From Silent Observer to Meaning-Maker—The Rise of the Reader in Literary Theory

From The Professor's Desk

When the Reader Walked In: The Rise of Reader-Response Theory

For centuries, literature was a monologue—written by the author, decoded by the critic, and quietly admired by the reader. The text was sacred, the author was sovereign, and the reader… well, the reader was merely present. Until something radical happened:

the reader walked in—not as a guest, but as a co-creator.

Reader-Response Theory is the story of this entrance. It marks one of the most profound shifts in literary theory—a move from asking what does the text mean? to what happens when someone reads it? From fixed meanings to fluid interactions. From texts as closed systems to reading as an open-ended process.

This transformation didn’t occur in isolation. It was a quiet revolt against the dominance of New Criticism, which trained readers to focus solely on the text—its irony, structure, and unity—while dismissing authorial intention and reader reaction as “fallacies.” But what Reader-Response theorists saw was not a fallacy, but fertile ground. They realized that meaning does not exist prior to reading—it is born in the act itself.

It was Stanley Fish who boldly declared that meaning is not a matter of discovering what the text says, but of recognizing how readers are shaped by communities of interpretation. It was Wolfgang Iser who asked us to consider the implied reader—the invisible figure for whom the text seems to prepare a path. It was Louise Rosenblatt who told us reading is not passive reception, but a transaction—a kind of dialogue between the page and the person.

“The text activates a repertoire of expectations in the reader—what matters is not just what the text says, but what it asks us to do with it.”

— Wolfgang Iser

With this, the curtain lifted. The reader was no longer a bystander.

The reader had become the stage.

1. The Reader Emerges: Background and Evolution

There was a time when the literary text was a sealed box, and the critic’s job was to pick the lock. Meaning was something hidden inside—a puzzle with one elegant solution, discoverable only through trained neutrality. The New Critics had drawn the lines of this intellectual battlefield: banish the author, ignore the reader, and treat the text as a self-contained organism of irony, structure, and paradox. Literature, they believed, explained itself.

But as the 20th century unfurled—with its wars, exiles, and revolutions—such neatness began to look suspicious. Was the text really so stable? Was meaning so immune to the one thing literature had always depended on—the reader?

The emergence of Reader-Response Theory was not a sudden upheaval but a slow philosophical shift. It was the story of meaning not as possession, but as encounter. Of the reader not as spectator, but as participant.

Against the Text-as-Object: The Reaction to Formalism

New Criticism and its structuralist cousins had insisted on objective interpretation. Texts, in their model, were autonomous verbal artefacts, best understood through “close reading” that bracketed out intention, emotion, and audience. The author was declared dead—but so was the reader, quietly buried beneath textual symmetry.

Reader-response theory arose as a resistance to this closure. Its first instinct was to break open the sealed box—not to vandalize the text, but to observe what happened when someone opened it. Reading, it argued, is not a passive act of decoding—it is a performance, an event, a negotiation between expectation and surprise.

“A poem is not its words, it is the performance those words elicit.”

— Stanley Fish

This was not mere sentiment. It was a philosophical reorientation with deep roots in European thought.

Phenomenology and Hermeneutics: The Roots Beneath the Reader

The conceptual groundwork for reader-response theory was laid by the phenomenologists—those who insisted that experience is not a mirror but a lens. Thinkers like Edmund Husserl and Roman Ingarden argued that perception is not passive reception, but intentional consciousness—a process of shaping, selecting, and interpreting what is given.

Roman Ingarden, in particular, offered a literary application of Husserlian ideas. In his The Literary Work of Art, he distinguished between the text (a fixed structure of signs) and its realization (the dynamic process that happens when a reader activates that structure in their own mind). According to Ingarden, the literary work does not exist fully until it is read. Meaning, therefore, is not transmitted—it is performed.

This idea would later echo in the theories of Wolfgang Iser, Stanley Fish, and others—but it was Hans-Georg Gadamer who provided the critical hermeneutic bridge. In Truth and Method, Gadamer argued that understanding is not the reconstruction of original intent, but a fusion of horizons—the meeting of the reader’s world with the world of the text. The reader brings questions, assumptions, and historical perspective—and these shape the meaning that emerges.

“Every reading is a re-writing. And every understanding is an act of translation.”

— Paraphrased from Gadamer

This was a radical invitation. The reader was no longer at the mercy of the text. The reader was now the terrain across which meaning would walk.

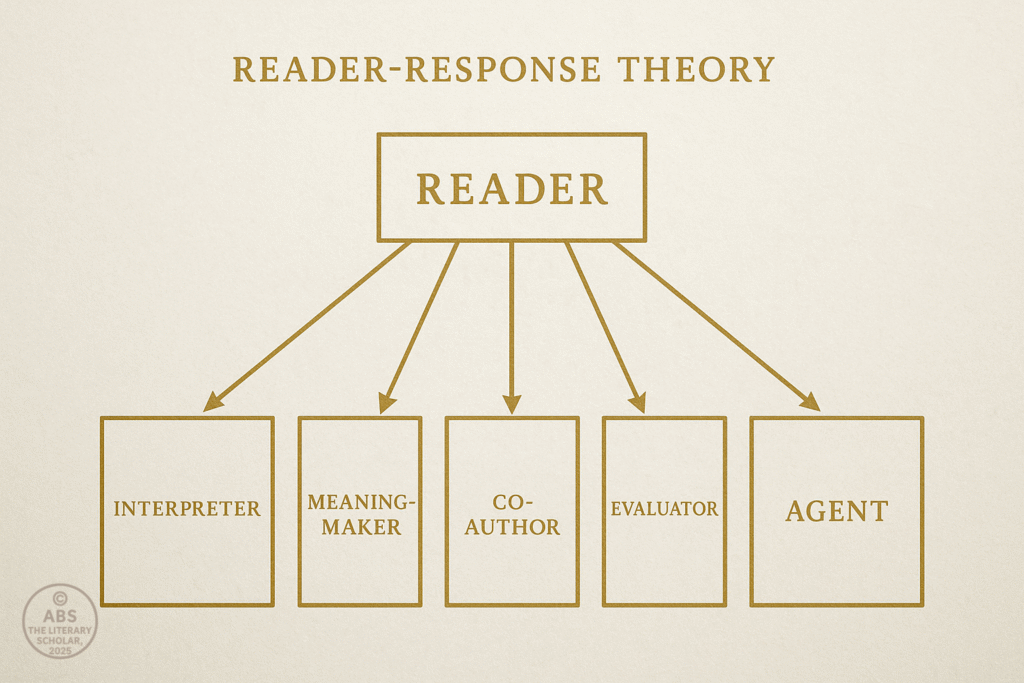

The Reader as Dynamic Agent

By the time Reader-Response Theory entered Anglo-American critical discourse in the 1960s and 70s, it came with philosophical teeth. The reader was not merely sentimentalized—it was theorized.

Meaning, as reader-response scholars began to argue, is not in the text; it happens between the reader and the text. It is an event, not a property. A novel is not simply understood—it is completed in the mind of the reader.

This realization splintered the old assumptions about literary value, objectivity, and the role of interpretation. If meaning varied from reader to reader, was anything fixed? If interpretation depended on the reader’s background, mood, and cultural position, could criticism ever be universal?

The answer, from theorists like Wolfgang Iser, was cautious but clear: the reader matters—but not all readings are equal. There is an implied reader—a model reader the text seems to imagine and construct as it unfolds. And the text itself provides gaps—spaces of indeterminacy that the reader must fill. Reading is, then, an active process of collaboration, not of chaos.

Meanwhile, Stanley Fish went even further. He argued that all readings are shaped by interpretive communities—shared ways of seeing, institutionalized habits of thought, cultural filters. You read as who you are, but who you are is also shaped by the communities that trained your vision.

This idea opened a floodgate. It meant that literature could no longer be studied as if readers were neutral instruments. Every reading was situated, ideological, and inescapably human.

Toward an Open-Ended Text

Reader-response theory does not claim that the text disappears. What it claims is that meaning cannot pre-exist the encounter. The text offers possibilities, but the reader chooses the path. The same novel read in adolescence, in grief, in exile, or in retrospect—each time yields a different meaning, not because the words changed, but because you did.

This theory would find application not only in classrooms and critical circles, but in everything from marketing to social media to fan fiction communities. It is no accident that in an age of interactivity, reader-response has become more relevant than ever. Every online review, meme annotation, or YouTube book essay is a reader-response in motion.

But it all began with a question that once seemed naïve:

What happens when someone reads a book?

And the answer turned out to be:

The book begins.

2. Fish, Iser, and the Reader in the Text

There comes a moment in every reader’s life—mid-novel, mid-sonnet, mid-stumble over some elliptical line—when they realize: the book is watching them just as much as they are reading it. The idea that literature is a two-way act—that a text is only half-complete until a reader brings it to life—is at the heart of Reader-Response Theory. But two thinkers brought this insight into sharp academic focus: Stanley Fish and Wolfgang Iser. Their frameworks would redefine how we think of texts—not as fixed objects, but as arenas of interaction.

Their theories—though seemingly opposed—are best read not as a duel, but as a dialectic: Fish and Iser gave us the two poles between which most serious Reader-Response criticism swings—subjective variability and structured collaboration.

“Interpreters do not decode poems; they make them.”

— Stanley Fish

Stanley Fish and the Community of Meaning

Stanley Fish is perhaps the most provocative of the reader-response thinkers. In his radical formulation, there is no meaning without a reader—and no reader without a community. In his 1980 essay collection Is There a Text in This Class?, Fish proposed the idea of “interpretive communities”: the notion that what we understand from a text is shaped not solely by individual subjectivity, but by the cultural-linguistic frameworks in which we’ve been trained.

Fish challenges the idea of a text as an objective object waiting to be interpreted correctly. Instead, he claims that texts don’t have meaning in themselves; meaning is what interpretive communities allow us to see.

This is not pure relativism. Fish isn’t saying “anything goes.” He’s saying that when you read, you’re never truly alone. You’re drawing on expectations, codes, assumptions, and institutionalized habits of thought that shape how you perceive, what you value, and which patterns you notice.

“Interpretive strategies are not put into practice after reading; they are the shape of reading.”

— Stanley Fish

Thus, a romantic poem read by a 19th-century transcendentalist will mean something profoundly different from how it is read by a postcolonial scholar—or a teenage reader on Instagram. Not because the poem changed, but because its frame of reference did.

Fish’s view was groundbreaking because it removed even the illusion of neutrality. The reader was no longer innocent. The reader came with baggage—and that baggage shaped the journey.

But if Fish painted reading as culturally pre-shaped, Wolfgang Iser offered a different kind of structure: one built into the text itself.

Wolfgang Iser and the “Implied Reader”

Wolfgang Iser, associated with the Constance School of Reception Theory in Germany, believed that texts were not passive victims of interpretation, but strategically incomplete structures—invitations to collaboration. His key concepts are the “implied reader” and “gaps” (or Leerstellen in German), which allow literature to remain open without becoming unmoored.

The implied reader is not a real person—it’s the reader that the text seems to expect, anticipate, and guide. This reader is built into the structure of the narrative through tone, genre, style, cultural references, and narrative cues. When we read, we step into that role—even if we don’t always fit it perfectly.

The “gaps” in a literary text are places of indeterminacy—moments the author leaves unresolved, ambiguous, or open to interpretation. The reader fills these gaps based on their own experience, background, and sensitivity. But not randomly. The text frames the range of possible completions, and this is where Iser maintains the idea of structured variability.

“Reading is a process of continual modification of expectations.”

— Wolfgang Iser

In contrast to Fish’s more fluid model, Iser sees reading as a dynamic oscillation between the text and the reader. Each reading is a negotiation between what is present and what is absent, what is said and what is suggested.

The act of reading becomes a loop—anticipation, retrospection, revision. The reader constantly adjusts understanding as more information comes in, modifying earlier assumptions, reframing characters, re-evaluating motives. Literature, in this sense, exists in time, unfolding through reader interaction.

Iser’s model allows for subjectivity without falling into chaos. The reader brings variation, but the text provides architecture.

Subjectivity vs Normativity: Where Is the Line?

One of the major criticisms of reader-response theory is that it could open the door to subjective chaos—the idea that any interpretation is valid, and therefore none are falsifiable. If the reader co-creates the meaning, what keeps us from reading Pride and Prejudice as a spy thriller or Hamlet as a romantic comedy?

Fish’s answer: community standards. You are trained, whether you know it or not, in what counts as “reasonable” or “probable” within your interpretive world. Interpretations are not purely idiosyncratic—they are culturally sanctioned acts of recognition.

Iser’s answer: the text’s design. While gaps exist, not every gap can be filled any way you like. A coherent reading must be textually justifiable, even if it’s personally variable.

Thus, reader-response theory is not relativism. It is structured subjectivity. There are limits—not imposed from above, but shaped by discourse, history, and textual mechanics.

“The reader brings the text to life, but the text whispers what kind of life it can live.”

The Reader as Co-Author

Both Fish and Iser agree on one powerful idea: the reader is not a parasite on the text—they are its midwife. Without the reader, the text remains inert, unrealized. The reader is not merely decoding something hidden, but constructing meaning in a partnership that is always shifting, culturally embedded, and historically situated.

Yet this raises the final philosophical tension: Who is the reader, really?

Is the reader an individual, a singular self with unique feelings and thoughts, responding freely and emotionally? Or is the reader always already a product of cultural training, gender, class, race, education, ideology?

Fish leans toward the second: the reader is made by discourse.

Iser allows more room for play: the reader is both agent and structure, a self in motion across a text that guides and disrupts in turn.

Both views are essential to the modern understanding of literature. They remind us that reading is never innocent, and yet it is always intimate.

“Texts are not containers of meaning. They are invitations to meaning-making.”

Section 3: “Mind, Mood, and Meaning: Psychological and Transactional Approaches”

If Stanley Fish made the reader visible and Wolfgang Iser gave that reader a role, then scholars like Norman Holland, David Bleich, and Louise Rosenblatt turned the lens inward—into the reader’s mind, emotions, history, and mood. In their hands, Reader-Response Theory became not just a method of interpretation but a psychological, even therapeutic, exploration of what it means to read.

Norman Holland: The Reader as Identity in Motion

Norman Holland’s contributions to Reader-Response Theory are inseparable from his psychoanalytic training. For him, every act of reading is an act of self-reconstruction. The text, in his view, does not simply exist to be decoded—it is a mirror, a playground, a site for the enactment of individual psychological needs and defenses.

“We don’t just interpret texts. We interpret ourselves through them.”

— Norman Holland

Holland developed what he called the identity theme—a unique internal pattern that shapes how each reader engages with literature. His claim was bold: we read texts not for what they say, but for how they let us be ourselves in safe, symbolic ways. A gothic novel may satisfy an unconscious fear. A romantic poem may activate longings shaped in childhood. For Holland, no reading is universal because no reader is.

David Bleich: Meaning is What Readers Make Together

If Holland turned interpretation into therapy, David Bleich turned it into collective subjectivity. He rejected the idea that meaning lies anywhere in the text. Instead, he emphasized interpretive communities in action, especially within the classroom. His method was revolutionary: students wrote down their personal, emotional, or associative responses before any discussion of plot or theme.

“Meaning is not something to be found but something to be made.”

— David Bleich

Here, meaning becomes a social construct. It is not what the author intended or even what the words dictate. It is how readers respond in conversation, building knowledge not from authority but from experience. This approach proved powerful in feminist, multicultural, and postcolonial classrooms, where marginalized voices could reclaim texts through their own lived contexts.

Louise Rosenblatt: Reading as Transaction

While Bleich and Holland leaned heavily on psychology and subjectivity, Louise Rosenblatt brought balance with her theory of the transactional relationship between reader and text. In her landmark book Literature as Exploration, she argued that neither the reader nor the text alone creates meaning—it is the encounter that matters.

“The reading of any work of literature is, of necessity, an individual and unique occurrence involving the mind and emotions of a particular reader.”

— Louise Rosenblatt

Her theory laid the groundwork for Reader-Response pedagogy—reading as a dynamic interaction, with the text offering a structured possibility, and the reader bringing their own identity, context, and affect. Unlike Holland, Rosenblatt did not believe anything goes. She emphasized evidence from the text, clarity of argument, and shared reasoning, making her theory one of the most pedagogically robust.

The Classroom as a Critical Site

Reader-Response Theory flourished in the classroom because it validated the student. Rather than being told what a poem means, students could be invited to explore what it does to them, and then defend, articulate, and refine that experience. This shift turned passive learning into interpretive inquiry, allowing for student empowerment, cultural dialogue, and critical literacy.

Feminist and postcolonial educators embraced this method. A traditional reading of The Tempest, for instance, could be disrupted when students from colonized nations responded to Caliban’s pain rather than Prospero’s power. In a feminist setting, the reading of Jane Eyre might pivot to Bertha Mason’s silence instead of Rochester’s passion. These shifts were not distortions—they were acts of critical realignment made possible by Reader-Response’s openness to plurality.

A Beautiful Chaos or a Slippery Slope?

But not all was applause. Reader-Response Theory, especially in its subjective extremes, drew criticism for enabling relativism. If any response is valid, how do we teach interpretation, assess understanding, or discuss literature meaningfully?

Stanley Fish countered this with his concept of interpretive communities, arguing that no reader reads alone—we are shaped by institutions, cultures, and discourses that give shape to our reactions. Yet, the tension persists: is meaning discovered, constructed, or both?

This question remains at the heart of literary theory today.

Section 4: “From Theory to Practice: Reader-Response in Criticism and Culture”

If literature is not a transmission but a transaction, then its afterlife lies not in footnotes—but in fans, forums, and feedback. The theory of Reader-Response, once nestled in seminars and scholarly monographs, has quietly slipped into the bloodstream of contemporary reading culture. Now, every dog-eared copy, every marginal note, every Goodreads rant is part of a wider literary act—where the reader is no longer silent, but central.

Application in Literary Criticism and Teaching

Reader-Response Theory revolutionized how literature is taught. No longer did classrooms demand the ‘correct’ reading—as ordained by the teacher or the ‘authorial intention’. Instead, Louise Rosenblatt’s transactional theory transformed pedagogy: meaning wasn’t waiting inside the text like a raisin in a bun. Meaning was what happened between reader and text in a specific moment of encounter.

“The poem, then, must be seen as an event in time. It is not an object or a thing.” — Louise Rosenblatt

Teachers began encouraging reflective journals, dialogic readings, and collaborative interpretations. Students were no longer vessels but co-pilots in textual exploration. Even the examiners grudgingly accepted that more than one answer could be right—provided it was well-argued, well-grounded, and rooted in textual response.

Interpretation as Extension: From Diaries to Fan Fiction

Reader-Response doesn’t end with interpretation; it mutates into creation. The personal diary that records one’s emotional reaction to Jane Eyre is one form. But the online fan fiction that rewrites Mr. Rochester as a bisexual vampire-hunter in a dystopian Toronto? That too is Reader-Response—just with more eyeliner and lasers.

When readers rewrite endings, imagine prequels, or ship unlikely couples (Wuthering Heights meets Bridgerton, anyone?), they are asserting interpretive ownership. This is not blasphemy; it is literary democracy. It proves Fish’s point: texts don’t dictate—they invite.

“Interpretation is not the art of construing but the art of constructing. Interpreters do not decode poems; they make them.” — Stanley Fish

Reader-Response in the Digital Age

Enter the digital agora: online reading groups, fan communities, book vlogs, TikTok literary rants, and Goodreads reviews with reactions like “I threw this book across the room at page 47 and I regret nothing.”

Each of these is Reader-Response Theory in action. Unruly, unfiltered, and deeply subjective—but also sincere, passionate, and often rooted in real affective labor.

Instagram pages annotate Emily Dickinson with Gen Z sarcasm. Reddit threads deconstruct Shakespeare’s sonnets with queer theory and memes. These are not devaluations of literature; they are its evolution. Reader-Response has democratized criticism, dethroned the ivory tower, and handed the mic to the reader in the cheap seats.

In fact, even algorithms now participate. Streaming services and eBook platforms track our pauses, rereads, and highlights. Your Kindle knows which passages make your heart skip. In a posthuman sense, even machines are becoming interpretive communities.

Back to Fish: No Interpretation Is Innocent

As Reader-Response exploded across platforms, some critics warned: Is everything a valid reading? Is there no anchor, no common ground?

Stanley Fish anticipated this. His theory of interpretive communities reminds us that our readings are not free-floating. They are shaped—often unconsciously—by our social, academic, and ideological environments. You don’t interpret The Great Gatsby the same way in an MBA program and a queer literature class. That doesn’t mean one is false. It means each reading is contextually true.

“All objects are made and not found, and made by the interpretive strategies we set in motion.” — Stanley Fish

Reader-Response is not chaos. It is coherence negotiated anew each time. Literature becomes less about ‘what it is’ and more about ‘what it does’—to us, in us, and through us.

The age of the solitary, all-powerful author is over. In its place stands a more collaborative figure: the reader. No longer a mute observer or passive receiver, the reader is now a lens, a voice, and—most strikingly—a question. Every reading becomes a negotiation, a reflection, a dialogue between what is on the page and what is already pulsing within the reader’s mind and memory.

As Stanley Fish famously said, “Interpretation is not the art of construing but the art of constructing. Interpreters do not decode poems; they make them.” And with that, literature is no longer a fixed object—it is a process in motion.

From Rosenblatt’s gentle insistence that “the poem happens during the transaction between reader and text” to Wolfgang Iser’s belief that the “implied reader” is built into the structure of the text itself, we are reminded that every book is unfinished until someone turns its pages with intent. Meaning, then, is not contained—it is activated.

But this activation is not wild chaos. Reader-response theory does not give license to say anything means everything. Rather, it urges us to acknowledge that meaning is shaped—not just by the words written, but by the lives reading them.

Somewhere, in a quiet library, a student reads a well-worn copy of Jane Eyre. Her experiences, fears, hopes—all begin to stir within the sentences. She does not just understand the text. She becomes its co-author.

ABS, The Literary Professor

leans back in reflection, watching as the silence of reading echoes with new meaning. The text breathes again—because someone read it.

ABS folds the annotated text gently, placing it beside a reader’s open journal—where the margin notes speak as loudly as the lines.

Signed,

ABS

The Literary Professor

www.theliteraryscholar.com

Scroll Index: Explore Literary Theory Explained

(Click any to begin)

Share this post / Spread the witty word / Let the echo wander / Bookmark the brilliance