda, the hero’s calm endurance becomes the catalyst for Garuda’s transformation. Witnessing a human voluntarily submit to death for another’s sake shakes Garuda’s worldview. His shift from a fearsome predator to a remorseful, compassionate being illustrates Harsha’s central message: even forces of destruction can be transformed by moral excellence. Garuda’s decision to end the cycle of sacrifice permanently marks a crucial turning point in the play. His transformation also reflects the power of dharma when practiced with sincerity. By making Garuda capable of moral growth, Harsha shows that virtue does not simply defeat violence—it elevates and reforms it.

3. How does Harsha integrate Buddhist and Hindu elements in Nagananda, and what is the effect of this blend?

Nagananda is one of the finest examples of religious and cultural synthesis in Sanskrit drama. Harsha weaves together Buddhist compassion and Hindu mythology to create a universal message about suffering and redemption. The play’s opening benediction to Avalokitesvara immediately establishes a Buddhist ethical framework. Jimutavahana’s moral character mirrors the bodhisattva ideal, emphasizing selflessness, empathy, and the willingness to sacrifice oneself for others. At the same time, the narrative is embedded in Hindu myth: Garuda, the Nagas, and celestial races all reflect classical Hindu cosmology. This blend of traditions is neither contradictory nor superficial. Instead, it expands the moral universe of the play, showing that compassion transcends doctrinal boundaries. Harsha’s synthesis invites audiences from both traditions to recognize the shared value of moral courage. The effect is a drama that feels spiritually inclusive, philosophically rich, and culturally unified—an ethical bridge between two great traditions.

4. Discuss the emotional significance of the Naga mother’s grief in shaping the drama.

Shankhachuda’s mother represents the emotional heart of Nagananda. Her grief transforms an abstract ritual—the daily sacrifice to Garuda—into a human tragedy that the audience cannot ignore. Harsha uses her sorrow strategically to awaken both the hero’s compassion and the audience’s moral consciousness. Her lament is not exaggerated melodrama; it is a raw portrayal of generational suffering endured by the Naga race. When she reveals that her son is the next victim, the emotional intensity reaches its peak. This moment propels Jimutavahana toward his ultimate decision. Without her presence, the sacrifice would lack personal urgency. Her grief stands as a symbol of all oppressed communities whose suffering is normalized by tradition. By giving voice to the marginalized, Harsha emphasizes the ethical responsibility of those with privilege or power. The Naga mother’s role is brief but essential: she transforms Jimutavahana’s empathy into action and turns the narrative toward its moral climax.

5. Evaluate how nature is used symbolically throughout Nagananda.

Nature in Nagananda is not a passive backdrop but an active symbolic force that mirrors emotional and moral states. The play opens on the serene Malaya mountain, a place of spiritual purity, ascetic calm, and moral clarity. This peaceful setting reflects Jimutavahana’s character and the atmosphere of compassion that frames the drama. In contrast, the sacrificial cliff by the stormy sea represents conflict, fear, and the ancient cycle of violence. The rugged stones and crashing waves intensify the emotional tension of the sacrifice scene. The shift in natural setting from woodland tranquility to oceanic turmoil parallels Jimutavahana’s journey from peaceful contemplation to moral crisis. Additionally, the appearance of Avalokitesvara surrounded by celestial light symbolizes cosmic approval of virtue. Through these natural and supernatural elements, Harsha creates a landscape that responds to human action, reinforcing the play’s spiritual depth and dramatic momentum. Nature becomes a silent but powerful participant in the moral narrative.

Essay Question:

Discuss Nagananda as a unique moral and spiritual drama in Sanskrit literature. How does Harsha combine compassion, sacrifice, myth, and dramaturgy to create a play that stands apart from traditional Sanskrit theatre?

Essay Answer (900–1000 words)

Harsha’s Nagananda occupies a distinctive place in the canon of Sanskrit drama because it brings together elements rarely found in a single work: Buddhist ethics, Hindu mythology, emotional depth, and classical dramaturgical discipline. While other Sanskrit plays often explore romance, political intrigue, or heroic valor, Nagananda positions compassion as the supreme dramatic force. Harsha’s narrative unfolds not through the ascent of a warrior or the triumph of a kingdom, but through the deliberate self-sacrifice of a prince whose heroism lies in moral resolve rather than physical conquest. In doing so, Harsha constructs a drama that is spiritually potent, aesthetically restrained, and ethically radical.

At the heart of the play lies the character of Jimutavahana, the Vidyadhara prince whose life becomes a demonstration of selfless duty. His heroism challenges the traditional Sanskrit heroic ideal centered on physical might or political acumen. Instead, he embodies the bodhisattva ideal, a being who willingly accepts suffering to alleviate the suffering of others. Harsha opens the play with an invocation not to a Hindu deity, as common in Sanskrit drama, but to Avalokitesvara, the Buddhist Bodhisattva of Compassion. This surprising invocation sets the moral tone of the entire play: mercy, empathy, and spiritual generosity will be the guiding principles.

This moral universe encounters a dramatic crisis when Jimutavahana learns of the plight of the Naga community. Their race lives under the burden of an ancient curse: each day, one Naga must be offered as a sacrifice to Garuda, the powerful eagle-deity and eternal enemy of the serpents. This ritualized violence forms the central conflict of the play. Harsha does not present this suffering abstractly. Instead, he personalizes it through the introduction of Shankhachuda, a young Naga prince destined to be the next victim. His mother’s grief, expressed in raw emotional terms, becomes the emotional turning point of the drama. Through her sorrow, Harsha compels both Jimutavahana and the audience to confront the cruelty of this cosmic arrangement.

The ethical architecture of Nagananda becomes clear at this point: suffering is presented not as fate to be endured but as injustice to be corrected. Jimutavahana’s response is neither anger nor negotiation but a profound act of self-offering. His decision to substitute himself for Shankhachuda marks the moral apex of the play. This choice is rendered more powerful by the fact that Jimutavahana is newly married to Malasena, a Naga princess who represents emotional intimacy, stability, and foreseeable happiness. His sacrifice, therefore, is not the result of isolation or ascetic detachment; it is deeply costly. He relinquishes not only his life but also the personal joys that have just begun to bloom. Harsha thus elevates his sacrifice beyond a gesture of duty into an act of ethical transcendence.

The sacrificial scene by the seashore—arguably one of the most striking in all Sanskrit theatre—is a testament to Harsha’s dramatic control. The setting itself becomes symbolic: the stormy waves, the bleak rock, and the isolation of the cliff mirror the tension between cosmic violence and human compassion. Jimutavahana lies calmly on the sacrificial stone, accepting the fate intended for Shankhachuda. The arrival of Garuda, fierce and tempestuous, intensifies the scene’s dramatic energy. Initially, Garuda strikes Jimutavahana with the brutal force meant for his prey. The tension arises from dramatic irony: the audience knows that the victim is not a Naga but a human prince offering himself willingly. When Garuda eventually discovers the truth, his transformation becomes the play’s emotional and philosophical climax. Moved by the unprecedented selflessness of Jimutavahana, he abandons the ritual forever, ending the suffering of the Nagas.

This transformation is crucial. In most Sanskrit plays, antagonistic forces are defeated or outwitted. In Nagananda, the antagonist—if he can be called that—is redeemed. Garuda’s change of heart represents the triumph of virtue over violence. Harsha suggests that even divine beings, embodiments of cosmic forces, can be morally awakened. This is a radical proposition in classical theatre. By making compassion capable of transforming the cosmic order, Harsha elevates it above traditional concepts of power.

The final act’s divine intervention further deepens the spiritual dimension of the play. Avalokitesvara appears to restore Jimutavahana to life, symbolizing the cosmos’s approval of his noble act. This intervention is not merely a narrative convenience but a philosophical statement: where compassion is supreme, the universe aligns itself to protect and honor the compassionate. The resurrection, therefore, is a dramatic affirmation of the moral law Harsha constructs: selflessness does not end in loss; it culminates in spiritual victory.

Beyond thematic content, Harsha’s stylistic choices also distinguish Nagananda. His language balances poetic richness with emotional clarity. Nature is used symbolically—peaceful forests to reflect purity, turbulent seas to mirror crisis. The play is structured around Karuna Rasa (pathos), but it avoids melodrama by grounding sorrow in universal human experiences: a mother’s grief, a young prince’s fear, a wife’s impending loss. Harsha also integrates religious syncretism, merging Buddhist compassion with Hindu mythological motifs, creating a drama that feels ethically universal rather than doctrinally narrow.

Nagananda stands apart because it argues for a kind of heroism rarely celebrated in classical literature: the heroism of compassion. It presents a world in which violence is not conquered by greater violence but by moral clarity. Its protagonist wins not through force but through willingness to bear suffering for others. Harsha’s drama challenges audiences to reconsider their assumptions about power, duty, and greatness. For this reason, Nagananda remains one of the most spiritually resonant and ethically profound works in Sanskrit theatre.

Abha Bhardwaj Sharma is a Professor of English Literature with over 25 years of teaching experience. She is the founder of Miracle English Language and Literature Institute and the author of more than 50 books on literature, language, and self-development. Through The Literary Scholar, she shares insightful, witty, and deeply reflective explorations of world literature.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance