3. Modernism : After the Guns Fell Silent — Literature Between Wars

A world trying to forget. A literature that refused to.

From The Professor's Desk

The war was over. But the wound was not.

Modernist literature between World Wars

The year was 1919. Europe was exhausted—physically, spiritually, artistically. The battlefield had fallen quiet, but the silence was not peace. It was the hollow quiet of disillusionment, of graves filled too early and ideals buried with them. The certainty that had once upheld Victorian morality, imperial confidence, and rational progress had bled into the mud of Flanders.

Writers who emerged after the Armistice weren’t singing songs of victory. They were navigating the emotional debris of a century betrayed. They had witnessed the death of order—and were now struggling to make sense of a world adrift from its moorings.

This was the age between wars, between faiths, between identities. It was a liminal zone where time was fractured, memory became suspect, and consciousness was no longer linear but layered, repetitive, anxious. Art stopped reflecting the world and began breaking it into fragments—to examine, to expose, and sometimes, to escape.

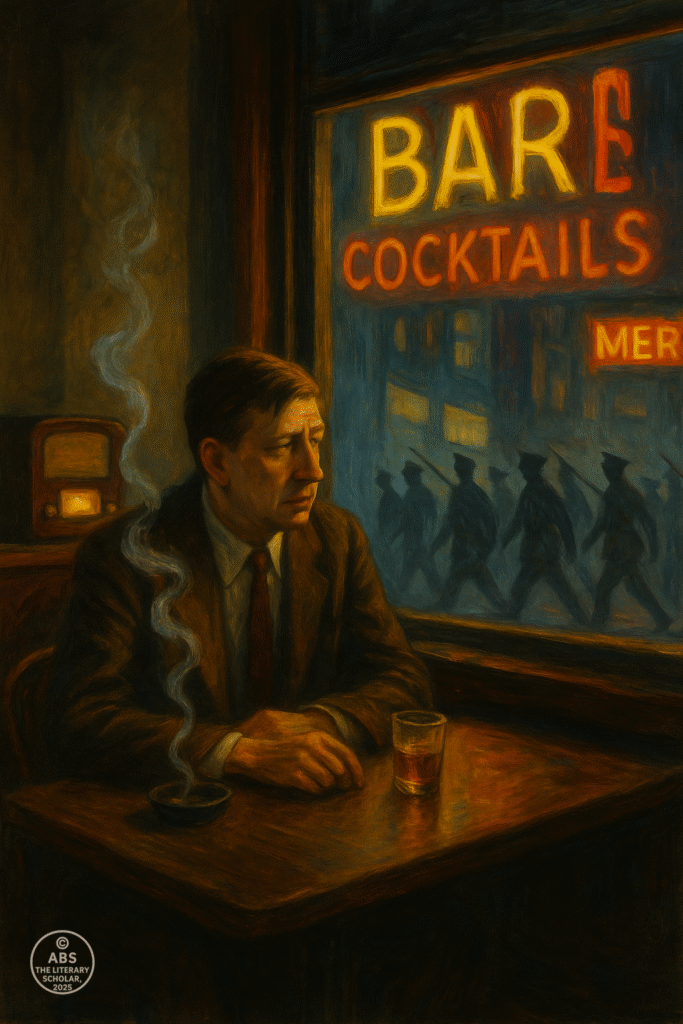

It was also the age of cities: London, Paris, Berlin, New York. Urban life became not a symbol of progress, but of anonymity, alienation, and over-stimulation. The rural idylls of Hardy were gone. In their place: neon signs, jazz clubs, smoky cafés, and the existential loneliness of a crowd.

In this volatile cultural moment, literature underwent its most radical transformation since the Renaissance. The novel no longer obeyed plot. Poetry no longer rhymed. The self was no longer whole.

Modernism had arrived. And it didn’t knock. It broke the door.

This third scroll of the journey through literature explores the interwar years: a period of psychological interiority, formal innovation, and philosophical crisis. From the fragmented voices of Eliot and Joyce to the shimmering inner worlds of Virginia Woolf, from the spiritual turbulence of Yeats to the existential precision of Auden, the literature of this age did not pretend to offer comfort. It offered depth, complexity, and an unflinching mirror to a civilization trying to redefine itself.

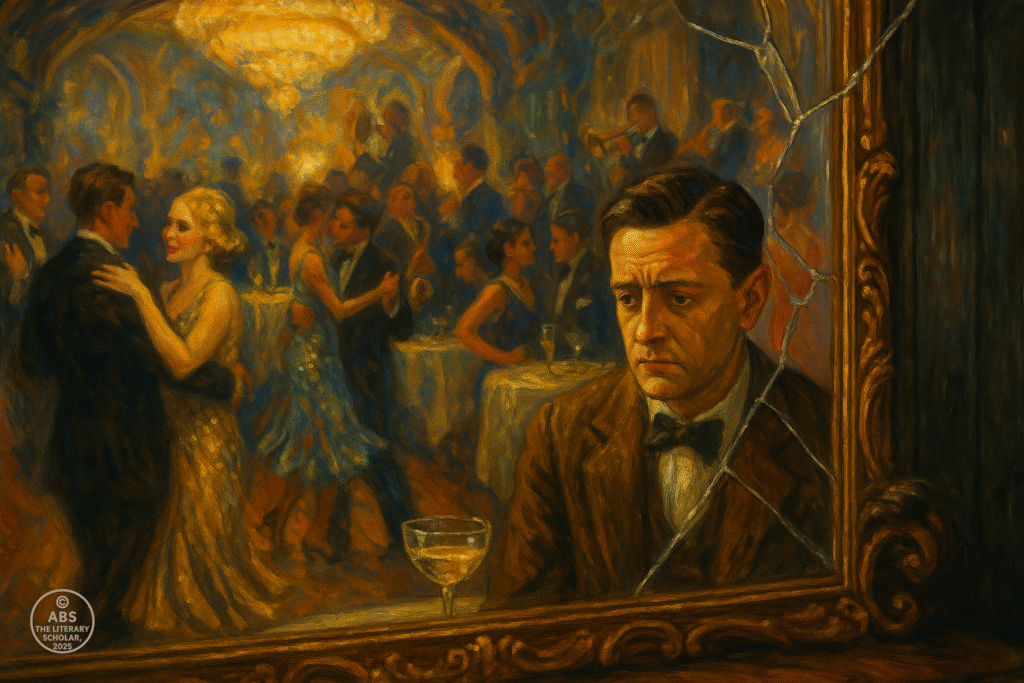

The Roaring Twenties and the Cracked Mirror

The war was over, but the chaos was not.

The 1920s arrived not with solemn reflection but with jazz, gin, and jolting laughter—the laughter of those who had seen too much and now lived as though tomorrow had no promise. Across Europe and America, the cultural mood split down two strange tracks: one of glittering modernity, the other of existential dread.

The term “The Roaring Twenties” captured the visible surface: flappers, cocktails, speakeasies, and the Charleston. The real story, though, was the attempt to outrun grief through glitter, and to bury memory beneath motion. The dance was a deflection. The drink was a denial. The art, however, told the truth.

In literature, this was the decade of disorientation. Writers no longer trusted the world to make sense, so they stopped pretending their texts did either. Linear plots collapsed. Chronology was distorted. Characters disintegrated. The novel, once a gentleman’s game of manners and morals, became a laboratory of inner voices, of consciousness breaking its own rules.

James Joyce shattered the English sentence in Ulysses (1922), turning the streets of Dublin into a mythic, mind-bending maze of thoughts, fragments, and puns. Every hour in Leopold Bloom’s day was a battleground of language, where Homeric epic met Dublin street slang. Joyce did not write a story. He recomposed reality.

Virginia Woolf, in the same year, gave us Jacob’s Room, and then Mrs. Dalloway (1925), a novel in which a single day stretches infinitely inward. Her narrative flowed not through actions but through perceptions. One moment, Clarissa is buying flowers. The next, she is reliving twenty years of sorrow, joy, and unrealized love. Woolf’s technique, now known as stream of consciousness, dissolved time itself: the past invaded the present, and memory was a form of truth deeper than fact.

Meanwhile, T.S. Eliot, haunted by the trauma of the war and personal collapse, published The Waste Land (1922)—a poem that sounded like civilization itself trying to speak through ruins. It offered no comfort, no closure, only fragments shored against collapse. It was modernity’s funeral hymn. In the echo of “April is the cruellest month,” we hear the disillusioned sigh of a generation whose springs no longer promised renewal.

Behind these masterpieces was a broken belief in narrative coherence. Language was no longer trusted. Identity was no longer fixed. Society, once anchored in shared ideals, was now adrift in a sea of selves.

And so the 1920s, though roaring, were not joyous. They were rebellious, experimental, and haunted. The laughter of the decade was nervous. The beauty, jagged. The literature, revolutionary.

The Bloomsbury Circle and the Inner Cosmos

While the rest of Europe stumbled through smoke and disillusionment, a peculiar constellation of minds gathered in London’s Gordon Square and Sussex retreats. They were called the Bloomsbury Group, but their conversations were not polite tea talk. These were thinkers and writers who believed—radically, then—that art, ideas, and emotions mattered more than money or institutions.

Led by Virginia Woolf, her husband Leonard Woolf, economist John Maynard Keynes, biographer Lytton Strachey, artist Vanessa Bell, and novelist E.M. Forster, among others, the Bloomsbury set rejected Victorianism with the elegant savagery of a generation that had seen it lead to war. They embraced emotional truth over convention, introspection over spectacle, and aesthetic honesty over moral pomp.

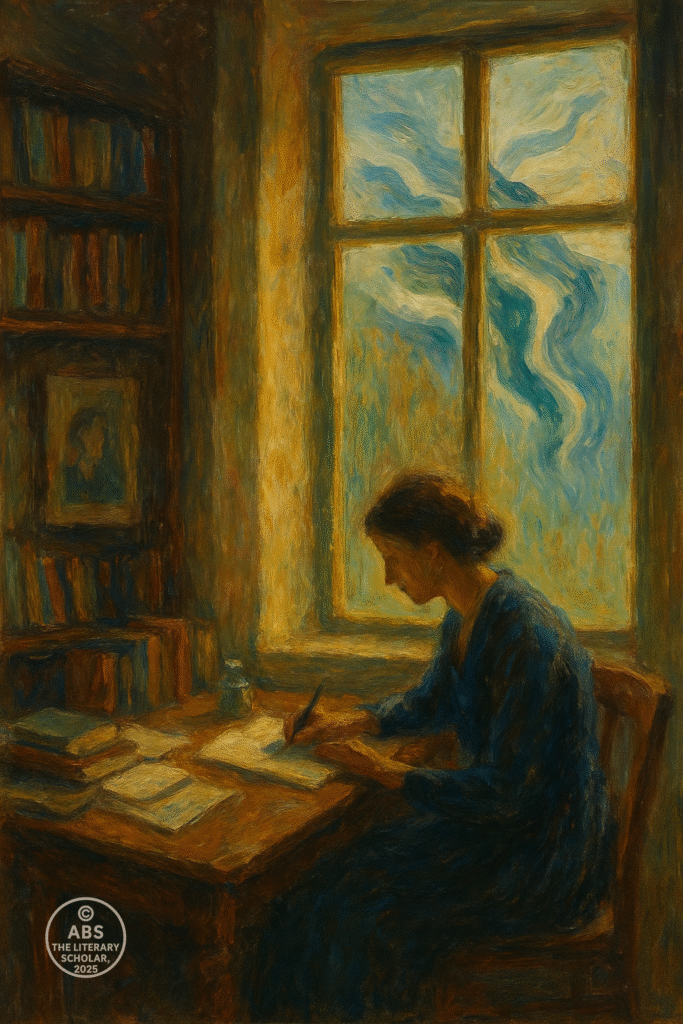

For Woolf, literature was not just a mirror held up to life—it was the soul trying to speak through sensation. In To the Lighthouse (1927), she paints not a family vacation, but a fractured landscape of unspoken grief, mother-worship, and temporal decay. What happens in the plot is minimal; what happens in the spaces between the lines is monumental. Time passes in silence. Love mutates. Memory reshapes reality.

Woolf’s essays, especially A Room of One’s Own (1929), made a quieter but equally seismic impact. With scholarly wit and sharp restraint, she declared that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” This was not only an appeal for artistic independence—it was a challenge to the patriarchy’s monopoly on narrative.

E.M. Forster, more traditional in plot but no less radical in spirit, asked uncomfortable questions about connection and empire. A Passage to India (1924) is not a travelogue but a metaphysical riddle: Can friendship exist between colonizer and colonized? Can truth survive the weight of race and politics? The Marabar Caves are not just geological oddities. They echo back the hollowness of human intention.

Meanwhile, Lytton Strachey skewered Victorian morality with surgical satire in Eminent Victorians (1918), revealing that heroes of the past were often pompous, repressed, or ridiculous beneath their polished reputations. This irreverence—intellectual and literary—became Bloomsbury’s quiet revolution. They questioned the past not with fire, but with irony.

More than a group, Bloomsbury was a mood, a philosophy, a refusal to perform Victorian life anymore. They replaced grandeur with nuance, and spectacle with thought. In their hands, literature became not a performance of character, but an excavation of consciousness.

As the world spun faster and louder, the Bloomsbury writers retreated inward—to thoughts, sensations, and fragile identities—and in doing so, gave the inner life a literary architecture that endures.

The American Lost Generation — Glamour, Disillusionment, and Exile

While Europe was piecing itself back together with trembling hands, a wave of young American writers was crossing the Atlantic—not in search of war, but of meaning. The term “Lost Generation,” coined by Gertrude Stein and immortalized by Ernest Hemingway, did not mean they had lost the war. It meant they had lost their illusions.

They had grown up believing in the American Dream—only to watch the trenches of Europe turn it to mud. They were, in Hemingway’s words, “strong in will but hollowed in spirit.” And in Parisian cafés and Spanish bullrings, they began to write not about hope, but about the cost of believing in it.

Ernest Hemingway, a former ambulance driver and war correspondent, changed prose forever. His sentences bled restraint—short, sharp, stripped of sentiment. The Sun Also Rises (1926) was not about the excitement of Europe, but its weariness. Its expatriate characters drift through Spain and France, drinking, dancing, and trying—failing—to feel something real again. Jake Barnes, wounded in body and soul, became the prototype of the emotionally muted modern man.

In A Farewell to Arms (1929), Hemingway revisits war only to reject every romantic notion of heroism. Catherine dies, the baby dies, and there is no noble closure. “The world breaks everyone,” he wrote, “and afterward many are strong at the broken places.” But some, he implies, are not.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, meanwhile, turned his gaze to the shimmering façade of America itself. The Great Gatsby (1925) is not a love story—it is a funeral for the American Dream. Jay Gatsby, who believes he can buy back the past, is destroyed not by love, but by the cruelty of wealth. East Egg wins. The green light fades. And “we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Fitzgerald’s prose was lyrical, but his world was ruthless. Behind the champagne flutes and jazz music was a moral hangover that modernity could not shake. In Tender Is the Night (1934), even the beautiful are broken—especially the beautiful. His own life mirrored his characters: glittering beginnings, followed by decline and despair.

Gertrude Stein, in contrast, did not mourn the past. She shattered language itself. Her experimental works, like Three Lives (1909) and Tender Buttons (1914), abandoned traditional narrative and treated words as objects to be turned, twisted, examined under light. She was not just writing literature—she was inventing a new logic for it. To many, she was incomprehensible. To the future, she was revolutionary.

John Dos Passos gave us Manhattan Transfer and The U.S.A. Trilogy, merging stream-of-consciousness, newspaper headlines, and personal testimonies to capture the industrial rhythm and political anxiety of the American metropolis. His work was montage, not melody—restless, fragmented, deeply modern.

Collectively, the Lost Generation chronicled a world drunk on progress but hungover on meaning. Their characters drift, love recklessly, betray, search for transcendence, and find only disillusionment. They are romantics in exile, stranded between two wars, writing in a language of graceful despair.

But even in their ruin, they gifted literature something invaluable: a new honesty. They stopped pretending that life made sense. And in doing so, they helped us recognize the beauty in its brokenness.

Poetry in Fragments — The Rise of the Modernist Lyric

If the prose of the Lost Generation murmured disillusionment, the poetry of the 1920s screamed in silence. The old poetic forms—rhymed quatrains, sonnets of romantic yearning—could not capture a world where God had gone quiet and meaning lay buried beneath barbed wire. Into this vacuum stepped the Modernist lyricists, armed with shards of classical allusion, broken syntax, and a desperate hunger for form in a formless age.

No figure stands taller—or more anxiously hunched—than T.S. Eliot. His 1922 masterpiece, The Waste Land, was not merely a poem; it was a psychological excavation. Beginning with “April is the cruellest month,” Eliot announced the death of spring itself, turning resurrection into mockery. The poem drifts through languages, myths, broken cities, and broken people, guided by fragments that refuse to heal.

It is a poem where “a heap of broken images” becomes both diagnosis and structure. Eliot’s world has no central narrative—only voices, echoes, quotations from Dante, Shakespeare, the Upanishads. Tiresias, the blind prophet who has lived as both man and woman, becomes the ultimate modern narrator: seeing everything and believing nothing.

And yet, amidst the despair, Eliot does not forsake order. He searches for meaning in rhythm, religion, and ritual. The closing Sanskrit triad—Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.—offers not answers, but spiritual gestures. Give. Sympathize. Control. It is not salvation, but it is something.

Meanwhile, Ezra Pound, once Eliot’s editor and forever his provocateur, was constructing his own epic—the Cantos. If The Waste Land was a fragmented mirror, the Cantos were a kaleidoscope smashed and reassembled into mosaic prophecy. Drawing from Confucius, Greek tragedy, Renaissance finance, and troubadour verse, Pound’s work is brilliant, baffling, and sometimes dangerous. His politics darkened; his anti-Semitism cannot be excused. And yet, his poetic ambition remains unmatched: he wanted to remake civilization through meter.

Then came H.D. (Hilda Doolittle)—the high priestess of Imagism, often overlooked because she was a woman in a man’s century. Her verse, delicate yet precise, redefined lyricism. “Oread,” her most famous poem, is six lines long and contains a sea and a forest fighting in metaphor. Her poetry is compressed mythology—the ancient world, seen through modern anguish.

Her later work, especially Trilogy, written during the Blitz, is a spiritual resistance to chaos. “We are each a part of the great fracture,” she seems to whisper, “but even cracks let in the light.”

Modernist poetry, then, was not a rejection of beauty—it was a redefinition of it. Beauty was no longer in wholeness, but in sharp clarity, in haunting echo, in linguistic fracture. It was in the rhythm of a city bombed to silence. In the voice that spoke not from Olympus, but from an underground bunker.

These poets didn’t just write poems. They changed how poetry breathed.

Women in Words — Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West, and the Gendered Mind

As the cannons went silent and the trenches emptied, another revolution began quietly — inside rooms, inside minds, inside women. If the Great War shattered the masculine myth of empire and honour, it also cracked the Victorian mould of womanhood. Out of that fracture rose one of the most luminous, elusive voices of the 20th century: Virginia Woolf.

Woolf did not storm the gates of literature. She slipped through them like light under a door. Her prose was not loud, but it was radical. In novels like Mrs. Dalloway (1925) and To the Lighthouse (1927), she dismantled linear time, disrupted narrative authority, and centered the elusive inner life — particularly that of women. Her writing was a mirror held not to faces, but to thoughts.

Take Clarissa Dalloway, walking through a June day in postwar London, buying flowers, planning a party — and simultaneously sifting through decades of memory, emotion, and regret. Her consciousness is not tidy; it is a swirl of past and present, love and loss, domesticity and existential dread. The ticking clock is no longer a plot device — it is a metaphysical presence.

Woolf’s prose flows like thought, untethered from chapters and chores, moving instead by rhythm and association. “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself”—a line so simple, and yet beneath it lies an entire world of gendered autonomy and suppressed agency. Clarissa cannot change the world, but she will curate her own corner of it — and in that act, claim a kind of freedom.

Woolf’s literary ally and inspiration was Vita Sackville-West, poet, novelist, and her great love. Vita’s flamboyance and androgynous grace became the model for Orlando, Woolf’s genre-defying biographical novel in which a nobleman becomes a woman across four centuries. The novel isn’t just a gender-bending fable — it is an act of liberation: from history, from fixed identity, from patriarchy’s stiff collar.

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction,” Woolf famously declared in her 1929 extended essay A Room of One’s Own. This was no mere metaphor. It was a manifesto for intellectual space, for the economic and emotional independence required to create.

The essay dismantled centuries of exclusion — of Shakespeare’s hypothetical sister, as gifted but silenced by gender. Woolf wrote what generations of women had only felt: the ache of unrealized genius, the quiet rage of having no name on the library shelf.

And yet Woolf never thumped the pulpit. Her feminism was nuanced, even poetic. She didn’t ask for vengeance, only vision. Not just equality, but interiority. In a world drunk on masculine certainty, she offered the intoxicating ambiguity of emotion, the beauty of fluid perception.

She didn’t walk alone. Writers like Dorothy Richardson, Rebecca West, Katherine Mansfield, and Djuna Barnes were also shifting the literary centre — bringing intimacy, trauma, sensuality, and psychological depth into prose. These women wrote not to prove themselves, but to make space for a self to exist at all.

In a way, Woolf gave the 20th century its most important literary instrument: the inward gaze. She taught prose how to breathe like a woman — quietly, deeply, but never submissively.

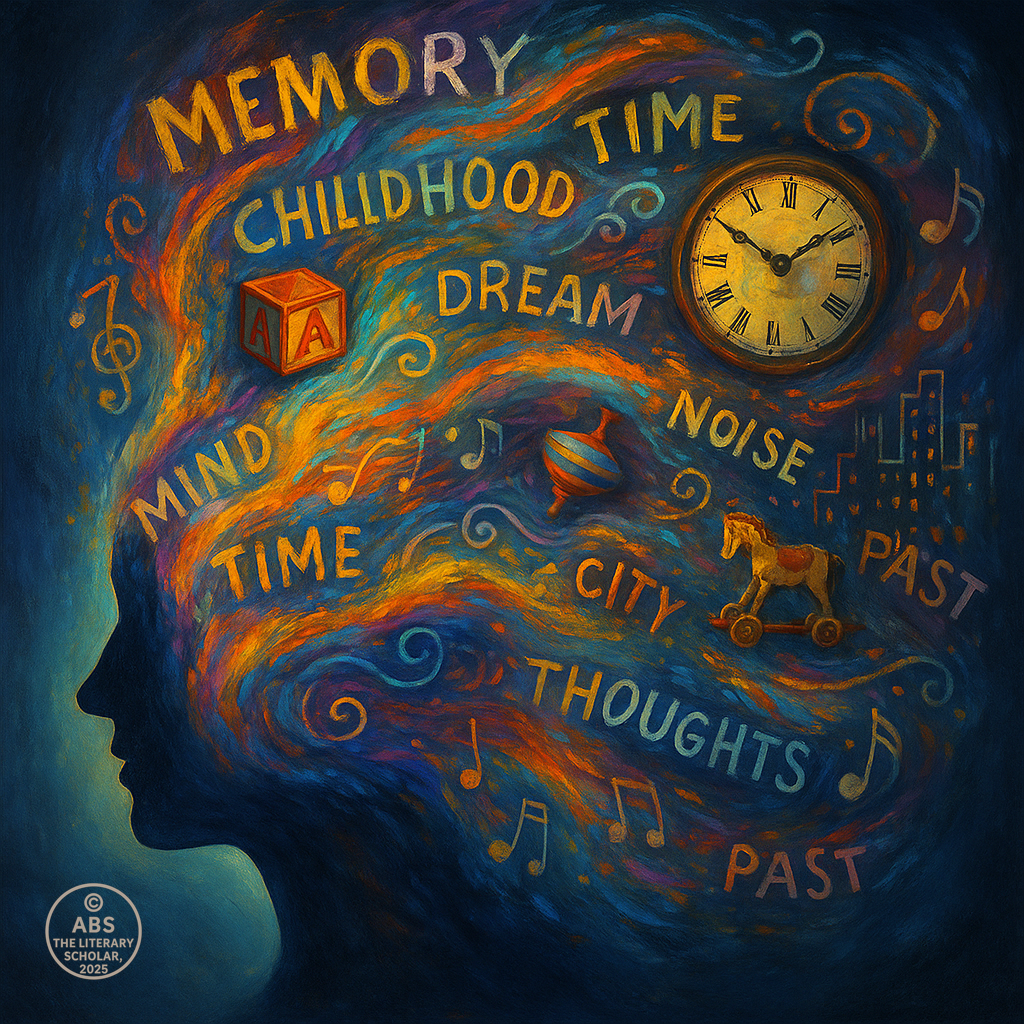

The Mind Unleashed — Freud, Jung, and the Dreaming Self in Literature

As the 20th century staggered into modernity, the battlefield shifted from mud and bullets to memory and mind. The most profound revolutions were now psychological. No longer content with surface reality, literature turned inward — toward the unconscious, the fragmented self, the buried trauma. And standing at the crossroads of this inward turn were Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, whose ideas poured like ink into modernist writing.

Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams (1900) wasn’t just a book — it was a seismic tremor beneath the foundations of Western thought. He argued that human beings were not governed by rationality but by impulses, repressions, desires cloaked in dreams. The conscious mind was a polite host, he said — but the unconscious was a wild guest banging on the cellar door.

Writers paid attention.

In Freud’s model of the psyche — id, ego, superego — authors found new metaphors for inner conflict. The neat moral categories of Victorian fiction seemed embarrassingly shallow. Characters were no longer just good or bad. They were complicated, driven by shadows they didn’t fully understand.

Take Franz Kafka, the Prague-born prophet of psychological absurdity. In The Metamorphosis (1915), a man wakes up transformed into a giant insect — and the horror is not in the grotesque body, but in the emotional numbness of his family. This wasn’t just surrealism — it was a metaphor for alienation, anxiety, and the modern ego crushed beneath expectation.

Kafka’s bureaucratic nightmares (The Trial, The Castle) read like case studies in repression. His protagonists wander through mazes of accusation and futility — dream-logic turned bureaucratic, where guilt precedes crime and identity is erased by paper and procedure. If Freud revealed the mind’s chaos, Kafka built a world that resembled it.

Meanwhile, Carl Jung added spiritual depth to psychology. He spoke of archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the individuation process. He viewed dreams not as symptoms, but as symbols — coded messages from the soul, echoing across cultures and epochs. Literature found in Jung a license to be mythic again.

T.S. Eliot, for instance, didn’t just write The Waste Land as a post-war lament — he composed a Jungian collage of mythical fragments: Tiresias, the Fisher King, the Upanishads. The poem speaks not just to one man’s crisis, but to the wounded psyche of civilization. “These fragments I have shored against my ruins”—a line that feels like therapy through myth.

Even Virginia Woolf’s stream of consciousness bears Freudian fingerprints. Her characters — Clarissa, Septimus, Mrs. Ramsay — don’t just think, they feel in waves. The past returns in flashes, repression dances with memory, and time flows as sensation. Woolf did not “apply Freud,” but rather absorbed the climate he helped create.

James Joyce, too, dove deep into the subconscious. Ulysses (1922) unfolds across a single day in Dublin, yet inside Leopold Bloom’s mind are infantile memories, sexual desires, Oedipal guilt, all flickering in a constant interior monologue. Freud himself is not mentioned — but he is haunting every page.

The theatre, too, joined this revolution. Expressionist drama — from Strindberg to Eugene O’Neill — turned stages into dreamscapes. Characters spoke to their shadows, hallucinatory figures walked through rooms, and lighting mirrored neurosis. Realism was no longer enough. The psyche needed its own stage design.

By the 1930s, literature had internalized psychology so deeply that even style changed. Sentences grew more associative, dialogue interrupted by memory, imagery turned symbolic. Characters no longer “acted” — they unraveled.

And yet, not all embraced Freud with fanfare. Some writers — notably D.H. Lawrence — accused Freud of shrinking sexuality into neurosis. Lawrence demanded a deeper, more visceral and life-affirming psychology, rooted in primal vitality, not analysis.

Still, Freud and Jung had thrown open the door. Literature was now a confession, a dream journal, a labyrinth of unspoken motivations. The mind was no longer a mystery to be solved — it was a novel to be written.

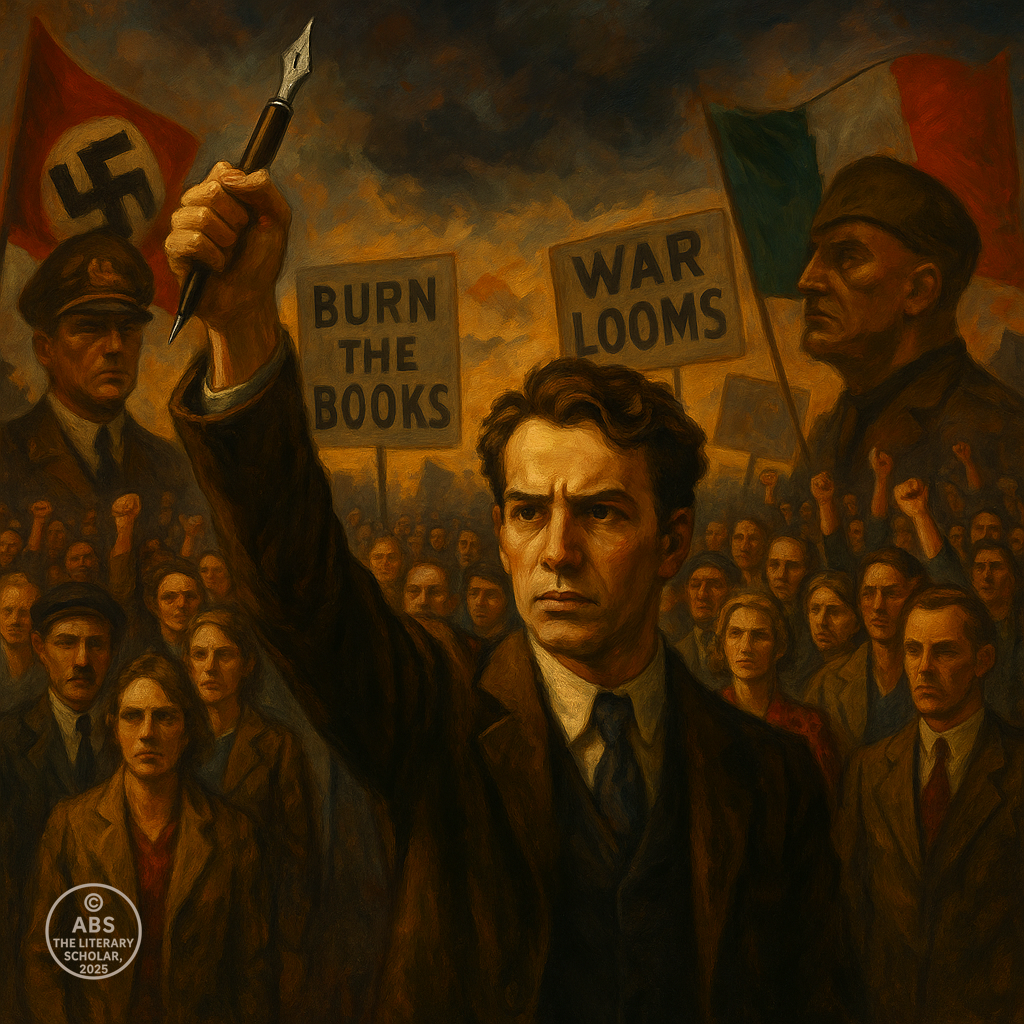

Dictators, Dystopias, and the Literature of Warning

If the First World War wounded the body of Europe, the 1930s marked the onset of ideological fevers that burned through its soul. From Berlin to Moscow, Rome to Madrid, the post-war hope curdled into totalitarian ambition. Literature, always an anxious thermometer of human history, began to tremble with urgency.

The age saw the rise of demagogues and doctrines—Stalinism in Russia, Fascism in Italy, Nazism in Germany, and authoritarianism brewing across Europe. The result? A culture of fear, censorship, and control. But out of this darkness emerged a different kind of literature: the literature of warning.

Writers, exiled or silenced, responded with words that cut deeper than any sword.

George Orwell: The Prophet Who Understood Propaganda

Though his masterpieces would come later, Orwell’s political clarity was already sharpening in the 1930s. A veteran of the Spanish Civil War, he saw firsthand the twisting of truth into ideology. His 1938 memoir Homage to Catalonia isn’t just reportage — it’s a chronicle of betrayal, where leftist factions tear each other apart even while fighting fascism. Orwell’s disillusionment with communism began here.

Orwell’s experience shaped his later dystopias, but even in the 1930s, he was sketching the outlines of what would become Big Brother, Newspeak, and the Ministry of Truth. In Orwell’s universe, language is weaponized, truth is bent until it breaks, and the very act of remembering becomes political resistance.

Aldous Huxley: Pleasure as Control in Brave New World (1932)

While Orwell warned of fear-based tyranny, Huxley offered an eerily smiling alternative: tyranny through pleasure. In Brave New World, people are not oppressed by violence but by soma pills, synthetic entertainment, and engineered complacency. It is a world where freedom is traded for comfort, and thought is drowned in noise.

The novel’s chilling brilliance lies in how its satire now feels prophetic: test-tube babies, genetic engineering, consumerist addiction, and a society that prefers happiness over truth. Huxley’s question echoes today: “What happens when people love their servitude?”

Bertolt Brecht: Theatre as a Political Act

While Orwell and Huxley wrote novels, Bertolt Brecht revolutionized the stage. Exiled from Nazi Germany, Brecht believed theatre should not comfort—it should confront. His Epic Theatre broke the illusion of realism, forcing audiences to think rather than feel.

In plays like Mother Courage and Her Children, Brecht dissected war profiteering, moral ambiguity, and the personal cost of ideology. He employed alienation effects—songs, direct address, abrupt scene changes—not to entertain, but to jar the viewer into social awareness.

Thomas Mann and the Decline of the European Intellect

Meanwhile, writers like Thomas Mann, exiled from Hitler’s Germany, mourned not just politics but the collapse of humanism itself. In The Magic Mountain and Death in Venice, Mann explored decadence, time, disease, and the decline of the intellect in a society that once prided itself on culture. Nazism, to Mann, was not an accident — it was the endgame of European arrogance.

Censorship, Exile, and Silencing

Not all literature could be written freely. In Nazi Germany, books were burned. Jewish, socialist, or modernist authors were outlawed. Brecht fled. Thomas Mann fled. Kafka had already died — but his books were banned. In Stalinist Russia, writers were either co-opted into Socialist Realism or disappeared into gulags.

The writer in this era was not just an artist — they were a survivor, a resistor, a fugitive. Their pen was a lantern in the storm, not just describing the dark but defying it.

The Rise of Allegory, Symbolism, and Surrealism

How does one write truth in a time of lies?

Many authors turned to allegory and metaphor. The surreal, the symbolic, the dystopian—these became tools to slip past censors, to speak what could not be spoken. Whether in Brecht’s songs, Huxley’s factories, or Orwell’s ministries, literature became a coded protest, a whispered rebellion in the ear of time.

The totalitarian era taught writers a bitter truth: freedom of expression is not a luxury — it is a warning bell. When literature is forced underground, civilization itself is already in peril.

Women Between Wars — Voices from the Shadows

Between the twin catastrophes of the World Wars, something quieter, but no less revolutionary, was unfolding — the emergence of a woman’s voice, long muffled by Victorian decorum and patriarchal history. If the men had fought on battlefields, women had fought at home — in factories, in fields, and in the inner trenches of identity and thought. By the 1920s and ’30s, they were not just supporting characters in literature — they were writing their own scripts.

Virginia Woolf: The Mind as a Room, the World as a Wave

In the vanguard of this awakening stood Virginia Woolf, whose novels were less about plot than the flickering light of thought itself. Her works Mrs Dalloway (1925) and To the Lighthouse (1927) are not linear narratives but streams of consciousness — fluid, unpunctuated, inward.

She peeled away external action to explore what happened inside the mind: Clarissa Dalloway’s quiet rebellion through social ritual, Mrs Ramsay’s meditations on love and time, Septimus Smith’s war-haunted collapse. Woolf gave literature a female interiority, a space for reflection that had long been denied.

In A Room of One’s Own (1929), she stated it plainly: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” This was more than advice — it was a literary manifesto. She challenged the canon, resurrected forgotten female authors, and warned that the silence of women was not natural — it was enforced.

Katherine Mansfield and the Art of the Moment

Katherine Mansfield and the Art of the Moment

New Zealand-born Katherine Mansfield, whose short life produced radiant stories, redefined how short fiction could breathe. In tales like The Garden Party and Bliss, Mansfield didn’t offer clear morals or resolutions. Instead, she captured epiphanies, disappointments, and the tremors beneath polite smiles.

Her female characters are often trapped — by gender, marriage, class — yet momentarily radiant in their confusion. Bliss and betrayal arrive in the same sentence. Mansfield’s fiction is precise, elliptical, and devastatingly real, and it showed how a woman’s truth could be told without apology.

Edith Wharton and the Gilded Cages

Across the Atlantic, Edith Wharton was peeling back the velvet curtains of upper-class America. Her novels The Age of Innocence (1920) and The House of Mirth (1905, still resonant) dissect the world of drawing rooms and social manners — only to reveal the unspoken cost of conformity. Her heroines, like Lily Bart and Ellen Olenska, are poised at the edge of independence, punished for being too modern, too bold.

Wharton saw the double standard clearly: society forgives male transgression but brands female desire as dangerous. Her fiction anticipated second-wave feminism decades ahead.

Jean Rhys and the Ghost of the Colonized Woman

Then came Jean Rhys, the haunting voice behind Good Morning, Midnight (1939) and later Wide Sargasso Sea (1966, her great reclamation of Bertha from Jane Eyre). Rhys gave voice to the colonial, Creole, emotionally unraveling woman — unmoored, unnamed, uncared for.

Her characters don’t shout — they drift. They are lost in European cities, alcoholic, heartbroken, bleeding into the cracks of modern life. Yet in that silence is something shattering: a refusal to perform. Rhys’s women are not symbols of virtue or rebellion — they are raw, real, and impossible to dismiss.

Themes That Echoed Like Subtext

These writers didn’t need battlefields. Their war was subtler: against invisibility, against erasure, against being confined to footnotes. Their weapons were metaphor, irony, mood, and memory.

What bound them was the sense that:

The world no longer belonged to inherited systems — of family, class, and gender.

Women were no longer content to be muses — they wanted to be the author, too.

The sentence itself had to change — to accommodate breath, pause, hesitation, doubt

Aesthetics of Isolation — Art Between the Wars

If the post-war years rewrote the content of literature, they also redrew its aesthetic boundaries. Writers were not only questioning what to say — but how to say it. The old forms, rigid and orderly, could no longer contain a world that had fractured at its core. Between the Great War and the one still looming on the horizon, art became unmoored. It floated in silence, shuddered in abstraction, and searched for meaning in the gaps.

This was the era when modernism truly crystallized — not as a single style, but as a shared rebellion against comfort, closure, and clarity.

Form Fragmented, Meaning Fractured

Modernist writers did not trust the polished novel or the neat rhyme. They distrusted narration that knew too much, and characters who grew too easily. Instead, they gave us interior monologues, broken syntax, multiple narrators, temporal jumps, and elliptical closures. The reader was no longer an observer but a participant in decoding.

T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922) wasn’t a poem you read once — it was a puzzle you lived with. His footnotes mocked traditional scholarship while pretending to support it. His juxtaposition of ancient myth and modern detritus created a mosaic of cultural anxiety — a haunted postwar civilization speaking in the tongues of lost gods and broken radios.

James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) was another watershed: a novel of one day, but a cosmos of all time, where grocery lists jostled with Homeric epics. The form didn’t just reflect life — it became life’s chaos, unruly, intimate, and unfiltered.

The Aesthetic of Difficulty

To read a modernist text was to abandon the comforts of Victorian omniscience. There were no handrails, no lamps to guide the reader — only shadow and pattern. This wasn’t elitism; it was honesty. The modernists were saying: this is what it feels like to live now. Fragmented. Overstimulated. Alone. Unsure whether meaning is lost — or simply out of reach.

Ezra Pound’s command — “Make it new” — was not about novelty. It was a demand for relevance, resilience, and reinvention.

Silence and Symbolism

The era’s aesthetic of isolation was not just verbal — it was also emotional. Characters in modernist novels rarely find closure. Their relationships are suspended, their dialogues fractured. Even their epiphanies are ambiguous.

In Woolf’s The Waves, the characters speak in poetic soliloquies, but never quite to each other.

In Kafka’s The Trial, meaning is eternally deferred — a bureaucratic nightmare becomes an existential parable.

In Beckett’s embryonic work, even action begins to dissolve — waiting becomes the drama.

Visual Art and Parallel Echoes

This aesthetic rupture was not limited to literature.

In painting, Cubism (Picasso, Braque) fragmented the visible world into geometric shards.

Surrealism (Dalí, Magritte) turned the subconscious into a canvas.

Expressionism (Kirchner, Munch) screamed the inner world onto the outer frame.

Even architecture, via Bauhaus, declared: form must follow function — not ornament.

This was an aesthetic of tension, absence, and experimentation — a world rebuilding its forms while still mourning its collapse.

Technology and the Mechanized Self

At the same time, modernist art began to reflect the new machine age. Typewriters, telephones, radio, cinema — these changed not only communication but cognition. Humans were beginning to think in jump cuts, montage, and mechanical rhythms. Poets like Auden, writers like Dos Passos and Eliot, reflected this industrial tempo in syntax and imagery.

The world was no longer pastoral — it was urban, electric, humming with speed and nerves.

Alienation Became a Style

This period codified a truth that remains: literature is not just what is said — it is also what is unsaid. Modernist art left things out deliberately. It honored silence as a medium of meaning.

The characters don’t speak directly. The symbols are not explained. The plots don’t conclude.

Because in a world after trenches and telegrams, certainty was a lie. What remained was gesture, tone, and absence.

And So…

As the 1930s drew to a close, the literary world stood at a strange threshold. It had invented new languages for grief, identity, and fragmentation. It had redefined the novel, the poem, and the essay.

But another storm was gathering — political, violent, global. The age of introspective innovation was about to be interrupted again by boots, bombs, and borders.

From Woolf’s window to Auden’s Manhattan, from Joyce’s Dublin labyrinth to Huxley’s synthetic dystopia, from the murmured narratives of exile to the shouted warnings of resistance — literature became both seismograph and siren.

It did not always make sense.

But neither did the century.

This was the bridge — the one walked by writers, not warriors — from the ruins of one war to the brink of another. They did not escape history. But they made it endurable. They turned chaos into craft.

And when the storm returned in 1939, it found them not unprepared — but deepened, sharpened, and waiting at their desks.

Signed,

The Professor’s Desk

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance