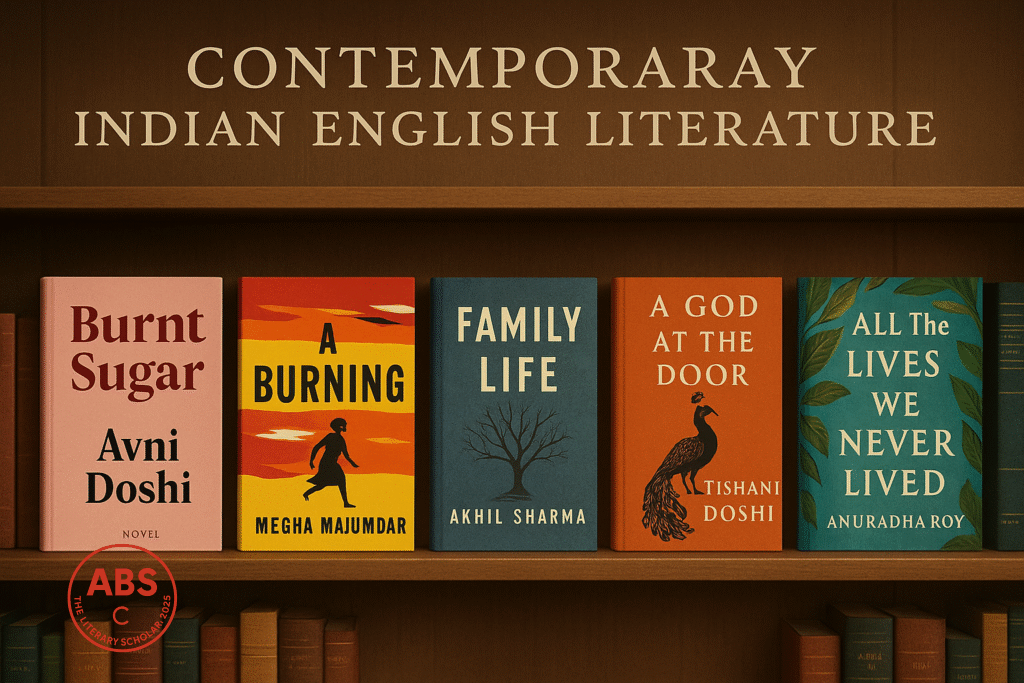

Avni Doshi, Megha Majumdar, Akhil Sharma, Tishani Doshi & the writers who made Indian fiction sharper, darker, and globally relevant again

By ABS, The Literary Scholar, who believes that emotional damage, when processed properly, becomes literary acclaim.

Literature evolves like fashion. One day you’re wrapped in epic metaphors and Gitanjali gloom, the next you’re writing about climate change, dead fathers, and why your mother doesn’t love you—in prose so sparse, it needs a sweater.

Welcome to Indian English Literature, Version 6.0. This is the age of emotional austerity, political urgency, and minimalist trauma. The writing is colder, sharper, and dressed in clean-cut sentences—but beneath the restraint lies an unapologetic fire.

This scroll is for those who came after Rushdie’s word-flood and Roy’s river of ache. These are the writers who grew up amidst page-turners, post-truths, and password-protected identities. They’ve inherited India—but with a filter, a question mark, and a tendency to ghost old tropes.

Avni Doshi: When Memory and Motherhood Become a Psychological Crime Scene

Let’s begin with the novel that should have come with a trigger warning for anyone with a complicated mother.

Avni Doshi’s Burnt Sugar (2020)—shortlisted for the Booker—is the literary equivalent of sitting in therapy for three hours, only to be told you’re still wrong.

“I would be lying if I said my mother’s misery has never given me pleasure.”

The sentence slaps. And so does the novel.

Set in Pune, the story follows Antara and her fading, toxic mother—Tara. What begins as a tale of dementia quickly unravels into a deeper wound: intergenerational resentment, failed art, broken memory, and the subtle violence of neglect.

Doshi’s prose is lean, precise, and psychologically surgical. It doesn’t ask for empathy. It demands honesty. Burnt Sugar is not here to charm you—it’s here to peel you.

It’s about motherhood, yes—but not the one with lullabies. It’s about the kind where love feels like obligation and intimacy tastes like ash.

Megha Majumdar: When Politics Becomes Thriller and Dystopia is Local News

If Doshi makes memory brutal, Megha Majumdar makes democracy a ticking time bomb.

A Burning (2020) is set in a version of India that feels disturbingly familiar. A Muslim girl is arrested after a Facebook post. A gym instructor becomes a political pawn. An aspiring actress sells more than just dreams.

“If the police didn’t stop the fire, maybe it means it’s okay.”

It’s fast. It’s tight. It’s terrifying.

Majumdar’s genius lies in how she takes India’s political disarray and pours it into a story that reads like a thriller, but leaves the aftertaste of helplessness. There are no heroes. Just ambition, propaganda, algorithms, and the terrifying silence of the masses.

She wrote this while working full-time in publishing. So yes, she’s brilliant—and yes, she’s also probably not sleeping.

A Burning is not about one injustice—it’s about how systems chew you alive, and how “going viral” might be the last thing you ever do.

Akhil Sharma: Autobiography That Hurts Because It’s True

Where Majumdar stabs you with pace, Akhil Sharma slices you slowly with stillness.

His novel Family Life (2014) is a semi-autobiographical account of migration, family breakdown, and the quiet cruelty of Indian immigrant households where success is survival—and emotion is optional.

“We had come to America for a better life, but I could not see what was better about it.”

The novel begins with a tragic swimming pool accident that leaves his brother brain-damaged. What follows is not melodrama, but meticulous ache. The prose is so understated, you barely notice the heartbreak until it floods your chest.

Sharma’s strength lies in what he doesn’t say. His language is stripped bare—like the walls of a family home that once held dreams but now holds resentment and a hospital bed.

His first novel, An Obedient Father (2000), was darker still—corruption, abuse, shame, and moral decay. Sharma doesn’t write for catharsis. He writes because the wound needs air.

Tishani Doshi: Of Feminism, Landscape, and the Luxury of Saying No

Now shift gears slightly—and gently—into the lyrical world of Tishani Doshi, where solitude isn’t loneliness, and rebellion can sound like a whisper.

In Small Days and Nights (2019), Doshi gives us Grace, a woman who leaves her marriage, returns to Tamil Nadu, and chooses to raise her sister—with Down syndrome—in an isolated coastal town.

“I didn’t want to be a good person. I only wanted to be free.”

It’s not a line. It’s a manifesto.

Doshi is a poet, dancer, novelist—and possibly part-oracle. Her prose is sensual, slow-burning, and steeped in earth, salt, and introspection. She writes about women who walk away, not to escape, but to become.

Her poetry, like Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods, punches with grace. Her novels flow like diaries with spine.

Tishani Doshi isn’t writing for recognition. She’s writing from refusal—to conform, to explain, to shrink.

Anuradha Roy: The Historian of Forgotten Heartaches

Optional in name, but essential in spirit—Anuradha Roy deserves a final nod.

In Sleeping on Jupiter (2015), All the Lives We Never Lived (2018), and The Earthspinner (2021), Roy weaves intimate lives into epic silences. Her novels are full of people who’ve been historically overlooked—women, artists, lovers, dissenters, refugees.

“Sometimes, the worst part of holding the secret is not the pain. It’s the silence.”

Her prose is polished, patient, unhurried—but emotionally loaded. She doesn’t chase drama. She lets it rise from the cracks of trauma, war, exile, and memory.

Roy is the kind of writer who could make you cry over a broken pot—and then remind you that the pot was colonised, too.

Imagined Scene: Literary Airbnb with Wi-Fi and Existential Crises

Picture this:

Avni Doshi is refusing to share a kitchen with her mother.

Megha Majumdar is live-streaming the entire experience, while warning others to clear their cookies.

Akhil Sharma is sitting in a corner quietly bleeding into a legal pad.

Tishani Doshi has gone for a barefoot walk by the sea and left a note: “Back in five years.”

Anuradha Roy is reading everyone’s old love letters and underlining the parts that still hurt.

They do not agree. They do not perform. They write—and let the wound narrate.

What They Gave Us

These writers brought Indian English fiction fully into the contemporary conversation. Their stories aren’t framed by Partition or the Empire. Their conflict isn’t East vs. West. It’s self vs. self. They write of things you can’t post on Instagram:

The boredom of arranged marriage

The guilt of survival

The smell of exile

The inheritance of trauma

And the tiny revolutions inside tea-stained notebooks

They don’t ask for sympathy. They dare you to witness.

They write about India, yes—but not the one in tourist brochures. It’s the India inside therapy rooms, courtrooms, WhatsApp chats, and memory gaps. The India you don’t post about.

As ABS folds the scroll, still humming the poetry of pain and smiling wryly at yet another emotionally dysfunctional dinner scene, there’s a sense that Indian English fiction has stopped explaining itself. It simply is. Brutal. Beautiful. Unbothered.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

Who once read a Tishani Doshi line and didn’t speak for two hours (but silently judged someone for pronouncing diaspora as “die-uh-spora”)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance