By ABS, The Literary Scholar

(Who firmly believes no baby name ever escapes its baggage—especially if it comes with a Russian novelist and parental expectations)

In the tender chaos of immigration, one thing always seems simple: the name. A syllable. A sound. A label. But when Bengali parents in America name their child after a Russian author who once survived a self-induced near-death literary experience, it becomes abundantly clear—names are never just names.

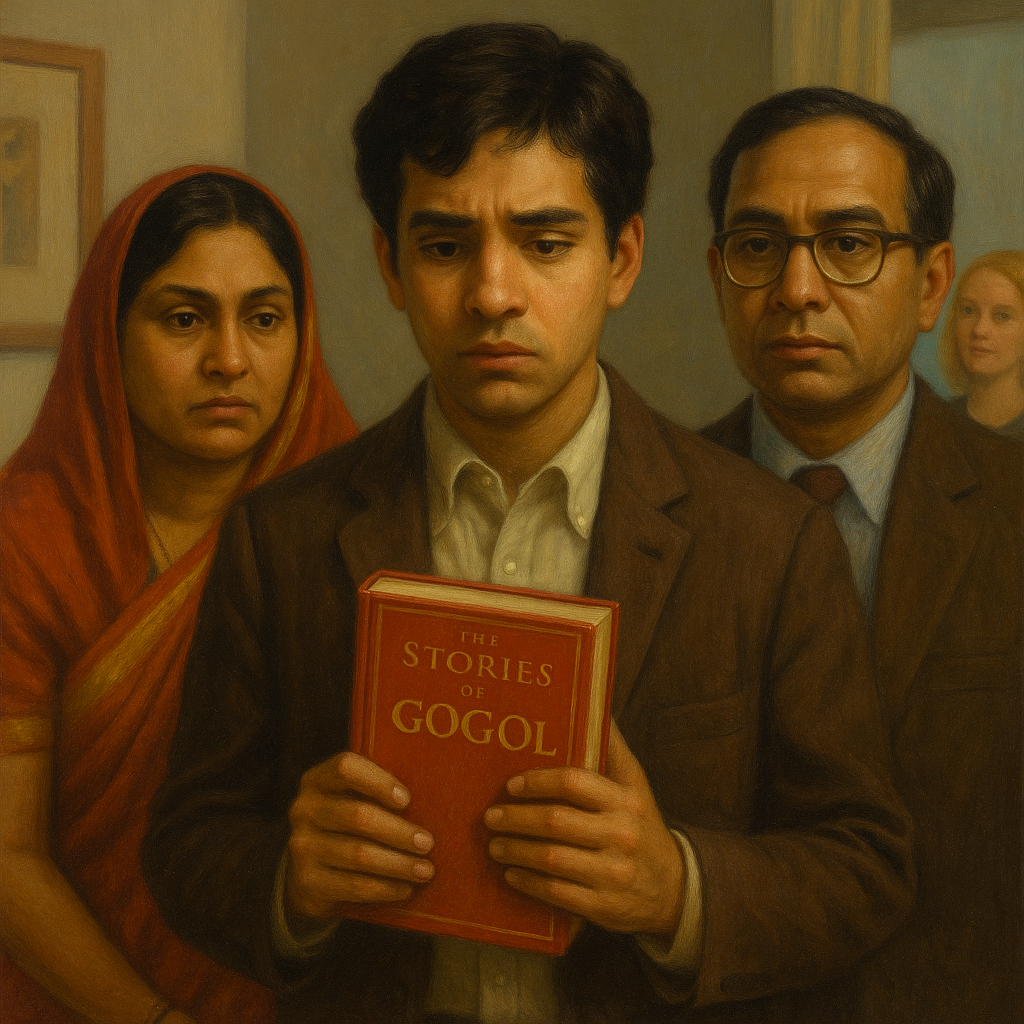

Enter: Gogol Ganguli, the unwitting protagonist of Jhumpa Lahiri’s beautifully understated novel The Namesake. A boy born in Massachusetts to Bengali immigrants, carrying a name neither Russian nor Bengali nor American, and growing up like a walking identity crisis wrapped in khadi.

This is not a story of melodrama. It is a story of melancholy dressed as politeness—that silent discomfort immigrants learn to wear like a neatly pressed shirt at a job interview.

The Gangulis Arrive: Confusion Begins at Customs

Ashoke and Ashima Ganguli arrive in America armed with saris, Tagore, and an encyclopedic knowledge of how things are not done back home. They enter a world of microwaves and muffled loneliness. Ashoke is an MIT-educated engineer. Ashima is a poet-in-hiding who learns to microwave frozen peas with the same reluctance she once reserved for meeting in-laws.

When their firstborn arrives, they find themselves trapped by bureaucracy: they need a name. And not a good, Sanskrit-approved, Bengali-family-vetted name. A hospital form name.

So Ashoke, drawing from the ghost of his past—the train accident he survived while reading Nikolai Gogol—writes down “Gogol.”

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is how generational trauma becomes a birth certificate.

The Name That Didn’t Fit in a Lunchbox

Gogol grows up in a house where people still remove shoes at the door, mail wedding gifts in rupee-stuffed envelopes, and celebrate Durga Puja in living rooms that smell of mustard oil and Vicks. But outside, he is just “Gogol,” a name that earns him snickers at school, puzzled stares from teachers, and endless mispronunciations.

“He hates that his name is both absurd and obscure, that it has nothing to do with who he is, that it is neither Indian nor American but of all things, Russian.”

Poor boy. He wasn’t even named after Nikolai the man, but after a literary accident. Imagine telling your friends at school that you’re named after someone your dad was reading when a train nearly killed him.

“It’s not even a name,” he thinks. “It’s a joke.”

And it is. The kind that makes you laugh softly at first… and then just hurts.

Immigrant Parenting 101: Dual Lives, Dual Plates

While Gogol tries to Americanize himself—rock music, blonde girlfriends, architecture school—his parents cling to the sanctity of Rice, Roti, Rabindranath.

Ashima’s greatest grief isn’t just homesickness—it’s the slow erasure of everything familiar. Her sorrow is subtle: it unfolds in grocery aisles, snow-covered mailboxes, and the way she folds saris with no one to admire them.

Ashoke, on the other hand, is a quiet stoic who names his son after a Russian author as a thank-you to fate and then never tells him why. Classic immigrant move: bury the emotion, decorate it with silence.

Gogol Becomes Nikhil: Because Sometimes You Need a Rebrand

Like any good postcolonial protagonist, Gogol reaches a breaking point. One day, he decides to reclaim his narrative—by legally changing his name to Nikhil.

It’s a logical move. “Nikhil” is suave, digestible, LinkedIn-friendly. A name that blends in better at parties with hors d’oeuvres and wine lists.

“The name feels correct. It’s a path he can follow.”

And yet… names are not masks. They’re histories. You can’t always bleach out the past with a name change. Because somewhere in the quiet corners of his mind, Gogol is still alive, still whispering from the shadows of a Russian paperback.

The Tragedy of Ashoke: The Father Who Spoke Quietly but Lived Loudly

And then comes the novel’s most tender thunderclap—Ashoke’s death.

Suddenly, the name Gogol doesn’t feel so ridiculous. It becomes a legacy, a lifeline, a memory that aches.

Gogol realizes what we all realize too late: our parents are full of stories they never told us, and we are shaped by silences we never questioned.

In naming him, Ashoke had passed on the only thing that had ever saved him—a writer’s name, a moment of chance, a scar that meant survival.

“For being a name so ridiculed, so disliked, so shed… it turns out to be the name that brings him home.”

The Romance(s): Moushumi, Maxine, and the Art of Choosing a Culture

Gogol’s romantic history could be subtitled: Confused Brown Boy Dating Catalog.

Maxine: The All-American girlfriend who serves foie gras with confidence and introduces him to dinner parties where nobody has ever cooked rice in a pressure cooker.

Moushumi: The Bengali academic who quotes Foucault, wears red lipstick, and marries him only to sabotage their marriage in a Parisian intellectual meltdown.

Both women mirror Gogol’s duality. Maxine offers assimilation. Moushumi offers tradition, wrapped in rebellion. Neither works.

Because, let’s face it—Gogol isn’t looking for a partner. He’s looking for a mirror. And that, dear reader, is a terrible burden to place on someone else.

The Ending: No Fireworks, Just Truth

Lahiri doesn’t believe in dramatic finales. The Namesake ends quietly, as it began. No existential screams. Just Gogol, alone, pulling out the book his father once gave him.

Nikolai Gogol’s collected stories.

For the first time, he decides to read them—not out of obligation, but out of longing. To know his father. To know himself. To finally claim the name he once rejected.

“The man who gave you your name, who gave you everything, is gone. And you’re left with pages.”

And somewhere, ABS, The Literary Scholar, carefully folds a worn-out name tag between the pages of Gogol’s short stories, leaves a bowl of puffed rice by the window, and writes down every name they’ve ever been called—just to remember what it meant.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

(Who believes some names are gifts, and some are lifelong essays)

(Still wondering what to do with all the inherited commas, customs, and contradictions)

(And who knows that identity, like achar, ferments over time—messy, spicy, and unforgettable)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance