Kamala Markandaya, Anita Desai, Nayantara Sahgal, Bhabani Bhattacharya—and the tea-steeped fiction of postcolonial India

By ABS, The Literary Scholar, who believes in women who penned silence into thunder and sewed metaphors into every sari fold.

Before Indian fiction got drunk on postmodernism and magic realism, it went through a rather elegant, emotionally complex phase—where characters didn’t levitate, but they did quietly break down while folding laundry or making rice. Welcome to the middle child era of Indian English Literature: the between-independence-and-globalisation years. The prose was tender, the politics personal, and the air thick with repressed emotions—and sometimes powdered turmeric.

This was the time when typewriters clacked quietly in government flats, and the characters within novels had names like Santha, Tara, Kiran, and Dev. No magical snakes. No invisible tigers. Just deeply felt silences, with a generous helping of socio-political angst.

Let’s walk into the drawing room of this literary circle, and—oh wait—someone’s already making tea.

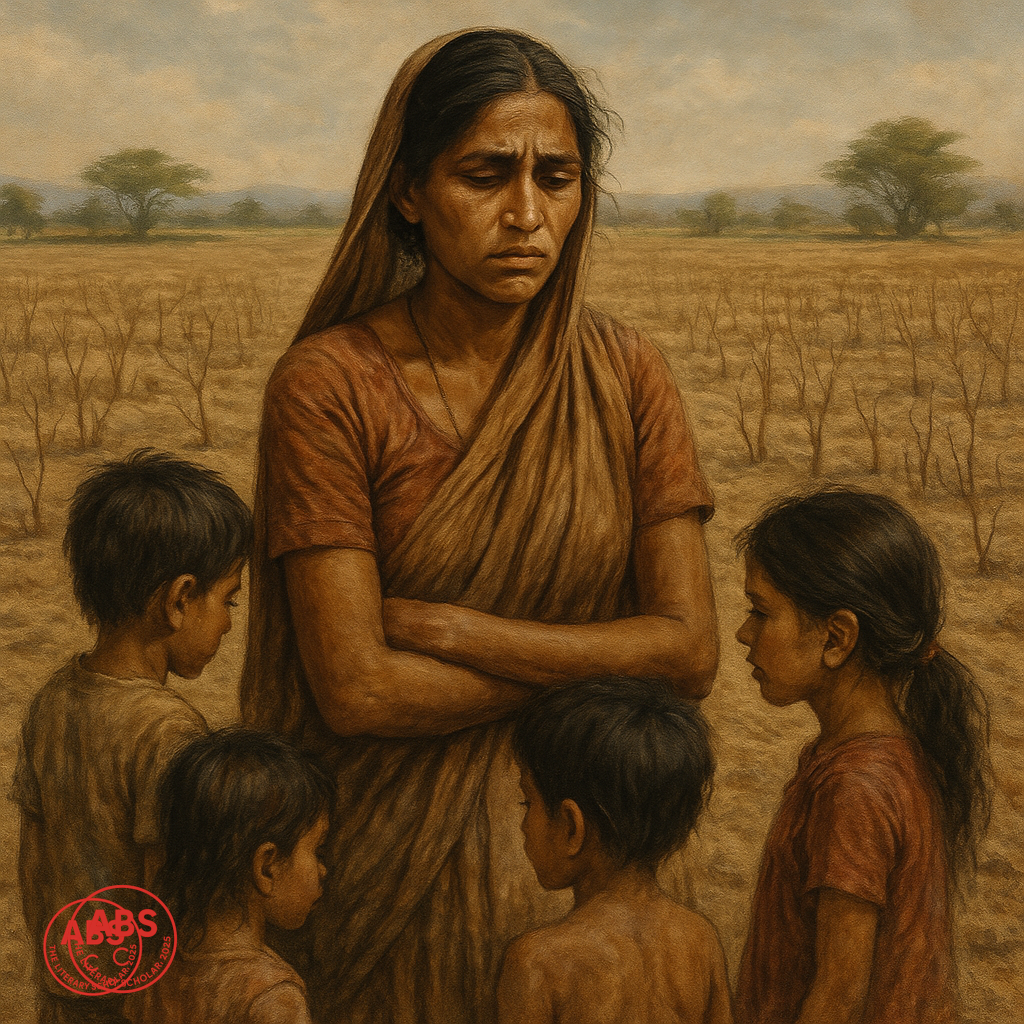

Kamala Markandaya: Of Droughts, Dreams, and Diaspora

If R.K. Narayan gave us Malgudi’s whimsical charm, Kamala Markandaya gave us the same setting—after the monsoon failed, the cow died, and someone pawned their last bronze pot.

Nectar in a Sieve (1954) isn’t a book—it’s an emotional dehydration process. The story of Rukmani, a peasant woman who watches her entire world wither like rainless crops, is told with such quiet heartbreak, you’ll start apologising to your rice cooker.

“Hope is like a bird that senses the dawn and carefully starts to sing while it is still dark.”

And that’s Markandaya—melancholy with a side of metaphysics.

In A Handful of Rice, she shifts to the city and shows us another familiar Indian setting: the hungry, jobless man standing outside a locked opportunity.

Markandaya wrote not with rage, but with resignation—and therein lay her power. She didn’t romanticise poverty. She internalised it. Her prose is soaked in sorrow, but somehow never pity. Reading her is like visiting someone grieving, who still insists on offering you a cup of chai.

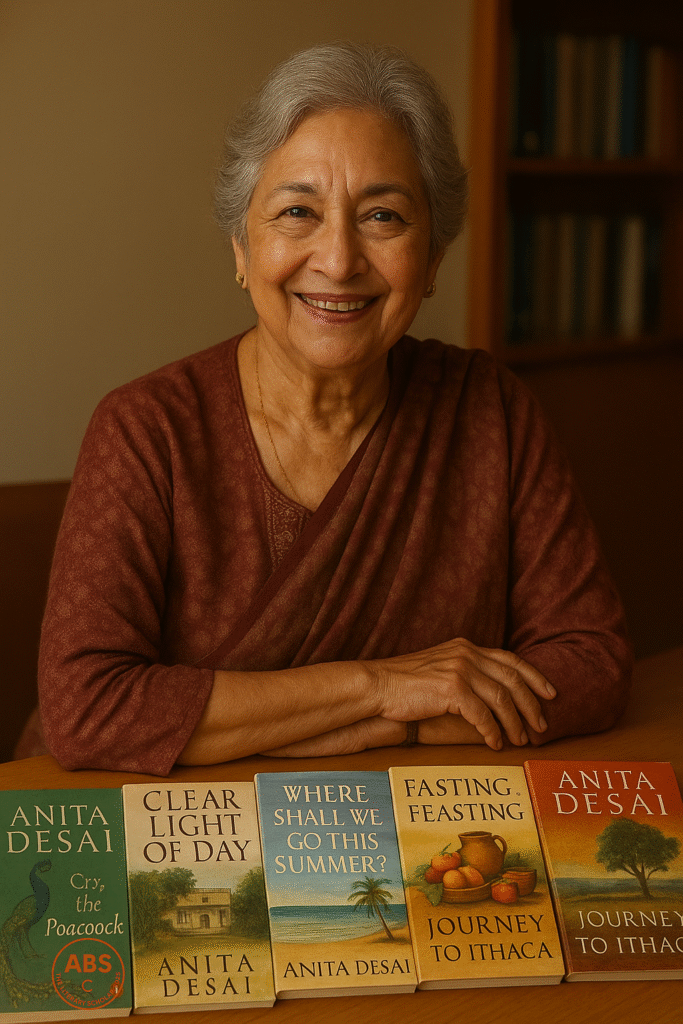

Anita Desai: Existential Dread, Now With Ceiling Fans

Now step softly into the humid, slightly musty pages of Anita Desai. She doesn’t shout. She doesn’t even raise her literary voice. But she will absolutely ruin your day in the best possible way.

Take Cry, The Peacock (1963). It begins with a woman, Maya, who hears a prediction about death—and instead of laughing it off, she spends the rest of the novel spiralling into poetic despair. It’s like Sylvia Plath took a summer job in Delhi.

“Loneliness was the punishment for having been born.”

Cheerful, isn’t it?

But that’s the Desai experience. Her writing is all about internal storms in externally peaceful houses. Clear Light of Day (1980) is essentially about a family trying to survive each other—and the Partition. It’s got everything: silence as dialogue, memory as battleground, and people who apologise with hand gestures instead of actual words.

Anita Desai’s superpower? Making psychological trauma feel like a quiet Sunday afternoon. She introduced a whole generation of Indian readers to interior monologue, which is just a fancy way of saying: “Here is 300 pages of one woman thinking about a single argument from 1972.”

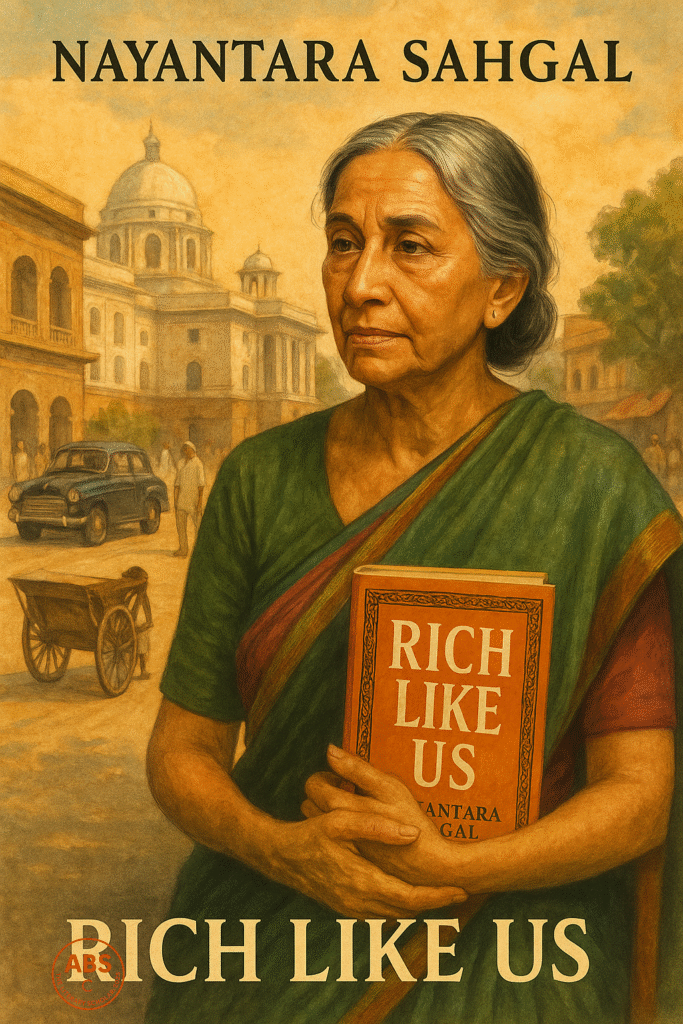

Nayantara Sahgal: Where Feminism, Politics, and Literary Grace Collided (and Gossiped Over Lunch)

Enter Nayantara Sahgal—Jawaharlal Nehru’s niece, which meant she had to deal with both national expectations and dinner party opinions.

Her prose is where Lutyens’ Delhi meets feminist rage in silk sarees. Rich Like Us (1985) explores the Emergency through the eyes of women who are navigating both political dictatorships and bad marriages. Frankly, the marriages seem worse.

“History has a way of laughing at our pretensions, especially those neatly typed in triplicate.”

She’s sharp, subtle, and devastating in her restraint. Storm in Chandigarh (1969) could’ve been about bureaucratic files, but she turns it into a tale of political tension and emotional quicksand.

Her characters are idealists, rebels, betrayed wives, and confused administrators. They quote Yeats, drink gin, and sometimes overthrow governments—usually in the same paragraph.

If Anita Desai’s characters collapse inward, Sahgal’s burn quietly, wrapped in political muslin.

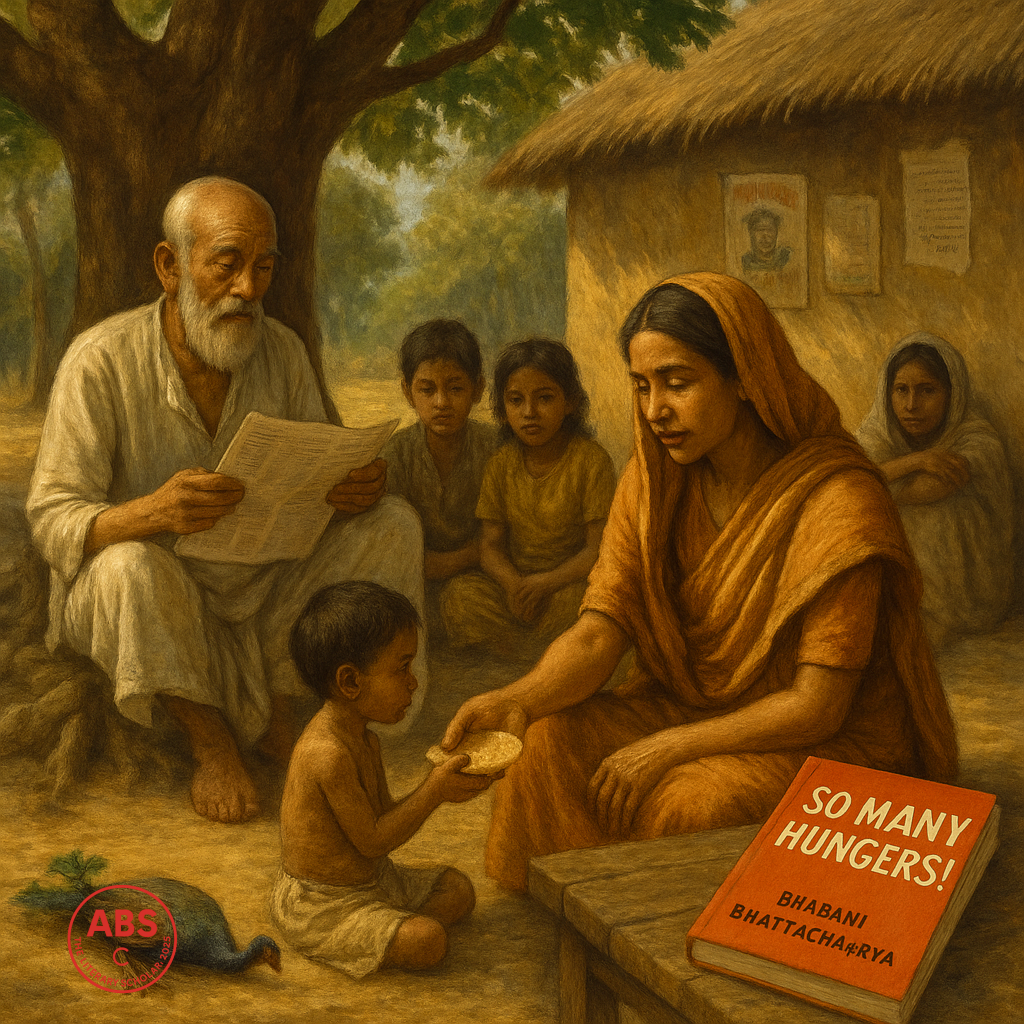

Bhabani Bhattacharya: Moral Philosophy with Mango Pickle

You’d think Bhabani Bhattacharya would be the boring one in this tea party. Think again.

So Many Hungers! (1947) isn’t just about food insecurity—it’s about conscience starvation. It’s set during the Bengal famine, and it’s as uplifting as an obituary—but he makes it beautiful.

“Man lives by bread, but also by his mind and by his dreams.”

He also gave us He Who Rides a Tiger (1955), a tale where a priest fakes a miracle to expose the hypocrisy of caste. That’s Bhattacharya: socially engaged, morally upright, and just a little cheeky.

His writing doesn’t whisper like Desai’s or philosophise like Markandaya’s—it lectures you with flair, like that uncle who quotes Gandhi before he passes you the chutney. But make no mistake—his fiction was fiercely honest.

He was the conscience-keeper of this generation, reminding everyone that just because India was free didn’t mean it was fair.

Imagined Scene: The Literary Tea Party

Let us now eavesdrop on a highly fictional gathering:

Kamala Markandaya is stirring her tea solemnly, thinking about rural displacement.

Anita Desai sighs, looking out the window at the heat waves, composing a paragraph in her head about how dust reflects inner decay.

Nayantara Sahgal has brought political gossip and intellectual shade. She’s judging everyone’s metaphors.

Bhabani Bhattacharya is trying to raise moral awareness but keeps being interrupted by the samosas.

Meanwhile, a journalist knocks and asks, “Where is the revolution?”

They all point to their typewriters.

Manohar Malgonkar (Bonus Round): Partition, Princely Problems, and the Art of Stoic Heroism

If the above writers were drinking Darjeeling, Manohar Malgonkar was probably sipping whisky with a wounded Rajput who’d just been betrayed by history. His A Bend in the Ganges (1964) is a grand narrative of India’s Partition years—full of idealists, realists, cowards, and nationalists in various states of moral collapse.

And The Princes (1963)? It’s a dry, sarcastic look at royal decay—imagine The Crown, but with more elephants and less politeness.

Malgonkar was a rarity—he didn’t do inner monologue. He did action, politics, and masculine brooding. If Desai’s characters sigh under ceiling fans, his break noses under chandeliers.

So What Did They Really Give Us?

They gave us a language of transition.

While the earlier writers dealt with Empire, and later ones exploded into diaspora disco, this group handled the hardest thing of all: reality. Post-independence wasn’t glamorous—it was awkward. And these authors knew it.

They wrote about hunger without melodrama, about madness without hysteria, about women without turning them into symbols. They were the original multitaskers: feminist, political, lyrical, philosophical—and quietly revolutionary.

They told India’s truth in lowercase, not headlines.

Their novels didn’t scream—they simmered. But if you listen closely, you’ll hear the voice of a nation learning to speak to itself. No one levitated. No one time-travelled. But someone always cried in the kitchen—and someone else always tried to understand why.

As ABS closes the scroll with turmeric-stained fingers and a raised eyebrow at yet another metaphysical simile in Desai’s prose, the room seems quieter. The typewriters are silent now, but their stories linger—like forgotten teacups in dusty bookshelves, or old letters tucked in saree folds.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

Still unsure whether that peacock cried for rain, freedom, or just better prose editing—but endlessly grateful it cried at all.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance