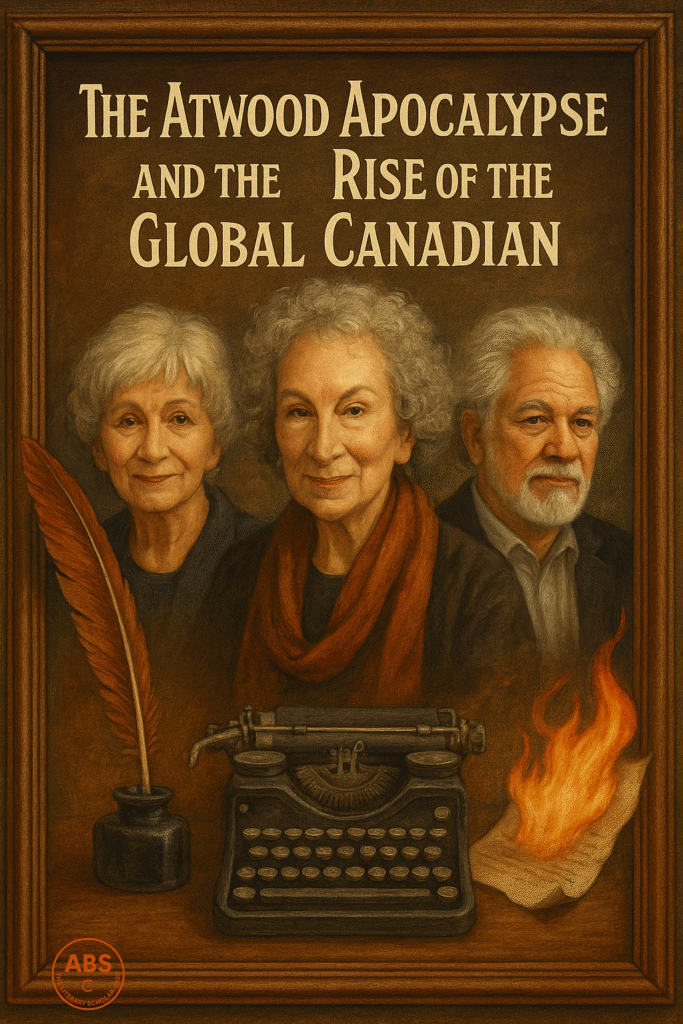

Welcome to the age of Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, Michael Ondaatje, and a literary passport that finally got stamped.

By ABS, who believes that Canadian fiction became globally relevant the moment it stopped apologizing in every sentence.

It finally happened. Canada got loud.

Well, not American loud. But definitely loud enough for the world to notice that Canadian literature had teeth—and could bite even without snarling.

Gone were the days of hushed pastoral poetry and nature metaphors that quietly died in the snow. Enter: novels with plague brides, memory bombers, and dystopias run by Puritan cosplay enthusiasts. Welcome to the golden age of CanLit—where Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, and Michael Ondaatje took the global stage, turned down the heat on politeness, and rewrote what it meant to be Canadian.

Margaret Atwood: Literary Oracle or Prophet of Doom? Yes.

There’s no starting anywhere else. Margaret Atwood is to CanLit what maple syrup is to breakfast: sticky, essential, and everywhere.

Her career began in poetry (The Circle Game, 1966), but soon turned to fiction with the subtle ferocity of a cat who’s figured out the thermostat. Her breakout, The Edible Woman (1969), poked fun at consumer culture, gender roles, and dinner—all in one go.

Then came the apocalypse du jour:

The Handmaid’s Tale (1985): Dystopia with a bonnet.

Oryx and Crake (2003): Climate collapse and gene-spliced nightmares.

Alias Grace (1996): Murder, memory, and Victorian gaslighting.

Atwood didn’t just write women—she wrote patriarchy into a corner, then painted the walls with prose so sharp it left paper cuts. And she did it all while refusing to be called a feminist writer (which is the most feminist thing one could possibly do).

She also invented the term “speculative fiction”, presumably after realizing “science fiction” would make her books sit next to aliens instead of Orwell.

Alice Munro: Queen of Quiet Chaos

If Atwood is the literary thunderstorm, Alice Munro is the snowflake that slices through steel. Her short stories are surgical in their stillness—emotionally devastating, but so polite about it you almost thank her afterward.

Known for:

Lives of Girls and Women (1971): Small-town girlhood turned epic.

The Moons of Jupiter (1982): Where family dysfunction floats in outer space.

Dear Life (2012): Final stories, and a literary mic drop so graceful it won a Nobel.

Her settings are often rural Ontario. Her subjects? Everyone you’ve ever underestimated.

Munro’s genius lies in making the ordinary feel cosmic. She writes about affairs, aging, loss, and awkward silences—and somehow makes them feel like Shakespearean tragedy narrated by a weathered schoolteacher.

When she won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2013, she didn’t throw a party. She took a nap. That’s how Canadian she is.

Michael Ondaatje: Poet of Smoke and Memory

If Canadian literature were a jazz band, Michael Ondaatje would be the saxophonist in the corner playing with his eyes closed—and still stealing the show.

A Sri Lankan-born poet and novelist, Ondaatje brought a global, cinematic texture to CanLit. His narratives blur history, memory, and myth, and his prose reads like someone taught a typewriter how to dream.

Key works:

The English Patient (1992): War, love, betrayal, and a desert full of secrets.

In the Skin of a Lion (1987): Immigrants building Toronto—with bruises and poetry.

Running in the Family (1982): Memoir as lyrical mystery.

He took CanLit out of the woods and into international waters—and made it sultry, tragic, and uncomfortably beautiful.

Others Who Crashed the Cabin Party

This era wasn’t a solo act. It was an ensemble. Enter:

Mordecai Richler – Irreverent, Jewish, Montreal-loving cynic (The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz).

Timothy Findley – Queer gothic historian of trauma (The Wars).

Carol Shields – Domestic life with existential wit (The Stone Diaries).

Robert Kroetsch – Postmodern prairie madness.

Ann-Marie MacDonald – Drama, trauma, and theatrical beauty (Fall on Your Knees).

Leonard Cohen – Because of course the guy who sang “Hallelujah” also wrote wrenching novels (Beautiful Losers is not for the faint of morals).

Guy Vanderhaeghe, Jane Urquhart, Douglas Coupland – Because no one told them novels couldn’t be both funny and emotionally damaging.

Themes in This Era: Finally, We’re Getting Interesting

Memory as myth

Feminism without footnotes

History as an unreliable narrator

Dystopias so plausible they feel like documentaries

A global Canadian identity: born in one place, shaped by another

This wasn’t just “Canadian” literature anymore—it was world literature with a maple accent. The anxieties of earlier scrolls—“Are we British? Are we American? Are we just polite shadows of bigger countries?”—were replaced by a new, confident shrug:

“We’re weird, we’re wild, and we’re writing. Try and stop us.”

The Export Era

Canadian authors were now winning Bookers, Nobels, and screen adaptations. Atwood got Hulu. Munro got Stockholm. Ondaatje got Ralph Fiennes. Even the lesser-knowns got literary pilgrimages named after them in underfunded libraries.

CanLit had become an international affair—and it did it by embracing contradiction, diversity, and the art of not being easily summarized.

ABS closes the scroll, wiping ink off a literary passport that has finally seen some stamps. Somewhere, Atwood frowns approvingly from a dystopian distance.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Scholar

Who believes that once CanLit embraced memory, metaphor, and a bit of menace—it finally became irresistible.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance