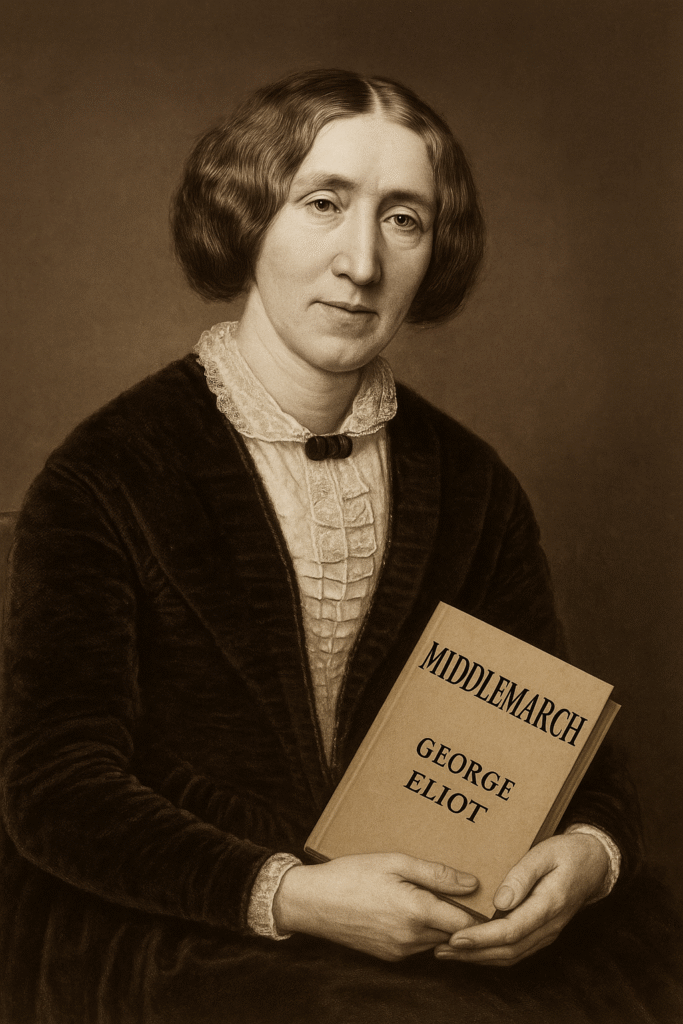

By ABS, The Literary Scholar

(Who firmly believes that in Middlemarch, no one minds their business, and that’s precisely the point)

If you’ve ever thought your town was too nosy, too dramatic, or too obsessed with marriage and mortgages, rest assured: George Eliot did it first and better in Middlemarch.

Published in eight volumes between 1871–72 (because Victorian readers had patience and no internet), Middlemarch is not so much a novel as it is a literary ecosystem. A sprawling, intricate, deeply psychological exploration of ambition, love, reform, failure, and the deeply British art of suffering politely.

“If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow.”

Yes. In Middlemarch, even the grass is emotionally over-invested.

This is not your average Victorian novel with a corset and a crisis. It’s a social surgery, performed with elegant prose and moral forceps. George Eliot—née Mary Ann Evans—peels back the curtain on small-town idealism with surgical precision, a tender grimace, and just enough sarcasm to remind you she knew how silly people could be… even while loving them.

Dorothea Brooke: The Saint Who Married a Footnote

Let’s start with the crown jewel of disappointment: Dorothea Brooke.

She’s smart. She’s serious. She dreams of doing good in the world.

So, naturally, she marries a dried-up academic old enough to be her uncle who’s writing The Key to All Mythologies—a book that will never be finished and is already outdated.

“He had the kind of mind that would have made him a good monk in the 12th century.”

That’s Eliot, casually demolishing Casaubon’s entire existence with a single line.

Dorothea wants purpose. What she gets is footnotes and spiritual dehydration. Casaubon, in turn, wants obedience, reverence, and perhaps a tomb inscription that reads “Intellectually Threatened by His Wife.”

When he dies (spoiler: unlamented), Dorothea is left with freedom, money, and the moral burden of being too good for everyone around her.

Tertius Lydgate: Science, Pride, and the Worst Financial Decisions

Lydgate enters Middlemarch with ambition: he’s a doctor! A man of science! A believer in reform and reason!

Naturally, he falls in love with the town’s shallowest ornament: Rosamond Vincy, who has the inner depth of a teaspoon and the shopping habits of a Victorian influencer.

“She was a woman who had never entered into the soul of another being.”

Again, George Eliot doesn’t kill her characters with cruelty—she just quietly sets their lives on fire with psychological realism.

Lydgate’s downfall isn’t just Rosamond’s spending or the town’s resistance to change. It’s his own pride. He wants greatness but is too proud to ask for help. And in Middlemarch, that’s a one-way ticket to failure with lace curtains.

Fred Vincy and Mary Garth: The Only Couple Worth Rooting For

Amidst all the ambition and moral paralysis, Fred and Mary are the quiet heart of the novel.

Fred is charming but aimless. Mary is practical, grounded, and slightly judgmental—in other words, perfect. Their romance is slow, subtle, and entirely grounded in personal growth. Which, for a Victorian novel, is basically pornography.

Fred doesn’t slay dragons. He gets a job. He improves. He learns humility. And Mary waits—not passively, but with the kind of active standards that make you love her.

Bulstrode, Scandal, and Hypocrisy—The Town’s Favorite Pastimes

Ah yes, Mr. Bulstrode. A religious banker with a dark past and a talent for moral contradiction.

Eliot uses Bulstrode to explore how tightly hypocrisy clings to virtue, and how public morality often serves as a mask for private panic. His past comes back to haunt him in the form of gossip, suspicion, and the kind of small-town judgment that burns hotter than any theological hell.

Bulstrode is not a villain. He’s Middlemarchian—a man who wants to be good, but finds himself trapped by choices, appearances, and the sinking suspicion that his soul has been mortgaged along with his bank.

The Genius of Eliot: Making the Ordinary Epic

Eliot doesn’t need duels, betrayals, or dramatic deaths to hold your attention. She gives you bills, proposals, sermons, resignations, wills, and turns them into moral battlegrounds.

Middlemarch isn’t about what happens. It’s about why it matters.

And it matters because every life here is lived with intention, with self-delusion, with hope, with grief—quietly, fully, and painfully. Eliot captures the tragedy of a mismatched marriage, the disillusionment of ambition, the aching beauty of doing the right thing too late.

“It is a narrow mind which cannot look at a subject from various points of view.”

In other words, Middlemarch demands patience. And empathy. And the ability to hold multiple truths at once. It’s like life—only with better prose and fewer emojis.

And somewhere, ABS, The Literary Scholar, puts down The Key to All Mythologies, raises an eyebrow at the cost of emotional idealism, and whispers, “No one ever died from unrequited love in Middlemarch—but they definitely aged badly from it.”

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

(Still choosing Fred and Mary over every brooding Byronic alternative)

(Still convinced Casaubon is what happens when men fear intelligent women)

(And who knows George Eliot didn’t just write characters—she wrote consequences)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance