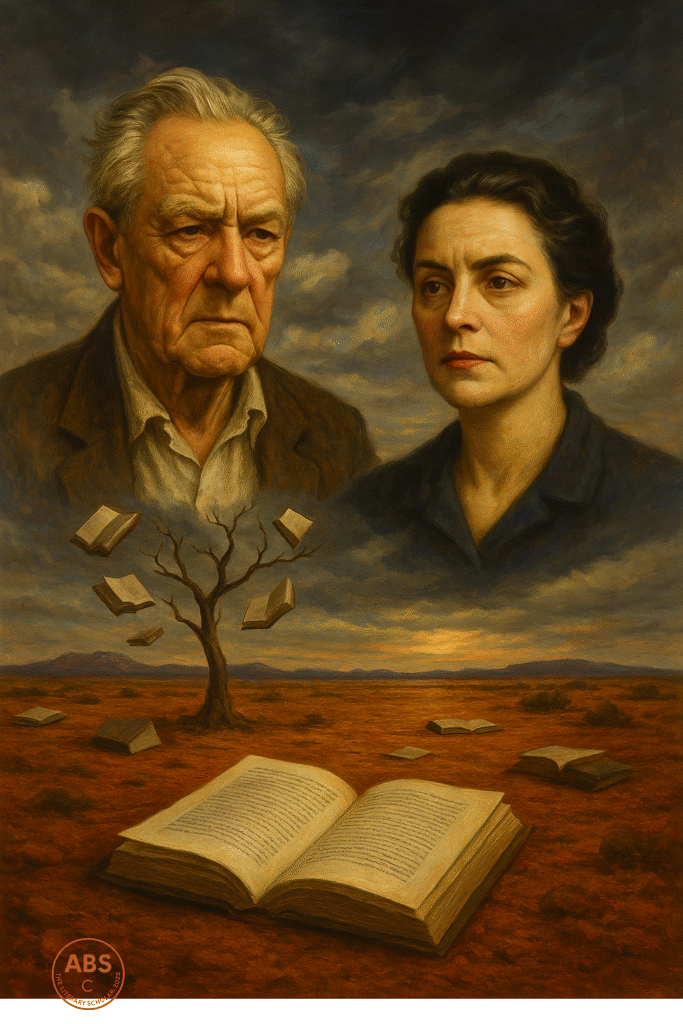

Patrick White, Christina Stead, and the novelists who turned isolation into high art and existential dread.

By ABS, who believes that Australian literature discovered its soul somewhere between a sheep paddock, a philosophical crisis, and a very dry wit.

After the bush ballads faded and the swagmen wandered off into metaphor, Australian literature experienced a literary glow-up. It put away the rhyming couplets, grew a backbone, and started questioning not just the landscape—but the entire human condition.

And like most glow-ups, this one came with dramatic flair, internal confusion, and the need to win at least one international prize before anyone at home took it seriously.

Welcome to mid-century Australian literature: where isolation met intellect, heatwaves met existentialism, and the country finally realized that bleak was beautiful—especially with a touch of sarcasm.

Patrick White: Nobel Laureate, National Enigma, Literary Hurricane

Let’s begin with Patrick White, the man who made spiritual despair fashionable in Australia long before Instagram filters.

His prose is famously dense, his themes famously difficult, and his attitude toward critics famously lethal. In other words: he was exactly what Australian literature needed—a myth-maker with no interest in being liked.

Key works include:

The Tree of Man – domesticity meets the divine in a small farm, with no manual and a lot of mud.

Voss – German explorer + desert + philosophical unraveling = national metaphor.

The Solid Mandala – sibling rivalry meets symbolic overload.

White was Australia’s first and only Nobel Prize winner in Literature (1973). Naturally, the country was slightly annoyed at first, then confused, then proud. Like parents discovering their child became famous for interpretive dance.

Christina Stead: Literary Genius, International Vagabond, Emotional Wrecking Ball

If Patrick White was the high priest of Australian alienation, Christina Stead was its psychological assassin.

Her novel The Man Who Loved Children (1940) is often cited as a masterpiece of domestic horror disguised as literature. Based loosely on her own childhood (because therapy is expensive), it explores family dysfunction with such precision that readers have reported needing a glass of something strong afterward.

Stead wrote with fury, elegance, and no patience for sentimentality. Her characters simmer, her prose seethes, and her psychological insight is so deep it might qualify as a diagnosis.

She also spent much of her life abroad—because being brilliant and Australian in the mid-20th century meant fleeing to be taken seriously.

Randolph Stow, Elizabeth Jolley, and the Quiet Storm

The mid-century period also produced a wave of quiet rebels—authors who didn’t shout, but whispered things so sharp they still echo.

Randolph Stow (To the Islands, The Merry-Go-Round in the Sea) tackled identity, Indigenous spirituality, and existential crisis—all in deceptively calm sentences.

Elizabeth Jolley, who bloomed late but weirdly, wrote about misfits, loneliness, and polite emotional breakdowns. Imagine Muriel’s Wedding rewritten by Kafka with tea.

These authors weren’t trying to entertain. They were trying to translate Australia’s inner landscape—the part hidden behind the barbecue.

Themes That Cried in the Dust (But Very Eloquently)

Isolation as both setting and psyche

Family as a poetic prison

The land not as a hero, but as a silent, judging roommate

Language as something to bend until it breaks beautifully

Religion, fate, madness—and awkward dinners

This wasn’t the hearty, rhyming, beer-loving literature of yesteryear. This was literature that stared at the void and took notes.

Australia’s Identity Crisis Gets Intellectual

The post-war years brought big questions:

Who are we if not just England’s sandy cousin?

Can we write about emotions without making the sheep nervous?

Is it possible to be profound in a place with this many flies?

These writers answered yes—then buried that yes under metaphor, trauma, and linguistic gymnastics.

Australia, once written in wagons and wool, was now written in angst and ambiguity.

ABS puts down the scroll with quiet reverence, letting the outback winds carry it across the dusty plains—where someone, somewhere, is probably having an existential breakdown while making tea.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Scholar

Who believes that once Australia started writing its own psychological weather report, the literary forecast got deliciously unpredictable.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance