A Love Story, A Loan Agreement, And A Courtroom Drama That Could Give Any Lawyer Insomnia

Let us talk about The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare’s charming little cocktail of romance, wit, borrowed money, and casual racism that he wrote long before HR departments existed. This is the play where Venice behaves like the original financial capital of the world and everyone is running around making terrible decisions in the name of love, friendship, and shiny boxes. Shakespeare, meanwhile, watches from the background thinking, Look at them, they still think they are in control.

Shakespeare wrote this comedy when he clearly needed an outlet for his obsession with contracts. Forget fairy woods and mistaken identities. Here he gives us a moneylender who wants a pound of flesh, a merchant who signs things without reading the fine print, and a heroine who solves legal problems while disguised as a lawyer. Honestly, if Shakespeare were alive today, he would be sued for offering legal advice without a license and then he would write another play about it.

The Venice of this play is not your romantic gondola brochure Venice. This Venice is a marketplace for emotions where love is traded, loyalty is priced, and friendship comes with interest. We meet Antonio, the saddest merchant ever created, who spends the entire play looking like someone stole his last samosa. Then there is Bassanio, the charming gentleman who manages his finances with the seriousness of a teenager buying cryptocurrency. And Shylock, the man who carries the rage of centuries in one contract and still calculates interest better than all of them.

The comedy floats on Shakespeare’s favorite tricks. Confusion, disguise, demands for justice, sudden mercy, and the eternal truth that people in love lose ninety percent of their intelligence. Add Portia whose mind works sharper than all Venetian courts combined and you get a play that mixes laughter with moral discomfort. This comedy smiles at you while quietly stabbing you with a question. Who is right. Who is wrong. And why are the lovers so dramatic.

Before we enter the scroll, remember one thing. Shakespeare never promised a happy ending. He only promised entertainment and then left the audience to deal with the consequences. Welcome to Venice where your best friend borrows money in your name and your enemy wants your body parts as collateral.

ABS Believes

ABS believes that this play is not just a comedy. It is Shakespeare’s clever social experiment where he tests how far humans will go when pride, prejudice, and love collide in one messy Venetian alley. ABS also believes that Portia deserved her own spin off series, that Antonio needed therapy, and that Bassanio should never be allowed near a loan document again.

ACT ONE

Where Venice Learns That Friendship Is Expensive And Love Is Even Costlier

Act One opens with Antonio, Venice’s most emotionally gifted merchant, wandering around the city like someone who misplaced his happiness in a gondola. Shakespeare never tells us why he is sad. ABS suspects Antonio woke up, looked at his business, his friendships, his investments, and thought, my destiny is determined by weather reports.

Salerio and Solanio try to diagnose Antonio’s sadness with the confidence of men who know absolutely nothing. They blame his ships. They blame his investments. They even suggest he might be in love. Antonio denies everything like a man defending himself in court without a lawyer.

“In sooth I know not why I am so sad.”

Translation in ABS tone,

I have no clue why I am sad but I am fully committed to it.

Antonio’s friends exit after offering zero help, proving that friendship in Venice is mostly decorative. Enter Bassanio, Lorenzo, and Gratiano. Gratiano tries to cheer Antonio up by advising him to smile more. Which is funny because Gratiano himself speaks like a fireworks display that refuses to turn off. Antonio tells him he laughs too much. Gratiano counters that Antonio broods too much. This is the Elizabethan version of, you need therapy.

Bassanio finally pulls Antonio aside, which is Shakespeare’s signal that financial foolishness is approaching. Bassanio begins gently. He is broke. Again. He needs money. Again. Antonio, whose heart overpowers his brain every single time Bassanio appears, agrees before hearing the details.

Now comes the real revelation. Bassanio wants to marry Portia of Belmont. Not just Portia but the Portia, the wealthy heiress with gold, intelligence, elegance, and a strict father who invented an escape room challenge centuries before escape rooms were cool. Bassanio talks about her with such admiration that Antonio practically dissolves into emotional mist.

“In Belmont is a lady richly left.”

ABS translation,

She has money, I do not, therefore destiny calls.

Antonio explains that he has no ready cash because all his wealth is floating across oceans. His ships are basically traveling bank accounts. But he still tells Bassanio to borrow the needed amount in Antonio’s name. This is friendship at the level where your heart signs agreements your brain should never approve.

Meanwhile Shakespeare transports us to Belmont, where Portia sits with Nerissa and delivers some of the finest female intelligence of the entire canon. She is exhausted by suitors who are too proud, too dull, too serious, too loud. Portia is the queen of silent judgment and she does it beautifully.

Nerissa reminds her that her father, the magician of inconvenient wills, locked her marriage behind three caskets. Gold, silver, lead. Choose the right one and win Portia. Choose wrong and go home humiliated. It is basically an ancient quiz show but with real emotional consequences.

Portia admits she remembers Bassanio fondly. He impressed her earlier in life. He shines among suitors like a candle in a room lit by disappointment.

“Her name is Portia, nothing undervalued.”

Back to Venice. Bassanio and Antonio approach Shylock, Venice’s financially precise moneylender, to borrow the amount. Shylock enters with the energy of a man who has loaned money for too long and knows exactly how unreliable humans can be. Bassanio explains the need. Shylock mentally examines Antonio’s credit score and sees thunder clouds.

Antonio openly insults Shylock. Shylock quietly resents Antonio. Now they want to sign a contract together. Shakespeare is clearly having fun.

Shylock offers the infamous bond. If Antonio fails to repay the loan on the agreed date, Shylock will claim a pound of Antonio’s flesh. Bassanio is horrified. Antonio laughs because his optimism is stronger than his financial sense. Shylock remains calm, almost serene, like a man who has discovered a beautifully ironic loophole.

“If you repay me not on such a day your forfeit must be a pound of your fair flesh.”

ABS translation,

If your ships sink, you become legal meat.

Antonio signs the bond instantly. Bassanio panics internally. Shylock smiles like someone who has just won a philosophical argument. Shakespeare slowly rubs his hands because he knows this comedy is already dipping its toes into tragedy.

Act One closes with love declared, money borrowed, flesh gambled, and Portia waiting in Belmont without knowing a financial storm is about to hit her future husband. Shakespeare has set the stage. ABS raises a brow. Venice holds its breath.

ACT TWO

Where Venice Plays Hide And Seek And Belmont Turns Into A Marriage Reality Show

Act Two begins by introducing us to Launcelot Gobbo, the human version of a confused puppy. He works for Shylock but wants to run away because he is convinced staying in Shylock’s house is equal to slow spiritual decay. Launcelot debates his own conscience like a one man parliament. His conscience tells him to stay. His devilish side tells him to leave. Naturally, he listens to the devil. Shakespeare smiles because this is the Elizabethan idea of comedy.

Launcelot meets his blind father Old Gobbo, who hilariously does not recognize his own son. What follows is a scene of such dramatic confusion that even Shakespeare probably wondered why he wrote it. Launcelot tricks his poor father, then finally reveals his identity in the most theatrical way possible.

“I am Launcelot, your boy that was, your son that is.”

ABS translation,

Congratulations, you are still my father.

Next, Launcelot joins Bassanio and immediately begs for a new job. Bassanio, who never refuses anything because it might require responsibility, hires him instantly. This is the kind of HR Venice actually needed.

Now comes the subplot of Jessica, Shylock’s daughter. Jessica is done with the gloomy Shylock household. She plans to escape with Lorenzo, a Christian. This is Shakespeare’s universal formula. Strict father. Romantic daughter. Elopement. Drama. Repeat in every age.

Jessica writes Lorenzo a secret letter describing her escape plan. Lorenzo, who moves with the speed of a man running toward free dessert, gathers his friends and prepares for the midnight getaway.

Jessica stands at her window holding the letter of her future and sighing like she is auditioning for the role of Juliet.

“I am sorry thou wilt leave my father so.”

Her guilt lasts about three seconds.

As the night arrives, Jessica disguises herself as a page boy. This is a pattern Shakespeare loves. Women in disguise. Men confused. Audiences entertained. Jessica throws money, jewels, and her entire inheritance into Lorenzo’s arms, then runs away from her father without looking back.

Back at Shylock’s house, he senses something is wrong. His entire spirit becomes a weather forecast of doom. He warns his servant Launcelot that Christian gatherings are dangerous, music is sinful, and he should lock the doors. But Shylock leaves home with the worst timing imaginable because Jessica slips out the moment he turns the corner. Venice must have laughed for days.

Now we rush from Venice to Belmont, which has officially turned into Shakespeare’s version of a marriage game show. Welcome to The Casket Challenge. Contestant number one, the Prince of Morocco. He arrives with royal confidence, handsome speeches, and the swagger of a man who has never lost anything in his life.

Portia, being Portia, handles him with perfect politeness but internally wonders if she can speed up the casket choosing process. Morocco reads the inscriptions on the three caskets. Gold. Silver. Lead. He thinks like a man dazzled by his own reflection.

“Who chooseth me shall gain what many men desire.”

Morocco chooses gold. Of course he does. Gold opens. Inside lies not Portia but a skull and a poem reminding him that appearances deceive. Morocco exits with the dignity of a man pretending this never happened.

Portia does not hide her relief. Portia’s father may have invented the casket test, but Portia is silently cheering every time a wrong suitor eliminates himself.

Now comes the Prince of Arragon, the man whose arrogance can be seen from space. He reads the caskets, decides that gold is too vulgar, lead is too cheap, so he chooses silver because he deserves exactly what is due to him. His superiority complex is the real casket here.

“Who chooseth me shall get as much as he deserves.”

Arragon opens the silver casket and finds, not Portia, but a portrait of a fool. Belmont applauds silently. Portia rolls her eyes elegantly.

Meanwhile Venice continues its chaos. Salarino and Solanio run around reporting gossip like medieval news reporters. Lorenzo and Jessica have vanished successfully. Shylock discovers the escape and erupts into one of the rawest emotional scenes of the entire play. His daughter is gone. His money is gone. His jewels are gone. His trust in the world is shattered. Shakespeare does not treat this lightly. Shylock’s grief is loud and deeply human.

“My daughter! O my ducats! O my daughter!”

ABS translation,

My child is gone and so are my savings. Why must destiny attack both at once.

To make matters worse, Antonio’s ships begin to fail. Rumours spread that his ventures are wrecked on the seas. Venice can already sense the bond tightening around him.

Act Two ends with Portia praying that Bassanio arrives soon, Shylock swearing revenge, Antonio’s future sliding toward danger, and Venice humming with tension. Shakespeare has set every trap, lit every fuse, and positioned every character exactly where he needs them.

ABS looks at the horizon and says,

The comedy is smiling but the tragedy is warming up.

ACT THREE

Where The Storm Breaks, The Lovers Hope, And Antonio’s Luck Commits Suicide

Act Three arrives like a thunderclap. Every plot point Shakespeare placed earlier now starts exploding one by one. Venice stops pretending to be calm. Belmont stops pretending to be elegant. And Antonio’s ships stop pretending to float.

We begin with Solanio and Salarino acting like Venice’s gossip radio. They whisper the terrible news. Antonio’s ships, the ones he casually risked his flesh for, are breaking on foreign coasts like soggy biscuits. Venice is murmuring. Moneylenders are smiling. And Antonio is suddenly the most unfortunate man in Europe.

“A kinder gentleman treads not the earth.”

This is Shakespeare’s polite way of saying Antonio is a lovely man with the financial luck of a wet leaf. Solanio and Salarino actually pity him and that is how you know Antonio is in serious trouble.

Then comes Shylock. He enters like a storm that finally found land. His rage is not small or quiet. It is the kind of rage that has been boiling for years. Jessica is gone. His gold is gone. His jewels are gone. His trust is shattered. And the city that mocked him now wants sympathy.

Shylock responds with one of the greatest speeches in literature. A speech that tears into centuries of prejudice with surgical precision.

“Hath not a Jew eyes… If you prick us do we not bleed.”

ABS translation,

You treated me as less than human. Do not expect me to behave like a saint.

This is not comedy anymore. Shakespeare is holding a mirror and Venice looks ugly.

Shylock demands justice. He demands the bond. One pound of Antonio’s flesh. No negotiations. No apologies. He tells them Antonio insulted him, mocked him, spat on him, and now wants mercy. He refuses. In his mind, justice must echo the hurt he has lived with all his life.

Meanwhile in Belmont, Shakespeare shifts the energy completely. While Venice screams, Belmont sparkles. Portia is living inside a romantic puzzle game and finally the contestant everyone has been waiting for arrives. Bassanio walks into her hall with the confidence of a man who has no idea how much debt is chasing him across the sea.

Portia sees him and instantly panics in the most charming way. She begs him not to choose the caskets too quickly because she knows she cannot help him and yet she desperately wants him to win. Shakespeare lets her speak from the heart.

“One half of me is yours and the other half yours.”

ABS translation,

I like you so much it is embarrassing me.

Now Bassanio begins the casket challenge. He looks at gold and rejects it because it is deceptive. Bassanio is flawed but he is not a fool. He looks at silver and rejects it because it represents vanity. He finally turns to the lead casket, dull on the outside, humble in appearance, and he recognizes the truth.

He chooses lead.

He opens it.

Portia’s portrait shines like destiny itself.

Belmont explodes with joy. Portia nearly collapses with relief. Shakespeare allows the only moment of pure happiness in the entire play. Bassanio wins the casket, wins Portia, wins the future. But Shakespeare never lets joy stay alone. He places tragedy right behind it.

Portia gives Bassanio a ring. She tells him the ring symbolises their bond. His heart, his loyalty, his identity. He must never remove it, never give it away.

“This house, these servants, and this same myself are yours.”

ABS translation,

I am giving you everything. Do not be stupid.

Bassanio promises. The audience knows he will absolutely be stupid.

Just then, like a curse timed perfectly, a messenger arrives from Venice. Antonio’s letter. A letter so tragic it drains all colour from the room. His ships are gone. His fortune is gone. He cannot repay the bond. Shylock demands the flesh. The date is fixed. Antonio is preparing for death.

Bassanio reads the letter aloud. His voice collapses.

Portia listens and realises instantly that the man she loves cannot enjoy their happiness if his friend is about to die because of him. She does not waste time with melodrama. She simply instructs Bassanio to go. She will handle Belmont. He must save Antonio.

Shakespeare now places his pieces for the final conflict.

Venice, the city of contracts, is ready.

Shylock, the man of wounds, is ready.

Antonio, the martyr without intention, is ready.

And Portia, the greatest strategist Shakespeare ever created, is preparing her disguise.

Act Three closes with money lost, love shaken, mercy tested, and a storm building toward a courtroom that will decide everything. ABS lights a candle and mutters,

Comedy has officially packed its bags.

ACT FOUR

Where The Court Becomes A Battlefield And Portia Becomes The Smartest Person In Europe

Act Four is the beating heart of The Merchant of Venice. Shakespeare throws every character into a courtroom and then lets intellect, vengeance, mercy, pride, and pure theatrical magic collide like a Renaissance Avengers finale. Venice gathers not for justice but for spectacle, and Shakespeare delivers with wicked pleasure.

We begin in the Venetian court where the Duke enters looking exhausted. He wants to persuade Shylock to show mercy. The Duke tries flattery, pity, and gentle manipulation. Shylock listens with the stillness of stone. He is done negotiating. Years of humiliation, insults, and mockery have hardened into a single demand.

“I will have my bond.”

ABS translation,

Stop giving speeches. I want the flesh you promised me.

Antonio arrives calm, almost saintlike, which is concerning because calm people in court are usually preparing to die. He tells the Duke he expects nothing better from Shylock and accepts his fate with a sigh that could extinguish every candle in the room. The Duke tries again to soften Shylock, but Shylock refuses with chilling logic. He tells them he hates Antonio. This is not business. It is personal.

Then Shakespeare delivers one of his coldest lines.

“If every ducat in six thousand ducats were in six parts and every part a ducat, I would not draw them. I would have my bond.”

ABS translation,

You could pay me a mountain of gold and I would still choose the pound of flesh.

Bassanio enters and falls apart emotionally, offering ten times the amount. Shylock refuses. Gratiano insults him. Shylock ignores him. Antonio quietly prepares for the end.

Just when the play seems doomed to bleed, the door opens and salvation enters wearing a disguise. Portia arrives, dressed as a young male lawyer, with Nerissa as her clerk. Shakespeare lets irony sparkle. Venice’s most serious legal problem is about to be solved by a woman who is not even supposed to be in the courtroom.

The Duke welcomes Portia believing she is a brilliant lawyer sent by Bellario of Padua. Portia plays the role so perfectly that even the scholars in the room bow to her brilliance. She examines the bond, studies the situation, and listens to both sides with the patience of a saint and the calculation of a chess grandmaster.

Portia’s first move is not legal but moral. She begs Shylock to show mercy. Then she delivers the speech that became immortal, the speech that has been quoted by judges, kings, professors, and pretentious dinner guests for centuries.

“The quality of mercy is not strained, it droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven.”

ABS translation,

Mercy makes you human. Try it once.

Shylock rejects mercy as if it were poison. He wants the law. He wants the bond. He wants the flesh. Portia nods gently, and in that nod the audience should hear a silent drum roll. She is about to rearrange the universe.

She tells Shylock he may indeed take a pound of flesh, exactly as the contract says. The court gasps. Antonio prepares for death. Shylock sharpens his metaphorical knife. Portia waits.

Then she strikes.

“This bond gives thee no jot of blood.”

The courtroom freezes. Shylock must take the flesh without shedding a single drop of blood. One drop equals murder. Murder equals execution. Portia has just turned the entire case inside out with one sentence.

ABS translation,

Congratulations, you trapped yourself.

Shylock collapses inside his own logic. He tries to escape. He begs to accept the money instead. Portia refuses. The tables have turned too perfectly. Venice watches the reversal with morbid delight.

But Shakespeare is not done. Portia reveals Shylock’s attempt to take a citizen’s life is punishable by law. Half his wealth goes to the state, half to Antonio. His life lies in the Duke’s mercy. Venice loves justice only when it hurts someone else.

The Duke spares Shylock. Antonio softens the punishment, but still demands he convert to Christianity and leave his wealth to Lorenzo and Jessica after his death. It is disguised as mercy, but it is also domination. Shakespeare lets the audience feel the weight of it. The room celebrates victory, but the cost is deeply unsettling.

Antonio is saved. Shylock is broken. Bassanio is relieved. Gratiano is loud as usual. Portia has single handedly saved the day and no one knows the truth.

The act ends with the courtroom emptying and Portia, still disguised, whispering to Nerissa that they are not done yet. The men think the story is over. Portia knows Venice is only half the battle. Belmont awaits, and so does a ring that Bassanio is absolutely going to mishandle.

ABS leans back and says,

The law survived. Logic triumphed. Humanity took a beating.

ACT FIVE

Where Belmont Becomes A Comedy Club And Venice Tries To Remember How To Smile

Act Five returns us to Belmont, the land of candlelight, music, and people who behave like they have never heard of stress. Shakespeare knows the audience has survived emotional war in Act Four, so now he gives everyone a soft landing, a playful ending, and enough banter to remind us that life moves on even after courtroom earthquakes.

We begin with Lorenzo and Jessica sitting under the moonlight, exchanging romantic lines with the kind of poetic confidence only eloping couples possess. They compare themselves to famous lovers from history and myth. Troilus and Cressida, Thisbe and Pyramus, Dido and Aeneas. Lorenzo quotes. Jessica teases. They pretend their story is just as tragic and romantic.

“In such a night as this.”

ABS translation,

Tonight is dreamy, let me flirt like I own the moon.

This scene is Shakespeare telling the audience to breathe. No trials, no knives, no contracts. Just young lovers showing off their memory of classical references. Shakespeare loves giving homework to the audience.

Suddenly, music floats in from Portia’s estate. Servants prepare for her arrival. Lorenzo and Jessica enjoy the peace, unaware that chaos, disguised in the form of rings and wounded male egos, is galloping toward them.

Now Portia and Nerissa enter, tired from their secret lawyer missions but glowing with the satisfaction of having outsmarted an entire city. Portia asks her household not to reveal that she and Nerissa have returned earlier than expected. She is planning a surprise inspection of Belmont.

And right on cue, Bassanio arrives with Antonio in tow. Poor Antonio is dragged around like the emotional support gentleman of Venice. Bassanio is happy to see Portia but nervous because he knows he lost the ring. Gratiano appears and also looks guilty because he lost his ring too. Absurdly, Gratiano blames everything on the judge’s clerk, who of course was Nerissa in disguise.

Portia begins her performance with the calm rage of a woman who knows she is absolutely right. She asks Bassanio for the ring she gave him. Bassanio panics like a rabbit caught by destiny. He stammers. He tries to explain. He tries charm. Portia stays stone cold.

“You gave away my ring.”

ABS translation,

Explain yourself, darling, but I am not saving you.

Bassanio swears that he only gave it away under noble circumstances. Portia pretends to be offended that he valued another person’s request more than her love. She frames it as betrayal, dignity, loyalty, and honor. Bassanio melts into apology mode while Antonio watches, traumatised by yet another emotional crisis that is not his fault.

Then Nerissa attacks Gratiano with the same accusations, and suddenly Belmont becomes a full comedy show. Two men explaining. Two women interrogating. Antonio suffering silently. The servants blinking like confused owls.

Shakespeare is having fun. He wants us to see the ridiculousness of men who promise eternal devotion but cannot hold onto one simple ring.

Portia finally ends the drama by revealing the truth. She and Nerissa were the lawyer and clerk. They were the ones who solved the court case. They were the ones who took the rings. Bassanio and Gratiano collapse into confused gratitude.

Antonio stands quietly until Portia hands him a letter. It is from Venice. The news is miraculous. Some of Antonio’s ships have survived after all. His fortune is not completely destroyed. Shakespeare never lets tragedy win entirely.

“Sweet lady, you have given me life and living.”

ABS translation,

Thank you for saving my body, my bank account, and my dignity.

Portia then hands everyone the gifts they need. She gives Antonio the good news. She gives Bassanio forgiveness. She gives Gratiano a good scolding. She gives Lorenzo and Jessica a deed granting them Shylock’s inheritance in the future. She gives Nerissa a final laugh.

Shakespeare wraps everything in harmony.

The lovers are reunited.

Antonio is safe.

Belmont glows again.

Mercy softens the sharpness of the past.

Comedy takes back the stage.

Yet Shakespeare’s ending is not syrupy. He hints at wounds that will not fully heal. Shylock disappears from the story. Jessica is joyful but haunted. Antonio, though financially saved, remains emotionally fragile.

But in Belmont, under moonlight, life chooses laughter over bitterness.

The act closes with music, witty lines, soft teasing, and the final note that Belmont, not Venice, has the authority to close this story.

ABS closes the scroll with a smirk and says,

Nothing ends perfectly, but it ends well enough for Shakespeare to dismiss the audience with a satisfied bow.

A Comedy That Smiles With One Side Of Its Face And Bleeds With The Other

The Merchant of Venice pretends to be a comedy, but Shakespeare never lets the audience get too comfortable. He hands you laughter in Belmont and then quietly slips a knife between the ribs in Venice. It is a play built on contradictions. Love and money. Mercy and revenge. Wit and wounds. It moves like a seesaw between beauty and brutality, and Shakespeare enjoys watching the audience lose balance.

The play gives us Portia, one of the sharpest intellects in English drama, solving a legal crisis that leaves Venice speechless. And it gives us Shylock, a man shaped by cruelty, whose pursuit of justice turns into the world’s most famous moral disaster. Shakespeare refuses to make it simple. No one walks out of this play fully innocent. No one walks out untouched.

Belmont sparkles, but Venice burns beneath it.

Portia wins, but Shylock breaks.

Antonio survives, but he does not heal.

Jessica escapes, but she loses more than she knows.

This is Shakespeare at his most dangerous. He gives you a happy ending, but he fills the margins with uncomfortable truths. He tells you that mercy is divine, but he shows you how merciless humans can be. He closes the play with music and moonlight, but the silence underneath is heavy.

And that is why the play endures.

Not because it is a neat comedy.

But because it is a messy, brilliant argument about what justice costs, what love risks, and what people will do when pushed against the limits of their world.

It laughs. It hurts. It sings. It questions.

It leaves you smiling and unsettled at the same time.

Which is exactly how Shakespeare wanted it.

ABS folds the scroll, thinking about how Venice never settles its debts, Belmont never loses its perfumes, and Shakespeare never lets anyone leave the stage without one last sting of truth

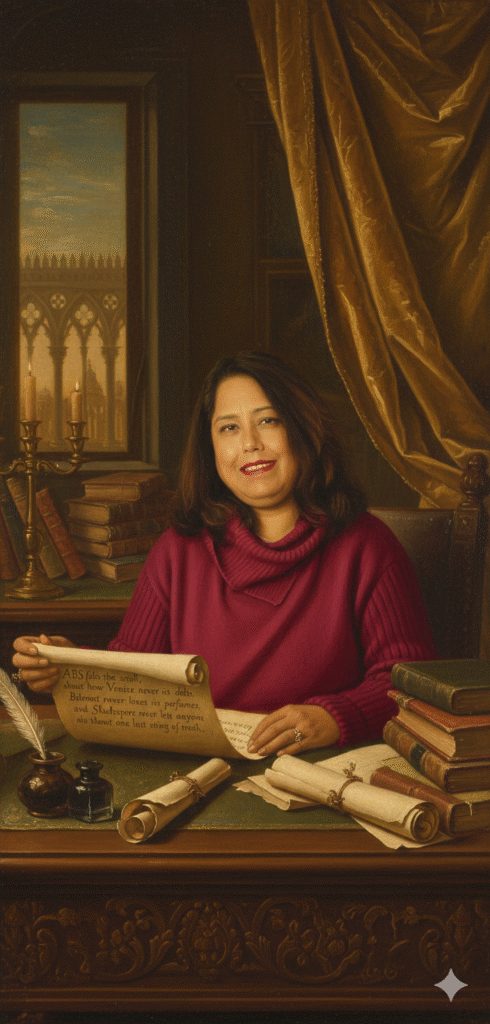

Abha Bhardwaj Sharma is a Professor of English Literature with over 25 years of teaching experience. She is the founder of Miracle English Language and Literature Institute and the author of more than 50 books on literature, language, and self-development. Through The Literary Scholar, she shares insightful, witty, and deeply reflective explorations of world literature.

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance