By ABS, The Literary Scholar

(Who firmly believes Charles Dickens invented the term “it’s complicated” long before modern romance and plotlines did)

If you’ve ever wished life came with more eccentric characters, more dramatic coincidences, and more men with tragic backstories and suspicious facial hair—look no further than the pen of Charles Dickens, the man who turned serialized suffering into high art and turned ninety-seven minor characters into a paragraph about soup.

And at the heart of Dickens’s legacy lies his literary child—perhaps even his favorite—David Copperfield. A novel he called his “favourite child” and which, let’s be honest, reads like an emotional rollercoaster built on orphan tears, villainy, redemption, and a small army of unforgettable people, each with a walking style and nose type all their own.

David Copperfield: Born Late, Cried Early

We meet David at the very moment of his birth. Not just any birth—he arrives posthumously. His father is already dead. So, welcome to the world, David: no dad, an adorably fragile mother, and a creepy soon-to-be stepfather hovering in the future.

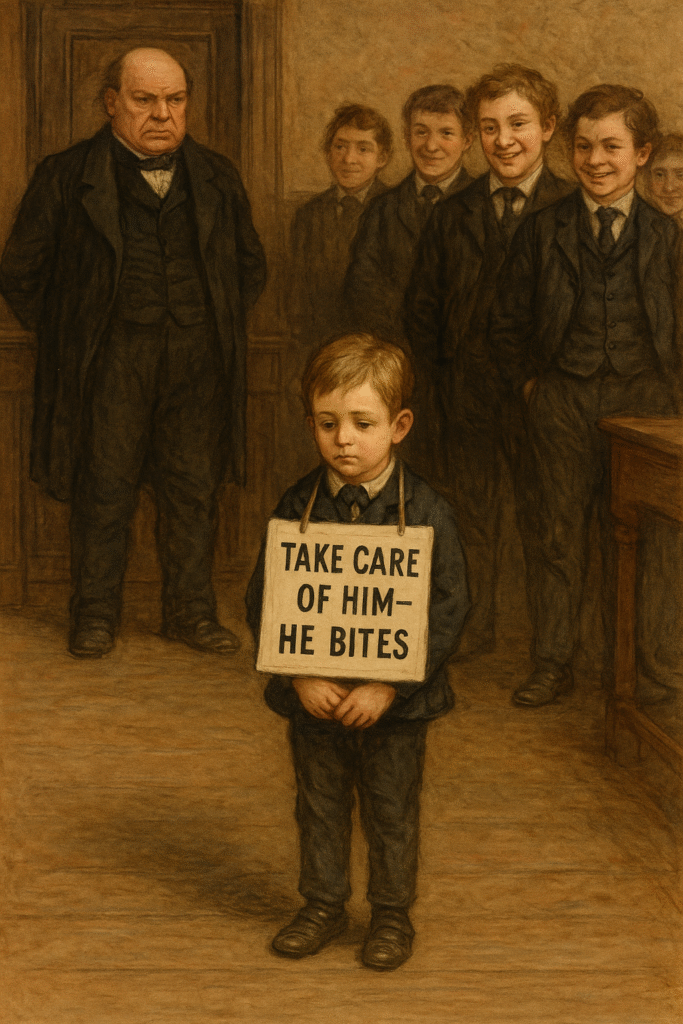

Soon enters Mr. Murdstone—whose name practically screams villain—and with him, the “firm hand” that Victorian novels often confuse with outright cruelty. Add a spiteful sister (Miss Murdstone) with the emotional warmth of a damp sponge, and David is exiled to a school where children are beaten, berated, and occasionally educated.

There he meets James Steerforth, rich, charming, and a walking cautionary tale. A foreshadowing in trousers. But we’ll get to that downfall later.

From Aunt Betsy to Book Deals: The Copperfield Odyssey

After his mother’s death (and baby brother’s, because in Dickens’s world grief rarely travels alone), David runs away to his great-aunt Betsey Trotwood—a woman so no-nonsense, her name comes with its own carriage of sarcasm.

Betsey Trotwood is a gem. Sharp-tongued, stern-faced, but with a soft centre that would make a Victoria sponge weep. She takes David in, rescues him from a Dickensian downward spiral, and sends him to school.

“Never,” said Miss Betsey, “be mean in anything; never be false; never be cruel.”

(And in brackets she may as well have added: Unless you are a character in this book.)

Enter the Characters: A Parade of Peculiar Perfection

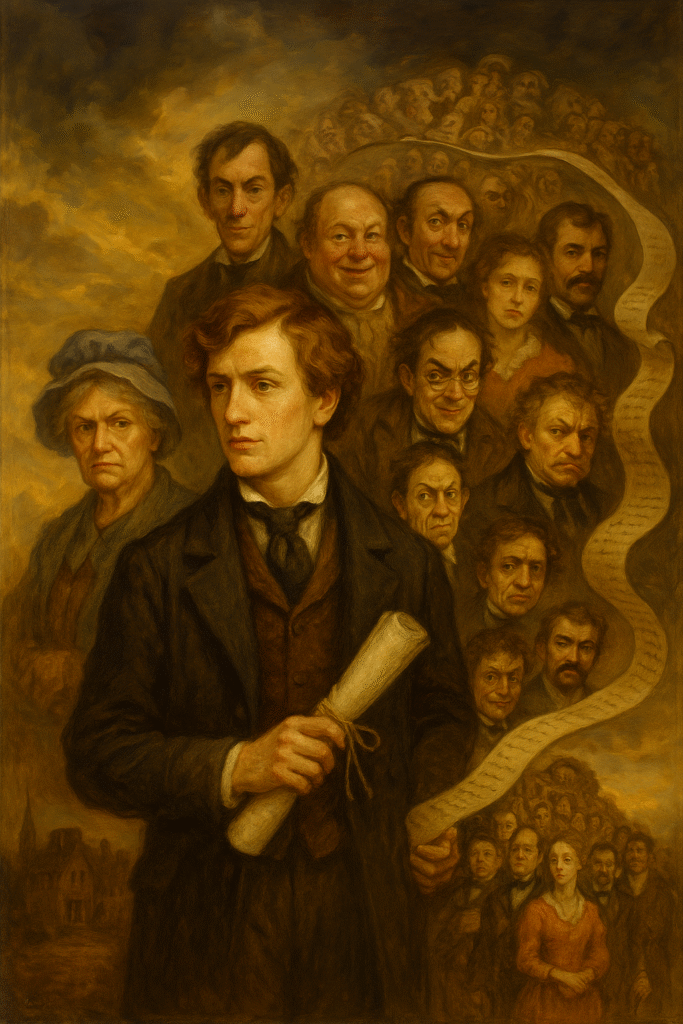

This is where Dickens flexes his true gift: characterization so vivid, you feel they’ll walk off the page and start charging rent.

Uriah Heep: A masterclass in unctuous villainy. Always “‘umble,” always scheming, with hands described like cold, sticky eels. The man could curdle milk with a glance.

Mr. Micawber: One of Dickens’s greatest comic creations. Endlessly broke, perpetually optimistic, and always ready with a speech that could exhaust a thesaurus.

“Something will turn up,” he says—and if not, he’ll turn up anyway, at the most inconvenient moment.

Dora Spenlow: David’s first wife. Pretty, fragile, a domestic disaster with the emotional depth of a Victorian teacup. She dies young, leaving David to realise he married a decorative lamp with feelings.

Agnes Wickfield: Dora’s complete opposite. Sensible, loyal, wise—and waiting in the background like a résumé on hold.

And then there are others: Peggotty, Ham, Emily, Traddles, Barkis (who is willing), Mr. Creakle, Miss Mowcher, Mrs. Gummidge, and—somehow—everyone has their own subplot, side quest, emotional monologue, and culinary preference.

If you can’t keep up, it’s because Dickens didn’t want you to—he wanted to overwhelm you with humanity.

Dickens the Puppeteer: Plot, Coincidence, and a Bit of Magic

The beauty—and madness—of David Copperfield is that everything eventually connects. You just have to survive a few detours, seven deaths, three financial collapses, and one shipwreck to see it happen.

Steerforth turns out to be the villain you expected, seducing Emily and disgracing the Peggottys. Ham dies trying to rescue him (poetic irony with thunder effects). Mr. Micawber exposes Uriah Heep’s fraud (with the flair of a bankrupt Sherlock Holmes). And David, who has suffered more plot than most national epics, finally becomes a successful writer.

Which, surprise, is exactly what Dickens did with his own life. Because, yes, David Copperfield is quasi-autobiographical, which is Victorian for: “I made this all up but also definitely lived it.”

Dickens: Master of Characterization (and Exhaustion)

Charles Dickens had one eye on humanity and the other on theatre. He gave his characters quirks, tics, verbal habits, and visual signatures that made them unforgettable.

Nobody in Dickens is generic. Everyone has a specific way of sitting, sneezing, walking, or obsessing about receipts. His novels don’t have side characters—they have satellite galaxies of personality.

His genius? He could sketch the soul of a person in half a sentence and still make you weep over their pension problems.

Beyond David: The Dickens Universe

Though David Copperfield is arguably his most personal, it’s only one station on the Dickens Express. Consider:

Oliver Twist: More orphans. More misery. The only book where asking for “more” causes a riot.

Nicholas Nickleby: A crusade against school abuse, villains in velvet waistcoats, and another hero with a moral compass so strong it defies magnetic fields.

A Tale of Two Cities: Less quirky characters, more French Revolution. But still, Dickens manages to sneak in the most famous literary mic-drop ever:

“It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done…”

His world is always groaning with life. Yes, it’s exaggerated. Yes, it’s sentimental. But oh, how alive it feels.

Final Thoughts from the Creaking Stage

Charles Dickens didn’t just write stories. He constructed carnivals of humanity, with characters juggling comedy and tragedy, satire and sincerity. His novels aren’t light reading—they’re literary obstacle courses, and David Copperfield is the marathon.

But through all the plot twists and parenthetical trauma, what endures is his belief in redemption. No matter how absurd or broken his characters, he finds a way to offer them dignity—or at least a memorable exit.

He reminds us that people—real and fictional—are rarely simple. They’re layered. Messy. Endearing. And worthy of page after page after page.

Action of ABS, The Literary Scholar

(Packs a suitcase with 90 supporting characters, unrolls a scroll longer than Uriah Heep’s apology list, and walks off into the fog mumbling, “Barkis is willing… but I am weary.”)

Who still hasn’t met a Dickens character that doesn’t look vaguely like someone in their WhatsApp group.

And believes that if Dickens were alive today, he’d be writing character descriptions for LinkedIn—and they’d all go viral.

Still emotionally recovering from Miss Betsey Trotwood’s glare

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance