Resistance Literature from the Streets of Soweto to the Cells of Lagos

From ABS, Who Believes metaphors are weapons, especially when the censors don’t get them.

When your country jails dissidents, bans books, and declares “everything is fine” while tanks roll past bookstores, you either stop writing or you learn to write like a ninja.

Africa chose the latter.

Welcome to the world of resistance literature, where poetry is smuggled through metaphor, novels wear the face of fiction but scream reality, and plays are staged in silence—because someone’s always listening.

Dictators came with uniforms. Writers came with pens.

Spoiler: the pen still writes.

The Revolution Will Be Written—In All Caps

Post-independence Africa was supposed to be a sunrise. Instead, in many countries, it turned into a fog of one-party states, coups, censorship, and leaders who loved mirrors more than constitutions.

But writers knew something the dictators didn’t: you can shut a press, but not a pen.

You can silence a journalist, but not a metaphor.

And so, they resisted—with ink.

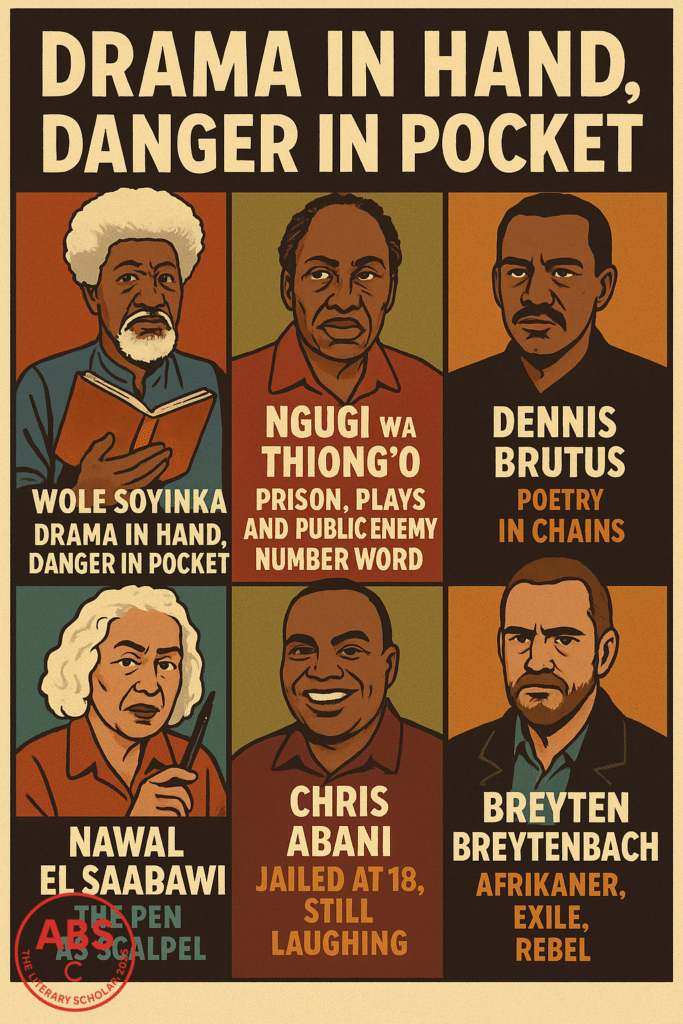

Wole Soyinka: Drama in Hand, Danger in Pocket

Start with Wole Soyinka, because we always should. When Nigeria spiraled into political chaos in the 1960s, Soyinka didn’t write a polite op-ed. He seized a radio station.

Yes. A literal radio station.

He was arrested, tortured, and thrown into solitary confinement for 27 months. But that only gave him time to compose The Man Died, a prison memoir so sharp, it still bleeds.

His plays, from Kongi’s Harvest to A Play of Giants, ridiculed despots with lyrical savagery.

He didn’t just survive dictators—he heckled them.

Soyinka was the resistance—dignified, unafraid, and devastatingly articulate.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: Prison, Plays, and Public Enemy Number Word

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Kenya’s literary lion, knew that to challenge power, you must first challenge the language that props it up.

His decision to stop writing in English and switch to Gikuyu wasn’t just a cultural move—it was political warfare.

And when he co-wrote I Will Marry When I Want, a powerful play exposing land grabs, capitalism, and class hypocrisy, the government rewarded him with… jail.

What did Ngũgĩ do in prison?

Write.

On toilet paper.

The result: Devil on the Cross—a novel where the devil himself attends a capitalist showcase. Subtle? No. Effective? Absolutely.

He made literature the resistance, and resistance the literature.

Dennis Brutus: Poetry in Chains

Dennis Brutus didn’t have the luxury of metaphor. A South African anti-apartheid activist and poet, he was shot in the back by police while trying to escape arrest. He was jailed on Robben Island alongside Mandela.

His poetry—raw, melancholic, urgent—was often banned.

Collections like Letters to Martha were written as if whispering across barbed wire.

They didn’t romanticize suffering. They reported it, carved in verse.

Brutus showed that poetry didn’t need to rhyme. It just needed to refuse.

Nawal El Saadawi: The Pen as Scalpel

Egypt’s Nawal El Saadawi fought two dictatorships, a patriarchal system, religious fundamentalism, and the very idea that women should write at all.

A doctor, feminist, and literary grenade, she was imprisoned for her activism and blacklisted for her books.

Her novel Woman at Point Zero is a manifesto against state-sanctioned misogyny and moral hypocrisy.

The main character kills her abuser and waits, unrepentant, for execution.

El Saadawi didn’t write to please.

She wrote to pierce.

Chris Abani: Jailed at 18, Still Laughing

Nigerian writer Chris Abani published his first novel at 16. It was about a fictional coup. The government assumed he was planning a real one.

Result: Jail.

His next book also led to prison. His play? Same result. By the time he was 21, he had been jailed three times, tortured, and threatened with execution.

Abani later moved to the U.S., where he writes poetry and essays with humor so dark it’s practically solar eclipse.

His TED Talks are a masterclass in turning trauma into grace.

Breyten Breytenbach: Afrikaner, Exile, Rebel

A white Afrikaner poet who opposed apartheid, Breyten Breytenbach had every privilege—and rejected it.

He married a Vietnamese woman (illegal under apartheid), joined anti-apartheid movements, and was jailed for alleged terrorism.

His poetry, like Voice Over, and his prison memoir The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist are filled with rage, wit, and dreamlike resistance.

In a regime obsessed with race, Breytenbach used his words to bleach out bigotry.

Resistance Comes in Layers

Not all resistance is loud. Sometimes it’s a whisper, a proverb, a character who just refuses to conform.

Writers like Tsitsi Dangarembga, Jack Mapanje, Kalamu ya Salaam, and Nuruddin Farah told stories that danced around censorship while aiming squarely at power.

From Rwanda to Sudan, Angola to Uganda, literature became the last space where truth could survive—barefoot, maybe, but breathing.

What the Censor Missed

Here’s the thing about dictators: they don’t read carefully.

They ban the obvious. They miss the symbolism.

They shut down newspapers but forget that lullabies can carry revolution.

That folktales can contain sabotage.

That a haiku can take down a strongman’s speech.

African writers knew this. They wrapped bombs in beauty.

And while tyrants strutted on TV, novelists were planting ideas in the margins.

Whispers grew. Symbols echoed.

And suddenly, the emperor looked… overdressed.

ABS brushes off a page still damp with defiance.

Outside, sirens wail. But inside the scroll, poetry laughs, still undefeated.

Where dictators once burned books, metaphors now smolder—and truth waits with perfect posture.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar who believes every jail cell secretly echoes with unfinished poems.

And sometimes, resistance wears the mask of a story that refuses to bow.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance