From The Professor's Desk

The professor often wonders why meaning, that most cherished possession of readers and critics, behaves like a well-mannered ghost: present enough to be sensed, but never quite caught in full. Literature, once thought to be the house of meaning, turns out to be haunted by absence, difference, and instability. And the theory that made this haunting visible—the one that pushed the reader from the comfort of stable interpretation into the abyss of deferred truths—is Deconstruction in Literature.

Before Deconstruction entered literary studies with its unsettling questions and unapologetic complexity, the prevailing critical traditions still held onto a secret faith: that somewhere within the text lay a center—a stable, unambiguous core of meaning waiting to be uncovered by a diligent reader. Structuralism, for all its clever scaffolding of signs and systems, still assumed a structure held together by oppositional logic and repeatable codes. It was science applied to story; clarity dressed in linguistic diagrams.

But Structuralism could not account for the slipperiness that kept creeping in. Language, after all, was never a machine. It was a trickster. Enter Poststructuralism, with its suspicion of authorial authority, its belief in the instability of signs, and its idea that meaning is always shaped by cultural, historical, and psychological contexts. Meaning wasn’t fixed—it was negotiated. Shaped in part by the reader. Twisting mid-air like a weather vane caught between winds.

Yet even this was not radical enough.

Deconstruction did not merely say that different readers interpret texts differently. It asked a more devastating question: Can a text even hold a stable meaning at all? What if the very logic of language resists closure? What if every text, at its core, is built on shifting ground, full of contradictions, tensions, and suppressed alternatives?

The professor points out: Deconstruction in literary theory is not a method; it is a revolution in reading. A refusal to play the old interpretive game. It does not seek what a text means—it exposes how the text undoes itself in the very act of trying to mean.

“The concept of centered structure is in fact the concept of a play based on a fundamental ground…” – Jacques Derrida

This is where Jacques Derrida, philosopher of the unsteady word, arrives. His 1966 lecture “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences” did not just disrupt a room full of intellectuals—it dismantled the very furniture of Western thought. What he proposed was bold: that the idea of a fixed center—whether God, Reason, Man, or Meaning—was a comforting illusion. A metaphysical security blanket passed down from Plato to Saussure.

What Derrida introduced was play—not in the childlike sense, but as a structural possibility: the play of signs, the infinite postponement of meaning, the impossibility of arriving at a final, authoritative interpretation. This wasn’t casual relativism. It was philosophical precision delivered with rhetorical elegance.

“Il n’y a pas de hors-texte.”

“There is nothing outside the text.”

This infamous phrase—often misread as literary nihilism—is better understood as a challenge: everything we understand is filtered through language, and language itself is always in motion. Words do not point directly to things. They point to other words. Meaning is not a destination—it is a detour.

Deconstruction in literary theory, then, is the art of reading for what is hidden, suppressed, silenced, or forgotten in a text. It is the effort to show that a text cannot fully say what it wants to say, because language is always echoing its own otherness. Every presence is haunted by absence. Every meaning contains its own undoing.

The professor reminds us: Deconstruction does not seek to destroy literature, but to free it—from the myth of final meaning, from the tyranny of the center, from the illusion that texts are obedient. In this scroll, we shall follow Derrida into the heart of this literary upheaval. We will examine logocentrism, binary oppositions, différance, the trace, the critique of metaphysics, and the radical shift from authorial intent to textual instability.

The journey will be rigorous. But also exhilarating. For when the center fails to hold, the margins begin to speak.

| Section | Provisional Title | Core Concept |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | “The Center Cannot Hold”: Introducing Deconstruction | Introduce Deconstruction in literary theory, focus keyphrase, Derrida’s context, how it differs from Structuralism/Poststructuralism |

| 2. | The Death of the Center: Logocentrism Exposed | What is logocentrism, Derrida’s critique, how meaning is assumed to revolve around a fixed center |

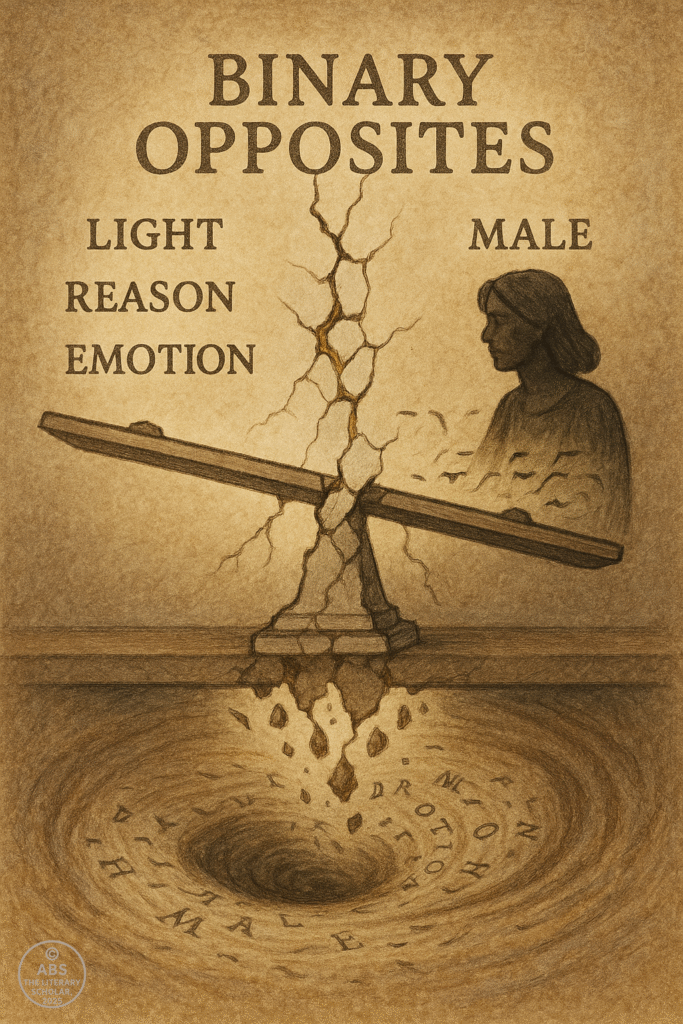

| 3. | Binary Opposites: Why Meaning Comes in Twos | Structural oppositions: good/evil, male/female; how Derrida shows they are hierarchically structured and unstable |

| 4. | Différance: Meaning on the Move | What différance is, how it delays/defers meaning, not a stable signified—origin of the term and its double play |

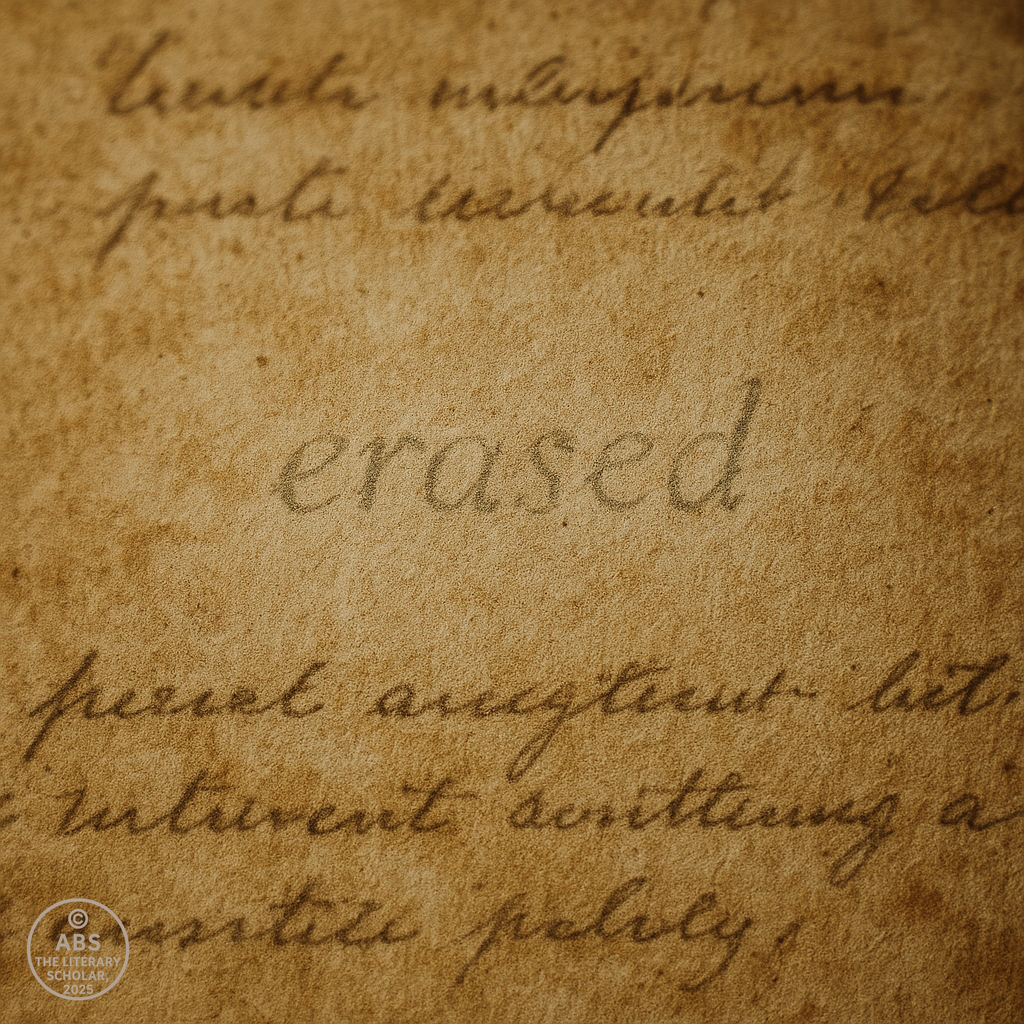

| 5. | Trace and Erasure: What’s Present Is Already Absent | The idea that what’s written carries ghost traces of what it is not—identity is built on absence |

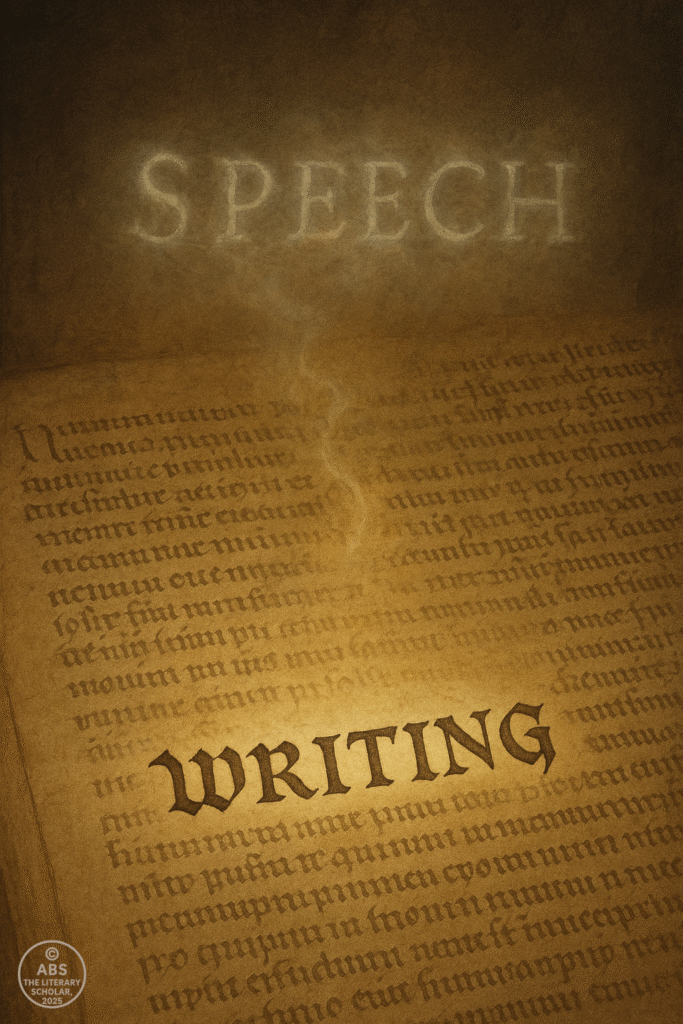

| 6. | Writing Before Speech: Derrida vs. Western Metaphysics | Why writing was always seen as secondary and how Derrida reverses the hierarchy |

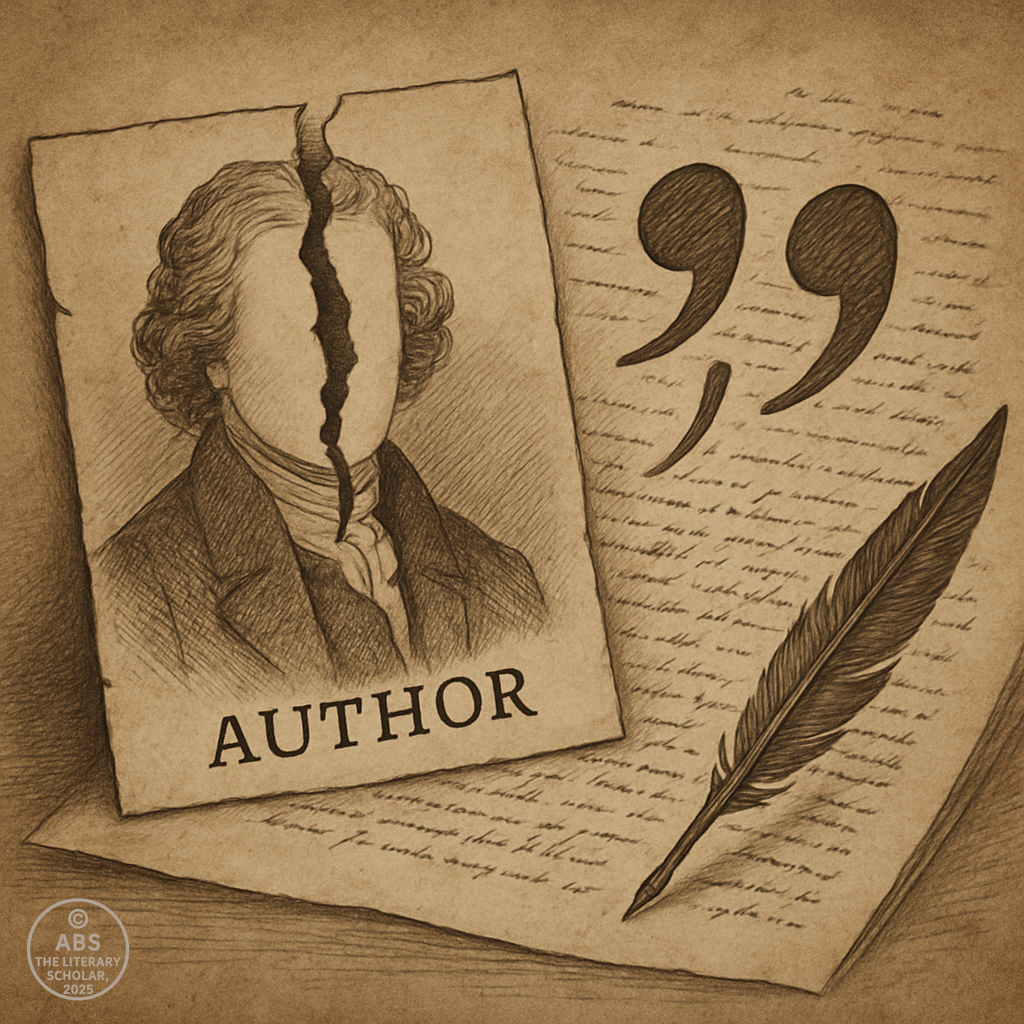

| 7. | The Fall of Authorial Intent: Who’s Speaking Anyway? | Reader vs. author; Barthes meets Derrida; “there is nothing outside the text” explained |

| 8. | Deconstruction in Action: Literary Texts Under the Knife | Deconstructive readings of canonical texts—Shakespeare, Conrad, Melville, etc. |

| 9. | Deconstruction’s Critics: Clarity, Chaos, or Cleverness? | Objections to deconstruction: Is it nihilistic? Political implications? Too obscure? |

| 10. | Post-Derrida: Echoes, Extensions, and the Unending Text | How deconstruction evolved, influenced feminism, postcolonial theory, queer theory, etc. |

The Center Cannot Hold – Introducing Deconstruction

The most dangerous reader is the one who brings a pen to the margins. Meaning was never safe. And never supposed to be.

Before the word “deconstruction” entered the literary lexicon like a rogue comma ready to unravel every sentence, the act of reading was, let’s say, more trusting. A reader once sought the author’s intent the way a devotee seeks prophecy—from the holy center of a text. Meaning was presumed stable, anchored, and obedient. The page was a container, and language, its humble servant. We decoded plots. We hunted symbols. We underlined metaphors. But we rarely asked the unnerving question: What if meaning itself is a trick?

“Deconstruction in literary theory” arises precisely at this point of discomfort—this crack in the mirror where text no longer reflects a single truth but refracts multiple, conflicting echoes. Born in the wake of Structuralism and the collapse of naïve realism, Deconstruction is less a school of thought and more an act of literary disobedience. It suspects every center. It distrusts stability. It disorients the reader on purpose.

In Structuralism, we were introduced to the delightful symmetry of signs and structures. Language became a system, a grid of oppositions. Think: male/female, light/dark, presence/absence. But the post-structuralists poked a few holes in that system and watched it leak. They showed us that meanings shift depending on the reader, the context, even the mood of the critic. And then came Jacques Derrida, with a linguistic chainsaw and a sly smile, asking not just how meaning slips, but whether it ever stood still in the first place.

“The center is not the center.” – Jacques Derrida

What Derrida proposed was simple in phrasing, but revolutionary in effect: meaning is never fully present in a text. It is always deferred, always postponed, always contaminated by what it is not. And that makes the entire enterprise of finding “what a text means” a precarious game of literary hide-and-seek. The text is not a vault of truth. It’s a maze. A glitch. A system of traces and absences, of presence haunted by everything it excludes.

Where New Critics admired the “organic unity” of a well-wrought urn, Deconstruction holds up that urn, smashes it, and says: “Ah, now we see the glue.” It does not disrespect literature; it simply stops pretending that it is innocent. It does not destroy meaning—it reveals that meaning was already collapsing, politely, in parentheses.

“There is nothing outside the text.” – Derrida again, annoyingly calm.

This statement has been misunderstood (and misquoted) more than Hamlet’s “to be or not to be.” What Derrida meant was not that reality doesn’t exist, but that our access to it is always mediated through language—language that is already slippery, unstable, riddled with assumptions, and forever divided from its origin.

And so, Deconstruction was never about dismantling books. It was about dismantling the assumptions that held books together like duct tape on a sinking ship. It peels back layers. It asks what binary oppositions a text uses—and which side it privileges. It questions the authority of beginnings, the finality of conclusions, the sincerity of claims.

Where earlier critics tried to read with the grain of the text, deconstructionists read against it—uncovering the contradictions, the undecidables, the suppressed meanings that leak through like a whispered confession. If Structuralism drew maps, Deconstruction asks whether the cartographer had an agenda.

The Death of the Center – Logocentrism Exposed

The professor has long maintained that Western philosophy suffers from a secret obsession—the need for a center. Something to hold things still. Something that does not shift while everything else moves. God, Reason, Soul, Logos, Self, Being—these have all, at different times, been assigned the privileged role of being the fixed, immovable heart of meaning. This instinct—to place something at the center in order to stabilize thought—is what Derrida famously called logocentrism.

The word may sound technical, but its effects are everywhere. In our reverence for “Truth” with a capital T. In our belief that speech is more authentic than writing. In our habit of seeking origins, foundations, and final answers. Logocentrism is not just a linguistic preference—it is a metaphysical addiction.

“The function of the center was not only to orient, balance, and organize the structure—but above all to limit the play.”

— Jacques Derrida,

To understand the violence of logocentrism, the professor insists we must first recognize its seduction. A centered structure gives us comfort. It tells us that language points to something stable. That meaning comes from a presence—something that is rather than something that differs. In this world, opposites are neatly ordered: speech over writing, male over female, reason over emotion, presence over absence, light over darkness. The structure is hierarchical, not neutral. And in each pair, one term silently dominates.

Deconstruction challenges this system not by choosing the opposite side, but by showing how the entire structure depends on exclusions—how meaning itself arises from suppressing alternatives. The center, Derrida argues, is not a neutral part of the system. It is outside the system and inside it at the same time. It organizes the rest but is not organized by it. And therein lies the philosophical scandal.

The professor often sketches it like this: imagine a circle representing language, and at its center sits “meaning.” But that center was never drawn. It was merely assumed. Deconstruction forces us to ask: what happens when the center is no longer secure? What happens when the idea of an unquestionable ground—be it God, origin, or authorial intent—is removed?

What happens, in short, when the center dies?

“What is called ‘structure’ or ‘structurality’ is always the function of a center… Yet the center is not the center.”

— Derrida, again, cracking the code

The destabilizing force that Derrida introduces is play—not frivolity, but the freedom that enters a system when the center no longer governs it. Play is what happens when meaning is not dictated but negotiated, deferred, reshaped. It is the recognition that any structure of meaning lives only by what it excludes, and that those exclusions never stay silent for long.

In literature, this has enormous consequences. The professor notes: if the center cannot hold, then the authority of the author, the fixity of theme, the certainty of closure—all fall under suspicion. A text becomes a site of tension, not resolution. It contains contradictions, excesses, echoes that cannot be tamed by a single interpretation. Deconstruction in literary theory exposes the fault lines in language itself.

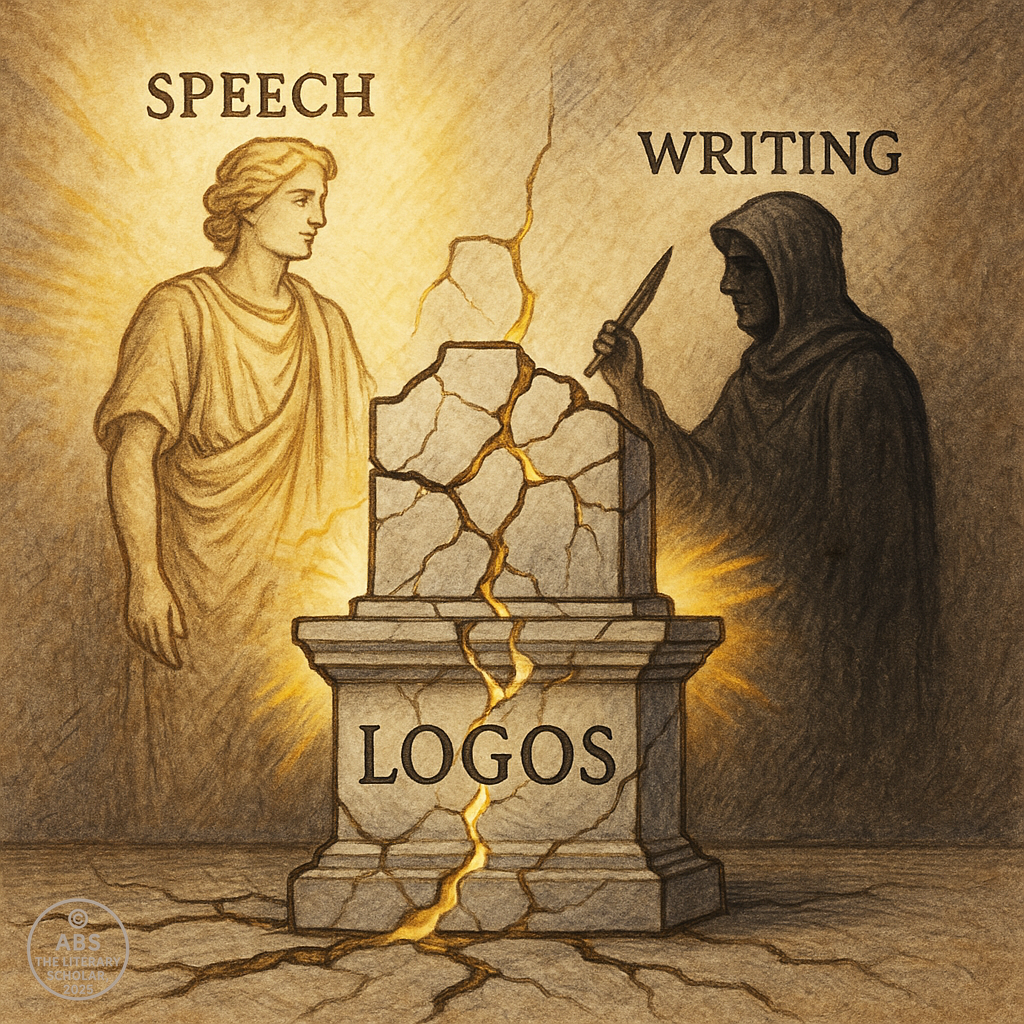

Take, for example, the privileging of speech over writing—a key target in Derrida’s Of Grammatology. Western philosophy, from Plato to Rousseau, argued that speech is natural and immediate, while writing is artificial, a mere representation of sound. But Derrida flips the binary. He shows that writing is not secondary; it is what reveals the instability of meaning. The written word is permanent, yes—but also ambiguous, unmoored from speaker and context. It can be read and misread. Repeated and reshaped. Writing, in this sense, is not a copy of speech—it is the very site where meaning unravels.

The professor reminds us that even the act of privileging one term over another—speech over writing, presence over absence—is itself a rhetorical move. A strategy, not a truth. Derrida’s brilliance lies not in denying structure, but in showing that structure always conceals a violence: the suppression of difference.

“All the names related to fundamentals, to principles, or to the center have always designated an invariable presence.”

— Jacques Derrida

Deconstruction seeks not to destroy this presence, but to trace its construction—to show how what we take as “natural” is in fact manufactured, propped up by a history of exclusions. The center doesn’t collapse by force; it implodes under the weight of its own assumptions.

And once the center gives way, a thousand other voices rise. Margins speak. Shadows stretch. Meaning flickers.

That, is where the real reading begins.

Binary Opposites – Why Meaning Comes in Twos

Every system of thought—whether linguistic, philosophical, cultural, or literary—thrives on oppositions. Light/dark, male/female, mind/body, self/other, good/evil. These binaries are not simply convenient tools for organizing the world; they are the invisible skeletons upon which centuries of meaning have been hung. From Plato to Freud, from Aristotle’s logic to Levi-Strauss’s anthropology, these paired concepts structured the way humans made sense of reality.

But what if these binaries are not innocent? What if they don’t just divide meaning, but actually distort it?

Deconstruction enters here like a forensic critic at the crime scene of meaning. It does not merely note the presence of oppositions—it exposes the hierarchies embedded within them. In nearly every binary, one term dominates, and the other is relegated to the background, marked as secondary, deviant, or derivative. In the pair speech/writing, speech has been granted presence, immediacy, and authenticity—while writing is accused of being distant, delayed, artificial. In male/female, the former is linked to activity, logic, and strength; the latter to passivity, emotion, and fragility. These are not just descriptive categories. They are loaded equations.

“To deconstruct the opposition, first of all, is to overturn the hierarchy.”

— Jacques Derrida

Derrida’s aim is not to simply flip the hierarchy (to suddenly declare writing superior to speech, or femininity above masculinity). That would still leave the binary structure intact. Instead, he reveals how the privileged term depends on the suppressed one for its very definition. Light is only light because it is not dark. Masculinity is propped up by the very image of what it excludes. Each dominant concept is haunted by the other it refuses to acknowledge.

In literature, these hierarchies manifest in both content and form. In the classical tragedy, order reigns until chaos intrudes. In colonial narratives, the colonizer defines himself through the image of the “savage.” In Victorian novels, the rational gentleman gains meaning by suppressing the unruly passions of the hysterical woman. The structure of the story—the very grammar of its worldview—relies on oppositions arranged like rungs on a ladder. But those rungs are slippery, their order always subject to collapse.

Deconstruction, therefore, is not about demolishing binaries. It’s about showing how they deconstruct themselves. The act of defining one term always leaks traces of its opposite. The line between good and evil, self and other, begins to blur the moment it is drawn.

This is nowhere more apparent than in the language of literary criticism itself. Critics speak of “form and content,” “genre and subversion,” “author and reader.” These terms too, upon closer inspection, resist clean separation. Is form not already a kind of content? Is genre not shaped by the very acts of subversion it claims to police? Are authors and readers not locked in a dance of meaning-making where each alters the other?

“A text is not a text unless it hides from the first comer, from the first glance, the law of its composition and the rules of its game.”

— Derrida, always one step ahead

Deconstruction teaches that meaning is never pure—it is always contaminated by what it is not. Every presence contains absence. Every identity carries the trace of the other. Binary oppositions, then, are not solid foundations. They are fault lines. And under the pressure of close reading, they begin to crack.

In this light, to read a text deconstructively is to interrogate its oppositions. What does the text privilege? What does it suppress? Where does it contradict itself? And where does its supposed clarity give way to ambiguity?

If literature once served to uphold certain binaries—hero/villain, order/chaos, purity/impurity—then deconstruction arrives not to burn those books, but to read them again. Closely. Suspiciously. And to listen to the whispers of what has been silenced.

Différance – Meaning on the Move

If deconstruction in literature has a heartbeat, it pulses with a strange, hybrid word: différance—a term coined, not borrowed, by Jacques Derrida. It is a word that does not exist in French speech, only in its written form, where the substitution of an a for the expected e in différence becomes not just a typographical choice, but a philosophical upheaval.

Derrida crafted différance as a challenge to how language pretends to mean. In traditional linguistics, particularly under Saussure, meaning arises through difference—a word means what it is because it is not something else. Tree means tree not because it contains “treeness,” but because it is not rock, not river, not house. Words don’t carry meaning within—they acquire it in a network of oppositions.

But Derrida adds a twist. He suggests that meaning is not only produced by difference but also by deferral. Words do not deliver their meanings immediately. They gesture outward—to other words, other contexts, future interpretations. They defer meaning as much as they define it.

“Différance is what makes the movement of signification possible only if each element that is said to be ‘present’… is related to something other than itself.”

— Jacques Derrida

In that small a, Derrida performs the very thing he’s theorizing. Spoken aloud, différance and différence are indistinguishable. But in writing, they diverge—and with that divergence comes a world of philosophical implication. Speech, long privileged in Western metaphysics for its immediacy and presence, now finds itself dethroned. Writing, that slippery archive of signs and delays, becomes the site of linguistic truth.

Différance, then, is not a word in the conventional sense. It is a conceptual device, a reminder that meaning is always already in motion. The signified is never fully present. It is always postponed, deferred, contaminated by other meanings it depends on and excludes. There is no pure point of origin—only a chain of substitutions, a play of absence, a movement that never stops moving.

“It is because of différance that the movement of signification is possible only if each element… is constituted on the basis of the trace within it of the other elements.”

— Derrida, looping meanings like lace

To read with différance in mind is to accept that literature resists finality. A novel never simply “says” something. A poem does not reveal an essence. They flicker, shimmer, tease. Meaning flickers not because the writer failed, but because language itself is structured to slip. What deconstruction in literature teaches us here is not despair, but attentiveness—an awareness that every word is haunted by others it has pushed aside, and every text carries within it the ghost of everything it is not.

This is not a call for relativism or interpretive anarchy. Derrida is not arguing that anything can mean anything. Rather, he shows that meaning emerges only through difference and deferral—a double movement that ensures every interpretation is provisional, suspended, always just one more step in the ongoing chain.

And this chain is never without tension. Because différance undermines the very logic of presence, it also destabilizes hierarchies—center/periphery, origin/copy, essence/appearance. Literary meaning, once considered a matter of arrival, becomes instead a matter of trace, of pursuit without capture. The meaning is not behind the text, nor within it, but between the lines and beyond the frame.

What makes différance so radical is that it denies the reader the luxury of resting in closure. It asks us to read not for resolution, but for reverberation. It suggests that every attempt to fix meaning only uncovers new displacements, new echoes, new aporias.

And that, ultimately, is what makes deconstruction in literature not a dead-end, but an invitation. Not a refusal to read, but a call to read differently—patiently, playfully, and without illusions of finality.

Trace and Erasure – What’s Present Is Already Absent

In the deconstructive universe, presence is never fully present. Every word we read, every concept we grasp, every meaning we extract carries the ghost of something it is not. This is what Derrida calls the trace—a silent remainder of what has been excluded, erased, or delayed in order for a particular meaning to seem whole. In truth, it never is.

Deconstruction in literature reveals that every sign contains within it the residue of all the other signs it had to push aside to appear legible. To say “light” is already to summon “dark,” to use “truth” is to invite “lie,” and to name the “self” is to imply the “other.” Meaning comes to us not as a clean arrival but as a haunted echo—structured by everything that has been repressed for it to shine.

“The trace is not a presence but the simulacrum of a presence… it inscribes in itself the reference to the other.”

— Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology

This trace is not accidental. It is not poetic mood or interpretive flourish. It is the structure of signification itself. Language works only because it never fully works—because it is always slipping, always carrying something else within it, something unspoken but not absent. A text becomes meaningful precisely because it is full of what it excludes.

To understand trace is to understand why no concept can ever stand alone. Every presence implies its own absence. Every word is built on the scaffolding of words it had to hide. And these absences—these erased possibilities—continue to operate, silently shaping what the text appears to say.

In literature, this idea is particularly powerful. Take the character who dominates a novel yet is never seen (Godot, for instance). Or the narrator who insists on truth while compulsively contradicting himself. Or the poet who builds an ode out of mourning—where loss is the very material of expression. Deconstruction in literature shows us that meaning emerges from what the text tries to bury. And the trace is the lingering pulse of that burial.

“Erasure leaves a legible mark.”

This single line, often used to capture the heart of Derrida’s thinking, reminds us that crossing something out does not make it disappear. On the contrary—it draws our eye to it. Deconstruction engages with these erasures, the crossed-out words, the silences, the shadows. It reads between the lines, not to decode a secret, but to expose the mechanics of suppression.

In this light, literature becomes a series of palimpsests—layers of meaning written over previous meanings, each trace still visible beneath the new text. And like a palimpsest, the more one scrapes to clarify, the more one uncovers what had been there all along: contradiction, hesitation, complexity.

Deconstruction in literature is not a rejection of meaning. It is a reminder that meaning is never pure. It is always contaminated by time, context, exclusion, and trace. We are never reading just the text in front of us. We are reading everything it is not saying, everything it once said and crossed out, everything it could have said but didn’t.

And so, we read with an awareness not of what is there—but of what was almost there. Of what had to be absent for the text to speak.

Writing Before Speech – Derrida vs. Western Metaphysics

In the long history of Western thought, speech was always seen as the golden child and writing as the illegitimate one. Plato distrusted writing for its permanence. Rousseau treated it as a dangerous supplement. Even Saussure, who revolutionized linguistics, bracketed writing off as merely secondary to spoken language. Speech was natural, living, present. Writing was artificial, delayed, dead.

This bias, embedded across centuries of philosophy, religion, and rhetoric, is what Derrida terms the metaphysics of presence—the privileging of immediacy, origin, and voice. It is the belief that meaning is truest when it is spoken, when it flows directly from the mouth of the subject. The written word, in contrast, was seen as suspect: a mere trace, a copy, a deviation.

But in deconstruction in literature, this hierarchy collapses. Derrida’s gesture is not simply to elevate writing but to question why speech has enjoyed such unwarranted privilege. Why do we assume that the voice carries truth more purely than the page? Why should presence be purer than absence?

“Writing is not a substitute for speech. It is not second or secondary. It is not an imitation. Writing is a condition of language itself.”

— Jacques Derrida

Derrida turns the tables. He shows that even speech is never fully present. The voice, too, operates through signifiers, through difference and deferral. It does not carry meaning straight from the soul—it moves through the same unstable structures as writing. In fact, writing simply makes the slippage visible. It exposes the delay, the deferral, the echo that was already there in speech all along.

This is why deconstruction in literature insists that writing is not derivative. It is not a shadow of something truer. It is the site where meaning reveals its instability most clearly. A word on the page does not rely on the speaker’s intent or the listener’s memory. It endures, repeats, misfires, mutates. It is free from the moment, and in that freedom, it reveals the precariousness of meaning itself.

“There is no linguistic sign before writing.”

— Derrida, overturning centuries

This does not mean writing existed before speaking in a literal sense, but that our entire understanding of signs, meaning, and difference depends on writing-like structures. Systems of signs that can be repeated, displaced, misunderstood. Speech is not immune from these conditions—it merely hides them better.

In literature, this insight is revolutionary. The written text is not a poor substitute for the author’s voice; it is the space where meaning plays, where ambiguity flourishes, where intention collapses under the weight of interpretation. A line of poetry does not whisper truth—it echoes possibilities. A novel does not recount a presence—it constructs absences, contradictions, layers.

Derrida’s reversal of the speech/writing binary is not just philosophical—it is deeply literary. For it is the written text that survives, that circulates, that refuses to be owned by its author. It is the text that outlives presence, that endures in absence, and that reminds us—every time we read—that meaning is not something we retrieve from the page, but something we chase through it.

The Fall of Authorial Intent – Who’s Speaking Anyway?

Once upon a time, the author reigned supreme. Literature was believed to be the vessel of a singular consciousness, and interpretation was a pious excavation of what the writer “really meant.” The author was the sovereign of meaning, and the critic merely a humble archaeologist brushing dust off the marble bust of intent. But in the world of deconstruction in literature, this hierarchy—like so many others—crumbles spectacularly.

The shift began with Roland Barthes and his radical pronouncement in 1967: “The author is dead.” With one stroke, Barthes challenged the entire edifice of traditional criticism. Meaning, he argued, does not reside in the author’s mind but in the interplay of the text and its reader. Once a work is written, it escapes its maker. The writer becomes irrelevant. The reader becomes sovereign.

Derrida deepened this provocation—not by assassinating the author, but by destabilizing the entire notion of a stable voice. If meaning is always deferred, always shaped by difference, trace, and absence, then no speaker, no writer, can fully control what is said. Intention becomes just one more shadow among many.

“There is nothing outside the text.”

— Jacques Derrida, provocateur par excellence

This oft-misquoted line does not mean that nothing exists outside books or that reality is a fiction. What it means is that our access to anything—reality, identity, meaning—passes through language, and language is never neutral. It is never pure. It is never innocent.

In this view, a literary work is not a message delivered from a stable sender. It is a network of signs, a site of conflict, a palimpsest of meanings that exceed and undo one another. Deconstruction in literature doesn’t ask, “What did the author intend?” but rather, “What tensions and contradictions does the text betray, despite itself?”

This is why deconstructive reading often feels like listening to a text argue with itself. A noble speech will crack under the pressure of its unspoken exclusions. A confident narrator will reveal unconscious anxieties. A coherent plot will wobble when its metaphors run wild.

Take Melville’s Bartleby, the Scrivener. The narrator insists on logic, law, and pity, but finds himself unraveling as Bartleby repeatedly utters, “I would prefer not to.” Whose voice is dominant here? The author’s? The narrator’s? Bartleby’s silence speaks more thunderously than anyone else’s logic. It is not intention that drives meaning—it is interruption.

Or consider Emily Dickinson. Her grammar defies completion, her dashes fracture thought mid-flow, her syntax loops and falters. Are we to assume a neat authorial intent behind this storm of style? Or are we witnessing language unfastened from command?

“The writer writes in a language and in a logic whose proper system, laws, and life his discourse by definition cannot dominate absolutely.”

— Derrida, Signature Event Context

In this light, even the author’s own statements—prefaces, interviews, diaries—are not keys to the text. They are texts themselves. They too are unstable, rhetorical, haunted by différance and trace. The “real” voice behind the work is never fully accessible.

Deconstruction in literature does not reduce everything to ambiguity for its own sake. Rather, it asks us to read more ethically—to resist the temptation to fix meaning, to admit the limits of certainty, to approach language as a space of multiplicity rather than authority.

The author does not disappear. But the idea of the author as meaning’s master must. What remains is not chaos, but a more honest account of how literature speaks—through layers, contradictions, and voices that do not always obey the hand that wrote them.

Deconstruction in Action – Literary Texts Under the Knife

Theory is seductive. But it is when theory meets literature that its true daring unfolds. Deconstruction in literature is not simply an abstract puzzle or a philosophical exercise—it is a radical mode of reading, a way of encountering texts that exposes how they collapse under the weight of their own ambitions. It does not aim to destroy meaning, but to show that meaning is already unraveling from within.

When applied to literature, deconstruction reads not for clarity but for cracks. It does not reduce the text to a thesis; it listens for contradictions, double meanings, silences, hesitations. The most elegant narrative, under deconstructive pressure, reveals its uneven joints. The most confident voice begins to stutter.

Take Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The play appears to hinge on questions of revenge, madness, and delay. But what if the real instability lies in the language itself? Hamlet says, “Words, words, words”—a throwaway line, until we hear it as an echo of Derrida’s insight that language cannot pin down truth. The play’s obsessive self-commentary, its doubling, its hesitations, its famous question—“To be, or not to be”—all suggest a crisis of meaning, not just of action. Hamlet does not suffer from indecision; he suffers from semiotic vertigo.

Consider Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Ostensibly a critique of imperialism, the novella is full of binaries—civilized/savage, light/dark, Europe/Africa. Yet under close reading, these oppositions dissolve. Light reveals horror, darkness becomes refuge, and the narrator Marlow ends up telling a story that contradicts its own moral tone. The text speaks against itself. Deconstruction does not accuse Conrad of hypocrisy; it shows how his language cannot uphold the binaries it relies on.

Or look at Melville’s Moby-Dick. Ahab is obsessed with a single signifier: the white whale. But the whale resists meaning. It is not a symbol—it is a blank, a void onto which everything is projected. Ahab wants it to stand for something; Ishmael swims in its ambiguity. The whale is white, pure, terrifying, unknowable. It becomes a floating différance—never fixed, never still. The novel becomes not a quest for truth but an epic of failed signification.

Even poetry, that most lyrical of forms, is fertile ground for deconstruction. In Yeats’ The Second Coming, we are told: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.” The poem yearns for meaning, for revelation, but each line deepens the disintegration. The language trembles. The poem both prophesies and panics, gesturing toward a truth it cannot fully name.

“Each text is a machine for the production of displacements.”

— Jacques Derrida

Deconstruction in literature asks: where is the tension? What does the text deny, exclude, or repress in order to seem coherent? It listens for the subtext that undoes the surface. It is not an act of cynicism—it is a practice of attention, of rigorous and sometimes irreverent listening.

A deconstructive reading does not end with a conclusion. It ends with an opening. It does not say, “Here is what the text means.” It says, “Here is how the text means—imperfectly, richly, self-contradictorily.” The aim is not to reduce literature to confusion but to reveal that literature already contains the confusion it tries to manage.

And this is why deconstruction is not an enemy of literature—it is its closest reader. It does not tear the text apart. It simply refuses to look away when the text begins to undo itself.

Deconstruction’s Critics – Clarity, Chaos, or Cleverness?

Any theory that dares to question the foundation of meaning is bound to provoke a backlash. Deconstruction in literature, with its suspicion of closure, its dismantling of binary logic, and its philosophical gymnastics, has never enjoyed quiet acceptance. If anything, it has drawn equal parts admiration and exasperation. For every critic who praises its depth and daring, another dismisses it as obscurantist, evasive, or intellectually theatrical.

Perhaps no question dogs deconstruction more persistently than this: Is it profound, or is it just clever?

To some, deconstruction feels like a trick played on interpretation—a linguistic sleight of hand that endlessly postpones understanding. Critics such as John Searle, M.H. Abrams, and even many literary traditionalists have accused Derrida of willful ambiguity, of substituting philosophical smoke for clarity, of playing games with meaning rather than engaging with it.

“With Derrida, words do not mean what they say. They do not even mean what they don’t say. They just mean less and less the more you look.”

— a familiar protest from the skeptics

One of the primary accusations leveled against deconstruction is that it breeds relativism—the idea that if meaning is always deferred, if every text undermines itself, then no interpretation is better than another. It is the anxiety of a critical free-fall: without stable meanings, how can we say anything at all? Doesn’t deconstruction risk turning literary criticism into an unanchored drift of “readings” with no ground beneath them?

Derrida himself was keenly aware of this charge. He insisted that deconstruction is not nihilism. It does not deny meaning. It complicates the process by which meaning comes to be. And that complication, he argued, is ethical. It forces us to reckon with what is repressed, silenced, or excluded in any system of thought. Deconstruction doesn’t say “nothing is true.” It says, “every truth carries the trace of what it had to silence.”

“Deconstruction is not destruction.”

— Jacques Derrida

Another criticism concerns accessibility. Derrida’s writing is famously dense, elliptical, and full of rhetorical loops that frustrate even patient readers. Terms like différance, trace, supplement, and logocentrism come wrapped in layers of theoretical nuance. Even sympathetic readers have sometimes asked whether deconstruction’s style is needlessly arcane, more performance than proposition.

Yet this, too, is part of the point. If language itself is unstable, Derrida argues, then no philosophy that deals with language should pretend to be transparent or easy. The difficulty is not a mask—it’s a mirror. Deconstruction performs the very instability it describes. The form mimics the content. The prose wavers because the meaning does too.

In literature departments, deconstruction has also been criticized for turning readers into demolition experts—tearing down texts instead of engaging with their beauty, emotion, or historical context. There is a fear that close reading becomes cold reading: joyless, skeptical, overly cerebral. Where is the music, the affect, the imagination?

But here again, the opposition is too neat. Deconstruction is not a refusal to feel. It is a refusal to simplify. It listens not only to what the text sings, but to the notes it didn’t hit, the harmony it abandoned. It brings a slow, patient attention to the mechanics of meaning, an attention that is not devoid of love—it is, in fact, a deeper form of care.

Still, not all objections can be swept aside. Deconstruction can be overused, mimicked poorly, or weaponized for vagueness. Not every cryptic essay is deconstructive. Not every contradiction is profound. And Derrida himself never intended deconstruction to become a fashionable pose or a literary party trick.

What remains is a method—and more than that, a stance toward language—that continues to challenge the way we read, write, and think. Whether one sees it as chaos or clarity may depend less on Derrida and more on the reader’s own need for closure. Deconstruction in literature is not interested in giving you peace. It wants to give you precision through instability.

Because sometimes, it’s not what a text means. It’s how it means too much to hold in place.

Post-Derrida – Echoes, Extensions, and the Unending Text

If Jacques Derrida cracked open the foundations of Western thought, what followed was less a reconstruction and more a radiation—a dispersal of his ideas into fields far beyond philosophy or literary studies. Deconstruction in literature did not end with Derrida; it multiplied, mutated, and merged with voices and movements that carried its spirit into new terrains. The text, as Derrida might say, had already begun to write itself elsewhere.

Deconstruction’s legacy is not a school but a pulse, felt in feminist theory, postcolonial studies, queer criticism, cultural analysis, and even architecture. Wherever binaries are questioned, wherever margins are made to speak, wherever certainty collapses into layered complexity—there, deconstruction breathes.

In feminist theory, deconstruction provided the tools to interrogate entrenched gender binaries. Thinkers like Hélène Cixous and Luce Irigaray used Derridean strategies to expose how language privileges masculinity, how “woman” exists as a supplement, a trace, within phallogocentric discourse. Cixous’s écriture féminine does not reject language—it rewrites it from within, bending it toward the body, the unsaid, the silenced.

“Woman must write herself: must write about women and bring women to writing…”

— Hélène Cixous

In postcolonial theory, deconstruction’s skepticism of “centered” narratives helped expose the mythologies of empire. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, who translated and interpreted Derrida’s work for the Anglophone world, famously asked: Can the subaltern speak? Her deconstructive answer was not a simple yes or no—it was a meditation on how speaking is always already framed, interrupted, overwritten.

The colonial project was full of binaries: civilized/savage, modern/primitive, West/Other. Deconstruction exposed not only how these binaries were constructed but how they relied on the suppression of difference to function. In this way, deconstruction became a method of resistance.

In queer theory, Derrida’s logic of the trace and différance found new resonance. Judith Butler, in Gender Trouble, showed how gender is performative, not natural—a repeated script, not a stable identity. The binary of male/female, like all others, wobbles under pressure. Gender is not expressed—it is citational, an echo of echoes, without an origin.

“There is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very ‘expressions’ that are said to be its results.”

— Judith Butler

Even in theology and ethics, deconstruction has left its mark. John D. Caputo and others in “radical theology” read Derrida’s specters and aporias not as obstacles to belief, but as invitations to think the sacred beyond certainty. Deconstruction in literature thus becomes deconstruction in faith, deconstruction in ethics—a commitment to the Other, to the undecidable, to the call that cannot be pinned down.

And yet, through all these extensions, Derrida’s own insistence remains: Deconstruction is not a technique. It is not a doctrine. It is an event. It happens within the text. It is what the text does to itself. The reader doesn’t impose deconstruction—the text invites it.

This is why Derrida resisted systematization. He never offered a method, a how-to guide, a checklist. Because to do so would be to center what must remain unsettled. Deconstruction is a practice of receptivity, of listening carefully, ethically, to the tremors in meaning.

Today, the term “deconstruction” has been widely misused—tossed casually in fashion, journalism, even cuisine. But in literature, its core remains intact. It continues to shape how we read, how we teach, how we speak about meaning itself. It reminds us that texts are not mirrors—they are kaleidoscopes. They do not reflect the world as it is. They refract it—fractured, plural, unfinished.

“A text is never simply itself.”

— Derrida, always with a whisper

To read deconstructively is not to give up on meaning—it is to read with awareness, with caution, with an ear to the whispering margins. It is to admit that even the most confident line of prose carries a nervous tremor beneath its surface.

And so the scroll ends. But not with a period.

ABS, the Literary Professor, places the final page gently atop the others—aware that the text, like thought, never truly concludes.

Because deconstruction never says “The End.” It only says, “To be read again.”

Scroll Index: Explore Literary Theory Explained

(Click any to begin)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance