MODERNISM: Literature in a Broken World

(Modern Literature from 1901 to ~1955 — shaped by War, Science, Psychology, and Disillusionment)

From The Professor's Desk

“A New Century Dawns — But With Strange Clouds”

“The year was 1901. Victoria, the great empress, lay dead. The world was tilting into the modern age. Electric light had begun to outshine the gas lamp. The horse-drawn carriage was giving way to the motorcar. And in the literary salons of London, Paris, and Dublin, something restless was stirring.”

The year was 1901. Victoria, the great empress, lay dead, and with her passed the long 19th century’s illusion of order. The world was tilting—gently, then violently—into the modern age. Electric light had begun to outshine the gas lamp, just as motorcars crept up beside the aging dignity of horse-drawn carriages. Across the literary salons of London, Paris, and Dublin, something restless, something unsatisfied, had begun to stir. A century was ending, but more than a date had changed. The air itself seemed charged with discontent, therefore modern literature in a broken world took birth.

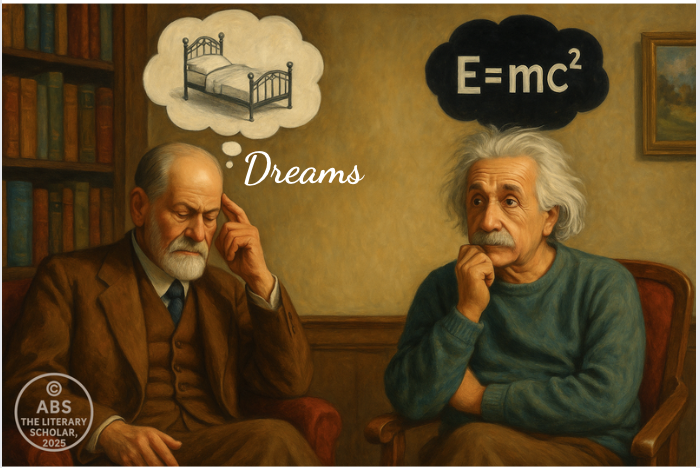

On the surface, the new century gleamed with the seductive promise of progress, peace, and plenty. The British Empire stood at its zenith, draped in flags and confidence. Science, now unbound by metaphysics, whispered of hidden energies and invisible waves. Einstein’s quiet revolution in 1905 would soon dismantle Newton’s cosmos, while X-rays, wireless telegraphy, and flying machines promised to rewire time and space itself. And in a quiet Viennese room, Freud cracked open the mind to reveal a darker, more primal self—haunted by dreams, split by repression, ruled by instincts that defied reason.

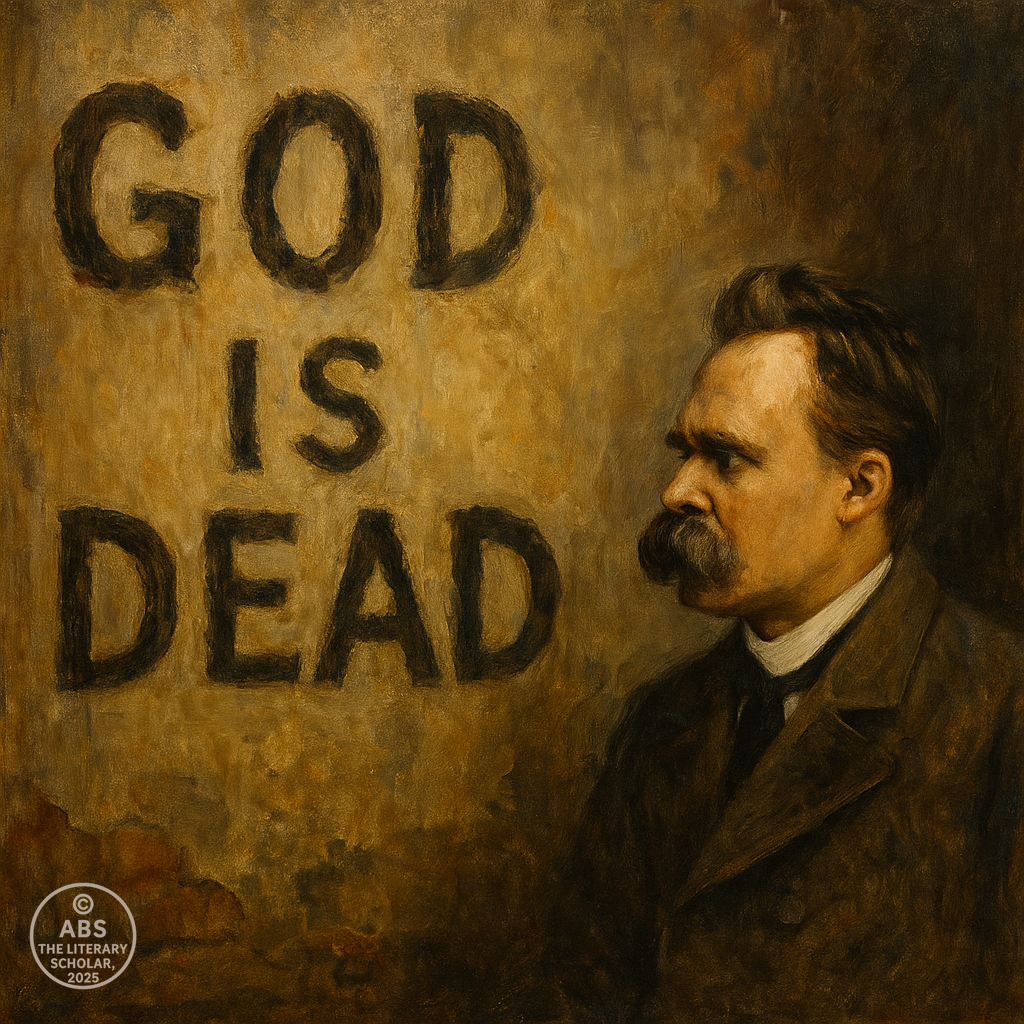

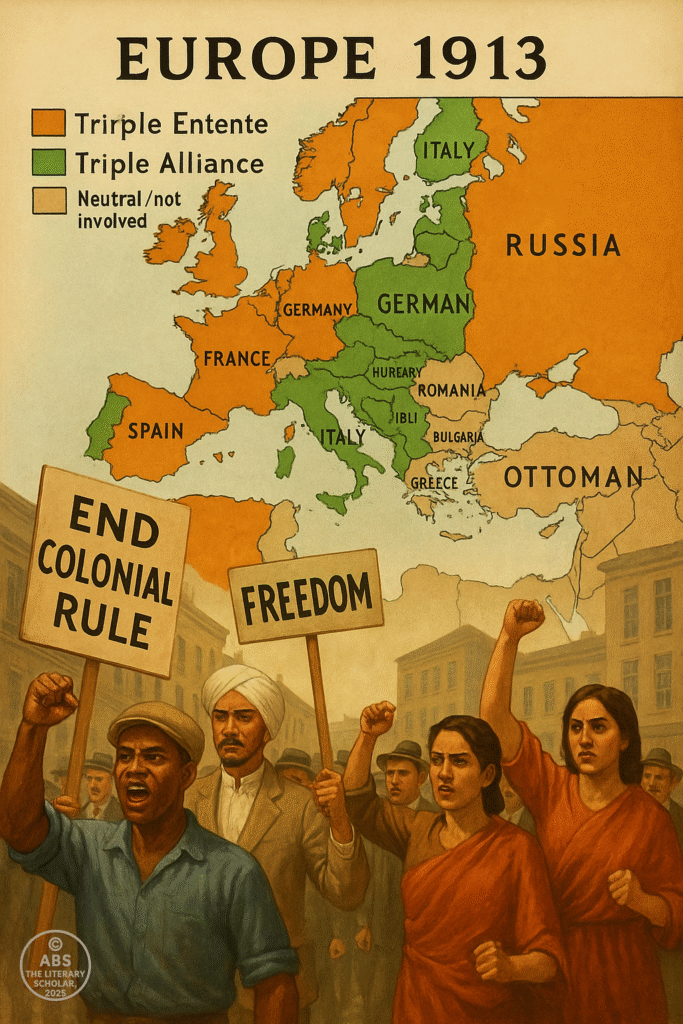

But beneath this bright skin of optimism lay a spreading bruise. Victorian moral values, so long the scaffolding of public life, were fading. Industrialization, once the engine of empire, now exposed the growing machinery of alienation, inequality, and exhaustion. The cities grew faster than the hearts could comprehend. Colonial empires began to strain and splinter, even as their rulers staged ceremonies of eternal rule. In the cathedrals of philosophy, a darker pronouncement echoed—Nietzsche had declared, “God is dead,” and the tremor of that death rumbled beneath every pulpit, every classroom, every page.

The world was not merely changing—it was accelerating. Speed became the new law of existence. Thought, travel, commerce, and conflict—everything quickened. In this whirring atmosphere, artists and writers began to revolt. The Victorian novel, stately and slow, seemed inadequate to the pulse of modern life. Realism’s surface detail felt shallow beside the storms of the inner world. Traditional verse—metered, mannered, and moral—sounded hollow. Aesthetic innovation was no longer luxury—it became necessity.

Writers began to fracture form in order to capture fracture itself. Thomas Hardy, in his later works, mourned the vanishing spirit of rural England. Yeats turned from nationalism to myth, from reason to revelation, building symbols where certainties had collapsed. The Imagists, with Ezra Pound at the helm, demanded clarity, sharpness, and brevity—poetry stripped to the bone. Stream of consciousness emerged not as technique, but as witness—to memory, to trauma, to the unrelenting press of thought.

All of this unfolded against a world edging toward disaster. Nationalist movements smoldered beneath imperial facades. Alliances grew rigid, arms stockpiled, and an uneasy diplomacy papered over the mounting tension. The machinery of war had been built; only a trigger was missing. Few imagined that by 1914, the world would fall into catastrophe—shattering the very certainties on which it had so confidently stood.

Modernism was not born in peace, but in unease. It emerged from a world no longer sure of its gods, its order, its language, or itself. The pages that follow in Part 1 walk through that restless, brilliant, unraveling moment—the last dance of an empire, the first steps into an abyss lit by electricity, poetry, and the flicker of a coming storm.

The Last Gasps of Victorianism

It is an enduring irony of history that what appears most solid is often already beginning to dissolve. The dawn of the 20th century carried such an irony in its heart: the Victorian world, seemingly entrenched in its morality, empire, and sense of progress, was already breathing its last even as the Edwardian morning broke. One queen’s funeral, one new king’s ascension, and the cultural mood began to shift—not with fanfare, but with the subtle, insidious tremors that announce deeper upheavals.

Queen Victoria’s death in January 1901 was not merely a national event; it was a civilizational punctuation mark. The long 19th century of faith, industry, and imperial certainty seemed to close with her. The British Empire, still sprawling across continents, carried the visible burden of success but the invisible seeds of exhaustion. In the metropolises of Europe and America, the old pillars of moral confidence and scientific rationalism were already under question, even as they continued to be ritually affirmed.

Literature, always the most sensitive of cultural barometers, had sensed this twilight long before political discourse would dare to speak of it. By the early 1900s, the grand Victorian novel—a vehicle of social realism, moral edification, and humanist faith—had begun to feel heavy with its own conventions. The three-volume form, the omniscient narrator, the tightly woven plots that reinforced social order—all were becoming increasingly estranged from the fractured experience of modern life.

Thomas Hardy’s late novels, particularly Jude the Obscure (1895), had already staged a quiet literary revolt. Hardy’s bleak portrayal of human suffering, institutional cruelty, and the indifference of the universe scandalized Victorian readers and signaled a decisive rupture. Jude’s despairing cry—“So that’s the end of it! The Church — the Law — custom — all closing in against one poor man!”—might well have served as an epitaph for the 19th-century faith in progress and justice.

Similarly, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) offered a dark mirror to the imperial project. In the voice of Marlow, confronting the moral void behind colonial conquest—“The horror! The horror!”—Conrad unveiled not only the hypocrisy of empire but the more profound disintegration of Western moral certainty. That the heart of European civilization could contain such darkness was a revelation many were unwilling to confront.

Yet the cultural establishment clung to old forms and ideals. The Edwardian era, inaugurated under King Edward VII, often presented itself as a final flourishing of Victorian grace—a world of elaborate manners, imperial pageantry, and moral rhetoric. In literature, figures like Rudyard Kipling still celebrated the imperial mission, while the Edwardian stage continued to favor polished drawing-room comedies. Oscar Wilde’s death in 1900 symbolized another kind of passing: the end of a certain aesthetic flamboyance that had thrived in the late Victorian fin de siècle.

But beneath this surface, tensions multiplied. The rise of industrial capitalism, the grinding poverty of urban slums, the growing restlessness of colonial subjects, and the nascent movements for women’s suffrage all pressed against the brittle façade of Edwardian complacency. The literature of the time, particularly among more perceptive writers, began to register these fractures.

The stage offered an especially fertile ground for this emerging disquiet. George Bernard Shaw’s plays—Mrs Warren’s Profession (1893, but performed only in the 20th century) and Major Barbara (1905)—attacked the moral hypocrisies of capitalism and charity. Shaw’s wit was no mere entertainment; it was a scalpel cutting through Victorian cant. “The greatest of evils and the worst of crimes is poverty,” declares Undershaft in Major Barbara, a line that would have scandalized the polite Edwardian conscience.

Meanwhile, the poetic tradition itself was caught between inertia and innovation. Many poets continued to write in the ornate, rhetorical style of the late 19th century, but younger voices were beginning to chafe against such constraints. A new hunger for clarity, precision, and psychological depth would soon give rise to the Imagist movement, though its first stirrings in this prewar period were still underground.

Politically, too, the old certainties were eroding. The British Empire faced increasing resistance from Ireland and India; the Boer War had revealed the vulnerabilities of imperial power. In Europe, the assassination of the Russian Tsar’s ministers, the unrest in the Balkans, and the emergence of anarchist movements signaled a world in ideological flux. The social question—how to reconcile industrial capitalism with human dignity—haunted political debates and echoed in the novels of H. G. Wells and Arnold Bennett, both of whom depicted a society in uneasy transition.

Above all, the great unspoken anxiety of this period was a spiritual one. The 19th century had ended with a bruised confidence in human progress and divine order. Nietzsche’s stark declaration—“God is dead.”—had not been absorbed so much as evaded. In literature, one hears the echo of this unresolved crisis in the haunting, often elegiac tones of Hardy, in the moral uncertainty of Conrad, and in the searching, symbol-laden poetry of W. B. Yeats, who would soon begin to weave his mythic system in response to this very void.

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,” Yeats would write in 1919—but the sense of approaching dissolution was already palpable in the years before 1914. Writers felt it in their bones; their works became less about certainties and more about the search for new forms capable of expressing a fragmented reality.

Thus, the last gasps of Victorianism were less a serene farewell than a convulsive, uneasy passage. Literature in this twilight zone became a site of struggle—between form and freedom, convention and innovation, complacency and conscience. The Modernist wave was gathering far beyond the horizon, but its first ripples—restless, questioning, and dark—were already lapping at the edges of the Edwardian world.

The 20th century had arrived—but it did not come in peace. It came with a haunting question: if the old gods were dead, what stories could replace them? Literature was about to embark on its most radical transformation yet.

Science, Speed, and the Modern Imagination

The modern world was not born gently; it arrived with a roar of engines, a flicker of electric light, and an unsettling new conception of time and space. The early 20th century unfolded beneath the restless hum of technological acceleration. What steam had begun in the 19th century, the spark and wire now carried forward with ferocious momentum. To the artist and writer standing at the threshold of this new century, the universe itself seemed to be spinning faster, more chaotically, and with unnerving implications for the human soul.

Einstein’s 1905 annus mirabilis papers, particularly the theory of special relativity, did not merely redefine physics; they ruptured the comfortable Victorian understanding of reality. Time was no longer an absolute, nor was space. The reassuring mechanical universe of Newton gave way to a vision where simultaneity was relative and the observer inextricable from what was observed. Though Einstein’s equations were opaque to most writers, the philosophical shockwaves were not. The very fabric of experience appeared to have lost its solidity, and literature began to reflect this new uncertainty.

At the same moment, the conquest of the air and the harnessing of electricity transformed human life. The Wright brothers’ first flight in 1903 was a brief event, but it signaled that speed, once the preserve of thought and poetry, was becoming a physical reality. Telegraphy had already annihilated the time lag between distant points; now, the airplane and the automobile promised to collapse space itself. The London of Hardy and Dickens, once traversed by horse-drawn cab and pedestrian pace, now echoed with the chug and clatter of motorcars. Streets grew more dangerous, skies more mysterious, and the very idea of distance seemed quaint.

Cinema, the youngest of the arts, flickered into life around this period, further altering the collective imagination. The moving image compressed time and space, fragmented narrative, and trained audiences to accept montage and discontinuity — a skill that would later serve readers of Modernist literature well. Virginia Woolf, observing the cinema with fascination, would later note that “the past could be unrolled, scenes could be fastened together by the whim of the projector.” The very grammar of narrative was being rewritten in the darkened theatres of London and Paris.

In this age of acceleration, the human body itself became a subject of anxious fascination. The machine threatened to outpace and even replace the organic. The Futurist movement, born in Italy but resonant across Europe, openly celebrated the aesthetics of speed, steel, and violence. “We declare that the splendour of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed,” proclaimed Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto (1909). This mechanical rapture would find fewer echoes in English letters, but the sense of being caught between flesh and metal haunted many writers.

D. H. Lawrence, in works such as Women in Love, captured this ambivalence. His industrial Midlands were places where nature and machine collided with toxic force: “The eternal battle between the mechanistic and the vitalistic,” as he would describe it. The human spirit seemed both empowered and endangered by the technologies it had unleashed.

At a deeper level, science’s most disquieting contribution to the literary imagination was its erosion of the human centrality in the cosmos. Darwin had already displaced humankind from the centre of creation; now, quantum theory (emerging by 1911) suggested that the very particles of matter operated by principles of uncertainty and indeterminacy. The universe was not a grand, stable edifice but a seething field of probabilities and flux.

The modern novelist, confronted with this shifting ground, could no longer pretend to offer a neat, linear narrative. Traditional cause and effect seemed a poor match for a world where even time and identity had grown ambiguous. The stream-of-consciousness techniques pioneered by Dorothy Richardson, later refined by Woolf and Joyce, were literary counterparts to this scientific upheaval — capturing the subjective flux of inner experience rather than the comforting march of external events.

Poetry, too, began to mirror this new tempo. Where Victorian poets had relied on stately cadences and orderly rhyme, the emerging voices of Modernism sought sharper, starker forms. The Imagists, soon to be championed by Ezra Pound, would insist that poetry should be “direct treatment of the ‘thing’ whether subjective or objective” and should avoid superfluous words. Behind this aesthetic lay the same cultural impulse that drove scientific precision — a desire to strip away illusion and confront the fractured truth of modern reality.

Yet beneath the surface celebration of progress, a countercurrent of dread was palpable. The very inventions that dazzled the public also harboured the seeds of mass destruction. Chemical industries, advanced metallurgy, and the mechanization of warfare were already making their sinister presence felt. By 1914, the world would learn that the same ingenuity that built the airplane and the cinema could also produce the machine gun and the chlorine cloud.

Thus, the early 20th-century literary imagination oscillated between exhilaration and anxiety. Science and speed had transformed the world beyond recognition — but at a price. The comforting old narratives of cosmic order and human centrality had been swept away. In their place stood a universe of flux, a city of electric light and iron, a human consciousness increasingly fragmented and unsure of its place.

Literature would not — could not — remain untouched. The coming generation of writers would grapple with this altered reality, forging new forms to express a new condition. The age of the stable narrator, the predictable plot, and the moral resolution was ending. The age of fractured consciousness, ambiguous truths, and temporal distortion was dawning.

And as the modern world gathered speed, its writers sensed—often before their readers—that this acceleration would not end in peace.

The Mind Unveiled — Freud and Psychology

At the turn of the 20th century, a far more subversive revolution than Einstein’s relativity or the Wright brothers’ flying machine was quietly gathering force — one that would forever alter how literature conceived of the human soul. This revolution did not emerge from a laboratory or a battlefield, but from a dim consulting room in Vienna, where Sigmund Freud, armed with little more than a couch and a probing curiosity, began to map the dark continent of the mind.

When Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams in 1900, it was as if a forbidden door had been flung open in the house of Western thought. The conscious mind — the seat of reason and selfhood so long celebrated by Enlightenment and Victorian writers — was revealed to be but a fragile crust over a seething ocean of drives, fears, and desires. Beneath the polished narrative of the self lay the dreamwork of the unconscious, where forbidden wishes spoke in symbols and displaced images.

Freud’s discoveries sent shockwaves through European culture, and literature, ever attuned to the subterranean currents of human experience, was quick to absorb the implications. No longer could the novelist or the poet rely upon the transparent, rational self beloved of Victorian moralists. Identity itself was now a fractured, unstable phenomenon — a precarious narrative composed by forces beyond the author’s or the character’s conscious grasp.

Modernist fiction, in particular, proved to be the ideal laboratory for exploring these insights. Even before Freud’s theories became widely known in literary circles, certain writers had already intuited the inner fragmentation he described. Henry James, whose late style often rendered psychological nuance with obsessive precision, anticipated many Freudian concerns with repression and double consciousness. In The Turn of the Screw (1898), the very ambiguity of the narrator’s perception becomes a site of psychological horror: are the ghosts real, or projections of a disturbed mind?

But it was with the true high Modernists — Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Marcel Proust — that Freud’s shadow fell most powerfully across the literary imagination. The stream-of-consciousness technique, which these writers variously pioneered, can be seen as a narrative analogue to Freud’s method of free association. In abandoning linear, external narration, they sought to capture the flux of thought, memory, and desire as it welled up from below the threshold of consciousness.

Consider Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925), in which Clarissa Dalloway’s perceptions and memories swirl in an unbroken current, the boundaries of past and present dissolved by the associative leaps of the mind. “What does the brain matter,” Woolf once wrote, “compared with the heart?” — but in truth, her novels probe both relentlessly, revealing the layers of fear, regret, and longing that conventional realism had left uncharted.

Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) takes this project further still, offering not only an unfiltered flow of thought but the polymorphous play of the unconscious upon language itself. In Molly Bloom’s famous closing soliloquy, the narrative voice descends into a stream of bodily rhythms and erotic reverie — a bravura demonstration of the Freudian insight that sexuality and repression are central to psychic life. “Yes I said yes I will Yes” — the final words echo both the affirmation of desire and the circular logic of unconscious repetition.

Poetry, too, began to register this new depth of interiority. T. S. Eliot, a close reader of psychoanalytic texts, suffused The Waste Land with symbols of sexual anxiety, spiritual desolation, and cyclical trauma. The poem’s fractured voices and allusive density mirror a psyche in crisis — one where memory and desire churn beneath the surface of a shattered modernity. “I will show you fear in a handful of dust,” declares the speaker — a line that might well serve as a poetic gloss on Freud’s entire project.

Yet Freud’s impact extended beyond technique; it offered Modernist writers a new thematic preoccupation. The repression of desire, the formation of neuroses, the haunted residue of childhood experience — all became fertile ground for literary exploration. No longer was sin the exclusive terrain of the moralist; it was now the symptom of a deeper psychic conflict. Characters such as Lawrence’s tortured lovers, Kafka’s persecuted figures, or Woolf’s Septimus Smith emerge less as agents of moral choice than as battlegrounds of the unconscious.

At the same time, Freud’s theories resonated with a broader cultural anxiety. If human action was shaped by irrational forces, how could one trust the great narratives of progress and reason that had underpinned Western civilization? The horrors of mechanized warfare — soon to erupt in the trenches of World War I — would render this question all the more urgent. The traumatized soldier, reliving the past in flashbacks and nightmares, would come to embody the very collapse of the rational, unified self that Freud had diagnosed.

Critics of psychoanalysis were quick to point out its limitations — its sexual reductionism, its clinical jargon, its tendency toward determinism. But in literature, the influence of Freud’s discoveries was transformative. Even those who rejected his theories could not escape the altered understanding of the mind they had unleashed. The unconscious had become an inescapable presence in the modern imagination — a silent interlocutor beneath every word, every gesture, every narrative thread.

By 1914, the literary landscape was already marked by this deeper sense of inner complexity and instability. The old certainties of character and plot, of motive and resolution, had begun to dissolve under the pressure of new psychological insights. Modernism’s search for new forms — fragmented, fluid, impressionistic — was as much a response to this internal revolution as to any external change.

And as the guns of August began to thunder across Europe, writers would soon confront a world in which the psychic wounds of war would demand still more radical modes of expression. The mind had been unveiled — and there was no turning back.

The Crisis of Faith and Meaning

The dawning of the 20th century was accompanied not merely by new inventions and new psychological discoveries, but by a profound and spreading malaise of the spirit. If the Victorian age had ended in a triumphant crescendo of moral earnestness and imperial confidence, the modern age began with a hollow echo. Beneath the bright promise of scientific progress and political rhetoric lay a mounting sense that the great metaphysical anchors of Western civilization had come loose. Faith — in God, in Reason, in Progress — was in crisis. The literature of the early modern period would become one of its richest fields of expression.

The first tremors of this upheaval had already been felt in the preceding century. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) had, by implication, dethroned humanity from its privileged position in the cosmos. Evolution, with its indifferent mechanisms of natural selection, offered no place for providence or design. The scientific worldview it inaugurated spread inexorably through public consciousness, undermining the biblical vision of a created and purposeful universe.

By the time the Edwardian writers came of age, this crisis of faith had deepened. Nietzsche’s infamous proclamation — “God is dead.” — reverberated through European thought, not as a triumph of secularism, but as a chilling diagnosis of cultural decay. In The Gay Science (1882), Nietzsche’s madman laments: “Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon?” The terrifying freedom — and moral void — implied by this vision haunted the intellectual and literary world alike.

Literature responded not with simple atheism, but with a complex register of loss, irony, and spiritual hunger. Thomas Hardy, perhaps the last great Victorian novelist to carry his vision into the modern age, captured this disillusionment with relentless bleakness. In God’s Funeral (1908), he writes:

“And, tricked by our own early dream

And need of solace, we grew self-deceivers,

Our making soon our maker did we deem,

And what we had imagined we believed.”

Hardy’s poetry and fiction became a graveyard of lost faith, where fate replaced providence, and cosmic indifference stared coldly upon human striving. The Victorian moral order, rooted in Christian teleology, could no longer be sustained.

Yet if faith in divine providence was eroding, so too was confidence in the secular surrogates that had begun to replace it. The cult of Progress, so central to the 19th century’s self-image, began to ring hollow. The march of industrialization had not banished poverty or inequality; the marvels of modern technology often served imperial conquest and class oppression rather than universal uplift. As early as the Edwardian period, writers sensed that the machine might devour its maker.

E. M. Forster’s early novels hover uneasily between inherited values and modern doubt. In Howards End (1910), Margaret Schlegel’s injunction — “Only connect!” — becomes both a moral plea and an acknowledgment of deepening fragmentation. The novel’s vision of an England torn between soulless industrialism and fragile humanism reflects the broader cultural tension: if the old religious and moral frameworks no longer held, what new basis for meaning could be found?

Poets and playwrights turned increasingly toward myth, irony, and tragic vision in response to this vacuum. W. B. Yeats, disillusioned with both rationalism and Christian orthodoxy, constructed his own elaborate mystical system drawn from the occult, Eastern philosophy, and Irish legend. “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold,” he would famously write in The Second Coming (1919), capturing the apocalyptic mood that had been building even before the Great War.

Drama, too, began to reflect this spiritual disorientation. Henrik Ibsen’s late plays, widely read and performed in England, unmasked the hypocrisies of bourgeois morality and exposed the emptiness behind social conventions. Bernard Shaw, though a rationalist, used his plays to confront the moral vacuity of capitalist and imperialist ideology, while figures like Maeterlinck experimented with symbolist drama that evoked the ineffable and the uncanny rather than presenting moral certainties.

Meanwhile, T. S. Eliot, who would become one of Modernism’s central voices, absorbed both philosophical pessimism and spiritual yearning into his early work. The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1915), with its ironic allusions and paralyzed speaker, offered a miniature portrait of modern spiritual paralysis. “I have measured out my life with coffee spoons,” laments Prufrock — a devastating image of existence reduced to triviality in the absence of grand narratives or sustaining beliefs.

The novel itself began to fracture under the strain of representing a world without moral consensus. Stream-of-consciousness narration, temporal distortion, unreliable narrators — all became tools not merely of aesthetic experimentation, but of existential honesty. The modern psyche could no longer be depicted through the clear moral arcs of Victorian fiction; it was now a site of ambiguity, irony, and loss.

And yet, this crisis of faith was not purely destructive. For many writers, it cleared a space for new forms of inquiry and vision. Myth, art, eroticism, and personal integrity emerged as partial answers to the void left by collapsed religious and moral systems. Eliot would later find a redemptive vision in Four Quartets; Yeats sought it in his esoteric system; Woolf and Joyce found it in the intricate weave of subjective experience and aesthetic form.

As Europe drifted toward war, the spiritual crisis deepened. The old gods had vanished; the new idols — nationalism, mechanized progress, scientific materialism — would soon reveal their own monstrous faces. In this interregnum of belief, literature became the most vital forum for confronting the question that haunted the modern age: if there is no divine order, no moral absolute, no secure progress — then what, if anything, can give human life its meaning?

The writers of the early 20th century would not provide simple answers. But in their restless search, their unflinching gaze into the void, they gave the modern literary imagination both its deepest anxieties and its highest ambitions.

Urban Alienation — The Modern City as Maze

If the human spirit was already shadowed by metaphysical doubt and psychological fragmentation at the turn of the century, nowhere did this condition find more vivid expression than in the modern city. The city was the crucible of modernity — a site of both exhilarating possibility and profound alienation. It embodied the restless energies of industrial capitalism, imperial ambition, and technological progress, yet also revealed their human costs in the form of anonymity, spiritual emptiness, and moral dislocation. For Modernist literature, the city became not merely a setting but a central metaphor for the fractured modern condition.

London, Paris, Berlin, Dublin, New York — these urban centres swelled with unprecedented speed in the early 20th century. Immense tides of rural migrants and immigrants fed their growth. Factories roared, electric lights erased the night, and the once familiar rhythms of time and space dissolved into a ceaseless flux of crowds, noise, and movement. The stable, organic communities of the Victorian imagination were giving way to a labyrinthine, impersonal metropolis.

Writers who had once celebrated the city’s energy began to register its darker implications. Charles Baudelaire, the proto-modernist poet of Paris, had already articulated the experience of the urban flâneur — the detached observer drifting through the indifferent crowd. Walter Benjamin, reflecting on Baudelaire’s vision, would later describe modern urban life as a condition of perpetual distraction and fragmentation. The individual became a fleeting presence in the crowd — simultaneously surrounded and isolated.

This paradox — the loneliness of the individual amid the mass — would become a defining theme of early 20th-century literature. T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922) crystallized the urban malaise with haunting precision:

“Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.”

The echo of Dante’s Inferno in these lines is no accident. For Eliot, the modern city is a spiritual wasteland, its inhabitants reduced to ghostlike figures in a mechanized, dehumanized world. The flow of traffic and commerce masks a deeper disconnection — from nature, from tradition, from the self.

James Joyce’s Dublin — the city that he famously vowed to recreate with such fidelity that it could be rebuilt from the pages of Ulysses — is similarly a site of paralysis and spiritual stagnation. In Dubliners (1914), Joyce portrays lives stunted by provincial inertia and urban anonymity. “Every night as I gazed up at the window I said softly to myself the word paralysis,” confesses the young narrator of The Sisters. The city becomes a kind of trap — a place where the aspirations of its inhabitants rot unfulfilled.

Franz Kafka’s Prague, though less explicitly foregrounded in his fiction, infuses his vision of bureaucratic nightmare and existential dislocation. In works like The Trial (1925), the city is rendered as an endless maze of offices, courts, and corridors — spaces in which the individual is powerless, lost amid an impersonal and inscrutable system. Kafka’s urban landscapes are not mere settings but architectures of dread, reflecting the alienation and anxiety of the modern subject.

Even those who celebrated certain aspects of urban modernity recognized its psychic toll. Virginia Woolf’s London is both luminous and overwhelming. In Mrs Dalloway, the city’s vibrant surfaces — motorcars, advertisements, chiming clocks — contrast sharply with the inner anguish of characters like Septimus Smith, whose war trauma isolates him amid the bustling streets. Woolf captures the fractured temporalities of urban experience: “The leaden circles dissolved in the air,” she writes of Big Ben’s chimes — a haunting image of time slipping away in a city that knows no rest.

The modern city thus emerged in literature as a space of sensory overload and spiritual impoverishment. Its cacophony drowned out the inner voice; its labyrinths mirrored the fragmented psyche. Where the Romantic poets had found transcendence in nature, the Modernists found disorientation in the metropolis.

Yet this very disorientation spurred formal innovation. The fractured narratives of Joyce, Woolf, and Eliot mimic the experience of moving through the modern city — a series of fleeting impressions, interrupted associations, and sudden shifts of perspective. Stream-of-consciousness prose became the literary analogue of the urban flâneur’s wandering gaze.

Moreover, the city’s chaotic diversity forced a reckoning with cultural multiplicity. The old hierarchies of class, race, and gender were increasingly unsettled in the urban crowd. For some writers, this multiplicity was a source of creative energy; for others, a harbinger of cultural disintegration. The modern city was both a stage and a crucible — where the self might be remade or undone.

By 1914, as Europe stood on the brink of war, the literature of urban alienation had already laid bare the psychological costs of modernity. The city — once the emblem of human progress — had become the emblem of modern estrangement. Its streets teemed with life, yet offered no true communion. Its lights blazed ever brighter, even as the shadows lengthened.

And in the minds of the poets and novelists who chronicled this paradox, the modern city would remain an abiding symbol of the fragmented, anxious, and profoundly human search for meaning in an increasingly impersonal world.

Imagism and the New Poetic Revolution

If the modern city taught writers that the old rhythms of experience had shattered, poetry itself would soon echo this fracture in its form and voice. The ornate, rhetorical verse of the Victorians — with its measured cadences and moral certainties — had become a hollow vessel in an age of fragmentation, urban flux, and existential doubt. A new century demanded a new poetics: leaner, sharper, more truthful to the jagged textures of modern life. It was this demand that gave birth to Imagism — a movement that would help propel poetry into the Modernist era.

Imagism began not as an institutional school, but as an instinctive revolt. At its heart lay a rejection of what Ezra Pound called “the doughiness” of late Victorian poetry — its verbal excess, sentimentality, and grand abstractions. In their place, Imagist poets sought directness, precision, and economy. They believed that the image — not the moral or the narrative — should be the poem’s core. And in an age where the surrounding culture was saturated with empty rhetoric and political bombast, this aesthetic was not only literary, but moral.

Pound, ever the restless polemicist, would become Imagism’s most vocal champion. His pithy 1913 statement captured the essence of the movement:

“1. Direct treatment of the ‘thing’, whether subjective or objective.

2. To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation.

3. As regarding rhythm: to compose in sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of the metronome.”

Behind these deceptively simple principles lay a radical new conception of poetic language. Poetry was no longer to be an elaborate tapestry of elevated diction and metaphor, but a scalpel that cut clean to the experience itself. The poet was to observe with the precision of a scientist, the intuition of a mystic, and the economy of a modern machine.

H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), one of Imagism’s finest practitioners, exemplified this ethos in her crystalline lyrics. Her poem Oread (1914), with its spare yet vivid language, invites the sea to become a forest of waves:

“Whirl up, sea —

whirl your pointed pines,

splash your great pines

on our rocks,

hurl your green over us,

cover us with your pools of fir.”

Here is a poetics of immediacy — one in which the image is not described, but enacted. The sea is not compared to a forest; it becomes one in the reader’s sensory imagination. The poem dispenses with introductory clauses, narrative scaffolding, and moral commentary. It is pure presence, distilled.

Such an approach resonated deeply with Modernist anxieties about language and truth. In an era where political slogans and journalistic clichés proliferated, the Imagists sought a language that resisted falsification — a mode of saying that refused the easy consolations of rhetoric. In a world of lies and distortions, perhaps the clean, hard image could serve as an anchor of authenticity.

Ezra Pound’s own In a Station of the Metro (1913) — often cited as the quintessential Imagist poem — embodies this aspiration in just two lines:

“The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.”

Here is the modern city, transformed by the poet’s gaze into an aesthetic revelation. The crowd becomes a fleeting image of beauty amid the grime of the urban landscape. The poem’s very brevity becomes an ethical stance — a refusal to embellish, to moralize, to sentimentalize. It offers a flash of clarity amid the modern blur.

Yet Imagism was not merely a technical movement. It represented a deeper cultural longing — a desire to find moments of unmediated perception in a world where inherited meanings had collapsed. The fragmentary image became a way of salvaging meaning from the ruins.

T. E. Hulme, an often-overlooked figure in the movement, expressed this ethos bluntly: “Man is an extraordinarily vain, sentimental, self-centred animal, who is always seeking for the picturesque and the romantic…The great aim is accurate, precise, concrete description.” In an age of imperial bombast and nationalist myth-making, this commitment to precision was itself a form of moral resistance.

Imagism’s influence would far outlast its brief organizational life. By the mid-1910s, the movement had already begun to fracture under the pressures of personality and aesthetic difference. But its core principles — precision, concision, musicality — would become foundational to Modernist poetry.

T. S. Eliot, though not formally an Imagist, absorbed its lessons deeply. The vivid fragments of The Waste Land bear the Imagist imprint, even as they transcend its scope. William Carlos Williams would take the Imagist ethos into American poetics, insisting: “No ideas but in things.”* Even Wallace Stevens — a poet of philosophical complexity — retained Imagism’s reverence for the image as the site where thought and sensation converge.

In the larger trajectory of modern literature, Imagism marked the turning of the poetic gaze from the grand abstractions of 19th-century verse to the fractured textures of 20th-century experience. It taught poets to see the world with unflinching clarity — and to trust that the image itself, properly rendered, could evoke the unspoken depths of modern life.

In an era when the language of faith had faltered, the language of ideology had grown suspect, and the self had become a site of contradiction, the Imagist image stood as a small, hard beacon — a moment of presence in a sea of flux. The poetic revolution it sparked was, in the deepest sense, a spiritual one.

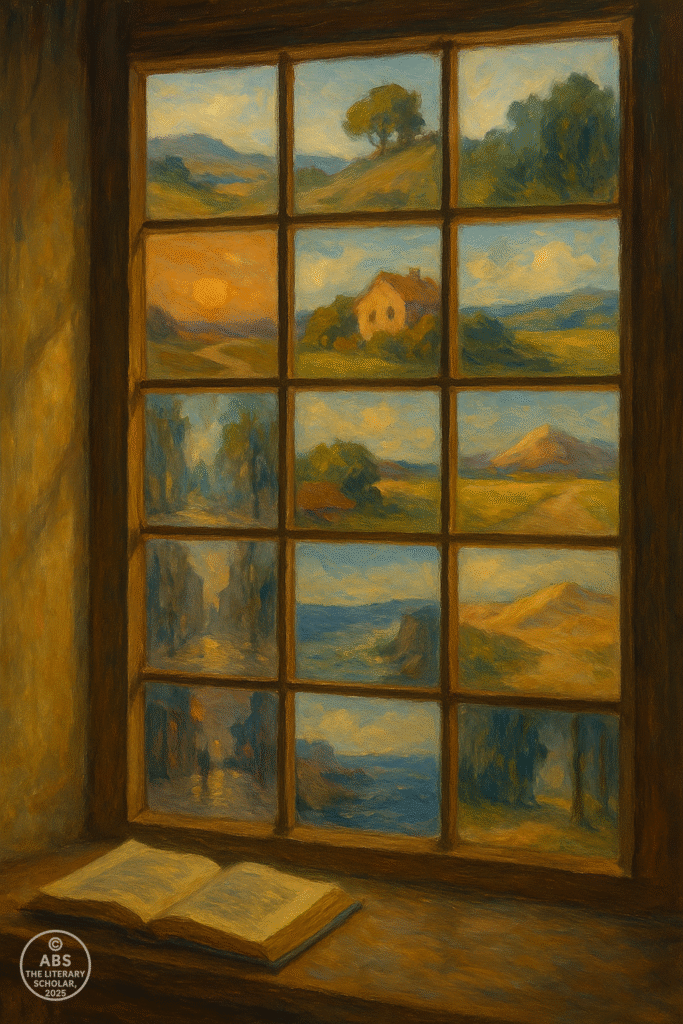

Toward the Modernist Novel

If the modern poem had begun to shed its rhetorical skin and seek a new, leaner voice, the modern novel faced an even greater challenge. The traditional novel had been, in many ways, the Victorian century’s grandest literary instrument — a form that promised panoramic social vision, moral clarity, and narrative coherence. But as the new century unfolded — with its fractured psychology, disenchanted metaphysics, and vertiginous pace of life — this very coherence came to seem an aesthetic lie.

The Modernist novel arose not merely from a desire to innovate, but from a deeper sense of formal crisis. How could the novel — with its conventions of omniscient narration, linear plot, and stable character — do justice to a world where time itself was unstable, the self unknowable, and society in flux? Modernist fiction was born, in part, from the refusal to pretend that the old narrative certainties still held.

Henry James, standing at the threshold of this transformation, had already begun to erode the conventions of the realist novel in his late works. His “house of fiction” no longer possessed clear windows through which the reader could survey an ordered world. Instead, it was a structure of shifting perspectives, shadowed interiors, and unreliable narrators. In The Ambassadors (1903), the very moral coordinates of the narrative dissolve amid the ambiguities of experience: “Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to,” declares Strether — a credo that evades easy moral categorization.

Joseph Conrad, too, transformed the novel into a meditation on the limits of knowledge and language. Heart of Darkness (1899), though composed on the cusp of the century, is already a profoundly Modernist text. Its nested narration, temporal disjunctions, and obsessive self-consciousness foreground the act of telling itself as a site of uncertainty. “We live, as we dream — alone,” Marlow reflects — a bleak epiphany that haunts not only the colonial enterprise but the very fabric of narrative authority.

Virginia Woolf would later recognize that the 19th-century novel’s portrait of life — with its solid furniture and moral scaffolding — could no longer capture modern experience. In her 1919 essay Modern Fiction, she castigated the conventional novelists of her time for their “tyranny of plot” and their refusal to engage with the inner life. “Life is not a series of gig lamps symmetrically arranged,” she insisted. “Life is a luminous halo, a semi-transparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of consciousness to the end.” The task of the novelist was to render this shimmering, unstable flux.

The stream-of-consciousness technique, pioneered by Dorothy Richardson in Pilgrimage (1915 onward), and refined by Woolf and James Joyce, emerged as a radical means of capturing this inner flow. The Modernist novel ceased to be a transparent window onto an external world; it became a medium through which the rhythms of thought, memory, and sensation could be evoked. Narrative time fractured into subjective time; linear causality gave way to associative drift.

Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) marked a decisive break with realist convention. Its early chapters immerse the reader in the sensory immediacy of childhood — a world of sounds, colors, and half-understood words. “Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road,” begins the novel — a sentence that collapses the boundary between child and narrator, between memory and fiction.

By the time of Ulysses (1922), Joyce had transformed the novel into a vast laboratory of form. Every device of traditional narration was interrogated and reinvented. The book’s 18 episodes adopt a dazzling array of styles — from catechism to pastiche, from interior monologue to mythic parallel. Beneath this stylistic play lies a profound reimagining of narrative itself: the everyday is rendered epic; the momentary is infused with eternity; the fragment replaces the whole.

Woolf’s own fiction — particularly Mrs Dalloway (1925) and To the Lighthouse (1927) — pursued a parallel path. In these novels, plot recedes before the waves of memory and perception. The ticking of Big Ben in Mrs Dalloway does not measure objective time; it marks the ebb and flow of inner lives. “What is this terror? what is this ecstasy?” thinks Clarissa Dalloway — a question that resonates through the novel’s luminous evocation of modern consciousness.

The Modernist novel also embraced linguistic experimentation as a response to the inadequacy of received forms. In Finnegans Wake (1939), Joyce shattered language itself, forging a polyglot dream-text that mirrored the unconscious mind’s protean flux. While such extremes remained singular, the broader Modernist project sought to make language new — to strip it of dead conventions and restore its capacity to evoke the fractured textures of modern experience.

Politically and ethically, this formal innovation was not neutral. The conventional realist novel had often colluded with the ideologies of empire, patriarchy, and bourgeois order. By dissolving narrative authority and embracing polyphony, the Modernist novel implicitly challenged these hierarchies. It became a space where marginalized voices, submerged desires, and repressed histories could surface — if only in fragmentary, haunted form.

Yet the Modernist novel was not an exercise in nihilism. Its formal daring arose from a profound ethical commitment: to represent life as it is — fractured, uncertain, but charged with fleeting moments of truth and beauty. In refusing the false coherence of traditional narrative, the Modernist novel honored the complexity of modern existence.

As Europe stumbled toward war, this literary revolution was still gathering force. The old story of the novel — as a mirror of society or a vehicle of moral edification — had ended. A new story had begun: the novel as a shattered mirror, each fragment catching a glint of the ungraspable real.

Politics, Empire, and the Gathering Storm

Even as the Modernist imagination turned inward—probing the fractured psyche, testing the limits of language—the outer world was darkening with forces that no writer could ignore. The early years of the 20th century were not only an age of psychological and aesthetic revolution; they were also a period of mounting political crisis, in which the old imperial order began to tremble beneath its own contradictions. And as the clouds gathered, Modernist literature became increasingly attuned to the deep structures of power, violence, and disintegration that underlay the shimmering surfaces of modern life.

The British Empire, at its zenith in 1901, appeared outwardly invincible. The sun never set upon it, and the language of moral mission and civilizational superiority still adorned imperial discourse. Yet beneath this veneer of confidence lay deep currents of unrest and decay. The Boer War (1899–1902), fought at the dawn of the new century, had already exposed the moral and military vulnerabilities of imperial Britain. Reports of concentration camps and civilian suffering punctured the imperial myth of righteous conquest.

In India, Ireland, Egypt, and across Africa, nationalist movements simmered and sometimes flared. Writers sensitive to the pulse of history could feel the tension in the air. W. B. Yeats’s Ireland was a land divided—between colonial subjugation and a yearning for cultural and political selfhood. His early poetry often evoked a dreamlike Celtic past, but as the nationalist struggle intensified, his verse grew darker, more political:

“Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.”

Yeats’s poetry bears witness to the anguish and complexity of nationalist passion—a passion both necessary and dangerous. The Easter Rising of 1916 and its violent suppression would later inspire his famous meditation “Easter 1916”, with its ambivalent refrain: “A terrible beauty is born.” Such poetry reveals the Modernist impulse to confront, not evade, the political tempests of the age.

Elsewhere, the imperial project itself became a subject of fierce literary interrogation. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness—though published before the century’s turn—gained renewed relevance as the darker realities of empire came into focus. Its haunting vision of European hypocrisy and moral corruption struck a resonant chord in an era increasingly disillusioned with imperial rhetoric. “The conquest of the earth,” Marlow muses bitterly, “which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.” Conrad’s indictment of imperial violence and spiritual hollowness became an essential part of the Modernist conscience.

The gathering storm, however, extended far beyond the colonial periphery. In Europe itself, the old diplomatic order—rooted in fragile alliances and dynastic interests—was showing fatal cracks. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914 would trigger a cataclysm, but the underlying tensions had been building for years: militarization, ethnic nationalism, imperial rivalry, and the festering wounds of past conflicts.

Writers and intellectuals sensed the coming rupture with varying degrees of clarity and dread. Thomas Mann, reflecting later on pre-war Europe, wrote of “the peculiar tension, the extraordinary sense of expectancy” that pervaded the years before 1914. In England, E. M. Forster’s Howards End can be read as an elegy for a liberal humanism already under siege. The novel’s plea—“Only connect!”—rings all the more poignant against the backdrop of a society drifting toward fragmentation and violence.

Even the language of Modernist aesthetics was shaped by the era’s political disquiet. The disjointed syntax, abrupt transitions, and multiple voices of Modernist prose and poetry reflected not only a fractured psyche but a fractured world. T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, though written after the war, draws upon prewar images of cultural decay and spiritual exhaustion that had already haunted the literary imagination.

At the same time, the rise of mass politics and ideological extremism cast a long shadow over artistic freedom. The growth of socialist, anarchist, and proto-fascist movements posed urgent questions about the artist’s place in a turbulent public sphere. Could literature remain autonomous in a world where slogans drowned out subtlety and violence silenced dissent?

For some writers, aesthetic innovation itself became a form of political resistance. To fracture the old narrative forms, to shatter the illusion of coherence, was to resist the false unities imposed by imperial propaganda and authoritarian ideologies. The dissonances of Modernist art mirrored the dissonances of modern politics—not as a retreat from reality, but as a deeper engagement with its complexities and contradictions.

Yet for others, the political world threatened to overwhelm the aesthetic. The challenge was to remain honest—to bear witness to the gathering storm without succumbing to dogma or despair. In this sense, the Modernist commitment to ambiguity, irony, and multiplicity was not an evasion of moral responsibility, but an assertion of intellectual integrity in an age of ideological certitude.

As Europe edged toward the abyss, Modernist literature stood at a precarious crossroads. The artist could neither withdraw into pure aestheticism nor surrender to crude political instrumentalism. The task was more difficult—and more necessary: to render, in language true to its fractured time, the complexity of a world on the verge of convulsion.

When the war finally came, it would sweep away not only empires and armies, but also the last illusions of an ordered, meaningful modernity. In its wake, literature would face the even graver challenge of speaking to a world irrevocably broken—and yet still yearning for words that might make sense of the silence.

Foreshadowing the Deluge

It is one of history’s bitter ironies that the years preceding the Great War were, in many quarters, suffused with a peculiar brilliance — a sense of cultural flowering even as political catastrophe loomed. The Belle Époque shimmered with confidence and invention; the arts danced on the edge of radical transformation. Yet beneath this luminous surface, sensitive writers and thinkers heard a different music: a slow, ominous drumbeat signaling the approaching collapse of the old order. The storm was not unforeseen — though the scale of its devastation would surpass all imagining.

Literature, more attuned than politics to the tremors beneath the cultural crust, became a medium of prophetic unease. Even as Modernist forms advanced — stream of consciousness, Imagist verse, polyphonic narrative — the content of this innovation often expressed a profound anxiety about the civilization that had bred such brilliance. The aesthetic revolutions of the pre-war years were born not of cultural optimism, but of crisis — a recognition that the old frameworks of meaning could no longer bear the weight of modern experience.

In poetry, W. B. Yeats stood among the most prescient voices. His early mysticism gave way to a stark apprehension of impending chaos. Though The Second Coming would be written in the war’s aftermath, its central vision was gestating long before 1914:

“Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.”

The widening gyre — Yeats’s symbol of historical cycles spinning toward collapse — captures with haunting precision the mood of a Europe increasingly unable to contain its own centrifugal forces. Nationalism, militarism, imperial rivalries, and mass politics had combined to create an unstable equilibrium — one that no fragile diplomacy could sustain.

In fiction, too, the signs of impending rupture multiplied. Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent (1907) offered a chilling portrait of political nihilism and urban terrorism — a shadowy underworld of anarchists and double agents where violence fed on despair, and the line between state power and revolutionary terror grew dangerously thin. Conrad, who had long explored the moral emptiness beneath imperial and capitalist triumphalism, now turned his gaze upon the home front, revealing a European society rotting from within.

E. M. Forster’s Howards End (1910) may seem, on the surface, a novel of domestic England — yet beneath its lyrical prose lies a sharp awareness of social fragmentation and the failure of liberal humanism. The Schlegel sisters’ idealism struggles against the brutalities of class, commerce, and imperial arrogance. The novel’s unresolved tensions mirror those of a nation teetering on the brink of an unspoken crisis.

In the visual arts, the break with past certainties was equally radical. Cubism, Futurism, Expressionism — all fractured the static perspectives of 19th-century representation. Space, time, and form were reimagined — not merely for aesthetic effect, but in response to a deeper cultural sense that the old Newtonian cosmos had dissolved into relativistic flux. The confidence of Enlightenment reason had given way to the vertigo of modern uncertainty.

Yet perhaps the most poignant foreshadowings of the coming deluge were not in manifestos or philosophical treatises, but in the minor, everyday images that haunted the Modernist imagination. T. S. Eliot’s early poems — before the full rupture of The Waste Land — already thrum with quiet dread:

“Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherised upon a table;”

The paralyzed patient — a grotesque inversion of the Romantic evening sky — becomes a fitting emblem for a civilization numbed by its own contradictions, incapable of coherent action even as disaster approaches.

This paralysis extended beyond the individual psyche to the political realm. The elaborate alliance system that bound Europe’s great powers in uneasy peace was a fragile, brittle construct. Diplomats moved through their rituals; monarchs paraded in gold-braided finery; the popular press fed nationalist fervor to restless populations. But behind the choreography lay the fatal logic of escalation. When the assassination at Sarajevo in June 1914 provided the spark, the great machinery of mobilization and retaliation moved with grim inevitability.

Writers who survived the war would later look back upon the pre-war years with a mixture of nostalgia and bitter clarity. Virginia Woolf, reflecting in Moments of Being, spoke of “the whole world’s feeling that things would never be the same again after August 1914.” The rupture was not merely military or political; it was epistemic. The war would destroy not only bodies and cities, but the very idea of a stable, coherent modernity.

In retrospect, the foreshadowings were everywhere — in the dissonances of Imagist verse, in the broken chronologies of experimental fiction, in the haunted music of Symbolist poetry, in the jagged canvases of Modernist art. The very innovations of pre-war literature can be read as acts of mourning for a world already slipping into darkness.

And when the guns of August roared to life, the Modernist project would be forced to confront its greatest challenge: to make language adequate to the ruins, to speak to a world that had shattered its own illusions. The story of that literary reckoning belongs to the next phase of Modernism — to the poetry of the trenches, the broken voices of postwar fiction, the waste land of European culture.

But here, at the end of this first part of the modern journey, we stand with those pre-war writers gazing into the abyss — their words already echoing with the unspoken knowledge that the deluge was coming, and that nothing in literature — or in life — would ever be quite the same again.

The Restless Dawn: Literature on the Edge of the Modern

The first scroll closed with the world holding its breath. A world where Victorian certainties were slipping into shadows, where poets trimmed their verses to match a disjointed reality, and where the very shape of thought was beginning to fracture. Before the trenches opened and the century bled its innocence, literature had already foreseen the rupture.

Part 1 was the prelude—not just to war, but to modernity’s existential murmur.

A soft descent into the silence before the storm.

And into that silence, writers wrote.

Signed,

The Professor’s Desk

The Literary Professor

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance