How Mikhail Bakhtin Turned the Novel into a Carnival of Clashing Truths and Talking Minds

From The Professor's Desk

When Voices Collide: The Rise of Dialogism

In the hushed intellectual corridors of early 20th-century Russia, amid the stifling airs of Stalinist ideology and the dry certainties of Formalist criticism, a quiet yet thunderous voice began to echo—one that insisted that no voice ever speaks alone. That voice belonged to Mikhail Bakhtin, philosopher, literary theorist, and reluctant revolutionary of the word.

Born in 1895, Bakhtin lived through war, exile, censorship, and silence. His writing often survived in fragments, passed hand-to-hand, buried in footnotes, and occasionally misattributed to his more politically acceptable peers. Yet despite the challenges—or perhaps because of them—Bakhtin developed one of the most radical ideas in modern literary theory: dialogism.

At a time when Formalism prized structure over soul and Structuralism sought deep, universal grammars beneath narrative, Bakhtin asked a much messier, more human question:

Can a single voice ever speak alone in literature?

For Bakhtin, the answer was a resounding no. Literature—especially the novel—is never a monologue. It is a dialogue, not just between characters, but between ideologies, classes, time periods, worldviews, and linguistic registers. Every text carries echoes of past discourses, anticipates responses, and coexists with other voices—even when trying to silence them.

This is the essence of Dialogism: the idea that meaning in literature is not authored in isolation, but constructed through interaction. A character doesn’t just speak—they answer, resist, echo, or parody someone else. And a text doesn’t just present a message—it contains many perspectives in tension, many truths jostling for space.

In contrast stands monologism—the voice that seeks to dominate, to finalize, to declare. Monologic texts present a single, authoritative worldview. Dialogic texts invite debate.

Bakhtin’s insight repositions literature not as a closed structure, but as a living conversation—messy, multi-voiced, and gloriously unresolved.

Section 1: The Polyphonic Novel: Dostoevsky and the Symphony of Voices

In the beginning, there was the narrator—and the narrator was God. At least, that’s how traditional literature treated voice: as singular, supreme, and central. But then came Mikhail Bakhtin, a Russian literary theorist who committed a small heresy: he dared to listen to the characters. And he found something startling. They weren’t merely speaking the author’s mind. They were speaking back.

Bakhtin’s theory of polyphony, introduced in Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, radically reimagines how narrative voice operates in fiction. In contrast to the monologic novel, where characters are tools to deliver the author’s ideas, Bakhtin argued that Fyodor Dostoevsky’s characters speak with autonomous ideological voices—voices that the author does not resolve or override. Each character becomes a consciousness in its own right, engaged in live, unfinalizable dialogue with others.

“In Dostoevsky, a character is not a mouthpiece. It is a soul arguing its existence in real time.”

— Interpretation of Bakhtin’s reading of Dostoevsky

Polyphony ≠ Harmony

It is tempting to think of polyphony, borrowed from musical terminology, as a form of harmony—multiple melodies blending into a pleasing whole. But Bakhtin is not writing a symphony. He’s chronicling a battle of voices. In Dostoevsky’s novels, Ivan, Alyosha, and the Grand Inquisitor don’t resolve into consensus. Raskolnikov and Sonia don’t dissolve into a unified moral vision. Instead, these conflicting truths coexist, vibrating with tension, and the reader is left to navigate the chaos.

“Polyphony in Dostoevsky is the co-existence of unmerged consciousnesses, each with its own world.”

— M.M. Bakhtin

This is literature as a philosophical boxing ring. Each character enters with their own ideology—religious, nihilistic, ethical, revolutionary—and they do not yield to the other, nor to the author.

The Puppet Show That Isn’t

In traditional realist fiction (think Tolstoy, George Eliot, Thomas Hardy), characters tend to function as extensions of a central narrative authority. They have depth, yes—but their destinies and inner lives ultimately curve toward the author’s vision. The narrator remains the moral compass. In Anna Karenina, for instance, Tolstoy subtly nudges the reader toward condemnation or pity. We are never allowed to forget who’s conducting the orchestra.

But Dostoevsky, in Bakhtin’s view, refuses this top-down moral architecture. He steps off the pedestal and lets his characters clash without resolution. There is no single worldview imposed from above; rather, we witness a novel as a living forum—a carnival of perspectives, where each voice retains its dignity and danger.

Dostoevsky vs. Tolstoy: A Study in Contrasts

This distinction is perhaps clearest when comparing Dostoevsky’s dialogic imagination with Tolstoy’s narrative omniscience.

| Feature | Dostoevsky (Dialogic) | Tolstoy (Monologic) |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative Control | Decentralized | Centralized |

| Character Autonomy | High – ideological beings | Moderate – moral exemplars |

| Conflict | Coexistence of voices | Movement toward resolution |

| Moral Authority | Reader must navigate | Narrator guides interpretation |

In Bakhtin’s universe, Dostoevsky’s genius lies not in building moral cathedrals, but in hosting cacophonous conversations without dictating who’s right.

Echoes Across Literatures: Faulkner, Morrison, Rushdie

While Bakhtin built his theory on Dostoevsky, the polyphonic spirit is not uniquely Russian. In fact, some of the greatest modern novelists have instinctively—or deliberately—followed Bakhtinian principles.

In William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, fifteen different narrators speak, including a dead woman and a child. Truth splinters. No voice wins.

In Toni Morrison’s Beloved, voices from different realms—memory, slavery, the supernatural—bleed into each other. It’s a chorus of pain, trauma, and reclamation, and Morrison allows every voice—Sethe, Denver, Beloved, Paul D—to carry narrative weight.

In Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, Saleem Sinai becomes the fractured voice of a fractured nation. Rushdie doesn’t offer neat conclusions but a mosaic of experiences, identities, and unreliable memories. Each character becomes both self and symbol, an ideological echo chamber in India’s postcolonial moment.

Why It Matters

Polyphony, then, isn’t just a literary gimmick. It’s a model for ethical reading. It teaches us that literature can be more than a story—it can be a democracy of consciousness. It warns against totalitarian interpretations. It whispers: trust no single voice. Not even the author’s.

In an age of disinformation and polarized discourse, Bakhtin’s dialogism feels prophetic. He reminds us that truth is not something handed down. It’s something struggled toward, through a multiplicity of lived experiences and contested meanings.

“The dialogic imagination lives where no voice can claim finality.”

— Summary of Bakhtin’s ethos

And in the end, perhaps that’s why Bakhtin chose Dostoevsky. Because in his novels, the questions are never fully answered. The choir never sings in unison. And no character ever speaks alone.

Section 2: “Heteroglossia: Language as a Battlefield”

Mikhail Bakhtin wasn’t just eavesdropping on literary conversations—he was tuning into a linguistic battlefield. If polyphony is about the clash of ideological voices within characters, then heteroglossia is about the clash of languages themselves. But don’t be misled by the Greek etymology (hetero = different, glōssa = tongue); this isn’t about different national languages alone. For Bakhtin, “language” meant a socio-ideological force—everyday dialects, professions, class accents, gendered phrasing, religious or scientific jargon, all jostling for dominance within a text.

“Language is not a neutral medium… it is populated—overpopulated—with the intentions of others.”

— Mikhail Bakhtin, “Discourse in the Novel”

In the eyes of traditional critics, great novels were celebrated for their “unified voice.” But Bakhtin turns this triumph upside down. He proposes that the true genius of the novel lies in its ability to hold together the discordant voices of society, without pretending they’re harmonious. In this sense, the novel becomes the most democratic of literary forms: it doesn’t erase differences—it houses them.

The Novel as a Carnival of Voices

The Novel as a Carnival of Voices

Take Charles Dickens. His novels don’t just tell stories—they parade accents, idioms, and tonal shifts across social classes. A courtly narrator might open a chapter, but before long, street slang and servant gossip flood the page. In Bleak House, Lady Dedlock speaks in polished aristocratic ennui while Jo, the street sweeper, mutters in fragmented Cockney. They inhabit the same book but never the same language-world.

George Eliot, too, plays this game but with subtle elegance. In Middlemarch, medical, religious, romantic, and political vocabularies vie for attention. Dorothea’s idealistic abstractions crash into Casaubon’s dead scholastic prose. Each speaks with linguistic sincerity—but neither has the monopoly on truth.

Then there’s James Joyce. In Ulysses, language doesn’t just refract class or region—it mutates at the cellular level. One page reads like bureaucratic minutes, the next like Latin mass, and the next like a bawdy pub anecdote. Joyce turns heteroglossia into an art form of linguistic schizophrenia—and Bakhtin would’ve cheered from the margins.

“There is no such thing as a single language… there are only speaking subjects situated in socio-ideological time.”

— Paraphrased from Bakhtin

Internal Dialogism: The Voices Inside Us

Internal Dialogism: The Voices Inside Us

Bakhtin also introduces a haunting idea—internal dialogism. Not only does a novel host many voices, but each sentence within it may carry echoes of others. A character might use a word ironically, mockingly, or as a quotation from another source—layered speech where every utterance carries historical baggage.

In The Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield’s use of phrases like “phony” or “it killed me” isn’t merely slang—it’s a critique of the adult world, a subtle rebellion embedded in teenage idiom. Similarly, in The Color Purple, Celie’s transformation in language—from fragmented, passive letters to assertive, emotionally rich speech—demonstrates a reclaiming of voice in the face of systemic silencing.

These examples show that heteroglossia isn’t chaos—it’s structured polyphony, an orchestra where dissonance is welcome and meaning is generated in tension.

Heteroglossia in Postcolonial and Feminist Texts

Heteroglossia in Postcolonial and Feminist Texts

Nowhere is heteroglossia more politically urgent than in postcolonial and feminist literature. These writers don’t just describe oppression—they undermine it linguistically.

In Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, the narrative interweaves Igbo proverbs with colonial English, producing a hybrid language that resists imperial clarity. The colonizer’s “official” language is haunted by native wisdom.

In Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, playful syntax, broken capitalization, and repurposed English reveal a childlike lens and a postcolonial struggle to make language one’s own.

Feminist reappropriations similarly challenge patriarchal discourse. Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own deliberately shifts between analytical and poetic registers, while bell hooks reclaims Black vernacular as legitimate theory. The multiplicity of language becomes a political choice—to refuse the illusion of one true voice.

“Authoritative discourse… demands our unconditional allegiance. Internally persuasive discourse is, by contrast, always contestable, always dialogized.”

— Bakhtin, again, always disrupting

Dialogism vs Monologism

Dialogism vs Monologism

The enemy of heteroglossia is monologism—that dangerous temptation of a single, unchallenged truth. Monologism seeks finality, closure, and obedience. Dialogism thrives on openness, conflict, and negotiation. It doesn’t aim to solve meaning—it aims to host it.

So when you read a novel next, ask yourself not what it says, but who’s saying it—and against whom. That, Bakhtin would argue, is where literature gets interesting. Not in agreement, but in argument.

Section 3: Carnival and the Grotesque: Subversion Through Laughter

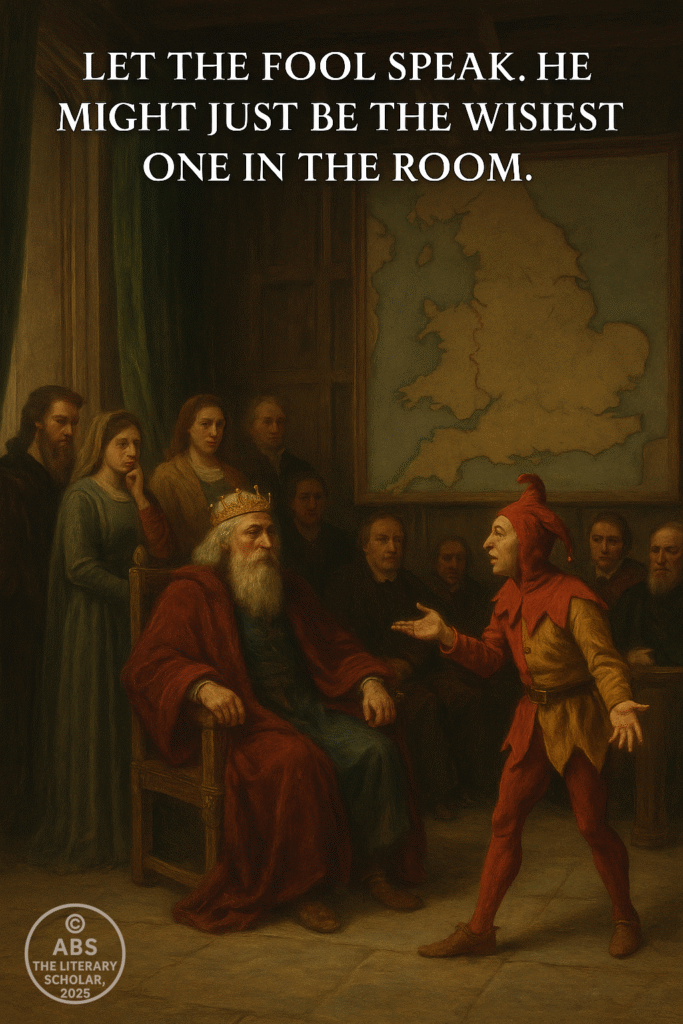

If heteroglossia showed us that language is never monolithic, then carnival proves that meaning isn’t solemn either. In Bakhtin’s iconic reading of François Rabelais, literature is not simply a polite salon of ideas—it is a festival of laughter, inversion, and deeply grotesque truths. Dialogism in literature finds one of its most explosive expressions not in philosophical discourse, but in the street theatre of carnival, where all that is sacred is profaned, all that is fixed is toppled, and the official is overwhelmed by the unofficial.

Bakhtin’s Rabelais and His World positions carnival not just as a historical celebration but as a literary mode of rebellion. Here, kings wear fool’s hats, peasants play popes, and the body—laughing, grotesque, and unashamed—reclaims the right to speak. It’s not just satire. It’s the radical democracy of the human voice in full, unedited flow.

“Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it… Carnival is the people’s second life, organized on the basis of laughter.”

— Mikhail Bakhtin

This second life breaks open the smooth surface of official discourse. Through the grotesque body—sweating, farting, eating, birthing—the text resists abstraction and embraces the physical. In dialogism in literature, this becomes a crucial counter-voice to purity, order, and discipline. The grotesque body deconstructs idealism through parody and exaggeration.

Rabelais’ characters—Gargantua and Pantagruel—aren’t symbols. They are absurd, exaggerated, and delightfully obscene. And yet, in their monstrosity lies freedom. They speak with many voices: bawdy peasant jokes, religious irony, medical curiosities, academic nonsense, and political commentary—all mashed together like a medieval stew of polyphonic subversion.

Fast-forward several centuries, and we see Bakhtin’s carnival spirit possessing the works of modern absurdists and satirists. From Swift’s fecal politics in A Modest Proposal, to Beckett’s theatrical corpse-carrying in Endgame, to Rushdie’s chutney-bottle historiography in Midnight’s Children, the carnivalesque lives on. These are texts that laugh at authority, mock reason, and remind us that even chaos deserves a mic.

“The grotesque is the expression of that which refuses to be contained.”

— Interpretation of Bakhtinian thought

Indeed, grotesque realism, as Bakhtin calls it, invites the disorderly elements of human life—birth, sex, decay, defecation—to enter the literary conversation. It’s a slap in the face of idealist literature that treats the body as shameful and the voice as pure. Dialogism in literature here becomes a carnival of competing bodies and tongues, each trying to wrestle a little space in the page’s palace.

In feminist and postcolonial circles, the carnivalesque has gained new urgency. Think of Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, where fairy tales are rewritten in blood, desire, and revolt. Or Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, where children’s language overthrows adult propriety, and metaphors leak like rain in Kerala’s monsoon. These texts dance on the border of chaos and critique, proving that laughter is not escape—it is resistance.

Carnival also invites us to reconsider the politics of genre. A novel may be dressed as high literature, but if it carries the DNA of grotesque parody or carnival laughter, it becomes subversive. Parody, satire, black comedy, farce—these aren’t just entertainment. They are polyphonic weapons against the tyranny of singular meaning.

“To write carnivalesque literature is to give voice to the silenced, the obscene, the irreverent—and to tell truth sideways, with a grin.”

— ABS, The Literary Professor

In today’s digital age, carnival hasn’t disappeared—it’s gone viral. Internet meme culture, parody videos, political satire shows, and absurdist online fiction carry the same DNA. The grotesque body may now be a TikTok filter, and the mocking fool may wear digital makeup, but the principle remains: to destabilize the official narrative with collective, creative laughter.

Bakhtin teaches us that meaning is never settled. That’s not nihilism—it’s liberation. If language is a battlefield, then laughter is its guerrilla warfare. Carnival and grotesque realism, far from being comic relief, are crucial modes of dialogism in literature—reminding us that beneath the polished prose lies a primal, pulsing, often ridiculous human truth.

Let the fool speak. He might just be the wisest one in the room.

Section 4: “Dialogism in Criticism, Culture, and the Digital Age”

If Bakhtin’s voice first echoed in literary theory, it has now become a chorus in cultural criticism and digital media. Dialogism in literature has moved beyond the pages of Dostoevsky and Rabelais—into classrooms, memes, remix videos, and even WhatsApp groups dissecting novel endings.

Dialogic Criticism vs. Authoritative Criticism

Bakhtin’s own intellectual quarrel was with monologism—not just in novels but in criticism. Traditional literary criticism often imposed a singular, “correct” interpretation, a kind of critical monarchy where the critic ruled and the text bowed in obedience. Dialogic criticism, by contrast, opens the text to conversation. It allows meanings to arise not from authority but from exchange. Each interpretation is not a final verdict but a turn in a conversation.

Critics inspired by dialogism don’t ask, “What does the author mean?” but rather, “What are the voices at play—and how do they clash or harmonize with the reader’s voice?” This shift has profoundly influenced reader-response theory, feminist literary theory, and postcolonial criticism, all of which emphasize the multivocality of experience, language, and identity.

Dialogism in the Classroom: Teaching as a Conversation

In literary pedagogy, dialogic teaching has upended the lecture-hall model where the professor’s voice was the only one heard. Instead, texts are now approached as invitation devices, encouraging students to add their own cultural, historical, and emotional voices.

A classroom discussion of Jane Eyre, for instance, no longer revolves solely around Victorian morality. One student may hear Bertha Mason’s silence as colonial suppression; another may interpret Rochester as a Byronic manipulator; a third may focus on Jane’s internal monologue as proto-feminist resistance. Each voice adds to a growing web of meanings. The teacher, in this model, becomes less an oracle and more a conductor of polyphony.

Dialogism in literature, thus, becomes a tool for intellectual democracy. And nowhere is that more visible than in today’s digital world.

Dialogism Goes Digital: Memes, Remixes, and Fan Fiction

In the age of fan fiction, BookTok, Goodreads wars, and meme culture, dialogism thrives. Multivocality is the native language of the internet. A novel’s meaning no longer ends on the last page. It spills over into review sections, video essays, Instagram reels, parody accounts, alternate endings, and cross-world fan fictions.

Take The Hunger Games. Is Katniss a rebel? A pawn? A trauma survivor? A reluctant symbol? On Reddit and Tumblr, she’s all of these—and more. In dialogic terms, this is literature refusing to be closed.

Online fan cultures are the 21st-century version of Bakhtin’s carnival—where readers, no longer silent or reverent, dress up, talk back, rewrite, subvert, and memeify every sacred narrative. A single authoritative reading dies the moment a thousand “likes” reward an alternative take.

Bakhtin’s Legacy in Cultural Theory: Kristeva, Barthes, Foucault

Bakhtin’s influence reverberates in the works of Julia Kristeva, who coined the term intertextuality—suggesting that every text is a mosaic of prior texts. Roland Barthes’s “Death of the Author” plays in the same dialogic key, insisting that the reader, not the author, completes the text. Even Michel Foucault’s analysis of power and discourse reflects dialogism’s suspicion of centralized control and univocal authority.

In essence, dialogism in literature has matured into dialogism in culture. From English classrooms to TikTok duets, from critical essays to casual tweets, we now live in a polyphonic world where meaning is negotiated, not dictated. And perhaps that’s the real victory of dialogism—not just the dethroning of the author, but the recognition that no voice ever speaks alone, and no idea escapes the echo of another.

If literature once appeared to be the sovereign voice of its author—a monologue wrapped in narrative silk—Bakhtin arrived like a quiet rebellion, whispering that every word is already a conversation. Dialogism in literature isn’t merely a method of interpretation—it is an ontological shift. It reminds us that knowledge itself is dialogic, that truth is not a single spotlight but a constellation, blinking and breathing across time and text.

In every great novel lies a polyphonic orchestra: characters who are not puppets but souls arguing their truths; narrators who are not omnipotent gods but reluctant witnesses; and languages that bleed, clash, echo, and contradict. From Dostoevsky’s mad prophets to Toni Morrison’s ghost-haunted landscapes, dialogism redefines literature as the terrain where meaning is negotiated—not declared.

The grocer’s dialect, the rebel’s slang, the colonized voice, the digital meme—each carries its own epistemology, a unique way of knowing the world. In Bakhtin’s world, even the Fool in a Shakespearean court holds court over wisdom. Every voice matters. Every utterance answers something, and anticipates a reply.

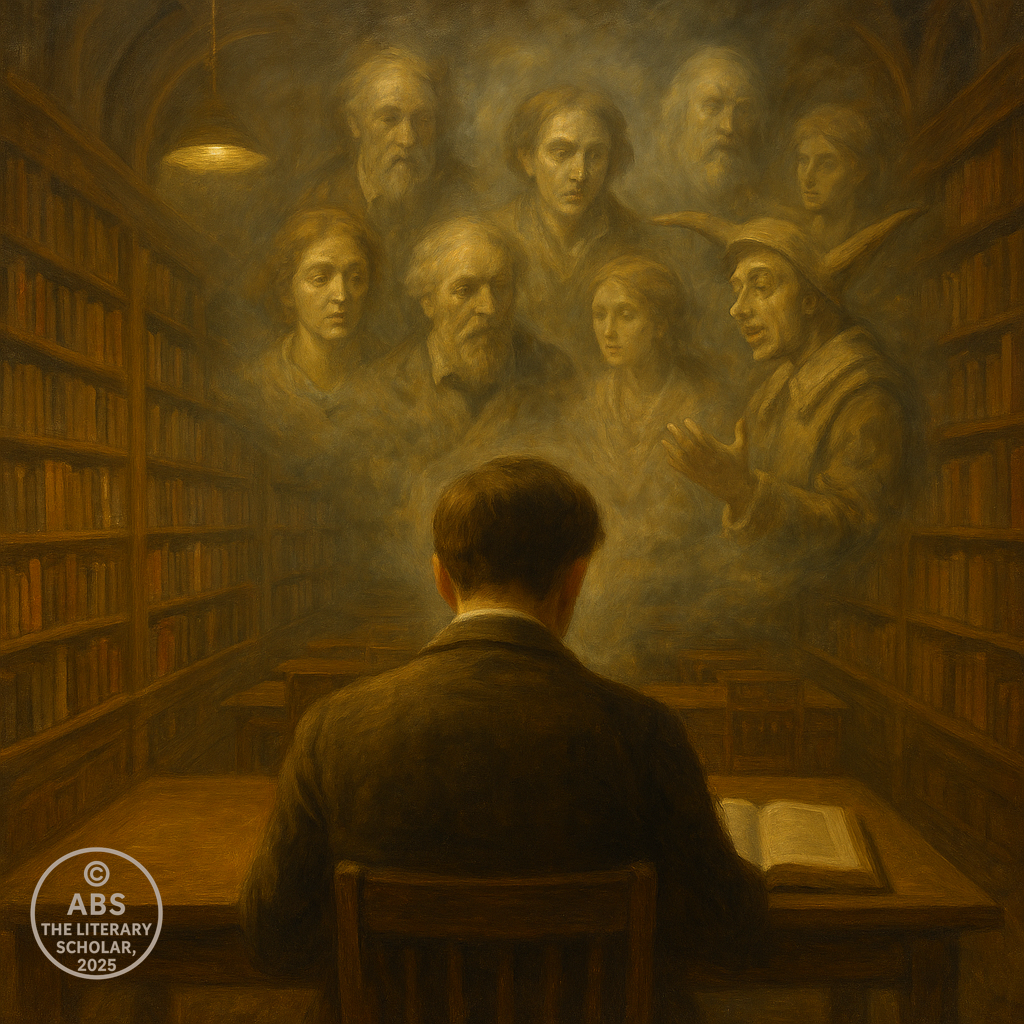

And perhaps the final image is this: a solitary reader in a vast, hushed library, eyes traveling the page, unaware that behind them stand a thousand ghosts—authors, narrators, critics, fools, lovers, gods—each one speaking, interrupting, asking to be heard. The reader turns the page. Another voice stirs.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Scholar

From the desk where voices do not end—they begin

Scroll Index: Explore Literary Theory Explained

(Click any to begin)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance

Your essay just made my graduate class finally make sense. Many, many thanks!

Thank you so much!