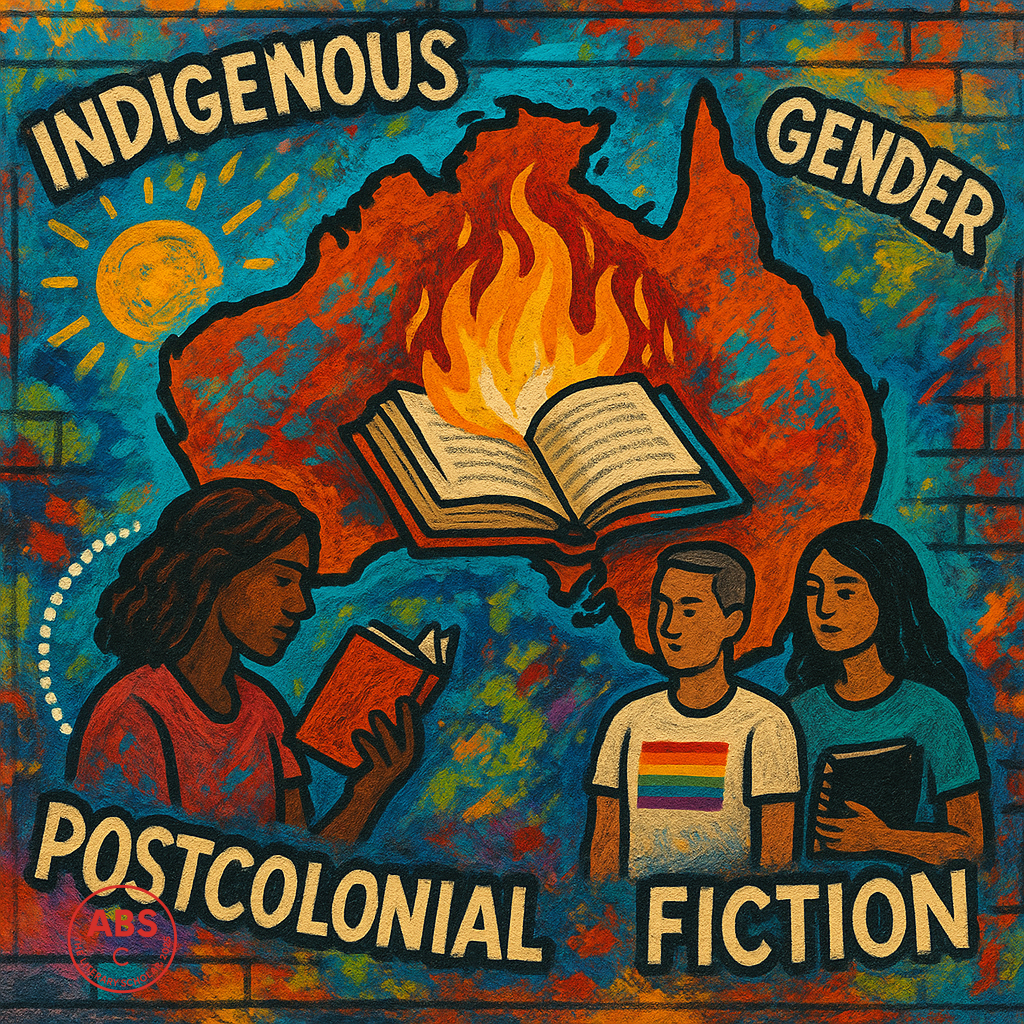

From Indigenous power to postcolonial punchlines, gender rebellions to literary reinventions—Australia writes with bite now.

By ABS, who believes that modern Australian fiction has learned to throw boomerangs made of metaphor—and they rarely miss.

f early Australian literature was written on the backs of convicts and mid-century fiction was dipped in despair, then modern AusLit is an intellectual brawl in a bookstore café. The sentences are sharper, the plots more restless, and the voices louder than a kookaburra in therapy.

This is Australia after the self-doubt wore off—and the writers stopped asking, “Are we literary enough?” and started declaring,

“Move over, we’ve got something to say—and it won’t be edited for comfort.”

Indigenous Voices: The Oldest Storytellers Get the Mic Back

After centuries of being erased, stereotyped, or politely “anthologized,” Indigenous Australian writers are now writing the narrative instead of surviving it—and changing everything we thought we knew about what literature can do.

✦ Kim Scott (Benang, That Deadman Dance)

He doesn’t just write novels. He rewrites history. With lyrical force and brutal honesty, Scott reclaims Noongar identity, language, and land from the margins.

✦ Melissa Lucashenko (Too Much Lip)

Brutal, funny, unfiltered—Lucashenko’s work comes at colonialism with a crowbar, a smirk, and the kind of sentences that leave bruises.

✦ Alexis Wright (Carpentaria, The Swan Book)

Visionary, surreal, and unapologetically political, Wright doesn’t write books—she summons nations into being.

This isn’t “representation.” It’s reclamation with narrative teeth.

Postcolonial Fiction: Writing Back with a Pen in One Hand and a Flame in the Other

Modern AusLit also belongs to those who grew up in the shadows of empire and now treat the Queen’s English like a borrowed coat—wear it, reshape it, or toss it if it doesn’t fit.

Writers like:

Nam Le (The Boat): Vietnamese-Australian brilliance in short stories that jump continents and cut deep.

Maxine Beneba Clarke (Foreign Soil): Bold, fierce, and politically charged fiction rooted in the African diaspora.

Sofie Laguna, Christos Tsiolkas, and others who write Australia from the cracks in its identity—where violence, vulnerability, and heritage collide.

Their stories are not designed to make readers comfortable. They are designed to make them think. And squirm. And question the shape of a nation.

Urban, Angry, Gender-Bending, Genre-Breaking

This era has no aesthetic loyalty. Fiction collides with memoir. Verse becomes manifesto. Identity spills off the page and into performance.

Claire G. Coleman (Terra Nullius): Sci-fi meets Indigenous resistance.

Ellen van Neerven (Heat and Light): Queer, experimental, and impossible to classify.

Bri Lee (Eggshell Skull): Legal memoir as gendered scream.

The topics? Race, class, climate, mental health, gender, power.

The style? Unruly, unpredictable, and so good it’s terrifying.

Themes That Refuse to Behave

Land as both trauma and ancestor

Language as survival and subversion

Gender as fluid as a desert storm

History as something to be dragged out, questioned, and rewritten

Identity not as a category, but as a conversation in motion

Australia Today: No Longer Just the Bush and the Beach

Modern Australian fiction no longer tries to fit a national costume. It burns it.

It’s not just white men in Akubras anymore. It’s First Nations futurism, immigrant rage, queer joy, feminist fury, and literary invention all in one dizzying, powerful scroll of voices.

This is not the Australia that was discovered—it’s the one that’s being written, every single day.

ABS closes the scroll with a spark in the margins, as stories rise like smoke from burnt syllables and still-warm ink.

Signed,

ABS, The Literary Scholar

Who believes that literature stops being “national” the moment it starts being honest—and modern Australian writers are done playing nice.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance