Challenging Patriarchy through Text and Form from Woolf to Cixous

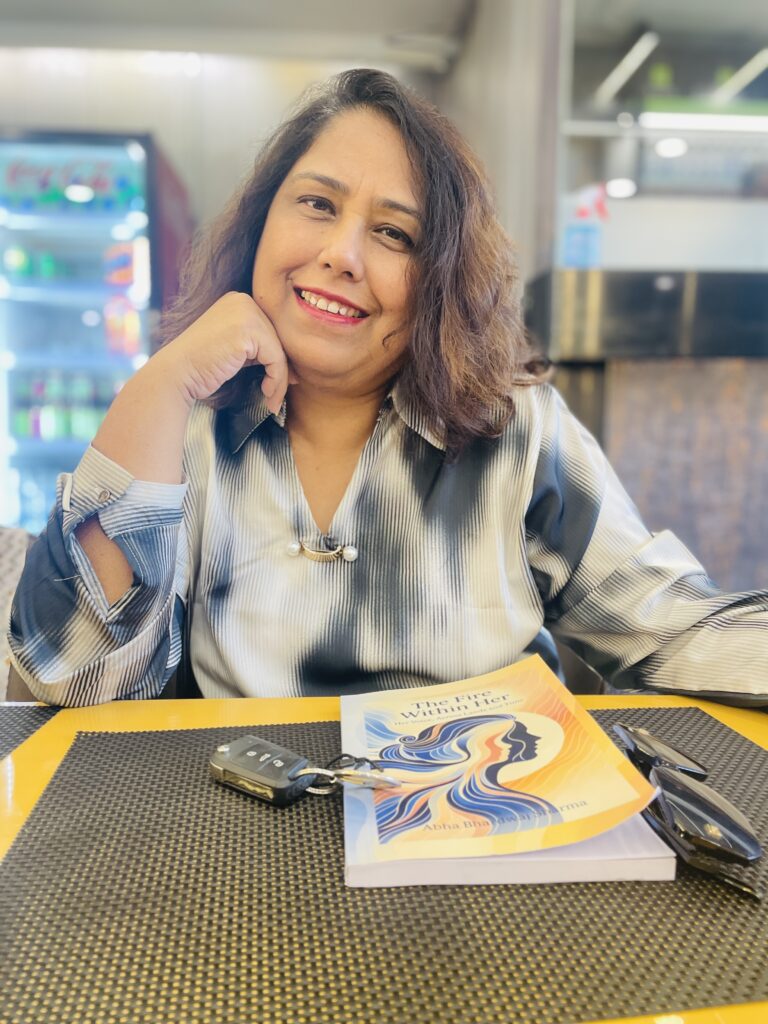

From The Professor's Desk

Opening: Feminism in Literature – A Revolutionary Voice Against Patriarchy

For centuries, literature has been largely shaped and controlled by male voices, with male authors dictating the narratives, moral values, and structures of storytelling. From Homer’s Odyssey to Shakespeare’s tragedies, to the works of Dickens, Melville, and Joyce, the literary canon has traditionally served as a mirror for patriarchal ideals, reinforcing gender roles and societal expectations. Women, in this framework, were often relegated to supporting characters, defined through the lens of male desire, ambition, and action. The world of literature was, quite simply, a male world.

Yet, as the tides of history began to shift, so too did the role of women in literature. Women started to reclaim their voices, and by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a seismic change was underway. Female writers began to assert their rightful place in the literary world, offering perspectives that had long been silenced or ignored. This shift did not happen without resistance. Early female authors often wrote within the constraints of male-dominated literary traditions, mirroring the very structures that had historically excluded them. However, by the early 20th century, the emergence of feminist thought began to catalyze a literary revolution.

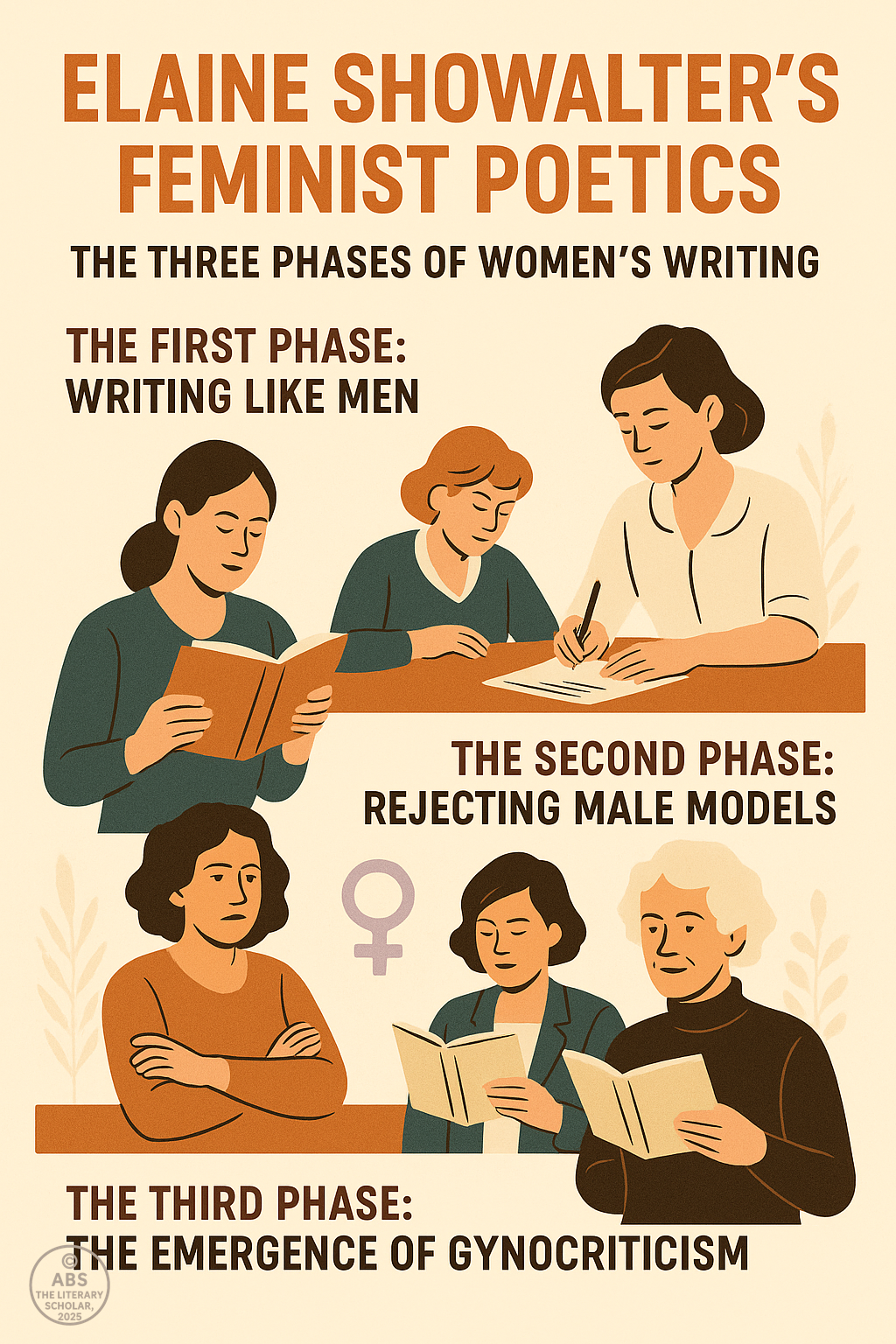

Ellen Showalter, a prominent scholar of feminist theory, coined the term “female tradition” in literature, and highlighted the distinct poetics of women’s writing. Showalter argued that for a long time, women writers had imitated male authors—either through mimicry of male narrative styles or by writing stories that adhered to male expectations of character and plot. According to Showalter, this was not a reflection of their true potential but rather the result of systematic cultural oppression. It was only when women writers realized the extent to which they had been shaped by patriarchal literary conventions that they began to rebel against them. The realization that their voices and experiences were not being represented in traditional literature led to the formation of women’s poetics—a new literary language and structure rooted in women’s experiences.

One of the most famous works that illustrated this transition was Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh (1856). A poem that boldly defied traditional female roles, Aurora Leigh chronicles the journey of a woman who is determined to live life on her own terms, carving a space for herself both in literature and in society. Through the character of Aurora, Browning gives voice to a woman’s struggle for self-empowerment and creative autonomy, marking a critical turning point in women’s literary history.

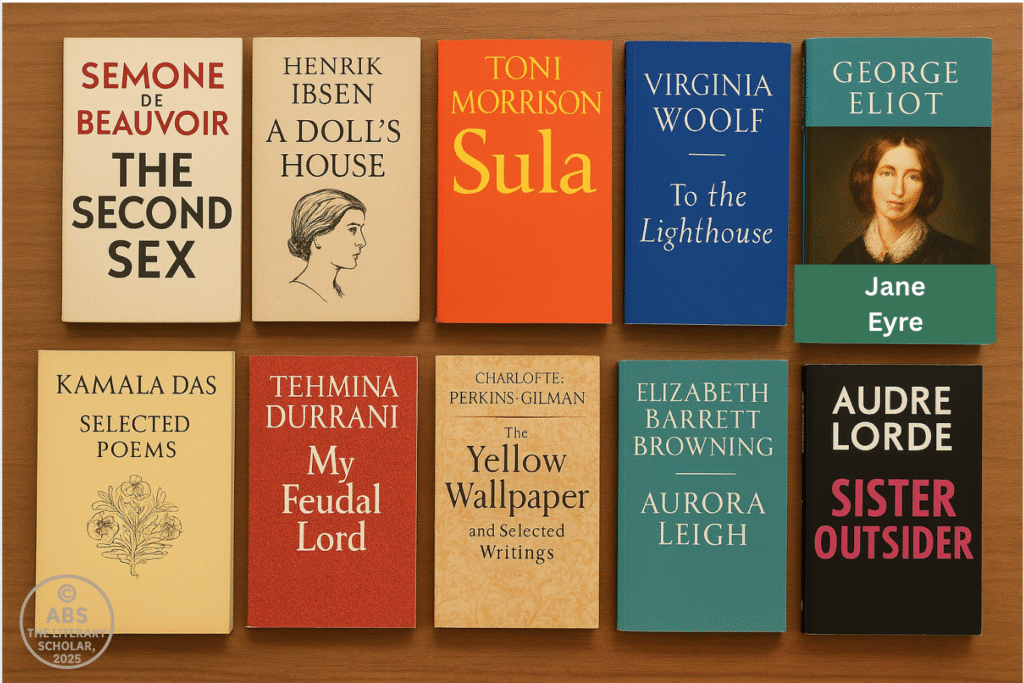

Another seminal work in the feminist literary tradition is Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (1879). Although Ibsen was a male playwright, the play’s portrayal of Nora, a woman who breaks free from the constraints of a patriarchal marriage, challenged gender norms and became a key feminist text. Nora’s decision to leave her husband and children at the end of the play symbolized women’s liberation from traditional roles, making A Doll’s House an influential work in the feminist movement and a harbinger of change in the portrayal of women in literature.

Yet, even as early feminist writers and playwrights began to challenge the structures of patriarchy, their work remained marginalized by the dominant literary traditions. It wasn’t until later, in the 20th century, that the feminist movement truly gained momentum in literary circles, fueled by thinkers like Simone de Beauvoir. In her landmark work, The Second Sex (1949), de Beauvoir explored how women had been historically constructed as the “Other”—defined in opposition to the male subject. According to de Beauvoir, women had been reduced to secondary roles in literature and society, seen only in relation to men. Her radical idea that “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman” laid the foundation for feminist literary criticism, urging women to step outside the societal confines that had long restricted them.

The feminist literary movement only grew stronger as the century progressed, with theorists like Hélène Cixous and Judith Butler continuing to challenge traditional narratives and question the very construction of gender itself. Cixous’s concept of écriture féminine—the idea of a feminine writing that rebels against the patriarchal structure of language—offered a revolutionary way of thinking about how women could write their own truths. In The Laugh of the Medusa (1975), Cixous argued that women must write in ways that disrupt male-dominated discourse, allowing for a fuller, more complex understanding of female experience.

Feminist theory also began to intersect with postcolonial theory, and writers from across the globe contributed to the growing body of feminist literature. In India, authors like Ismat Chughtai and Kamala Das explored the complexities of female identity, sexual freedom, and societal oppression. Chughtai’s short stories, such as The Quilt (1942), tackled taboo subjects like female sexuality and desire, giving voice to women’s struggles in a deeply patriarchal society. Kamala Das, in her autobiographical poems and novels, boldly confronted the cultural constraints placed on women, challenging the traditional roles of wife and mother.

In Pakistan, writers like Tehmina Durrani and Imtiaz Ahmad Dar provided a feminist critique of their societies, narrating stories of abuse, resistance, and resilience. Durrani’s memoir, My Feudal Lord (1991), recounts her tumultuous marriage to a powerful Pakistani politician and serves as a powerful statement on women’s oppression and the need for empowerment. These voices from the South Asian subcontinent not only raised awareness about the oppressive forces at work within their respective cultures but also contributed to the global feminist literary movement.

As feminist literature continued to evolve, it no longer remained confined to the Western literary tradition. Feminism began to encompass multiple voices and experiences, including those of women of color, queer women, and working-class women. The feminist writers of today are not just questioning the patriarchy but are also examining the intersections of race, class, sexuality, and gender in their works. Writers like Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, and Audre Lorde have shown how feminism can be a powerful tool for storytelling, one that encompasses the complexities of identity and history, while challenging the oppressive forces that have shaped the world.

Today, feminist literary criticism remains as vital as ever. It continues to be an essential framework for understanding the ways in which literature reflects and constructs gendered experiences. Feminist theorists, critics, and writers challenge the very foundations of traditional literary discourse, ensuring that women’s voices, bodies, and stories are no longer ignored or marginalized but celebrated and heard. From the early feminist pioneers to today’s voices of change, the struggle for gender equality in literature is far from over. The task remains to rewrite the narratives, to reclaim the body and the voice, and to empower women to tell their own stories.

1. Introduction: The Rise of Feminist Voices in Literature

For centuries, literature was shaped and controlled by male voices. From the grand epics of Homer to the tragedies of Shakespeare, from Dickens to Joyce, literature was considered a reflection of male experiences, desires, and ambitions. Female voices were either ignored or subordinated to the male narrative. Women’s roles in these works were primarily defined by the male gaze, often as passive characters in need of male protection or guidance. As a result, women’s contributions to literature were often confined to the margins, relegated to minor characters, muses, or domestic figures, their narratives largely shaped by the expectations of male authors.

This patriarchal dominance extended beyond just the themes and characters of the texts but infiltrated the very structures of storytelling. Women were not expected to be writers—their intellectual capabilities were undermined, and their voices silenced by social and cultural norms. Writing, as a form of expression, was a male-dominated space, with women’s experiences considered too narrow, too domestic, or too emotionally driven to warrant serious literary engagement. Even when women did write, they were often forced to adopt male pseudonyms or to write in ways that conformed to male expectations, mirroring male authors to gain access to the literary establishment.

However, as the women’s rights movement gained momentum in the 18th and 19th centuries, female writers began to challenge these boundaries. They emerged not to simply imitate male authors but to carve out a space for their own voices. As Mary Wollstonecraft wrote in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), “I do not wish them [women] to have power over men; but over themselves.” This was a call for women to assert their own rights and freedoms, to define themselves on their own terms, both in life and in literature. Wollstonecraft’s feminist manifesto provided the intellectual foundation for women to resist their traditional roles and demand the right to intellectual and creative freedom. It signaled a shift that would inspire generations of women to reclaim their voices and define their literary and personal identities.

By the mid-19th century, writers like Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Henrik Ibsen began to explore and expose the limitations placed on women by societal and marital structures. In her poem Aurora Leigh, Browning used the character of Aurora, a young woman who desires to be a poet in her own right, to highlight the creative struggles of women within a male-dominated literary world. “I am not a poet, but a woman who writes,” Aurora declares, signifying the tension between artistic ambition and gendered limitations. Browning’s work reflected the broader conflict women faced in asserting their literary autonomy while being confined to roles that society deemed appropriate for them.

At the same time, in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, the protagonist, Nora, takes the radical step of leaving her husband and children in order to discover herself. By rejecting the traditional role of wife and mother, Nora asserts her independence, an act that was shocking for its time but ultimately became a symbol of feminist defiance. Her decision marked the beginning of a larger cultural shift in how women viewed their roles within marriage and society.

Despite these early breakthroughs, women were still largely excluded from mainstream literary canonization. Many of these early female authors were still writing within the boundaries set by patriarchal literary traditions. They either conformed to existing forms or were forced to adopt male names or pseudonyms to ensure publication. George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans), for example, published under a male pen name to gain credibility in the literary world, a practice that was commonplace for women who wanted to be taken seriously as writers. Even as women began to assert their creative independence, the literary world still operated on masculine terms.

However, the early 20th century saw a dramatic shift. Female authors no longer felt the need to imitate male voices, but instead, they began to develop a distinct feminist literary voice that could not be defined solely by what men had written. Virginia Woolf, one of the most prominent figures in this movement, expressed the necessity for women to have their own space in which to create. In A Room of One’s Own (1929), she famously argued, “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Woolf’s assertion that women needed financial independence and intellectual freedom was revolutionary at the time. Her belief was that women’s voices could not be stifled if they had the freedom to live and write on their own terms, without being beholden to the societal and familial responsibilities that traditionally confined them.

Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949) furthered this argument by challenging the historical construction of women as the “Other”. She critiqued how women were defined in opposition to men, often treated as inferior or subservient. In her famous assertion, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” de Beauvoir turned gender from something biologically inherent into a social construct, something that society has shaped and enforced. This theory had profound implications for feminist literary criticism, encouraging critics to rethink how female characters were depicted in literature and how gender roles were embedded within literary narratives.

In the 20th century, feminist literary criticism began to gain traction, with theorists like Hélène Cixous and Judith Butler offering alternative ways to think about gender and narrative. Cixous’s concept of écriture féminine (feminine writing) argued that women must create their own language and literary forms to defy patriarchal structures that limit their self-expression. Cixous believed that women’s writing should not be constrained by male-dominated discourses, but instead should celebrate women’s unique perspectives and experiences.

Simultaneously, feminist authors like Toni Morrison began to reclaim their narratives, offering stories of empowerment that transcended traditional gender roles. In works like Sula (1973), Morrison explores themes of friendship, identity, and the complexities of race and gender. The novel’s two protagonists, Sula Peace and Nel Wright, are strong, complex women who challenge societal expectations and forge their own paths. Morrison’s work exemplifies the way feminist literature has evolved to address not just gender, but intersectional issues that affect women of different races, classes, and backgrounds.

Even in the global context, feminist literature continued to grow. In India, authors like Kamala Das and Ismat Chughtai spoke openly about the subjugation of women in their societies, addressing issues of sexuality, marriage, and domesticity. Kamala Das’s autobiography, My Story (1976), was groundbreaking in its frank discussion of her sexual desires and the societal limitations placed on her as a woman. In Pakistan, Tehmina Durrani’s My Feudal Lord (1991) told the story of her abusive marriage to a powerful politician, drawing attention to the dynamics of power and violence against women in patriarchal systems.

This global feminist wave has redefined literature as a space not just for telling women’s stories, but for challenging the structures that have long oppressed them. The role of feminist literature, now more than ever, is to disrupt traditional narratives and provide a platform for diverse female voices, allowing women to speak not just for themselves, but for other marginalized communities as well.

Today, feminist writers continue to shape the literary world, contributing unique perspectives and pushing the boundaries of what literature can represent. From intersectional feminism to eco-feminism, the landscape of feminist literature is expansive and dynamic, ensuring that women’s voices are not just heard, but celebrated, in all their complexity and diversity.

Simone de Beauvoir and The Second Sex – Foundational Feminist Theory

Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949) remains one of the most important works in feminist philosophy and literary criticism. The text provides a groundbreaking analysis of women’s historical oppression, not just in society, but in literature, culture, and the broader intellectual traditions. De Beauvoir’s work is foundational because it offers a radical shift in thinking about the gendered nature of society—one that sees women’s roles as shaped by social constructs, rather than biological determinism. Through this lens, she interrogates how women have been historically treated as the “Other”—an alien, secondary entity defined only in opposition to men.

The Notion of Women as the “Other” in Society

At the core of The Second Sex is de Beauvoir’s famous idea that women have historically been relegated to the status of the “Other”. De Beauvoir argues that men, as the dominant gender, have defined themselves as the “subject”, the primary force in society, while women have been constructed as the “Other”, the secondary, inferior counterpart. This concept challenges the traditional gender binary that has long placed men as the standard of humanity, and women as an afterthought, a reflection of the male experience. Women, de Beauvoir claims, are defined in relation to men: they are never seen as fully autonomous subjects, but always in terms of what they are not—not male, not powerful, not the default.

“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.”

— Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

This revolutionary statement captures the essence of de Beauvoir’s feminist existentialism: gender is not a natural condition, but a social construct. “Becoming” a woman is a process shaped by external forces—society, culture, and history—not an inherent aspect of a woman’s biology. According to de Beauvoir, women are taught to conform to roles imposed by society, starting from childhood, where their fate is often sealed by prescribed behaviors based on gender. Women are taught that being female is synonymous with being subordinate, leading to the creation of a social identity based on these roles rather than on an inherent sense of self.

The Impact of The Second Sex on Feminist Literary Theory

The Second Sex was a game-changer for feminist literary theory. By challenging the binary of male and female, de Beauvoir opened the door for feminist scholars and writers to reinterpret the portrayal of women in literature. Rather than accepting the traditional, passive female character in novels and plays, feminist critics began to examine how female characters were often constructed as “Other”, exoticized, or confined to stereotypical roles—such as the helpless damsel, the seductress, or the nurturing mother—all of which were designed to maintain the patriarchal order.

De Beauvoir’s ideas encouraged feminist literary critics to move beyond reading women’s oppression in literature as simply an expression of patriarchal social structures, but to also consider how literary forms themselves were shaped by gendered ideologies. For example, Virginia Woolf’s work, particularly A Room of One’s Own, became more understandable within de Beauvoir’s framework. Woolf’s exploration of women’s creative freedom and the need for economic independence was a direct response to de Beauvoir’s assertion that women must create their own existence as subjects, not as reflections of men’s desires or needs.

“The history of the oppression of women is, above all, a history of the creation of myths about women.”

— Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

This statement is a critical call to arms for feminist critics to deconstruct these myths and challenge the representation of women in literature. De Beauvoir argued that literature, like all cultural institutions, helped perpetuate these myths, making them seem natural or inevitable, rather than socially constructed. Feminist critics were tasked with uncovering the gendered subtext in classic works of literature, where female characters were often subjugated to men’s desires or reduced to supporting roles.

The Separation Between Biological Sex and Social Gender

One of the most important contributions of The Second Sex was de Beauvoir’s separation of biological sex from social gender. She argued that biological differences—the physical distinctions between male and female—do not inherently determine a person’s gender identity. Instead, gender is socially constructed, shaped by historical, cultural, and ideological forces. This concept of gender as a performance paved the way for future feminist scholars like Judith Butler, who expanded on this idea of gender performativity in the late 20th century.

De Beauvoir contended that while biological sex may determine certain physical traits, it is society that defines the roles, expectations, and behaviors that are considered appropriate for men and women. For instance, masculine traits such as assertiveness, strength, and independence are celebrated, while feminine traits like emotionality, nurturing, and passivity are devalued and confined to the domestic sphere. Women’s bodies, which are biologically female, are therefore marked as inferior in a society that privileges masculinity, making the construct of “woman” something much more than a simple biological classification.

“She is defined as the other, as the one who is not a man.”

— Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

This line reflects de Beauvoir’s core argument: women are not born with an identity imposed upon them by biology, but are instead constructed by a society that defines them in opposition to men. Feminist literary criticism was forever altered by this insight, as critics began to examine how gender roles were embodied in texts and how the social construction of gender limited the scope of women’s roles in stories, often reinforcing their marginalization in literary and social life.

De Beauvoir’s Concept of Freedom and Existentialism in Relation to Women

In addition to her critique of gender as social construct, de Beauvoir’s existential philosophy offers a framework for women’s liberation. She believed that true freedom for women could only be achieved when women could define themselves on their own terms, beyond the roles and expectations imposed upon them by society. Existentialism emphasizes individual freedom, choice, and responsibility, and de Beauvoir extended this philosophy to women’s liberation. Women’s freedom is intimately tied to their ability to make choices about their lives, bodies, and futures, not constrained by preordained roles.

De Beauvoir’s existentialist philosophy asserts that women are not defined by biology or social structures, but rather by the choices they make in the face of societal oppression. For de Beauvoir, freedom is not an abstract ideal, but a practical necessity for women to become fully human. Women must not only reject their objectified roles, but they must also seize the freedom to determine their own destiny, whether in literature, in life, or in the public sphere. This rejection of societal expectations allowed for the development of a more authentic representation of women in literature, where female characters were empowered to act, decide, and influence their own narratives.

“She will not be free until she can create herself, until she can define herself in the world.”

— Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

This call for self-definition is one of the cornerstones of feminist literary theory, as it aligns with the goal of feminist writers to not only speak for women, but also empower women to speak for themselves. Feminist authors no longer accepted the stereotypical portrayals of women in literature, but instead wrote characters who could challenge society’s restrictive notions of gender, taking control of their own destinies and finding their voices in a world that had long silenced them.

Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex continues to be a transformative work in feminist thought, offering insights that transcend literature and apply to gendered structures in all aspects of society. Her exploration of the “Otherness” of women, her rejection of biological determinism, and her existentialist conception of freedom paved the way for future feminist scholarship. The impact of The Second Sex can be seen not just in feminist literary criticism but in broader feminist movements that seek to reclaim women’s autonomy, redefine gender roles, and assert women’s agency in all walks of life. De Beauvoir’s work remains as relevant today as it was when it was first published, a crucial foundation for understanding how literature, culture, and society shape and define women—and how women can challenge and reshape those definitions themselves.

3. Virginia Woolf: The Female Modernist Voice

Virginia Woolf is a towering figure in both modernist literature and feminist thought. Her works are marked by innovative narrative techniques and a profound engagement with the female experience. Through her essays and novels, particularly A Room of One’s Own, Mrs. Dalloway, and To the Lighthouse, Woolf became not only an advocate for women’s intellectual and artistic autonomy but also a trailblazer in challenging traditional literary forms. Her contribution to feminist literature is inextricable from her exploration of the tensions between female identity, creativity, and the constraints of patriarchal society.

Woolf’s Idea of Female Creative Autonomy

One of Woolf’s most influential feminist ideas, especially in A Room of One’s Own (1929), is the belief that women’s creative autonomy is inextricably tied to their ability to have space, freedom, and resources. Woolf famously argued that to write and create, women must first have the means to do so—primarily financial independence and private space. She states:

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

This declaration was a call to arms for women to take control of their creative destinies. Woolf contended that historically, women were denied both the physical space and the financial independence needed to write, primarily because they were encumbered with the domestic duties of marriage and motherhood. Without these, women were often rendered invisible in the literary world, constrained by a society that relegated them to secondary, supportive roles.

The metaphor of the “room of one’s own” is emblematic of Woolf’s feminist philosophy. It speaks to the physical and intellectual space that women needed to nurture their creativity. In a world where the male experience was privileged, where most women were expected to care for the household, the idea of having “a room”—a private space to think, read, write, and create—was, for Woolf, a radical necessity. Women, she argued, could never truly write fiction, or produce great art, if they were constantly bound by societal constraints that stifled their intellectual and creative freedom.

The Need for Women to Have Financial Independence and Space to Write

Woolf’s argument that women need financial independence goes beyond mere practicality. It speaks to the deeper ideological implications of female autonomy. Financial independence is crucial not only for freedom but for self-respect. In her own life, Woolf had the privilege of coming from a relatively well-off family and was afforded the opportunity to pursue her intellectual interests. She recognized, however, that many women in her society did not have that privilege. For most women, economic dependence on husbands or fathers limited their freedom of expression and creativity. They were often forced to suppress their intellectual potential because their primary role was seen as domestic.

Woolf’s call for women to earn their own money was, therefore, an act of empowerment. It gave women the ability to support themselves, make their own choices, and ultimately determine their own intellectual and artistic paths. Woolf’s emphasis on money, in addition to space, was revolutionary. It recognized that women’s independence was not just about physical space but about economic and intellectual freedom. Without the means to support themselves, women were perpetually tied to the whims and expectations of others, particularly men.

In her essay, Woolf often contrasts the lives of fictional women writers—those who are stifled by financial dependence, societal expectations, and familial obligations—with the lives of men who had the liberty to write freely without these constraints. She presents the difference between the sexes not as a biological inevitability but as a result of social and economic conditions. Woolf’s message was clear: for women to have true equality in the world of literature, they must have autonomy, agency, and the means to support themselves.

Woolf’s Introspective Narrative Style

Woolf’s narrative style is often hailed as one of the most innovative contributions to modernist literature. She moved away from traditional narrative structures, opting instead for a stream-of-consciousness technique, a fragmented perspective, and an exploration of inner lives. Her novels are deeply introspective, focusing not only on external events but on the psychological states of her characters. Woolf’s writing was an attempt to capture the essence of human experience, especially the emotional and mental dimensions, which had been largely ignored in traditional, male-dominated narratives.

In novels like Mrs. Dalloway (1925), Woolf’s introspective style allows readers to engage deeply with the inner consciousness of her characters, primarily Clarissa Dalloway. Woolf’s characters often experience moments of existential reflection—moments that blur the lines between internal and external realities. In Mrs. Dalloway, the narrative flows between multiple perspectives and voices, revealing the complexities of memory, regret, and desire. Through this technique, Woolf invites readers into the thoughts and feelings of her female protagonists, showing them not as mere objects in the story but as fully realized individuals with their own inner worlds.

Similarly, in To the Lighthouse (1927), Woolf’s exploration of the interior lives of her characters—especially those of the women—creates a deep sense of emotional intimacy. The novel revolves around the Ramsay family, where Woolf gives particular attention to the inner monologues of the female characters, such as Mrs. Ramsay and her daughter Lily Briscoe. Woolf uses these characters to illustrate the tension between external expectations (particularly those related to gender and family roles) and internal desires and ambitions. The novel explores the psychological isolation that many women feel as they strive for self-actualization within a world that expects them to conform to predefined roles.

Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness style is, at its core, a radical feminist technique because it allows for the expression of women’s interiority in a way that had previously been denied. It grants women the space to express their subjective experiences—experiences that had been largely ignored or dismissed in literature up until that point.

Women’s Intellectual and Artistic Struggles Within Societal Confinement

Throughout her works, Woolf addresses the struggles women face in trying to maintain their intellectual and artistic integrity while being simultaneously confined by societal expectations. The theme of self-expression versus societal repression runs throughout much of her writing, particularly in novels like A Room of One’s Own and Mrs. Dalloway. In Mrs. Dalloway, the tension between individuality and social conformity is explored through Clarissa Dalloway’s experiences, her struggles with her own personal desires, and her dissatisfaction with the role society has assigned to her as a woman, wife, and mother.

In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf examines the historical exclusion of women from the intellectual and artistic spheres, emphasizing that women’s creativity has been stifled by societal expectations. She writes about women being educated in a way that did not allow them to cultivate their intellectual potential, and how women’s artistic expression was limited by the lack of material support—both in terms of finances and the lack of acceptance of their work in the wider literary world. Woolf’s feminist manifesto stresses the importance of literary and intellectual freedom, stating that women must have their own space, both physically and financially, to develop their creative potential without interference from the limitations of patriarchal structures.

“A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

This famous line from A Room of One’s Own encapsulates the central idea of Woolf’s feminist philosophy: female creativity is intimately linked to financial and personal autonomy. Without the material conditions that allow women to think freely, write without fear, and reject the constraints of societal expectations, they cannot hope to create art on the same level as their male counterparts.

Virginia Woolf’s contribution to feminist literature lies not just in her creative works, but in her radical rethinking of women’s roles in society and culture. Through her feminist writings, particularly A Room of One’s Own and Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf advocated for women’s intellectual freedom, autonomy, and recognition as creators in their own right. By addressing the material and emotional conditions that restricted women’s intellectual and artistic lives, Woolf’s work provided both a theoretical framework and practical guidance for feminist writers and thinkers who sought to redefine women’s roles in literature and in society. Her narrative style, with its deep psychological insights and emphasis on women’s inner lives, allowed readers to connect with her characters in profound ways, elevating women’s stories to the forefront of modernist literature. Through Woolf’s work, we see the emergence of a new literary tradition—one that is both self-aware and self-assertive in its exploration of female experience and identity.

4. Hélène Cixous and Écriture Féminine – Reclaiming Language and Writing

Hélène Cixous, a French feminist theorist and writer, made one of the most significant contributions to feminist literary theory with her concept of écriture féminine (feminine writing). In her groundbreaking essay The Laugh of the Medusa (1975), Cixous critiqued the male-dominated nature of language and literature, urging women to reclaim their voices through a distinct form of writing that defied patriarchal structures. Her theory has become an essential part of feminist discourse, providing a framework for women to reclaim language, redefine narrative forms, and express desires and experiences that were previously silenced by traditional literary conventions.

The Concept of Feminine Writing that Defies Traditional Patriarchal Structures

At the heart of Cixous’s theory is the idea that language itself is inherently patriarchal. For centuries, language—the very medium through which thoughts, ideas, and stories are communicated—has been structured around male-centered norms. The traditional structure of language has been used to define women’s roles, limit their voices, and control their representation in literature. Women, Cixous argues, have been silenced by a male-dominated linguistic system, one that excludes or distorts their experiences.

In her essay The Laugh of the Medusa, Cixous introduces the idea of écriture féminine—writing that is rooted in women’s experiences and desires, not shaped by male structures. This writing breaks away from linear, logical, and rational modes that have long dominated Western literature, instead embracing a fluid, cyclical, and organic style that better reflects the complexity of female subjectivity. In essence, écriture féminine challenges the idea that there is a single, universal way of writing. It rejects rigid, patriarchal language and offers a space for female subjectivity and expression that is not confined by male-dominated narratives.

Cixous states:

“Women must write themselves: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies…”

This quote emphasizes her rejection of male-centered language and insists that women must create their own forms of expression. It is an act of empowerment, where women are no longer passive receivers of language but become active creators of meaning.

Through écriture féminine, women can reclaim their bodies and their voices, which have historically been oppressed by patriarchal structures in both society and language. Cixous’s writing, both theoretical and creative, reflects this idea: she often uses flowing, fragmented, and poetic styles to disrupt the linearity and order that has dominated male writing. Women’s experiences, emotions, and desires—which have been historically subjugated to male perspectives—are now allowed to take center stage, expressed in ways that honor complexity and ambiguity, not clarity and certainty.

How Cixous’s Approach Challenges Male-Centered Discourse

Cixous’s theory does not simply advocate for writing from a female perspective, but for the creation of a new mode of writing that subverts male-dominated narratives. Patriarchal literature is built on structures that reinforce masculine power and control, often portraying women as secondary to male characters or limiting them to traditional roles. Through écriture féminine, Cixous calls for the deconstruction of these structures and a radical reimagining of how women’s stories can be told.

Cixous writes:

“I write this because I feel that women are not being written. They are not part of the narrative… They have been erased… This is the tragedy of women in writing, their absence, their exclusion from all the fundamental works of the world.”

This quote speaks to the historical erasure of women in literature. Women have been systematically left out of the grand narratives and, when they do appear, they are often cast in stereotypical roles—as lovers, mothers, or victims. Cixous challenges this dominant discourse by advocating for a feminine language of liberation that allows women to write their own stories and assert their own identities.

Through écriture féminine, Cixous calls on women to write themselves back into history—to become the authors of their own narratives, unbound by the constraints of traditional gender roles. This writing is not just about female experience, but about resisting the very structures that have kept women silent. It is a way to reclaim literary space and cultural influence, an act of revolutionary defiance against patriarchal norms.

Cixous’s writing is a call to arms, urging women to step into the literary world and reclaim the power of words. She rejects the idea that women must adhere to male-defined models of writing, offering instead a new language of freedom and agency. For Cixous, the act of writing is inherently political. Women’s writing is not just about self-expression, but about creating a new paradigm—one in which gender is not a limiting force, and women’s voices are at the center.

The Role of Sexuality and Desire in Women’s Writing

One of the most important aspects of Cixous’s theory is the central role that sexuality and desire play in women’s writing. Traditionally, women’s sexuality has been portrayed as something to be controlled, repressed, or viewed solely through the lens of male desire. In contrast, Cixous argues that women’s sexual and emotional experiences are essential to understanding their identity and creative expression.

Cixous writes:

“A woman who writes is a woman who is in touch with her body, who is not afraid to speak of her own desire, her own power.”

For Cixous, sexuality is not just a biological function but a site of empowerment and revolutionary potential. By embracing desire, women can reclaim ownership of their bodies and their experiences. In the traditional literary canon, women’s sexuality has often been subjugated to the male gaze, rendered as either passive or objectified. Cixous’s feminist theory turns this narrative on its head, suggesting that women’s sexuality should be celebrated and expressed freely in their writing.

Through écriture féminine, women can write their desires, allowing their bodies and their emotions to become central to their stories. This radical act of expression liberates women from the traditional roles that have restricted their sexual and emotional lives, enabling them to craft their own narratives of pleasure, identity, and empowerment. By writing about sexuality in an open, unapologetic way, women assert their right to define their own bodies, to write their desires, and to create their own sexual identities.

Cixous’s approach to sexuality in writing is liberating because it challenges the traditional repression of female desire. Women are encouraged to express not only their physical needs, but also their emotional and intellectual desires. This writing celebrates the fullness of the female experience, rejecting the idea that women should be ashamed of their desires. Instead, it invites women to celebrate their bodies, their emotions, and their sexuality as powerful forces that can shape their identity and their art.

The Legacy of Cixous’s Écriture Féminine

Cixous’s concept of écriture féminine is a revolutionary call to action for women to reclaim their voices and their stories through writing. Her theory not only challenges the dominance of patriarchal structures in literature, but also opens up new ways for women to engage with their sexuality, identity, and creative power. By rejecting the male-dominated narrative, Cixous has laid the groundwork for a new literary tradition—one where women write for themselves, not for male approval or validation. Through this writing, women can reclaim their bodies, defy oppressive norms, and create new forms of narrative that reflect their complex and varied experiences.

In conclusion, écriture féminine is not just a theoretical framework—it is an invitation for women to engage in the act of writing as a means of liberation, of reclaiming space in a world that has long denied them the opportunity to speak freely. Through Cixous’s revolutionary approach to writing, women are empowered to define themselves, express their desires, and ultimately create their own histories. Women’s voices, once marginalized and silenced, are now free to reclaim their narratives, reshaping the world of literature and beyond.

5. Gender and Identity: Judith Butler’s Performativity Theory

Judith Butler’s ideas, particularly in her seminal work Gender Trouble (1990), revolutionized feminist and queer theory by introducing the concept of gender performativity. Butler’s theory of performativity challenges the traditional binary understanding of gender and offers a way to understand gender as a fluid and socially constructed identity, rather than a biologically fixed attribute. By deconstructing the foundational assumptions about gender, Butler has had a profound influence on both feminist literature and queer theory, providing a framework for authors and critics to explore how gender identity is constructed and performed in literature and society.

Butler’s Gender Trouble and the Theory of Gender Performativity

In Gender Trouble, Butler asserts that gender is not something we are, but something we do. Rather than viewing gender as an inherent biological characteristic, Butler suggests that gender is a repeated performance—a set of actions, behaviors, and language that are culturally inscribed upon individuals. She argues that society has established rigid gender categories, typically divided into man and woman, and that these categories are reproduced through our daily behaviors. However, gender is not fixed by these performances; it is, instead, constituted through the repetitive enactment of norms.

Butler writes:

“Gender is the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame that congeal over time to produce the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being.”

Here, Butler introduces the notion that gender is not an essence but a series of performances that create the illusion of a stable identity. The idea of performing gender offers a way of understanding how individuals come to be perceived as masculine or feminine—not because of their biological sex, but because of the performance of gender norms that society expects. According to Butler, these repeated performances have the power to enforce the idea that gender is real, even though it is actually socially constructed.

Literature that Deconstructs the Binary Understanding of Gender

Butler’s theory of performativity challenges the rigid binary conception of gender, which has traditionally classified individuals into two distinct and opposing categories: male and female. Feminist and queer literary critics have drawn on Butler’s ideas to analyze how literature deconstructs this binary understanding and explores gender as a spectrum of identity and performance.

In literature, characters often embody complex, non-binary gender identities that resist traditional classifications. Works like Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (1928) and Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985) explore the fluidity of gender, showcasing characters who move between, or challenge, gendered expectations. Woolf’s Orlando, a novel in which the protagonist changes gender over the course of centuries, presents a radical blurring of gender distinctions. The novel questions the idea of a stable, essential gender identity and instead portrays gender as a performance, influenced by historical and cultural contexts. Woolf’s portrayal of gender as a mutable quality aligns with Butler’s theory of performativity and invites readers to reconsider the constraints of fixed gender roles.

Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit also challenges the binary understanding of gender, presenting a coming-of-age story about a young lesbian girl in a religious community. Winterson’s exploration of gender and sexuality reflects the tension between societal expectations of gender and the individual’s personal experience of identity. Winterson’s protagonist, Jeanette, navigates the intersection of her gender identity and sexuality, questioning and resisting the roles imposed upon her by both family and society. Winterson’s work demonstrates the fluidity of gender and the tension between individual identity and societal pressures, a theme deeply rooted in Butler’s work.

Through works like these, literature provides a space for challenging and reimagining gender. Rather than simply reinforcing binary gender norms, feminist and queer literature often engages in gender subversion, portraying characters whose gender and sexuality cannot be easily categorized. These works mirror Butler’s argument that gender is a social construction, and that the assumed naturalness of gender roles is, in fact, a repetitive performance that can be disrupted and redefined.

The Impact of Butler’s Ideas on Feminist and Queer Literary Criticism

Judith Butler’s gender performativity theory has had a profound impact on both feminist and queer literary criticism. Prior to Butler, feminist literary theory primarily focused on gender inequality and representation in literature. Critics analyzed how women were depicted, often highlighting patriarchal portrayals of women as passive, subjugated figures. Butler’s theory, however, shifted the conversation toward how gendered subjectivity is created and performed, rather than simply focusing on how gender is represented in literature.

One of the key contributions of Butler’s theory to feminist literary criticism is her challenge to the fixed categorization of women and men. Feminist critics have historically worked to identify how literature reflects or reinforces traditional gender roles, often depicting women in terms of their subordination to men. Butler’s theory of performativity, however, suggests that gender is not just a role or social position, but rather a repeated action that constructs the identity of the person performing it. This opened up new possibilities for feminist critics to think about how gender and power are produced through language and actions.

In queer literary criticism, Butler’s theory has been instrumental in challenging heteronormative assumptions about gender and sexuality. Queer theory, which emerged alongside feminist theory, examines how both gender and sexuality are socially constructed and historically situated. Butler’s work in Gender Trouble gave queer theorists the tools to analyze the ways in which gender and sexuality performativity intersect with power relations, and how literature can subvert normative understandings of both. Queer writers often focus on characters who exist outside the traditional gender and sexuality binaries, and Butler’s theory provides a framework for analyzing how these characters navigate and resist the constraints of binary gender systems.

Butler’s influence has also encouraged a more intersectional approach to feminist and queer criticism, one that examines how gender performance intersects with other systems of power, including race, class, and nationality. For instance, bell hooks, Audre Lorde, and Gloria Anzaldúa have incorporated Butler’s ideas into their own feminist and queer work, examining how gender and identity are shaped by race, class, and historical context. This intersectional perspective has deepened our understanding of how gender performativity works differently across various social contexts.

Butler’s Impact on Literary Theory

Butler’s theory has made a significant contribution to literary studies by shifting the focus from gender representation to gender construction. In literary texts, gender is no longer just a subject for discussion, but also a process that can be analyzed, deconstructed, and performed. In literary criticism, this shift has led to new ways of reading texts, emphasizing the ways in which gender is not an inherent characteristic, but something created through action, language, and repetition.

In Butler’s view, gender is performative in the sense that it is constituted by the very acts that are supposed to reflect it. Thus, in literature, characters’ gender identities are not stable but are instead constructed through their words and actions. In this light, literary texts become performative spaces where gender identity is both produced and contested. Critics working with Butler’s ideas are interested in how gender is enacted, disrupted, or subverted in texts, opening up new interpretations of characters, plots, and narrative structures.

Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity has revolutionized feminist and queer literary criticism by offering a new way to think about gender identity. Rather than being an inherent characteristic, gender is constructed through repetitive performances—a framework that allows critics to deconstruct rigid gender binaries and explore gender as a fluid, dynamic category. Through this lens, literature is a powerful site for challenging the fixed categories of male and female, offering new possibilities for understanding gender in literature and in life. As feminist and queer criticism continues to engage with Butler’s ideas, we see an ever-growing focus on how gender is enacted, resisted, and transformed in both literature and the world.

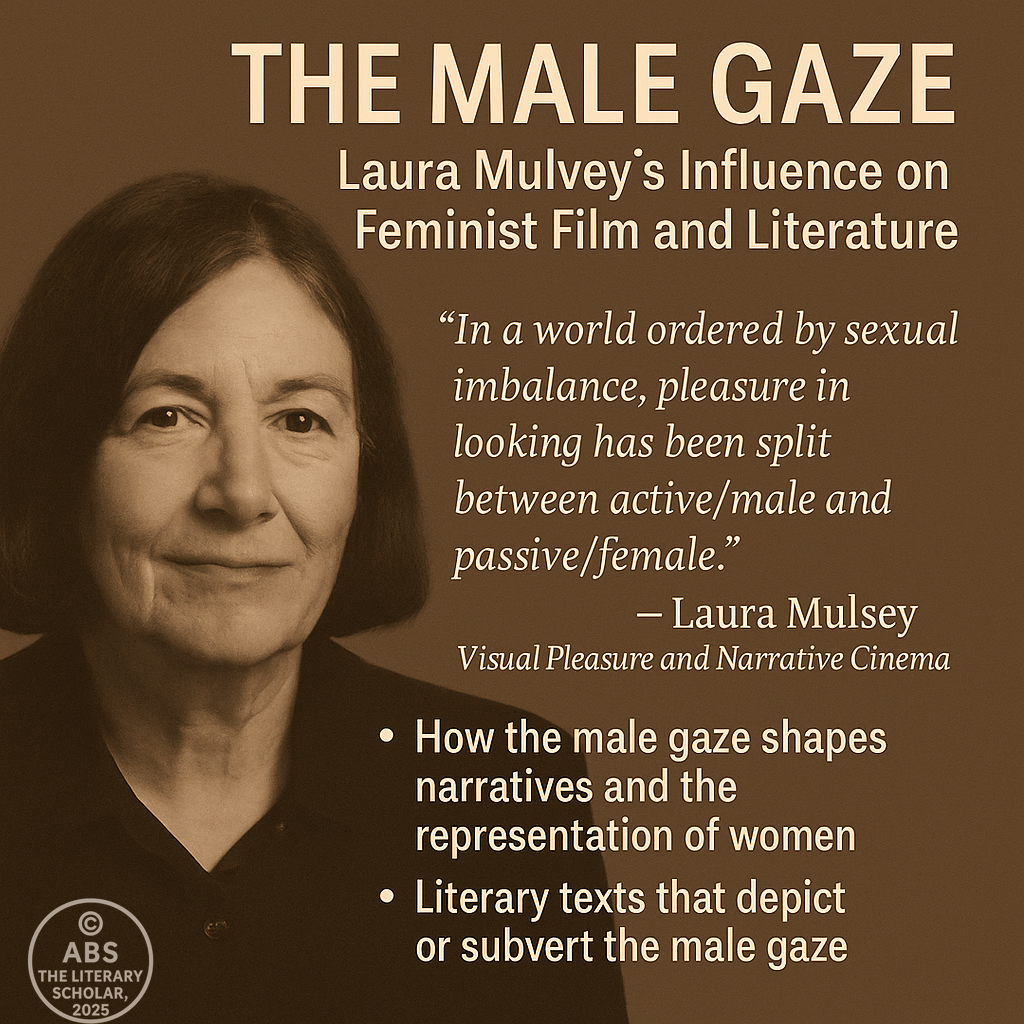

6. The Male Gaze: Laura Mulvey’s Influence on Feminist Film and Literature

In 1975, Laura Mulvey introduced the concept of the male gaze in her seminal essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Mulvey, a British feminist film theorist, argued that traditional cinema (and by extension, much of Western art and literature) is constructed around a male-centered point of view, where women are depicted primarily as objects of male desire and visual pleasure. This concept has since become foundational in both feminist film theory and feminist literary criticism, providing a framework to understand how the representation of women in media—both visual and literary—reinforces gender inequalities.

How the Male Gaze Shapes Narratives and the Representation of Women

Mulvey’s idea of the male gaze describes a dynamic where the camera or narrative point of view is controlled by the male protagonist or director, and the female characters are often reduced to passive objects to be looked at or desired. This gaze constructs women not as active agents in the narrative, but as visual objects meant for the pleasure of the male audience. According to Mulvey, the structure of mainstream cinema (and by extension, many narrative forms) places women in a secondary role, where their value is defined by their appearance, and they are often portrayed as silent, submissive, or dependent on male characters.

The male gaze is central to Mulvey’s argument about patriarchy’s influence on visual and narrative art forms. The narrative perspective of a film or novel, she suggests, often embodies the male perspective, leading to the objectification of women. In a typical narrative, the male protagonist is depicted as an active agent, whose desires and actions drive the story forward, while the female character is often positioned as a passive object of desire, whose role is to be looked at rather than to act or speak for herself.

Mulvey’s theory is rooted in psychoanalysis, particularly Freud’s concept of scopophilia (the pleasure of looking) and Lacan’s theory of the mirror stage, which suggests that the male subject sees the female object as a mirror reflection of his own desire. In cinema, this manifests through a visual code in which women are filmed in ways that emphasize their sexual appeal, their body parts, or their passivity. The woman’s body is often fragmented and presented to the audience in a way that aligns with male voyeuristic desire, turning her into an object to be gazed at rather than a subject with her own narrative agency.

“In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female.”

— Laura Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema

Literary Texts that Depict or Subvert the Male Gaze

In literature, the male gaze manifests in similar ways as in film, where women are often represented as passive objects of male desire or as mysterious, alluring figures that men must control or conquer. The male gaze in literature can also be tied to the narrative voice or the point of view from which the story is told, with male characters often serving as the narrative lens through which female characters are observed and depicted.

A classic example of literature that embodies the male gaze is Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). While the novel primarily centers around Jane’s journey to self-empowerment, much of the novel’s structure reflects the male gaze through the character of Rochester, who dominates Jane’s life in both a physical and metaphorical sense. Although Jane resists becoming a passive object of desire, Rochester’s initial treatment of her as a governess and his attempts to control her reflect a gendered dynamic of male authority over a female subject. Even the descriptions of Jane’s appearance, which are filtered through Rochester’s perceptions of her, reveal the subjugation of the female figure to the male gaze. However, Jane’s resistance to becoming a mere object of his desire marks a subversion of the male gaze, showing that she has the power to reject being reduced to an object.

Another example is Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925), where Clarissa Dalloway is seen through the lens of male characters, but Woolf subverts this perspective by focusing on the inner lives of her female characters. Clarissa, for instance, is described through the eyes of male characters, yet Woolf challenges the male gaze by emphasizing Clarissa’s internal experience and her personal autonomy. The novel works to decenter the male perspective and invest in the female subjectivity, which resists being reduced to mere visual representation.

The subversion of the male gaze can also be found in works that feature female characters who actively reject their role as passive objects of male desire. Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), a prequel to Jane Eyre, offers a critique of the male gaze by giving voice to Antoinette Cosway, a woman who is traditionally objectified and rendered mute in Jane Eyre. In Rhys’s narrative, Antoinette’s identity is shaped by her own desires, emotions, and sense of self, rather than by how she is seen by men. By giving Antoinette a voice and a backstory, Rhys subverts the traditional male gaze that objectifies women, allowing the female character to reclaim her narrative.

The Objectification of Female Characters in Classical and Modern Literature

In classical literature, the objectification of women was often tied to their depiction as the idealized woman—beautiful, passive, and in need of male protection. In Greek mythology, for instance, the figure of Penelope from The Odyssey is portrayed as the perfect wife, whose loyalty and beauty are emphasized over her agency or individuality. She is constantly observed and desired by male characters but has no agency or voice of her own. Similarly, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Ophelia’s tragic end is in part a result of her objectification by Hamlet and the court, who reduce her to a symbol of male desire and a tool in the male character’s emotional drama.

In modern literature, the objectification of female characters often appears as the sexualization of women, where female characters are frequently reduced to their physical appearance or sexuality. In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), Daisy Buchanan is portrayed as an object of desire for both Gatsby and Tom, whose worth is tied to her beauty and desirability. Her emotional life, though rich and complex, is often obscured by the male characters’ fixation on her looks and their need to possess her.

This pattern of objectification continues into contemporary literature, where female characters are often depicted as sexually objectified figures in a world dominated by male desire. In works like Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), the objectification of women is taken to its extreme, as women are reduced to their reproductive function in a dystopian society. Atwood critiques the social structures that strip women of their agency, making them mere vessels for male desires.

However, in both classic and modern literature, feminist writers have begun to challenge the male gaze by offering new representations of women—one that is more complex, active, and self-determined. Feminist literary criticism continues to push back against the objectification of women in literature and explores how gender dynamics are portrayed in narratives, offering a more inclusive and authentic representation of women’s lives.

Conclusion: Subverting the Male Gaze in Literature and Beyond

Mulvey’s concept of the male gaze has deeply influenced feminist literary criticism by providing a lens through which to analyze the representation of women in narratives. From classical literature to modern works, the male gaze has often reduced women to objects of desire, stripping them of agency and individuality. However, feminist writers and critics have worked to subvert this gaze by shifting the focus from objectification to agency, and from passivity to subjectivity. By challenging how gender and power are portrayed in literature, feminist theory continues to open up new possibilities for understanding gender dynamics, and for writing and reading literature that empowers women’s voices in ways that have been historically denied.

7. Feminist Literary Criticism Across Cultures: Global Perspectives

Feminist literary criticism has predominantly been shaped by Western traditions, but as feminist theory and literary studies have evolved, scholars have increasingly sought to explore feminist voices across cultures, particularly in postcolonial and global contexts. The incorporation of non-Western feminist perspectives into literary criticism has deepened our understanding of how gender, race, class, and colonialism intersect in shaping the lives and narratives of women. In examining feminist literature from places like India, Africa, and the Middle East, critics have revealed the diverse ways in which gender inequality and oppression manifest in different cultures, while also recognizing the unique forms of resistance and empowerment that emerge from these regions.

Feminist Voices in Literature from India, Africa, and the Middle East

India, Africa, and the Middle East have long histories of social, cultural, and political struggles that have shaped the experiences of women in these regions. Feminist literature in these areas reflects not only the gender-based inequalities women face but also how issues of race, class, religion, and colonial history complicate their lives. In these regions, feminism has often had to grapple with the intersection of traditional cultural norms, colonial legacies, and modernity.

India

In India, feminist writers have sought to deconstruct patriarchal norms deeply rooted in cultural and religious practices. Kamala Das, a pioneering Indian poet and novelist, is one of the most influential feminist voices in postcolonial Indian literature. Her work, such as My Story (1976), openly challenges traditional Indian norms regarding sexuality and female identity. Das’s autobiographical writing rejects societal repression and celebrates female desire, offering a candid exploration of her own sexuality and identity in a world dominated by patriarchal expectations. Kamala Das famously wrote:

“I am the woman who writes in the night…the night of my body’s desire.”

— Kamala Das

Through her writing, Kamala Das forces a confrontation with the ways in which Indian culture has silenced female desire and sexual autonomy. Her work calls for women to embrace their sexual identity without shame, asserting their right to sexual expression within a deeply conservative society.

Ismat Chughtai, another major figure in Indian feminist literature, similarly pushed against traditional gender roles. Her short story, The Quilt (1942), explores themes of female sexuality, desire, and the search for personal agency within the confines of a traditional, patriarchal society. Chughtai’s work challenged the moralistic attitudes towards women’s bodies and was often controversial for its depiction of female sexual autonomy. She was fearless in addressing subjects like sexuality, marriage, and female agency, marking her as an early feminist voice in Urdu literature.

Africa

African feminist literature has emerged in the context of colonialism and postcolonial struggles. Writers from across the continent have used literature to address gender inequality within a framework that also considers race, colonialism, and class. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a leading contemporary Nigerian writer, has received global acclaim for her feminist perspective in novels like Purple Hibiscus (2003) and Half of a Yellow Sun (2006). In her work, Adichie explores gender and power dynamics within the context of Nigerian society, and she often critiques the ways in which women’s roles are constrained by both patriarchal and colonial structures.

Adichie’s essay, We Should All Be Feminists (2014), is a call for a more inclusive feminism, one that understands the intersection of gender, race, and culture. Her approach to feminism is global in its scope, urging for the decolonization of feminism and acknowledging how African women must navigate both gendered oppression and the legacy of colonial rule. Adichie’s work exemplifies how gender inequality is not only a product of patriarchy but also **intertwined with the histories of race, class, and colonialism.

The Middle East

In the Middle East, feminist literature has been shaped by the tension between Islamic traditions, colonial history, and the struggles of women to define their agency within a patriarchal society. Nawal El Saadawi, an Egyptian writer, physician, and feminist, is perhaps the most well-known figure in Middle Eastern feminist literature. Her work, including The Hidden Face of Eve (1977) and Woman at Point Zero (1975), critiques patriarchal power structures and explores the ways in which religion and tradition have been used to control women’s bodies. Saadawi’s feminism intersects with Marxism and class struggle, showing how economic oppression and gender oppression are often interlinked.

Her writing is uncompromising, calling out both patriarchal religion and political regimes for their role in the subjugation of women. Her approach to feminist writing is deeply political, urging for a radical change not only in gender relations but also in the broader socio-economic structures that maintain inequality. Saadawi is a critical voice in Middle Eastern feminism, showing the intersectionality of gender and class oppression.

Intersectionality and How Race, Class, and Gender Affect Feminist Storytelling Across Cultures

Intersectionality, a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, refers to the interconnected nature of social identities—including race, class, gender, and sexuality—and how these intersections contribute to unique forms of oppression and discrimination. For feminist writers outside the Western world, intersectionality is critical because gender inequality cannot be understood in isolation; it must be analyzed in relation to colonial history, class hierarchies, and racial discrimination.

In postcolonial literature, feminist writers from India, Africa, and the Middle East have explored how colonialism and imperialism have shaped gender relations. Colonial history often led to the imposition of Western gender norms on indigenous cultures, disrupting traditional power structures and creating new forms of gender-based oppression. Colonialism and capitalism often forced women of color to navigate both the racialized oppression of colonizers and the gendered oppression imposed by patriarchal traditions within their own societies.

Feminist writers from global contexts explore how women’s stories have been shaped by these historical forces. For example, Kamala Das in India and Toni Morrison in the U.S. write about women’s struggles within cultures deeply affected by colonialism and racial segregation. They critique gender oppression while also considering how race and class play roles in shaping their characters’ experiences.

In African feminism, writers like Tsitsi Dangarembga, with works like Nervous Conditions (1988), examine the impact of colonialism and the struggles of women of color to assert their agency in both colonial and postcolonial societies. Dangarembga’s narrative is an exploration of how race, class, and gender intersect to shape women’s experiences, showing how colonialism has created complex hierarchies that women must navigate.

Conclusion: Feminist Literature Across Cultures – A Unified but Diverse Struggle

Feminist literature outside the Western tradition has played a crucial role in understanding how gender oppression intersects with race, class, colonialism, and religion. The feminist writers discussed in this section—Kamala Das, Ismat Chughtai, Tehmina Durrani, Nawal El Saadawi, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and Tsitsi Dangarembga—show that while gender inequality is a common thread across cultures, the ways in which it manifests and is resisted are shaped by unique historical, cultural, and socio-economic contexts.

Through their writing, these authors engage in a global feminist conversation, offering insights into how feminist storytelling transcends borders and engages with the complex realities of women’s lives. Intersectionality remains a crucial tool in understanding the different layers of oppression that women face around the world. Feminist literature from India, Africa, and the Middle East challenges Western narratives, offering new perspectives on gender, identity, and social justice. These voices are vital in creating a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of global feminism, highlighting the importance of recognizing how race, class, and culture influence the way gender is experienced across the world.

8. Reinterpreting Classic Texts: Feminist Critiques of the Canon

Feminist literary criticism has made a profound impact on the way we read and interpret classic texts. For centuries, literary canons have been dominated by male authors, and the stories of female characters were often told from a male perspective or placed in secondary roles. Feminist critics have revisited these canonical works, reinterpreting them through a lens that highlights the gendered power dynamics and the ways in which patriarchy has shaped both the narratives and the roles of women in these texts. This feminist approach challenges traditional interpretations, offering new perspectives on works that were often considered untouchable or beyond reproach.

Reinterpretation of Texts like Hamlet, The Odyssey, and Wuthering Heights

William Shakespeare’s Hamlet has long been hailed as one of the greatest works in Western literature, but feminist critics have pointed out how the play is deeply embedded with patriarchal values that limit the agency of female characters. The character of Ophelia, in particular, has been the subject of feminist critique. Traditionally, Ophelia is seen as a tragic figure who is defined by her relationships with the men around her—first with her father, Polonius, and later with Hamlet. Ophelia’s tragic fate, culminating in her death by drowning, is often read as a symbol of female passivity and victimhood.

However, feminist critics have reclaimed Ophelia’s story, suggesting that her madness and death can be seen as a response to her oppressive circumstances, rather than as a passive surrender to them. The feminist reading of Ophelia underscores her silence as a form of resistance—by refusing to speak and conform to the roles expected of her, she becomes a symbol of rebellion against a patriarchal system that denies her autonomy.

Similarly, in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the character of Lady Macbeth has often been viewed as the epitome of ambition and malevolence, but feminist critics have highlighted how her actions and eventual descent into madness are shaped by a patriarchal world that limits her ability to act on her desires. The character of Lady Macbeth is driven by her longing for power, but she is ultimately punished for it. Feminist interpretations of Lady Macbeth focus on how her tragic downfall is intricately linked to the constraints placed on women during Shakespeare’s time.

In Homer’s The Odyssey, female characters like Penelope and Circe have long been reduced to passive or manipulative roles, with their lives mostly centered around the male hero, Odysseus. Penelope, for instance, is often portrayed as the faithful wife, whose intelligence and cunning are overshadowed by her role as the passive object of Odysseus’s longing. Feminist readings of The Odyssey have challenged this interpretation by examining Penelope’s intellect and agency in managing the household and navigating her own desires and decisions while waiting for her husband’s return. These readings suggest that Penelope’s actions should be understood as a form of resistance to a patriarchal society that limits her choices.

In Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, the character of Catherine Earnshaw is often seen as a tragic figure whose love for Heathcliff leads to destruction. Feminist critics have interpreted Catherine’s actions as a rebellion against the roles imposed on women in Victorian society. Catherine’s wild spirit and refusal to conform to social norms challenge the expectations of women in a society that valued female domesticity and passivity. While her love for Heathcliff leads to emotional turmoil, feminist readings focus on Catherine’s agency and desire to transcend the confines of her gender and social status.

The Role of Female Characters in Classic Literature

Feminist readings of classic texts often focus on the gendered roles that women occupy in these works. In many of the canonical texts, women are often defined by their relationships to men—whether as wives, daughters, mothers, or lovers. Their agency and subjectivity are frequently subordinated to the actions and desires of the male characters. These women are passive figures who exist primarily to serve male protagonists or to serve as symbols of moral or emotional conflict.

However, feminist critics have pointed out how these women’s actions and emotions are often deeply shaped by the patriarchal world they inhabit. For example, in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, the characters of Elizabeth Bennet and Charlotte Lucas are often celebrated for their wit, intelligence, and social awareness. Yet, they are also constrained by the gender norms of Regency England, which expected women to secure their futures through marriage. Elizabeth, in particular, has been seen as a progressive character for rejecting marriage proposals that do not align with her own desires. Feminist readings of Pride and Prejudice highlight Elizabeth’s agency in making choices for herself and questioning the social norms that define women’s roles in society.

In **the works of Homer, Shakespeare, and Brontë, women characters are often subjected to the dominant male gaze, but feminist critics have pointed out how these women can resist their roles through their actions, emotions, and words. Even in works where the women are traditionally seen as tragic figures, feminist readings argue that these characters’ tragic fates are not simply a result of gender-based limitations but are indicative of how patriarchal structures shape their lives and choices. Feminist readings, therefore, give voice to the internal struggles of female characters, reading them not just as victims, but as agents of resistance in a male-dominated world.

Feminist Readings of Patriarchy, Gender Roles, and Power Dynamics in Classic Works

Feminist literary critics often analyze how gender roles are constructed and reinforced in classic works. Patriarchy in literature is often portrayed as a social system that privileges male characters and marginalizes or subjugates female characters. Feminist critics examine how these gendered power dynamics are represented in language, character relationships, and narrative structures.

In Hamlet, for example, the power dynamics between Hamlet and Ophelia reflect the gendered expectations placed on both characters. Hamlet’s rejection of Ophelia, combined with the emotional and physical abuse she suffers, highlights the ways in which women’s emotional lives are controlled and manipulated by male characters. Feminist readings of Hamlet explore how Ophelia’s madness and death are not merely the result of her unrequited love for Hamlet, but a symbol of the emotional constraints imposed on women by a patriarchal society.

In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Lady Macbeth’s ambition is presented as a threat to the established gender order. Lady Macbeth, in her desire for power, rejects traditional female roles and embraces a more masculine form of agency. Her eventual downfall can be seen as a consequence of her failure to conform to the norms of femininity—as she succumbs to guilt and madness. Feminist readings of Lady Macbeth focus on how her desires for power and her psychological unraveling reflect the gendered limitations of her time.

Similarly, in Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, the relationship between Catherine and Heathcliff is often interpreted through feminist lenses as a subversion of gender roles. Catherine’s emotional intensity and desire for freedom resist the constraints of Victorian society, which **valued female domesticity and moral virtue. Catherine’s love for Heathcliff, and her eventual demise, can be read as an expression of resistance to societal expectations, marking her as a tragic hero in the feminist tradition.

Conclusion: Reinterpreting Classic Texts through Feminist Lenses

Feminist literary critics have reinterpreted canonical texts, providing fresh perspectives on works traditionally dominated by male authors. Through their readings, they highlight the gendered power dynamics, gender roles, and patriarchal structures embedded in classic works, and they call attention to how female characters are often subjugated, objectified, or silenced by male narratives. Feminist readings give voice to these characters, revealing the complexity of their desires, struggles, and emotions, and emphasizing how these works can be subverted to reveal new insights into gender, identity, and power.

By revisiting works like Hamlet, The Odyssey, and Wuthering Heights, feminist critics have highlighted the ways in which patriarchy and gender roles are embedded in literature, offering new possibilities for understanding women’s agency in these classic texts. Through these feminist readings, canonical literature is transformed into a space for resisting traditional gender narratives, allowing readers to engage with feminist thought and rewrite the stories of women in ways that empower them rather than limiting them.

9. Feminist Writers of the 21st Century: Voices of Change

The 21st century has witnessed a flourishing of feminist voices in literature, as contemporary authors continue to challenge traditional gender norms, offering new insights into women’s roles in both society and literature. Writers like Toni Morrison, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Margaret Atwood, and Roxane Gay have made significant contributions to feminist literature, addressing issues of race, identity, and class, and expanding the possibilities of feminist storytelling. These writers not only critique existing gender structures but also embrace new forms of storytelling, including digital narratives and experimental literature, reshaping the landscape of feminist fiction in the process.

Writers like Toni Morrison, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Margaret Atwood, and Roxane Gay

Toni Morrison, widely regarded as one of the most important American writers of the 20th and 21st centuries, offered profound critiques of race, gender, and power in her works. Her novels, such as Beloved (1987) and The Bluest Eye (1970), delve into the complex intersection of black womanhood, history, and memory. Morrison’s work confronts the deep scars of slavery, racism, and gendered violence, while highlighting the resilience and agency of black women. Morrison’s writing is unapologetically empowered, offering a powerful voice to characters who reclaim their personal stories despite the forces of historical oppression.

Morrison’s work is grounded in identity and belonging but is also a radical challenge to the dominant, often whitewashed, narratives of American history. Through magical realism and lyrical prose, Morrison’s novels elevate the voices of women often left out of mainstream literature, giving them the power to define themselves outside of their oppression.