Colonialism, Culture Clashes, and Why Chinua Achebe Had Every Right to Be Annoyed

From ABS, Who Believes stories survive empires, but sarcasm survives history.

It begins, as most tragic tales do, with someone arriving uninvited.

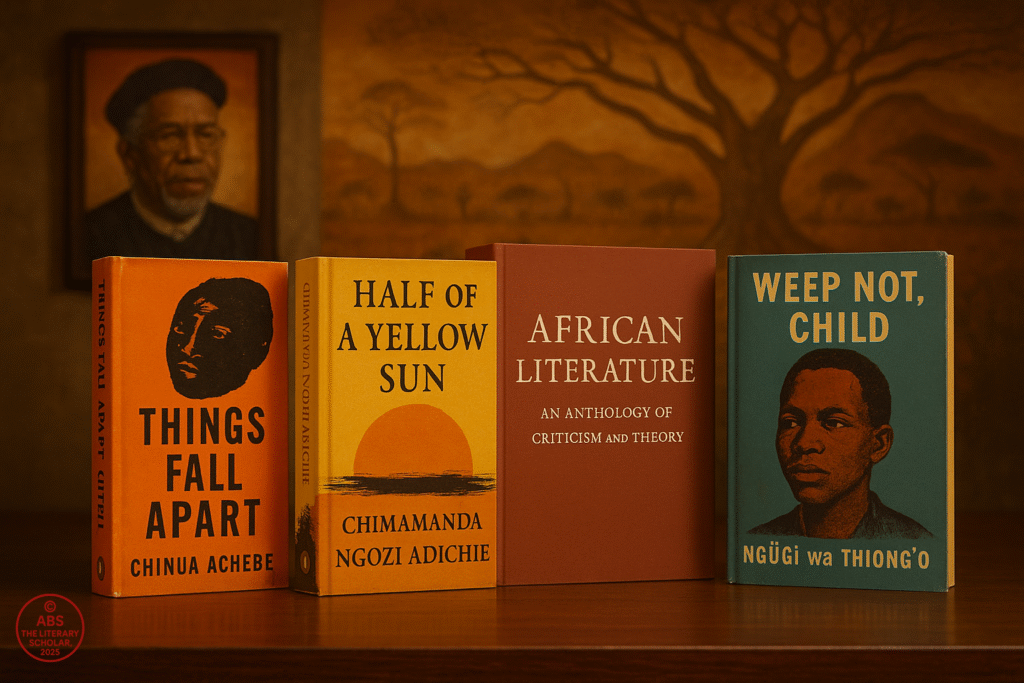

Long before PowerPoint presentations and TED Talks about “cultural sensitivity,” colonial powers marched into Africa with swords, Bibles, and the smug conviction that everyone needed a good dose of Britishness. What followed was a literary paradox: while land was stolen and cultures suppressed, a vibrant body of literature was born—often in the very language of the colonizer. That’s the original irony that African literature wears like a battle scar: resistance written in English.

And no one stitched that scar with more dignity and precision than Chinua Achebe, the grandfather, the gatekeeper, and—let’s be honest—the man who finally made Joseph Conrad squirm posthumously.

The Achebe Awakening: When Things Fell (Deliberately) Apart

Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) wasn’t just a novel. It was a thunderclap aimed at colonial arrogance and literary condescension. Until then, most of Africa in English literature looked like a National Geographic safari narrated by a mildly racist uncle. Enter Achebe: a Nigerian Igbo intellectual who decided to show the world that African societies had structure, law, beauty, complexity—and, yes, plenty of dysfunction even before Europeans arrived, thank you very much.

Okonkwo, the protagonist, was no saint. But he was human—and in the colonial literary gaze, humanity was a privilege rarely extended to African characters.

Achebe’s writing had the pulse of oral tradition, the rhythm of proverbs, and the sharpness of satire. And his message was clear: “We had our stories long before you came to tell us yours.”

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: The Man Who Cancelled English (Before It Was Cool)

While Achebe chose to write in English to reach the colonizer in their language, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o of Kenya chose to break up with English altogether. After early novels like Weep Not, Child and A Grain of Wheat, Ngũgĩ declared linguistic independence and began writing in Gikuyu. This wasn’t just a switch—it was a literary rebellion.

To Ngũgĩ, language was the oxygen of culture. Writing in English, he argued, meant inhaling imperialism and exhaling dependency. His 1986 essay Decolonising the Mind is still the literary equivalent of a Molotov cocktail hurled into the British Council.

And when the Kenyan government didn’t like what he wrote? They locked him in prison. He wrote a play on toilet paper. Because writers like Ngũgĩ don’t ask for permission—they just find more surfaces.

Wole Soyinka: Nobel, Satire, and Theatrical Fury

Then there’s Wole Soyinka, the first African to win the Nobel Prize in Literature (1986), which he did without ever writing about quaint villages or adorable orphans.

Soyinka’s plays—like Death and the King’s Horseman, The Lion and the Jewel, and A Dance of the Forests—blended Yoruba mythology, biting political commentary, and absurdist humor. He used theatre the way some use dynamite: strategically, and with a smirk.

When he wasn’t writing, Soyinka was in prison. Or criticizing dictators. Or being exiled. Or teaching. Or all of the above. Basically, Wole Soyinka is what would happen if Shakespeare, Fela Kuti, and George Carlin had a baby and made him read The Economist.

His most dangerous weapon? Irony. And probably the fact that he made tyrants look stupid—often in iambic pentameter.

The Empire’s Literary Hangover: And the Rest of the Riot

These literary revolutionaries didn’t rise in isolation. The entire African continent was simmering with voices:

Bessie Head (South Africa/Botswana), who fled apartheid and wrote with exquisite psychological insight (Maru, When Rain Clouds Gather).

Ayi Kwei Armah (Ghana), whose The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born used metaphors so intense, they should’ve come with a health warning.

Mongo Beti (Cameroon), whose satire Mission to Kala made fun of both colonial education and postcolonial confusion.

Ama Ata Aidoo (Ghana again—clearly something in the water), who delivered The Dilemma of a Ghost with feminism and fire, long before it became a university module.

These writers explored what it meant to inhabit fractured identities: African, colonized, English-speaking, and resistant. And they did so with prose that was both lyrical and lacerating.

Colonialism gave Africa borders. Literature tore them down.

And Then There Was the English Problem

If colonialism was the disease, English was the “gifted” parasite. Most African writers had to decide: do I use the master’s tongue to unwrite the master’s narrative? Or do I reclaim my mother tongue, even if the publishing industry raises a colonial eyebrow?

There’s no simple answer. Achebe defended writing in English, saying he was bending it to African shapes. Ngũgĩ said it couldn’t be bent—it had to be replaced. Soyinka? He just used whatever language made the satire sharper.

But what they all knew was this: language was never neutral.

A Literature That Refused to Be a Footnote

These writers didn’t wait for validation. They didn’t write for literary prizes (though they collected them anyway). They wrote because their nations were cracking under imported systems, and someone had to write the truth before history could lie again.

And while their British counterparts were still writing about the weather and existential ennui, African writers were unpacking entire centuries of cultural trauma, resilience, and reinvention—often in fewer pages and with far better dialogue.

ABS stands at the edge of a broken atlas, where ink has replaced empire.

Pages rustle like distant drums, echoing not conquest but memory.

Somewhere between Achebe’s silence and Soyinka’s satire, a scroll is folded—not closed.

The story continues, even if the colonizers have exited the stage.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Scholar who believes decolonisation isn’t just political—it’s poetic.

It’s the moment a proverb outlives a propaganda.

And the pen, against all odds, writes back.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance